Analysis of Inherent Chemical and Process Safety for Biohydrogen Production from African Palm Rachis via Direct Gasification and Selexol Purification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Process Description

2.2. Process Safety Evaluation

2.3. Chemical Index of Inherent Safety (ICI)

2.4. Inherent Process Safety Index (IPI)

3. Results and Discussion

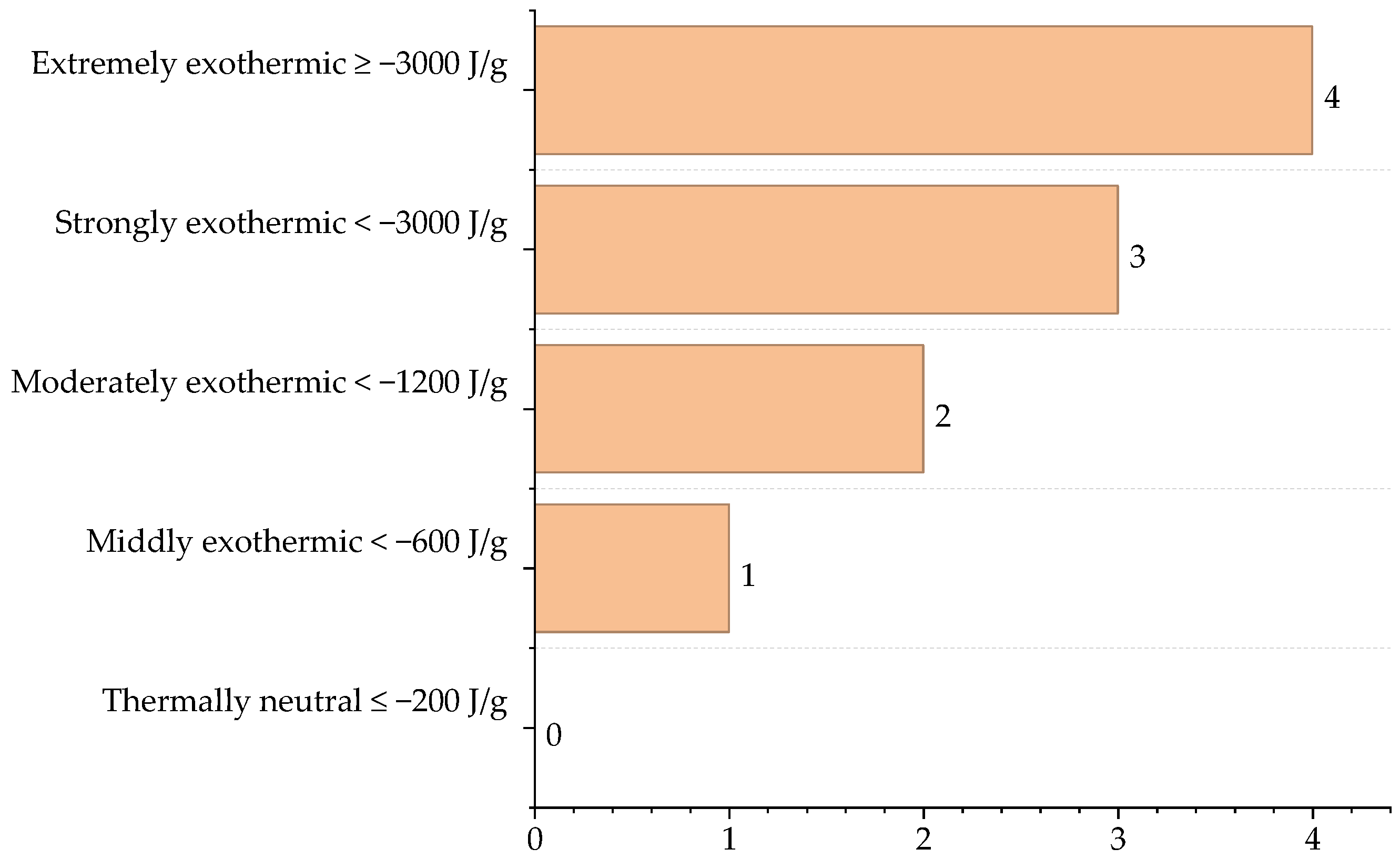

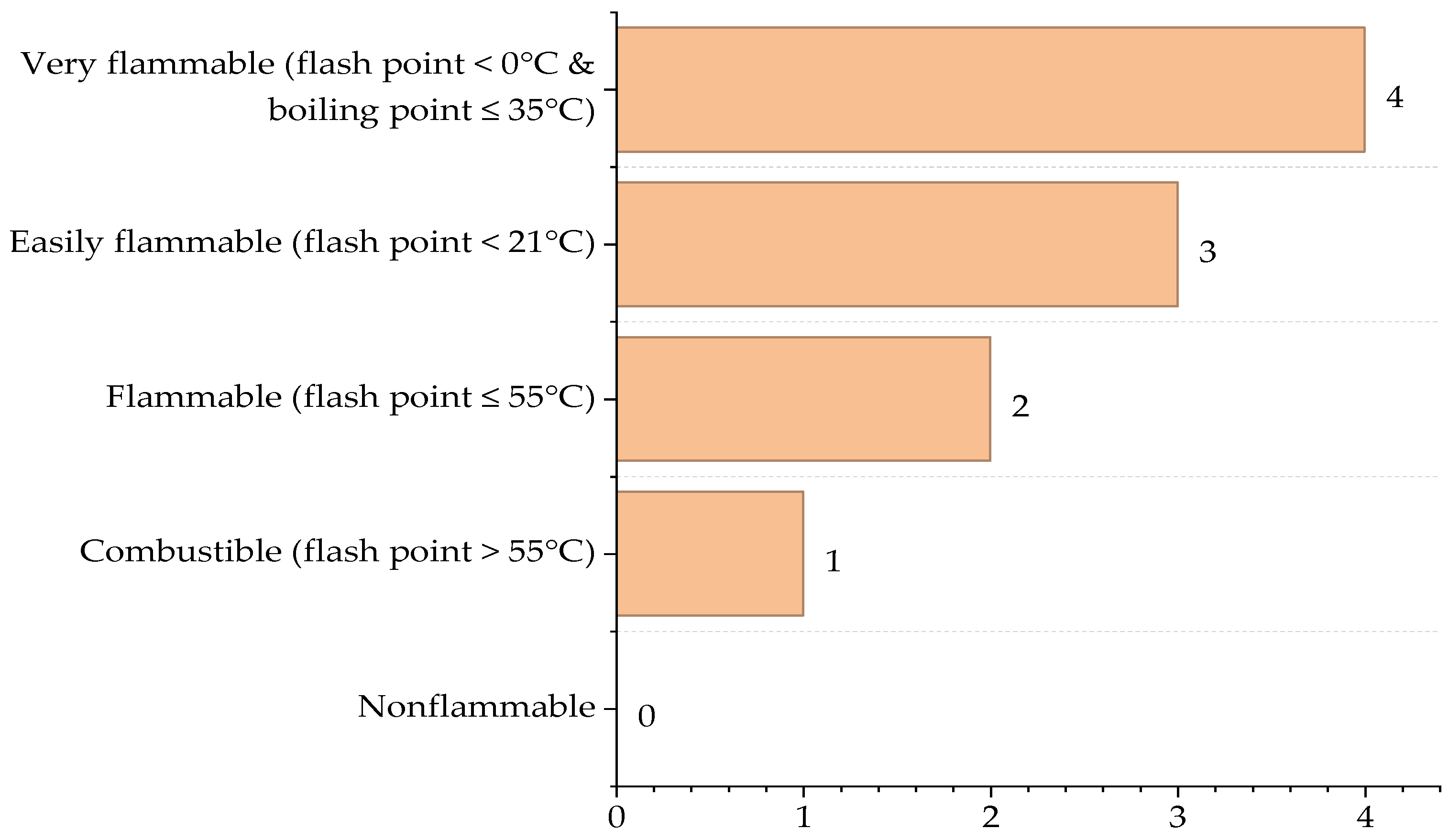

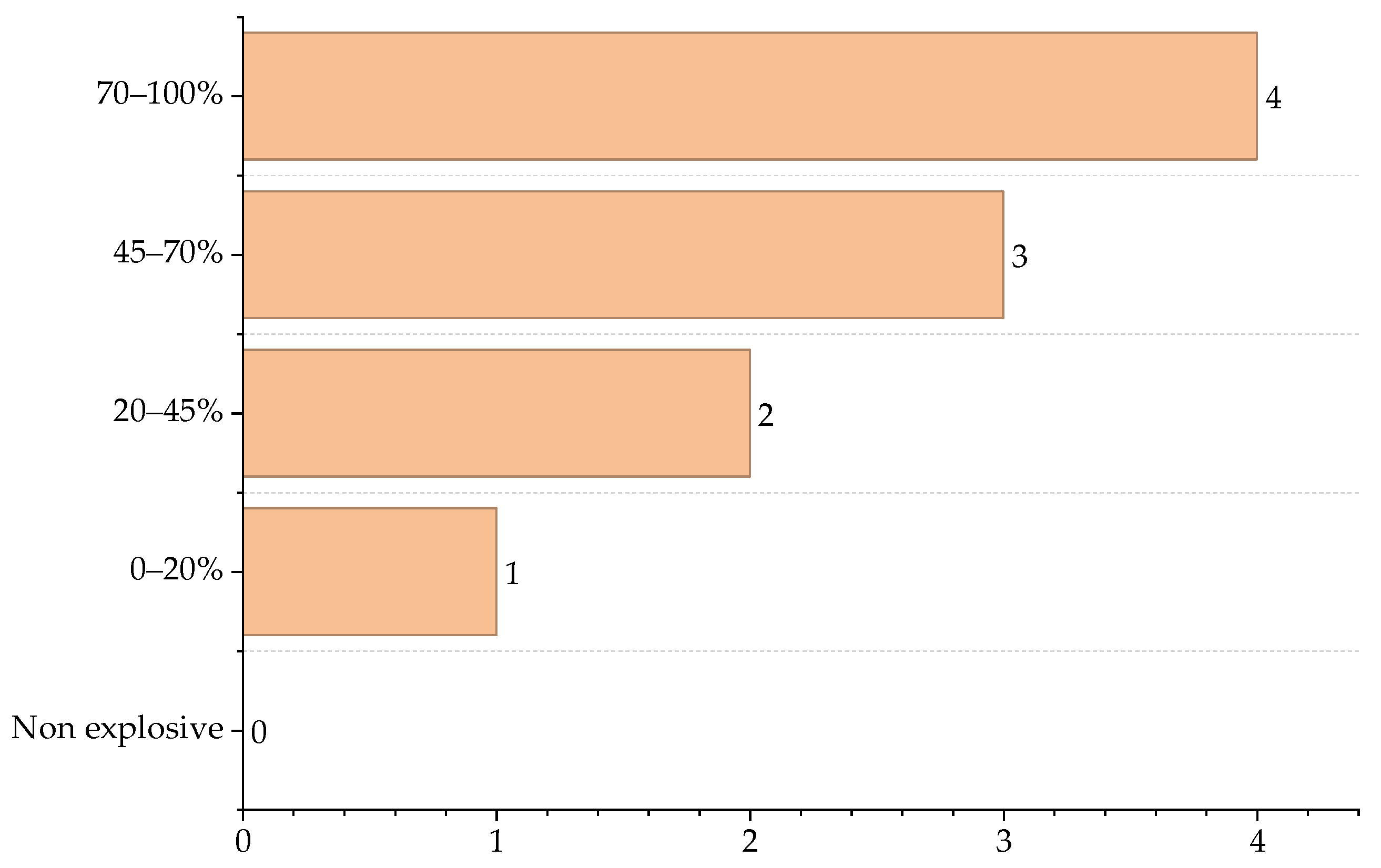

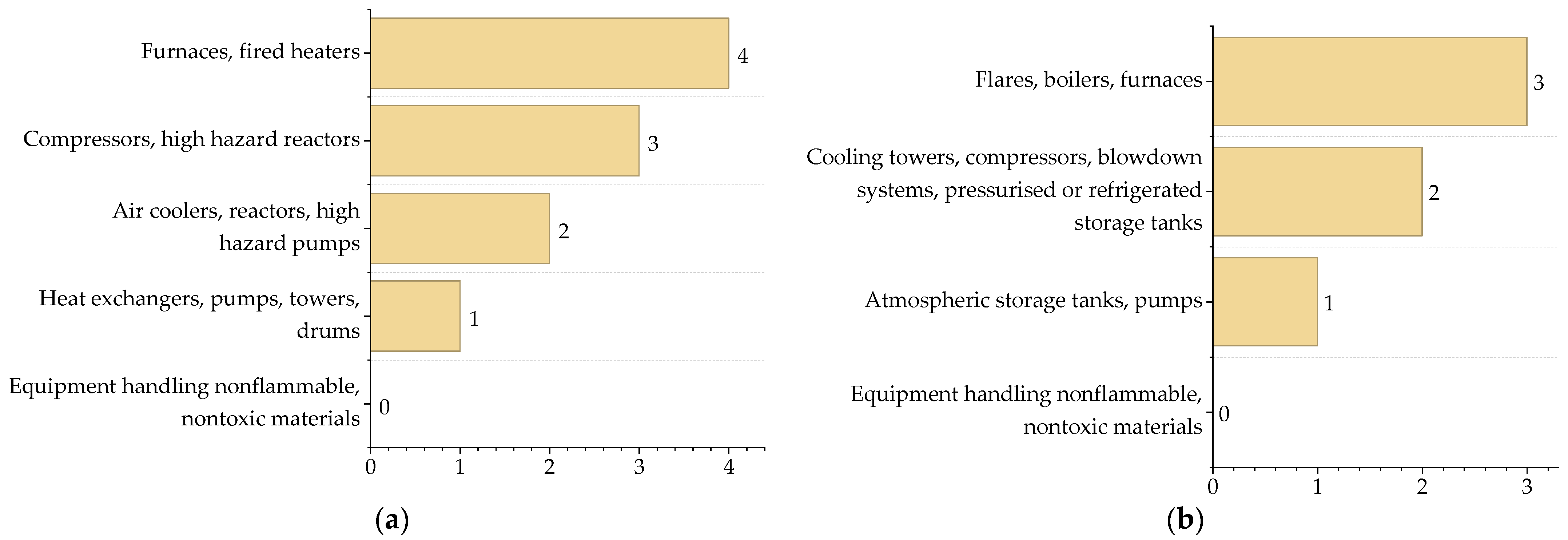

