Performance Optimization of Solar-Air Source Heat Pump Heating System for Rural Residences in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Building Model and Heating Load

2.1. Building Parameters

2.2. Climate Parameters

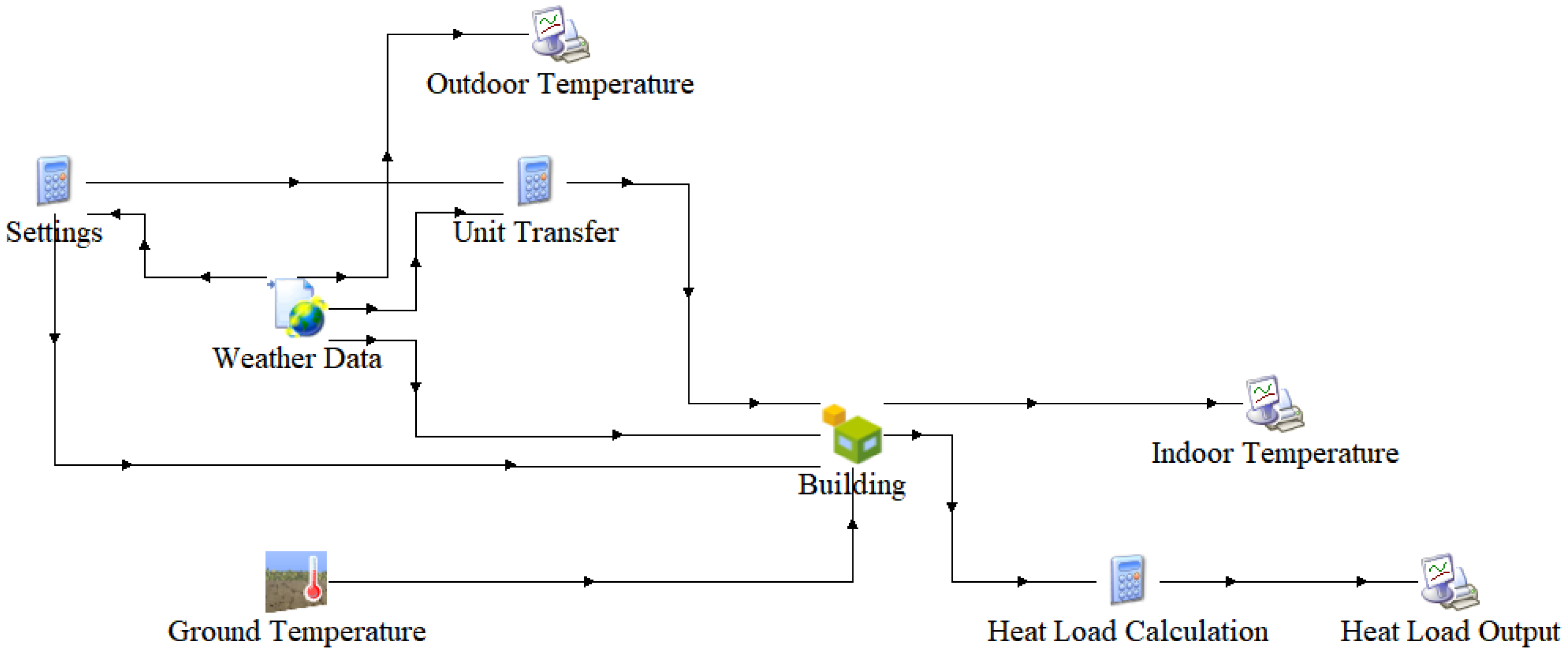

2.3. Heating Load

3. Design Scheme of the SASHP Heating System

3.1. SASHP System Model

- (1)

- The model’s core operation revolves around the thermal storage tank (Type158), which acts as the central hub for heat collection, storage, and delivery. The system operates based on the following logic and interconnections:

- (2)

