1. Introduction

Distribution systems serve as a critical link in the power system infrastructure, responsible for delivering electrical energy from high-voltage transmission systems to end-use consumers. In recent years, the widespread deployment of Distributed Generation (DG) units, electric vehicles, energy storage systems, and advanced demand-side management technologies has fundamentally transformed the operational landscape of the distribution systems [

1]. This evolution has introduced new operational challenges, characterized by high renewable energy penetration, bidirectional power flows, and pronounced load variability. Concurrently, legacy distribution system infrastructure continues to suffer from aging equipment, sparse sensor deployment, and suboptimal operational control strategies [

2], thereby imposing stringent requirements on system safety, reliability, and economic efficiency.

State estimation constitutes a foundational capability for the real-time monitoring and control of distribution systems. By continuously processing streaming measurement data, state estimators provide accurate estimates of critical operational variables, including nodal voltages, branch power flows, and nodal power injections. These estimates enable enhanced situational awareness, accelerated fault detection and localization, optimized dispatch decisions, and maximized renewable energy integration [

3]. Consequently, developing robust and efficient state estimation techniques is essential for realizing intelligent and adaptive distribution system management.

State estimation methods can be categorized into model-driven and data-driven approaches based on their underlying modeling strategies. The Weighted Least Squares (WLS) method, a widely used model-driven approach, formulates state estimation as a weighted least-squares optimization problem to minimize the sum of squared weighted measurement residuals [

4,

5]. However, WLS exhibits poor robustness when dealing with noisy measurements or outliers, demonstrates strong dependency on network observability, and frequently encounters convergence difficulties [

6]. Although several variants incorporating robust estimation techniques [

7] or bad data detection mechanisms [

8] have been proposed, these approaches remain computationally expensive and suffer from slow convergence, thereby limiting their applicability to real-time operations.

Data-driven approaches overcome these limitations by offering superior feature extraction capabilities and computational efficiency, making them particularly well-suited for complex distribution systems characterized by incomplete measurement coverage. Representative works include: Ref. [

9], which employs spiking neural networks to synthesize pseudo-measurements for three-phase state estimation; Ref. [

10], which proposes a correlation-aware weight initialization strategy to accelerate training convergence in large-scale systems; and Ref. [

11], which leverages a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) within a Bayesian framework to characterize the probabilistic distribution of load power and predict conditional expectations of state variables. Extending this line of research, Ref. [

12] incorporates the residuals of power flow equations into the loss function, significantly improving the accuracy of state estimation.

GNNs have recently emerged as a promising paradigm for modeling non-Euclidean network structures, including power systems [

13,

14]. Ref. [

15] utilizes message-passing mechanisms to facilitate information propagation among neighboring nodes, effectively capturing topology-dependent state relationships. Ref. [

16] augments the Graph Attention Network (GAT) framework with global multi-head attention modules to enhance robustness to measurement noise. Additionally, Ref. [

17] investigates weakly supervised GNN-based learning by integrating physical priors, thereby reducing the reliance on high-quality labeled data. Despite their strong real-time performance, existing data-driven state estimation methods typically overlook the physical constraints inherent in distribution systems, leading to reduced accuracy and limited generalization under sparse measurement conditions.

To address the challenges imposed by sparse measurements and frequent topological changes in distribution systems, this study proposes a physics-constrained GNN approach for distribution system state estimation (DSSE). Firstly, a GMM-based probabilistic data augmentation strategy is introduced to model the stochastic behavior of loads and DG, enabling the generation of realistic synthetic samples under data-scarce scenarios. Secondly, a GAT-based spatial feature learning module with topological feature embedding is designed to effectively capture spatial dependencies and structural correlations among nodes. Finally, a physics-constrained regularization mechanism is developed by incorporating operational limits on nodal power and voltage magnitudes into the loss function, ensuring physical consistency throughout model training. Extensive experiments conducted on the real-world 141-bus system verify that the proposed approach outperforms existing data-driven methods in terms of estimation accuracy, robustness, and generalization ability.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

We develop a GMM-based probabilistic data augmentation framework that explicitly models the stochastic variability of loads and distributed generation units.This strategy not only generates realistic synthetic samples to mitigate data scarcity during training but also covers corner cases arising from loads and DG volatility, thereby ensuring model robustness against the high stochasticity inherent in modern distribution networks.

We construct a GAT learning module with topology-aware admittance matrix embedding to capture fine-grained spatial correlations and structural coupling inherent in distribution systems.

We propose a physics-constrained loss regularization strategy that incorporates nodal power and voltage inequality constraints, ensuring physical feasibility and significantly enhancing estimation accuracy and robustness in low-observability conditions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a comprehensive review of existing state estimation methods for distribution systems, including both non-graph-based and graph-based approaches.

Section 3 introduces the methodology of GMM-based data augmentation and the proposed physics-constrained GAT-based state estimation model.

