Exposing Vulnerabilities: Physical Adversarial Attacks on AI-Based Fault Diagnosis Models in Industrial Air-Cooling Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work and Contribution

2.1. Attacks on Machinery and Vibration Fault Diagnosis

2.2. Attacks on Industrial Soft Sensors and CPS

2.3. Methodologies, Benchmarks, and Defense Strategies

2.4. Comparison with Recent Approaches

2.5. Contribution

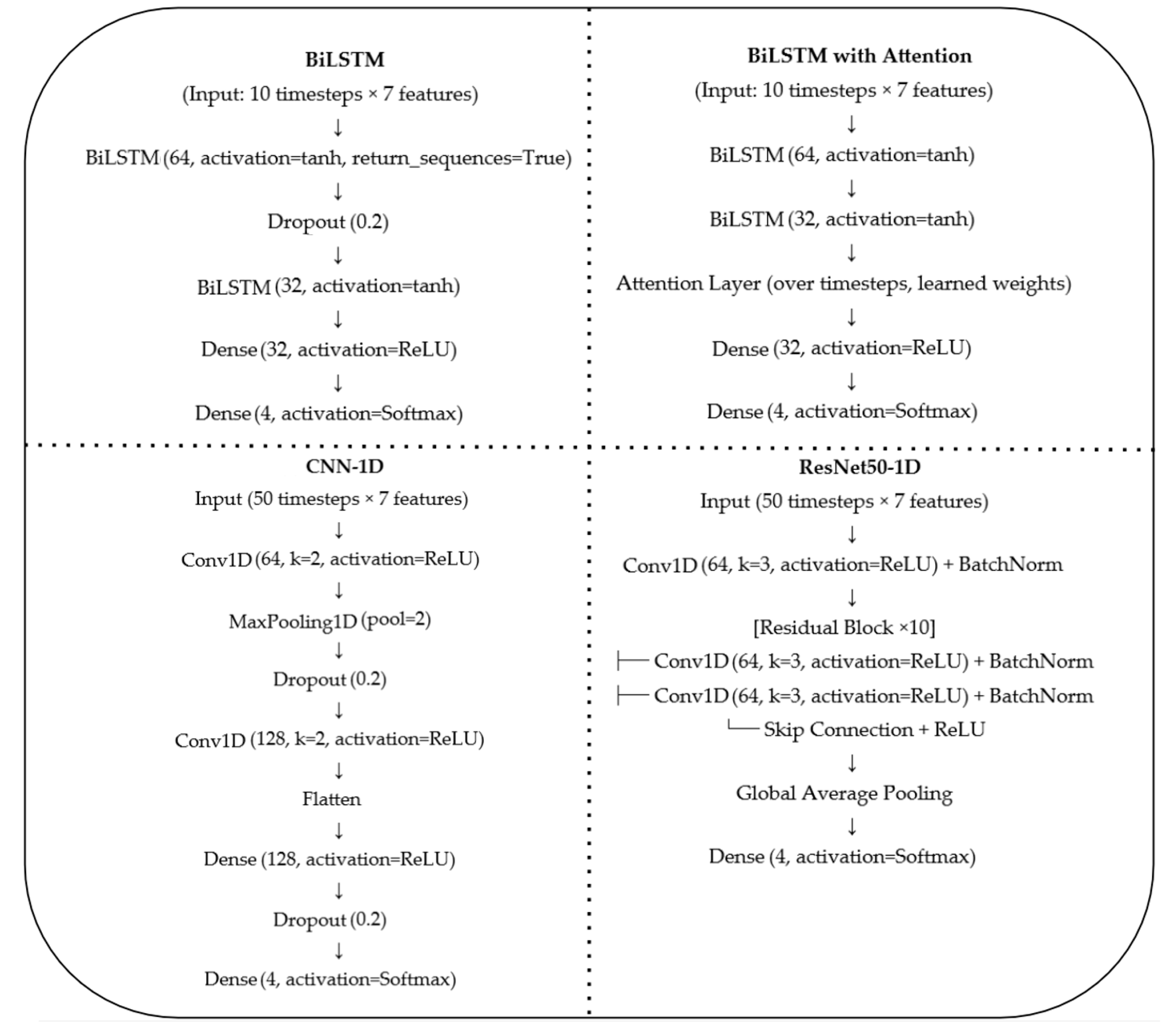

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Proposed Methodology

- RQ1: How do real-world physical disturbances affect the reliability of AI-based fault diagnosis systems in industrial environments? This question seeks to empirically evaluate how subtle physical interventions (e.g., sensor misalignment, mechanical imbalance) affect the predictive behavior and classification confidence of deep learning models under real production conditions.

- RQ2: What defense strategy can enhance the resilience of such systems against adversarial conditions? This question examines the effectiveness of modular, transfer-learning-based defense mechanisms in mitigating adversarial confusion and whether such architectures can maintain high diagnostic integrity under tampered scenarios.

3.2. Experimental Setup

3.3. Physical Attacks’ Data Capturing

- Misaligned Sensor: The vibration sensor was deliberately repositioned away from its optimal mounting location. Specifically, the sensor was detached and reattached with a lateral offset of approximately 5 mm and a rotational misalignment of ~15° relative to its original axis, in order to introduce distortions in the captured signals (Figure 4a).

- Loose Motor Foot: One of the mounting bolts of the motor base was deliberately loosened. The bolt was unscrewed with a controlled torque to induce partial destabilization without complete detachment (Figure 4b).