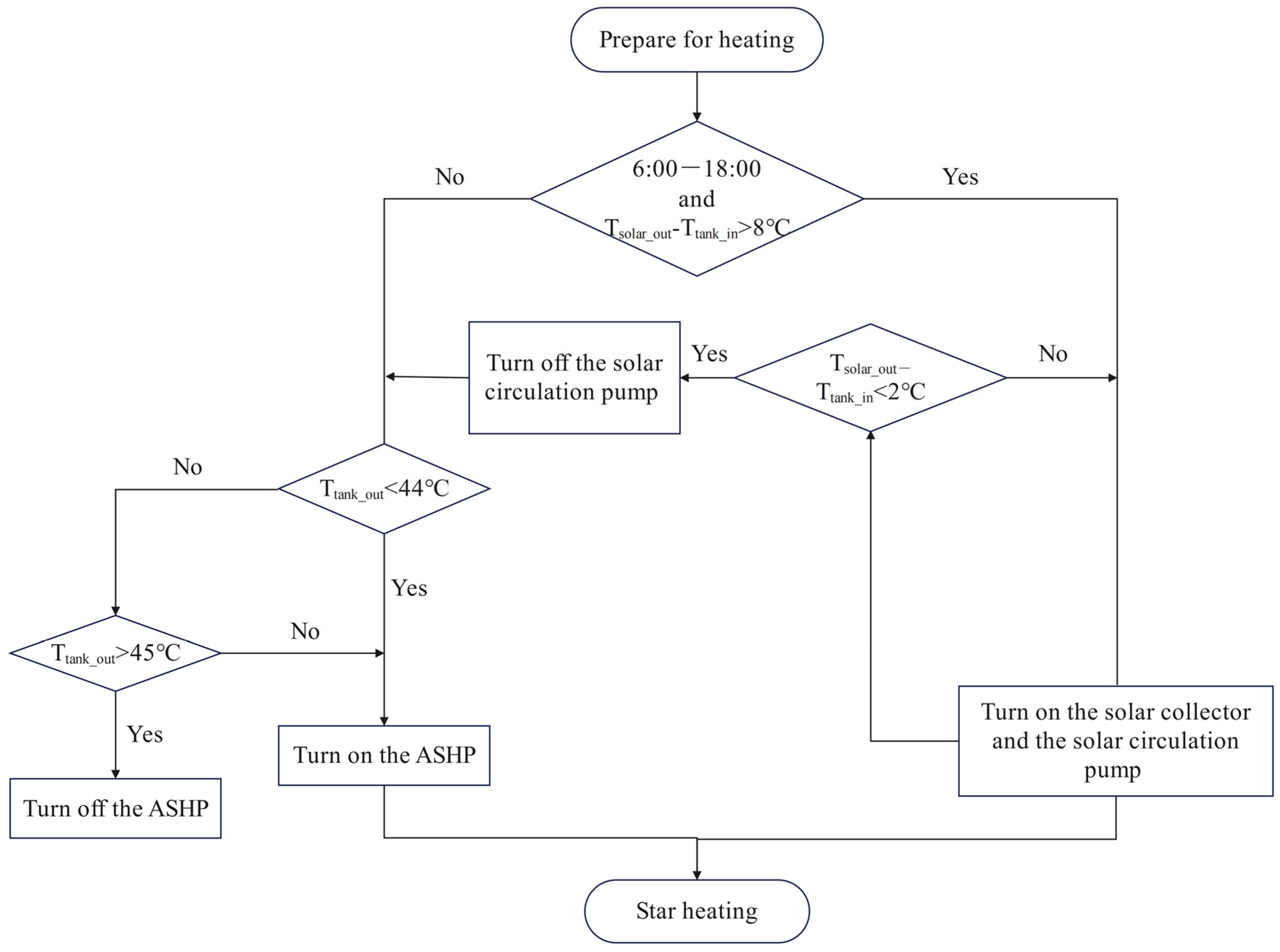

- Solar collection loop: Meteorological data (Type15-2) provides solar irradiance and ambient temperature inputs to the solar collector (Type1b). A pump (Type114) circulates the heat transfer fluid between the collector and the storage tank. This pump is activated by a differential controller (Type2b) that compares the temperature at the collector outlet with the temperature at the bottom of the storage tank. The pump operates when this temperature difference exceeds a set-point (Tsolar − Ttank > 8 °C) and stops when it falls below a lower set-point (Tsolar − Ttank < 2 °C).

