A Review of Lignocellulosic Biomass Alkaline Delignification: Feedstock Classification, Process Types, Modeling Approaches, and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Questions (RQs)

3. Literature Review

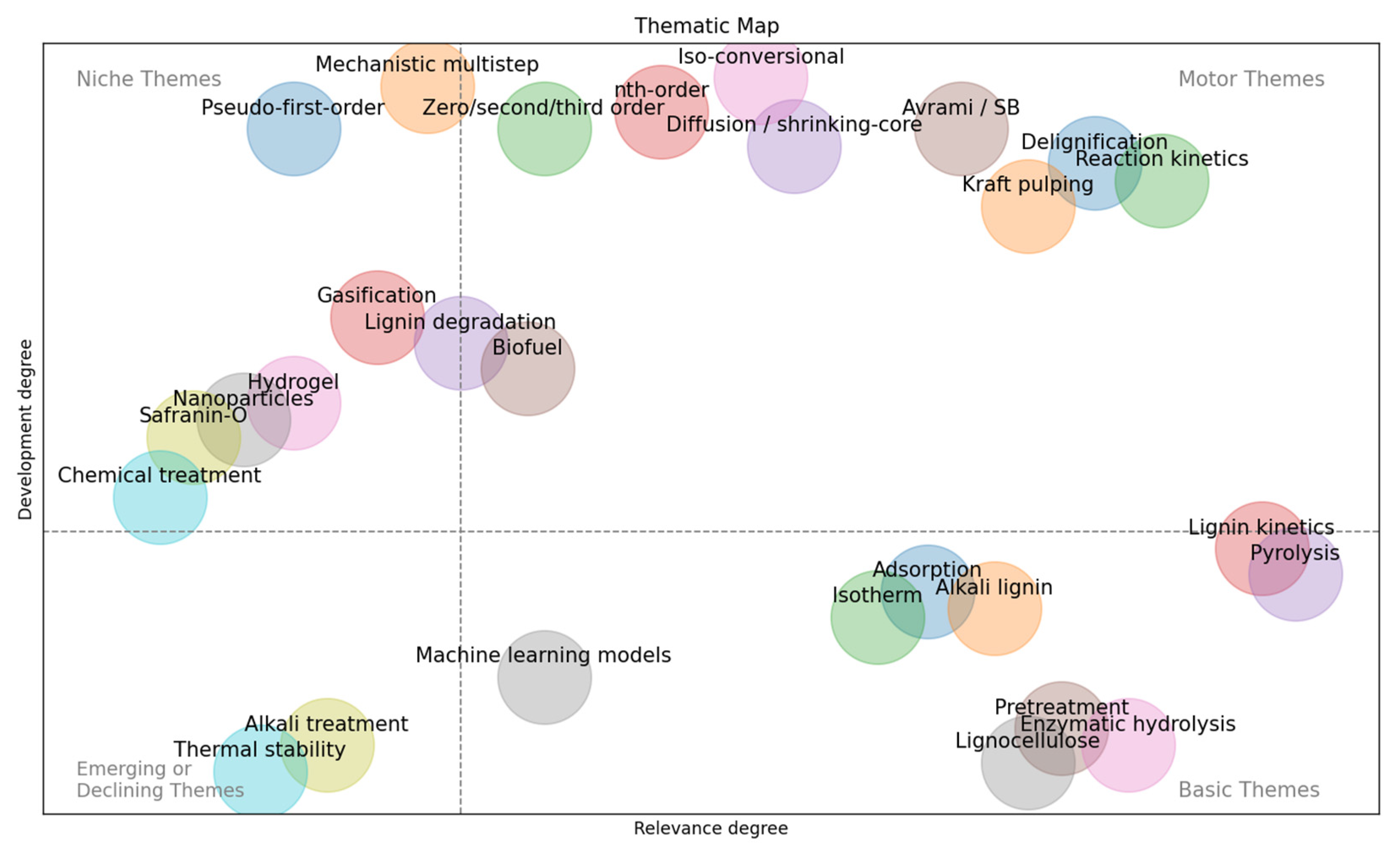

3.1. Literature Identification and Selection Process

3.2. Content Base Literature Analysis

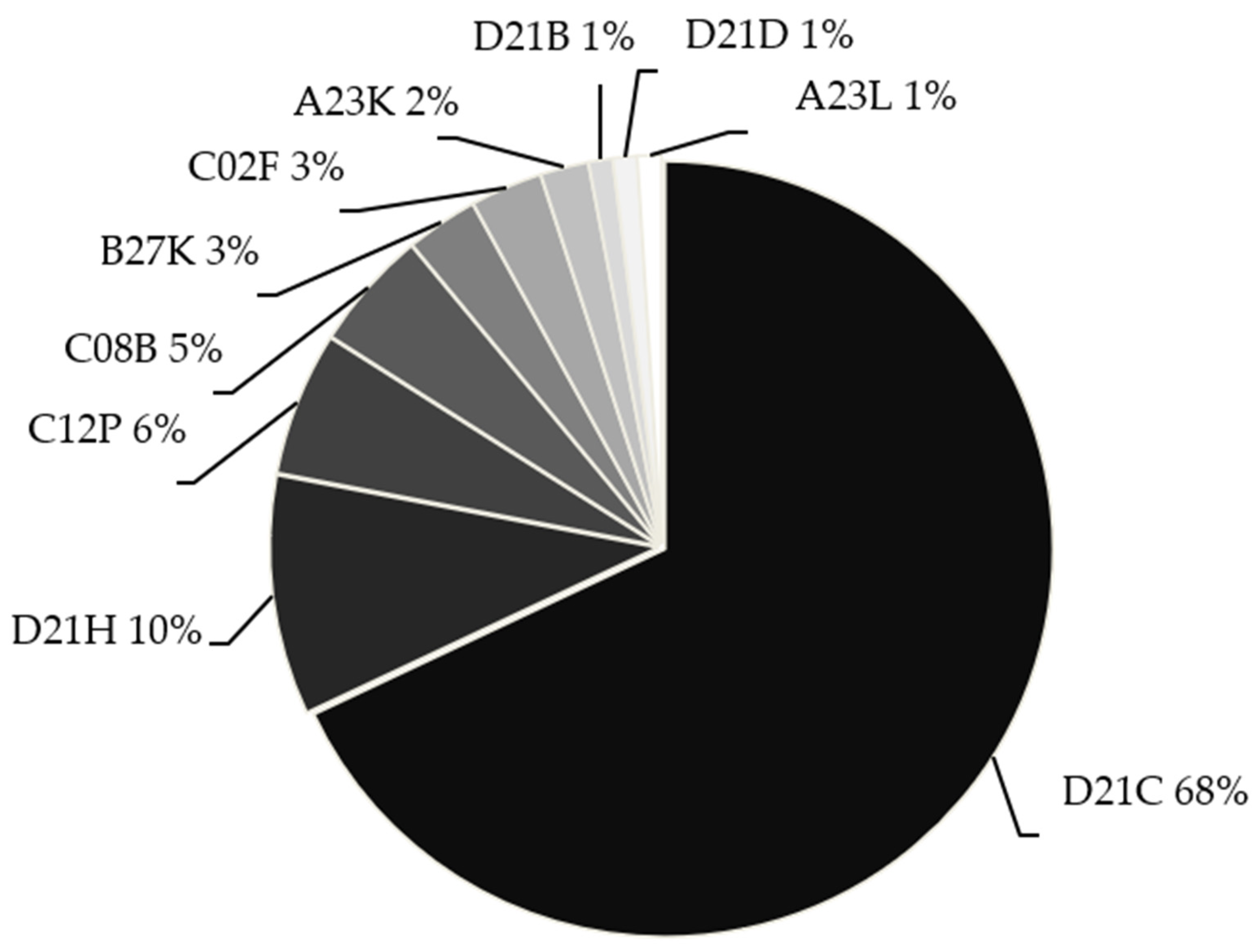

4. Patents Review

4.1. Patent Identification and Selection Process

- Identification of general IPC categories associated with the broader topic of delignification, including classes such as D21 (pulp production), C08B (modification of carbohydrates), C12P (fermentation/enzymatic treatment), and B27K (wood treatment).

