4.1. Injection Model Establishment

① Continuity Equation

In a flow field, the difference between the mass inflow and outflow should be equal to the mass increase within the control volume, from which the continuity equation can be derived as follows:

Wherein,

—mass-averaged velocity;

—gas–liquid mixture density;

mass transfer.

and

can be obtained through Equations (5) and (6), respectively.

Wherein,

—volume fraction and density of phase (where k = 1, 2, 3 represent the aqueous phase, oil phase, and gas phase, respectively)

② Momentum Equation

The conservation of momentum is a universal law followed by fluids, meaning that the time rate of change in the momentum of a system is equal to the sum of the external forces acting on it. Although gas and liquid form two phases, the conservation of momentum can be applied to each phase separately, and then the momentum equation is obtained by summing over all phases as follows:

Wherein,

—Body force

—Viscosity of gas–liquid mixture

—Drift velocity; , other symbols are the same as before

③ Energy Equation

Applying the first law of thermodynamics to a system yields the expression for the energy equation:

Wherein,

—Effective thermal conductivity;

—Volumetric heat source; in this system, since volumetric heat sources are not considered, we can set .

④ Slip Velocity Equation

Slip velocity refers to the velocity of the secondary phase relative to the primary phase, and its expression is as follows:

The slip velocity and drift velocity have the following relationship:

Wherein,

—Slip velocity, secondary phase velocity, primary phase velocity, the remaining symbols are the same as before.

⑤ Governing Equation for the Volume Fraction of the Secondary Phase

Based on the mass conservation equation of the secondary phase, its governing equation for the volume fraction can be derived as follows:

Wherein,

—denote the volume fraction and density of the secondary phase, respectively.

