Controls of Fault System on Hydrocarbon Accumulation: A Case Study from the Carboniferous Reservoir of the Hongche Fault Zone in the Junggar Basin

Abstract

1. Introduction

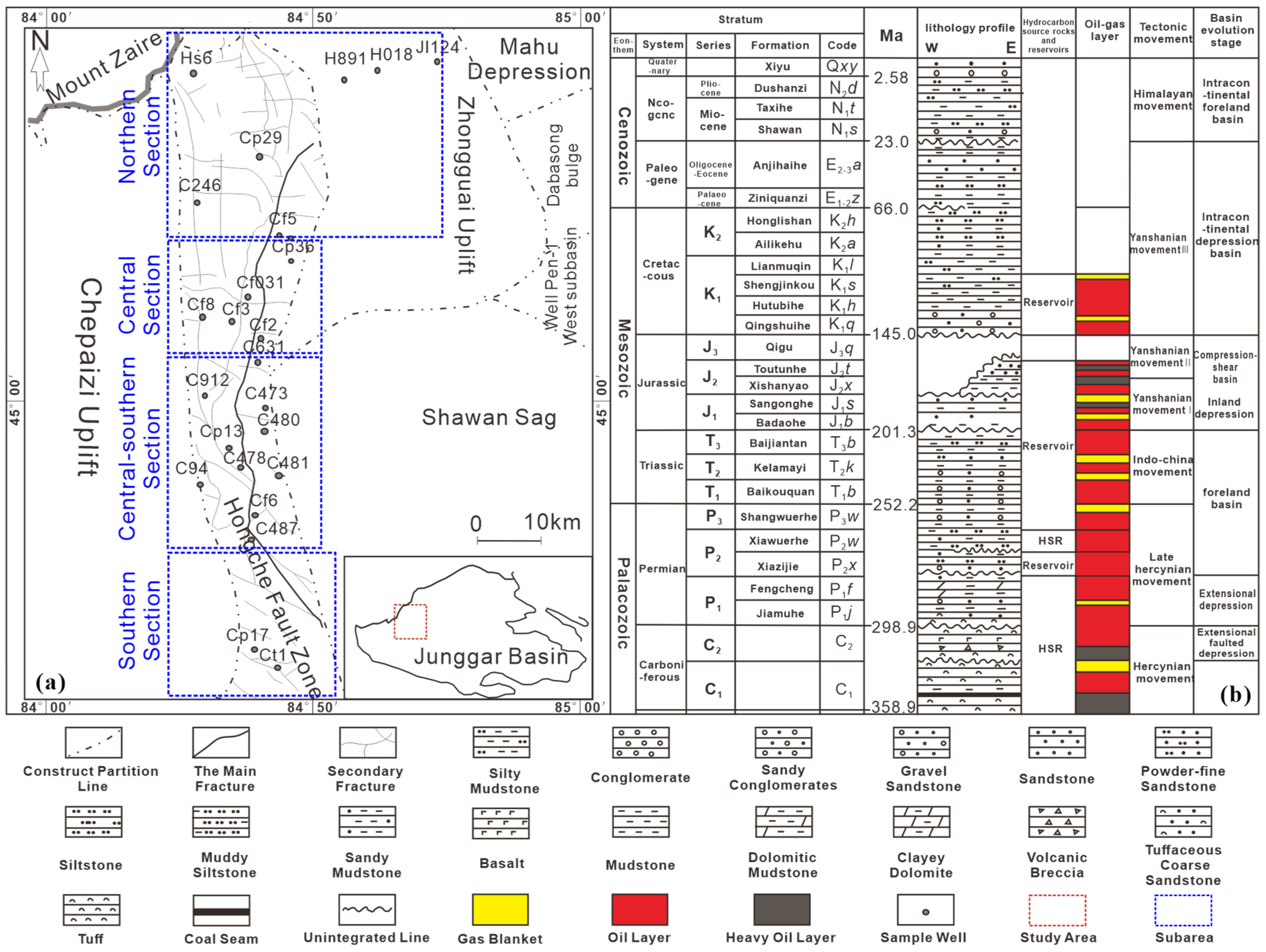

Geological Setting

2. Tectonic Characteristics

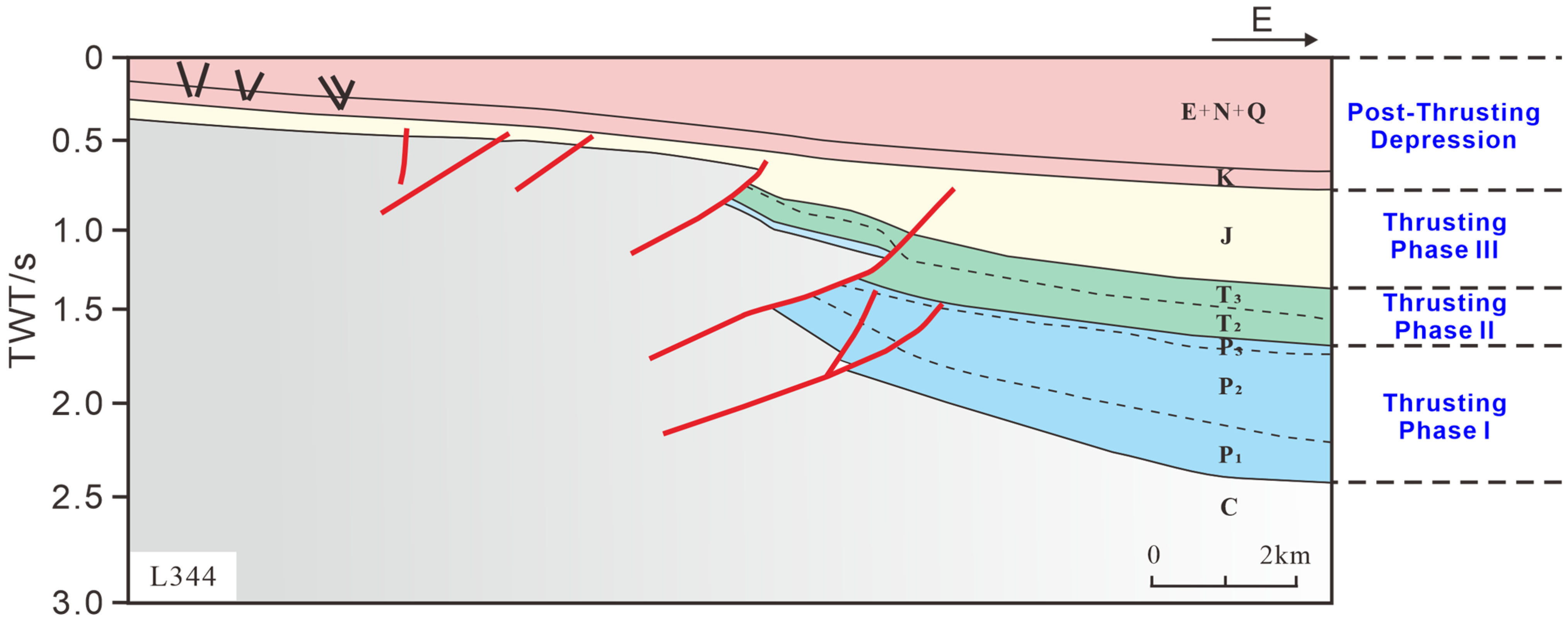

2.1. Construction Layer and Indentation Structure