Section 4 details the experimental validation, including effectiveness analysis and robustness analysis across multiple test scenarios. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of key findings.

5. Conclusions

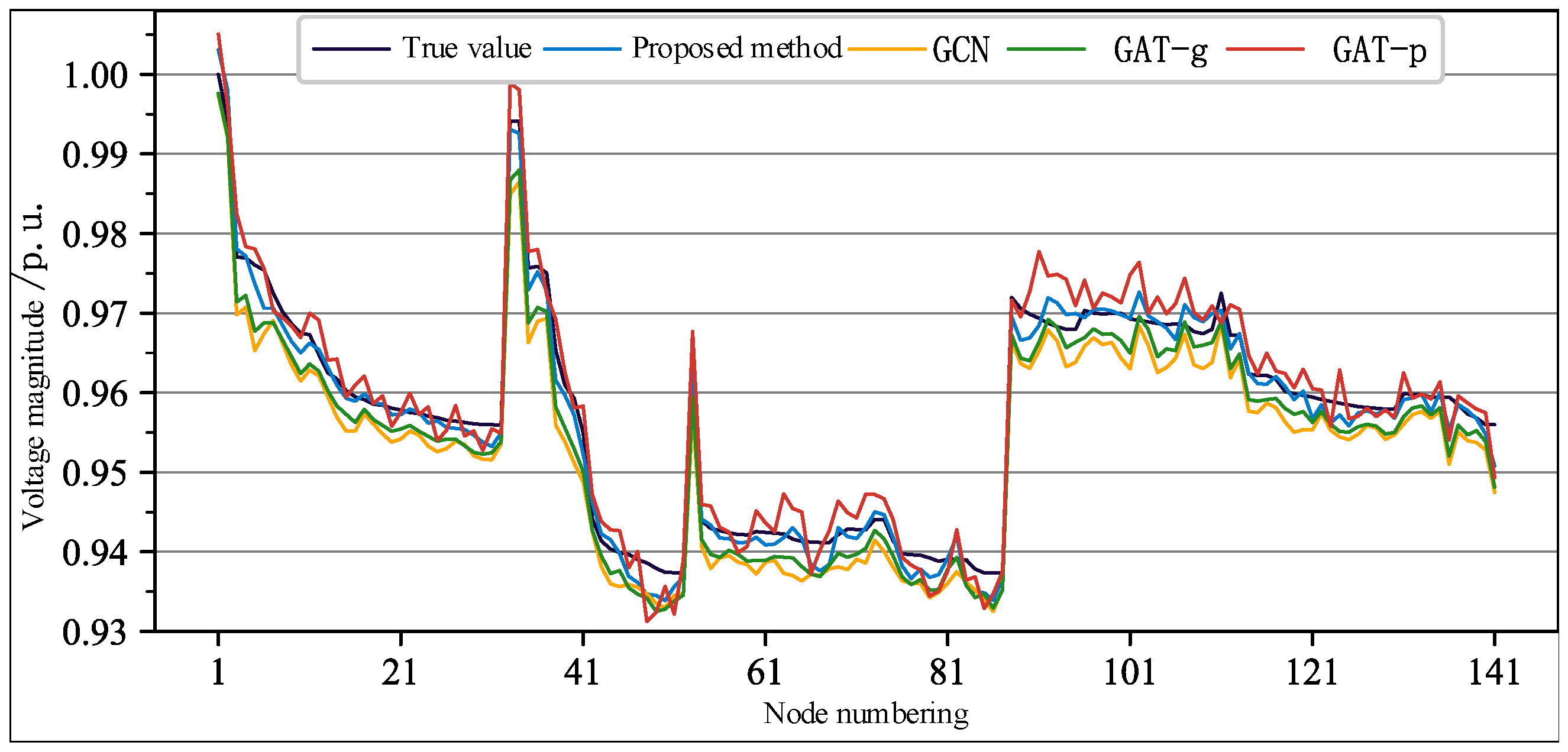

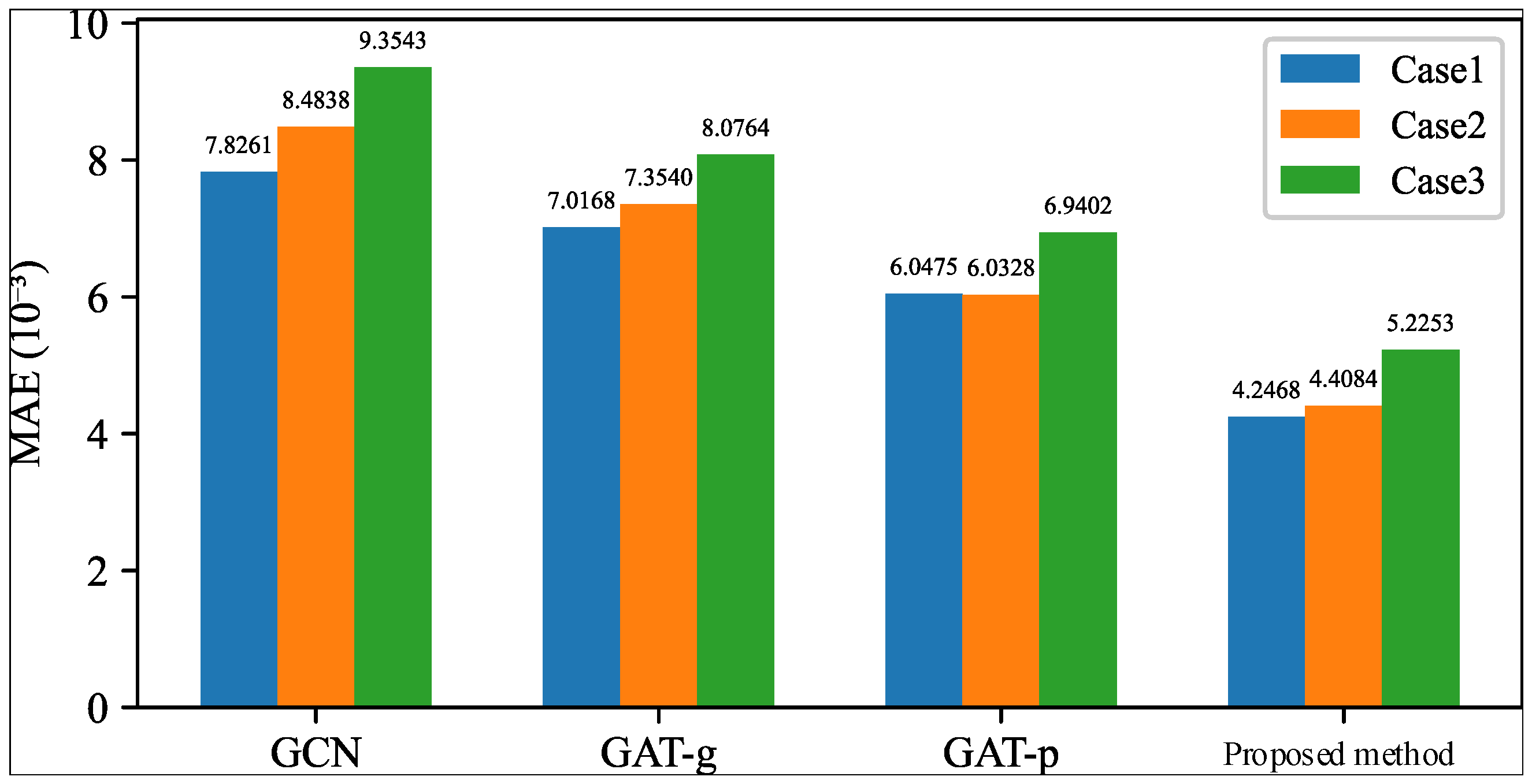

To address the challenges of insufficient training data and inadequate utilization of physical information in existing data-driven state estimation methods, this paper proposes a novel distribution system state estimation approach that integrates physical constraints with a GAT. The method targets scenarios with limited deployment of real-time measurement devices across nodes. First, a GMM-based data augmentation technique is developed to expand the training dataset by learning the probabilistic distribution of nodal power injections and generating synthetic samples. Second, a GAT-based node feature learning module is designed to effectively capture the mapping between measurement information and system states. Furthermore, a topology feature embedding module is introduced to extract and regulate node features using the network admittance matrix. In addition, an operational constraint embedding module is incorporated into the loss function, adding penalties for power flow and voltage limit violations to guide model optimization in a physically consistent manner. The proposed method is validated on the real-world 141-bus test system. Experimental results demonstrate that, compared with data-driven baselines such as GCN, the proposed method achieves a 13.1–52.4% reduction in voltage magnitude MAE and a 16.3–45.5% reduction in voltage phase angle MAE. Moreover, by jointly training with datasets of multiple network topologies, the model maintains consistent estimation performance under various structural configurations, enabling adaptability to dynamic grid topology changes. Additionally, the proposed method exhibits robustness against data quality issues, sustaining stable estimation accuracy in scenarios with missing measurements and noisy data, which confirms its effectiveness and reliability in practical distribution system environments.

Despite the promising results, this study is subject to certain limitations. First, the proposed framework has been validated primarily on simulated datasets derived from standard test systems, while its performance on large-scale, real-world distribution networks remains to be further verified. Second, although the model exhibits a degree of robustness against measurement noise, the impact of extreme scenarios, such as bad data and false data injection attacks, has not been explicitly considered. Future work will focus on addressing these challenges to enhance the practical applicability of the proposed method.