From Viability to Resilience: Technical–Economic Insights into Palm Oil Production Using a FP2O Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Process Description

2.2. Considerations of Technical–Economic Evaluation for Crude Palm Oil Production Process

2.3. Technical–Economic Evaluation for Crude Palm Oil Production Process

2.4. Technical–Economic Resilience via FP2O Methodology for Crude Palm Oil Production Process

3. Results and Discussion

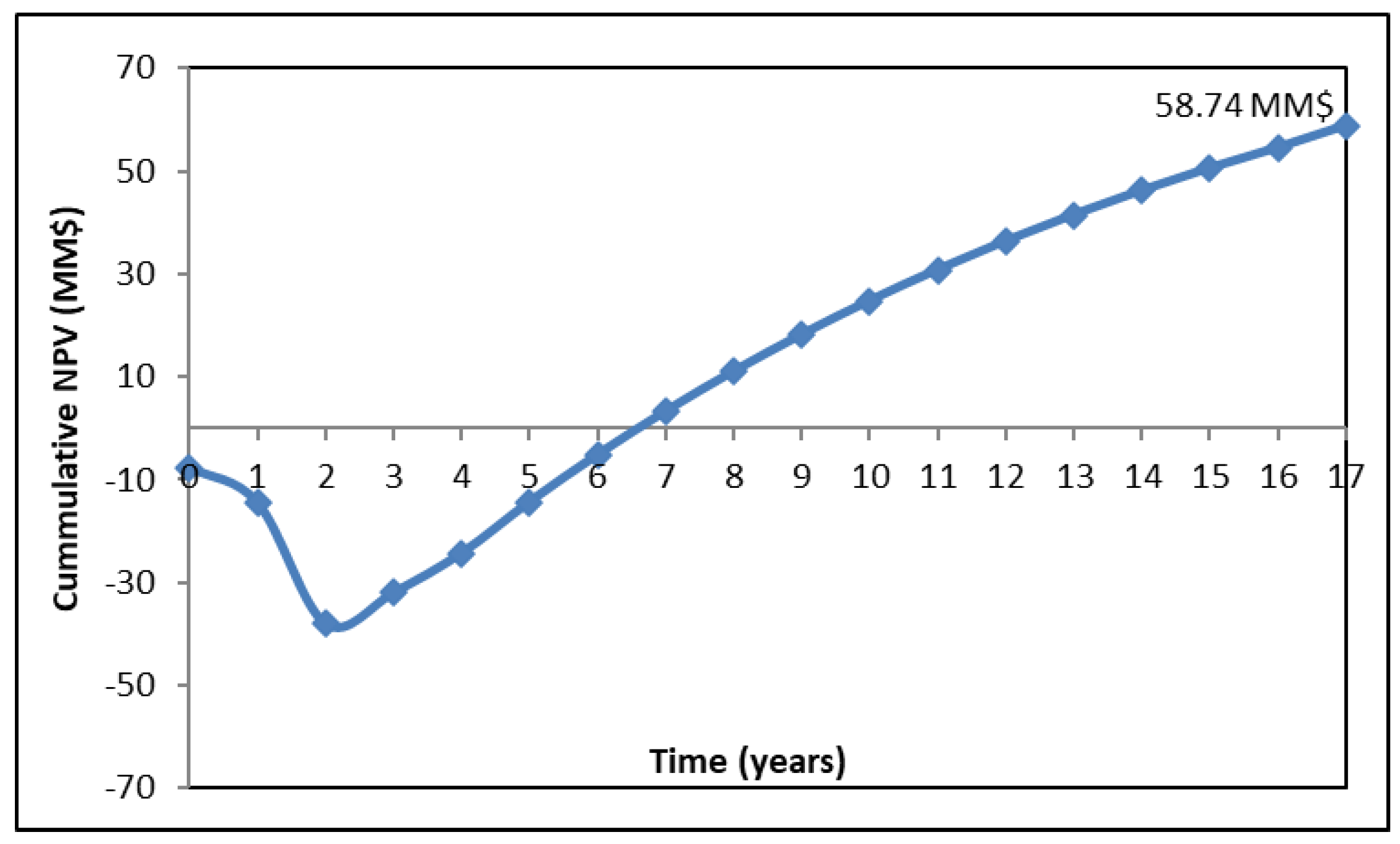

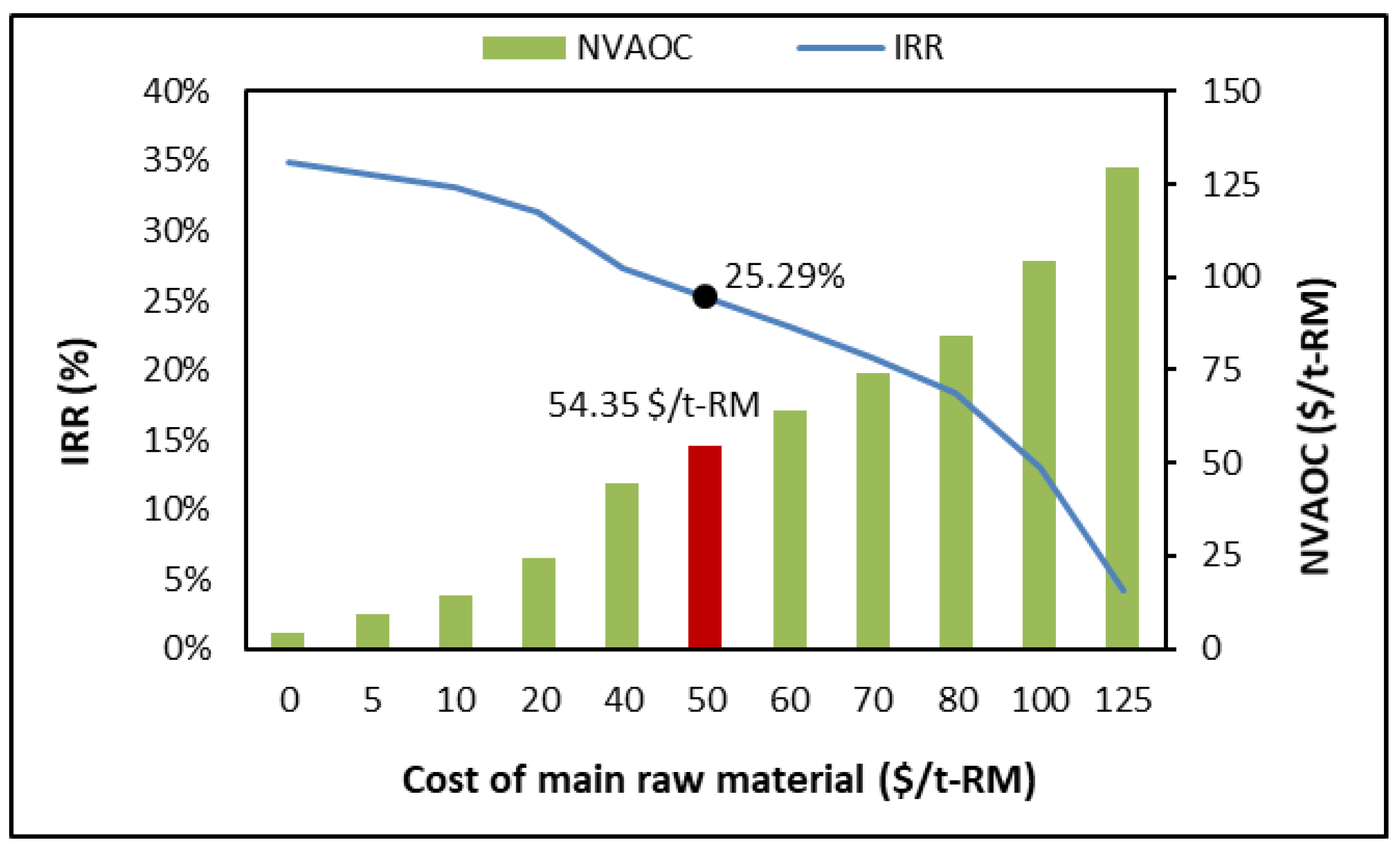

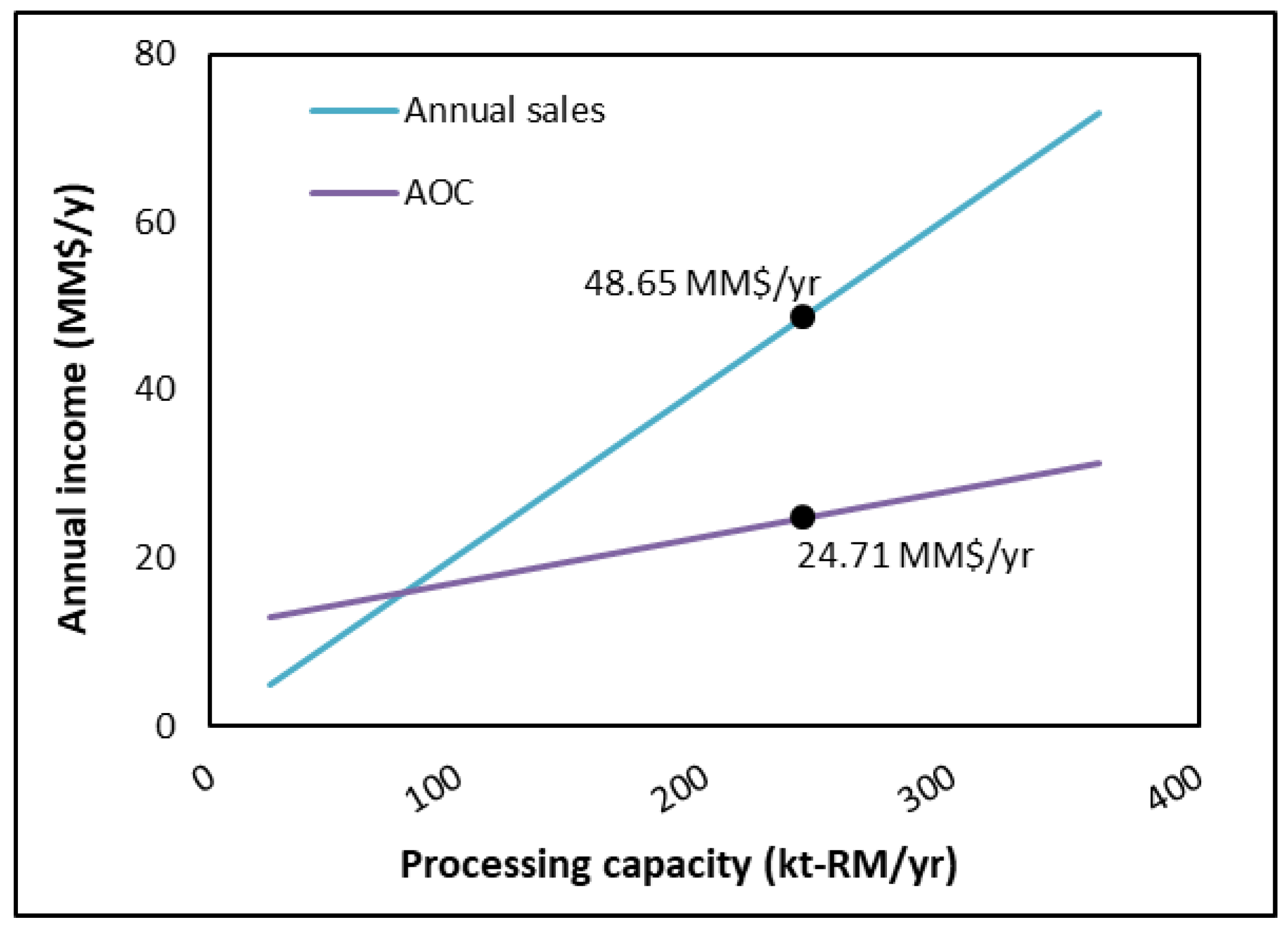

3.1. Analysis of the Technical–Economic Evaluation of Crude Palm Oil Production Process

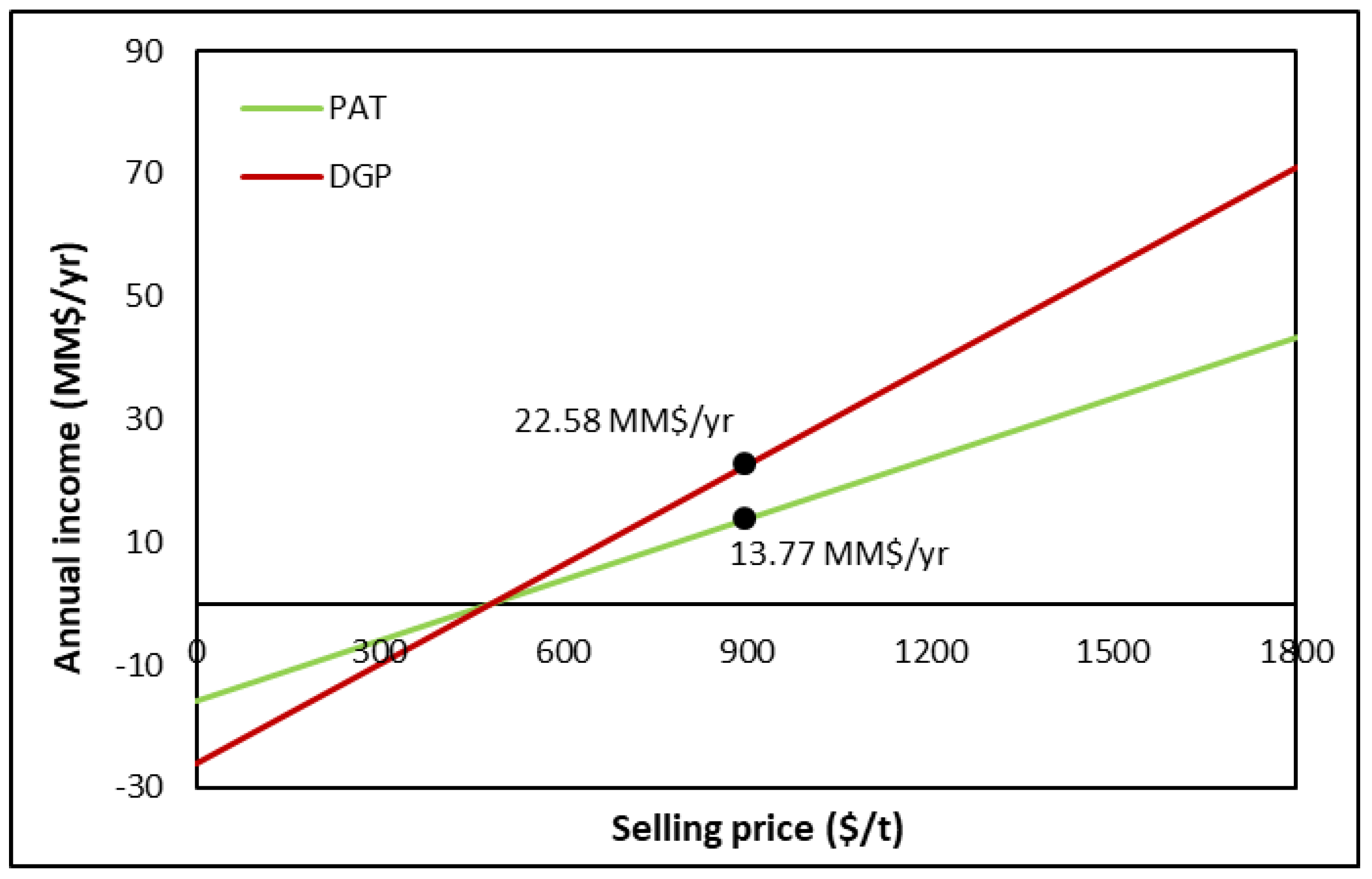

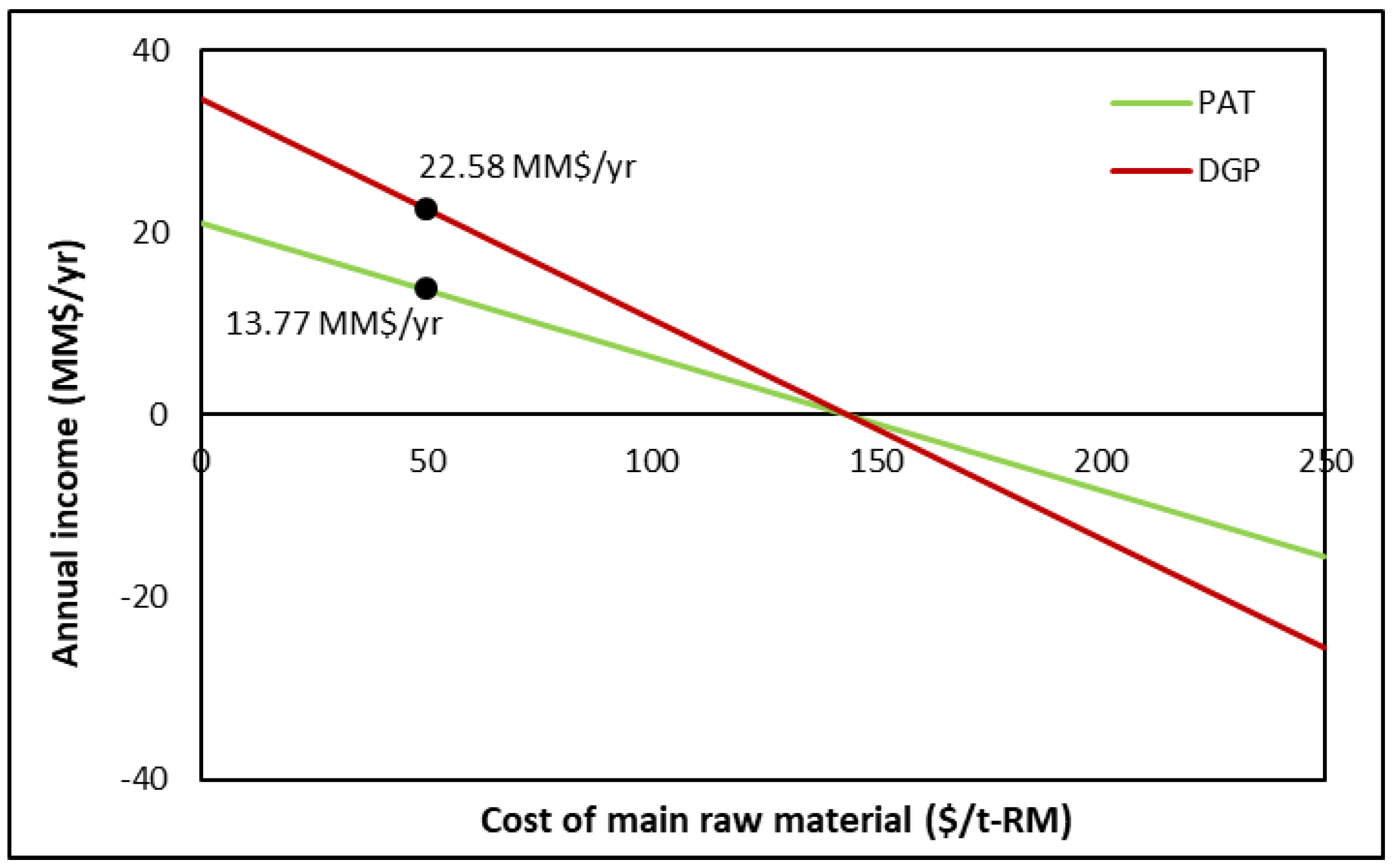

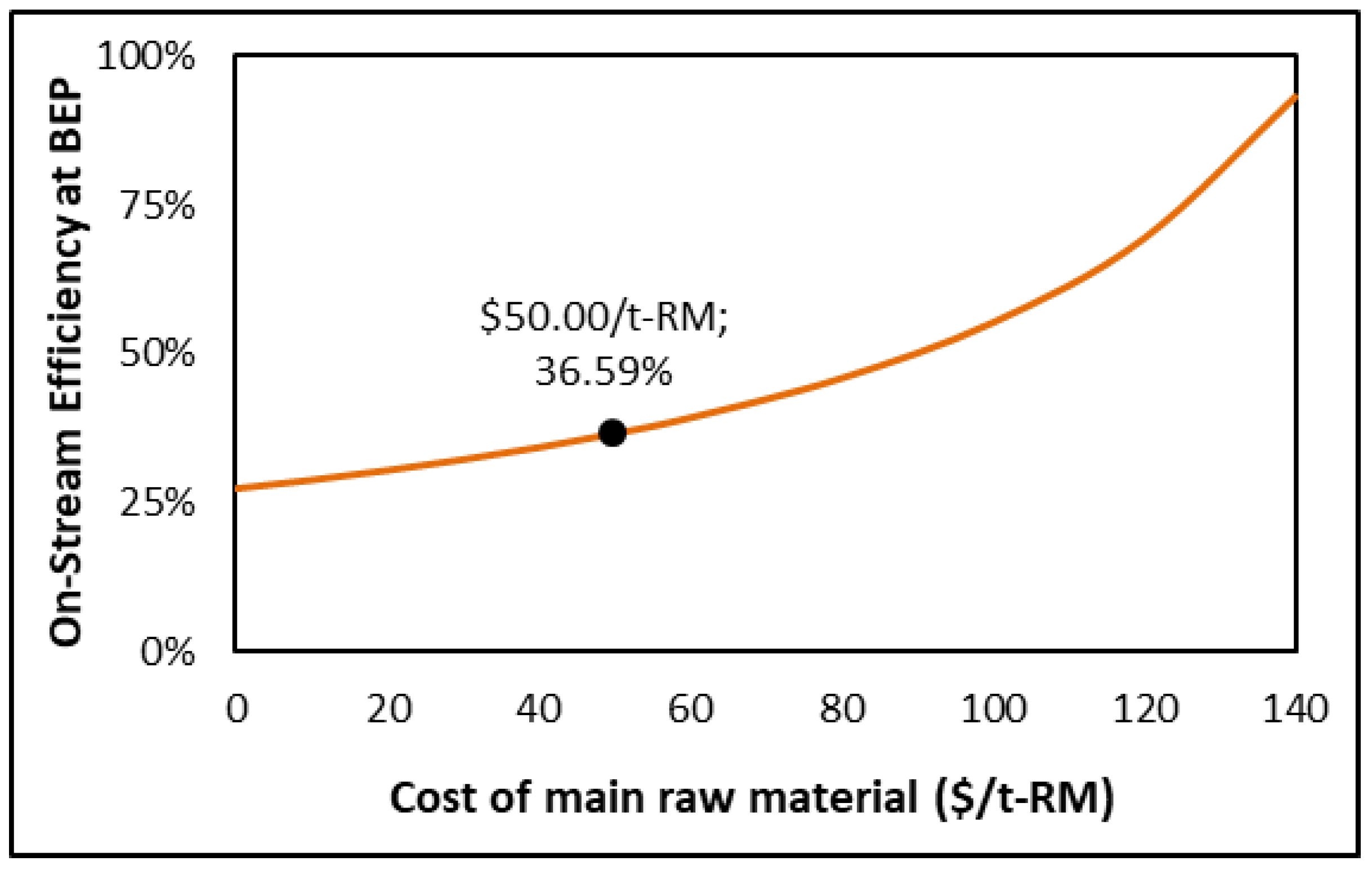

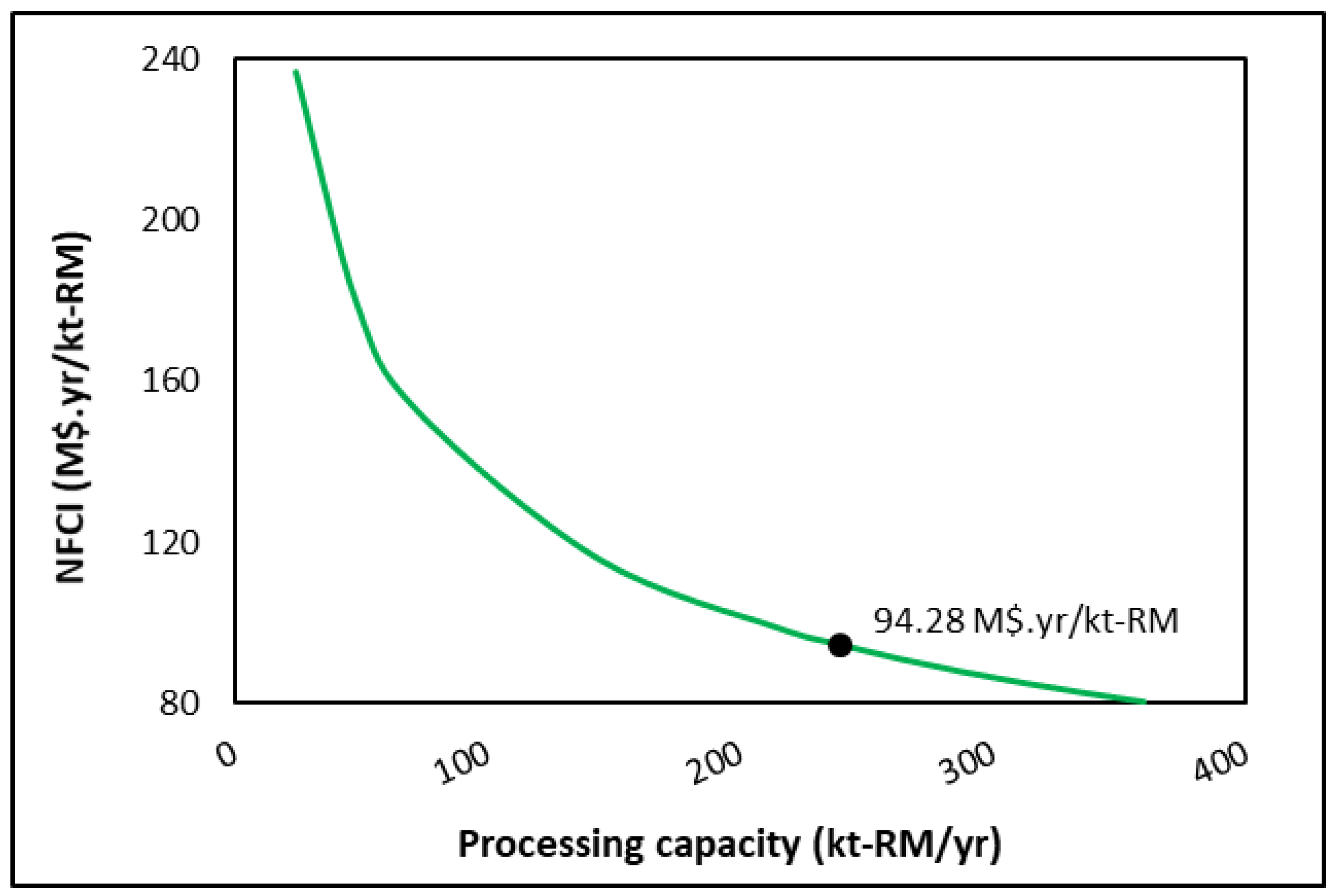

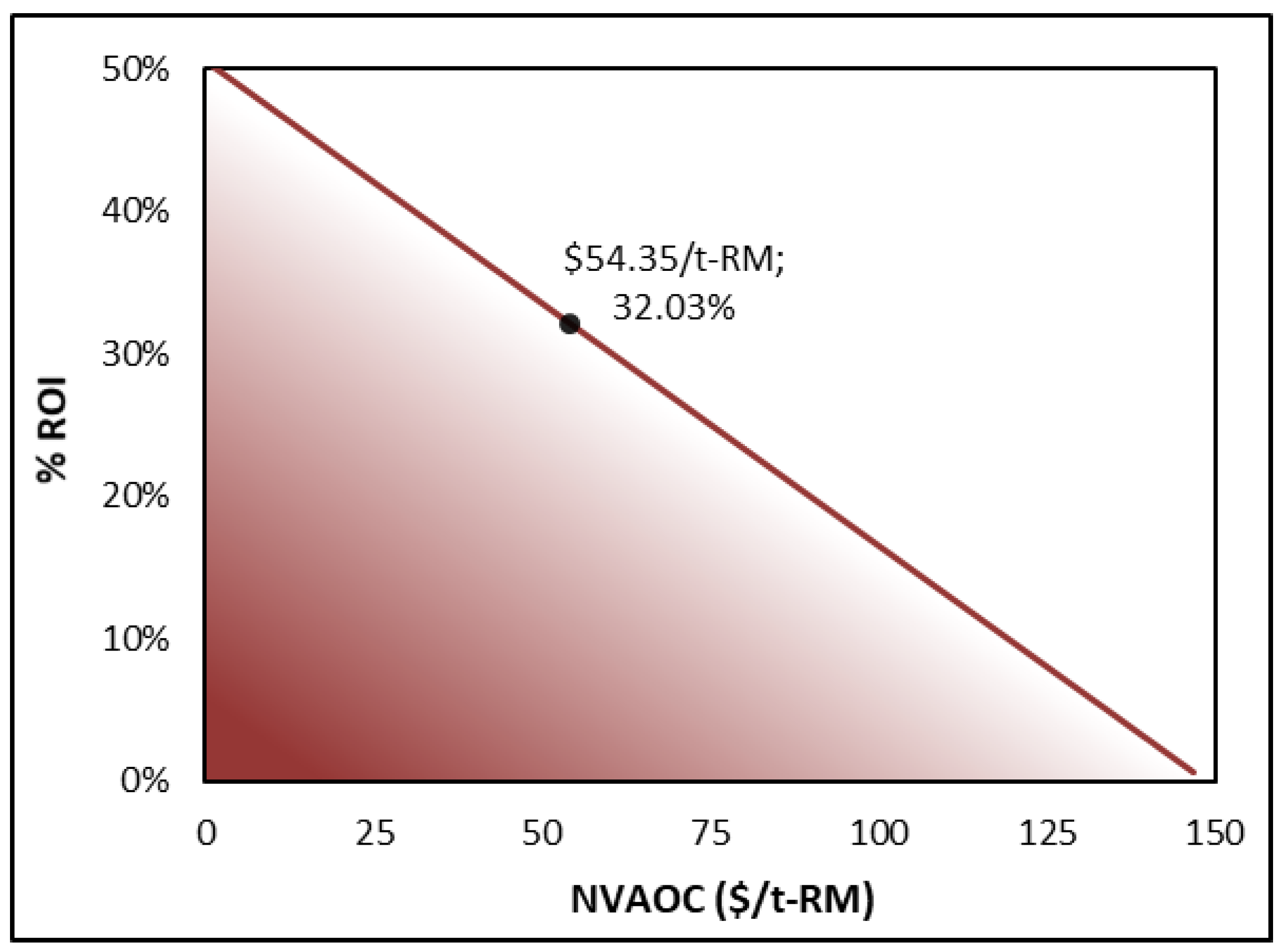

3.2. Analysis of Technical–Economic Resilience Through the FP2O Methodology of the Crude Palm Oil Production Process

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alhaji, A.M.; Almeida, E.S.; Carneiro, C.R.; da Silva, C.A.S.; Monteiro, S.; Coimbra, J.S.d.R. Palm Oil (Elaeis Guineensis): A Journey through Sustainability, Processing, and Utilization. Foods 2024, 13, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urugo, M.M.; Teka, T.A.; Teshome, P.G.; Tringo, T.T. Palm Oil Processing and Controversies over Its Health Effect: Overview of Positive and Negative Consequences. J. Oleo Sci. 2021, 70, 