Spirulina-Incorporated Biopolymer Films for Antioxidant Food Packaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

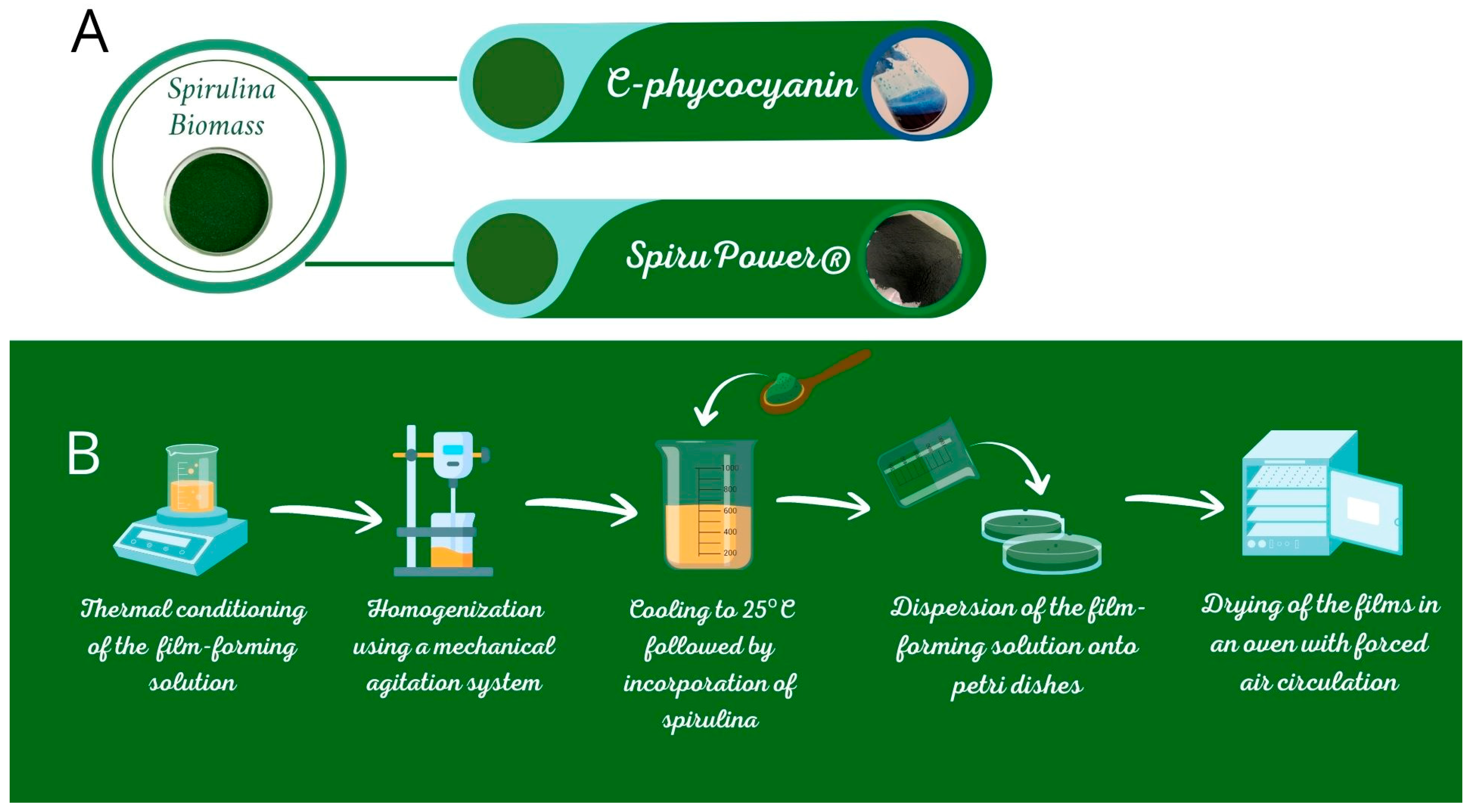

2.2. Characterization of Spirulina Biomass and Biomass Concentrate

2.3. Preparation of Film Formulations

2.3.1. Psyllium Flour Films

2.3.2. Arrowroot Starch Films

2.3.3. Pectin and HPMC Films

2.4. Characterization of HPMC and Pectin Films

2.5. Optical Properties

2.6. Thermogravimetry Analysis (TGA)

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.8. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.9. Determination of Antioxidant Activity by the ABTS, DPPH, and ORAC Methods

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the Proximal Composition of Spirulina Biomass and Biomass Concentrate