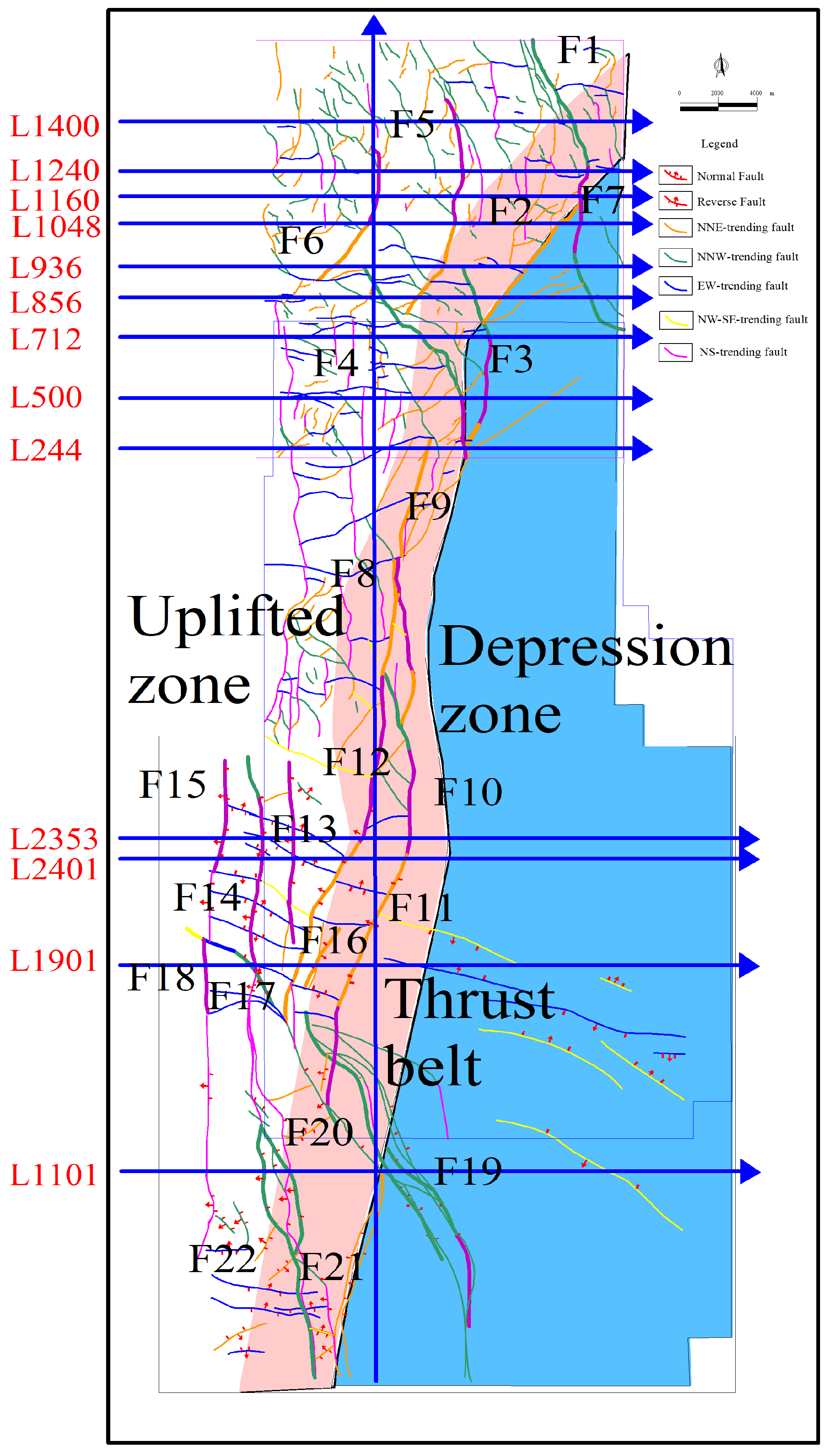

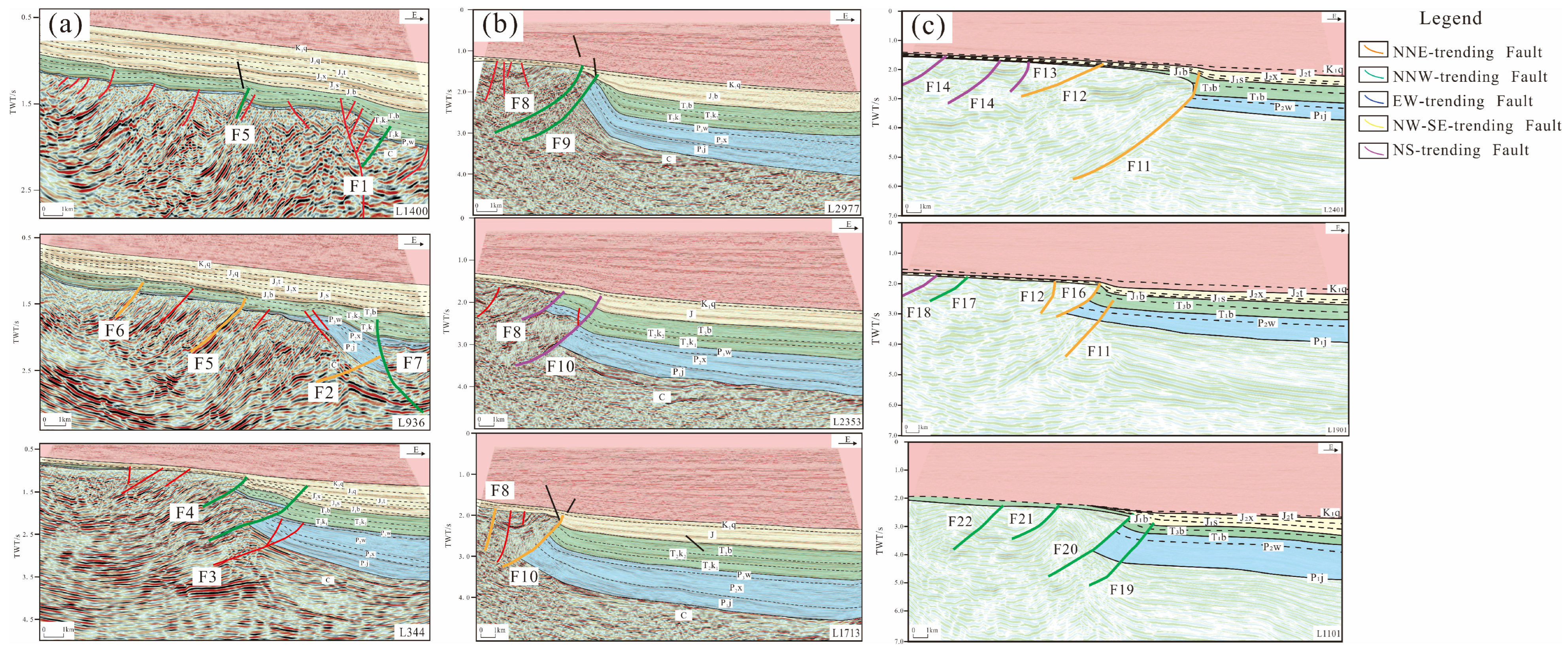

2.2. Structural Style and Planar Distribution

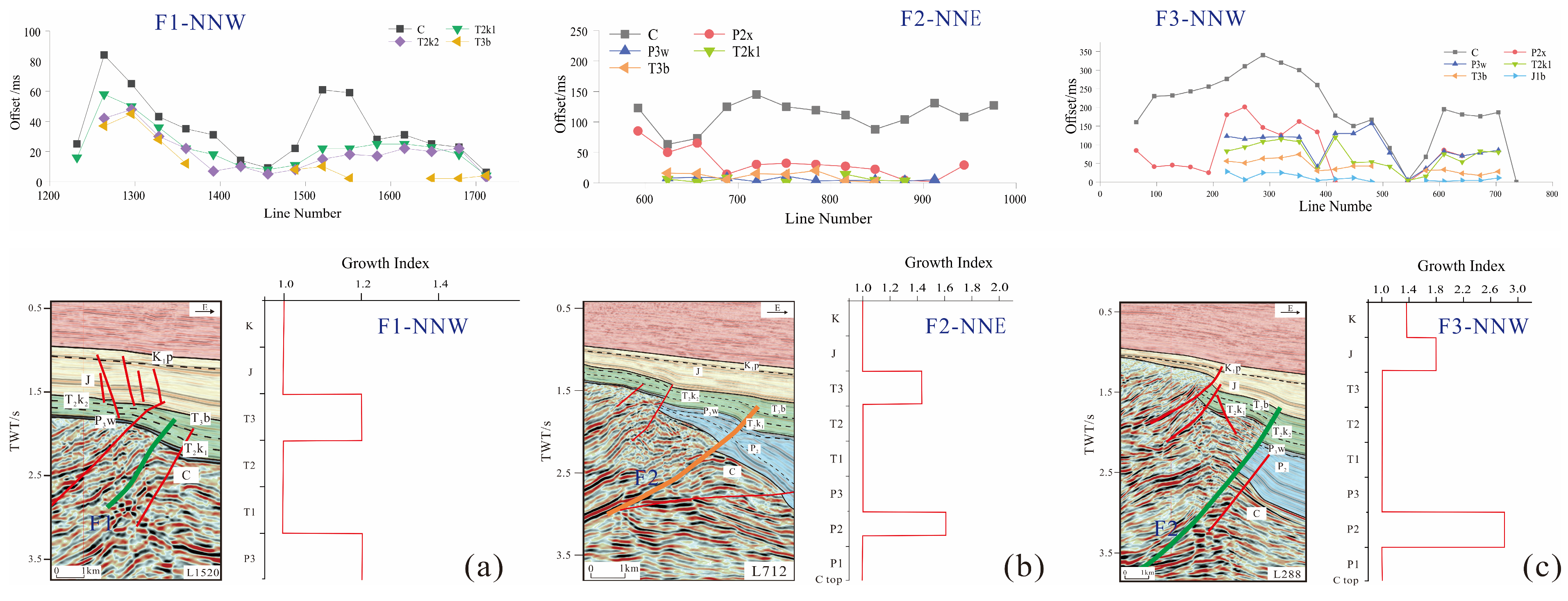

2.3. Classification of Fracture Systems

- Basal “Broad, Low-Amplitude Uplift” (Fault Initiation Stage, Permian)

- 2.

- High-Amplitude “Sharp Main Peak” (Main Fault Activity Stage, Triassic)

- 3.

- “Secondary Peak” on F2 and F3 Curves (Sustained Fault Activity Stage, Jurassic)

- 4.

- Curve Flattening (Fault Inactivity Stage, Cretaceous–Cenozoic)

2.4. Conductivity Characteristics of Fault Systems

- Timing Matching Determines the Effectiveness of Oil–Source Faults

- 2.