- (3)

- ASHP loop: The air source heat pump (Type941) uses ambient air as its heat source. It is activated to charge the thermal storage tank based on the tank’s temperature. A controller (Type2b) monitors the temperature at the top of the storage tank. If the tank temperature drops below a set minimum (44 °C) during the heating period and solar energy is insufficient, the ASHP and its associated circulation pump are activated. The ASHP heats the water circulating through its internal condenser, which is then delivered to the storage tank. If the tank temperature increases up to a set minimum (45 °C), the ASHP and its associated circulation pump are deactivated.

- (4)

- Heating delivery loop: A third pump circulates hot water from the top of the storage tank to the heating terminal (Type682), which represents the building’s hydraulic heating system (e.g., floor heating or radiators). The heating demand calculated by the separate building model (see Section 2) is fed to this component. The return water from the heating terminal flows back to the bottom of the storage tank, completing the circuit.

3.2. Control Strategy for the SASHP System

3.3. Design Parameter Calculations for Equipment Selection

3.3.1. Solar Collector

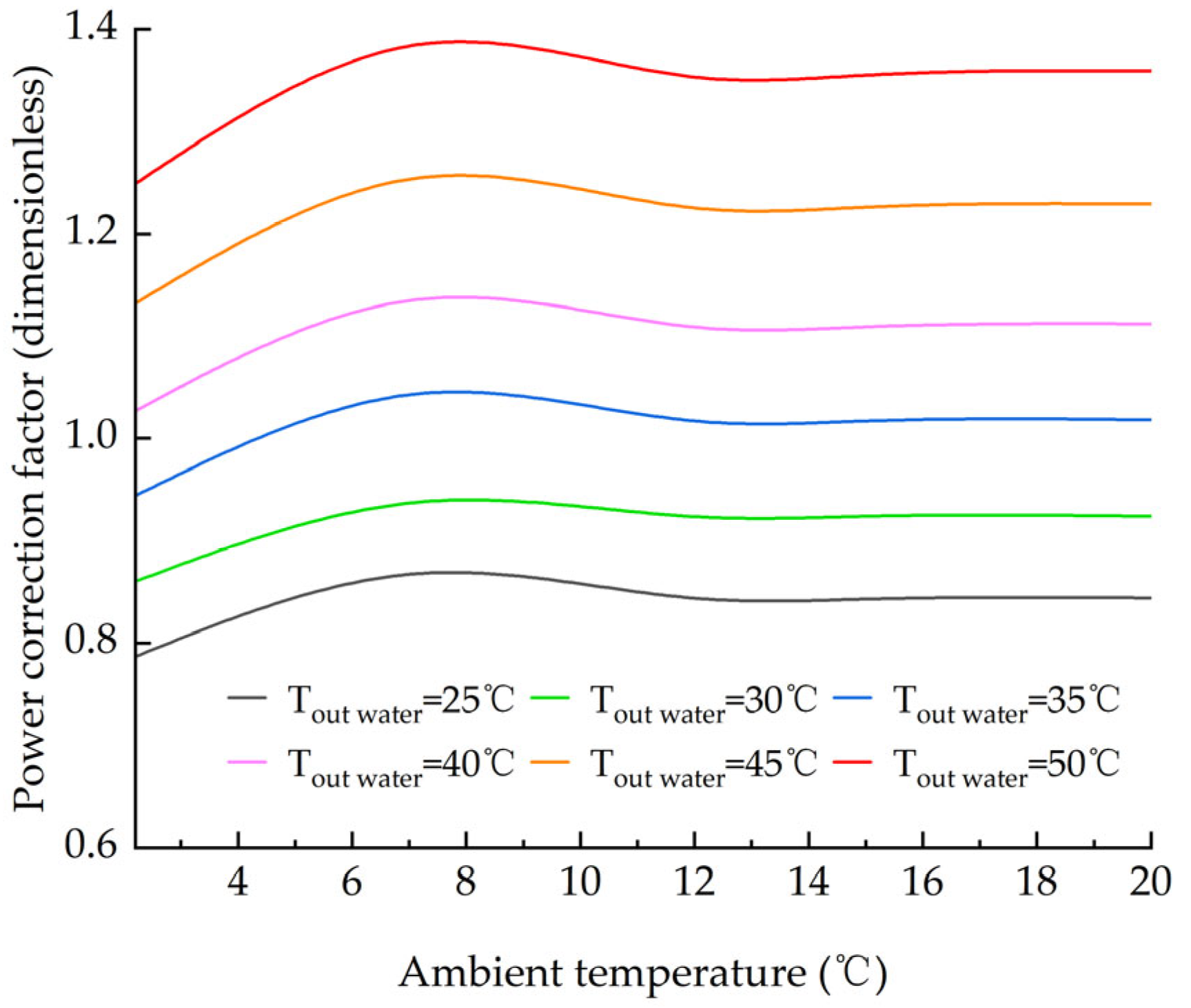

3.3.2. Nominal Heating Capacity of ASHP

3.3.3. Thermal Storage Tank Volume

3.3.4. Solar Collector-Side Pump Flow Rate

3.3.5. ASHP-Side Pump Flow Rate

3.3.6. Pump Power

3.4. Design Scheme Results

3.4.1. Supply and Return Water Temperatures

3.4.2. Energy Consumption Analysis

3.4.3. Thermal Comfort

- Category A (high comfort): PPD ≤ 6%, PMV between −0.2 and +0.2.

- Category B (medium comfort): PPD ≤ 10%, PMV between −0.5 and +0.5.

- Category C (moderate comfort): PPD ≤ 15%, PMV between −0.7 and +0.7.

4. Optimization of the SASHP System

4.1. Optimizing Configurations

4.2. Optimized Results

- (1)

- A noteworthy phenomenon observed post-optimization is that while the ASHP’s rated heating capacity decreased, its COP increased slightly. This can be attributed to two synergistic effects. On one hand, adjustments to the collector area resulted in increased ASHP operation during daytime hours in cold weather. Higher ambient temperatures improved its operating conditions, leading to occasional gains in COP. On the other hand, ASHPs with smaller capacity are compelled to operate at higher load ratios, reducing compressor start–stop cycles and inefficient low-load operation. Generally, higher part-load ratios contribute to improved average operational efficiency of the compressor.