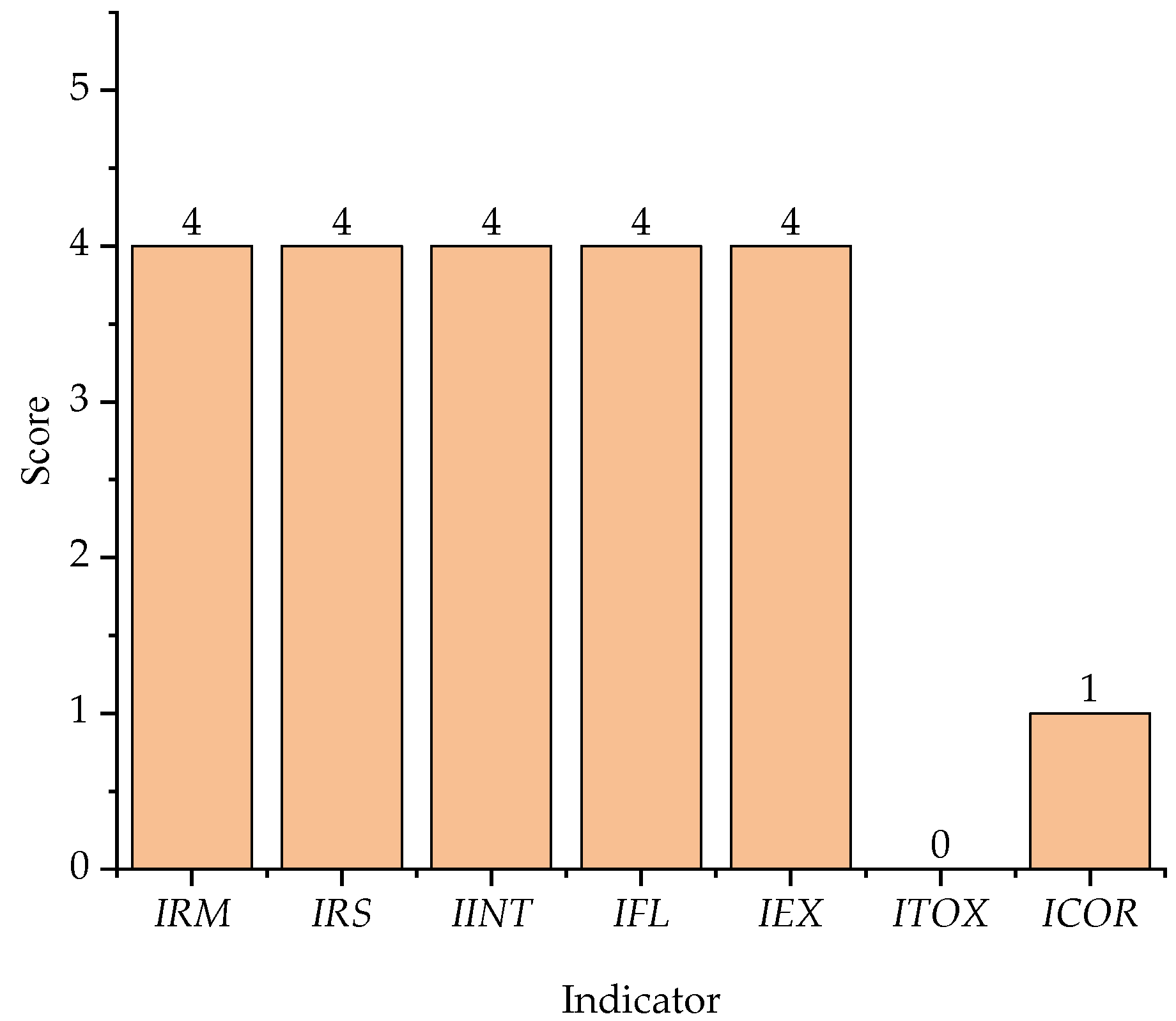

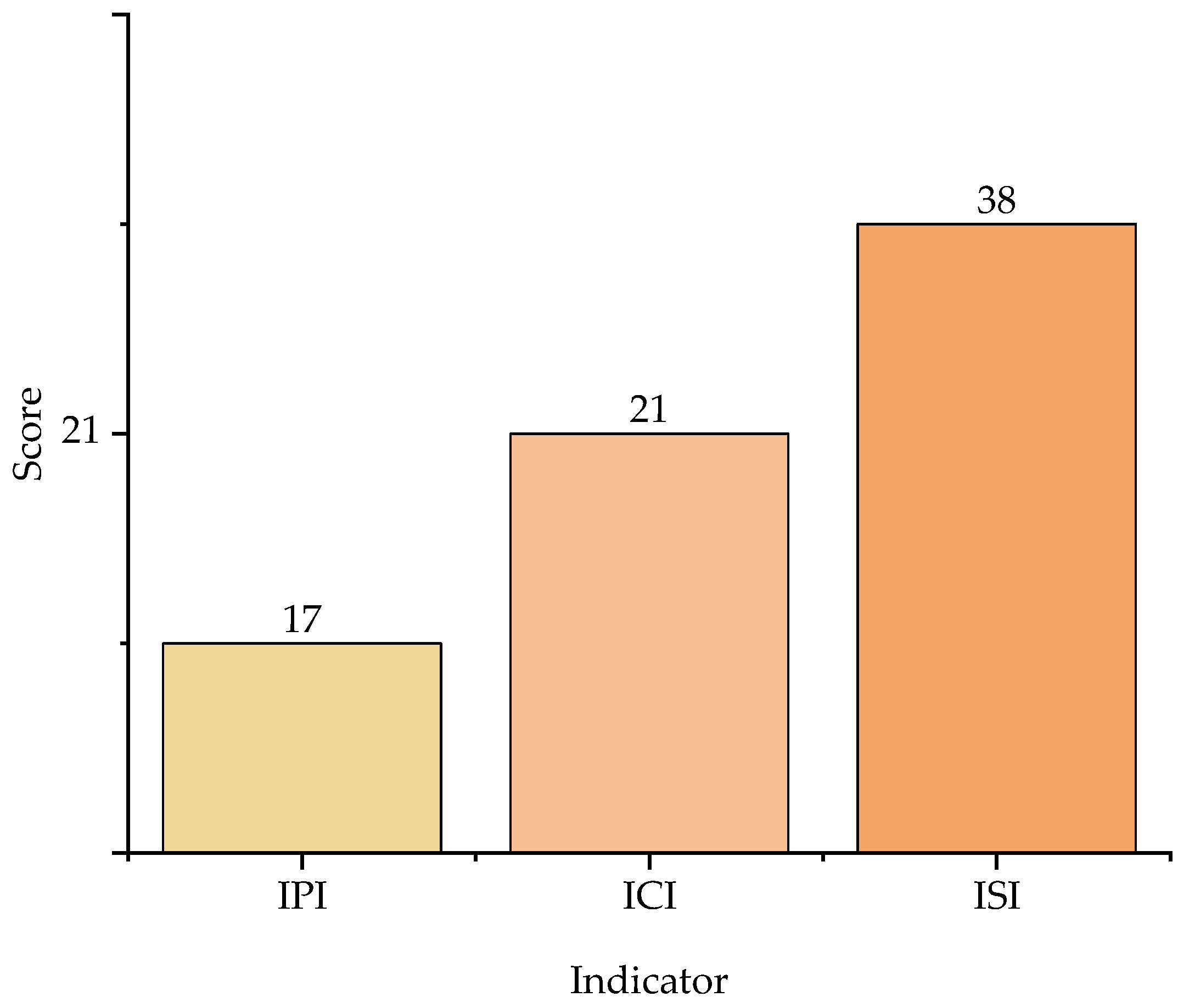

3.1. Contribution of Chemical Process Indicators

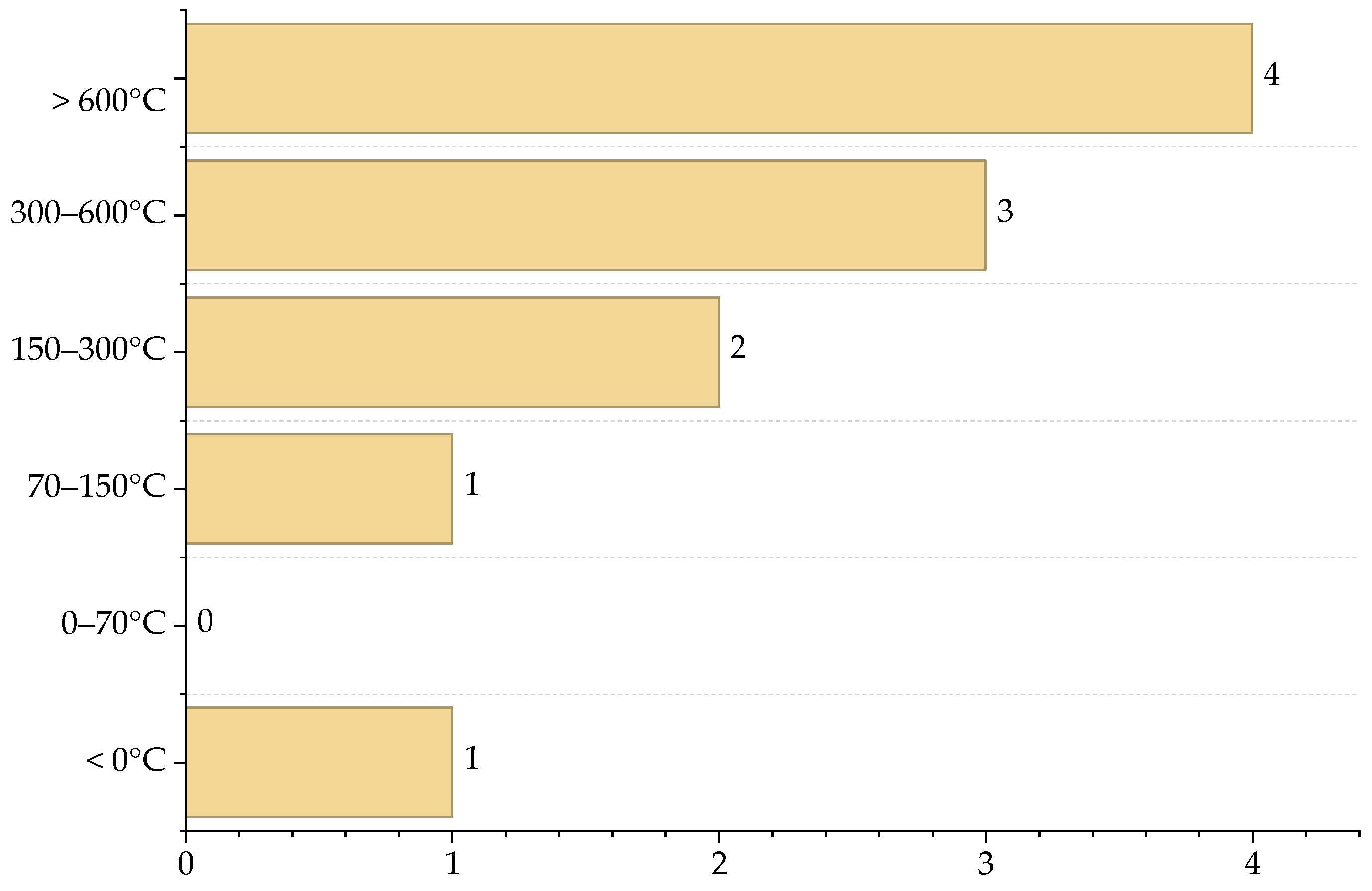

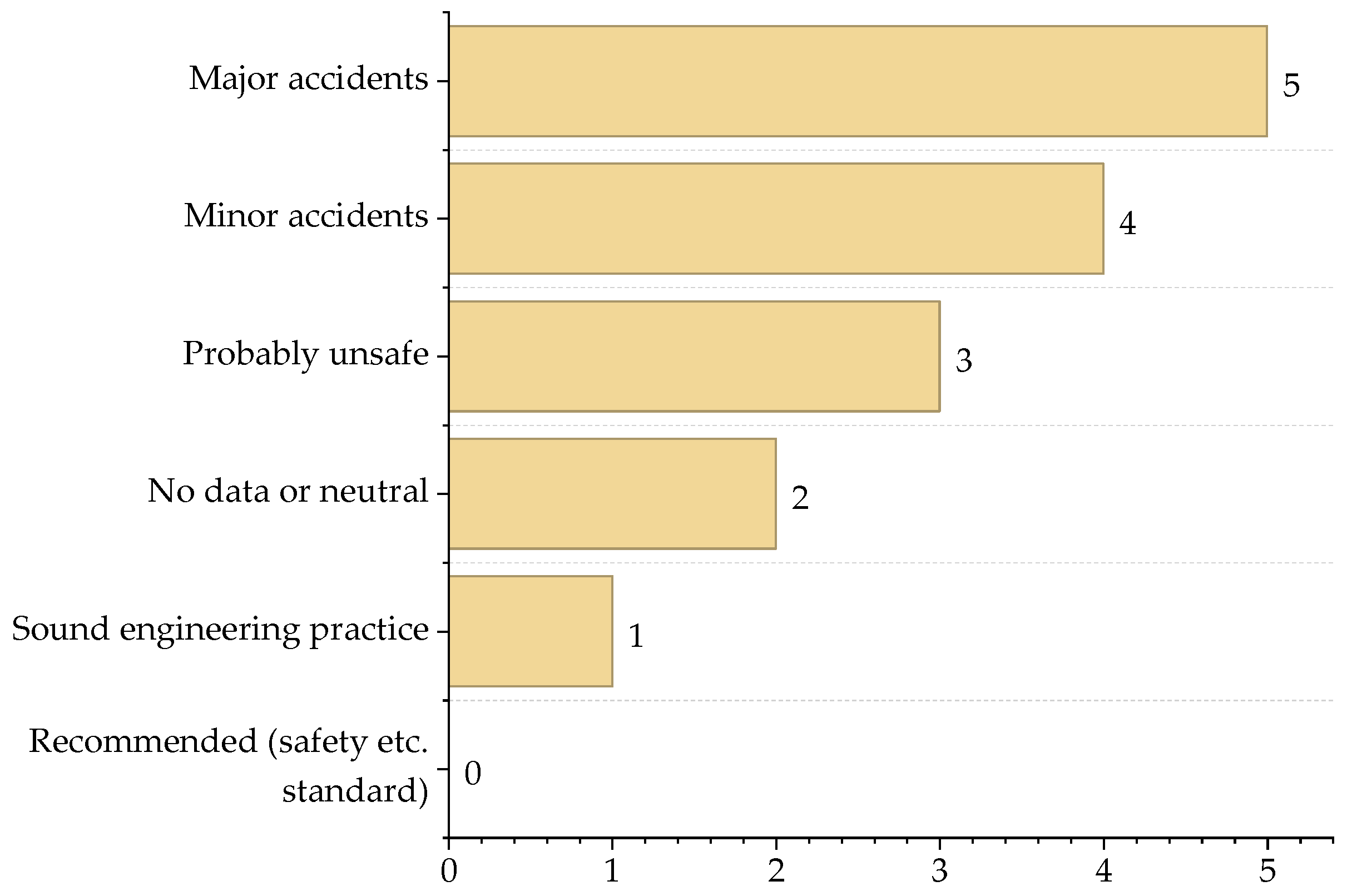