- Eccentric Shaft: The shaft had sustained wear from a previously installed bearing inner ring. The old bearing had left a circumferential groove (shoulder/pit) on the shaft surface. A new bearing was subsequently mounted without restoring the original shaft geometry, resulting in an improper and eccentric fit. This led to non-uniform support and slight misalignment between the shaft and bearing axis, producing asymmetric vibration patterns during operation (Figure 4c).

- Loose Bearing Cap: The bolts securing the bearing housing were partially unscrewed from their fully tightened position. This action reduced the preload on the bearing cover, causing minor mechanical instability without complete disassembly (Figure 4d).

- Impeller Add Weight: A small neodymium magnet was securely attached to the impeller at a location approximately 3 cm from the base of the blade. This eccentric mass placement introduced a controlled imbalance in the rotating system, altering its inertia and causing increased centrifugal loading. The modification was performed carefully to avoid mechanical damage, aiming to produce a detectable shift in the vibration profile. (Figure 4e).

- Acceleration Root Mean Square (aRMS): Quantifies the overall vibration energy by averaging the squared acceleration values over time. It reflects the intensity of oscillatory motion in terms of acceleration. High aRMS indicates persistent mechanical stress, typically due to imbalance, misalignment, or progressive wear. It is sensitive to sustained abnormalities, rather than transient events.

- Acceleration Peak (aPeak): Measures the maximum instantaneous acceleration within a given time window. It captures the strongest single vibration spike. High aPeak suggests the presence of sudden mechanical shocks, impacts, or momentary looseness, and it is highly sensitive to intermittent events that do not last long enough to significantly raise aRMS.

- Velocity Root Mean Square (vRMS): Calculates the RMS of vibration velocity, a quantity that reflects how fast oscillatory motion occurs over time. It is especially relevant in the mid-frequency range of rotating machinery. It is a strong indicator of mechanical resonance, imbalance, and structural fatigue. It is often used to assess long-term degradation or imbalance conditions.

- Crest Factor: Crest Factor is the ratio of the peak acceleration to the RMS acceleration, representing the impulsiveness or spikiness of the vibration signal. High CF indicates sharp, transient disturbances, while low CF indicates smooth, consistent vibration, possibly due to steady-state imbalance.

- Motor Speed (rpm) is included as a core input feature, since vibration response is inherently speed-dependent, providing any ML or DL model with RPM information enables it to learn fault-specific patterns across varying operating conditions, improving both accuracy and robustness in a real production environment. If the model does not “know” the motor speed, it cannot relate observed vibration frequencies to expected fault patterns under varying loads.

- Motor Temperature (°C) was included as a contextual feature to enrich the diagnostic capability of the model used. Although not a direct fault indicator in most cases, temperature provides valuable insight into thermal stress, load conditions, and the progression of mechanical wear. Its inclusion helps the model differentiate between vibration anomalies caused by faults and those driven by thermal operating conditions.

- Motor Current (Amps) was included as a final complementary feature reflecting the electromechanical interaction within the system. Mechanical faults such as imbalance, shaft misalignment, or bearing degradation often lead to increased or unstable current draw. Including current as a feature enables early detection of faults that impact torque or load characteristics and improves fault separability in conjunction with vibration-based features.

