Harnessing Algal–Bacterial Nexus for Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wastewater Characterization

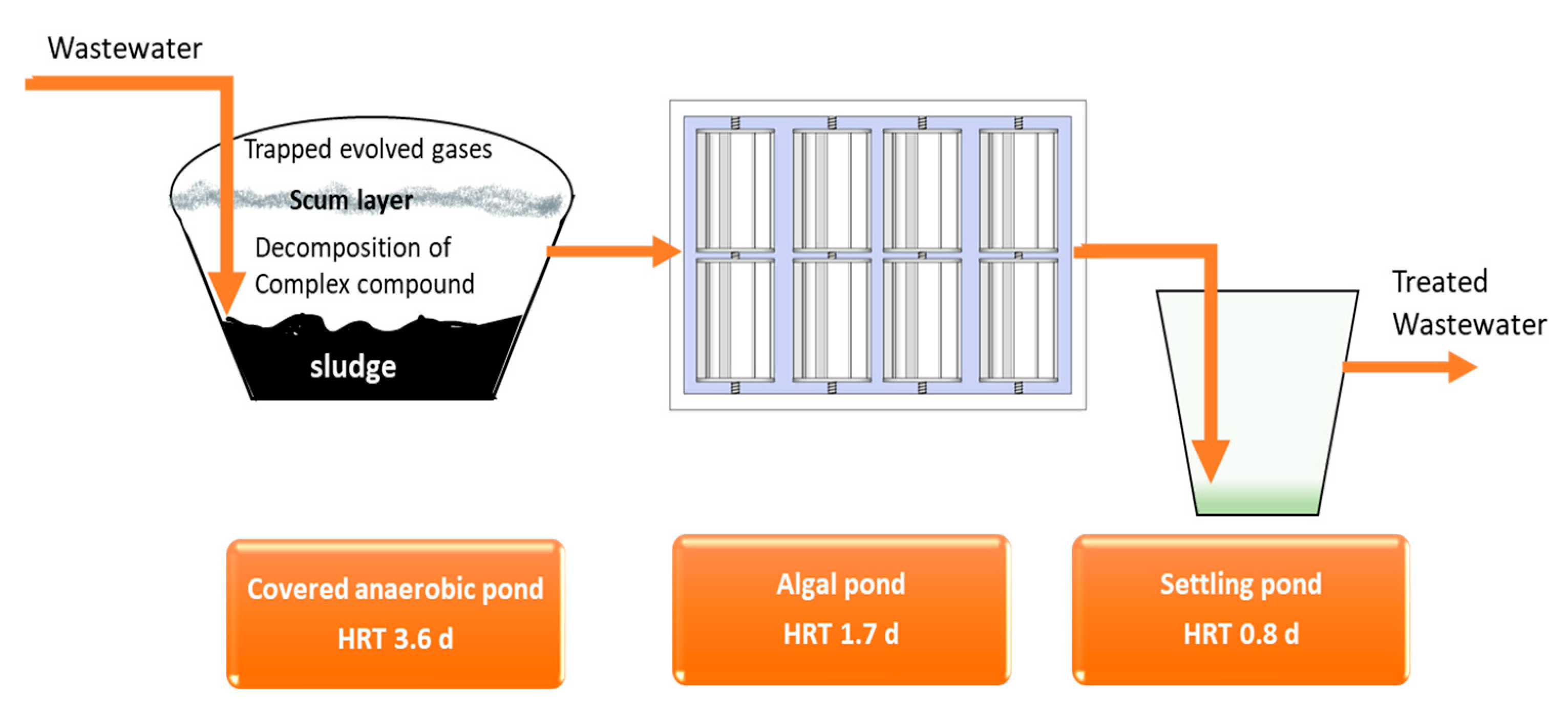

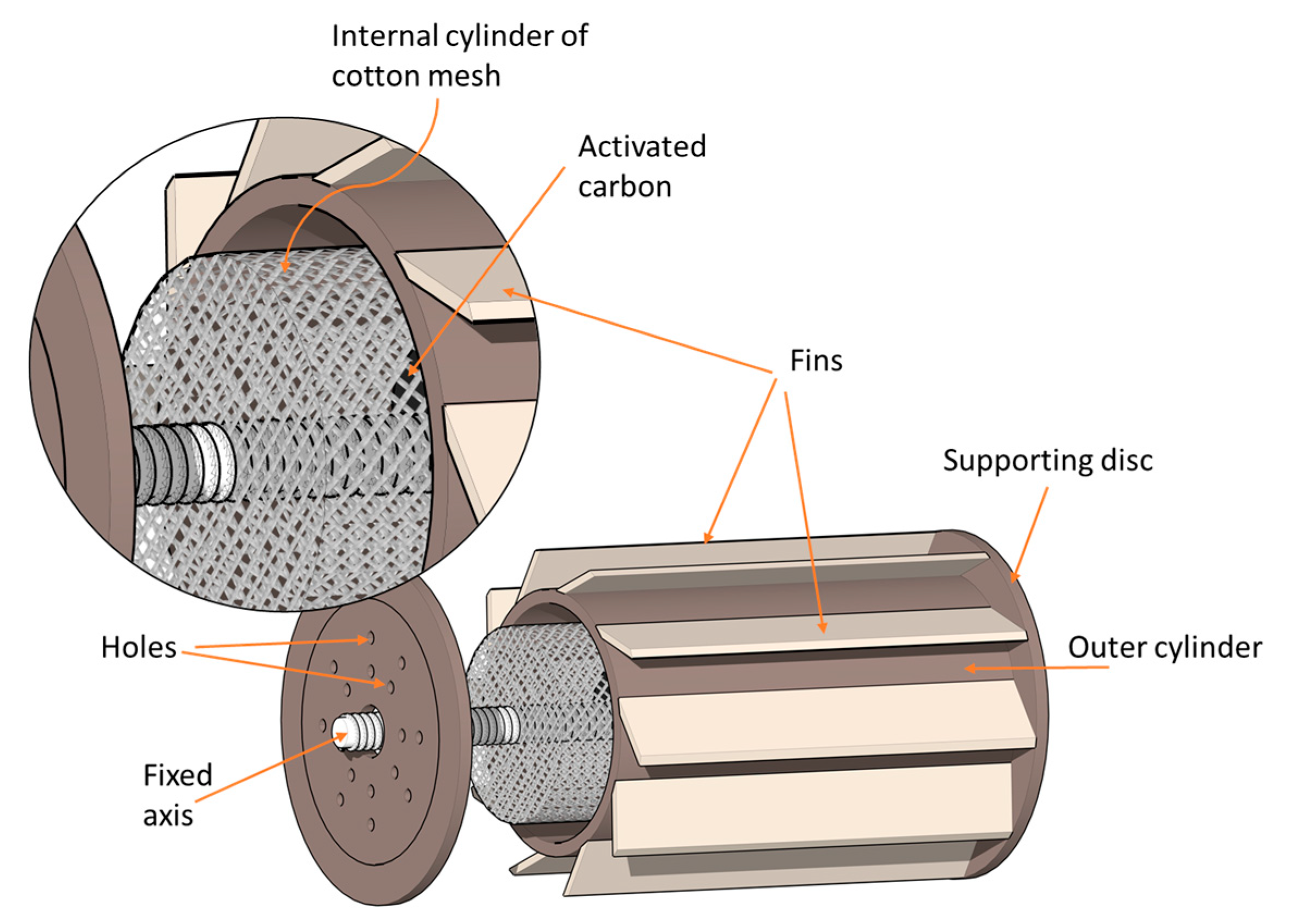

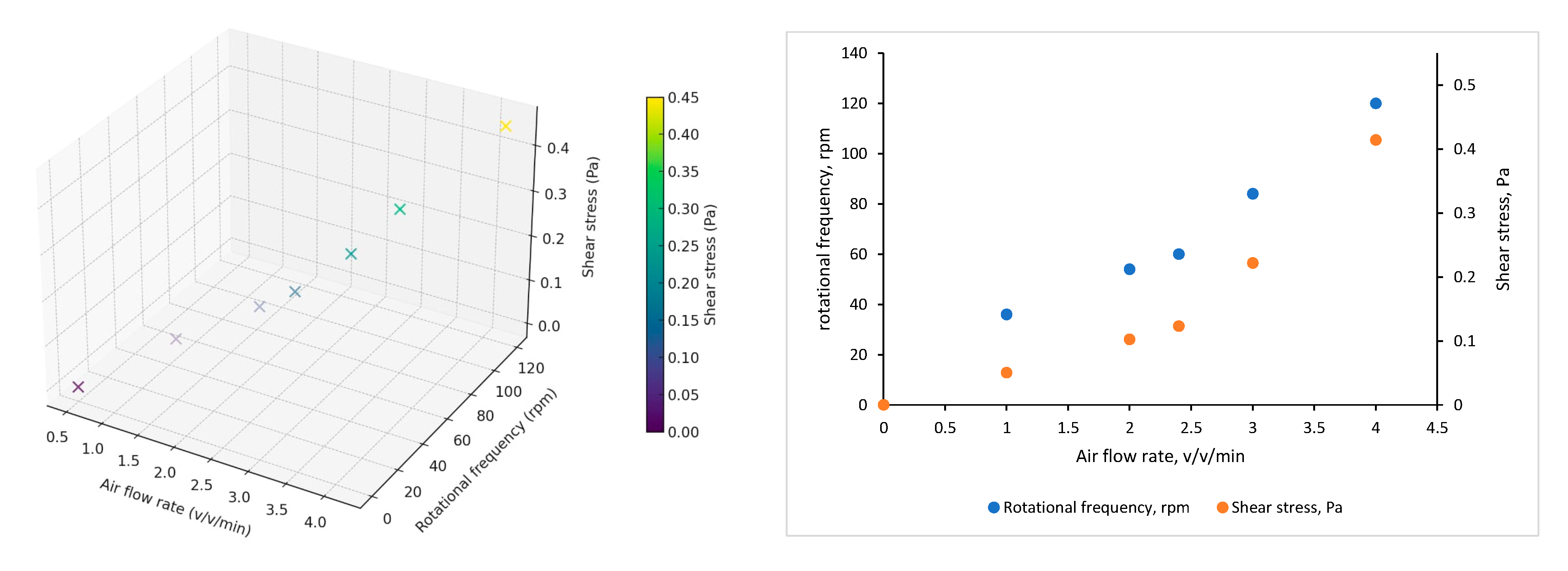