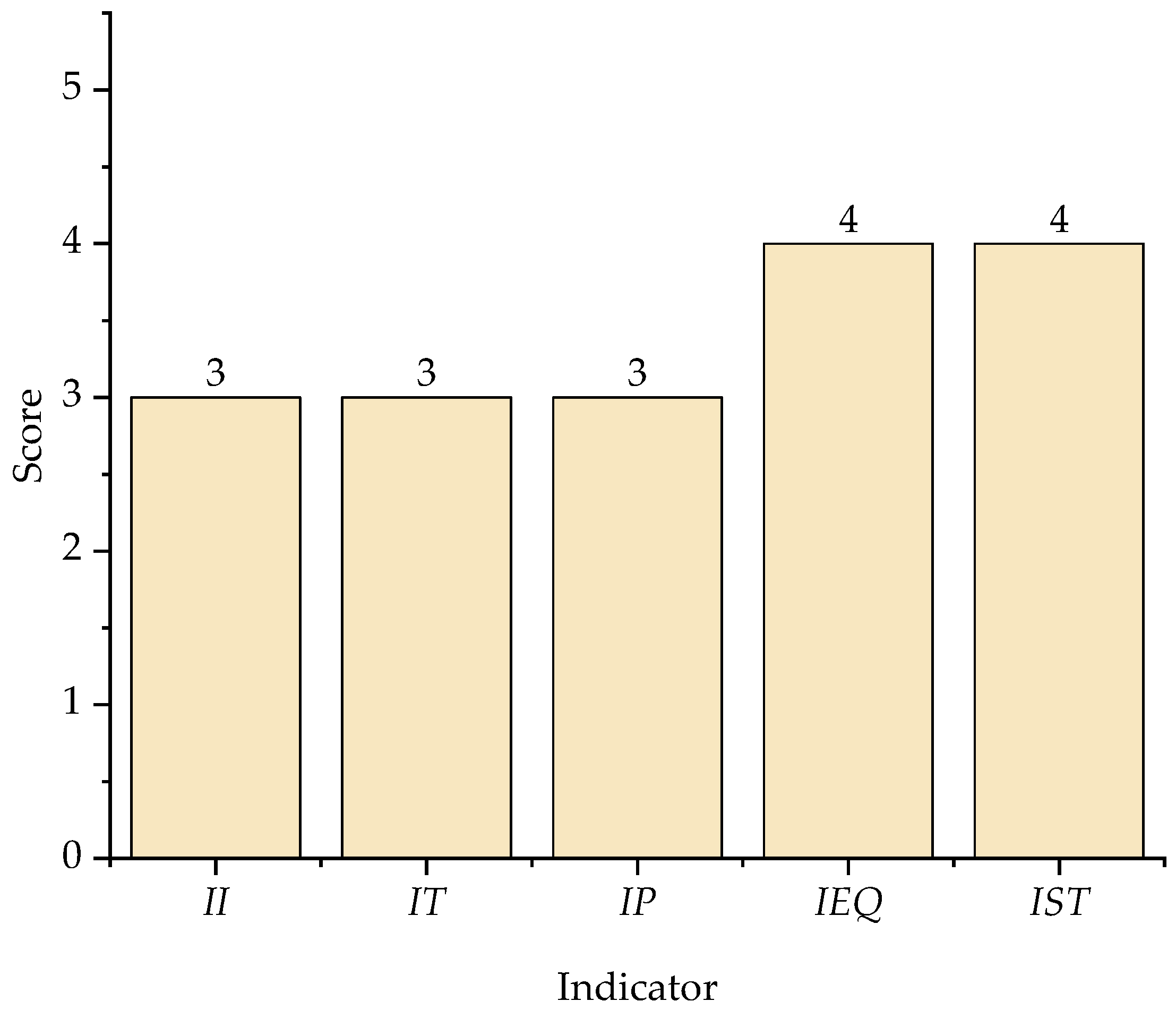

3.2. Contribution of Process Safety Indicator

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISI | Inherent Safety Index |