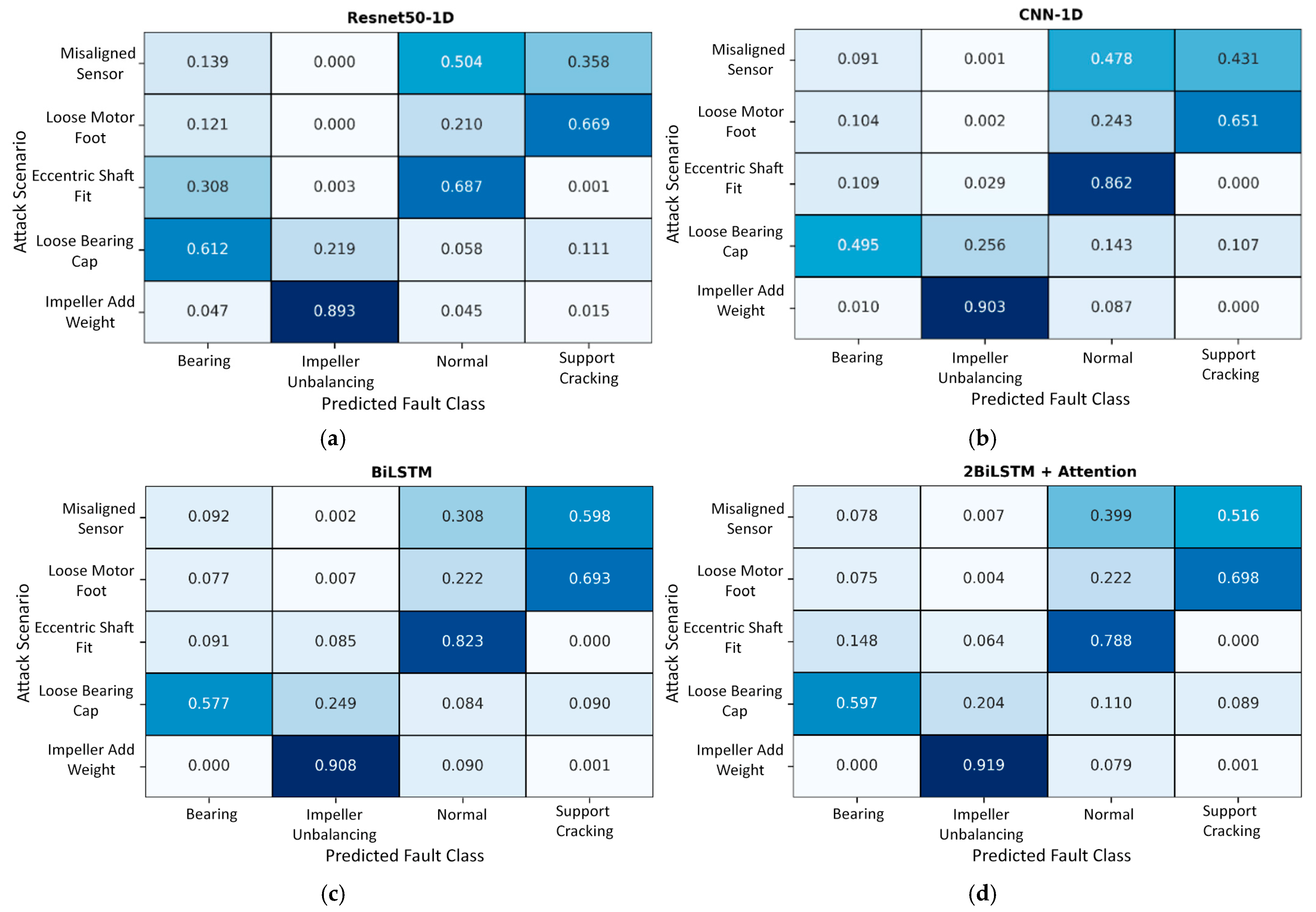

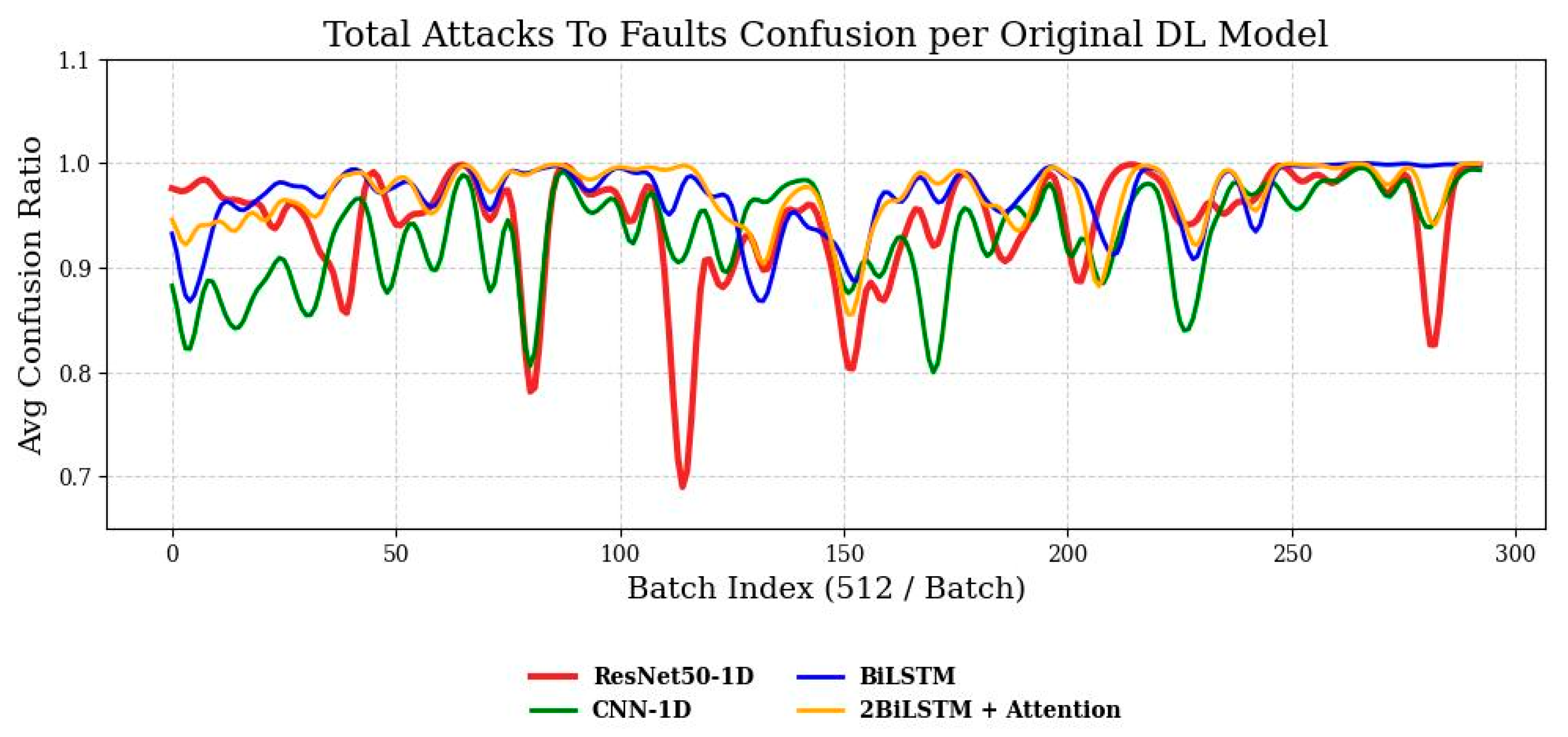

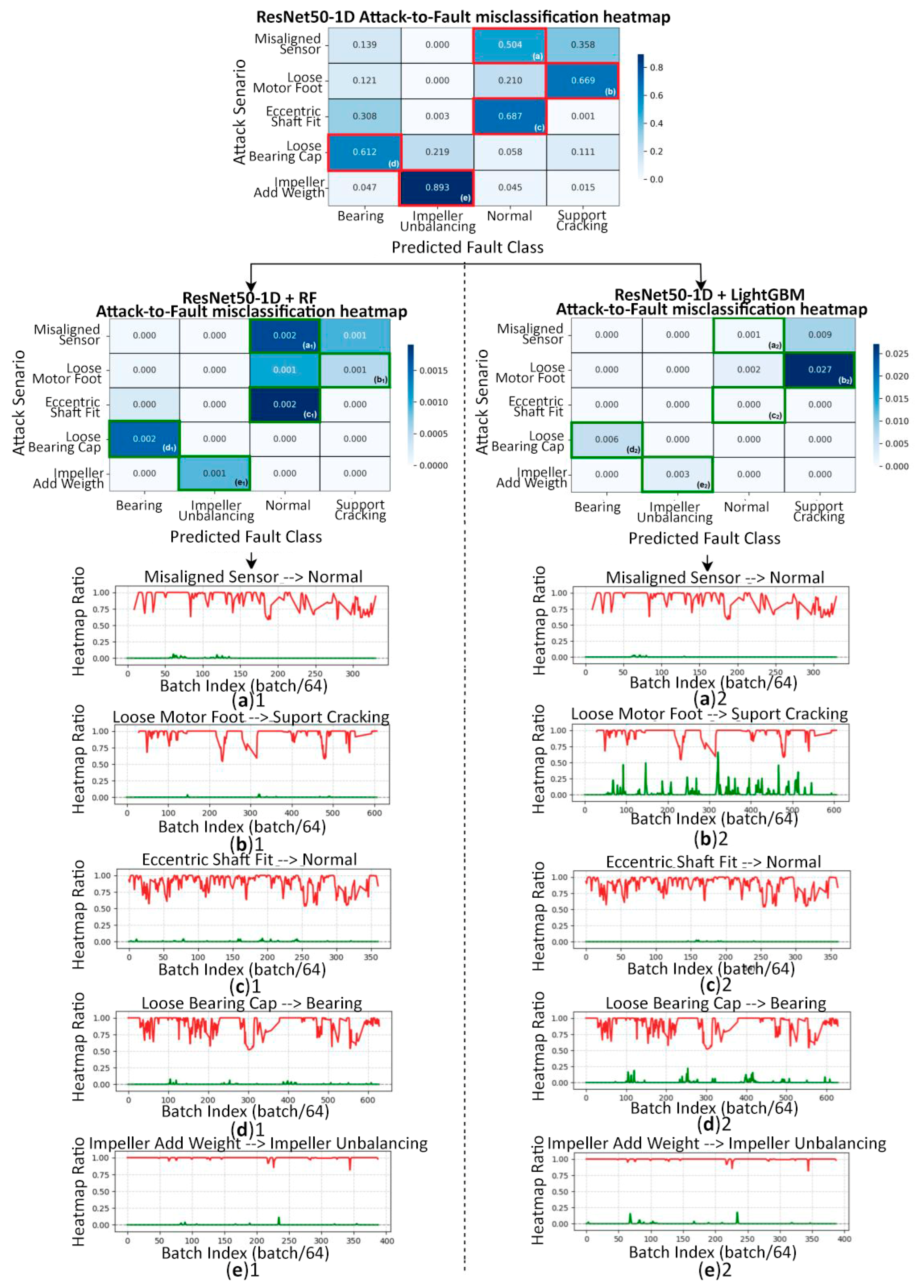

4. Robustness Testing Under Physical Attacks

- n = total number of attack scenarios;

- i = index of the attack scenario (row of the confusion heatmap);

- j = index of the predicted fault class (column of the confusion heatmap);

- Cij = normalized proportion of predictions where attack scenario i is classified as fault class j;

- maxj Cij = the maximum misclassification confidence for attack i, i.e., the fault class in which the model most strongly confuses that attack.