- (2)

- In contrast to the improvement in component performance, the overall COP of the integrated heating system decreased significantly by 20.89%. This quantitative result clearly highlights the balance between economic improvement and energy efficiency. The fundamental reason for this is that the substantially reduced collector area limits the system’s ability to utilize free solar energy effectively, necessitating greater energy input from electrical equipment (primarily the ASHP), thereby reducing the system’s overall energy efficiency.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The average building heat load during the heating season in Hangzhou is 3.38 kW, with a maximum of 5.9 kW.

- (2)

- In this design scheme, the supply and return water temperatures are generally within the range of 45/35 °C. The cumulative total energy consumption of all equipment is 1354.01 kWh. The COP of the air source heat pump is 2.43, while the COP of the system is 3.67. Furthermore, the thermal comfort calculation is based on the center point of the room, and the results show that the room is in a C-level thermal comfort state. This 51% improvement in overall system efficiency not only validates the integration methodology but also indicates reduced grid dependency during operation while ensuring consistent comfort.

- (3)

- After optimization, the 35.60% reduction in initial investment brings the system within reach of rural households, while the 32.68% reduction in AEC particularly enhances long-term affordability. These improvements directly address the primary barrier of economic accessibility, transforming the SASHP system from a technical possibility into a financially viable solution for rural households, providing a quantitative decision-making basis for such trade-offs, representing a crucial pathway in renewable heating technology adoption for rural areas.

- (4)

- This study demonstrates a clear return on investment through lower annual operating costs. Thus, the significant reduction in initial investment (35.60%) after optimization becomes a key driver for promotion. Accordingly, further uptake can be accelerated through targeted government subsidies or low-interest green loans aimed at covering the upfront capital cost of renewable heating systems for rural households.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASHP | Air source heat pump |

| SASHP | Solar–air source heat pump |

| AEC | Annual equivalent cost |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| HSCW | Hot summer and cold winter |

