Comparative Study on the Passivation Effect of Potato Peel and Pig Manure-Based Biochar Prepared by Cyclic Catalytic Pyrolysis on Cd and Pb in Soil: An Experimental Study in a Ring Pipe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomass Raw Materials

2.2. Preparation of Biochar

2.3. Soil Samples

2.4. Experimental Steps

2.4.1. Feasibility Study

2.4.2. Experimental Research on Soil Remediation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Results

3.1.1. Feasibility Experiment

3.1.2. Soil Experiment

3.2. Mechanism Analysis

3.2.1. Basic Physicochemical Properties of PPB-2 and PMB-2

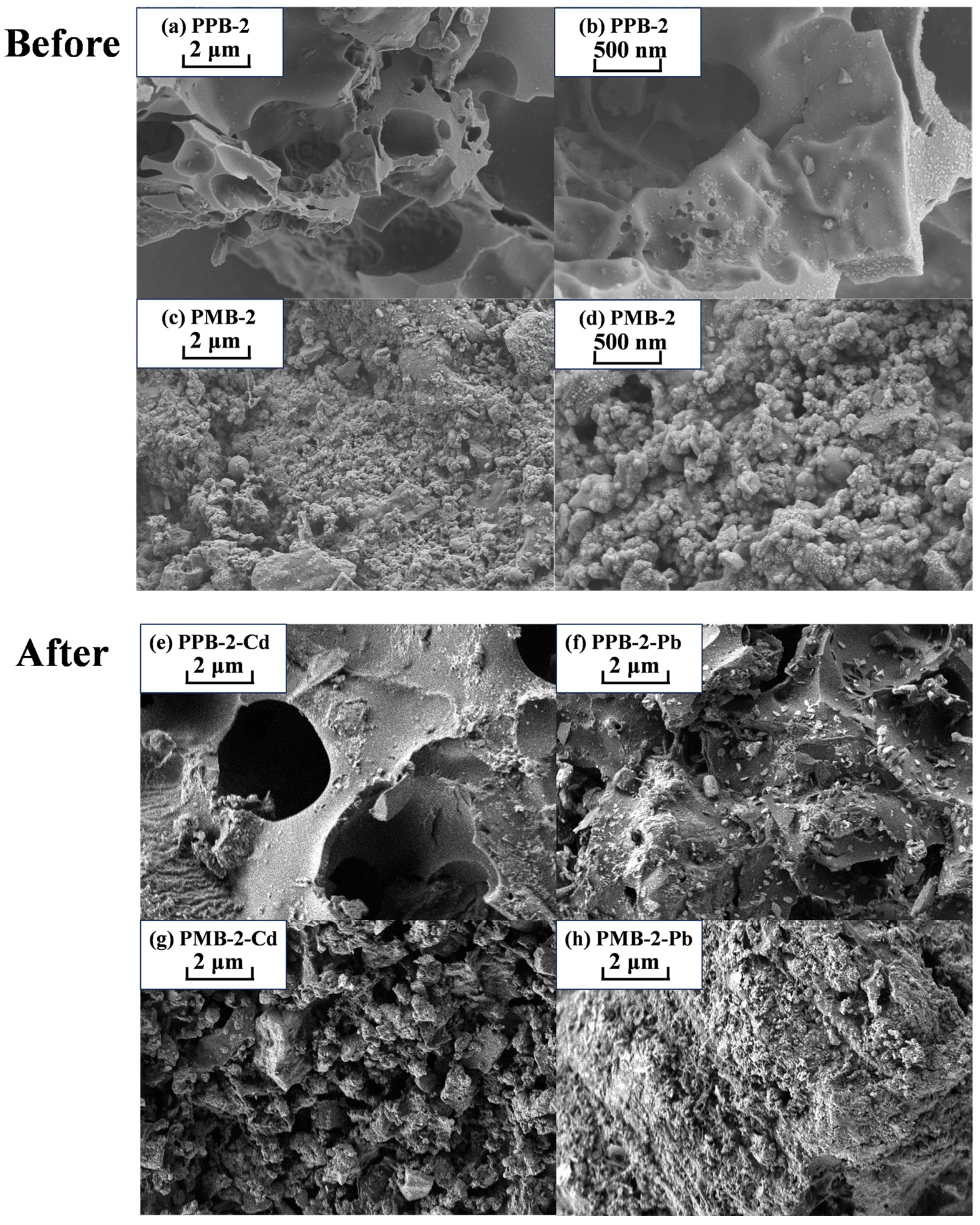

3.2.2. Surface Structure Analysis

3.2.3. Infrared Spectrum Analysis

3.2.4. Phase Composition Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, B.; Yun, Z.; Shi, J.; Jiang, G. Research progress of heavy metal pollution in China: Sources, analytical methods, status, and toxicity. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manta, D.S.; Angelone, M.; Bellanca, A.; Neri, R.; Sprovieri, M. Heavy metals in urban soils: A case study from the city of Palermo (Sicily), Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2002, 300, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Zheng, Y.; He, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, X. Analysis of the Report on the national general survey of soil contamination. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2017, 36, 1689–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarup, L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Song, Q.; Tang, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, F.; Brookes, P.C. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in soil-vegetable system: A multi-medium analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 463, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Lauria, G.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A. The Effects of Cadmium Toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Khan, E.; Ilahi, I. Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology of Hazardous Heavy Metals: Environmental Persistence, Toxicity, and Bioaccumulation. J. Chem. 2019, 2019, 6730305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Liu, X. Influence of Freeze–Thaw Cycles and Binder Dosage on the Engineering Properties of Compound Solidified/Stabilized Lead-Contaminated Soils. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Mao, X.; Shao, X.; Han, F.; Chang, T.; Qin, H.; Li, M. Enhanced Techniques of Soil Washing for the Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils. Agric. Res. 2018, 7, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abkenar, S.D.; Khakipour, N.; Alahdadi, I. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Treatment Technology for the Remediation of Contaminated Soil. Anal. Bioanal. Electrochem. 2024, 16, 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wei, Z.-B.; Wu, Q.-T. [Effectiveness and Mechanisms of Chemical Leaching Combined with Electrokinetic Technology on the Remediation of Heavy Metal Contaminated Soil]. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2023, 44, 1668–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnaji, N.D.; Onyeaka, H.; Miri, T.; Ugwa, C. Bioaccumulation for heavy metal removal: A review. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T. Phytoextraction of heavy metals—The process and scope for remediation of contaminated soils. Soil Environ. 2010, 29, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Fang, L.; Dapaah, M.F.; Niu, Q.; Cheng, L. Bio-Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soil by Microbial-Induced Carbonate Precipitation (MICP)—A Critical Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Ni, Y. Review of Remediation Technologies for Cadmium in soil. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2021; p. 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Deng, Z.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Jiang, P. Mn Pretreatment Improves the Physiological Resistance and Root Exudation of Celosia argentea Linn. to Cadmium Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, T.; Du, H.; Guo, P.; Wang, S.; Ma, M. Research progress in the joint remediation of plants–microbes–soil for heavy metal-contaminated soil in mining areas: A review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S. Preparation, modification and environmental application of biochar: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 1002–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukari, A.; Kaba, J.S.; Dawoe, E.; Abunyewa, A.A. A comprehensive review of the effects of biochar on soil physicochemical properties and crop productivity. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2022, 4, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Wang, Q. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xing, B.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. A high-performance biochar produced from bamboo pyrolysis with in-situ nitrogen doping and activation for adsorption of phenol and methylene blue. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 2872–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkoh, J.N.; Ajibade, F.O.; Atakpa, E.O.; Abdulaha-Al Baquy, M.; Mia, S.; Odii, E.C.; Xu, R. Reduction of heavy metal uptake from polluted soils and associated health risks through biochar amendment: A critical synthesis. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 6, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dad, K.; Nawaz, M.; Dawood, M.; Hassan, R.; Nawaz, H.; Javed, K.; Zou, G.; Zhao, F. A review on biochar, its physicochemical properties and capacity to reduce the toxicity of heavy metals in soil. Biosci. Res. 2022, 19, 118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Gu, Y.; Yang, Z. Application of biochar for the removal of pollutants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 2015, 125, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, B.; Tao, X.; Wang, H.; Li, W.; Ding, X.; Chu, H. Biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal: A review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 155, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Lim, J.E.; Zhang, M.; Bolan, N.; Mohan, D.; Vithanage, M.; Lee, S.S.; Ok, Y.S. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: A review. Chemosphere 2014, 99, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.H.; Gao, M.; Qiu, W.; Islam, S.; Song, Z. Mechanisms for cadmium adsorption by magnetic biochar composites in an aqueous solution. Chemosphere 2020, 246, 125701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, J.; Yue, F.; Yan, X.; Wang, F.; Bloszies, S.; Wang, Y. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation and biochar amendment on maize growth, cadmium uptake and soil cadmium speciation in Cd-contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2018, 194, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Lu, L.; He, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, Y. Applications of Biochar and Modified Biochar in Heavy Metal Contaminated Soil: A Descriptive Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraqqi-A-Kamal, A.; Atkinson, C.J.; Khan, A.; Zhang, K.; Sun, P.; Akther, S.; Zhang, Y. Biochar remediation of soil: Linking biochar production with function in heavy metal contaminated soils. Plant Soil Environ. 2021, 67, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Xia, Y.; Lan, G.; Yan, B.; Yu, Y.; Xiong, X.; Zou, J.; Zhu, Y. Study on the effect of cyclic catalytic pyrolysis on sludge pyrolysis products. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, X.; Shi, W.; Huang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zuo, X. The effect of cyclic catalytic pyrolysis system on the co-pyrolysis products of sewage sludge and chicken manure, focusing on the yield and quality of syngas. Energy 2025, 314, 134182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Chen, H.; Malik, Z.; Xiao, Q.; Lu, S. Comparative study on the potential risk of contaminated-rice straw, its derived biochar and phosphorus modified biochar as an amendment and their implication for environment. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, C.C.; Chagas, J.K.M.; da Silva, J.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Short-term effects of a sewage sludge biochar amendment on total and available heavy metal content of a tropical soil. Geoderma 2019, 344, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Meng, J.; Ok, Y.S.; Wang, C.-H. Enhancing agricultural productivity with biochar: Evaluating feedstock and quality standards. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 29, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-j.; Liu, H.; Zeng, F.-k.; Yang, Y.-c.; Xu, D.; Zhao, Y.-C.; Liu, X.-f.; Kaur, L.; Liu, G.; Singh, J. Potato processing industry in China: Current scenario, future trends and global impact. Potato Res. 2023, 66, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z. EKC Empirical Analysis of Agricultural Non-point Source Pollution Sources in Chongqing City. J. Southwest China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 40, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, T.; Lan, G.; Shen, J.; Yu, Y.; Xue, P.; Chen, D.; Wang, M.; Fu, C. A study of co-pyrolysis of sewage sludge and rice husk for syngas production based on a cyclic catalytic integrated process system. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 118946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 15618-2018; Soil Environmental Quality Risk Control Standard for Soil Contamination of Agricultural Land. China Environmental Publishing Group: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Su, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, M.; Xie, Y.; Shi, R.; Huang, X.; Tuo, Y.; He, X.; Xiang, P. Mn-modified bamboo biochar improves soil quality and immobilizes heavy metals in contaminated soils. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 34, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ni, Q.; Wu, Y.; Fu, C.; Ping, W.; Bai, H.; Li, M.; Huang, H.; Liu, H. Passivation and Remediation of Pb and Cr in Contaminated Soil by Sewage Sludge Biochar Tubule. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 49102–49111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Hu, Y.-w.; Ji, M.-y.; Sang, W.-j.; Li, D.-x. Adsorptive characteristics of rice straw biochar on composite heavy metals Cd2+ and Pb2+ in soil. Res. Environ. Sci. 2020, 33, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, K.; Jiao, Z.; Zhan, W.; Ge, S.; Ning, S.; Fang, S.; Ruan, X. Simultaneous removal of Cu2+, Cd2+ and Pb2+ by modified wheat straw biochar from aqueous solution: Preparation, characterization and adsorption mechanism. Toxics 2022, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burachevskaya, M.; Minkina, T.; Bauer, T.; Lobzenko, I.; Fedorenko, A.; Mazarji, M.; Sushkova, S.; Mandzhieva, S.; Nazarenko, A.; Butova, V.; et al. Fabrication of biochar derived from different types of feedstocks as an efficient adsorbent for soil heavy metal removal. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostani, A.; Meng, X.; Jiao, L.; Rončević, S.D.; Zhang, P.; Sun, H. Differentiated effects and mechanisms of N-, P-, S-, and Fe-modified biochar materials for remediating Cd- and Pb-contaminated calcareous soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chintala, R.; Mollinedo, J.; Schumacher, T.E.; Malo, D.D.; Julson, J.L. Effect of biochar on chemical properties of acidic soil. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2014, 60, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, J.; Meng, Y.; Aihemaiti, A.; Xu, Y.; Xiang, H.; Gao, Y.; Chen, X. Preparation, Environmental Application and Prospect of Biochar-Supported Metal Nanoparticles: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 122026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Strezov, V.; Chan, K.Y.; Ziolkowski, A.; Nelson, P.F. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on production and nutrient properties of wastewater sludge biochar. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhong, J.; Wu, M.; Liu, Q.; Yang, L.; Xu, X.; Wang, W.; Guan, X.; Lu, M. Turning Waste into Treasure: A Magnetic Sludge-Based Biochar for Efficient Co-Removal of Tetracycline and Cu2+. Langmuir 2025, 41, 32994–33008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, H.; Luo, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, S. Evolution of the chemical composition, functional group, pore structure and crystallographic structure of bio-char from palm kernel shell pyrolysis under different temperatures. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 127, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| pH | Pb (mg/kg) | Cd (mg/kg) | Maximum Field Capacity | Bulk Density (N/m3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treated soil samples | 7.93 | 718.28 | 22.36 | 19.96% | 1.67 |