- Selection of specific subcategories directly linked to alkaline delignification, such as D21C3/20 (alkaline pulping), D21H17/64 (fiber treatment with alkaline agents), or C08B1/00 (chemical modification of cellulose using alkalis). Patents that did not fall under any of the selected IPC codes were excluded.

4.2. IPC Categories Related to Alkaline Delignification

4.3. Chronological Overview of Patents Related to Alkaline Delignification

4.3.1. Early Foundations (1975–1985)

4.3.2. Contemporary Developments (2000–2025)

4.4. Global Trends in Patents Activity on Alkaline Delignification

5. Discussion

5.1. Status and Research Outlook

5.2. Research Gaps and Opportunities

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DL | Delignification |

| IPC | International Patent Classification |

| NaOH | Sodium Hydroxide |

| KOH | Potassium Hydroxide |

| AQ | Anthraquinone |

| DES | Deep Eutectic Solvent |

| LTTM | Low-Transition-Temperature Mixture |

| SCP | Shrinking Core Model |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric Analysis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

References

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Kim, T.H. A Review on Alkaline Pretreatment Technology for Bioconversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C.; Duque, A.; Sánchez-Monedero, A.; González, E.J.; González-Miquel, M.; Cañadas, R. Exploring Recent Advances in Lignocellulosic Biomass Waste Delignification Through the Combined Use of Eutectic Solvents and Intensification Techniques. Processes 2024, 12, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Esteves, B.; Evtuguin, D.V. Microwaves and Ultrasound as Emerging Techniques for Lignocellulosic Materials. Materials 2023, 16, 7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, M.S.; Sowjanya, S.; Nath, P.C.; Chakraborty, A.; Amrit, R.; Mishra, B.; Mishra, A.K.; Mohanta, Y.K. Valorisation of Agro-Industrial Wastes: Circular Bioeconomy and Biorefinery Process—A Sustainable Symphony. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 183, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Beltrán, J.U.; Hernández-De Lira, I.O.; Cruz-Santos, M.M.; Saucedo-Luevanos, A.; Hernández-Terán, F.; Balagurusamy, N. Insight into Pretreatment Methods of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Increase Biogas Yield: Current State, Challenges, and Opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelyn, E.; Okewale, A.O.; Owabor, C.N. Optimization, Kinetics and Thermodynamic Modeling of Pulp Production from Plantain Stem Using the Kraft Process. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2025, 11, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; He, J.; Pan, H.; Alonso-Riaño, P.; Amândio, M.S.T.; Xavier, A.M.R.B.; Beltrán, S.; Sanz, M.T.; Bañuelos, M. Subcritical Water as Pretreatment Technique for Bioethanol Production from Brewer’s Spent Grain within a Biorefinery Concept. Polymers 2022, 14, 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, Y.; Chen, P.; Peng, L. Ecologically Adaptable Populus simonii Is Specific for Recalcitrance-Reduced Lignocellulose and Largely Enhanced Enzymatic Saccharification among Woody Plants. GCB Bioenergy 2021, 13, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrhayam, Y.; Bennani, F.E.; Berradi, M.; El Yacoubi, A.; El Bachiri, A. Optimization of Eucalyptus Cellulose Fiber Using Response Surface Methodology: Effects of Sulfur Content and Refining Time on the Mechanical Characteristics of Paper Pulp. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 304, 127767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, A.; Ash, S.N.; Mahapatra, D.K. Pretreatment of Acacia Nilotica Sawdust by Catalytic Delignification and Its Fractal Kinetic Modeling. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. E 2016, 97, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoykova, T.H.R.; Radeva, G.V.; Nenkova, S.K. Comparative Kinetic Analysis of Poplar Biomass Alkaline Hydrolysis. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2016, 50, 269–274. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304349929_Comparative_kinetic_analysis_of_poplar_biomass_alkaline_hydrolysis (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Rauhala, T.; King, A.W.T.; Zuckerstätter, G.; Suuronen, S.; Sixta, H. Effect of Autohydrolysis on the Lignin Structure and the Kinetics of Delignification of Birch Wood. Nord. Pulp Paper Res. J. 2011, 26, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Vanska, E.; Van Heiningen, A. New Kinetics and Mechanisms of Oxygen Delignification Observed in a Continuous Stirred Tank Reactor. Holzforschung 2009, 63, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Rodríguez, F.; Gilarranz, M.A.; Moreno, D.; García-Ochoa, F. Kinetic Modeling of Kraft Delignification of Eucalyptus globulus. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 4114–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolk, M.; Yan, J.; McCarthy, J. Lignin 25. Kinetics of Delignification of Western Hemlock in Flow-through Reactors under Alkaline Conditions. Holzforschung 1989, 43, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedro, F.M.; Grénman, H.; Rissanen, J.V.; Salmi, T.; García-Serna, J.; Cocero, M.J. Chemical Composition and Extraction Kinetics of Holm Oak (Quercus ilex) Hemicelluloses Using Subcritical Water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2017, 129, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.L.; Dang, V.Q. The Fractal Nature of Kraft Pulping Kinetics Applied to Thin Eucalyptus Nitens Chips. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 64, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.Q.; Nguyen, K.L. A Universal Kinetic Equation for Characterising the Fractal Nature of Delignification of Lignocellulosic Materials. Cellulose 2007, 14, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, O.; Kuitunen, S.; Ruuttunen, K.; Alopaeus, V.; Vuorinen, T. Detailed Modeling of Kraft Pulping Chemistry. Delignification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 12977–12985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksi, S.; Sarkar, U.; Saha, S.; Ball, A.K.; Chandra Kuniyal, J.; Wentzel, A.; Birgen, C.; Preisig, H.A.; Wittgens, B.; Markussen, S. Studies on Delignification and Inhibitory Enzyme Kinetics of Alkaline Peroxide Pre-Treated Pine and Deodar Saw Dust. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2019, 143, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, V.; Nieminen, K.; Sixta, H.; van Heiningen, A. Delignification and Cellulose Degradation Kinetics Models for High Lignin Content Softwood Kraft Pulp during Flow-through Oxygen Delignification. Cellulose 2015, 22, 2055–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.L.; Liang, H. Kinetic Model of Oxygen Delignification. Part 1—Effect of Process Variables. Appita J. 2002, 55, 162–165. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287945189_Kinetic_model_of_oxygen_delignification_Part_1_-_Effect_of_process_variables (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Mendonça, R.; Guerra, A.; Ferraz, A. Delignification of Pinus Taeda Wood Chips Treated with Ceriporiopsis subvermispora for Preparing High-Yield Kraft Pulps. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2002, 77, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöblom, K. Extended Delignification in Kraft Cooking through Improved Selectivity Part 5. Influence of Dissolved Lignin on the Rate of Delignification. Nord. Pulp Paper Res. J. 1996, 11, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koncio, R.; Sarkanen, K.V. Kinetics of Lignin and Hemicellulose Dissolution during the Initial Stage of Alkaline Pulping. Holzforschung 1984, 38, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Gominho, J.; Rodrigues, J.C.; Miranda, I.; Pereira, H. Pulping Yield and Delignification Kinetics of Heartwood and Sapwood of Maritime Pine. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2005, 25, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijok, N.; Fiskari, J.; Gustafson, R.R.; Alopaeus, V. Modelling the Kraft Pulping Process on a Fibre Scale by Considering the Intrinsic Heterogeneous Nature of the Lignocellulosic Feedstock. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 438, 135548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, L.S.; Maass, O. A Preliminary Investigation of the Manner of Removal of Lignin from Spruce in Concentrated Sodium Hydroxide Solutions. Can. J. Res. 2011, 7, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocque, G.L.; Maass, O. The Mechanism of the Alkaline Delignification of Wood. Can. J. Res. 1941, 19b, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.Q.; Nguyen, K.L. A Universal Kinetic Model for Characterisation of the Effect of Chip Thickness on Kraft Pulping. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1486–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obst, J.R. Kinetics of Kraft Pulping of a Middle-Lamella—Enriched Fraction of Loblolly Pine. Tappi J. 1985, 68, 100–104. Available online: https://www.fpl.fs.usda.gov/documnts/pdf1985/obst85a.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Miao, G.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; He, L.; Xu, F. The Corrected H/G Factors for Accurately Describing the Delignification and Depolymerization of Industrial Hemp Stalks. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 219, 119074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, C.; Hu, Y.; Xia, C.; Sun, F.; Zhang, Z. Reaction Characteristics of Metal-Salt Coordinated Deep Eutectic Solvents during Lignocellulosic Pretreatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M.; Jain, S.K.; Devnani, G.L.; Sonawane, S.R.S.; Singh, D. Thermal Kinetics and Morphological Investigation of Alkaline Treated Rice Husk Biomass. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022, 99, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muharja, M.; Fitria Darmayanti, R.; Palupi, B.; Rahmawati, I.; Arief Fachri, B.; Arie Setiawan, F.; Wika Amini, H.; Fitri Rizkiana, M.; Rahmawati, A.; Susanti, A.; et al. Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Alkali Pretreatment for Enhancement of Delignification Process of Cocoa Pod Husk. Bull. Chem. React. Eng. Catal. 2021, 16, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, F.; Şenol, H.; Papirio, S. Enhanced Lignocellulosic Component Removal and Biomethane Potential from Chestnut Shell by a Combined Hydrothermal–Alkaline Pretreatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 144178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Chen, D.; Yang, S.; Peng, L.; Zhang, J.; Guan, Q.; Zhang, P. Deep Insights into the Atmospheric Sodium Hydroxide-Hydrogen Peroxide Extraction Process of Hemicellulose in Bagasse Pith: Technical Uncertainty, Dissolution Kinetics Behavior, and Mechanism. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 10150–10159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wang, S.; Sang, S.; Li, H. Comprehensively Understanding Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Lignocellulose and Cellulase–Lignocellulose Adsorption by Analyzing Substrates’ Physicochemical Properties. Bioenergy Res. 2020, 13, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Peng, W.; Yang, S.; Yang, C. Delignification Kinetic Modeling of NH4OH-KOH-AQ Pulping for Bagasse. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 123, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.J.; Zhai, H.M.; Lai, Y.Z. On the Chemical Aspects of the Biodelignification of Wheat Straw with Pycnoporus sanguineus and Its Combined Effects with the Presence of Candida tropicalis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 91, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Miazek, K.; Grande, P.M.; Domínguez De María, P.; Leitner, W.; Modigell, M. Mechanical Pretreatment in a Screw Press Affecting Chemical Pulping of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 6981–6987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Tabil, L.G.; Niu, C. Delignification of Intact Biomass and Cellulosic Coproduct of Acid-Catalyzed Hydrolysis. AIChE J. 2015, 61, 1783–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Bharadwaja, S.T.P.; Yadav, P.K.; Moholkar, V.S.; Goyal, A. Mechanistic Investigation in Ultrasound-Assisted (Alkaline) Delignification of Parthenium hysterophorus Biomass. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 14241–14252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, J.-P.; Yao, M.-S. Clean Production of Corn Stover Pulp Using Koh+Nh 4 Oh Solution and Its Kinetics During Delignification. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2012, 18, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, L.K.; Bansal, M.C.; Pathak, P.; Dutt, D.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, S. Kinetics of Delignification of Bast Fiber of Jute Plant (Corcorus capsularis) in Alkaline Pulping. IPPTA 2012, 4, 123–127. Available online: https://ippta.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/2012_Issue_2_IPPTA_Articel_11.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Spigno, G.; Pizzorno, T.; De Faveri, D.M. Cellulose and Hemicelluloses Recovery from Grape Stalks. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 4329–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, D.; Upadhyay, J.S.; Singh, B.; Tyagi, C.H. Studies on Hibiscus cannabinus and Hibiscus sabdariffa as an Alternative Pulp Blend for Softwood: An Optimization of Kraft Delignification Process. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 29, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Dabral, S.K.; Naithani, S.; Singh, S. V Kinetics of Delignification and Carbohydrate Dissolution during Kraft and Soda Cooking of Kenaf. IPPTA 2004, 16, 61–62. Available online: https://ippta.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/IPPTA-162-61-62-Kinetics-of-Delignification.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Correia, F.; Roy, D.N.; Goel, K. Chemistry and Delignification Kinetics of Canadian Industrial Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.). J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2001, 21, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, S.N.; Volkova, I.Y.; Zakharov, A.G. Kinetics of Alkaline Delignification of Flax Fibre. Fibre Chem. 2004, 36, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, B.; van Dam, J.E.; van’t Riet, K. Alkaline Pulping of Hemp Woody Core: Kinetic Modelling of Lignin, Xylan and Cellulose Extraction and Degradation. Holzforschung 1995, 49, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, B.; van Dam, J.E.; van der Zwan, R.P.; van’t Riet, K. Simplified Kinetic Modelling of Alkaline Delignification of Hemp Woody Core. Holzforschung 1994, 48, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Holtzapple, M.T. Delignification Kinetics of Corn Stover in Lime Pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, H.; Roy, D.N. Delignification Kinetics of Soda Pulping of Kenaf. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 1996, 16, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimlamai, B.; Choorit, W.; Chisti, Y.; Prasertsan, P. Cellulose from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch Fiber and Its Conversion to Carboxymethylcellulose. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 1656–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, J.; Fernández, N.; Peniche, C. Soda Pulping of Bagasse: Delignification Phases and Kinetics. Holzforschung 1993, 47, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, L.L.G.; Rabelo, S.C.; Filho, R.M.; Costa, A.C. Kinetics of Lime Pretreatment of Sugarcane Bagasse to Enhance Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2011, 163, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Zhao, X.; Liu, D. Kinetic Modeling of Atmospheric Formic Acid Pretreatment of Wheat Straw with “Potential Degree of Reaction” Models. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 20992–21000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yang, X.; Wan, J.; He, Y.; Chang, C.; Ma, X.; Bai, J. Delignification Kinetics of Corn Stover with Aqueous Ammonia Soaking Pretreatment. Bioresources 2016, 11, 2403–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazy, M.B. Effect of Temperature and Time on the Kraft Pulping of Egyptian Bagasse. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2016, 5, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T.; Gnanasundaram, N.; Appusamy, A.; Kait, C.F.; Thanabalan, M. Enhanced Lignin Extraction from Different Species of Oil Palm Biomass: Kinetics and Optimization of Extraction Conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 116, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiin, C.L.; Yusup, S.; Quitain, A.T.; Uemura, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Kida, T. Delignification Kinetics of Empty Fruit Bunch (EFB): A Sustainable and Green Pretreatment Approach Using Malic Acid-Based Solvents. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy 2018, 20, 1987–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Hu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wan, Y.; Ruan, R. Fractionation and Thermal Characterization of Hemicelluloses from Bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens Mazel) culm. Bioresources 2012, 7, 374–390. Available online: https://bioresources.cnr.ncsu.edu/resources/fractionation-and-thermal-characterization-of-hemicelluloses-from-bamboo-phyllostachys-pubescens-mazel-culm/ (accessed on 5 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Keshwani, D.R.; Cheng, J.J. Modeling Changes in Biomass Composition during Microwave-Based Alkali Pretreatment of Switchgrass. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 105, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatalov, A.A.; Pereira, H. Kinetics of Organosolv Delignification of Fibre Crop Arundo donax L. Ind. Crops Prod. 2005, 21, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanni, S.E.; Akinrinola, O.; Ojima Yusuf, E.; Fagbiele, O.O.; Agboola, O. Chemical Kinetics of Alkaline Pretreatment of Napier Grass (Pennisetum purpureum) Prior Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Open Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 12, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahboubi, N.; Karouach, F.; Bakraoui, M.; El Gnaoui, Y.; Essamri, A.; El Bari, H. Effect of Alkali-NaOH Pretreatment on Methane Production from Anaerobic Digestion of Date Palm Waste. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2022, 23, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, V.; Nguyen, K.L. Characterisation of the Heterogeneous Alkaline Pulping Kinetics of Hemp Woody Core. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemida, M.H.; Moustafa, H.; Mehanny, S.; Morsy, M.; Abd ELRahman, E.N.; Ibrahim, M.M. Valorization of Eichhornia Crassipes for the Production of Cellulose Nanocrystals Further Investigation of Plethoric Biobased Resource. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Li, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Jiang, G.; Cheng, T.; Bai, R.; Song, L. Cattail Fibers as Source of Cellulose to Prepare a Novel Type of Composite Aerogel Adsorbent for the Removal of Enrofloxacin in Wastewater. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 191, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salahuddin, N.; Abdelwahab, M.A.; Akelah, A.; Elnagar, M. Adsorption of Congo Red and Crystal Violet Dyes onto Cellulose Extracted from Egyptian Water Hyacinth. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 1375–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, S.; Yokoyama, T.; Akiyama, T.; Matsumoto, Y. Reactivity of Lignin with Different Composition of Aromatic Syringyl/Guaiacyl Structures and Erythro/Threo Side Chain Structures in β-O-4 Type during Alkaline Delignification: As a Basis for the Different Degradability of Hardwood and Softwood Lignin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 6471–6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.F. Molecular Theory of Delignification. Macromolecules 1981, 14, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.F.; Johnson, D.C. Delignification and Degelation: Analogy in Chemical Kinetics. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1981, 26, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxi, P.B.; Pandit, A.B. Using Cavitation for Delignification of Wood. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 110, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andérez Fernández, M.; Rissanen, J.; Pérez Nebreda, A.; Xu, C.; Willför, S.; García Serna, J.; Salmi, T.; Grénman, H. Hemicelluloses from Stone Pine, Holm Oak, and Norway Spruce with Subcritical Water Extraction—Comparative Study with Characterization and Kinetics. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 133, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusby, G.R.; Maass, O. The Delignification of Wood by Strong Alkaline Solutions. Can. J. Res. 1937, 15b, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Shuai, X.; Yang, D.; Zhou, X.; Gao, T. Kinetic Analysis of Pulping of Rice Straw with P-Toluene Sulfonic Acid. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 7787–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço, A.; Gominho, J.; Pereira, H. Modeling of Sapwood and Heartwood Delignification Kinetics of Eucalyptus globulus Using Consecutive and Simultaneous Approaches. J. Wood Sci. 2011, 57, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Zhu, X. Machine Learning Approach for the Prediction of Biomass Waste Pyrolysis Kinetics from Preliminary Analysis. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 48125–48136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Xu, H.; Li, B. Machine Learning Prediction of Delignification and Lignin Structure Regulation of Deep Eutectic Solvents Pretreatment Processes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 203, 117138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Patent Classification IPC Publication. Available online: https://ipcpub.wipo.int/?notion=scheme&version=20250101&symbol=D21B&menulang=en&lang=en&viewmode=f&fipcpc=no&showdeleted=yes&indexes=no&headings=yes¬es=yes&direction=o2n&initial=A&cwid=none&tree=no&searchmode=smart (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Paper Chemistry Inst GB1119546 Improved Method of Treating Fibrous Material. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=GB135288726&_cid=P20-MBKXM7-55216-1 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- FR2256283. Delignification of Lignocellulosic Material for Paper—With Alkali Metal Hydroxide, Oxygen and Opt. Alkali Metal Sulphide. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=FR186053108&_cid=P10-MGP3G4-69835-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- GB1434232. Method of Producing Cellulose Pulp by Means of Oxygen Gas Delignification. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=GB135617795&_cid=P10-MGP3KC-73941-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- FR2304718. Delignification with Gas Contg Oxygen in Aq Alkaline Soln—Using Water-Soluble Oxygen Carrier, Ensuring Good Oxygen Transfer. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=FR187299295&_cid=P10-MGP3RN-80563-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- US4012280. Delignification of Lignocellulosic Material with an Alkaline Liquor in the Presence of a Cyclic Keto Compound. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US36918161&_cid=P10-MGP3TW-82533-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- FR2333892. Cellulose Extraction from Vegetable Prods—By Delignification with Sodium Hydroxide Soln. Contg. e.g., Aluminium Sulphate. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=FR186895945&_cid=P10-MGP41V-90535-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- FR2353673. Alkaline Cooking, Washing and Delignification of Cellulose Shavings—For Paper Pulp in Vertical Three Zone Reactor (SW 27.12.77). Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=FR185459079&_cid=P10-MGP45I-93972-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- GB1500011. Method for the Dilignification of Lignocellulosic Materia. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=GB135684344&_cid=P10-MGP4FG-03678-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- US4087318. Oxygen-Alkali Delignification of Lignocellulosic Material in the Presence of a Manganese Compound. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US37022957&_cid=P10-MGP4HX-06185-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CA1039908. Process for the Delignification of Lignocellulosic Material. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CA93439690&_cid=P10-MGP4NH-11225-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- US4089737. Delignification of Cellulosic Material with an Alkaline Aqueous Medium Containing Oxygen Dissolved Therein. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US37025369&_cid=P10-MGP4P6-13010-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- FR2374464. Delignifying Materials to Mfr. Cellulose—Using Alkaline Pulping Liq. Contg. Cyclic Ketone and Aromatic Nitro Cpd. to Increase Yield. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=FR188303988&_cid=P10-MGP3W5-85008-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CA1043515. Method for Controlling Batch Alkaline Pulp Digestion in Combination with Continuous Alkaline Oxygen Delignification. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CA93443297&_cid=P10-MGP3Y6-86787-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- US4134787. Delignification of Lignocellulosic Material with an Alkaline Liquor Containing a Cyclic Amino Compound. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US37081442&_cid=P10-MGP4T7-16769-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CA1050212. Method of Increasing Pulp Yield and Viscosity. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CA93450001&_cid=P10-MGP4XA-20749-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- US4155806. Method for Continuous Alkaline Delignification of Lignocellulose Material in Two or More Steps, the Final of Which with Oxygen. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US37067658&_cid=P10-MGP4ZG-22913-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CA1073161. Delignification Process. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CA93472965&_cid=P10-MGP52R-25991-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- EP0010451. Process for the Delignification of Lignocellulosic Material and Products Thereof. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=EP11264495&_cid=P10-MGP54E-27596-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CA1104762. Pulping Processes. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CA93504567&_cid=P10-MGP57C-30337-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CA1110413. Process for Pulping Lignocellulosic Material. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CA93510213&_cid=P10-MGP5AM-33149-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- ES8504999. Procedimiento y Aparato para la Deslignificacion Continua por Oxigeno de Materiales Fibrosos. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=ES4846844&_cid=P10-MGP5CI-35003-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CA1190360. Catalyzed Alkaline Peroxide Delignification. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CA93590168&_cid=P10-MGP5EO-36728-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CS219091. Method of Alcalic Delignification of the Ligno-Cellulose Material in Presence of Derivatives of Antrachinone and Mixtures Thereof. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CS298344752&_cid=P10-MGP5IF-40123-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CA1153164. Process for Pulping Lignocellulosic. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CA93552968&_cid=P10-MGP5NG-44677-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- EP0095239. Delignification of Lignocellulosic Material. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=EP11439829&_cid=P10-MGP5PH-46360-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- TH121198. Method for Producing Sugars from Lignocellulosic Biomass Comprising the Step of Alcoholic-Alkaline Delignification in the Presence of HO. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=TH203182398&_cid=P10-MGP5RO-48077-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Kazimierczak, J.; Kopania, E.; Bloda, A.; Krzyżanowska, G.; Kluska, A.; Wietecha, J.; Ciechańska, D. Method of Preparing Cellulose Nano-Fibres from Stalks of Annual Plants. 2016. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2016013946A1/en (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- TH146910. Pulping Processes. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=TH203200394&_cid=P10-MGP5TQ-49817-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- EP3172378. Method of Preparing Cellulose Nano-Fibres from Stalks of Annual Plants. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=EP198048446&_cid=P10-MGP5UL-50585-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- EP3337925. A Process for Producing Cellulose with Low Impurities from Sugarcane Bagasse. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=EP222890446&_cid=P10-MGP5VH-51350-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- US20190010660. Process for Producing Cellulose with Low Impurities from Sugarcane Bagasse. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US235906447&_cid=P10-MGP5W7-51945-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CN110387767. Method for Oxidization, Cooking and Delignification of Alkaline Potassium-Containing Compound to Realize Preparation of Pulp and Coproduction of Water-Soluble Fertilizer. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN276141757&_cid=P10-MGP5WY-52693-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- RO134127. Method for Alkaline Pre-Treatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass in the Presence of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAME). Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=RO296231094&_cid=P10-MGP5XN-53332-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- RU0002763880. Method for Producing Cellulose from Miscanthus for Chemical Processing. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=RU349202182&_cid=P10-MGP652-59933-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CN117005231. Method for Improving Performance of Wheat Straw Oxygen Alkali Pulp through Biological Enzyme Composite Pretreatment. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN414612210&_cid=P10-MGP66A-61030-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CN117107539. Eucalyptus Pulp with Low Polymerization Degree as Well as Production Process and Application Thereof. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN416015274&_cid=P10-MGP679-61933-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- RU0002804999. Method for Producing Microcrystalline Cellulose from Industrial Hemp Trust. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=RU410589437&_cid=P10-MGP69H-64224-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- US20240328083. Method for Preparing Fluff Pulp from Bamboos and Fluff Pulp Prepared Thereby. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=US440278362&_cid=P10-MGP6A7-64980-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- CN118019889. Method for Producing Chemical Thermal Mechanical Fiber Pulp from Non-Woody Plant Raw Materials, and Automated Production Line for Producing Said Pulp by Said Method. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=CN429425187&_cid=P10-MGP6AZ-65727-1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Hart, P.W.; Rudie, A.W. Anthraquinone—A Review of the Rise and Fall of a Pulping Catalyst. TAPPI J. 2014, 13, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, J.; Lindström, M.E.; Vikström, T.; Esteves, C.V.; Henriksson, G.; Sevastyanova, O. Chemical Pulping on the Nature of the Selectivity of Oxygen Delignification. Nord. Pulp Paper Res. J. 2024, 40, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heiningen, A.R.P.; Ji, Y.; Jafari, V. Recent Progress on Oxygen Delignification of Softwood Kraft Pulp. Cellul. Sci. Technol. Chem. Anal. Appl. 2018, 67–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolore, R.S.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Green and Sustainable Pretreatment Methods for Cellulose Extraction from Lignocellulosic Biomass and Its Applications: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2024, 7, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justia Patents Search. Process for Treatment of Biomass for Pulping Biorefinery Applications. U.S. Patent Application #20240401270, 5 December 2024. Available online: https://patents.justia.com/patent/20240401270?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Justia Patents Search. Processes for Fractionation of Biomass. U.S. Patent Application #20250075425, 6 March 2025. Available online: https://patents.justia.com/patent/20250075425?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Qureshi, S.S.; Nizamuddin, S.; Xu, J.; Vancov, T.; Chen, C. Cellulose Nanocrystals from Agriculture and Forestry Biomass: Synthesis Methods, Characterization and Industrial Applications. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 58745–58778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta Neves, R.; Silveira Lopes, K.; Zimmermann, M.G.V.; Poletto, M.; Zattera, A.J. Cellulose Nanowhiskers Extracted from Tempo-Oxidized Curaua Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2020, 17, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenfant, G.; Heuzey, M.C.; van de Ven, T.G.M.; Carreau, P.J. Gelation of Crystalline Nanocellulose in the Presence of Hydroxyethyl Cellulose. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 95, 1891–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, G.; Skrzypczak, D.; Mironiuk, M.; Mikula, K.; Samoraj, M.; Gil, F.; Taf, R.; Moustakas, K.; Chojnacka, K. Lignocellulosic Biomass Fertilizers: Production, Characterization, and Agri-Applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