- Fault Geometry Controls Reservoir Fracture Network and Permeability

3. Hydrocarbon Source and Charging Pathways

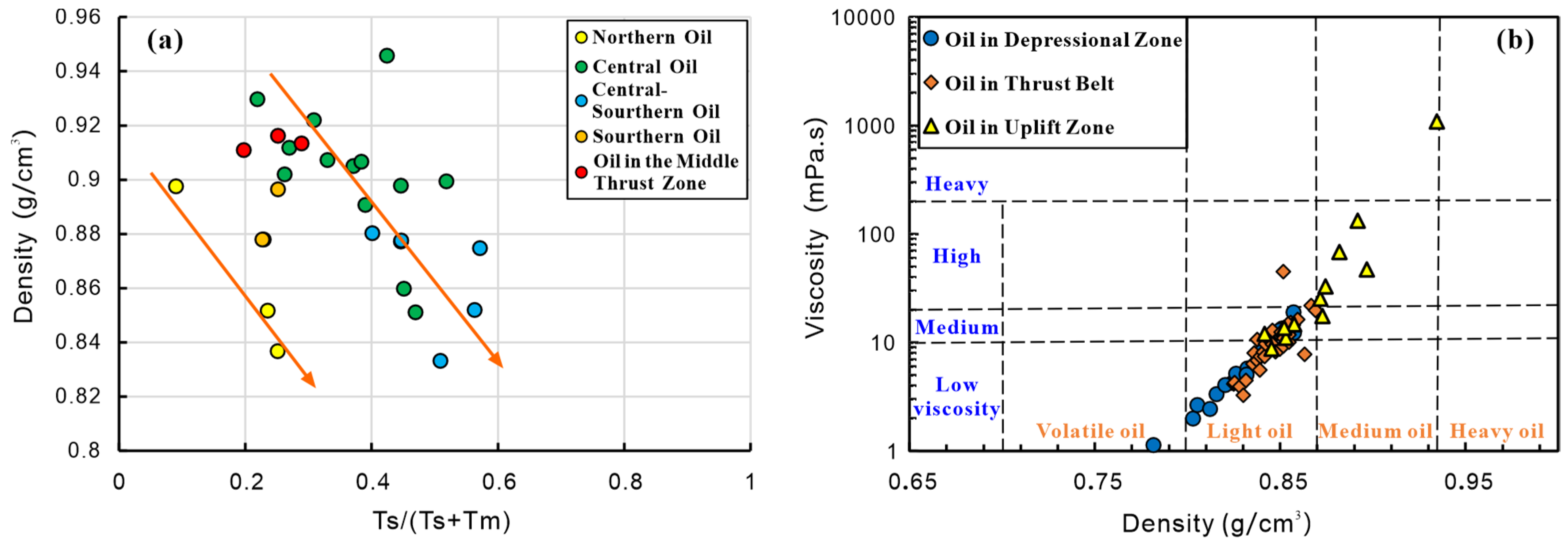

3.1. Oil Source Allocation Mechanism

3.2. Tracing of Crude Oil Migration Pathways

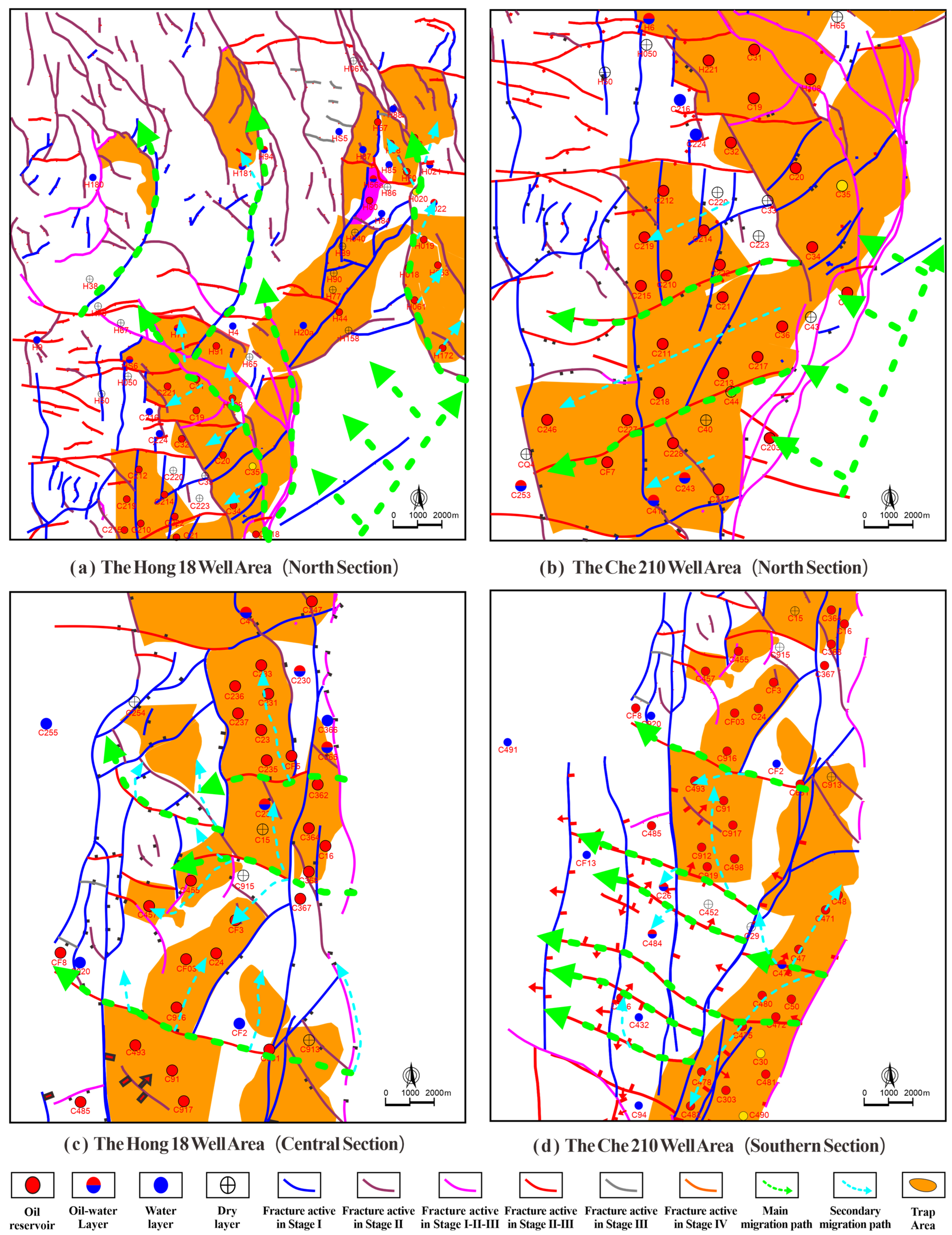

4. The Controlling Effect of the Fault System on Hydrocarbon Accumulation

4.1. Hydrocarbon Transport Systems

4.2. Fault-Controlled Charging Process

- Stage I faults act as reservoir-controlling faults

- 2.

- Stage II and III faults control charging pathways and charging directions

- 3.

- Stage IV faults control controls Charge process in the Meso-Cenozoic reservoirs

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Vertically, the Hongche Fault Zone has experienced “three Stages of thrusting and one Stage of weak extensional depression”, resulting in “three major deformation zones and six sets of fault systems”. The long term thrusting of active faults has created an alternating pattern of uplifts and depressions.

- (2)

- The fault system in the study area is characterized by multi-stage and multi-trend composite development. The NNE-trending faults were mainly formed in Stage I, controlled by the NWW-directed compressive stress. Most of them only showed activity in Stage I or continued to be active until Stage III. The NNW-trending faults mainly started to be active in Stage II or were active from Stage I to Stage III, reflecting the transformation of the tectonic stress field in the Late Triassic.

- (3)

- The oil sources of the Carboniferous reservoirs in the Hongche Fault Zone are mainly from the source rocks of the Permian Fengcheng Formation and the Lower Wuerhe Formation in the Shawan Sag. Tracer analysis of the migration path indicates that the migration of crude oil is mainly controlled by faults active during Thrusting Episodes II and III.

- (4)

- The faults active at different stages in the Hongche Fault Zone controlled the hydrocarbon accumulation process of the Carboniferous reservoirs. The Stage I faults mainly act as reservoir-controlling faults. The Stage II and III faults serve as the primary migration pathways for hydrocarbons in the Carboniferous reservoirs. They control the hydrocarbon charging pathways, charging directions, and readjustment of hydrocarbon accumulation. The Stage IV faults are of great significance for the hydrocarbon conduction in the Meso-Cenozoic reservoirs of the study area.

- (5)