2.2. System Description

2.3. System Monitoring

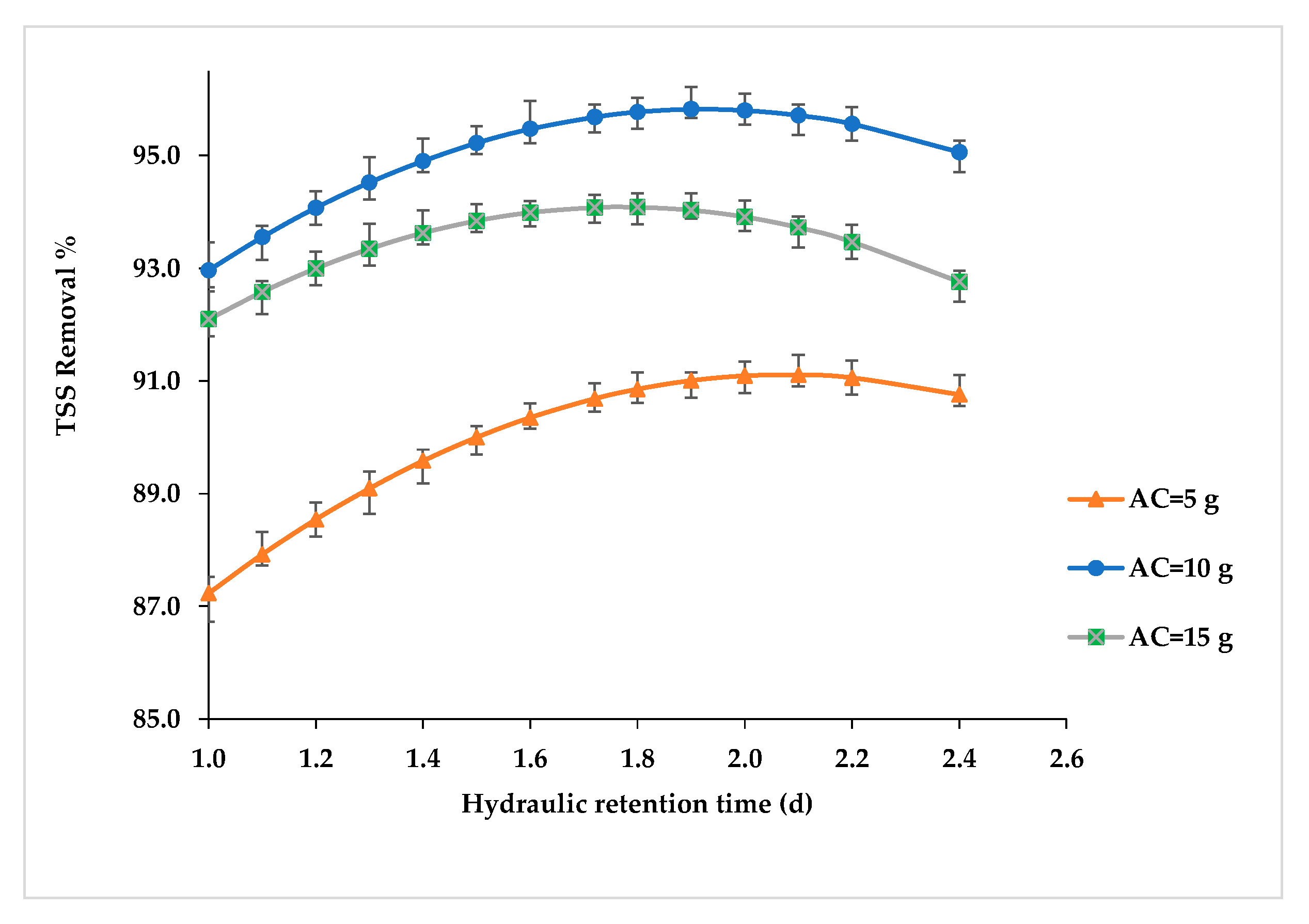

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BOD | Biological oxygen demand |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| EBS | Extracellular polymeric substance |

| HRAP | High-rate algal pond |

| HRT | Hydraulic retention time |

| RBC | Rotating biological contactors |

| TSS | Total suspended solids |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| WWT | Wastewater treatment |