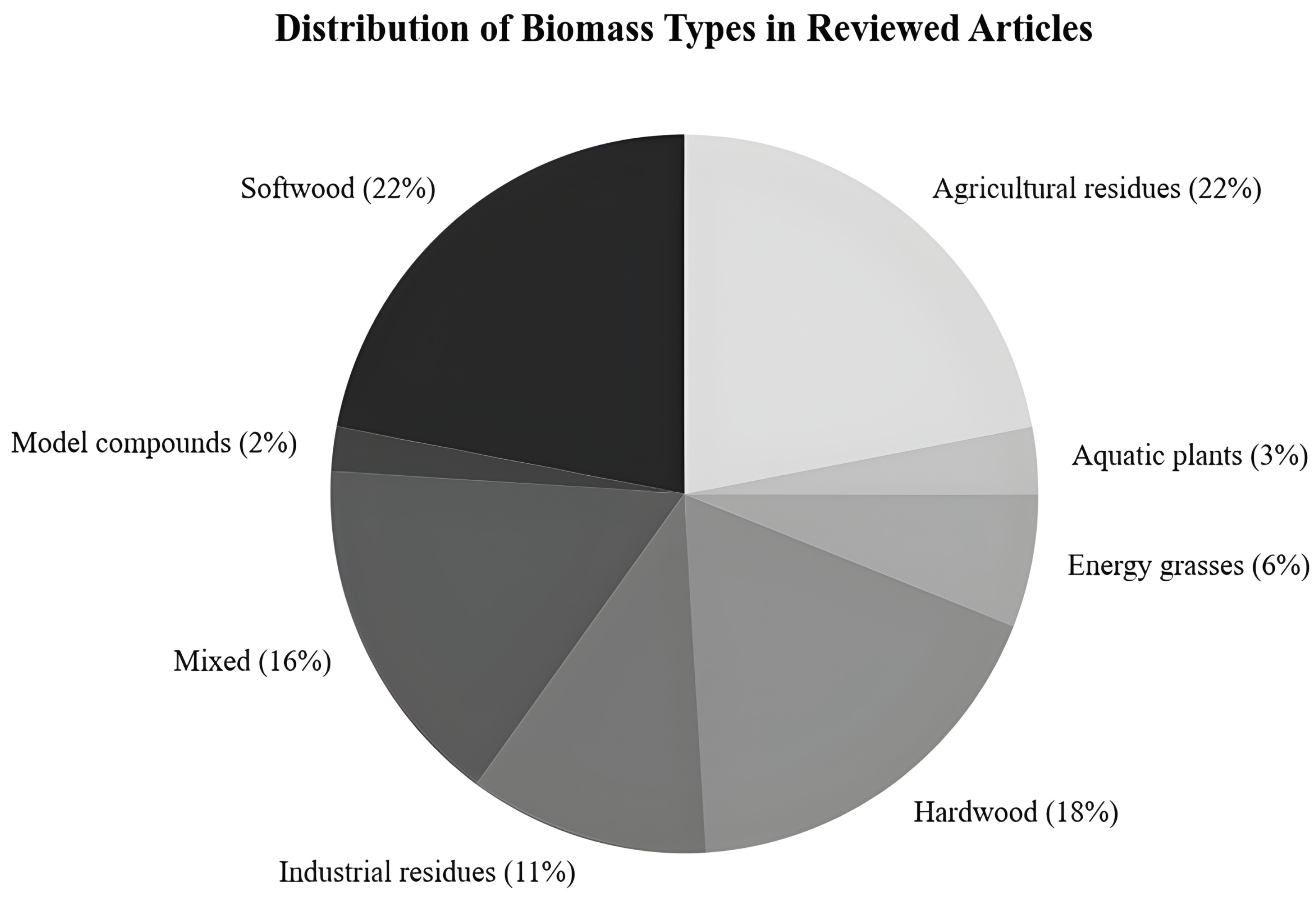

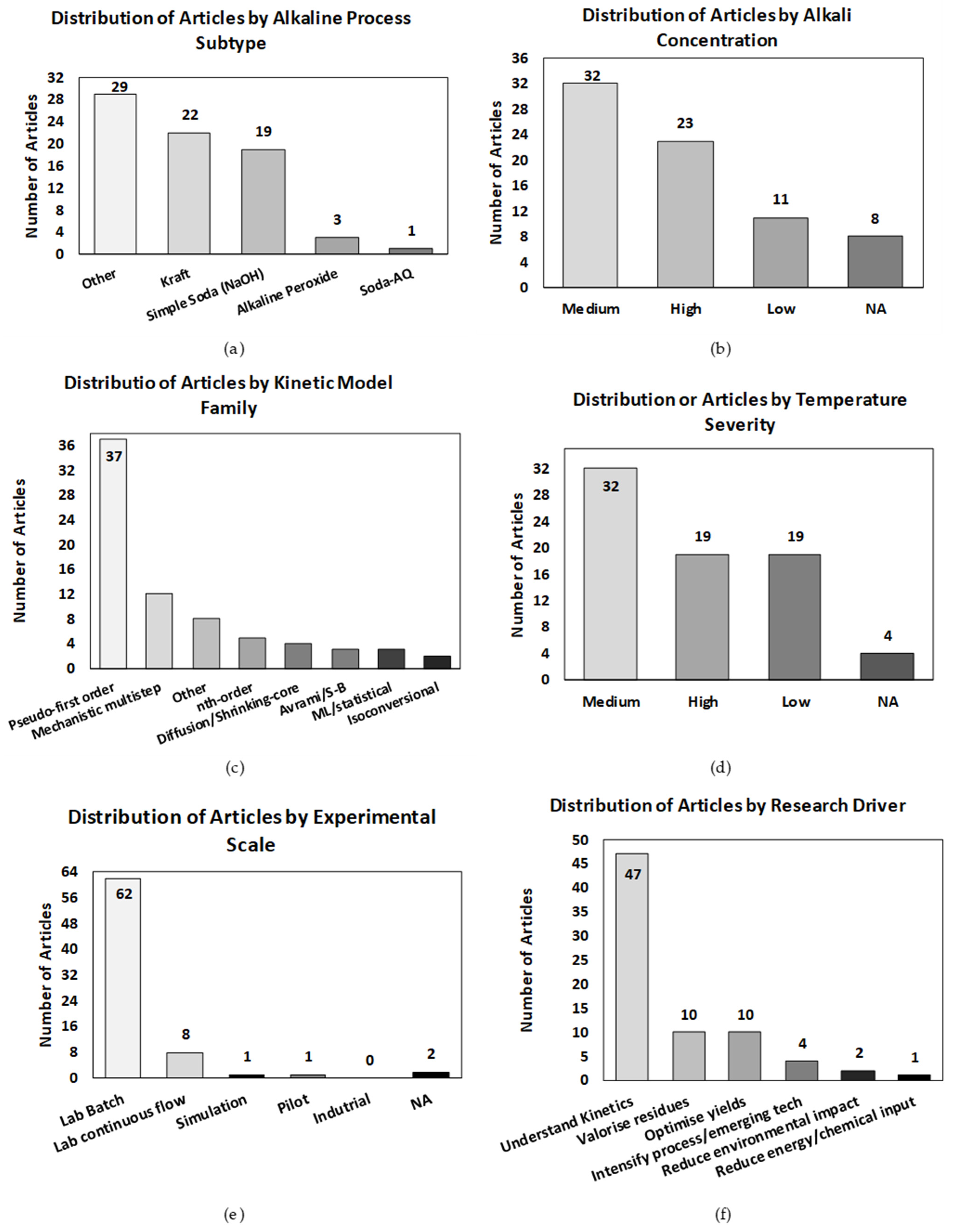

| Category | Process Variables | Definition and Criteria for Selection | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Type | Hardwood | Angiosperm woods like Eucalyptus and Populus. | [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] |

| Softwood | Gymnosperm woods like Pinus and Picea. | [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] | |

| Agricultural residues | Crop leftovers like rice straw and sugarcane bagasse. | [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] | |

| Energy grasses | Non-food dedicated crops like Miscanthus. | [61,62,63,64] | |

| Industrial residues | By-products from processes (e.g., paper sludge). | [47,49,65,66]. | |

| Aquatic plants | Lignified aquatic biomass (e.g., Typha). | [67,68,69] | |

| Model compounds | Pure components like lignin, xylan, and cellulose. | [70,71,72] | |

| Mixed | More than one biomass type with no dominant one. | [16,73,74,75] | |

| Subtype | Simple soda (NaOH) | Uses NaOH alone as active delignifying agent. | [68] |

| Soda-AQ | NaOH with anthraquinone catalyst. | [11] | |

| Kraft | NaOH + Na2S pulping (white liquor). | [6,10,12,15,16,17,21,22,23,24,25,28,29,30,33,45,46,58,71,72] | |

| Alkaline peroxide | NaOH and H2O2 under high pH. | [20,37,55] | |

| Other | Any non-listed alkali variant (e.g., DES, hybrid, Caustic extraction, O2-Alkaline, and cavitation). | [9,11,14,19,20,31,34,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44,51,55,56,57,59,60,61,62,63,65,67,70,73,74] | |

| Alkali Concentration | Low | NaOH < 2% w/w on dry biomass. | [20,36,38,40,41,43,46,62,64,66,70] |

| Medium | NaOH 2–10% w/w. | [7,8,10,11,12,13,15,16,19,20,22,23,27,29,32,35,40,47,49,50,53,54,55,56,57,58,61,65,66,69,73] | |

| High | NaOH > 10% w/w. | [6,9,12,17,21,24,25,26,27,28,30,33,37,42,43,45,46,47,48,52,63,70,75] | |

| Kinetic Modeling | Conventional | Pseudo-first order | [6,10,14,18,21,22,24,25,28,29,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,47,48,49,50,51,52,55,56,57,58,60,61,63,67,70,74] |

| Pseudo-second-order | [70] | ||

| Zero-order | [48] | ||

| Third-order | [75] | ||

| nth-order | [11,21,44,56,66] | ||

| Power-law | [13] | ||

| Non-conventional | Avrami/Š–B: Avrami, Šesták–Berggren solid state models. | [15,16,66] | |

| Diffusion/Shrinking core: Models involving diffusion or contracting geometry. | [14,25,33] | ||

| Mechanistic multistep: Stepwise reactions (e.g., peeling, depolymerization). | [9,13,16,17,30,33,35,37,49,62,71] | ||

| Isoconversional: Model-free methods: Friedman, OFW, KAS. | [34,38] | ||