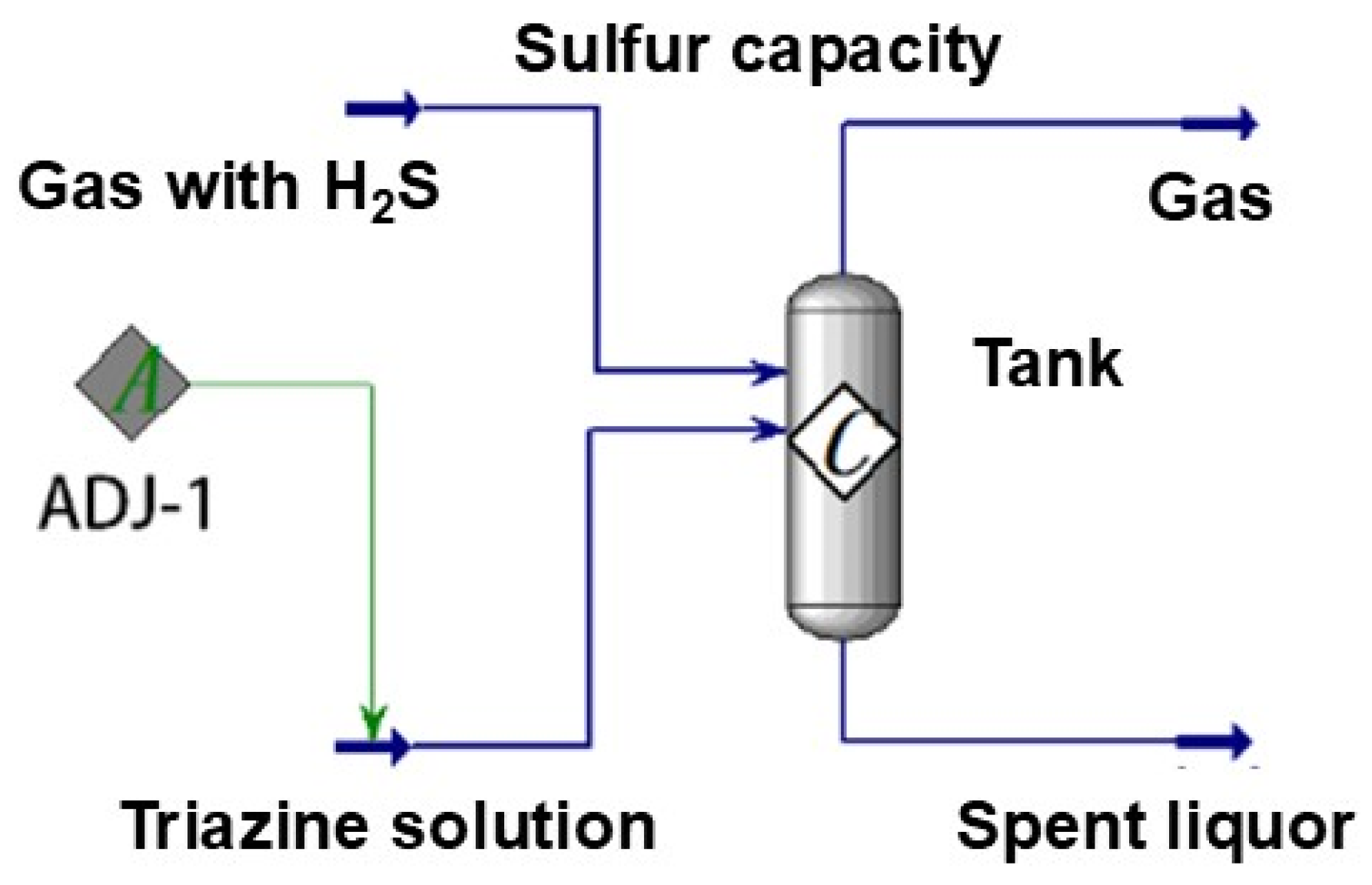

The computational model was solved using ANSYS FLUENT V2024 (Beijing Huanzhong Ruicheng Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). A Discrete Phase Model (DPM) was employed, treating the triazine droplets as a dilute phase (volume fraction < 1%) to neglect inter-particle interactions. Two-way coupling was implemented to capture momentum exchange between the continuous gas phase and the discrete liquid droplets.

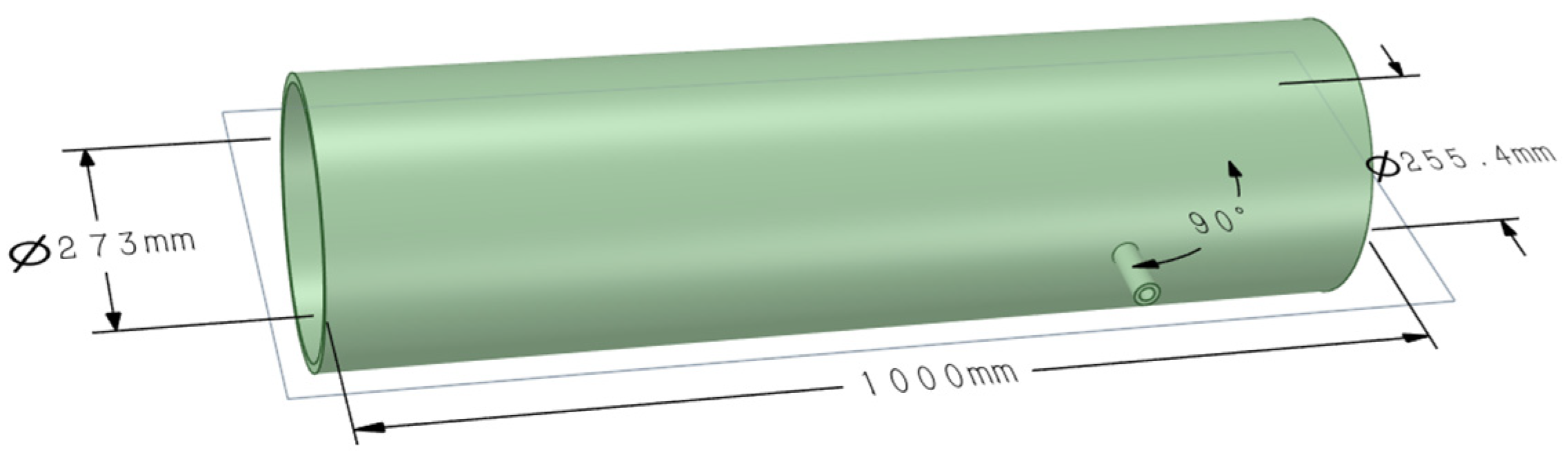

The velocity inlet boundary condition was specified with an inlet velocity of 15 m/s, consistent with field measurements, a turbulence intensity of 5% representative of pipeline flow, and a hydraulic diameter matching the pipeline’s inner diameter of 0.5 m. The outlet was configured as an outflow boundary to permit natural pressure development.