| WWTP | Wastewater treatment plant |

References

- Rathod, S.V.; Saras, P.; Gondaliyam, S.M. Environmental pollution: Threats and challenges for management. In Eco-Restoration of Polluted Environment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, Z.; Sultana, F.M.; Mushtaq, F. Environmental Pollution Control Measures and Strategies: An Overview of Recent Developments. In Geospatial Analytics for Environmental Pollution Modeling; Mushtaq, F., Farooq, M., Mukherjee, A.B., Ghosh Nee Lala, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaideen, K.; Shehata, N.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Olabi, A.G. The role of wastewater treatment in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and sustainability guideline. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fito, J.; Van Hulle, S.W. Wastewater reclamation and reuse potentials in agriculture: Towards environmental sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 2949–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimongkol, P.; Sangtanoo, P.; Songserm, P.; Watsuntorn, W.; Karnchanatat, A. Microalgae-based wastewater treatment for developing economic and environmental sustainability: Current status and future prospects. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 904046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Muñoz, C.A.; de Godos, I.; Muñoz, R. Wastewater treatment using photosynthetic microorganisms. Symmetry 2023, 15, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, H.; Gautam, S.; Bapodariya, H.; Maliwad, M.B.; Gangawane, A.K.; Kaushal, R.S. Bioremediation of waste water: In-depth review on current practices and promising perspectives. J. Aquac. Trop. 2022, 37, 117–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, R.; Parnian, A.; Mahbod, M.; AbdelRahman, M.A. Bioremediation: A better technique for wastewater treatment and resource recovery. In Biotechnologies for Wastewater Treatment and Resource Recovery, 1st ed.; Kumar, A., Parnian, A., AbdelRahman, M.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahal, S.; Khaturia, S.; Joshi, N. Application of microbial enzymes in wastewater treatment. In Genomics Approach to Bioremediation: Principles, Tools, and Emerging Technologies; Kumar, V., Bilal, M., Romanholo Ferreira, L.F., Iqbal, H.M.N., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Hassan, L.H.; El-Sheekh, M. Microalgae-mediated bioremediation: Current trends and opportunities-a review. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mekkawi, S.A.; Doma, H.S.; Ali, G.H.; Abdo, S.M. Case study: Effective use of microphytes in wastewater treatment, profit evaluation, and scale-up life cycle assessment. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 41, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruas, G.; Lacerda, S.F.; Nantes, M.A.; Serejo, M.L.; da Silva, G.H.R.; Boncz, M.Á. CO2 addition and semicontinuous feed regime in shaded HRAP—Pathogen removal performance. Water 2022, 14, 4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.C.; Hu, Y.R.; He, Z.W.; Li, Z.H.; Tian, Y.; Wang, X.C. Promoting symbiotic relationship between microalgae and bacteria in wastewater treatment processes: Technic comparison, microbial analysis, and future perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 206, 155703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanker, R.; Khatana, K.; Verma, K.; Singh, A.; Kumar, R.; Mohamed, H.I. An integrated approach of algae-bacteria mediated treatment of industries generated wastewater: Optimal recycling of water and safe way of resource recovery. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 54, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaceri, H.; Ishika, T.; Mkpuma, V.O.; Moheimani, N.R. Microalgal biofilms: Towards a sustainable biomass production. Algal Res. 2023, 72, 103124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, E.; Kim, H.; Kim, G.; Lee, D. A review of bacterial biofilm formation and growth: Rheological characterization, techniques, and applications. Korea-Aust. Rheol. J. 2023, 35, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Patil, S.A.; Nancharaiah, Y.V. Environmental microbial biofilms: Formation, characteristics, and biotechnological applications. In Material-Microbes Interactions; Aryal, N., Zhang, Y., Patil, S.A., Pant, D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, A.; Rocha, V.; Barros, O.; Silva, B.; Tavares, T. Bacterial biofilm attachment to sustainable carriers as a clean-up strategy for wastewater treatment: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 63, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Chakraborty, P.; Das, S.; Sarkar, S.; Gupta, A.D.; Roy, R.; Malik, M.; Tribedi, P. Microbial Biofilms in Wastewater Treatment: A Sustainable Approach. In Application of Microbial Technology in Wastewater Treatment and Bioenergy Recovery; Ray Chaudhuri, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Dhiman, S. Microbial Biofilms in Wastewater Remediation. In Microbial Technologies in Industrial Wastewater Treatment; Shah, M.P., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahto, K.U.; Das, S. Bacterial biofilm and extracellular polymeric substances in the moving bed biofilm reactor for wastewater treatment: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 345, 126476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tan, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, C.; Yan, X.; Xu, Q.; Ruan, R.; Cheng, P. The intrinsic characteristics of microalgae biofilm and their potential applications in pollutants removal—A review. Algal Res. 2022, 68, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ministry of Housing Utilities and Urban Communities. ECP 501: Egyptian Code of Wastewater Reuse; The Ministry of Housing Utilities and Urban Communities ECP 501/2015; The Ministry of Housing Utilities and Urban Communities: Cairo, Egypt, 2015.