1693–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigetomi, Y.; Ishimura, Y.; Yamamoto, Y. Trends in Global Dependency on the Indonesian Palm Oil and Resultant Environmental Impacts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mba, O.I.; Dumont, M.J.; Ngadi, M. Palm Oil: Processing, Characterization and Utilization in the Food Industry—A Review. Food Biosci. 2015, 10, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia, J.C.; Jangam, S.V.; Akhtar, S.; Sasmito, A.P.; Mujumdar, A.S. Advances in Biofuel Production from Oil Palm and Palm Oil Processing Wastes: A Review. Biofuel Res. J. 2016, 3, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, H.; Okarda, B.; Dermawan, A.; Ilham, Q.P.; Pacheco, P.; Nurfatriani, F.; Suhendang, E. Reconciling Oil Palm Economic Development and Environmental Conservation in Indonesia: A Value Chain Dynamic Approach. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 111, 102089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo, A.M.; Alves, A.S.B.; da Silva, E.F.; Krumreich, F.D.; Nunes, I.L.; Ribeiro, C.D.F. Perception, Knowledge, and Consumption Potential of Crude and Refined Palm Oil in Brazilian Regions. Foods 2024, 13, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.J.; Goggin, K.; Paterson, R.R.M. Oil Palm in the 2020s and beyond: Challenges and Solutions. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2021, 2, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahza, A.; Tampubolon, D.; Irianti, M.; Meiwanda, G.; Asmit, B. The Impact of Small-Scale Oil Palm Plantation Development on the Economy Multiplier Effect and Rural Communities Welfare. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoh, E.T.; Kiplagat, J.; Kimutai, S.K.; Mecha, A.C. Current Trends in Palm Oil Waste Management: A Comparative Review of Cameroon and Malaysia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifin, A.; Feryanto; Herawati; Harianto. Assessing the Impact of Limiting Indonesian Palm Oil Exports to the European Union. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TO, O.; O, A.; PO, O.; Olatubi, I.V.; VA, A.; EA, A. Environmental Impact of Oil Palm Processing on Some Properties of the On-Site Soil in a Growing City in Nigeria. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 918478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondi, M.H.; Haris, N.I.N.; Shamsudin, R.; Yunus, R.; Mohd Ali, M.; Iswardi, A.H. Development and Testing of an Oil Palm (Elaeis Guineensis Jacq.) Fruit Digester Process for Kernel Free in Crude Palm Oil Production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 208, 117755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Rodríguez, T.C.; Ramos-Olmos, M.; González-Delgado, Á.D. A Joint Economic Evaluation and FP2O Techno-Economic Resilience Approach for Evaluation of Suspension PVC Production. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.C.R.; Echeverry, L.A.V.; Peralta-Ruiz, Y.Y.; González-Delgado, A.D. A Techno-Economic Sensitivity Approach for Development of a Palm-Based Biorefineries in Colombia. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 57, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Kim, K.; Kim, K.H.; Kang, S. Techno-Economic Analysis and Monte Carlo Simulation for Green Hydrogen Production Using Offshore Wind Power Plant. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 263, 115695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Li, D.; Zhang, D. An AI Agent for Techno-Economic Analysis of Anaerobic Co-Digestion in Renewable Energy Applications. Energies 2025, 18, 5632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Maza, S.; Rojas-Flores, S.; González-Delgado, Á.D. Technical Insights into Crude Palm Oil (CPO) Production Through Water–Energy–Product (WEP) Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedepalma. Federación Nacional de Cultivadores de Palma de Aceite. 2022. Available online: https://fedepalma.org/ (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Wibowo, L.S. Factor Influencing Crude Palm Oil (CPO) Biodiesel Supply in Indonesia Using Error Correction Model (ECM). Bus. Econ. Res. 2015, 5, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, D.; Puerta, A.; Mestre, R.; Peralta-Ruiz, Y.; Gonzalez-Delgado, A.D. Exergy-Based Evaluation of Crude Palm Oil Production in North-Colombia. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2016, 10, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ajith, B.S.; Manjunath Patel, G.C.; Der, O.; Selvan, C.P.; Samuel, O.D.; Annadurai, S.; Thajudeen, K.Y.; Yadav, K.K. Microwave-Assisted Transesterification of Hybrid Garcinia Gummi-Gutta and Garcinia Indica Oils: Optimization Using RSM and Meta-Heuristic Algorithms for High-Yield Biodiesel Production. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 202, 108223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Samuel, O.D.; Patel G C, M.; Der, O.; Abbas, M.; Hussain, F.; Ting, T.T. Enhancing CI Engine Performance and Emission Control Using a Hybrid RSM–Rao Algorithm for ZnO-Doped Castor–Neem Biodiesel Blends. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 74, 106841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, Á.D. Computer-Assisted Hira Assessment of Hazardous in the Production of Crude Palm Oil. 2019. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122609/records/68877c277fd4d06c32a8c993 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Peters, M.S.; Timmerhaus, K.D.; West, R.E. Plant Design and Economics for Chemical Engineers; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Swift Valuation Services. Inventory Index Factors; Freestone Central Appraisal District: Fairfield, TX, USA, 2025.

- El-Halwagi, M.M. Sustainable Design Through Process Integration: Fundamentals and Applications to Industrial Pollution Prevention, Resource Conservation, and Profitability Enhancement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dermoredjo, S.K.; Darmawan, D.H.A.; Sumedi; Mutaqin; Dani, F.Z.D.P.; Yusuf, E.S.; Pasaribu, S.M.; Sayaka, B.; Wardana, I.P.; Adnyana, I.M.O.; et al. The Global Sway of Indonesian Palm Oil: An Export Analysis. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 22, 102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryati, Z.; Subramaniam, V.; Noor, Z.Z.; Hashim, Z.; Loh, S.K.; Aziz, A.A. Social Life Cycle Assessment of Crude Palm Oil Production in Malaysia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliesnichenko, A.S. EBIT and EBITDA Measures in Company Accounting and Reporting. 2018. Available online: https://nubip.edu.ua/sites/default/files/zbirnik_0.pdf#page=26 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Sulin, S.N.; Mokhtar, M.N.; Baharuddin, A.S.; Mohammed, M.A.P. Simulation and Techno-Economic Evaluation of Integrated Palm Oil Mill Processes for Advancing a Circular Economy. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 19, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Fresh fruit bunches flow (t/year) | 240,000 |

| Crude palm oil flow (t/year) | 54,056 |

| Fresh fruit bunches cost (USD/t) | 50 |

| Crude palm oil cost (USD/t) | 900 |

| Plant life (years) | 15 |

| Salvage value | 10% of the Fixed Capital Investment (FCI) subject to depreciation |

| Construction time | 2 years |

| Location | Colombia |

| Tax rate | 39% |

| Discount rate | 8.7% |

| Capacity operated | Half of the total in the first year, rising to seventy percent in the second, and reaching full implementation from the third year forward |