| ICI | Inherent safety index by chemicals |

| IPI | Inherent Process Safety Index |

| IRM | Main Reaction Heat subindex, J/g |

| IRS | Secondary Reaction Heat Subindex, J/g |

| IINT | Chemical Interactions Subindex |

| IFL | Flammability Subindex, °C |

| IEX | Explosiveness Subindex, % |

| ITOX | Toxicity Subindex, ppm |

| ICOR | Corrosivity Subindex |

| II | Inventory Subindex, t/h |

| IT | Temperature Subindex, °C |

| IP | Pressure Subindex, bar |

| IEQ | Equipment Safety Subindex |

| IST | Safe Structure Level Subindex |

References

- Alvarado-Flores, J.J.; Alcaraz-Vera, J.V.; Ávalos-Rodríguez, M.L.; Guzmán-Mejía, E.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Guevara-Martínez, S.J. Thermochemical Production of Hydrogen from Biomass: Pyrolysis and Gasification. Energies 2024, 17, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Viktor, P.; Al-Musawi, T.J.; Ali, B.M.; Algburi, S.; Alzoubi, H.M.; Al-Jiboory, A.K.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. The renewable energy role in the global energy Transformations. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 48, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnin, A.S.; Wacławiak, K.; Humayun, M.; Zhang, S.; Ullah, H. Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Cobos, L.; Abril-González, M.; Pinos-Vélez, V. Production of Hydrogen from Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Review of Technologies. Catalysts 2023, 13, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Abidin, I.Z.; Mahafzah, K.A.; Hannan, M.A. Feasibility of future transition to 100% renewable energy: Recent progress, policies, challenges, and perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Hashemi, S.J.; Paltrinieri, N.; Amyotte, P.; Cozzani, V.; Reniers, G. Dynamic risk management: A contemporary approach to process safety management. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2016, 14, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehane, A.; Merouani, S.; Chibani, A.; Hamdaoui, O. Clean hydrogen production by ultrasound (sonochemistry): The effect of noble gases. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 5, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, T.; Parejo, V.; González-Delgado, Á. Chemical and Process Inherent Safety Evaluation of Avocado Oil Production (Laurus persea L.) in North Colombia. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 91, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meramo, S.; Gonzalez-Quiroga, A.; Gonzalez-Delgado, A. Technical, Environmental, and Process Safety Assessment of Acetone-Butanol-Ethanol Fermentation of Cassava Residues. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, C.A.B.; Navarro, J.G.G.; Jeisson, G.; Ricaurte, H. Hacia el aprovechamiento energético de los raquis de palma en calderas de biomasa. Palmas 2023, 44, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steff ania López Cuervo, L.; Alberto Ríos, L. Del Raquis de Palma a Combustibles más Limpios. Rev. Exp. 2018, 10, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Segurado, R.; Pereira, S.; Correia, D.; Costa, M. Techno-economic analysis of a trigeneration system based on biomass gasification. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 103, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasman, H.; Sripaul, E.; Khan, F.; Fabiano, B. Energy transition technology comes with new process safety challenges and risks. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 177, 765–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukajtis, R.; Hołowacz, I.; Kucharska, K.; Glinka, M.; Rybarczyk, P.; Przyjazny, A.; Kamiński, M. Hydrogen production from biomass using dark fermentation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, A.-M. Inherent Safety in Process Plant Design: An Index-Based Approach; Technical Research Centre of Finland (VTT): Espoo, Finland, 1999; ISBN 951-38-5371-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kletz, T. Explosions. In Still Going Wrong! Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendershot, D.C. Inherently safer chemical process design. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 1997, 10, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, Á.D.; García-Martínez, J.B.; Barajas-Solano, A.F. Inherent Safety Analysis and Sustainability Evaluation of a Vaccine Production Topology in North-East Colombia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Han, X.; Hao, L.; Wei, H. Development of a general inherent safety assessment tool at early design stage of chemical process. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 167, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Goerlandt, F.; Reniers, G. Trevor Kletz’s scholarly legacy: A co-citation analysis. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2020, 66, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, S.O. Promoting inherent safety. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2010, 88, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunthavanathan, R.; Sajid, Z.; Amin, M.T.; Tian, Y.; Khan, F.; Pistikopoulos, E. Process safety 4.0: Artificial intelligence or intelligence augmentation for safer process operation? AIChE J. 2024, 70, e18475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kang, D. Artificial Intelligence and Smart Technologies in Safety Management: A Comprehensive Analysis Across Multiple Industries. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Mira, A.; Zuluaga-García, C.; González-Delgado, Á.D. A Technical and Environmental Evaluation of Six Routes for Industrial Hydrogen Production from Empty Palm Fruit Bunches. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 15457–15470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durán-García, M.E.; Ruiz-Navas, R.A. Simulador de propiedades termodinámicas en la conversión de la biomasa forestal de aserrín de pino. Maderas-Cienc Tecnol 2020, 22, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.; Salmiaton, A.; Azlina, W.W.; Amran, M.M. Gasification of Empty Fruit Bunch for Hydrogen Rich Fuel Gas Production. J. Appl. Sci. 2011, 11, 2416–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aholoukpè, H.; Dubos, B.; Flori, A.; Deleporte, P.; Amadji, G.; Chotte, J.L.; Blavet, D. Estimating aboveground biomass of oil palm: Allometric equations for estimating frond biomass. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 292, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.; Salmiaton, A.; Azlina, W.W.; Amran, M.M. Gasification of oil palm empty fruit bunches: A characterization and kinetic study. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, A.D.; Pájaro-Gómez, N.; Ortega-Toro, R. Inherent safety analysis and sustainability evaluation of dual crude palm and kernel oil production in North Colombia. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quim. 2023, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kletz, T.A. Inherently safer design: The growth of an idea. Process Saf. Prog. 1996, 15, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kletz, T.A. Inherently safer plants. Plant/Oper. Prog. 1985, 4, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendivil-Arrieta, A.; Diaz-Pérez, J.M.; González-Delgado, Á.D. Effect of Energy Integration on Safety Indexes of Suspension PVC Production Process. Processes 2025, 13, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, A.; Mannan, S.; Cagin, T. Molecular-Level Modeling and Simulation in Process Safety. In Multiscale Modeling for Process Safety Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 111–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.L.; Williams, F.A. Recent advances in understanding of flammability characteristics of hydrogen. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2014, 41, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-Q.; Sun, Z.-Y. Experimental studies on explosive limits and minimum ignition energy of syngas: A comparative review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 5640–5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Chen, D.; Zi, M.; Wu, G. Effects of carbon steel corrosion on the methane hydrate formation and dissociation. Fuel 2018, 230, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veysi, A.; Roushani, M.; Najafi, H. Synthesis and evaluation of CuNi-MOF as a corrosion inhibitor of AISI 304 and 316 stainless steel in 1N HCl solution. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, M.; Portarapillo, M.; Di Nardo, A.; Venezia, V.; Turco, M.; Luciani, G.; Di Benedetto, A. Hydrogen Safety Challenges: A Comprehensive Review on Production, Storage, Transport, Utilization, and CFD-Based Consequence and Risk Assessment. Energies 2024, 17, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.X.; Marono, M.; Moretto, P.; Reinecke, E.-A.; Sathiah, P.; Studer, E.; Vyazmina, E.; Melideo, D. Statistics, lessons learned and recommendations from analysis of HIAD 2.0 database. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 17082–17096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Su, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, J.; Guan, X.; Cao, W.; Ou, Z. Hydrogen safety: An obstacle that must be overcome on the road towards future hydrogen economy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 1055–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, A.D.; Barajas-Solano, A.F.; Leon-Pulido, J. Evaluating the Sustainability and Inherent Safety of a Crude Palm Oil Production Process in North-Colombia. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, A.D.; García-Martínez, J.B.; Barajas-Solano, A.F. Evaluation of Algae-Based Biodiesel Production Topologies via Inherent Safety Index (ISI). Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zanwar, A.; Jayswal, A.; Lou, H.H.; Huang, Y. Incorporating Exergy Analysis and Inherent Safety Analysis for Sustainability Assessment of Biofuels. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 2981–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balat, M.; Balat, H. Progress in biodiesel processing. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 1815–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.; Wu, X.; Leung, M. A review on biodiesel production using catalyzed transesterification. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D.C.; Biller, P.; Ross, A.B.; Schmidt, A.J.; Jones, S.B. Hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass: Developments from batch to continuous process. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 178, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Jones, D.D.; Hanna, M.A. Thermochemical Biomass Gasification: A Review of the Current Status of the Technology. Energies 2009, 2, 556–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhul, A.M.; Kalam, M.A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Reham, S.S.; Rashed, M.M. State of the art of biodiesel production processes: A review of the heterogeneous catalyst. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 101023–101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Hazelnut Shell to Hydrogen-Rich Gaseous Products via Catalytic Gasification Process. Energy Sources 2004, 26, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarian, S.; Unnþórsson, R.; Richter, C. A review of biomass gasification modelling. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 110, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Henriksen, U.B.; Ciolkosz, D. Startup process, safety and risk assessment of biomass gasification for off-grid rural electrification. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, G.; Kaewpanha, M.; Hao, X.; Abudula, A. Catalytic steam reforming of biomass tar: Prospects and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 58, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Xu, Z.; Qi, H.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Cui, P. Carbon footprint and water footprint analysis of generating synthetic natural gas from biomass. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoît, C.; Norris, G.A.; Valdivia, S.; Ciroth, A.; Moberg, A.; Bos, U.; Prakash, S.; Ugaya, C.; Beck, T. The guidelines for social life cycle assessment of products: Just in time! Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiderio, E.; Östergren, K. Beyond the fields: Unravelling the social consequences of green pea protein production from a Swedish perspective. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2025, 19, 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reactor Type | Main Reaction | ∆Hr (J/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Gasifier | CH4 + 2O2 → CO2 + 2H2O C + CO2 → 2CO C + 2H2 → CH4 S + O2 → SO2 C + O2 → CO2 | −31,148.5 1049.3 −4680.0 −4639.7 −8947.3 |

