Day-Ahead Economic Dispatch Optimization for Industrial Consumers Utilizing Shared Energy Storage Stations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology and Analysis

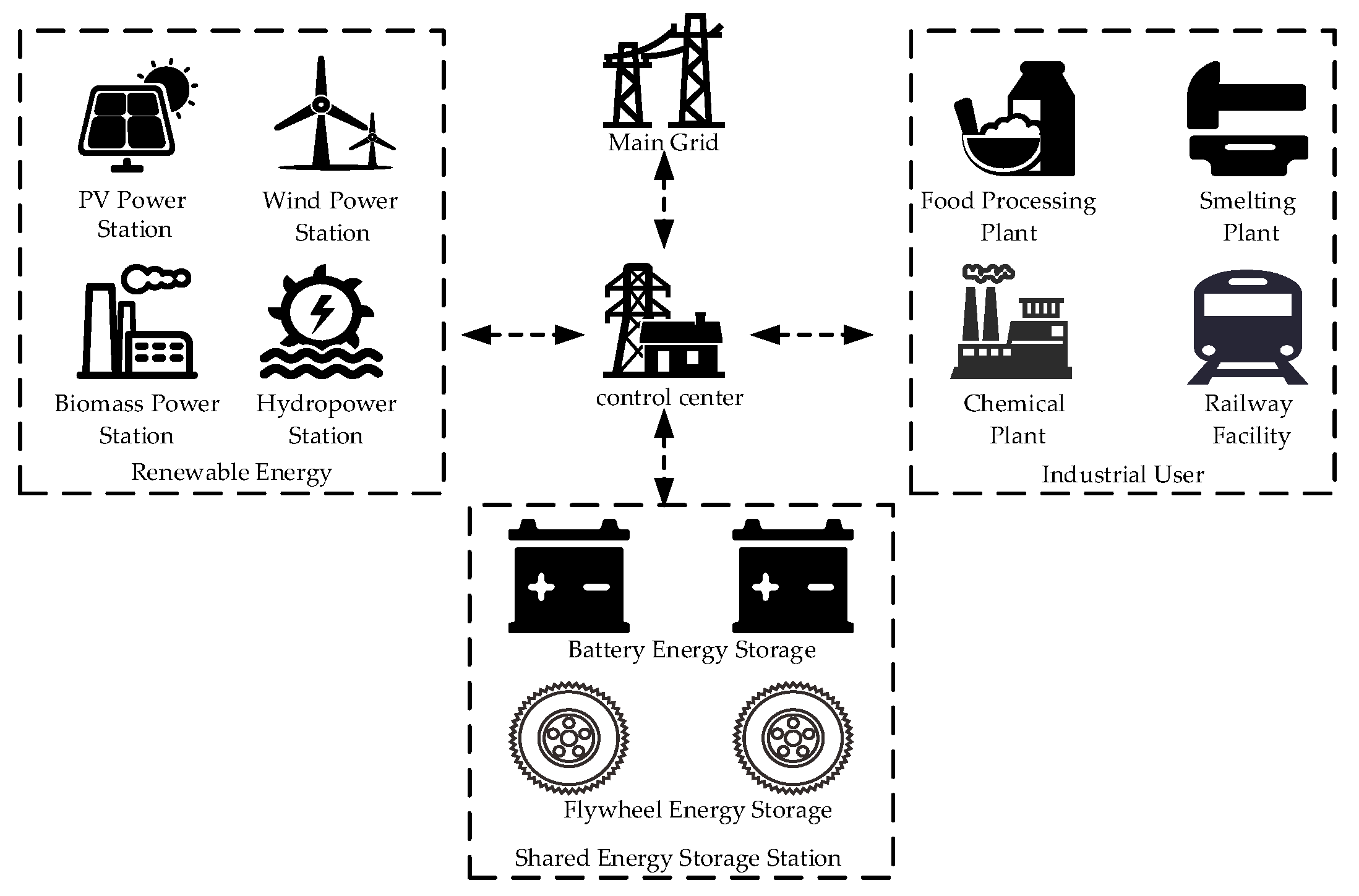

3.1. Shared Energy Storage Station Concept and Operation Mode

3.2. Classification of Industrial User Loads and Energy Storage Configuration Requirements

3.2.1. Load Type A: Dual-Peak Load Curve (Food Processing Plant)

3.2.2. Load Type B: Night-Peak Load Curve (Smelting Plant)

3.2.3. Load Type C: Stable Load Curve (Chemical Plant)

3.2.4. Load Type D: Highly Fluctuating Load Curve (Railway/Transit)

3.3. Renewable Energy Power

3.4. Time-of-Use Electricity Prices and Shared Energy Storage Parameters

3.5. Optimization Scheduling Model Based on Shared Energy Storage

3.5.1. Objective Function

3.5.2. Constraints

3.5.3. Solution Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Optimization Results for System Integration with a Shared Energy Storage Station