| ML/statistical: Machine learning or statistical based prediction. | [61,67,71] | ||

| Temperature | Low | T < 120 °C | [6,20,30,33,36,41,48,51,53,55,56,57,59,60,65,67,68,69,73] |

| Medium | 120–160 °C | [7,11,12,13,14,15,16,23,25,27,29,31,32,34,35,38,39,40,43,44,47,49,50,54,58,62,63,64,66,74,75] | |

| High | >160 °C | [8,9,10,16,17,19,21,22,24,26,28,37,42,45,46,47,52,61,70] | |

| Experimental Scale | Lab batch | Batch system < 5 L. | [8,9,10,11,12,14,16,18,20,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,66,67,69,70,71,72,75,76,77] |

| Lab continuous flow | Continuous, small-scale tubular/CSTR reactor. | [11,13,15,20,49,50] | |

| Pilot | Throughput in 10 kg/h–1 t/h range. | [41] | |

| Industrial | Full-scale operational system. | ||

| N/A (simulation) | No experiment, only simulation/modeling. | [17,71,72] | |

| Research Driver | Optimize yields | Improve delignification or carbohydrate recovery. | [6,7,43,46,47,49,53,55,65] |

| Understand kinetics | Mechanistic insight or model development. | [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,33,35,36,37,38,40,48,50,51,52,54,56,57,58,62,63,64,66,70,71,72,74,75] | |

| Valorize residues | Waste-to-value strategies using lignocellulose. | [32,34,42,44,45,59,61,67,68,69] | |

| Reduce environmental impact | Emissions, LCA, circularity focus. | [21,47,60] | |

| Intensify process/ emerging tech | New configurations or process intensification. | [31,39,41,73] |

| Biomass | Pulping Process | Conditions | Model Used | Ea (kJ mol−1) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western hemlock | Kraft, Soda, Soda-AQ | 80–150 °C t ≤ 10 h | Non-first-order Pseudo-first-order | 50 | [25] |

| 73 | |||||

| Alkaline pulping | 150–180 °C t ≤ 720 min | Three-phase exponential model | 30 | [15] | |

| 31.6 | |||||

| 26.3 | |||||

| Bagasse | Soda pulping | 150–180 °C | Pseudo-first-order | 66.3 | [56] |

| 49.4 | |||||

| 93.5 | |||||

| Hemp | Alkaline pulping | 150–180 °C t ≤ 240 min | Two simultaneous first order | 143.6 | [52] |

| 172.8 | |||||

| Hemp | Alkaline pulping | 150–180 °C t ≤ 210 min | First-order | 127 | [51] |

| 108.9 | |||||

| Kenaf | Soda pulping | 140–170 °C t ≤ 150 min | First-order | 68 | [54] |

| 91 | |||||

| 75 | |||||

| Eucalyptus globulus | Kraft pulping | 100–180 °C | Three-stage model | 40 | [14] |

| 105 | |||||

| Hemp | Soda pulping | 140–170 °C t = 30–210 min | First-order | 41 | [49] |

| 76 | |||||

| 76 | |||||

| Flax fiber | Soda pulping | 47–87 °C t ≤ 120 min | First-order | 47.1 | [50] |

| Arundo donax L. | alkali organosolv pulping | 130–150 °C t ≤ 360 min | Three-parallel first-order model | 64.6 | [65] |