- This research provides theoretical guidance for optimizing exploration targets and reserve development in Carboniferous reservoirs of the Hongche Fault Zone.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Q. Study on the Difference in the Evolution Mechanism of Strike-Slip Fault System and Its Relationship with Oil and Gas Distribution in the Western Depression of Liaohe Subbasin. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeast Petroleum University, Daqing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ma, Q. Zonal Differential Deformation and Reservoir Control Model of Ordovician Strike-Slip Fault Zone in Tahe Oilfield. Mar. Orig. Pet. Geol. 2022, 27, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Chen, F.; Jia, Z. Types and Tectonic Evolution of Junger Basin. Earth Sci. Front. 2000, 7, 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Xu, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, D.; Liu, W. Characteristics of Strike-Slip Faults in the Northwestern Margin of Junggar Basin and Their Geological Significance for Petroleum. Geol. J. China Univ. 2008, 14, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wu, K.; Ren, B. Deformation Mechnisim and Petroleum Accumulation of the High Angle Fault in the Western Circle Zone of Mahu Depression, Junggar Basin. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2016, 34, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Guo, S.; Qi, J.; Xing, X. Three-Stage Strike-Slip Fault Systems at the Northwestern Margin of the Junggar Basin and Their Implications for Hydrocarbon Exploration. Oil Gas Geol. 2016, 37, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Li, B.; Hou, L.; He, D.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y. New Hydrocarbon Exploration Areas in Footwall-Covered Structures of the Northwestern Margin of the Junggar Basin. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2008, 35, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Li, J.; Pan, T.; Xu, Q.; Chen, L.; Ren, J.; Jin, K. Hydrocarbon Accumulation Conditions and Exploration Potential of Hongche Fault Zone in Junggar Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2023, 44, 748–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, W.; Yao, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y. The Permian Hybrid Petroleum System in the Northwest Margin of the Junggar Basin, Northwest China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2005, 22, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Jia, C.; Guo, J.; Li, S. Characteristics, Formation and Evolution of Fault System in Zhongguai Uplift of Junggar Basin, China. J. Earth Sci. Environ. 2017, 39, 406–418. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Luo, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Ma, W.; Chen, S.; He, C. A Geochemical Evaluation Method of Fault Sealing Evolution and Its Controlling Effect on Hydrocarbon Accumulation: A Case Study of the Hongche Fault Zone in the North-West Margin of the Junggar Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2023, 43, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Guo, J.; Yao, W.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B. Analysis on the Structure and Accumulation Differences of Hongche Fault Belt in Junggar Basin. Geol. Resour. 2019, 28, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Feng, C.; Zhou, F.; Feng, Z.; Sun, T.; Gao, Z.; Pu, Y.; Zhou, L. Lithology and Lithofacies Characteristics Analysis and Reservoir Identification of Carboniferous Volcanic Rocks in Hongche Fault Zone. J. China Univ. Pet. (Ed. Nat. Sci.) 2023, 47, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, S.; Xiang, K.; Chen, G.; Zhu, C.; Wei, X. Oil-Water Inversion and Its Generation at Top and Bottom of the Shallow Sandstone Reservoir in the Northern Chepaizi Area, Junggar Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2014, 41, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Chen, Z.; Hu, T.; Liang, Z.; Jia, C.; Wu, K.; Pan, T.; Yu, H.; Dang, Y. Storage Space, Pore Structure, and Primary Control of Igneous Rock Reservoirs in Chepaizi Bulge, Junggar Basin, Western China: Significance for Oil Accumulation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 195, 107836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; He, Q. Geochemical Characteristics of Source Rocks and Gas Exploration Direction in Shawan Sag, Junggar Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2022, 33, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Liu, T.; Shi, B.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, Z. Genesis of Heavy Oils and Hydrocarbon Accumulation Process in Chepaizi Uplift (NW Junggar Basin). Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 18610–18630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, D.; Song, Y.; Zheng, M.; Qin, Z.; Gong, D. Genetic Types, Origins, and Accumulation Process of Natural Gas from the Southwestern Junggar Basin: New Implications for Natural Gas Exploration Potential. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 123, 104727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Hu, S.; Gong, D.; You, X.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, X. Natural Gas Exploration Potential and Favorable Targets of Permian Fengcheng Formation in the Western Central Depression of Junggar Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; He, D.; Lei, Z. Sedimentary Response to the Activity of the Permian Thrusting Fault in the Foreland Thrust Belt of the Northwestern Junggar Basin. Acta Geol. Sin. 2004, 78, 612–625. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.-Q.; Yu, F.-S.; Wang, Y.-F.; Shen, Z.-Y.; Xiu, J.