4.2. Economic Analysis of User Groups Integrated with a Shared Energy Storage Station

4.2.1. Scenario 1: Users Without Energy Storage

4.2.2. Scenario 2: Independent Energy Storage Configuration Within Each User

4.2.3. Scenario 3: Users Integrated with a Shared Energy Storage Station

4.2.4. Scenario 4: Shared Energy Storage Station Incorporating a Short-Duration High-Power Flywheel Energy Storage Unit

4.2.5. Comparative Analysis from Scenario 1 to Scenario 4

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Meaning | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Total daily operating economic cost of all users connected to the SESS | CNY/day | |

| Cost of purchasing electricity from the distribution grid | CNY | |

| Service fee paid to the SESS operator for using storage capacity | CNY | |

| Depreciation cost resulting from battery lifetime degradation | CNY | |

| Number of users | — | |

| Total number of time intervals in the scheduling horizon | — | |

| Electricity price for purchasing power from the main grid at time interval | CNY/kWh | |

| Service fee rate charged to the user for using the SESS at time interval | CNY/kWh | |

| Duration of a single scheduling interval | min | |

| Electricity purchasing power from the grid by user at time interval | kW | |

| Discharge power supplied by the SESS to user at time interval | kW | |

| Charging/discharging power from the SESS by user at time interval | kW | |

| Unit depreciation cost per charging–discharging cycle | CNY/kWh | |

| Charging power of the SESS at time interval | kW | |

| Discharging power of the SESS at time interval | kW | |

| Renewable energy generation power of user at time interval | kW | |

| Electrical load demand power of user at time interval | kW | |

| Maximum allowable charging and discharging power for a user utilizing the SESS | kW | |