References

- China. Statement at the General Debate of the 76th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. The 76th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. 2021, New York, USA, 22th September 2021. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202109/22/WS614a8126a310cdd39bc6a935.html (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- China. Statement at the General Debate of the 79th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. The 79th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. 2024, New York, USA, 29th September 2024. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA5NzE1MDQyOA==&mid=2651911812&idx=6&sn=7e5547bb3f62a34c58716e674a97de9b&chksm=8a184e7b527e1e79fe328641ca912602c0fe636db40e762e6c85bc36159b9dc54f68cdec48bd&scene=27 (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Li, T.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Li, G.; Mao, Q. A comprehensive comparison study on household solar-assisted heating system performance in the hot summer and cold winter zone in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50378-2019; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Assessment Standard for Green Building. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Qu, M.; Sang, X.; Yan, X.; Huang, P.; Zhang, B.; Bai, X. A simulation study on the heating characteristics of residential buildings using intermittent heating in hot-summer/cold-winter areas of China. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 241, 122360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cheng, Y.; Kosonen, R.; Jokisalo, J.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Li, B. Demand response control of heating system in office building based on adapted neutral temperature in hot summer and cold winter climate zone of China. Energy 2025, 332, 137156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ouyang, Q. Investigation of winter indoor thermal environment and heating demand of urban residential buildings in China’s hot summer—Cold winter climate region. Build. Environ. 2016, 101, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Cai, W.; Ding, C.; Xie, Y. Heating demand with heterogeneity in residential households in the hot summer and cold winter climate zone in China—A quantile regression approach. Energy 2022, 247, 123462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, J.; Cheng, Y. Study on the heating modes in the hot summer and cold winter region in China. Procedia Eng. 2015, 121, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Lu, J.; Gong, Q.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Fukuda, H. Measuring effects of insulation renewal on heating energy and indoor thermal environment in urban residence of hot-summer/cold-winter region, China. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 61, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Energy Efficiency Research Center of Tsinghua University. 2024 Annual Report on the Development Research of Building Energy Efficiency in China (Special Topic: Rural Residential Buildings); China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2024; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Østergaard, P.A.; Wen, W.; Zhou, P. Heating transition in the hot summer and cold winter zone of China: District heating or individual heating? Energy 2024, 290, 130283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yao, R.; Han, S.; Du, C.; Yu, W.; Chen, S.; Li, B.; Yu, H.; Li, N.; Peng, J.; et al. How do urban residents use energy for winter heating at home? A large-scale survey in the hot summer and cold winter climate zone in the Yangtze river region. Energy Build. 2020, 223, 110131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, X. Energy flexibility for heating and cooling in traditional Chinese dwellings based on adaptive thermal comfort: A case study in Nanjing. Build. Environ. 2020, 179, 106952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Chong, W.T.; Mohd Khairuddin, A.S.; Tey, K.S.; Wei, Y.; Han, D.; Wu, J.; Pan, S. Bi-objective optimization of a solar-assisted biogas and air-source heat pump system for rural heating applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 280, 128164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yan, D.; Guo, S.; Cui, Y.; Dong, B. A survey on energy consumption and energy usage behavior of households and residential building in urban China. Energy Build. 2017, 148, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschopp, D.; Tian, Z.; Berberich, M.; Fan, J.; Perers, B.; Furbo, S. Large-scale solar thermal systems in leading countries: A review and comparative study of Denmark, China, Germany and Austria. Appl. Energy 2020, 270, 114997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xi, J.; Cai, J.; Gu, Z. Trnsys simulation study of the operational energy characteristics of a hot water supply system for the integrated design of solar coupled air source heat pumps. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Wu, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, Z.; Shi, W.; Lin, B. Intermittent heating performance of different terminals in hot summer and cold winter zone in China based on field test. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 102546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, N. Energy, emissions, economic analysis of air-source heat pump with radiant heating system in hot-summer and cold-winter zone in China. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 70, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, S.; Yari, M.; Rosen, M.A. Exergoeconomic comparison of solar-assisted absorption heat pumps, solar heaters and gas boiler systems for district heating in Sarein town, Iran. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 153, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, K.; Fan, X.; Cheng, H.; Xu, G.; Suo, H. Effect of seawater ageing with different temperatures and concentrations on static/dynamic mechanical properties of carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2019, 173, 106910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xi, J.; Cai, J.; Gu, Z. The optimization and energy efficiency analysis of a multi-tank solar-assisted air source heat pump water heating system. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 48, 102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ding, C.; Zhou, M.; Cai, W.; Ma, X.; Yuan, J. Assessment of space heating consumption efficiency based on a household survey in the hot summer and cold winter climate zone in China. Energy 2023, 274, 127381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.W.; Xu, R.J.; Hua, N.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, W.B.; Yang, T.; Belyayev, Y.; Wang, H.S. Review of the advances in solar-assisted air source heat pumps for the domestic sector. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 247, 114710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Huang, F.; Duanmu, L.; Zhu, C.; Zheng, H.; Li, P.; Cui, Y.; Li, H.; Du, Z. Performance analysis of solar-air source heat pump heating system coupled with sand-based thermal storage floor in rural inner Mongolia, China. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 68, 105886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, F.; Liu, H. A novel dynamic operation method for solar assisted air source heat pump systems: Optimization control and performance analysis. Energy 2025, 316, 134535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; E, C.; Huang, K.; Feng, G.; Li, X.; Cui, Y. Research on Solar-Air Source Heat Pump Coupled Heating System Based on Heat Network in Severe Cold Regions of China. Energy Built Environ. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; An, L.; Wang, L.; Hou, Z.; Zhao, S.; Liu, B.; Guo, Y. Proposal and performance evaluation of a solar hybrid heat pump with integrated air-source compression cycle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, L.; Guo, S.; Yue, Q.; Sun, X.; Shi, H. Combined solar air source heat pump and ground pipe heating system for Chinese assembled solar greenhouses in gobi desert region. Processes 2025, 13, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Quan, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z. Performance and optimization of a novel solar-air source heat pump building energy supply system with energy storage. Appl. Energy 2022, 324, 119706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE Technical Committees. 2025 ASHARE Handbook-Fundamentals, SI ed.; ASHRAE Georgia: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- DB33/1015-2021; Energy Efficiency Design Standards for Residential Buildings in Zhejiang Province. Zhejiang Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development: Hangzhou, China, 2021.