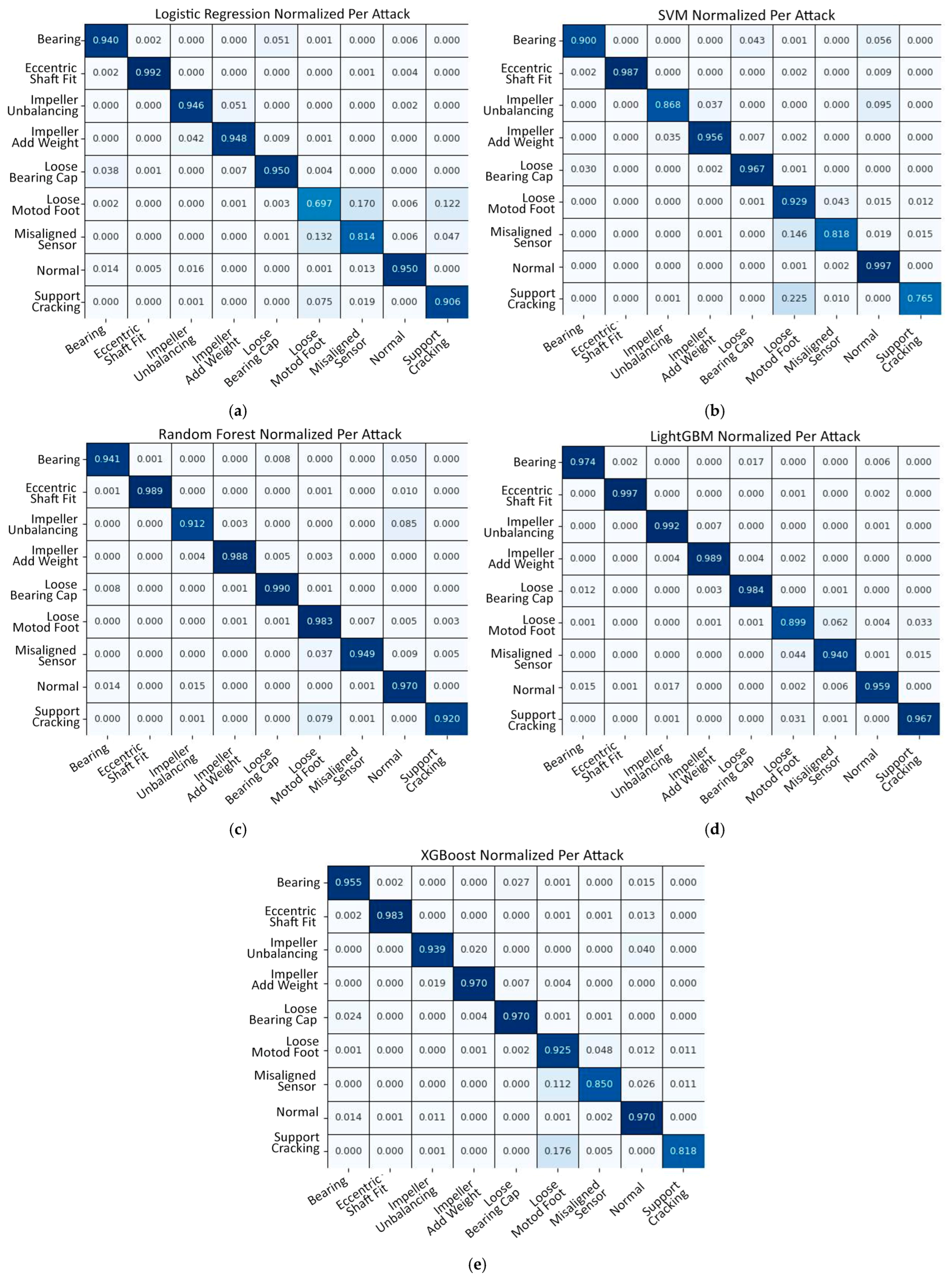

5. Defense Strategy

5.1. Adversarial Training by Transfer Learning

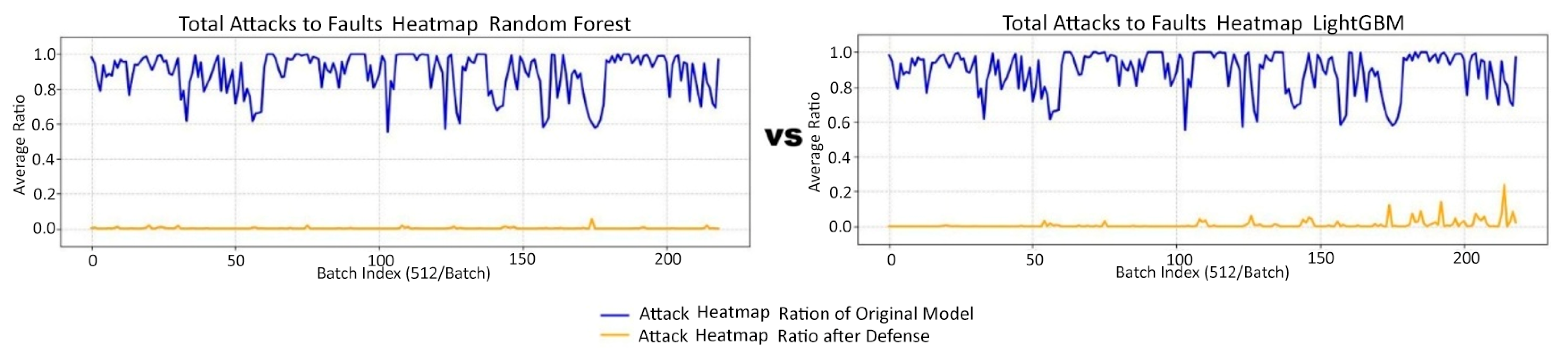

5.2. Confusion Matrices, Heatmaps, and Evaluation Metrics

- Training time reflects the computational expense of preparing each classifier for deployment, highlighting how feasible it is to retrain models when new data becomes available [58].

- Inference latency time measures the time required to obtain predictions on the test set, directly linking to the responsiveness of the system in real-world operation [59].

- Complementing this, inference throughput expresses how many samples can be processed per second, which is critical in environments with high-frequency sensor data and large-scale monitoring tasks [60].

- Finally, model size quantifies the storage footprint of the trained classifier, determining whether it can be efficiently deployed on devices with limited memory, such as PLCs or embedded controllers [61].