| Gasifier, HTS, and LTS | CO + H2O → H2 + CO2 | 8442.2 |

| Reactor Type | Second Reaction | ∆Hr (J/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Gasifier | 730.9 −5729.3 −14,171.5 | |

| Gasifier and HTS | 14,171.5 |

| Substance | Type of Interaction | Score ICI |

|---|---|---|

| CO | Formation of flammable gas1 | 2 |

| H2O | Does not interact | 0 |

| O2 | Does not interact | 0 |

| H2 | Explosion | 4 |

| CH4 | Explosion | 4 |

| SO2 | Does not interact | 0 |

| CO2 | Does not interact | 0 |

| N2 | Does not interact | 0 |

| Selexol | Soluble toxic chemicals | 1 |

| S | Explosion | 4 |

| Maximum score | 4 | |

| Substance | Flash Point (°C)/Boiling Point (°C) | Flammability Type | Score ICI |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO | Formation of flammable gas1 | Non-flammable | 0 |

| H2O | Does not interact | Non-flammable | 0 |

| O2 | Does not interact | Non-flammable | 0 |

| H2 | Explosion | Very flammable | 4 |

| CH4 | Explosion | Very flammable | 4 |

| SO2 | Does not interact | Non-flammable | 0 |

| CO2 | Does not interact | Non-flammable | 0 |

| N2 | Does not interact | Non-flammable | 0 |

| Selexol | Soluble toxic chemicals | Fuel | 1 |

| S | Explosion | Fuel | 1 |

| Maximum score | 4 | ||

| Substance | (UEL-LEL) % | Score ICI |

|---|---|---|

| CO | 63.00 | 4 |

| H2O | Non-explosive | 0 |

| O2 | Non-explosive | 0 |

| H2 | 71.00 | 4 |

| CH4 | 10.00 | 1 |

| SO2 | Non-explosive | 0 |

| CO2 | Non-explosive | 0 |

| N2 | Non-explosive | 0 |

| Selexol | 0.80 | 1 |

| S | - | - |

| Maximum score | 4 | |

| Substance | TLV (ppm) | Score ICI |

|---|---|---|

| CO | 3760.00 | 1 |

| H2O | Non-toxic | 0 |

| O2 | Non-toxic | 0 |

| H2 | Non-toxic | 0 |

| CH4 | Non-toxic | 0 |

| SO2 | 0.25 | 5 |

| CO2 | 5000.00 | 1 |

| N2 | Non-toxic | 0 |

| Selexol | - | - |

| S | 1.00 | 5 |

| Maximum score | 5 | |

| Indicator | Conventional Transesterification (Biodiesel) | In Situ Transesterification (Biodiesel) | Hydrothermal Liquefaction (Biodiesel) | Heterogeneous Catalyst Process (Biodiesel) | Hydrogen (H2) by Direct Gasification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRM | 4 | 4 | 4 | - | 4 |

| IRS | 4 | 4 | 4 | - | 4 |

| IINT | 4 | 4 | 4 | - | 4 |

| IFL | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| IEX | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| ITOX | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| ICOR | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| II | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| IT | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| IP | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| IEQ | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| IST | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| ISI | 30 | 29 | 36 | 16 | 38 |

| Reference | [42] | [42] | [42] | [43] | This Work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mejía-González, L.; Mendivil-Arrieta, A.; González-Delgado, Á.D. Analysis of Inherent Chemical and Process Safety for Biohydrogen Production from African Palm Rachis via Direct Gasification and Selexol Purification. Processes 2025, 13, 4052. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124052

Mejía-González L, Mendivil-Arrieta A, González-Delgado ÁD. Analysis of Inherent Chemical and Process Safety for Biohydrogen Production from African Palm Rachis via Direct Gasification and Selexol Purification. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4052. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124052

Chicago/Turabian StyleMejía-González, Lina, Antonio Mendivil-Arrieta, and Ángel Darío González-Delgado. 2025. "Analysis of Inherent Chemical and Process Safety for Biohydrogen Production from African Palm Rachis via Direct Gasification and Selexol Purification" Processes 13, no. 12: 4052. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124052

APA StyleMejía-González, L., Mendivil-Arrieta, A., & González-Delgado, Á. D. (2025). Analysis of Inherent Chemical and Process Safety for Biohydrogen Production from African Palm Rachis via Direct Gasification and Selexol Purification. Processes, 13(12), 4052. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124052