| Process type | Proven process |

| Process control | Digital |

| Type of project | Facility built on undeveloped land |

| Type of soil | Soft clay |

| Contingency percentage (%) | 60 |

| Tank design code | ASME |

| Vessel diameter specification | Internal diameter |

| Operator hour cost (USD/h) | 30 |

| Supervisor hourly cost (USD/h) | 35 |

| Salaries per year | 13 |

| Utilities | Natural gas, steam, water and electricity |

| Process fluids | Solid, gas and liquid |

| Depreciation method | Linear |

| Item | Total |

|---|---|

| Cost of equipment (USD) | 3,743,556.96 |

| Delivered purchased equipment cost (USD) | 4,492,268.35 |

| Purchased equipment (installed; USD) | 1,347,680.51 |

| Instrumentation (installed; USD) | 539,072.20 |

| Piping (installed; USD) | 1,347,680.51 |

| Electrical network (installed; USD) | 853,530.99 |

| Buildings (including services; USD) | 2,246,134.18 |

| Services facilities (installed; USD) | 1,796,907.34 |

| Total DFCI (USD) | 12,623,274.07 |

| Land (USD) | 269,536.10 |

| Land improvements (USD) | 1,796,907.34 |

| Engineering and supervision (USD) | 2,335,979.54 |

| Equipment (R+D; USD) | 449,226.84 |

| Construction costs (USD) | 1,527,371.24 |

| Legal expenses (USD) | 44,922.68 |

| Contractors’ fees (USD) | 883,629.18 |

| Contingency (USD) | 2,695,361.01 |

| Total IFCI (USD) | 10,002,933.94 |

| Fixed capital investment (FCI; USD) | 22,626,208.01 |

| Working capital (WCI; USD) | 18,100,966.41 |

| Start-up (SUC; USD) | 2,262,620.80 |

| Total capital investment (TCI; USD) | 42,989,795.22 |

| Salvage value FCI (USD) | 2,235,667.19 |

| Annualized fixed costs (AFC; USD/year) | 1,359,369.39 |

| Item | Total $/year |

|---|---|

| Raw materials | 12,000,000.00 |

| Industrial services | 1,044,600.00 |

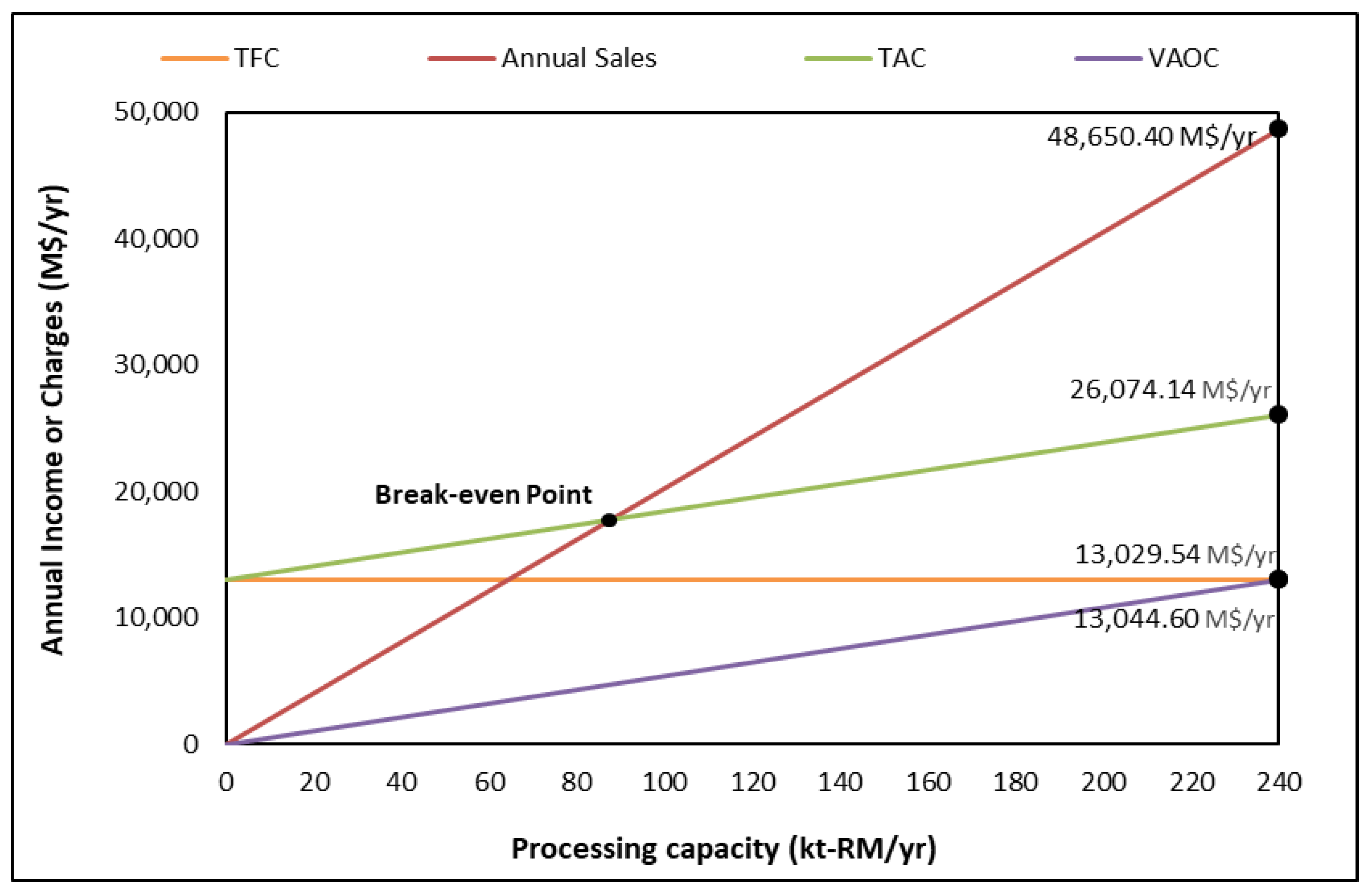

| Total VAOC | 13,044,600.00 |

| Local taxes | 678,786.24 |

| Insurance | 226,262.08 |

| Interest/rent | 429,897.95 |

| Total FCH | 1,334,946.27 |

| Maintenance and repairs | 1,131,310.40 |

| Operating supplies | 169,696.56 |

| Operating labor | 3,643,733.33 |

| Direct supervision and office work | 546,560.00 |

| Laboratory charges | 364,373.33 |

| Patents and royalties | 226,262.08 |

| Total DPC | 6,081,935.71 |

| Overhead (POH) | 2,186,240.00 |

| General expenses (GE) | 2,067,043.93 |

| Total FAOC | 11,670,165.91 |

| Annualized operating costs (AOC) | 24,714,765.91 |