6. Discussion, Limitations, and Future Work

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MCII | Mean Confusion Impact Index |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| DL | Deep learning |

| FGSM | Fast Gradient Sign Method |

| PGD | Projected Gradient Descent |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| LSTMs | Long Short-Term Memories |

| SAEM | Spectrogram-Aware Ensemble Method |

| ICS | Industrial control systems |

| FTEP | Tennessee Eastman Process |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MSMQ | Microsoft Message Queuing Services |

| aRMS | Acceleration Root Mean Square |

| aPeak | Acceleration Peak |

| vRMS | Velocity Root Mean Square |

| CF | Crest Factor |

References

- Salem, K.; AbdelGwad, E.; Kouta, H. Predicting Forced Blower Failures Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Vibration Data for Effective Maintenance Strategies. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2023, 23, 2191–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, Y.; Danouj, B. Survey on Deep Learning Applied to Predictive Maintenance. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2020, 10, 5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Krishna, R.; Ding, Y.; Ray, B. Deep Learning Based Vulnerability Detection: Are We There Yet? IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2022, 48, 3280–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, K.D.; Gkouvrikos, E.V.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Traffic Sign Recognition Robustness in Autonomous Vehicles Under Physical Adversarial Attacks. In Cutting Edge Applications of Computational Intelligence Tools and Techniques. Studies in Computational Intelligence; Daimi, K., Alsadoon, A., Coelho, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 287–304. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Qu, G. Fooling the Eyes of Autonomous Vehicles: Robust Physical Adversarial Examples Against Traffic Sign Recognition Systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 24–28 April 2022; Internet Society: Reston, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Poskitt, C.M.; Sun, J.; Chattopadhyay, S. Physical Adversarial Attack on a Robotic Arm. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 9334–9341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, A.A.; Mehbodniya, A.; Webber, J.L.; Bostani, A.; Shah, B.; Ergashevich, B.Z. Optimizing Intrusion Detection in Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems through Transfer Learning Approaches. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 111, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisopoulos, N.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Machine Learning Robustness in Predictive Maintenance Under Adversarial Attacks. In Proceedings of the Congress on Control, Robotics, and Mechatronics, Rajasthan, India, 25–26 March 2023; pp. 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Thrace Group Thrace Nonwovens; Geosynthetics, S.A. Available online: https://www.thracegroup.com/cz/en/companies/thrace-ng/ (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Naqvi, S.M.A.; Shabaz, M.; Khan, M.A.; Hassan, S.I. Adversarial Attacks on Visual Objects Using the Fast Gradient Sign Method. J. Grid Comput. 2023, 21, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M.L. Trans-IFFT-FGSM: A Novel Fast Gradient Sign Method for Adversarial Attacks. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 72279–72299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayas, M.S.; Ayas, S.; Djouadi, S.M. Projected Gradient Descent Adversarial Attack and Its Defense on a Fault Diagnosis System. In Proceedings of the 2022 45th International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 13–15 July 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Waghela, H.; Sen, J.; Rakshit, S. Robust Image Classification: Defensive Strategies against FGSM and PGD Adversarial Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2024 Asian Conference on Intelligent Technologies (ACOIT), Kolar, India, 6–7 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yan, D. Adversarial Attacks on Machinery Fault Diagnosis. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2110.02498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, W.; Son, Y. Evaluating Practical Adversarial Robustness of Fault Diagnosis Systems via Spectrogram-Aware Ensemble Method. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareapoor, M.; Shamsolmoali, P.; Yang, J. Oversampling Adversarial Network for Class-Imbalanced Fault Diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 149, 107175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, A.K.; Das, A.; Palleti, V.R. Study of Adversarial Attacks on Anomaly Detectors In Industrial Control Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.03120. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas-Ch, W.; Govea, J.; Jaramillo-Alcazar, A. Tamper Detection in Industrial Sensors: An Approach Based on Anomaly Detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 8908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematirad, R.; Behrang, M.; Pahwa, A. Acoustic-Based Online Monitoring of Cooling Fan Malfunction in Air-Forced Transformers Using Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26384–26400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Ge, Z. Adversarial Attacks on Neural-Network-Based Soft Sensors: Directly Attack Output. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 2443–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Chen, Q.; Tong, S.; Liu, H. Knowledge-Aided Generative Adversarial Network: A Transfer Gradient-Less Adversarial Attack for Deep Learning-Based Soft Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), Dalian, China, 5–8 July 2024; 2024; pp. 1254–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Zizzo, G.; Hankin, C.; Maffeis, S.; Jones, K. Adversarial Attacks on Time-Series Intrusion Detection for Industrial Control Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 19th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Guangzhou, China, 29 December 2020–1 January 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 899–910. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Gu, X.; He, J.; Yang, S.; Tu, Y.; Wu, C. A Robust Approach of Multi-Sensor Fusion for Fault Diagnosis Using Convolution Neural Network. J. Dyn. Monit. Diagn. 2022, 1, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farwell, P.; Rohozinski, R. Threats to Industrial Cyber-Physical Systems. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Cyber Conflict CyCon X, NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE), Tallinn, Estonia, 29 May–1 June 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo, J.; Urbina, D.; Cardenas, A.; Valente, J.; Faisal, M.; Ruths, J.; Tippenhauer, N.O.; Sandberg, H.; Candell, R. A Survey of Physics-Based Attack Detection in Cyber-Physical Systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 51, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Kim, H.; Virani, N.; Xu, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, P. Exploiting Physical Dynamics to Detect Actuator and Sensor Attacks in Mobile Robots. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.01834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurakin, A.; Goodfellow, I.J.; Bengio, S. Adversarial Examples in the Physical World. In Artificial Intelligence Safety and Security; Chapman and Hall/CRC: First ed.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Eykholt, K.; Evtimov, I.; Fernandes, E.; Li, B.; Rahmati, A.; Xiao, C.; Prakash, A.; Kohno, T.; Song, D. Robust Physical-World Attacks on Deep Learning Visual Classification. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1625–1634. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Xiao, C.; Cyr, B.; Zhou, Y.; Park, W.; Rampazzi, S.; Chen, Q.A.; Fu, K.; Mao, Z.M. Adversarial Sensor Attack on LiDAR-Based Perception in Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, London, UK, 11–15 November 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2267–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, K.; Fernando, T.; Fookes, C.; Sridharan, S. Physical Adversarial Attacks for Surveillance: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 17036–17056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozdnyakov, V.; Kovalenko, A.; Makarov, I.; Drobyshevskiy, M.; Lukyanov, K. Adversarial Attacks and Defenses in Fault Detection and Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Benchmark on the Tennessee Eastman Process. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2024, 5, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Sun, B.; Wang, Y. A Review on Adversarial–Based Deep Transfer Learning Mechanical Fault Diagnosis. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Dong, X.; Tu, G.; Wang, D.; Cheng, C.; Zhao, B.; Peng, Z. TFN: An Interpretable Neural Network with Time-Frequency Transform Embedded for Intelligent Fault Diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 207, 110952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, H.H.N. Adversarial Machine Learning Attacks on Condition-Based Maintenance Capabilities. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.12097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhuo, Y.; Ge, Z. Transfer Adversarial Attacks across Industrial Intelligent Systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 237, 109299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozdnyakov, V.; Kovalenko, A.; Makarov, I.; Drobyshevskiy, M.; Lukyanov, K. AADMIP: Adversarial Attacks and Defenses Modeling in Industrial Processes. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Third International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 3–9 August 2024; pp. 8776–8779. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, D.; Wu, S.; Jiang, T.; Guo, Y.; Liu, A.; Zhou, J. Adversarial Examples in the Physical World: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2311.01473. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, H.; Zaidi, S.M.T.; Munir, A. Improving Adversarial Robustness Through Adaptive Learning-Driven Multi-Teacher Knowledge Distillation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.20996. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Deng, A.; Deng, M.; Xu, M.; Liu, Y.; Ding, X. A Novel Multiscale Feature Adversarial Fusion Network for Unsupervised Cross-Domain Fault Diagnosis. Measurement 2022, 200, 111616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.-M.; Fawzi, A.; Frossard, P. DeepFool: A Simple and Accurate Method to Fool Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NM, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 2574–2582. [Google Scholar]