- GB/T 50785-2012; Evaluation Standards for Indoor Thermal Environment of Civil Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB 55015-2021; General Code for Building Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Utilization. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- China Architecture Design & Research Group. Unified Technical Measures for Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning Design in Civil Buildings 2022; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- GB 50495-2019; Technical Code for Solar Heating Systems of Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Lu, Y. Practical Handbook for Heating and Air-Conditioning Design, 2nd ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2008; pp. 2347–2356. [Google Scholar]

- GB 50736-2012; Design Code for Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning of Civil Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Zhang, F.; Cai, J.; Ji, J.; Han, K.; Ke, W. Experimental investigation on the heating and cooling performance of a solar air composite heat source heat pump. Renew. Energy 2020, 161, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 18049-2017/ISO 7730:2005; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

| Enclosure Type | Composition | Heat Transfer Coefficient W/(m2·K) | Limit Value of Heat Transfer Coefficient W/(m2·K) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction Material | Thickness (mm) | |||

| External wall | Cement mortar | 20 | 0.467 | 0.5 |

| Steel-reinforced concrete | 165 | |||

| Extruded polystyrene foam board | 55 | |||

| Cement mortar | 20 | |||

| Roof | Cement mortar | 20 | 0.196 | 0.2 |

| Extruded polystyrene foam board | 75 | |||

| Steel-reinforced concrete | 80 | |||

| Extruded polystyrene foam board | 70 | |||

| Cement mortar | 20 | |||

| External window | Broken bridge aluminum window | 1.690 | 1.8 | |

| Floor | Cement mortar | 20 | 0.755 | - |

| Aerated concrete | 200 | |||

| Cement mortar | 20 | |||

| Module Name | Type | Quantity | Module Name | Type | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meteorological data | Type15-2 | 1 | Controller | Type2b | 2 |

| Flat plate solar collector | Type1b | 1 | Data reader | Type9e | 1 |

| ASHP | Type941 | 1 | Calculator | Equation | 6 |

| Thermal storage tank | Type158 | 1 | Integrator | Type24 | 2 |

| Pump | Type114 | 3 | Printer | Type65c | 3 |

| Converging tee | Type11h | 1 | Integral printer | Type28b | 1 |

| Diverging tee | Type11f | 1 | Scheduler | Type14h | 2 |

| Heating terminal | Type682 | 1 | Optimizer | TRNOPT | 1 |

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Collector area (Ac) | 38.63 | m2 |