-L.; Xue, Y.; Shao, L.-F. Multi-Phase Deformation and Analogue Modelling of the Junggar Basin, NW China. Pet. Sci. 2024, 21, 3720–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Jin, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y. Improved Understanding of Petroleum Migration History in the Hongche Fault Zone, Northwestern Junggar Basin (Northwest China): Constrained by Vein-Calcite Fluid Inclusions and Trace Elements. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2010, 27, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Study on Hydrocarbon Accumulation Law for Volcanic Rockreservoirs in Hongche Fault Belt, Junggar Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Yu, Q.; Li, X. Re-Understanding of the Carboniferous and the Characteristics of Hydrocarbon Accumulation in the Hongche Fault Zone of the Junggar Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2024, 45, 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Han, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S. Tectonic Layer Division and Its Tectonic Significance in the Middle-Cenozoic Red Layer in the Western Qinling Mountains. Geol. Rev. 2014, 60, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Neto, E.R.; Fatah, T.Y.A.; Dias, R.M.; Freire, A.F.M.; Lupinacci, W.M. Curvature Analysis and Its Correlation with Faults and Fractures in Presalt Carbonates, Santos Basin, Brazil. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 158, 106572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Pan, Y.; Wang, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, W.; Wu, S. Normal Fault Genesis Mechanism in Foreland Tectonic Superposition Area in Northern Sichuan Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2025, 46, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, S.; Yang, X.; Hu, M.; Xie, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, G.; Luo, H.; et al. Episodic Thrusting and Sequence-Sedimentary Responses and Their Petroleum Geological Significance in Kuga Foreland Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tong, H.; He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ren, X.; Ren, X.; Deng, C.; Yin, Y. Structural Analysis of Oblique Extrusion Superposition Deformation: A Case Study of Weiyuan Area in Sichuan. Acta Geol. Sin. 2023, 97, 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Chen, C.; Feng, J. Structural Characters and Evolution of the Mid South Section at the West Margin of Ordos Basin. Geoscience 2012, 26, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Dong, J.; Wei, G.; Li, B.; Zeng, Q.; Yang, G. Hidden Rift Basin and Its Hydrocarbon Geological Significance under the Thin-Skin Thrust Structure in the Southern Foreland Basin of Western Sichuan. Oil Gas Geol. 2006, 27, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Sun, J.; Liang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, J. Fault Characteristics and Reservoir Potential of Mesozoic Basins in the Southern East China Sea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ding, W.; Dai, J.; Wu, Z.; Yang, H. Quantitative Prediction of Lower Order Faults Based on the Finite Element Method: A Case Study of the M35 Fault Block in the Western Hanliu Fault Zone in the Gaoyou Sag, East China. Tectonics 2018, 37, 3479–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weert, A.; Camanni, G.; Mercuri, M.; Ogata, K.; Vinci, F.; Tavani, S. Displacement Analysis of Basin-Scale Reactivated Normal Faults: Insights from the West Netherlands Basin. J. Struct. Geol. 2025, 192, 105356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.N.; Shaw, J.H. Fault Displacement-Distance Relationships as Indicators of Contractional Fault-Related Folding Style. AAPG Bull. 2014, 98, 227–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Qin, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, F. Characteristics of Volcanic Reservoir Fractures in Upper Wall of HongChe Fault Belt. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2011, 32, 457–460. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zeng, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Geochemical Study of Oil and Gas Reservoir Formation of Hongche Area. J. Southwest Pet. Inst. 2004, 26, 1–4+97. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, W.; He, Q. Controlling Factors of Multi-Source and Multi-Stage Complex Hydrocarbon Accumulation and Favorable Exploration Area in the Hongche Fault Zone, Junggar Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2023, 34, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.E.; Moldowan, J.M. The Biomarker Guide: Interpreting Molecular Fossils in Petroleum and Ancient Sediments; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, T.; Chen, Z.; Dong, X.; Yao, W.; Liang, Z.; Wu, K.; Guan, J.; Gao, M.; Pang, Z.; Li, S.; et al. Oil Origin, Charging History and Crucial Controls in the Carboniferous of Western Junggar Basin, China: Formation Mechanisms for Igneous Rock Reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 203, 108600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, T.; Li, M.; Sajjad, A.; Lu, X.; Dai, J. Geochemistry and Origins of Petroleum in the Neogene Reservoirs of the Baiyun Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 107, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Wu, K.; Liu, Y.; Pei, Y.; Li, T. Cementing and Sealing Actions of Hongche Fault Belt in Zhongguai Area of Northwest Margin of Junggar Basin. Pet. Geol. Oilfield Dev. Daqing 2019, 38, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fault Activity Phase | Strike | Density | Extension Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | NNE-striking | Relatively High | Relatively Long |