- Polymeropoulos, I.; Bezyrgiannidis, S.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Bridging AI and Maintenance: Fault Diagnosis in Industrial Air-Cooling Systems Using Deep Learning and Sensor Data. Under Rev. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Moukari, M.; Simon, L.; Picard, S.; Jurie, F. N-MeRCI: A New Metric to Evaluate the Correlation Between Predictive Uncertainty and True Error. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.07253. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, D.; Miller, D.; Capra, J.; Bradley, A.P. Never Mind the Metrics-What about the Uncertainty? Visualising Binary Confusion Matrix Metric Distributions to Put Performance in Perspective. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 202, 22702–22757. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.; Gal, Y. Understanding Measures of Uncertainty for Adversarial Example Detection. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.08533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Xiao, Y.; Chang, X.; Huang, P.-Y.; Li, Z.; Gupta, B.B.; Chen, X.; Wang, X. A Survey of Deep Active Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Pleiss, G.; Sun, Y.; Weinberger, K.Q. On Calibration of Modern Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2017, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 1321–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Abomakhelb, A.; Jalil, K.A.; Buja, A.G.; Alhammadi, A.; Alenezi, A.M. A Comprehensive Review of Adversarial Attacks and Defense Strategies in Deep Neural Networks. Technologies 2025, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A Survey on Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2010, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2018, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, P.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, C.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J. Increasing Interpretability and Feasibility of Data Driven-Based Unknown Fault Diagnosis in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0471722146. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, D.; Wang, B. A Fault Diagnosis Method of Rotating Machinery Based on Improved Multiscale Attention Entropy and Random Forests. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 112, 1191–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Nice, France, 2017; pp. 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Widodo, A.; Yang, B.-S. Support Vector Machine in Machine Condition Monitoring and Fault Diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2007, 21, 2560–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justus, D.; Brennan, J.; Bonner, S.; McGough, A.S. Predicting the Computational Cost of Deep Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Seattle, WA, USA, 10–13 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Networks with Pruning, Trained Quantization and Huffman Coding. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2016-Conference Track Proceedings, San Juan, PR, USA, 2–4 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, D.; Shoeybi, M.; Casper, J.; LeGresley, P.; Patwary, M.; Korthikanti, V.; Vainbrand, D.; Kashinkunti, P.; Bernauer, J.; Catanzaro, B.; et al. Efficient Large-Scale Language Model Training on GPU Clusters Using Megatron-LM. In Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, Saint Louis, MS, USA, 14–19 November 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sze, V.; Chen, Y.-H.; Yang, T.-J.; Emer, J.S. Efficient Processing of Deep Neural Networks: A Tutorial and Survey. Proc. IEEE 2017, 105, 2295–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Main Approach and Findings | Comparison with Present Work |

|---|---|---|

| [14] | Demonstrated that CNN and LSTM models suffer severe accuracy degradation when subjected to FGSM/PGD adversarial perturbations on bearing vibration data. | This work shows that similar vulnerabilities arise under physical perturbations (e.g., sensor misalignment, loose fittings) in an industrial ventilator, extending these findings from digital to real-world conditions. |

| [15] | Proposed a spectral-domain adversarial example method to craft more realistic black-box attacks on bearing datasets. | Unlike SAEM, which remains restricted to digital spectral manipulation, the present study demonstrates that comparable vulnerabilities emerge through real mechanical alterations under industrial operating conditions. |