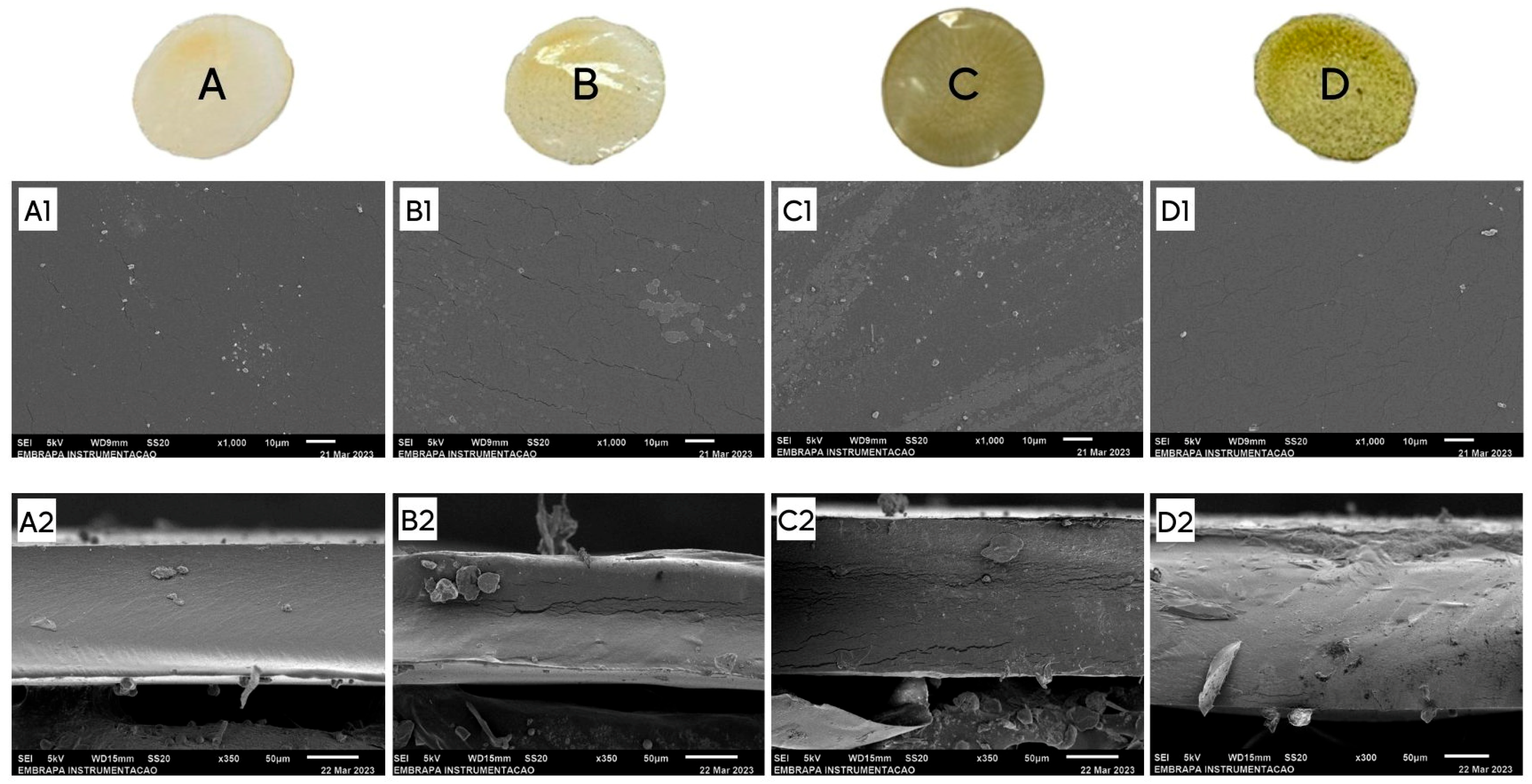

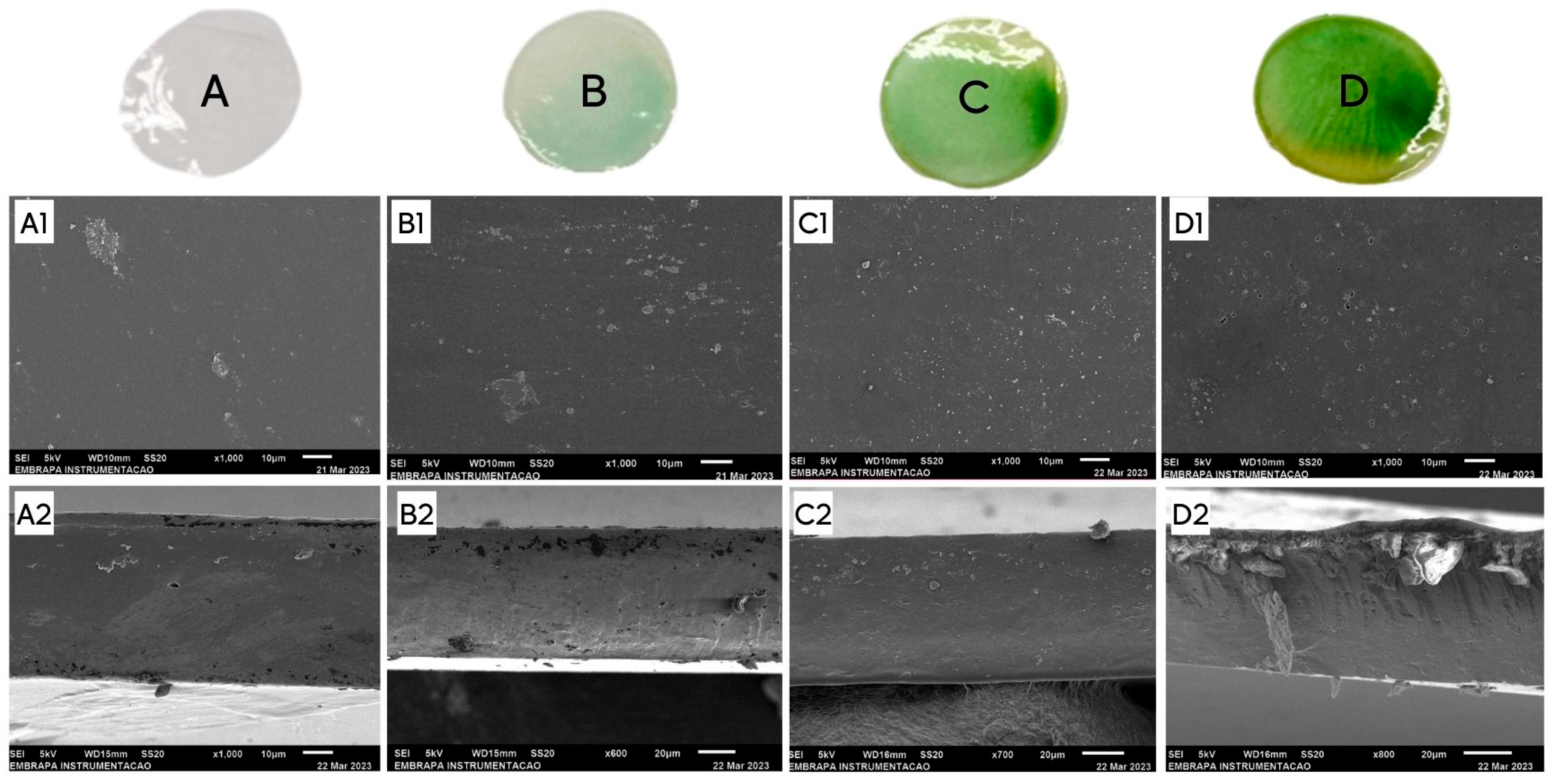

3.2. Films Prepared from Arrowroot Starch and Psyllium Flour

3.3. Films Prepared from HPMC and Pectin

3.3.1. Film Characterization

3.3.2. Moisture Content, Water Solubility, and Water-Vapor Permeability (WVP)

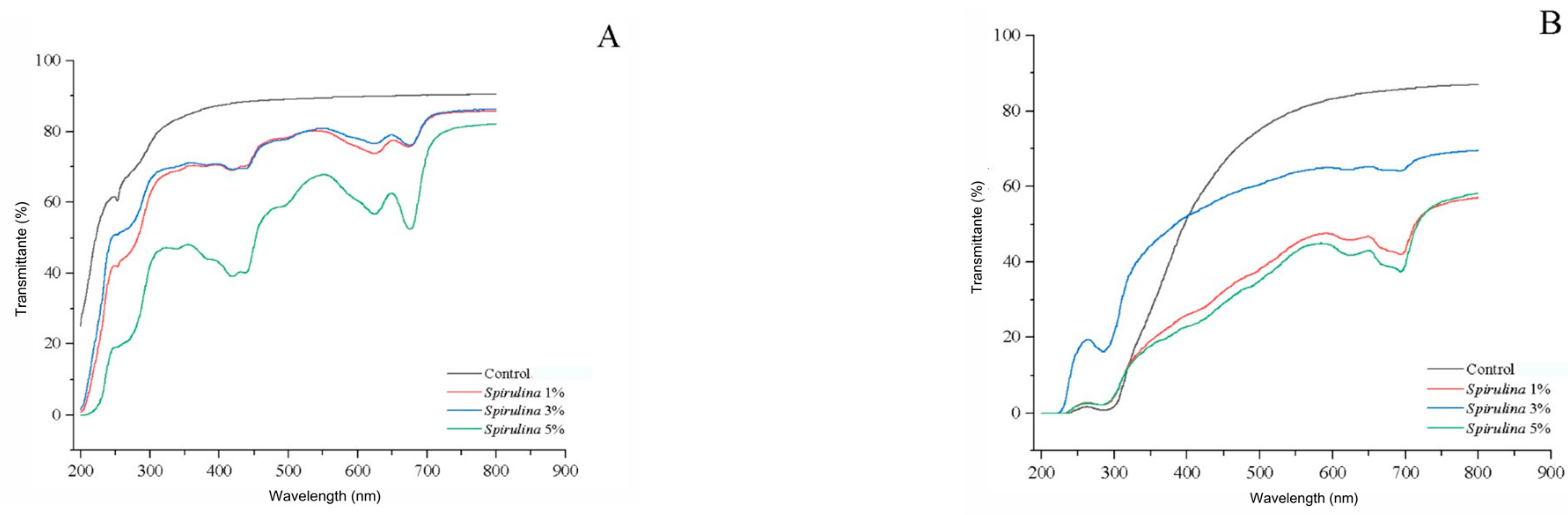

3.4. Optical Properties Results

3.5. Thermogravimetry Analysis (TGA)

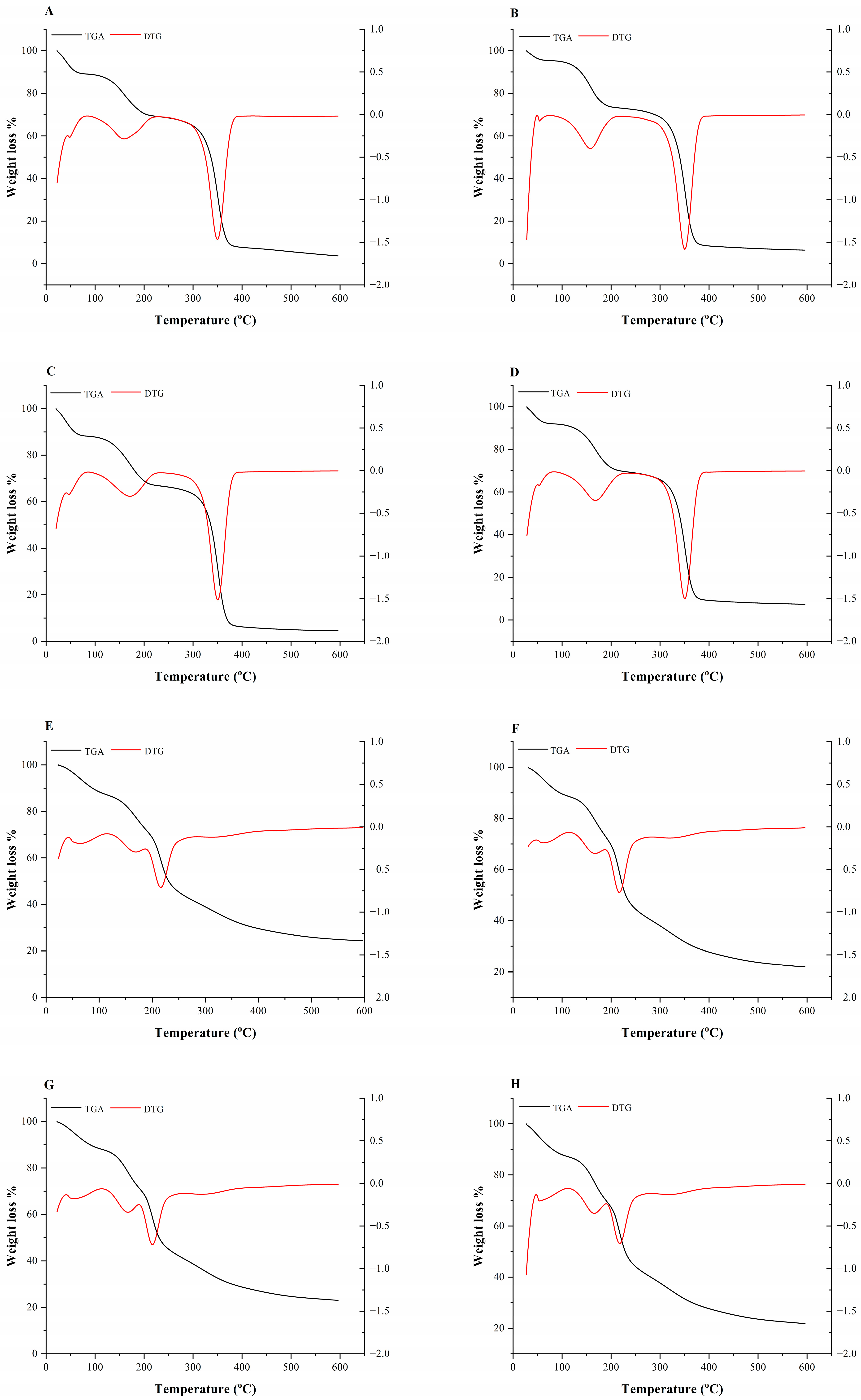

3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

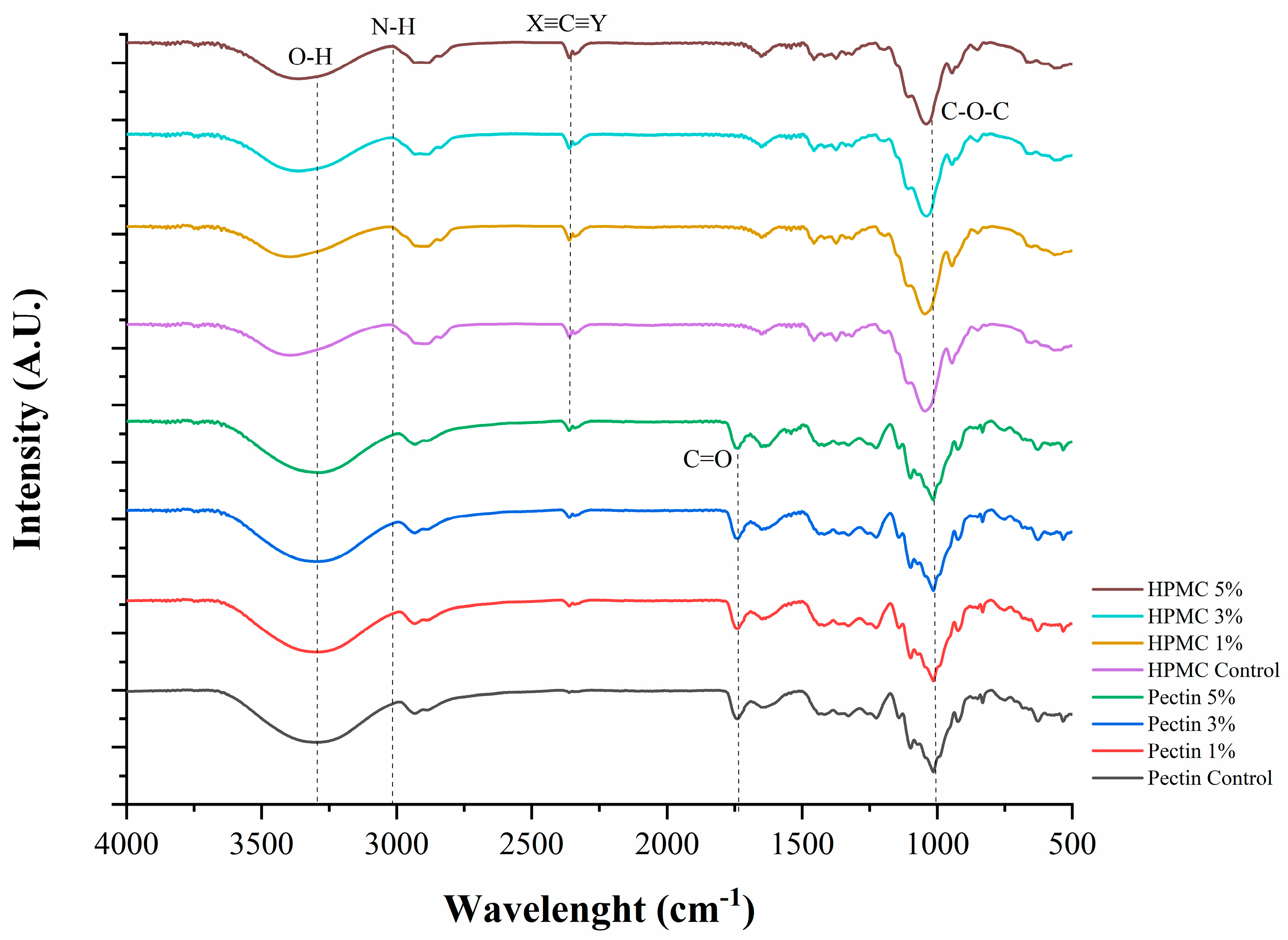

3.7. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

3.8. Determination of Antioxidant Activity by the ABTS, DPPH, and ORAC Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flórez, M.; Guerra-Rodríguez, E.; Cazón, P.; Vázquez, M. Chitosan for Food Packaging: Recent Advances in Active and Intelligent Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, M.; Miller, S.A. Environmental Impacts of Plastic Packaging of Food Products. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, K.Y.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. A Review on Nanomaterials and Nanohybrids Based Bio-Nanocomposites for Food Packaging. Food Chem. 2022, 376, 131912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.; Hu, B.; Feng, J.; Lv, J.; Xie, S. Preparation, and Physicochemical and Biological Evaluation of Chitosan-Arthrospira Platensis Polysaccharide Active Films for Food Packaging. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.; Mehrotra, S.; Priya, S.; Gnansounou, E.; Sharma, S.K. Recent Advances in the Sustainable Design and Applications of Biodegradable Polymers. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 325, 124739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zibaei, R.; Hasanvand, S.; Hashami, Z.; Roshandel, Z.; Rouhi, M.; De Toledo Guimarães, J.; Mortazavian, A.M.; Sarlak, Z.; Mohammadi, R. Applications of Emerging Botanical Hydrocolloids for Edible Films: A Review. Carbohyd. Polym. 2021, 256, 117554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viera, J.S.C.; Marques, M.R.C.; Nazareth, M.C.; Jimenez, P.C.; Castro, Í.B. On Replacing Single-Use Plastic with so-Called Biodegradable Ones: The Case with Straws. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 106, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A.E.; Lensen, S.M.C.; Langeveld, E.; Parker, L.A.; Urbanus, J.H. Plastics in the Global Environment Assessed through Material Flow Analysis, Degradation and Environmental Transportation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875, 162644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Cao, G.; Wang, D.; Ho, S.H. A Sustainable Solution to Plastics Pollution: An Eco-Friendly Bioplastic Film Production from High-Salt Contained Spirulina sp. Residues. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 121773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareth, M.; Marques, M.R.C.; Leite, M.C.A.; Castro, Í.B. Commercial Plastics Claiming Biodegradable Status: Is This Also Accurate for Marine Environments? J Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, S.K.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, V.; Sarsaiya, S.; Anerao, P.; Ghosh, P.; Singh, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Awasthi, M.K. A Comprehensive Review on Recent Advancements in Biodegradation and Sustainable Management of Biopolymers. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 307, 119600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Lalnundiki, V.; Shelare, S.D.; Abhishek, G.J.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, D.; Kumar, A.; Abbas, M. An Investigation of the Environmental Implications of Bioplastics: Recent Advancements on the Development of Environmentally Friendly Bioplastics Solutions. Environ. Res. 2024, 244, 117707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A.; Niamah, A.K. Identification and Antioxidant Activity of Hyaluronic Acid Extracted from Local Isolates of Streptococcus Thermophilus. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 60, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sahlany, S.T.G. Production of Biodegradable Film from Soy Protein and Essential Oil of Lemon Peel and Use It as Cheese Preservative. Basrah J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 30, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramji, V.; Vishnuvarthanan, M. Chitosan Ternary Bio Nanocomposite Films Incorporated with MMT K10 Nanoclay and Spirulina. Silicon 2022, 14, 1209–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrosa, A.P.Q.; Camara, Á.S.; Moura, J.M.; Pinto, L.A.A. Spirulina sp. Biomass Dried/Disrupted by Different Methods and Their Application in Biofilms Production. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 1659–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Wang, H.; Xia, L.; Chen, M.; Li, L.; Cheng, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, S. Colorimetric Film Based on Polyvinyl Alcohol/Okra Mucilage Polysaccharide Incorporated with Rose Anthocyanins for Shrimp Freshness Monitoring. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, A.; Halász, K. Characterization of Edible Biocomposite Films Directly Prepared from Psyllium Seed Husk and Husk Flour. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 20, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Fang, Z. Development and Characterization of Active and PH-Sensitive Films Based on Psyllium Seed Gum Incorporated with Free and Microencapsulated Mulberry Pomace Extracts. Food Chem. 2021, 352, 129333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, F.; Sadeghi, E.; Mohammadi, R.; Rouhi, M.; Taghizadeh, M.; Hosein Shirgardoun, M.; Kariminejad, M. The Physicochemical and Structural Properties of Psyllium Gum/Modified Starch Composite Edible Film. J Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoni, C.G.; De Moura, M.R.; Aouada, F.A.; Camilloto, G.P.; Cruz, R.S.; Lorevice, M.V.; De F.F. Soares, N.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Antimicrobial and Physical-Mechanical Properties of Pectin/Papaya Puree/Cinnamaldehyde Nanoemulsion Edible Composite Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 41, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, H. Characterization and Functional Properties of a Pectin/Tara Gum Based Edible Film with Ellagitannins from the Unripe Fruits of Rubus Chingii Hu. Food Chem. 2020, 325, 126964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Chen, J.; Tan, K.B.; Chen, M.; Zhu, Y. Development of Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose Film with Xanthan Gum and Its Application as an Excellent Food Packaging Bio-Material in Enhancing the Shelf Life of Banana. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarés, L.; Pérez-Masiá, R.; Chiralt, A. The Role of Some Antioxidants in the HPMC Film Properties and Lipid Protection in Coated Toasted Almonds. J. Food Eng. 2011, 104, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, G.F.; Fakhouri, F.M.; De Oliveira, R.A. Extraction and Characterization of Arrowroot (Maranta arundinaceae L.) Starch and Its Application in Edible Films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 186, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Guilherme, D.; Branco, F.P.; Madeira, N.R.; Brito, V.H.; De Oliveira, C.E.; Jadoski, C.J.; Cereda, M.P. Chapter 5-Starch Valorization from Corm, Tuber, Rhizome, and Root Crops: The Arrowroot (Maranta arundinacea L.) Case. In Starches for Food Application; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 167–222. ISBN 978012809440. [Google Scholar]