- Elbana, T.A.; Bakr, N.; Elbana, M. Reuse of Treated Wastewater in Egypt: Challenges and Opportunities. In Unconventional Water Resources and Agriculture in Egypt; The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Negm, A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 75, pp. 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA—American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association; Water Environment Federation. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Sewage, 24th ed.; LMC—Pharma Books: Vaughan, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mekkawi, S.A.; Abdo, S.M.; Youssef, M.; Ali, G.H. Optimizing performance efficiency of algal-bacterial-based wastewater treatment system using response surface methodology. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 26, 101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalima, M.P.G.; Monteros, D.A.N. Evaluation of the rotational speed and carbon source on the biological removal of free cyanide present on gold mine wastewater, using a rotating biological contactor. J. Water Process Eng. 2018, 23, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnoni, L.I.; Cubitto, M.A.; Lozano, J.E. Role of shear stress on biofilm formation of Candida krusei in a rotating disk system. J. Food Eng. 2011, 102, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagkari, E.; Connelly, S.; Liu, Z.; McBride, A.; Sloan, W.T. The role of shear dynamics in biofilm formation. npj Biofilm. Microbiomes 2022, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, S.M.; Youssef, A.M.; El-Liethy, M.A.; Ali, G.H. Preparation of simple biodegradable, nontoxic, and antimicrobial PHB/PU/CuO bionanocomposites for safely use as bioplastic material packaging. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 14, 28673–28683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