| Biochar | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Ring Pipe (W/W) | |

| CK | 0 |

| PPB-2 | 0.74% |

| PMB-2 | 1.24% |

| Biochar Type | Pyrolysis Method | Heavy Metals | Removal Efficiency (%) | Application Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sludge biochar | Conventional | Cd, Pb | 38.4 (Cd), 23.3 (Pb) | Direct mixing | [41] |

| Rice straw | Conventional | Pb, Cr | 97.58 (Pb), 68.35 (Cr) | yellow sand simulated soil column filtration | [42] |

| Wheat straw | Modified | Cd, Pb, Cu | 22.83 (Cd), 49.38 (Pb), 18.36 (Cu) | Direct mixing | [43] |

| PPB-2 | CCPS | Cd, Pb | 49.87 (Cd), 44.74 (Pb) | Ring pipe | This study |

| PMB-2 | CCPS | Cd, Pb | 51.21 (Cd), 44.3 (Pb) | Ring pipe | This study |

| Biochar | Yield (%) | Ash Content (%) | Volatile Matter (%) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPB-2 | 25.45 | 8.46 | 87.03 | 9.67 |

| PMB-2 | 38.17 | 21.18 | 74.09 | 11.06 |

| Biochar Type | Specific Surface Area (m2·g−1) | Total Pore Volume (cm3·g−1) | Average Pore Size (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before adsorption | PPB-2 | 15.20 | 0.1200 | 25.0 |

| PMB-2 | 10.15 | 0.0688 | 27.1 | |

| After adsorption | PPB-2-Cd | 2.17 | 0.0281 | 51.7 |

| PPB-2-Pb | 9.50 | 0.0750 | 32.5 | |

| PMB-2-Cd | 7.80 | 0.0520 | 30.8 | |

| PMB-2-Pb | 1.61 | 0.0136 | 33.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Q.; Shi, W.; Tu, R.; Tian, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, C.; Lan, G.; Wu, Y. Comparative Study on the Passivation Effect of Potato Peel and Pig Manure-Based Biochar Prepared by Cyclic Catalytic Pyrolysis on Cd and Pb in Soil: An Experimental Study in a Ring Pipe. Processes 2025, 13, 4029. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124029

Zheng Q, Shi W, Tu R, Tian Y, Wang H, Zhao Y, Shen J, Wang C, Lan G, Wu Y. Comparative Study on the Passivation Effect of Potato Peel and Pig Manure-Based Biochar Prepared by Cyclic Catalytic Pyrolysis on Cd and Pb in Soil: An Experimental Study in a Ring Pipe. Processes. 2025; 13(12):4029. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124029

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Qiushi, Wenjing Shi, Ran Tu, Yuquan Tian, Huanyu Wang, Yue Zhao, Jingyu Shen, Can Wang, Guoxin Lan, and Yan Wu. 2025. "Comparative Study on the Passivation Effect of Potato Peel and Pig Manure-Based Biochar Prepared by Cyclic Catalytic Pyrolysis on Cd and Pb in Soil: An Experimental Study in a Ring Pipe" Processes 13, no. 12: 4029. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124029

APA StyleZheng, Q., Shi, W., Tu, R., Tian, Y., Wang, H., Zhao, Y., Shen, J., Wang, C., Lan, G., & Wu, Y. (2025). Comparative Study on the Passivation Effect of Potato Peel and Pig Manure-Based Biochar Prepared by Cyclic Catalytic Pyrolysis on Cd and Pb in Soil: An Experimental Study in a Ring Pipe. Processes, 13(12), 4029. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13124029