- Chavoshi, F.; Didar, Z.; Vazifedoost, M.; Shahidi Noghabi, M.; Zendehdel, A. P Syllium Seed Gum Films Loading Oliveria Decumbens Essential Oil Encapsulated in Nanoliposomes: Preparation and Characterization. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 4318–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa Monção, É.; Brandão Grisi, C.V.; De Moura Fernandes, J.; Santos Souza, P.; De Souza, A.L. Active Packaging for Lipid Foods and Development Challenges for Marketing. Food Biosci. 2022, 45, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, A.; Bertuzzi, A.M.S. Preparation, Properties, and Characterization of Coatings and Films. In Edible Films and Coatings: Fundamentals and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.K. Edible Films and Coatings for Fruits and Vegetables. In Encyclopedia of Renewable and Sustainable Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Joya, J.A.; De Leon-Zapata, M.A.; Alvarez-Perez, O.B.; Torres-León, C.; Nieto-Oropeza, D.; Ventura-Sobrevilla, J.; Aguilar, M.A.; Ruelas-Chacón, X.; Rojas, R.; Ramos-Aguiñaga, M.E.; et al. Chapter 1—Basic and Applied Concepts of Edible Packaging for Foods. In Food Packaging and Preservation; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9780128115169. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, A.; Sharma, L.; Maity, T. Enrichment of Edible Coatings and Films with Plant Extracts or Essential Oils for the Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables. In Biopolymer-Based Formulations: Biomedical and Food Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 859–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Rempel, C.; Mclaren, D. Edible Coating and Film Materials: Carbohydrates. In Innovations in Food Packaging, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrona, M.; Cran, M.J.; Nerín, C.; Bigger, S.W. Development and Characterisation of HPMC Films Containing PLA Nanoparticles Loaded with Green Tea Extract for Food Packaging Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 156, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi-Firoozjah, R.; Chabook, N.; Rostami, O.; Heydari, M.; Kolahdouz-Nasiri, A.; Javanmardi, F.; Abdolmaleki, K.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. PVA/Starch Films: An Updated Review of Their Preparation, Characterization, and Diverse Applications in the Food Industry. Polym. Test. 2023, 118, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.B.; Lim, L.T.; Da Rosa Zavareze, E.; Dias, A.R.G.; Costa, J.A.V.; De Morais, M.G. Microalgae Protein Heating in Acid/Basic Solution for Nanofibers Production by Free Surface Electrospinning. J. Food Eng. 2018, 230, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.M.R.; Falcão, J.S.; Tavares, P.P.L.G.; Silva Cruz, L.F.; Nunes, I.L.; Costa, J.A.V.; Druzian, J.I.; Souza, C.O. Utilização de Biomassa de Spirulina platensis Para Desenvolvimento de Molho Com Alto Teor Proteico: Um Estudo Piloto. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 21172–21185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turzillo, A.M.; Campion, C.E.; Clay, C.M.; Nett, T.M. Teores de β-Caroteno Em Suplementos e Biomassa de Spirulina. Ciência Tecnol. Aliment. 2011, 35, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntzler, S.G.; Costa, J.A.V.; Brizio, A.P.D.R.; De Morais, M.G. Development of a Colorimetric PH Indicator Using Nanofibers Containing Spirulina sp. LEB 18. Food Chem. 2020, 328, 126768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T.; Fernández-Sevilla, J.M.; González-López, C.; Acién-Fernández, F.G. Spirulina for the Food and Functional Food Industries. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. 21 CFR Part 73 Listing of Color Additives Exempt from Certification: Spirulina Extract. 2017. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/07/03/2017-13867/listing-of-color-additives-exempt-from-certification-spirulina-extract (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Moghaddas Kia, E.; Ghasempour, Z.; Alizadeh, M. Fabrication of an Eco-Friendly Antioxidant Biocomposite: Zedo Gum/Sodium Caseinate Film by Incorporating Microalgae (Spirulina platensis). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Guerra, I.; Costa, M.; Silva, J.; Gouveia, L. Future Perspectives of Microalgae in the Food Industry. In Cultured Microalgae for the Food Industry Current and Potential Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; ISBN 9780128210802. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, J.B.; Terra, A.L.M.; Costa, J.A.V.; De Morais, M.G. Development of PH Indicator from PLA/PEO Ultrafine Fibers Containing Pigment of Microalgae Origin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stejskal, N.; Miranda, J.M.; Martucci, J.F.; Ruseckaite, R.A.; Aubourg, S.P.; Barros-Velázquez, J. The Effect of Gelatine Packaging Film Containing a Spirulina platensis Protein Concentrate on Atlantic Mackerel Shelf Life. Molecules 2020, 25, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC INTERNATIONAL, 18th ed.; AOAC: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosso, V.V.; Mercadante, A.Z. HPLC–PDA–MS/MS of Anthocyanins and Carotenoids from Dovyalis and Tamarillo Fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 9135–9141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratelli, C.; Bürck, M.; Silva-Neto, A.F.; Oyama, L.M.; De Rosso, V.V.; Braga, A.R.C. Green Extraction Process of Food Grade C-Phycocyanin: Biological Effects and Metabolic Study in Mice. Processes 2022, 10, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.R.C.; Nunes, M.C.; Raymundo, A. The Experimental Development of Emulsions Enriched and Stabilized by Recovering Matter from Spirulina Biomass: Valorization of Residue into a Sustainable Protein Source. Molecules 2023, 28, 6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, S.F.F.; Dos Passos Ramos, S.; Bürck, M.; Braga, A.R.C. Development of Eco-Friendly Solid Shampoo Containing Natural Pigments: Physical-Chemical, Microbiological Characterization and Analysis of Antioxidant Activity. Ind. Biotechnol. 2023, 19, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratelli, C.; Nunes, M.C.; De Rosso, V.V.; Raymundo, A.; Braga, A.R.C. Spirulina and Its Residual Biomass as Alternative Sustainable Ingredients: Impact on the Rheological and Nutritional Features of Wheat Bread Manufacture. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 1258219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürck, M.; Fratelli, C.; Assis, M.; Braga, A.R.C. Naturally Colored Ice Creams Enriched with C-Phycocyanin and Spirulina Residual Biomass: Development of a Fermented, Antioxidant, Tasty and Stable Food Product. Fermentation 2024, 10, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, A.R.C.; Oliveira Filho, J.G.; Lemes, A.C.; Egea, M.B. Nanostructure-Based Edible Coatings as a Function of Food Preservation. In Nanotechnology-Enhanced Food Packaging; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira Filho, J.G.; Lemes, A.C.; Braga, A.R.C.; Egea, M.B. Biodegradable Eco-Friendly Packaging and Coatings Incorporated of Natural Active Compounds. In Food Packaging: Advanced Materials, Technologies, and Innovations; Rangappa, S.M., Jyotishkumar, P., Thiagamani, S.M.K., Siengchin, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 171–205. ISBN 9780429322129. [Google Scholar]