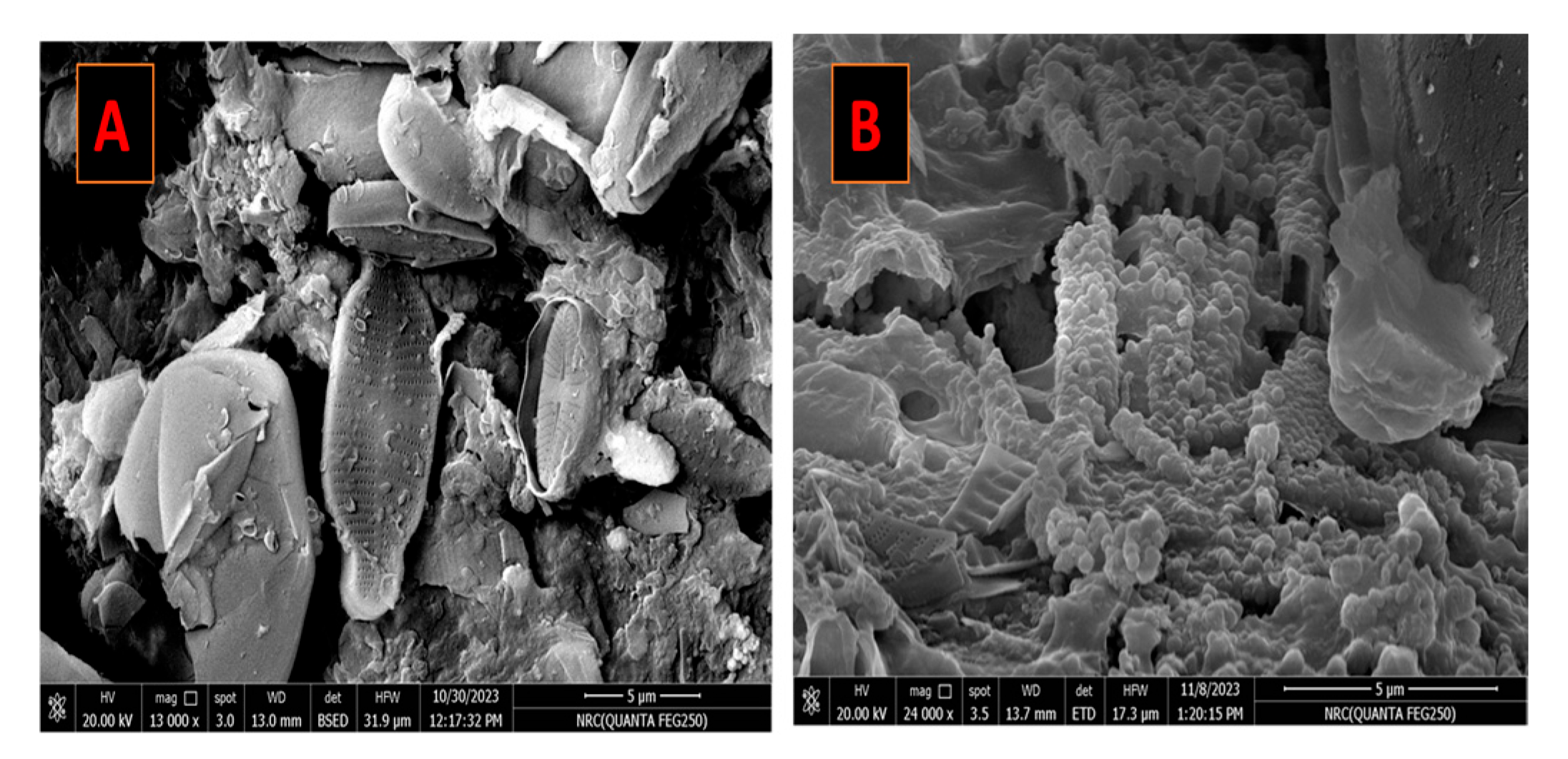

- Grossart, H.P.; Levold, F.; Allgaier, M.; Simon, M.; Brinkhoff, T. Marine diatom species harbour distinct bacterial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 7, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, C.D.; Castillo, F.; Pérez, V.; Riquelme, C. Inhibition of Nitzschia ovalis biofilm settlement by a bacterial bioactive compound through alteration of EPS and epiphytic bacteria. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, R.; Oon, Y.L.; Oon, Y.S.; Bi, Y.; Mi, W.; Song, G.; Gao, Y. Diverse interactions between bacteria and microalgae: A review for enhancing harmful algal bloom mitigation and biomass processing efficiency. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hong, Y. Microalgae biofilm and bacteria symbiosis in nutrient removal and carbon fixation from wastewater: A review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2022, 8, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Schideman, L.C.; Canam, T.; Hosen, J.D.; Hudson, R.J. Spatial and temporal differences in the composition and structure of bacterial assemblages in biofilms of a rotating algal-bacterial contactor system treating high-strength anaerobic digester filtrate. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 10, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanova, V.; Spetea, C. Mixotrophy in diatoms: Molecular mechanism and industrial potential. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyshchenko, A.; Roberts, W.R.; Ruck, E.C.; Lewis, J.A.; Alverson, A.J. The genome of a nonphotosynthetic diatom provides insights into the metabolic shift to heterotrophy and constraints on the loss of photosynthesis. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 1750–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, P.; Liu, X.; Nan, F.; Liu, Q.; Lv, J.; Feng, J.; Xie, S. The complex relationships between diatoms, bacterial communities, and dissolved organic matter: Effects of silicon concentration. Algal Res. 2024, 79, 103460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.Y.; Honda, K.; Derek, C.J.C. A review on microalgal-bacterial Co-culture: The multifaceted role of beneficial bacteria towards enhancement of microalgal metabolite production. Environ. Res. 2023, 228, 115872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, J.A.; Muñoz, R.; Donoso-Bravo, A.; Bernard, O.; Casagli, F.; Jeison, D. A half-century of research on microalgae-bacteria for wastewater treatment. Algal Res. 2022, 67, 102828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Yamada, R.; Matsumoto, T.; Ogino, H. Co-culture systems of microalgae and heterotrophic microorganisms: Applications in bioproduction and wastewater treatment and elucidation of mutualistic interactions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, X.; Kumar, K.; Kunetz, T.; Zhang, Y.; Gross, M.; Wen, Z. Removing high concentration of nickel (II) ions from synthetic wastewater by an indigenous microalgae consortium with a Revolving Algal Biofilm (RAB) system. Algal Res. 2021, 59, 102464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompei, C.M.E.; Ruas, G.; Bolzani, H.R.; da Silva, G.H.R. Assessment of total coliforms and E. coli removal in algae-based pond under tropical temperature in addition of carbon dioxide (CO2) and shading. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 196, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botavara, L.A.; Ragaza, J.A.; Lim, H.C.; Teng, S.T. Morphological and molecular characterization of two potentially toxigenic species of the genus Pseudo-nitzschia (Bacillariophyceae) in Luzon Island, Philippines. Diatom Res. 2024, 39, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Value | SD * |