| Discharging state indicator for user at time interval (binary) | — | |

| Charging state indicator for user at time interval (binary) | — | |

| Maximum state of charge (SOC) of the SESS | kWh | |

| Minimum state of charge (SOC) of the SESS | kWh | |

| State of charge (SOC) of the SESS at time interval | kWh | |

| Self-discharge rate of the SESS (generally negligible) | — | |

| Charging efficiency of the SESS | — | |

| Discharging efficiency of the SESS | — | |

| Charging state indicator of the SESS | — | |

| Discharging state indicator of the SESS | — | |

| Maximum charging and discharging power of the SESS | kW | |

| Sufficiently large constant in the Big-M method | — |

References

- Sinsel, S.R.; Riemke, R.L.; Hoffmann, V.H. Challenges and solution technologies for the integration of variable renewable energy sources: A review. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 2271–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Du, E.; Zhang, N.; Kang, C. Impact of high renewable penetration on the power system operation mode: A data-driven approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Nejad, R.R.; Sun, W. Robust distribution system load restoration with time-dependent cold load pickup. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3204–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Tian, J.; Chen, L. Managing energy infrastructure to decarbonize industrial parks in China. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B.; Melatti, I.; Mancini, T.; Prodanovic, M.; Tronci, E. Residential demand management using individualized demand aware price policies. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, B. Towards carbon neutrality by implementing carbon emissions trading scheme: Policy evaluation in China. Energy Policy 2021, 157, 112510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Lin, J.; Song, Y.H.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.H. A hierarchical strategy for restorative self-healing of hydrogen-penetrated distribution systems considering energy sharing via mobile resources. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 99, 1388–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Qiu, J.; Zhao, J.; Chai, Q.; Dong, Z.Y. Bargaining game-based profit allocation of virtual power plant in frequency regulation market considering battery cycle life. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 2913–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yin, B.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S. Evaluating the PV system expansion potential of existing integrated energy parks: A case study in North China. Appl. Energy 2023, 330, 120310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, H.; Huang, J.; Lin, X. Virtual energy storage sharing and capacity allocation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 1112–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Qiu, J.; Tao, Y. Individualized pricing of energy storage sharing based on discount sensitivity. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 4642–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.; Park, J. Demand-side management with shared energy storage system in smart grid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4466–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Esmaeilbeigi, R.; Charkhgard, H. The utilization of shared energy storage in energy systems: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3163–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmohamadi, H.; Keypour, R.; Bak-Jensen, B.; Pillai, J.R.; Khooban, M.H. Robust self-scheduling of operational processes for industrial demand response aggregators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hug, G.; Harjunkoski, I. Cost-effective scheduling of steel plants with flexible EAFs. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Q.Y.; Zhang, C.Q. Research on the optimal operation of a novel renewable multi-energy complementary system in rural areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Naeem, M.; Ejaz, W.; Iqbal, M.; Anpalagan, A. Renewable energy assisted traffic aware cellular base station energy cooperation. Energies 2018, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.X.; Chen, Y. A distributed online algorithm for promoting energy sharing between EV charging stations. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 1158–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Kwon, S. Analysis on impact of shared energy storage in residential community: Individual versus shared energy storage. Appl. Energy 2021, 282, 116172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Baeyens, E.; Poolla, K.; Khargonekar, P.P.; Varaiya, P. Sharing storage in a smart grid: A coalitional game approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 4379–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Mastroianni, C.; Scarcello, L.; Spezzano, G. IoT-based energy sharing model for sizing storage systems in energy communities. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th IEEE International Energy Conference (ENERGYCon), Gammarth, Tunisia, 28 September–1 October 2020; pp. 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Wang, S.W. A hierarchical optimal control strategy for continuous demand response of building HVAC systems to provide frequency regulation service to smart power grids. Energy 2021, 230, 120741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Xu, J.; Liao, S.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ke, D.; Wang, J. A bi-level scheduling model for virtual power plants with aggregated thermostatically controlled loads and renewable energy. Appl. Energy 2018, 224, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. Optimal operation with dynamic partitioning strategy for centralized shared energy storage station with integration of large-scale renewable energy. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 12, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, A.; Yuan, Y.; Feng, C.; Hou, Y.; Wang, A.; Huang, Y. Low-carbon economic scheduling of park integrated energy system considering user-side shared energy storage. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Smart Grid and Smart Cities (ICSGSC), Lanzhou, China, 22–24 September 2023; pp. 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Gao, B. A two-stage stochastic unit commitment considering shared energy storage and renewable energy sources. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Power Energy Systems and Applications (ICoPESA), Nanjing, China, 24–26 February 2023; pp. 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, G.; Spanos, C.J. Optimal sharing and fair cost allocation of community energy storage. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 5052–5063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, B.H.; Bhatti, D.M.S.; Ullah, I. Combinatorial auctions for energy storage sharing amongst the households. J. Energy Storage 2018, 19, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Huang, H.; Song, X.; Pimm, A.J.; Wu, X.; Liao, S. Optimal sizing and operations of shared energy storage systems in distribution networks: A bi-level programming approach. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Sun, Y.; Lovati, M.; Zhang, X. Solar-photovoltaic-power-sharing based design optimization of distributed energy storage systems for performance improvements. Energy 2021, 222, 119931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, X.Z.; Kong, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.W. Optimal participation and cost allocation of shared energy storage considering customer directrix load demand response. J. Energy Storage 2024, 81, 110404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Jiang, J.; Ye, X.; Gao, D.W.; Ai, X. Demand response flexibility potential trading in smart grids: A multileader multifollower Stackelberg game approach. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 2023, 53, 2664–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, H.; Avramidis, I.I.; Capitanescu, F.; Heiselberg, P.K. Local energy communities in service of sustainability and grid flexibility provision: Hierarchical management of shared energy storage. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 1523–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Ye, T.; Yang, Y.; Pan, F.; Feng, L.; Qi, S.; Huang, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Joint Low-Carbon Optimization for User-Side Shared Energy Storage–Distribution Networks. Processes 2024, 12, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Qi, L.; Pan, N.; Hou, M.; Yang, J. Optimization method for load aggregation scheduling in industrial parks considering multiple interests and adjustable load classification. Energy 2025, 326, 135887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turdybek, B.; Tostado-Véliz, M.; Mansouri, S.A.; Jordehi, A.R.; Jurado, F. A local electricity market mechanism for flexibility provision in industrial parks involving Heterogenous flexible loads. Appl. Energy 2024, 359, 122748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Mifta, Z.; Papiya, S.J.; Roy, P.; Dey, P.; Salsabil, N.A.; Chowdhury, N.-U.-R.; Farrok, O. A state-of-the-art comparative review of load forecasting methods: Characteristics, perspectives, and pplications. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, D.; Huang, X.; Lou, B.; Liu, D. Optimal allocation of power supply systems in industrial parks considering multi-energy complementarity and demand response. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrani, A.; Berrada, A. A Comprehensive Review on Techno-economic Assessment of Hybrid Energy Storage Systems Integrated with Renewable Energy. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 111010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutikno, T.; Arsadiando, W.; Wangsupphaphol, A.; Yudhana, A.; Facta, M. A Review of Recent Advances on Hybrid Energy Storage System for Solar Photovoltaics Power Generation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 42346–42364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, A.; Yang, Q. Scenario-based investment planning of isolated multi-energy microgrids considering electricity, heating and cooling demand. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varasteh, F.; Nazar, M.S.; Heidari, A.; Shafie-khah, M.; Catalão, J.P.S. Distributed energy resource and network expansion planning of a CCHP based ctive microgrid considering demand response programs. Energy 2019, 172, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yin, S.; Chen, X.; She, L.; Fu, Z.; Liu, H. Distributed Shared Energy Storage Double-Layer Optimal Configuration for Source-Grid Co-Optimization. Processes 2023, 11, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Barkouki, B.; Laamim, M.; Rochd, A.; Chang, J.-W.; Benazzouz, A.; Ouassaid, M.; Kang, M.; Jeong, H. An Economic Dispatch for a Shared Energy Storage System Using MILP Optimization: A Case Study of a Moroccan Microgrid. Energies 2023, 16, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.H.; Hussain, G.A.; Alsmadi, Y.M.S.; Haider, Z.M.; Mansoor, W.; Lehtonen, M. Integrating Energy Storage Technologies with Renewable Energy Sources: A Pathway Toward Sustainable Power Grids. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Correa, D.; Arévalo, P.; Martinez, S. Pathways to 100% Renewable Energy in Island Systems: A Systematic Review of Challenges, Solutions Strategies, and Success Cases. Technologies 2025, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.S.; Abid, M.I.; Akmal, M.; Munir, H.M.; Haider, Z.M.; Khan, M.O.; Alamri, B.; Alqarni, M. A Comprehensive Assessment of Storage Elements in Hybrid Energy Systems to Optimize Energy Reserves. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Load Profile Type | Load Curve Characteristics | Representative Industrial Users | Implications for Energy Storage Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bi-Peak Load Profile | Two daily demand peaks at midday and early evening; pronounced peak–valley differences | Food processing plants, pharmaceutical factories, electronics manufacturing, large shopping malls | Charge during off-peak hours (night/morning) and discharge at midday and evening peaks; enable peak shaving and valley filling |