| 89.1 | |||||

| 96.0 | |||||

| Pinus pinaster | Kraft pulping | 160–180 °C 5–150 min | Three-phase first-order model | 90.0 | [26] |

| 68.3 | |||||

| Corn stover | Lime pretreatment | 25–55 °C | Three-phase first-order model | 50.15 | [53] |

| 54.21 | |||||

| Eucalyptus nitens | Kraft pulping | 130–165 °C t = 30–300 min | Fractal/Avrami model | 97.3 | [17] |

| Southern pine | Alkaline oxygen delignification | T ≤ 90 °C 75 psig | First-order | 53 | [22] |

| Kenaf | Kraft pulping | 160 °C t = 120 min | First-order | 93.88 | [47] |

| 78.50 | |||||

| Bagasse | Lime pretreatment | 60–90 °C t = 24–108 h | First-order | 31.47 | [57] |

| Biomass | Pulping Process | Conditions | Model Used | Ea (kJ mol−1) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birch wood (Betula pendula) | Kraft pulping | 130–170 °C t = 3.5–1320 min | Parallel pseudo-first-order | 112.9 | [12] |

| Corn stover | Alkaline pulping | 150 °C 30 min | Pseudo-first-order | 23 | [82] |

| Corchorus capsularis | Alkaline pulping | 90–110 °C t ≤ 180 min | First-order | 30.5 | [45] |

| Acacia nilotica | Alkaline catalytic pulping | 100–140 °C 1–3 h | Fractal kinetic model (modified Nuclei Growth) | 20.93 | [10] |

| 35.0 | |||||

| Pinus sylvestris | Oxygen delignification | 95–105 °C t = 5–90 min | Power-law | 47 | [21] |

| 63 | |||||

| Wheat straw | Organosolv | 70–107 °C t ≤ 2 h | First-order | 43.83 | [58] |

| Corn stover | Soaking aqueous ammonia (SAA) | 30–70 °C t = 1–48 h | Three-phase first-order model | 61.05 | [59] |

| 59.46 | |||||

| Bagasse | Kraft pulping | 140–180 °C t = 30–150 min | First-order | 36.8 | [60] |

| 25.3 | |||||

| Wheat straw | Alkaline pulping | 60–90 °C t = 10–100 min | Pseudo-first-order | 67.9 | [16] |

| EFB PMF PKS | [PyFor] organosolv pretreatment | 50–100 °C; 60–300 min | Pseudo-second order | 12 | [61] |

| 23 | |||||

| 28 | |||||

| EFB | Malic acid-based LTTM | 60–100 °C t = 6–24 h | Three-stage first-order model | 36–56 | [62] |

| 34–90 | |||||

| 19–26 | |||||

| 47–87 | |||||

| Bagasse | Alkaline pulping | 165 °C t ≤ 200 min | Three-phase kinetic model | 45.29 | [39] |

| Pine & Deodar sawdust | Alkaline peroxide | 30–100 °C t ≤ 5 h | Pseudo-first-order model | 17.87 + 18.71 | [20] |

| Douglas fir softwood | Kraft pulping | 130 °C t = 7–46 h | Pseudo-first-order | Not specified | [27] |

| Hemp | Kraft pulping | 105 °C t = 45 min | Mechanistic multistep | 66.8 | [32] |

| IPC Code | Specific IPC Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| D21C | D21C 1/06 | Alkaline pretreatments (e.g., NaOH) |

| D21C 3/02 | Alkaline pulping with inorganic bases | |

| D21C 3/22 | Enhancements to pulping operations | |

| D21C 3/26 | Multi-stage delignification processes | |

| D21H | D21H 11/04 | Kraft or sulfate pulps |

| D21H 11/20 | Chemically/biochemically modified fibers | |

| D21H 17/23 | Processes targeting lignin | |

| D21H 17/24 | Processes targeting polysaccharides | |

| D21H 17/64 | Use of alkaline compounds | |

| D21H 23/04 | Addition of chemicals to pulp | |

| D21H 23/08 | In-process measurements | |

| D21H 23/16 | Additives during refining | |

| C12P | C12P 7/08 | Ethanol from waste/cellulosic material |

| C12P 7/10 | Ethanol from lignocellulosic substrates | |

| C12P 7/12 | Processing sulfite liquor/citrus waste | |

| C08B | C08B 1/00 | Cellulose pretreatment |

| C08B 1/08 | Formation of alkali cellulose | |

| C08B 1/10 | Apparatus for alkali cellulose | |

| B27K | B27K 3/02 | General impregnation |

| B27K 3/08 | Pressure-based impregnation | |

| B27K 3/20 | Use of alkali/ammonium compounds | |

| B27K 5/04 | Bleaching/impregnating and drying | |

| C02F | C02F 1/52 | Flocculation/precipitation |

| C02F 1/66 | pH adjustment/neutralization | |

| C02F 3/28 | Anaerobic digestion | |

| C02F 9/00 | Multistage treatment systems | |

| C02F 103/28 | Paper/cellulose wastewater | |

| C02F 11/04 | Anaerobic sludge treatment | |

| C02F 11/14 | Chemical sludge treatment | |

| C02F 101/30 | Treatment of organic-contaminated water | |

| A23K | A23K 10/12 | Fermentation of vegetable biomass |

| A23K 10/32 | Feed from wood/straw hydrolysates | |

| A23K 10/37 | Feed from waste biomass | |

| A23L | A23L 33/21 | Indigestible substances (dietary fibers) |

| A23L 33/22 | Comminuted fibrous plant parts | |

| A23L 33/24 | Cellulose/derivatives as additives | |

| D21B | D21B 1/16 | Chemical disintegration of fibers |

| D21D | D21D 1/20 | Fiber refining |

| D21D 1/28 | Ball mills | |

| D21D 1/30 | Disk mills | |

| D21D 1/32 | Hammer mills | |

| D21D 1/40 | Fiber washing | |

| D21D 5/00–5/24 | Mechanical purification |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bustillo-Maury, J.; Nouar, A.; Aldana, A.; Mendoza-Fandiño, J.M.; Bula, A. A Review of Lignocellulosic Biomass Alkaline Delignification: Feedstock Classification, Process Types, Modeling Approaches, and Applications. Processes 2025, 13, 4038. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124038

Bustillo-Maury J, Nouar A, Aldana A, Mendoza-Fandiño JM, Bula A. A Review of Lignocellulosic Biomass Alkaline Delignification: Feedstock Classification, Process Types, Modeling Approaches, and Applications. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4038. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124038

Chicago/Turabian StyleBustillo-Maury, Johnnys, Alma Nouar, Andres Aldana, J. M. Mendoza-Fandiño, and Antonio Bula. 2025. "A Review of Lignocellulosic Biomass Alkaline Delignification: Feedstock Classification, Process Types, Modeling Approaches, and Applications" Processes 13, no. 12: 4038. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124038

APA StyleBustillo-Maury, J., Nouar, A., Aldana, A., Mendoza-Fandiño, J. M., & Bula, A. (2025). A Review of Lignocellulosic Biomass Alkaline Delignification: Feedstock Classification, Process Types, Modeling Approaches, and Applications. Processes, 13(12), 4038. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124038