| [16] | Introduced a GAN-based method for oversampling minority fault classes in bearing FD, mitigating class imbalance. | MoGAN addresses class distribution issues rather than adversarial robustness. The present work highlights how physical perturbations systematically bias diagnostic models, leading to consistent misclassifications. |

| [17] | Showed that LSTM and GRU anomaly detectors in ICS are highly vulnerable to adversarial inputs in simulations. | Similar vulnerabilities are identified here, but in industrial FD models (ResNet50-1D, BiLSTM) under physical adversarial conditions in a production plant. |

| [18] | Demonstrated that small-scale physical sabotage on ICS testbeds can bypass anomaly detection mechanisms. | While Villegas-Ch et al. addressed ICS security, this work applies the concept of physical adversarial interference specifically to vibration-based FD in real production equipment. |

| [20] | Proposed label-free black-box adversarial attacks on soft sensors, showing that regression outputs can be manipulated without ground-truth labels. | The present study extends this concept of stealthy perturbation to vibration-based FD, where physical interventions on sensors mislead classifiers without altering the true operational condition. |

| [21] | Developed a knowledge-aware GAN to generate smooth adversarial perturbations for soft sensor data in process simulations. | Whereas KAGAN focuses on simulated adversarial smoothness, the perturbations examined here arise naturally from mechanical interventions (eccentric shaft fit, loose bearing) in a real industrial system. |

| [23] | Proposed multi-sensor fusion (vibration and acoustic) to enhance robustness against random noise in bearings. | Similarly, this work integrates multi-feature inputs (vibration and operational features) but shows that such integration improves resilience against intentional physical adversarial perturbations, not only random noise. |

| [31] | Benchmarked defenses (adversarial training, denoising, ensembles) on the Tennessee Eastman Process; found adversarial training most effective in black-box scenarios. | That benchmark is process-simulation–oriented. This study introduces a new benchmark in rotating machinery, shifting robustness evaluation from simulated processes to real mechanical FD under physical attacks. |

| [32] | Reviewed adversarial transfer learning and emphasized its persistent vulnerabilities across domains. | This study empirically validates those observations: while the frozen ResNet50-1D backbone is vulnerable, robustness is enhanced by retraining lightweight ML heads (RF/LightGBM) with adversarial data, as quantified by the MCII metric. |

| [33] | Developed a Time–Frequency Network that improves noise robustness and interpretability in bearing FD. | TFN addresses stochastic disturbances, whereas the present study focuses on systematic adversarial perturbations in industrial machinery, offering complementary insights. |

| Model | Acc% | Loss% | Prec% | Rec% | F1% | MCII% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet50 | 97.8 | 3.7 | 97.5 | 97.8 | 97.6 | 67.3 |

| CNN-1D | 97.3 | 8.4 | 98.0 | 94.8 | 96.4 | 67.8 |

| BiLSTM | 97.8 | 6.0 | 98.8 | 95.5 | 97.1 | 70.0 |

| 2BiLSTM+Attention | 97.6 | 5.6 | 98.9 | 95.5 | 97.1 | 71.7 |

| Model | Accuracy% | Precision% | Recall% | F1-Score% | MCII% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet50-1D + Log. Reg. | 91.78 | 86.08 | 90.48 | 87.72 | 4.88 |

| ResNet50-1D + SVM | 94.81 | 93.94 | 90.97 | 92.31 | 2.30 |

| ResNet50-1D + RF | 96.53 | 96.78 | 96.00 | 96.37 | 0.14 |

| ResNet50-1D + LGBM | 96.30 | 93.94 | 96.68 | 95.21 | 0.90 |

| ResNet50-1D + XGB | 95.25 | 93.88 | 93.13 | 93.46 | 1.37 |

| Classifier Head | Training Time (s) | Inference Latency (s/Test) | Throughput (Samples/s) | Model Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 112.65 | 0.2858 | 280,220 | 276.15 MB |

| XGBoost | 26.10 | 0.3239 | 247,291 | 3.10 MB |

| LightGBM | 21.13 | 1.9187 | 41,741 | 3.00 MB |

| Logistic Regression | 143.18 | 0.0252 | 3,174,606 | 8.17 KB |

| SVM | 4435.05 | 518.81 | 154.4 | 39.18 MB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bezyrgiannidis, S.; Polymeropoulos, I.; Vrochidou, E.; Papakostas, G.A. Exposing Vulnerabilities: Physical Adversarial Attacks on AI-Based Fault Diagnosis Models in Industrial Air-Cooling Systems. Processes 2025, 13, 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092920

Bezyrgiannidis S, Polymeropoulos I, Vrochidou E, Papakostas GA. Exposing Vulnerabilities: Physical Adversarial Attacks on AI-Based Fault Diagnosis Models in Industrial Air-Cooling Systems. Processes. 2025; 13(9):2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092920

Chicago/Turabian StyleBezyrgiannidis, Stavros, Ioannis Polymeropoulos, Eleni Vrochidou, and George A. Papakostas. 2025. "Exposing Vulnerabilities: Physical Adversarial Attacks on AI-Based Fault Diagnosis Models in Industrial Air-Cooling Systems" Processes 13, no. 9: 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092920

APA StyleBezyrgiannidis, S., Polymeropoulos, I., Vrochidou, E., & Papakostas, G. A. (2025). Exposing Vulnerabilities: Physical Adversarial Attacks on AI-Based Fault Diagnosis Models in Industrial Air-Cooling Systems. Processes, 13(9), 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13092920