Experimental Investigation on Fracture Behaviors of Straight-Wall Tunnels with Defects of Insufficient Lining Thickness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Test

2.1. Similar Material

2.2. Loading Equipment

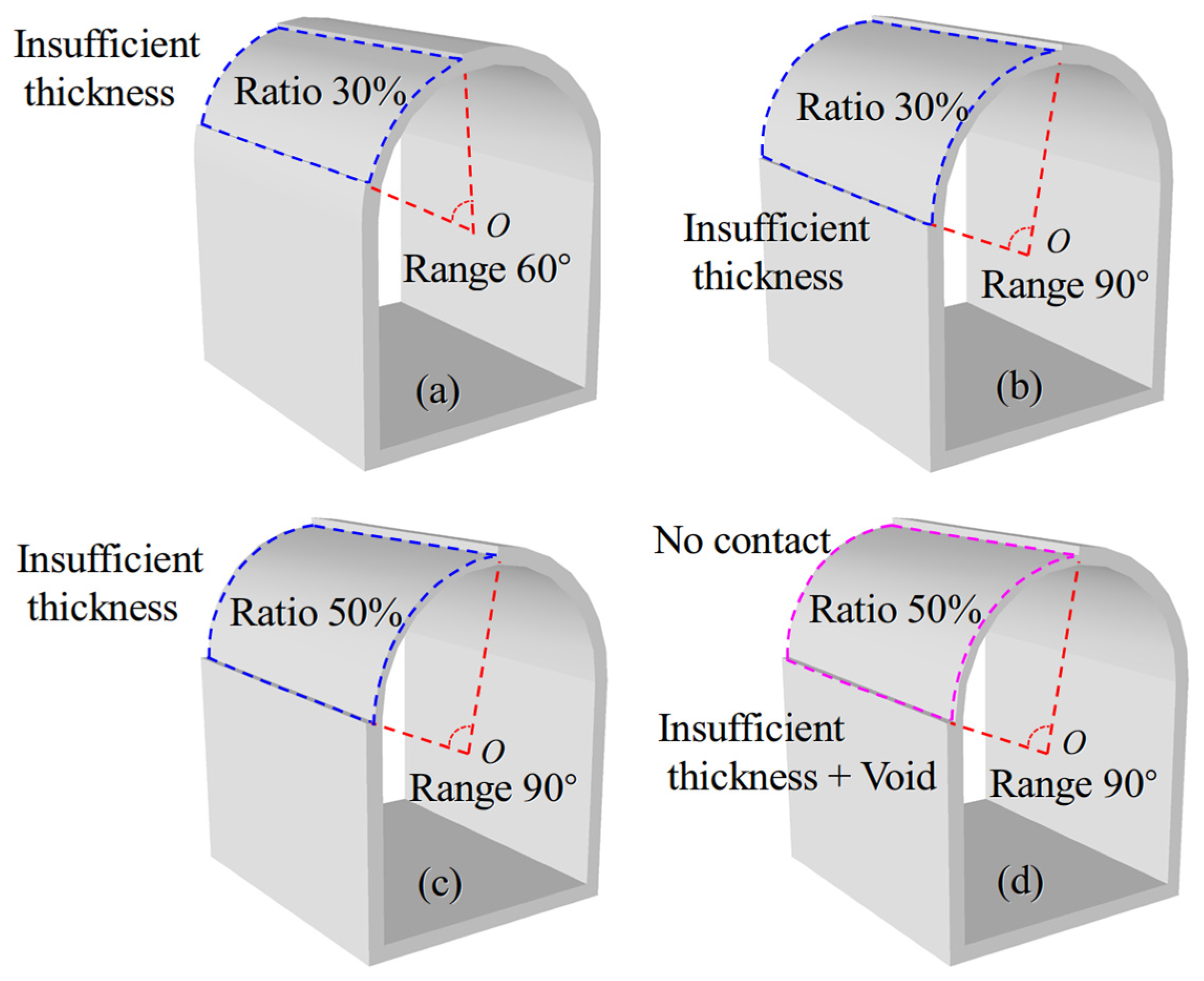

2.3. Design of Experimental Scheme

3. Experimental Results