| Night-Peak Load Profile | High nighttime load and low daytime load | Smelters, pumping stations, port cargo handling facilities | Charge in low-price daytime periods and discharge at night; alleviate nighttime peak demand pressure |

| Flat Load Profile | Stable demand throughout the day with minimal variations | Chemical plants (fertilizers, plastics, oil refining) | Exploit time-of-use tariff arbitrage; relatively small capacity requirement |

| Highly Fluctuating Load Profile | Multiple sharp peaks and deep troughs with high fluctuation frequency | Metro systems, railway traction loads, port shore-to-ship power systems | Deploy high-power storage systems to smooth frequent load fluctuations and protect grid stability |

| Tariff Category | Time Period (hh:mm) | Grid Purchase Price (CNY/kWh) |

|---|---|---|

| Peak | 8:00–11:00, 17:00–22:00 | 1.1549 |

| Flat | 11:00–17:00, 22:00–24:00 | 0.6716 |

| Valley | 0:00–8:00 | 0.2811 |

| Indicator | User A | User B | User C | User D | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curtailed Energy (kWh) | 840 | 206 | 0 | 44 | 1090 |

| Electricity Purchased from Grid (kWh) | 1896 | 1069 | 1659 | 675.4 | 5300 |

| Total Grid Purchase Cost (CNY) | 1702 | 587 | 1079 | 505 | 3874 |

| Indicator | User A | User B | User C | User D | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity (kWh) | 907 | 195 | 0 | 58 | 1161 |

| Max. Charging/Discharging Power (kW) | 235 | 46 | 0 | 23 | 281 |

| Daily Average Grid Purchase Cost (CNY) | 625 | 352 | 981 | 376 | 2334 |

| Daily Average Investment Cost (CNY) | 1075 | 226 | 0 | 79 | 1380 |

| Total Operating Cost (CNY) | 1670 | 578 | 981 | 455 | 3714 |

| Indicator | User A | User B | User C | User D | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Average Electricity Purchased (kWh) | 938 | 767 | 1023 | 398 | 3126 |

| Daily Average Grid Purchase Cost (CNY) | 728 | 415 | 574 | 259 | 1976 |

| Daily Average Service Fee (CNY) | 947 | 144 | 164 | 113 | 1369 |

| Daily Average Operating Cost (CNY) | 1675 | 559 | 738 | 372 | 3345 |

| Parameter | BESS | FESS |

|---|---|---|

| Unit power cost (CNY/kW) | 1800 | 1000 |

| Unit capacity cost (CNY/kWh) | 1500 | 5000 |

| Rated power (kW) | 327 | 20 |

| Rated capacity (kWh) | 1073.33 | 1.67 |

| Lifetime (years) | 8 | 30 |

| Indicator | User A | User B | User C | User D | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Average Electricity Purchased (kWh) | 938 | 767 | 1023 | 380 | 3108 |

| Daily Average Grid Purchase Cost (CNY) | 728 | 415 | 574 | 247 | 1964 |

| Daily Average Service Fee (CNY) | 947 | 144 | 164 | 113 | 1368 |

| Daily Average Operating Cost (CNY) | 1675 | 559 | 738 | 360 | 3332 |

| Scenarios | User A Daily Operating Cost (CNY) | User B Daily Operating Cost (CNY) | User C Daily Operating Cost (CNY) | User D Daily Operating Cost (CNY) | Total Daily Operating Cost (CNY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 No storage | 1702 | 587 | 1079 | 505 | 3874 |

| S2 Independent storage | 1670 | 578 | 981 | 455 | 3714 |

| S3 Shared storage | 1675 | 559 | 738 | 372 | 3345 |

| S4 Hybrid storage (BESS + FES) | 1675 | 559 | 738 | 360 | 3332 |

| Indicator | S1 No Storage | S2 Independent Storage | S3 Shared Storage | S4 Hybrid Storage (BESS + FES) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total curtailed energy (kWh) | 1090 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total electricity purchased (kWh) | 5300 | ↓21% (relative to S1) | ↓41% (relative to S1) | ↓41.4% (relative to S1) |

| Total operating cost (CNY) | 3874 | ↓4.1% (relative to S1) | ↓13.6% (relative to S1) | ↓14.0% (relative to S1) |

| Total storage capacity (kWh) | — | 1161 | ↓7.4% (relative to S2) | ↓7.4% (relative to S2) |

| Total storage power rating (kW) | — | 281 | ↑23.5% (relative to S2) | ↑23.5% (relative to S2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, C.; Zhang, Q.; Mei, D.; Chen, E.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X. Day-Ahead Economic Dispatch Optimization for Industrial Consumers Utilizing Shared Energy Storage Stations. Processes 2025, 13, 3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123964

Tian C, Zhang Q, Mei D, Chen E, Li Z, Zhang X. Day-Ahead Economic Dispatch Optimization for Industrial Consumers Utilizing Shared Energy Storage Stations. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123964

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Chenghuan, Qinghu Zhang, Dan Mei, Erqiang Chen, Zhengping Li, and Xudong Zhang. 2025. "Day-Ahead Economic Dispatch Optimization for Industrial Consumers Utilizing Shared Energy Storage Stations" Processes 13, no. 12: 3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123964

APA StyleTian, C., Zhang, Q., Mei, D., Chen, E., Li, Z., & Zhang, X. (2025). Day-Ahead Economic Dispatch Optimization for Industrial Consumers Utilizing Shared Energy Storage Stations. Processes, 13(12), 3964. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123964