|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical characteristics | ||

| pH | 7.3 | 0.4 |

| Chemical oxygen demand (COD) | 101 mgO2/L | 2.3 |

| Biological oxygen demand (BOD) | 21 mgO2/L | 1.2 |

| Turbidity | 24 NTU | 0.9 |

| Total suspended solids (TSS) | 61 mg/L | 1.1 |

| Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN) | 25 mg/L | 0.7 |

| Ammonia | 6 mg/L | 0.5 |

| Nitrite | 0 | 0 |

| Nitrate | 0.2 mg/L | 0.1 |

| Total phosphorus | 1.5 mg/L | 0.6 |

| Biological characteristics | ||

| E. coli | 5.4 × 104 MPN/100 mL | |

| Fecal coliform | 3.7 × 106 MPN/100 mL | |

| Total coliform | 9.4 × 106 MPN/100 mL | |

| Algal species exist in wastewater. | Scenedesmus obliquus, Stephanodiscus sp., Cyclotella comta, Nitzschia linearis, Microcystis sp., Oscillatoria limnetica, Ankistrodesmus acicularis, Selenastrum sp., Chlorella vulgaris. | |

| Wastewater Characteristics | Treated Wastewater Characteristics | Egyptian Code 501/2015 [23,24] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade A | Grade B | Grade C | Grade D | |||

| TSS, mg/L | 61 | 3 | 15 | 30 | 50 | 300 |

| Turbidity, NTU | 24 | 0.9 | 5 | undefined | undefined | undefined |

| BOD, mg/L | 21 | 3.2 | 15 | 30 | 80 | 350 |

| E. coli, MPN/100 mL | 5.4 × 104 | ND * | 20 | 100 | 1000 | undefined |

| Microalgae Strain | Raw Wastewater | Microalgae Pond | Pond’s Wall | Rotating Body |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitzschia linearis | + | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Cyclotella Comta | + | − | − | − |

| Stephanodiscus sp. | + | − | − | − |

| Scenedesmus obliquus | + | + | − | − |

| Chlorella vulgaris | + | ++++ | ++ | ++ |

| Selenastrum sp. | + | − | − | − |

| Ankistrodesmus acicularis | + | − | − | − |

| Oscillatoria limnetica | +++ | ++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Microscystis sp. | + | − | − | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El-Mekkawi, S.A.; Abdo, S.M.; Youssef, M. Harnessing Algal–Bacterial Nexus for Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Wastewater Treatment. Processes 2025, 13, 4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124042

El-Mekkawi SA, Abdo SM, Youssef M. Harnessing Algal–Bacterial Nexus for Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Wastewater Treatment. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124042

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl-Mekkawi, Samar A., Sayeda M. Abdo, and Marwa Youssef. 2025. "Harnessing Algal–Bacterial Nexus for Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Wastewater Treatment" Processes 13, no. 12: 4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124042

APA StyleEl-Mekkawi, S. A., Abdo, S. M., & Youssef, M. (2025). Harnessing Algal–Bacterial Nexus for Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Wastewater Treatment. Processes, 13(12), 4042. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124042