| Indicator | Total |

|---|---|

| Gross profit (depreciation not included) (GP; USD) | 23,935,634.09 |

| Gross profit (depreciation included) (DGP; USD) | 22,576,264.71 |

| Profitability after tax (PAT; USD) | 13,771,521.47 |

| Economic potential 1 (EP1; USD/year) | 36,650,400.00 |

| Economic potential 2 (EP2; USD/year) | 35,605,800.00 |

| Economic potential 3 (EP3; USD/year) | 23,935,634.09 |

| Cumulative cash flow (CCF; 1/year) | 0.56 |

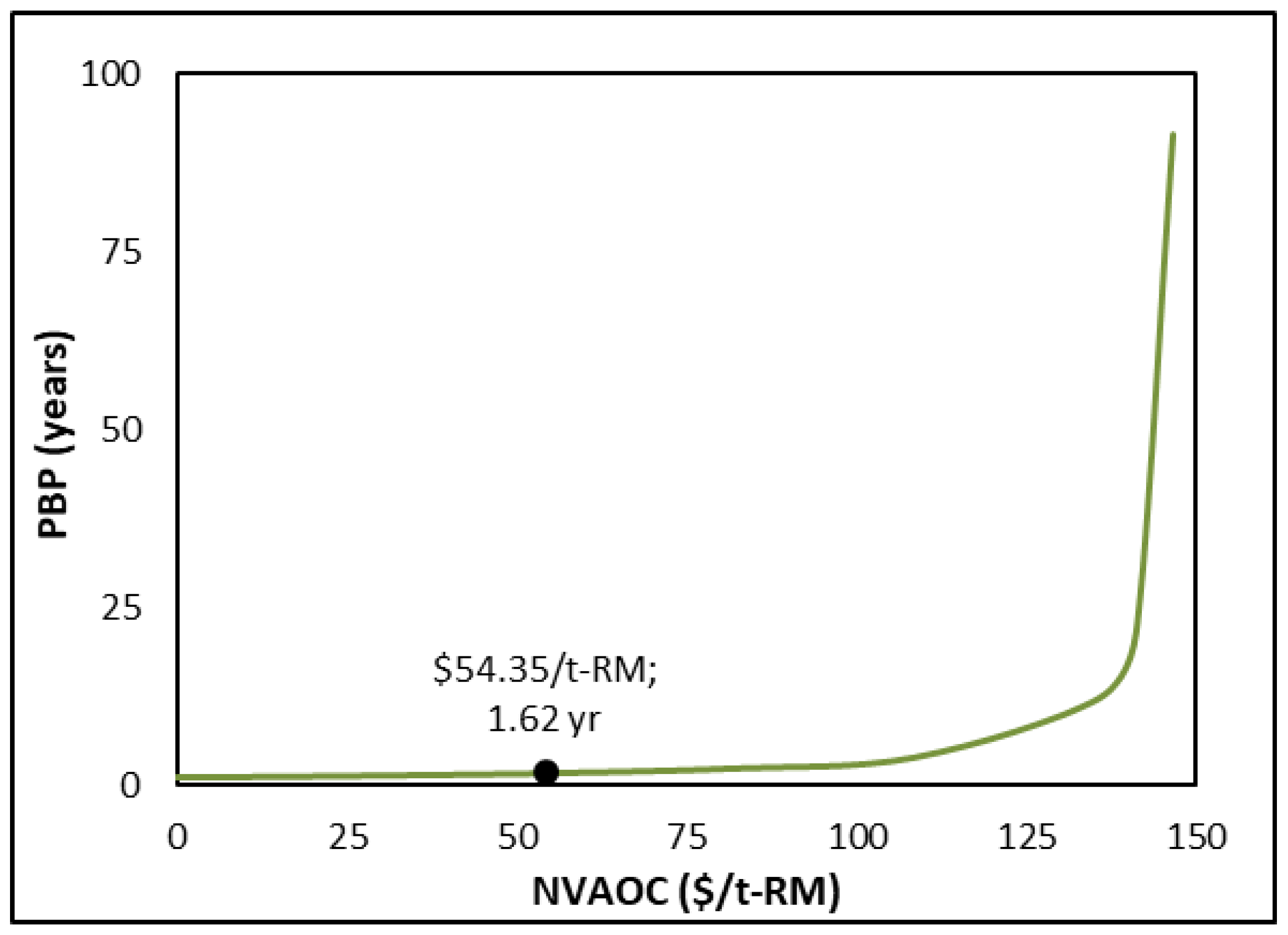

| Payback period (PBP; years) | 1.62 |

| Depreciable payback period (DPBP; years) | 4.88 |

| Return on investment (% ROI) | 32.03 |

| Net present value (NPV; MMUSD) | 58.74 |

| Annual cost/benefit (ACR) | 7.16 |

| Internal rate of return (% IRR) | 25.29 |

| Normalized variable operating costs (NVAOC; USD/t-RM) | 54.35 |

| Capacity at BEP (t-RM/yr) | 87,825.26 |

| Selling price at BEP ($/t) | 482.35 |

| On-stream at BEP (%) | 36.59 |

| Time at BEP (h/yr) | 2927.51 |

| Indicator | Total |

|---|---|

| Earnings before taxes (EBT; USD) | 23,935,634.09 |

| Earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT; USD) | 23,505,736.14 |

| Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA; USD) | 25,295,003.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Maza, S.; Rojas-Flores, S.; González-Delgado, Á.D. From Viability to Resilience: Technical–Economic Insights into Palm Oil Production Using a FP2O Approach. Processes 2025, 13, 4056. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124056

García-Maza S, Rojas-Flores S, González-Delgado ÁD. From Viability to Resilience: Technical–Economic Insights into Palm Oil Production Using a FP2O Approach. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4056. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124056

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Maza, Sofía, Segundo Rojas-Flores, and Ángel Darío González-Delgado. 2025. "From Viability to Resilience: Technical–Economic Insights into Palm Oil Production Using a FP2O Approach" Processes 13, no. 12: 4056. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124056

APA StyleGarcía-Maza, S., Rojas-Flores, S., & González-Delgado, Á. D. (2025). From Viability to Resilience: Technical–Economic Insights into Palm Oil Production Using a FP2O Approach. Processes, 13(12), 4056. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124056