- Kavoosi, G.; Rahmatollahi, A.; Mohammad Mahdi Dadfar, S.; Mohammadi Purfard, A. Effects of Essential Oil on the Water Binding Capacity, Physico-Mechanical Properties, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Gelatin Films. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 57, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E96; Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://store.astm.org/e0096-00.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Egea, M.B.; Fernandes, S.S.; Braga, A.R.C.; Lemes, A.C.; De Oliveira Filho, J.G. Bioactive Phytochemicals from Red Cabbage (Brassica Oleracea) By-Products. In Bioactive Phytochemicals in By-Products from Leaf, Stem, Root and Tuber Vegetables; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chentir, I.; Kchaou, H.; Hamdi, M.; Jridi, M.; Li, S.; Doumandji, A.; Nasri, M. Biofunctional Gelatin-Based Films Incorporated with Food Grade Phycocyanin Extracted from the Saharian Cyanobacterium Arthrospira sp. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 89, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Passos Ramos, S.; Da Trindade, L.G.; Mazzo, T.M.; Longo, E.; Bonsanto, F.P.; De Rosso, V.V.; Braga, A.R.C. Electrospinning Composites as Carriers of Natural Pigment: Screening of Polymeric Blends. Processes 2022, 10, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, H. FTIR Spectroscopic Investigation of Effects of Temperature and Concentration on PEO−PPO−PEO Block Copolymer Properties in Aqueous Solutions. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 6426–6431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliyan, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, R.P.; Chang, C.-M. Determination of Antioxidants by DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity and Quantitative Phytochemical Analysis of Ficus Religiosa. Molecules 2022, 27, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, A.R.C.; De Souza Mesquita, L.M.; Martins, P.L.G.; Habu, S.; De Rosso, V.V. Lactobacillus Fermentation of Jussara Pulp Leads to the Enzymatic Conversion of Anthocyanins Increasing Antioxidant Activity. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 69, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E.; Mariutti, L.R.B.; Faria, A.F.; Mercadante, A.Z. Microcapsules Containing Antioxidant Molecules as Scavengers of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Samborska, K.; Lee, C.C.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E.; Tarhan, Ö.; Taze, B.; Jafari, S.M. Phycocyanin, a Super Functional Ingredient from Algae; Properties, Purification Characterization, and Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 2320–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiari, Z.; Hassani, B.; Sani, I.K.; Talebi, A.; Mohammadi, F.; Zomorodi, S.; Kaveh, M.; Assadpour, E.; Khodaei, S.M.; Eghbaljoo, H.; et al. Characterization of Edible Films Made with Plant Carbohydrates for Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 11, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Filho, J.G. Plant-Based Nanoemulsions with Essential Oils as Edible Coatings: A Novel Approach for Strawberry Preservation. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Araraquara, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, D.L.; Lampman, G.; Kriz, G.; Vyvyan, J. Espectroscopia no infravermelho. In Introdução à Espectroscopia; Cengage Learning: Sao Paolo, Brazil, 2015; pp. 15–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi, F.; Samarasinghe, A. How to Assess Antioxidant Activity? Advances, Limitations, and Applications of in Vitro, in Vivo, and Ex Vivo Approaches. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2025, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahim, A.; Çakir, C.; Ozturk, M.; Şahin, B.; Soulaimani, A.; Sibaoueih, M.; Nasser, B.; Eddoha, R.; Essamadi, A.; El Amiri, B. Chemical Characterization and Nutritional Value of Spirulina platensis Cultivated in Natural Conditions of Chichaoua Region (Morocco). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 141, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, K.; Wal, A.; Sharma, P.; Parveen, A.; Singh, P.; Mishra, P.; Wal, P.; Pramathesh Mishra, N.T. Exploring the Nutritional and Medicinal Potential of Spirulina. Nat. Resour. Hum. Health 2024, 4, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athiyappan, K.D.; Routray, W.; Paramasivan, B. Phycocyanin from Spirulina: A Comprehensive Review on Cultivation, Extraction, Purification, and Its Application in Food and Allied Industries. Food Humanit. 2024, 2, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, A.; Blanco, G. Proteins. In Medical Biochemistry; Academis Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 21–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balti, R.; Ben Mansour, M.; Sayari, N.; Yacoubi, L.; Rabaoui, L.; Brodu, N.; Massé, A. Development and Characterization of Bioactive Edible Films from Spider Crab (Maja Crispata) Chitosan Incorporated with Spirulina Extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1464–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, L.; Yin, K. Heavy Metal Remediation by Nano Zero-Valent Iron in the Presence of Microplastics in Groundwater: Inhibition and Induced Promotion on Aging Effects. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu, R.C.; Nisar, F.; Rodriguez, C.; Durrant, A.; Olabi, A.G. Sustainable Dewatering of Microalgae by Centrifugation Using Image 4-Focus and Matlab Edge Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Energy and Environmental Protection, Graz, Austria, 3–5 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, D.; Baraniak, B. Effect of Candelilla Wax on Functional Properties of Biopolymer Emulsion Films–A Comparative Study. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 41, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, M.M.; Assis, M.; De Oliveira Filho, J.G.; Braga, A.R.C. Spirulina Application in Food Packaging: Gaps of Knowledge and Future Trends. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratelli, C.; Burck, M.; Amarante, M.C.A.; Braga, A.R.C. Antioxidant Potential of Nature’s “Something Blue”: Something New in the Marriage of Biological Activity and Extraction Methods Applied to C-Phycocyanin. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 107, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, R.; Eroglu, E.C.; Aksay, S. Determination of Bioactive Properties of Protein and Pigments Obtained from Spirulina platensis. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Spirulina Biomass | SpiruPower® |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 80.0 a ± 0.0 | 82.22 a ± 0.40 |