| Tilt angle of collector | 40°15′ (40.25°) | - |

| ASHP rated capacity (Qhp) | 11 | kW |

| ASHP rated power | 2.72 | kW |

| Thermal storage tank volume | 1.16 | m3 |

| Solar collector pump flow rate | 1391 | kg/h |

| ASHP flow rate | 945 | kg/h |

| Location | System | Performance | Economic Analysis | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shenyang | Solar-air source heat pump coupled heating system based on heat grid | COPsys = 6.274 | The economic benefit analysis neglects to factor in the initial investment costs. | [28] |

| Chifeng | Solar-air source heat pump coupled with sand-base thermal storage | COPsys = 2.6 | Optimizing the operational mode according to local electricity pricing policies can minimize the operating costs. | [26] |

| Hefei | Solar-air composite heat source heat pump system | COPsys = 2.87~3.8 | / | [40] |

| Gobi Desert region | Solar air source heat pump technology with underground pipe systems | The average COPs during daytime and nighttime are 4.33 and 4.8, respectively. | The system can recover its costs within four years | [30] |

| Zhengzhou, Beijing, Shenyang, Wuhan, | Solar hybrid heat pump with integrated air-source compression cycle | COPsys = 3.45~4.24 in typical cities. | Annual operation cost and the life cycle cost are compared. The longer the life cycle, the better the economy of the system. | [29] |

| Zibo | PVT integrated heat pump systems and ice-tank | COPsys = 3.02 | The payback period is 3.86 years. | [31] |

| Equipment | Unit Price |

|---|---|

| ASHP | CHP = 1000 CNY/kW |

| Solar collector | CSC = 300 CNY/m2 |

| Heat storage water tank | CST = 600 CNY/m3 |

| Water pumps and other equipment | CFJ = 20% of the total price of the above three devices |

| Period of Time | Electricity Price (CNY/kWh) |

|---|---|

| 8:00–22:00 | 0.568 |

| 22:00–8:00 (the next day) | 0.288 |

| Parameter | Collector Area (m2) | Tilt of Collector (°) | Rated Heat Capacity of ASHP (kW) | Water Tank Volume Per Unit Heat Collection Area (m3/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial value | 38.63 | 40.25 | 11.00 | 0.20 |

| Minimum value | 15.00 | 20.00 | 5.00 | 0.02 |

| Maximum value | 80.00 | 80.00 | 13.00 | 0.60 |

| Iterative step | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Algorithms | HJ | PSO | HGO |

|---|---|---|---|

| AEC (CNY) | 2033.89 | 2030.57 | 2029.53 |

| Parameter | Collector Area (m2) | Tilt Angle of Collector (°) | Rated Heat Capacity of ASHP (kW) | Water Tank Volume (m3) | C0 | AEC (CNY/Year) | Average COP of ASHP | COP of System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before optimization | 38.63 | 40.25 | 11.00 | 1.16 | 24,245.00 | 3014.73 | 2.4263 | 3.6723 |

| After optimization | 15.00 | 40.75 | 10.16 | 0.35 | 15,613.00 | 2029.53 | 2.4298 | 2.9273 |

| Changing ratio | −61.17% | 1.24% | −7.64% | −69.82% | −35.60% | −32.68% | 1.44% | −20.89% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geng, Y.; Feng, L. Performance Optimization of Solar-Air Source Heat Pump Heating System for Rural Residences in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone. Processes 2025, 13, 4039. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124039

Geng Y, Feng L. Performance Optimization of Solar-Air Source Heat Pump Heating System for Rural Residences in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4039. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124039

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeng, Yanhui, and Lianyuan Feng. 2025. "Performance Optimization of Solar-Air Source Heat Pump Heating System for Rural Residences in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone" Processes 13, no. 12: 4039. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124039

APA StyleGeng, Y., & Feng, L. (2025). Performance Optimization of Solar-Air Source Heat Pump Heating System for Rural Residences in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone. Processes, 13(12), 4039. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124039