| Phase II | NNW-striking | Relatively Low | Medium |

| Phase III | Near EW-striking | Medium | Relatively Short |

| Phase IV | EW-striking | Relatively High | Medium |

| Phase I–III | NNE and Near EW-striking | Medium to High | Relatively Long |

| Phase II–III | NNW, NNE and Near SN-striking | Relatively Low | Medium |

| Region | β-Carotane | Pr/Ph | Ga/C30H | C24Tet/C26TT | TS/(Ts + Tm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Area | High | 0.80~1.10 | 0.19~0.49 | 0.27~0.49 | 0.05~0.41 |

| Central Area | High | 0.58~1.23 | 0.07~0.65 | 0.16~0.48 | 0.20~0.52 |

| Central-Southern Area | High | / | 0.23~0.33 | 0.17~0.35 | 0.32~0.57 |

| Southern Area | Low-Middle | / | 0.12~0.23 | 0.48~0.84 | 0.23~0.46 |

| Middle Thrust Zone | Middle | 1.1~2.0 | 0.07~0.29 | 0.39~0.77 | 0.20~0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, H.; Yang, X.; Han, J.; Fu, J.; Hao, M.; Song, Y. Controls of Fault System on Hydrocarbon Accumulation: A Case Study from the Carboniferous Reservoir of the Hongche Fault Zone in the Junggar Basin. Processes 2025, 13, 4054. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124054

Huang C, Sun Y, Zhou H, Yang X, Han J, Fu J, Hao M, Song Y. Controls of Fault System on Hydrocarbon Accumulation: A Case Study from the Carboniferous Reservoir of the Hongche Fault Zone in the Junggar Basin. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4054. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124054

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Cheng, Yonghe Sun, Huafeng Zhou, Xiaofan Yang, Junwei Han, Jian Fu, Mengyuan Hao, and Yulin Song. 2025. "Controls of Fault System on Hydrocarbon Accumulation: A Case Study from the Carboniferous Reservoir of the Hongche Fault Zone in the Junggar Basin" Processes 13, no. 12: 4054. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124054

APA StyleHuang, C., Sun, Y., Zhou, H., Yang, X., Han, J., Fu, J., Hao, M., & Song, Y. (2025). Controls of Fault System on Hydrocarbon Accumulation: A Case Study from the Carboniferous Reservoir of the Hongche Fault Zone in the Junggar Basin. Processes, 13(12), 4054. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124054