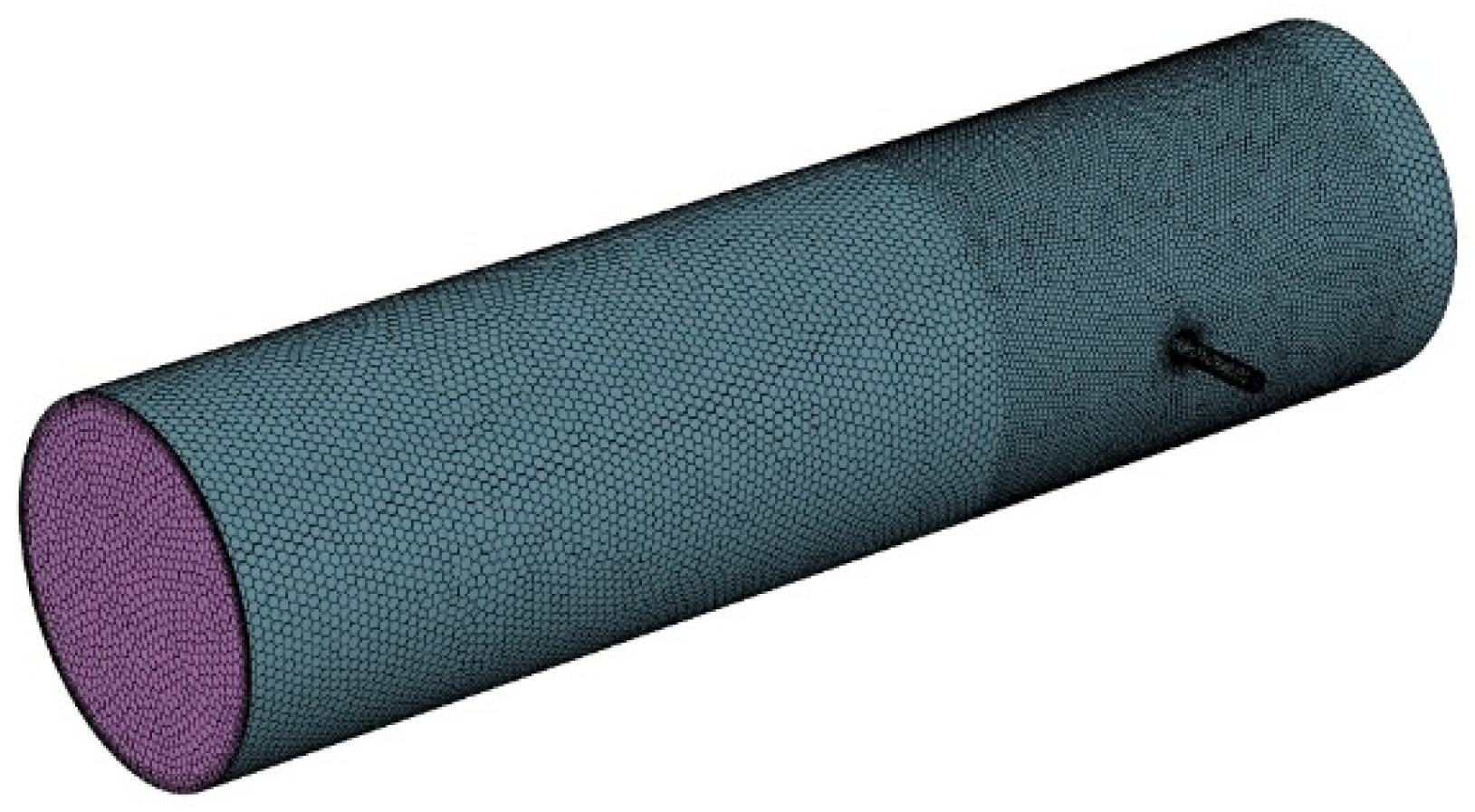

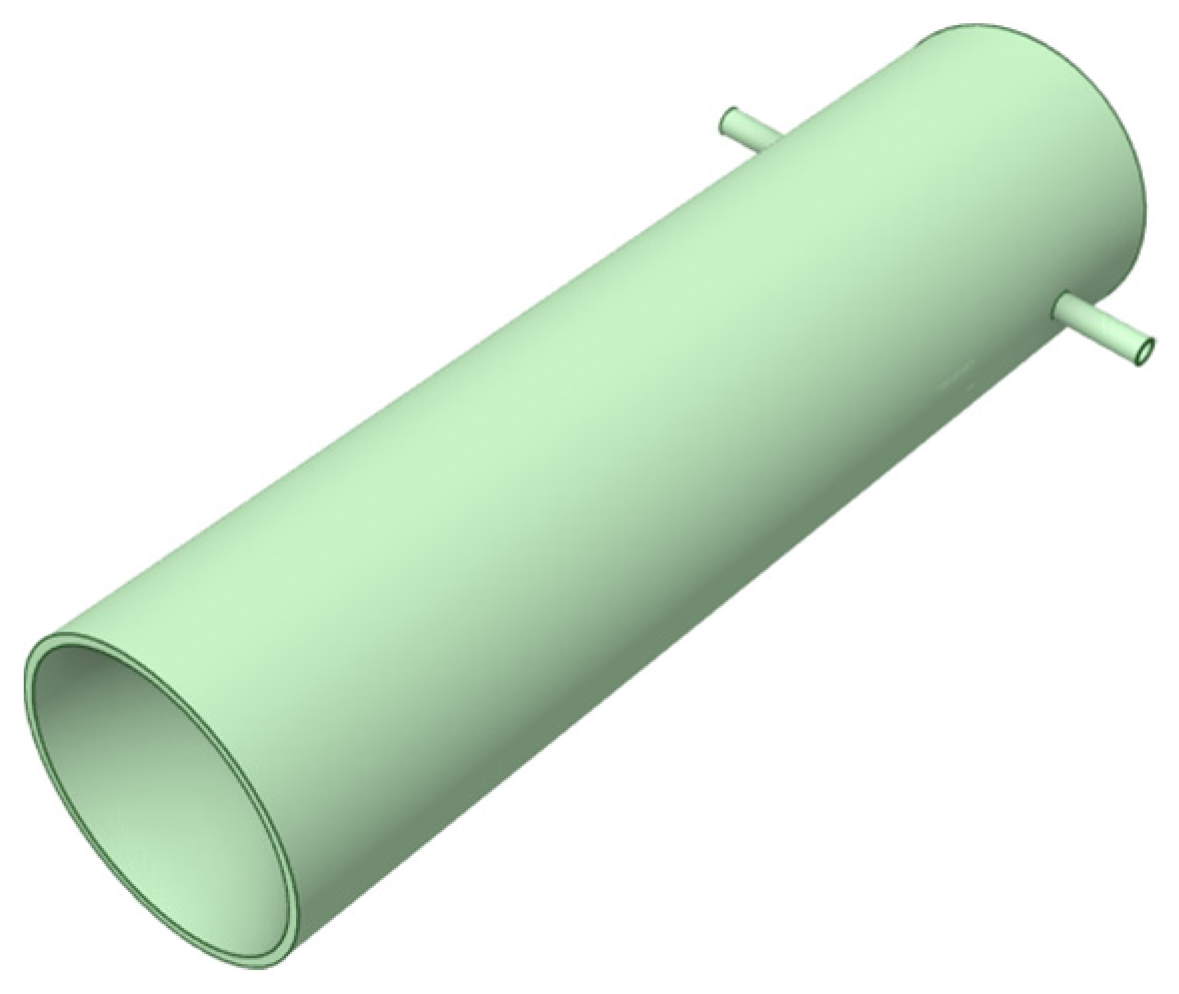

The geometric model and the resulting computational mesh are presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, respectively.