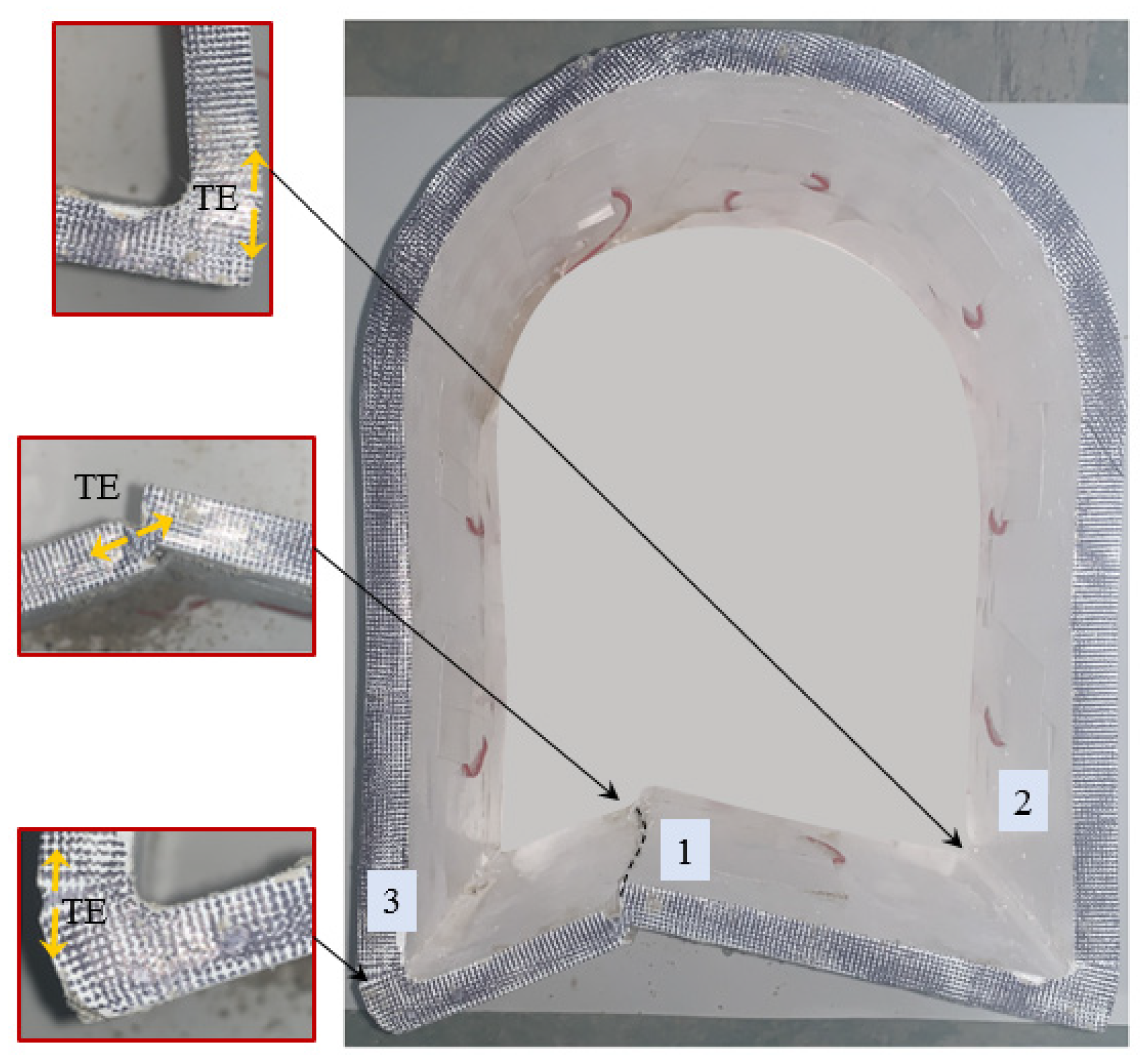

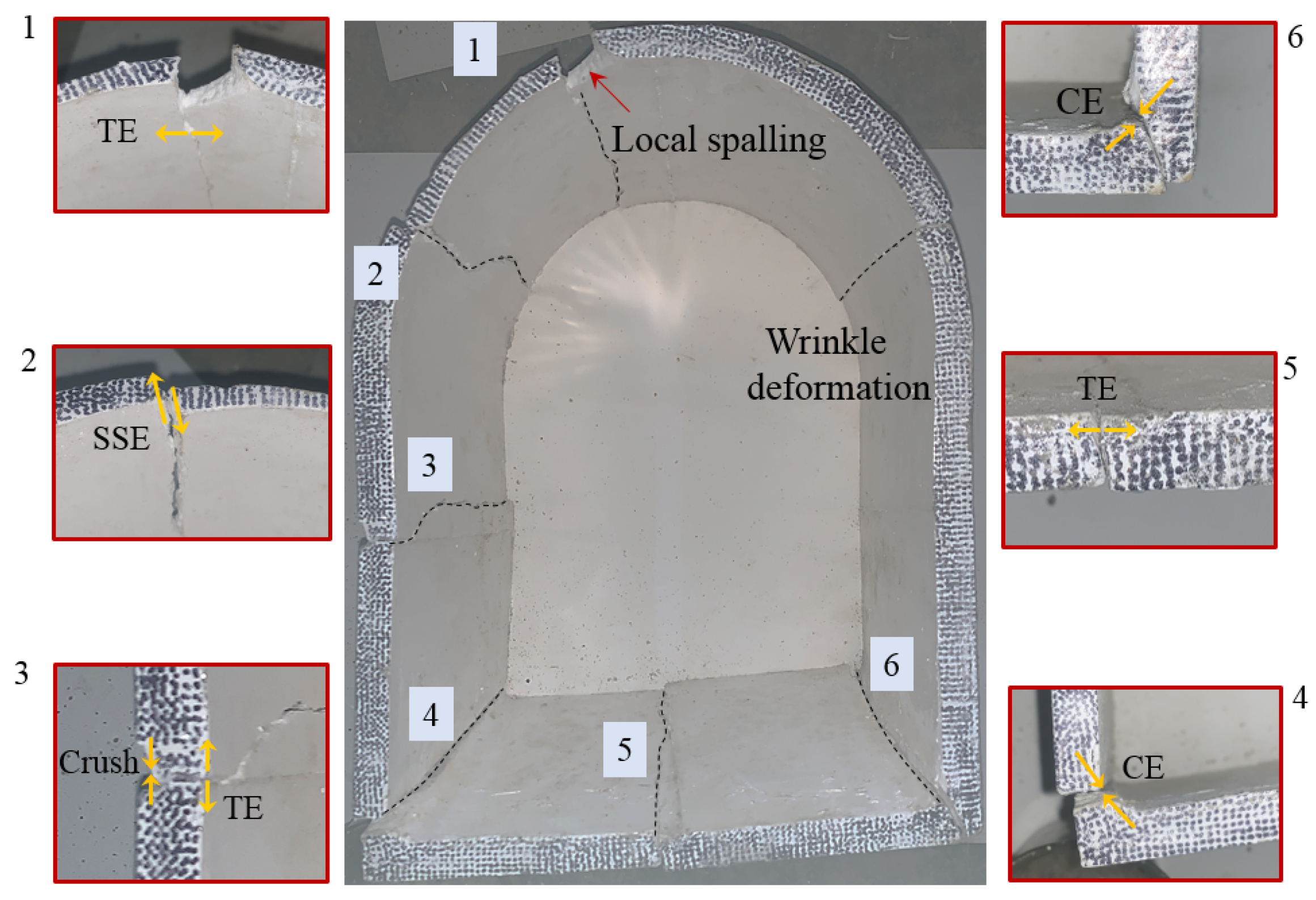

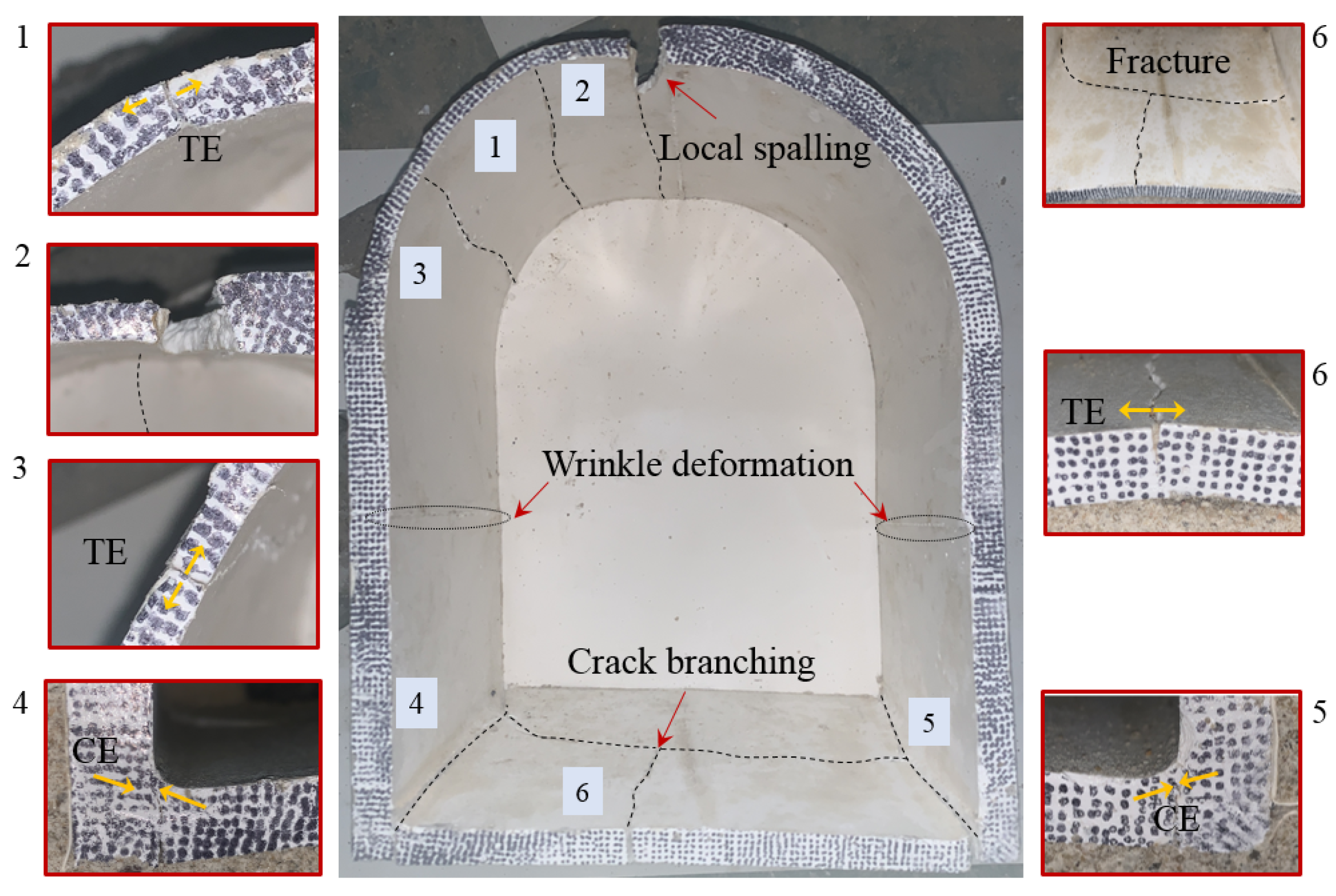

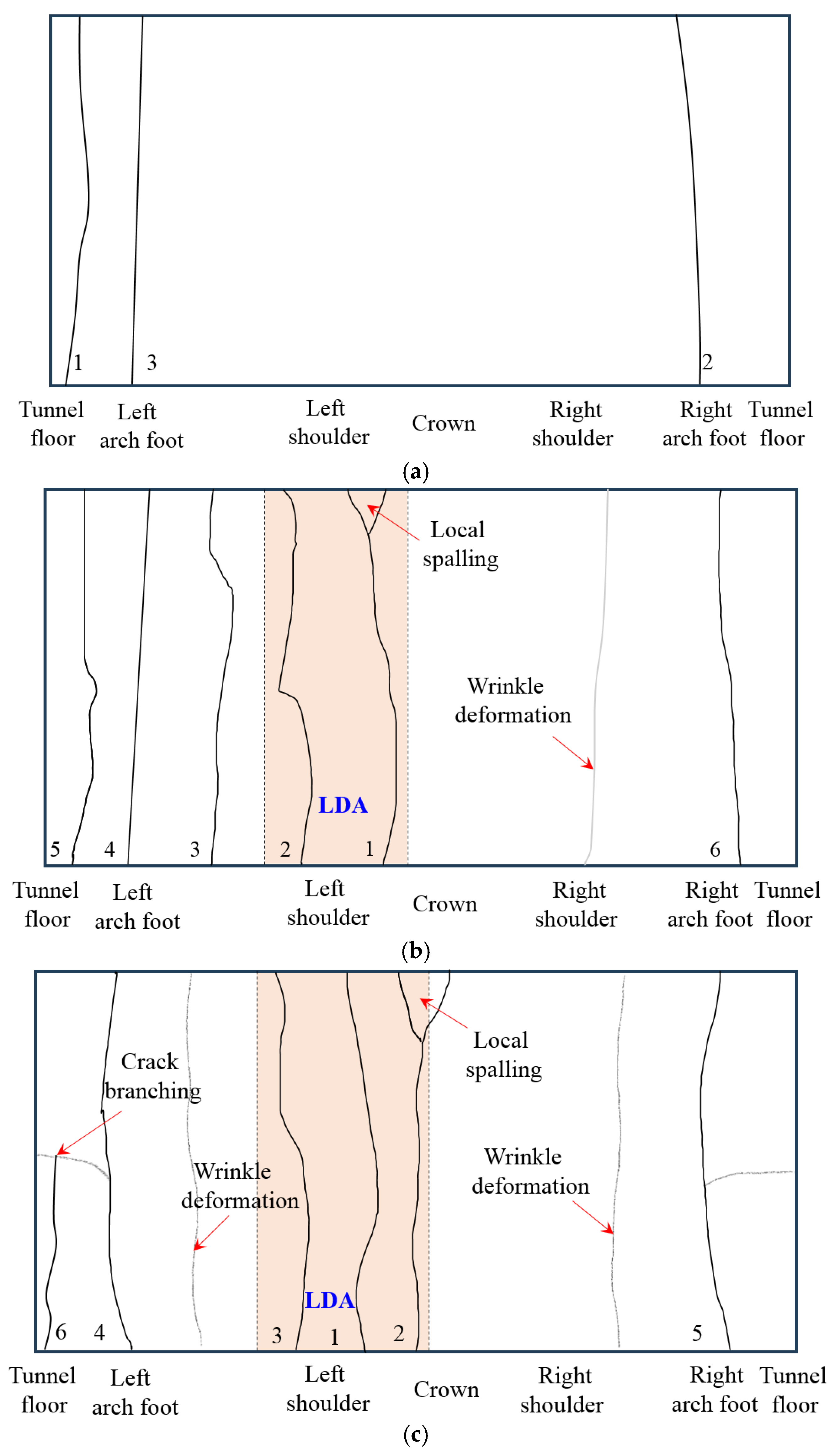

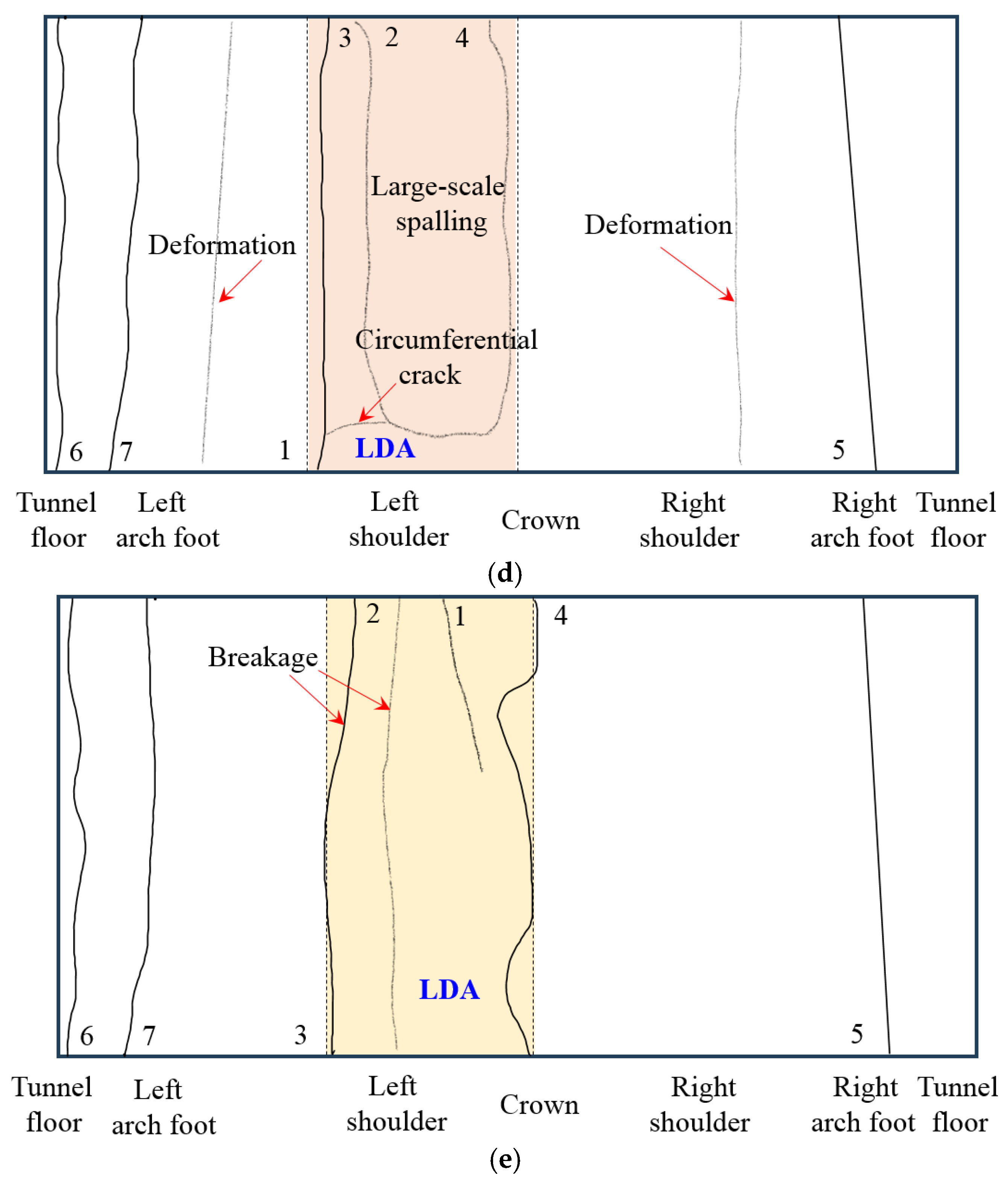

3.1. Fracture Characteristics

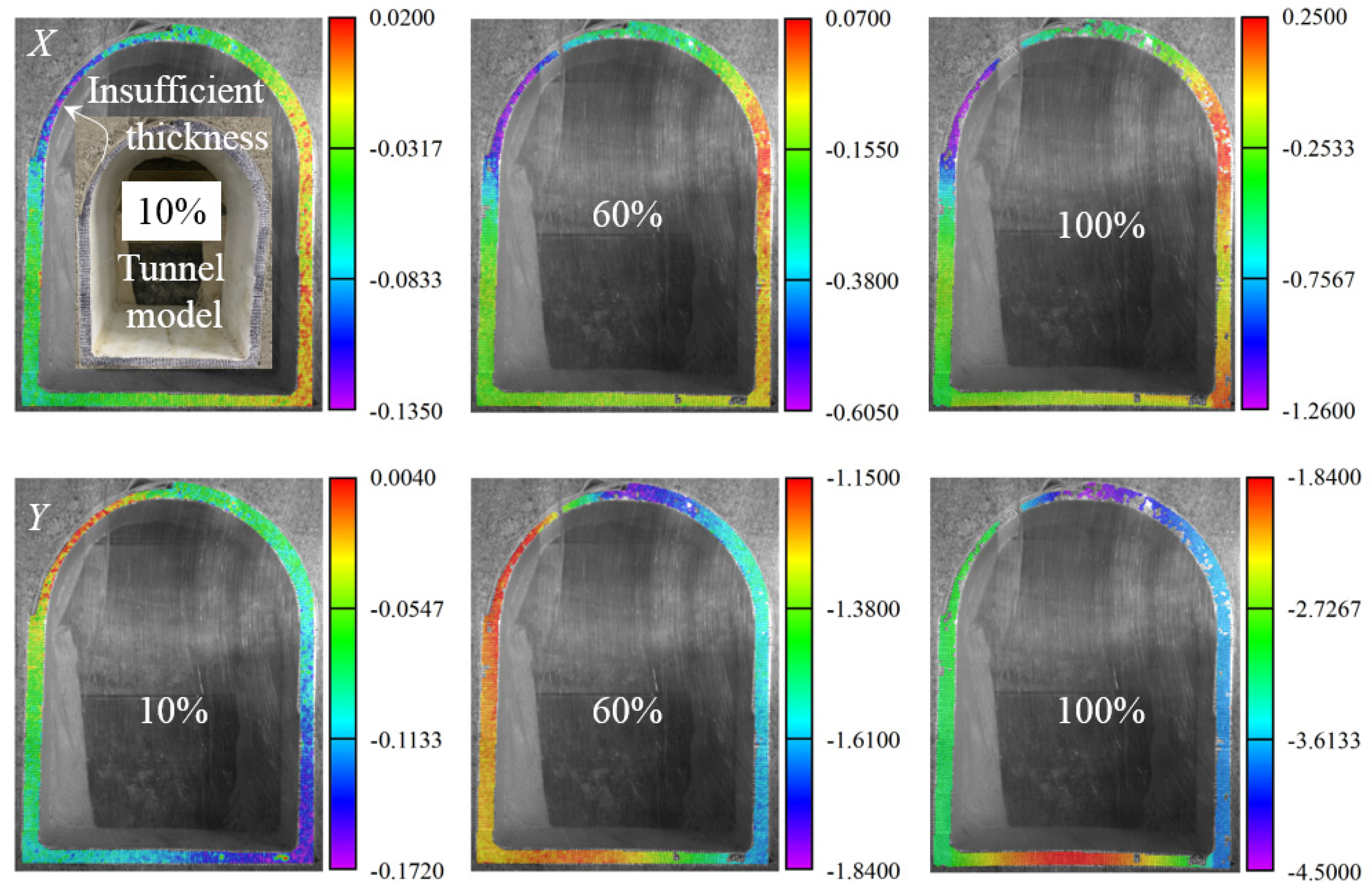

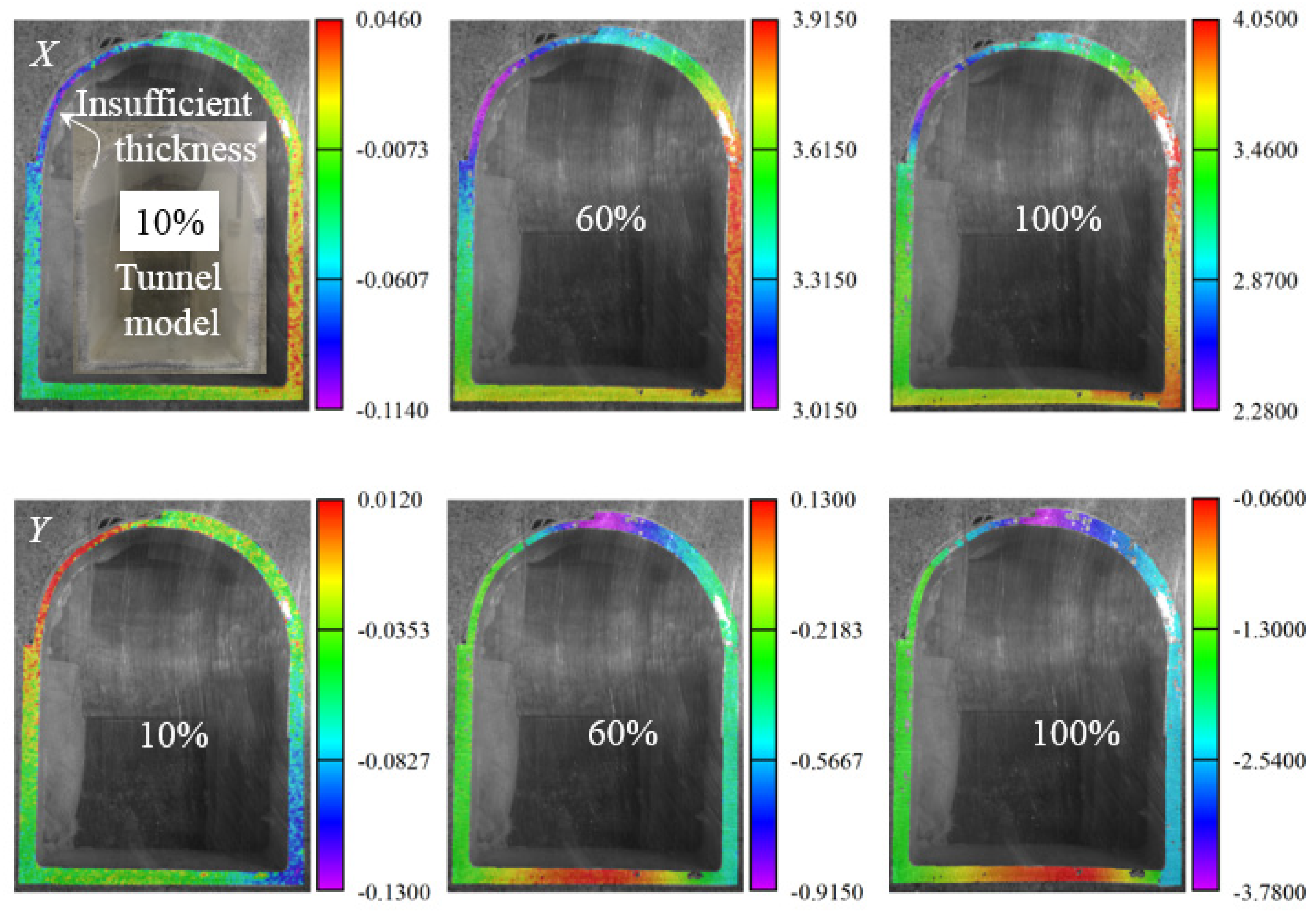

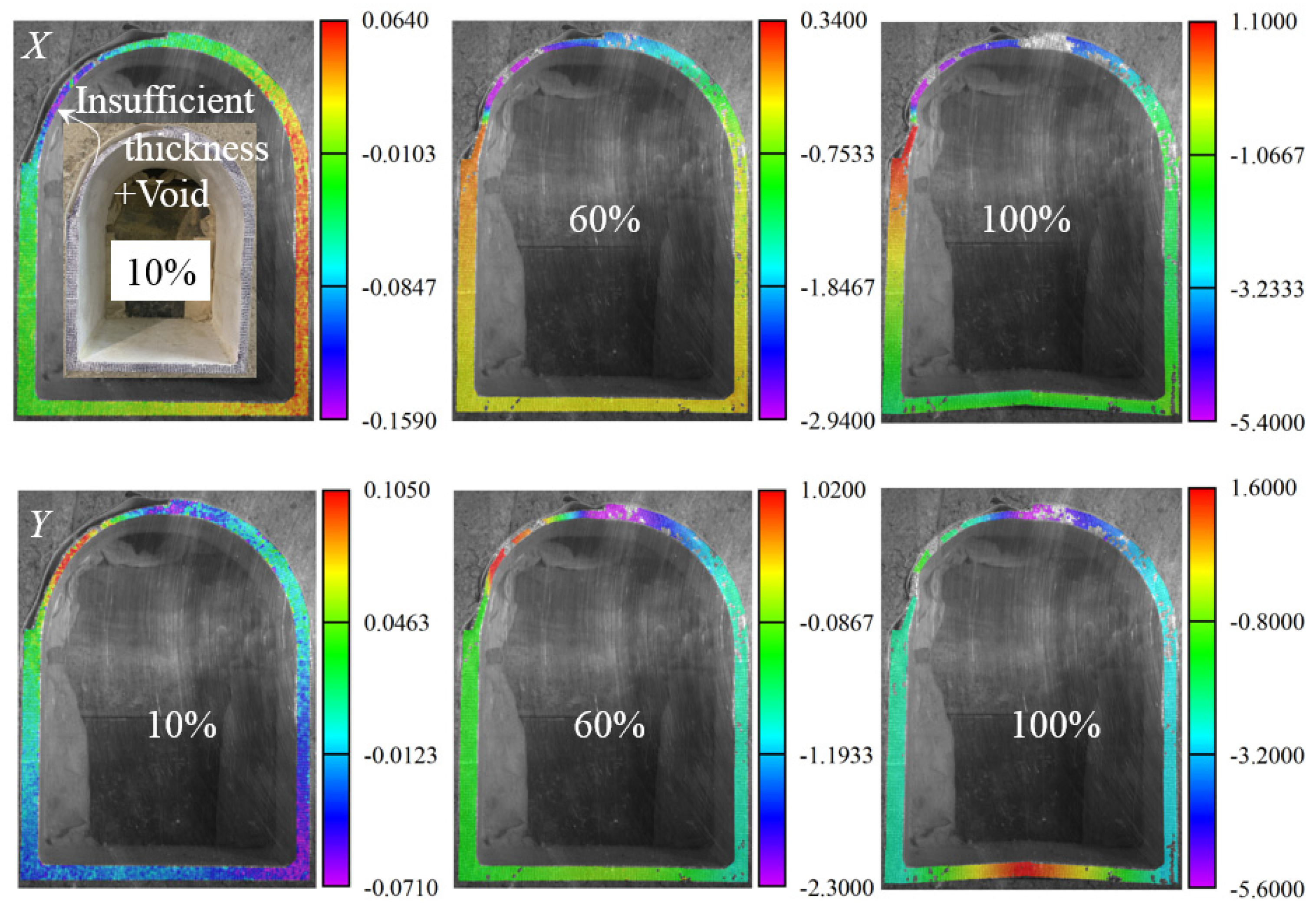

3.2. Deformation Behaviors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Insufficient lining thickness leads to significant changes in the lining failure mode of straight-wall tunnels. As the ratio of insufficient thickness increases or the range of insufficient thickness increases, the failure mode gradually becomes more complex. The area with insufficient lining thickness becomes the core area of fracture, accompanied by phenomena such as spalling and crushing.

- (2)

- Whether the defect comes into contact with the surrounding rock significantly affects the failure characteristics. In cases where the defect does not come into contact with the surrounding rock, a combination of voids and insufficient thickness is formed, resulting in the superposition of stress concentration effects in the defect area. The tensile effect formed by the voids interacts with the shear failure caused by insufficient thickness, forming a relatively complex failure mode.

- (3)

- The ratio and range of insufficient lining thickness significantly alter the deformation characteristics of the straight-wall tunnel structure. In areas with insufficient thickness, the displacement changes are more obvious, which is prone to induce large deformation areas, and the deformation basically increases with the increase in the ratio and range of insufficient lining thickness.

- (4)