| Ash (dry weight) | 0.16 b ± 0.0 | 0.57 a ± 0.01 |

| Lipid (dry weight) | 2.8 a ± 0.01 | 2.39 b ± 0.18 |

| Protein (dry weight) | 57.54 b ± 0.03 | 66.58 a ± 0.62 |

| Total phenolic content (EAG/100 g of sample) | 146.474 b ± 0.01 | 358.65 a ± 0.1 |

| ABTS (µM TE/g) | 50.71 b ± 1.01 | 111.52 a ± 1.4 |

| DPPH (µM TE/g) | 32.41 b ± 0.01 | 87.05 a ± 0.02 |

| Films | Malleability | Fragility | Rigidity | Adherence | Homogeneity | Brightness | Color | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | +++ | - | - | - | +++ | + | + |  |

| A2 | +++ | - | - | - | +++ | ++ | + |  |

| A3 | +++ | - | - | - | ++ | ++ | ++ |  |

| A4 | + | - | - | ++ | +++ | + | + |  |

| A5 | + | - | - | +++ | +++ | + | + |  |

| AR1 | +++ | - | + | - | ++ | ++ | + |  |

| AR2 | +++ | - | + | - | + | ++ | + |  |

| AR3 | +++ | - | + | - | + | ++ | ++ |  |

| AR4 | +++ | - | + | - | ++ | ++ | ++ |  |

| AR5 | ++ | - | ++ | - | ++ | ++ | +++ |  |

| AR6 | + | + | ++ | - | ++ | ++ | +++ |  |

| AR7 | + | ++ | +++ | - | ++ | ++ | +++ |  |

| AR8 | + | +++ | +++ | - | ++ | ++ | +++ |  |

| AB1 | +++ | - | + | - | + | ++ | + |  |

| AB2 | +++ | - | + | - | + | + | ++ |  |

| AB3 | +++ | - | + | - | + | + | +++ |  |

| B1 | +++ | - | +++ | - | +++ | ++ | - |  |

| B2 | +++ | - | +++ | - | +++ | ++ | - |  |

| B3 | + | - | - | +++ | +++ | + | - |  |

| B4 | +++ | - | + | - | +++ | ++ | - |  |

| BR1 | NE | +++ | - | NE | + | NE | + |  |

| BR2 | NE | +++ | - | NE | ++ | NE | ++ |  |

| BR3 | NE | - | - | NE | +++ | NE | +++ |  |

| BB1 | NE | +++ | - | NE | + | NE | + |  |

| BB2 | NE | +++ | - | NE | ++ | NE | ++ |  |

| BB3 | NE | - | - | NE | +++ | NE | +++ |  |

| C1 | +++ | - | - | - | +++ | ++ | + |  |

| CR1 | +++ | - | - | - | ++ | ++ | + |  |

| CR2 | +++ | - | - | - | + | ++ | + |  |

| CR3 | +++ | - | - | - | + | ++ | + |  |

| CB1 | +++ | - | - | - | ++ | ++ | + |  |

| CB2 | +++ | - | - | - | ++ | ++ | ++ |  |

| CB3 | +++ | - | - | - | + | ++ | ++ |  |

| CB4 | +++ | - | - | - | + | ++ | +++ |  |

| D1 | +++ | - | - | - | +++ | ++ | - |  |

| DB1 | +++ | - | - | - | +++ | ++ | + |  |

| DB2 | +++ | - | - | - | ++ | ++ | + |  |

| DB3 | +++ | - | - | - | ++ | ++ | ++ |  |

| Films | Thickness (mm) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) | Tonset (°C) | Tmax (°C) | R600 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPMC | Control | 0.08 b ± 0.01 | 4.26 a ± 0.39 | 16.50 a ± 3.85 | 300.12 | 349.77 | 3.68 |

| Spirulina 1% | 0.07 b ± 0.0 | 4.62 a ± 0.19 | 15.61 a ± 4.40 | 297.94 | 350.85 | 6.36 | |

| Spirulina 3% | 0.08 b ± 0.01 | 3.56 a ± 0.32 | 10.05 b ± 1.58 | 302.59 | 348.9 | 4.47 | |

| Spirulina 5% | 0.08 b ± 0.0 | 3.94 a ± 0.14 | 13.52 ab ± 2.30 | 303.66 | 349.38 | 7.37 | |

| Pectin | Control | 0.11 ab ± 0.04 | 1.48 b ± 0.95 | 3.60 c ± 1.61 | 195.40 | 214.58 | 24.45 |

| Spirulina 1% | 0.13 ab ± 0.01 | 1.22 b ± 1.03 | 2.75 c ± 0.49 | 198.02 | 217.44 | 22.09 | |

| Spirulina 3% | 0.13 ab ± 0.04 | 1.53 b ± 0.33 | 3.24 c ± 0.82 | 198.55 | 214.97 | 23.07 | |

| Spirulina 5% | 0.15 a ± 0.01 | 1.53 b ± 0.48 | 3.82 c ± 0.59 | 199.73 | 219.22 | 21.89 | |

| Films | Moisture Content (%) | Water Solubility (%) | WVP (10−4 g H2O/m·h·Pa−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPMC | Control | 26.4 a ± 1.05 | 100.0 a ± 0.0 | 9.8 d ± 0.1 |

| Spirulina 1% | 23.69 a ± 2.03 | 97.0 a ± 1.0 | 7.3 e ± 1.0 | |

| Spirulina 3% | 22.97 a ± 0.76 | 85.66 b ± 1.52 | 9.7 d ± 0.4 | |

| Spirulina 5% | 18.51 a ± 0.39 | 67.33 c ± 5.68 | 8.9 de ± 1.2 | |

| Pectin | Control | 20.61 a ± 0.88 | 100.0 a ± 0.0 | 13.2 c ± 0.3 |

| Spirulina 1% | 16.09 a ± 5.23 | 97.66 a ± 2.08 | 14.9 bc ± 0.3 | |

| Spirulina 3% | 17.55 a ± 1.54 | 87.66 b ± 6.8 | 16.7 ab ± 0.1 | |

| Spirulina 5% | 16.93 a ± 1.84 | 68.0 c ± 2.64 | 17.4 a ± 0.9 | |

| Films | L* | a* | b* | C* | hº | ΔE | Opacity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPMC | Control | 90.38 a ± 0.25 | −1.12 a ± 0.05 | −0.56 h ± 0.05 | 1.26 h ± 0.05 | 206.13 a ± 6.29 | 8.01 h ± 0.14 | 0.56 d ± 0.0 |

| Spirulina 1% | 80.87 c ± 0.01 | −6.97 d ± 0.01 | 7.48 g ± 0.03 | 10.22 g ± 0.03 | 132.96 b ± 0.21 | 19.85 g ± 0.02 | 1.6 b ± 0.0 | |

| Spirulina 3% | 72.86 e ± 0.01 | −13.03 e ± 0.02 | 17.05 f ± 0.03 | 21.46 d ± 0.04 | 127.40 c ± 0.05 | 33.62 d ± 0.03 | 1.34 c ± 0.0 | |

| Spirulina 5% | 66.51 g ± 0.01 | −16.08 f ± 0.02 | 26.98 b ± 0.03 | 31.41 b ± 0.02 | 120.79 d ± 0.04 | 45.62 b ± 0.03 | 2.67 a ± 0.0 | |

| Pectin | Control | 82.50 b ± 0.01 | −1.71 b ± 0.03 | 18.41 d ± 0.03 | 18.49 e ± 0.04 | 95.31 e ± 0.05 | 27.67 f ± 0.04 | 0.72 c ± 0.0 |

| Spirulina 1% | 79.41 d ± 0.01 | −1.76 dbc ± 0.03 | 17.73 e ± 0.04 | 17.81 f ± 0.03 | 95.66 e ± 0.05 | 28.01 e ± 0.03 | 1.51 b ± 0.17 | |

| Spirulina 3% | 72.06 f ± 0.01 | −1.79 c ± 0.02 | 26.16 c ± 0.04 | 26.22 c ± 0.04 | 93.92 e ± 0.04 | 38.70 c ± 0.02 | 2.44 a ± 0.0 | |

| Spirulina 5% | 60.55 h ± 0.01 | −1.72 b ± 0.03 | 33.80 a ± 0.17 | 33.84 a ± 0.11 | 92.91 e ± 0.03 | 51.18 a ± 0.04 | 2.32 a ± 0.0 | |

| Samples | µmol de TE/g of Film | Samples | µmol de TE/g of Film | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPMC | Control | 26.5 bA ± 6.0 | Pectin | Control | 0.0 bB ± 0.0 |

| Spirulina 1% | 268.28 aA ± 17.75 | Spirulina 1% | 0.0 bB ± 0.0 | ||

| Spirulina 3% | 284.9 aA ± 19.0 | Spirulina 3% | 16.81 aB ± 2.13 | ||

| Spirulina 5% | 320.08 aA ± 35.74 | Spirulina 5% | 36.92 aB ± 7.63 | ||

| Samples | µmol de TE/g of Film | Samples | µmol de TE/g of Film | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPMC | Control | 10.9 cA ± 2.2 | Pectin | Control | 8.21 cB ± 0.62 |

| Spirulina 1% | 125.0 bA ± 7.44 | Spirulina 1% | 32.73 bB ± 8.14 | ||

| Spirulina 3% | 207.9 aA ± 47.5 | Spirulina 3% | 19.72 aB ± 4.17 | ||

| Spirulina 5% | 147.2 aA ± 25.1 | Spirulina 5% | 73.38 aB ± 2.35 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakamoto, M.M.; Oliveira-Filho, J.G.; Assis, M.; Braga, A.R.C. Spirulina-Incorporated Biopolymer Films for Antioxidant Food Packaging. Processes 2025, 13, 4037. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124037

Nakamoto MM, Oliveira-Filho JG, Assis M, Braga ARC. Spirulina-Incorporated Biopolymer Films for Antioxidant Food Packaging. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4037. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124037

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakamoto, Monica Masako, Josemar Gonçalves Oliveira-Filho, Marcelo Assis, and Anna Rafaela Cavalcante Braga. 2025. "Spirulina-Incorporated Biopolymer Films for Antioxidant Food Packaging" Processes 13, no. 12: 4037. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124037

APA StyleNakamoto, M. M., Oliveira-Filho, J. G., Assis, M., & Braga, A. R. C. (2025). Spirulina-Incorporated Biopolymer Films for Antioxidant Food Packaging. Processes, 13(12), 4037. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124037