- The failure mechanism of lining structures with insufficient thickness begins with tensile-shear failure at defective areas, progressively propagates to compressive failure at the arch foot and tensile failure in the tunnel floor, ultimately forming a collaborative failure mode through the combined action of various components.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Chen, L.; Zhu, X.M.; Huang, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, Z.M. Mechanical characterization and dynamic fracture behavior of twin straight-wall-top-arch tunnels under impact loading. Theo. Appl. Fract. Mec. 2025, 139, 105042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, X.S.; Cong, Y.; Li, Q.Q.; Pan, Y.Q.; Ding, X.L. Critical Failure Characteristics of a Straight-Walled Arched Tunnel Constructed in Sandstone under Biaxial Loading. Processes 2024, 12, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.Y.; Jia, W.R.; Xie, J.S.; Feng, Z.N.; Tian, S.S.; Li, S.G. Study on the disaster mechanism and treatment measures of invert uplift cracking of in-service tunnel-A case research. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 471, 140772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Kojima, Y. Tunnel maintenance in Japan. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2003, 18, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; He, N.N.; Xu, F.; Du, Y.L.; Xu, H.B. Visual detection method of tunnel water leakage diseases based on feature enhancement learning. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 153, 106009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.J.; Wang, F.; Hu, Q.F.; Hang, H.W.; Zuo, J.P.; Tian, C.; Zhang, D.M. Structural responses and treatments of shield tunnel due to leakage: A case study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 103, 103471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Xu, F.; Du, Y.L.; Liu, X.T.; Ma, J.W.; Zhu, S.N. Evaluation method of tunnel cracking disease under biased pressure based on enhanced image fractal features. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 441, 137530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.J.; Fei, R.Z. Optimisation Study on Crack Resistance of Tunnel Lining Concrete Under High Ground Temperature Environment. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2022, 40, 3985–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.B.; Chai, J.F. Development Status of Disease Detection, Monitoring, Evaluation and Treatment Technology of railway Tunnels in Operation. Tunn. Constr. 2019, 39, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lei, M.F.; Li, W.H. Safety influence of operating highway tunnel caused by sturcture disease. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2011, 8, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.J. The Influence of Poor Contact State between Tunnel Lining and Surrounding Rock on the Safety of Lining Structure. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Su, J.; Xu, Y.J.; Min, B. Experimental and numerical investigation the effects of insufficient concrete thickness on the damage behaviour of multi-arch tunnel. Structures 2021, 33, 2628–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Li, Y.L.; Wei, M.; Duan, J.C. Discussion on causes of and preventive measures against tunnel lining voids and inadequate thickness. Modern Tunn. Technol. 2019, 56, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Xie, X.Y.; Zhai, J.L.; Zhou, B.; Huang, C.F.; Wang, C. Tunnel lining defects identification using TPE-CatBoost algorithm with GPR data: A model test study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 157, 106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Jiang, Y.J.; Wang, G.; Liu, C.Z.; Koga, D. Review of health inspection and reinforcement design for typical tunnel quality defects of voids and insufficient lining thickness. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 137, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, H.K. Experimental research on tunnel health criterion of deficiency in lining thickness. Rock Soil Mech. 2011, 32, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.P.; Zhang, X.; Feng, G.; Zhang, D.L. Influence of insufficient lining thickness on the safety of a tunnel structure. Modern Tunn. Technol. 2017, 54, 137–143, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhu, J.L.; Huang, S.L.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, Y.B.; Lei, S.D.; Zhou, P. Numerical study on tunnel deformation under local thickness reduction in tunnel linings and destruction prediction. China J. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 46, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, Z.; Feng, W.L.; Yang, H.Y.; Xiang, Y.H. Evolution of structural safety for tunnel arch crown linings under the coupled influence of void and insufficient thickness. Structures 2024, 68, 107125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.M.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.Y.; Song, Z.H.; Wang, X.M.; Peng, X.Y. Analysis of the influence of the thickness insufficiency in secondary lining on the mechanical properties of Double-layer lining of shield tunnel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 141, 106663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.S.; Lv, G.H.; Wang, K.; Han, B.; Xie, Q.Y. Study on Crack Development of Concrete Lining with Insufficient Lining Thickness Based on CZM Method. Materials 2021, 14, 7862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W.; Jiang, Y.J.; Li, N.B.; Luan, H.J.; Wu, X.L. Study on cracking behavior of tunnel linings with the diseases of void and lining insufficient thickness. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 861, 042113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Shi, Y.; Sun, R.; Yang, J.S. Damage behavior and maintenance design of tunnel lining based on numerical evaluation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 109, 104209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.P. Study on the Tunnel Structure Safety under the Impact of the Lining Thickness Deficiency. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, J.H.; Che, Z.J.; Li, W.H.; Zhang, S.L.; Yuan, C.F.; Cheng, D.G. Study on the structural cracking mechanism under the influence of voids behind straight-wall tunnel lining. J. Qingdao Univ. Technol. 2022, 43, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Q.Y.; Zhou, S.W. Fracture process analysis of polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete based on DIC. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2024, 52, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.X.; Ren, G.F.; Li, X.P.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.W.; Xu, C.; Zhang, C.R. Study on mechanical properties and failure behavior of jointed gypsum rock under uniaxial compression using AE and DIC techniques. Results in Eng. 2025, 27, 106024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.T.; Liu, Q.R.; Zhang, Y.S.; Huang, Z.J. Identifying rock fracture precursor by multivariate analysis based on the digital image correlation technique. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 2023, 126, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Y.; Zhu, Q.Q.; Zhou, Z.L.; Li, X.B.; Ranjith, P.G. Fracture analysis of marble specimens with a hole under uniaxial compression by digital image correlation. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2017, 183, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.Y.; Liu, Y.Z.; Ren, X.C.; Pan, B. Panoramic deformation measurement and crack identification in concrete with deep-learning-based multi-camera DIC. Measurement 2025, 256, 118133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.S.; Zhou, Z.F.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.Q.; Hou, X. Evaluation of low-temperature fracture and damage of asphalt concrete using SCB test combined with DIC. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 321, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Gao, D.Y.; Ding, C.; Wang, L.; Tang, J.Y. Whole process analysis on splitting tensile behavior and damage mechanism of 3D/4D/5D steel fiber reinforced concrete using DIC and AE techniques. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 457, 139295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.T.; Zhang, Z.X.; Zhu, Y.F.; Huang, X.; Zhuang, Q.W. Capturing the cracking characteristics of concrete lining during prototype tests of a special-shaped tunnel using 3D DIC photogrammetry. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. En. 2018, 22, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Z.J. Study on the Safety of the Straight Wall Tunnel under the Condition of Void behind the Lining. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, M.; Xie, H.; He, C.; Fang, Y.; Wang, S. Model test study of the mechanical characteristics of the lining structure for an urban deep drainage shield tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 91, 103014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B. Study on the Cracking Characteristic of Asymmetric Double-Arch Tunnel Linings and Its Influence on Structural Bearing Capacity. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanical | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Bulk Density (kN/m3) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Prototype | 30.0 | 21.0 | 2.01 | 25 | 0.2 |

| Material | 150 Mesh Barite Powder | 600 Mesh Barite Powder | 10 Mesh Quartz Sand | 40 Mesh Quartz Sand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight ratio | 16.2 | 48.5 | 21.6 | 10.7 |

| Materials | Elastic Modulus/GPa | Cohesion/ MPa | Bulk Density/ kN/m3 | Internal Friction Angle/° | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Prototype | 0.85 | 180 | 18 | 22 | 0.32 |

| Model | 0.021 | 4.6 | 18 | 22 | 0.32 |

| Cases | Ratio of Insufficient Lining Thickness | Defect Range | Contact Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case1 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| Case 2 | 0.3 | 60° | Yes |

| Case 3 | 0.3 | 90° | Yes |

| Case 4 | 0.5 | 90° | Yes |

| Case 5 | 0.5 | 90° | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, W.; Du, X.; Du, Y.; Yue, J.; Huang, B.; Liu, H. Experimental Investigation on Fracture Behaviors of Straight-Wall Tunnels with Defects of Insufficient Lining Thickness. Processes 2025, 13, 3909. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123909

Han W, Du X, Du Y, Yue J, Huang B, Liu H. Experimental Investigation on Fracture Behaviors of Straight-Wall Tunnels with Defects of Insufficient Lining Thickness. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3909. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123909

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Wei, Xuze Du, Yihan Du, Jiapeng Yue, Bo Huang, and Hui Liu. 2025. "Experimental Investigation on Fracture Behaviors of Straight-Wall Tunnels with Defects of Insufficient Lining Thickness" Processes 13, no. 12: 3909. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123909

APA StyleHan, W., Du, X., Du, Y., Yue, J., Huang, B., & Liu, H. (2025). Experimental Investigation on Fracture Behaviors of Straight-Wall Tunnels with Defects of Insufficient Lining Thickness. Processes, 13(12), 3909. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123909