The geometric model and mesh generation results are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, respectively. Four sets of structured grids were generated using ANSYS FLUENT V2024, with refinement in the nozzle jet region to capture the high-gradient flow field. The grid parameters are shown in

Table 3.

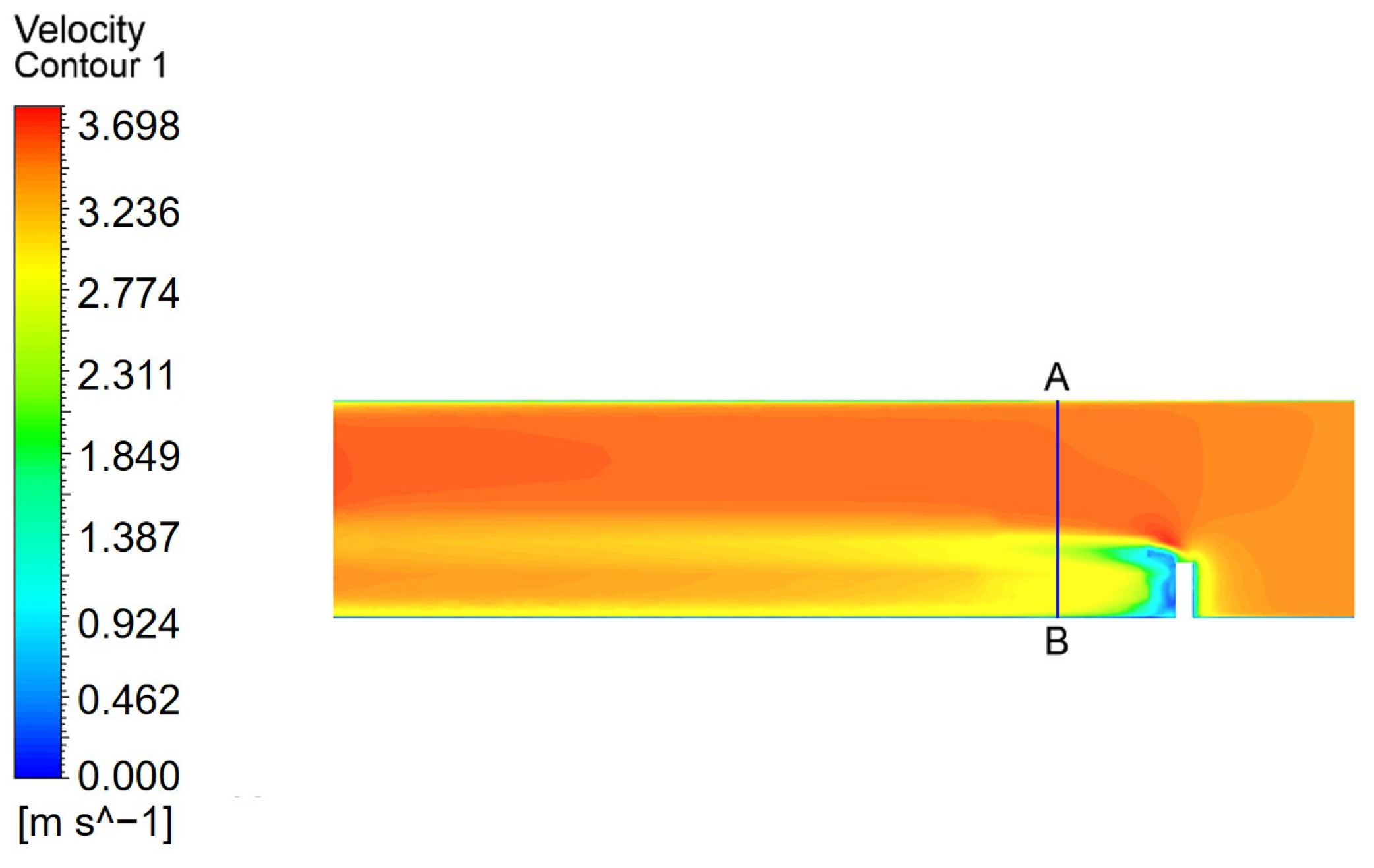

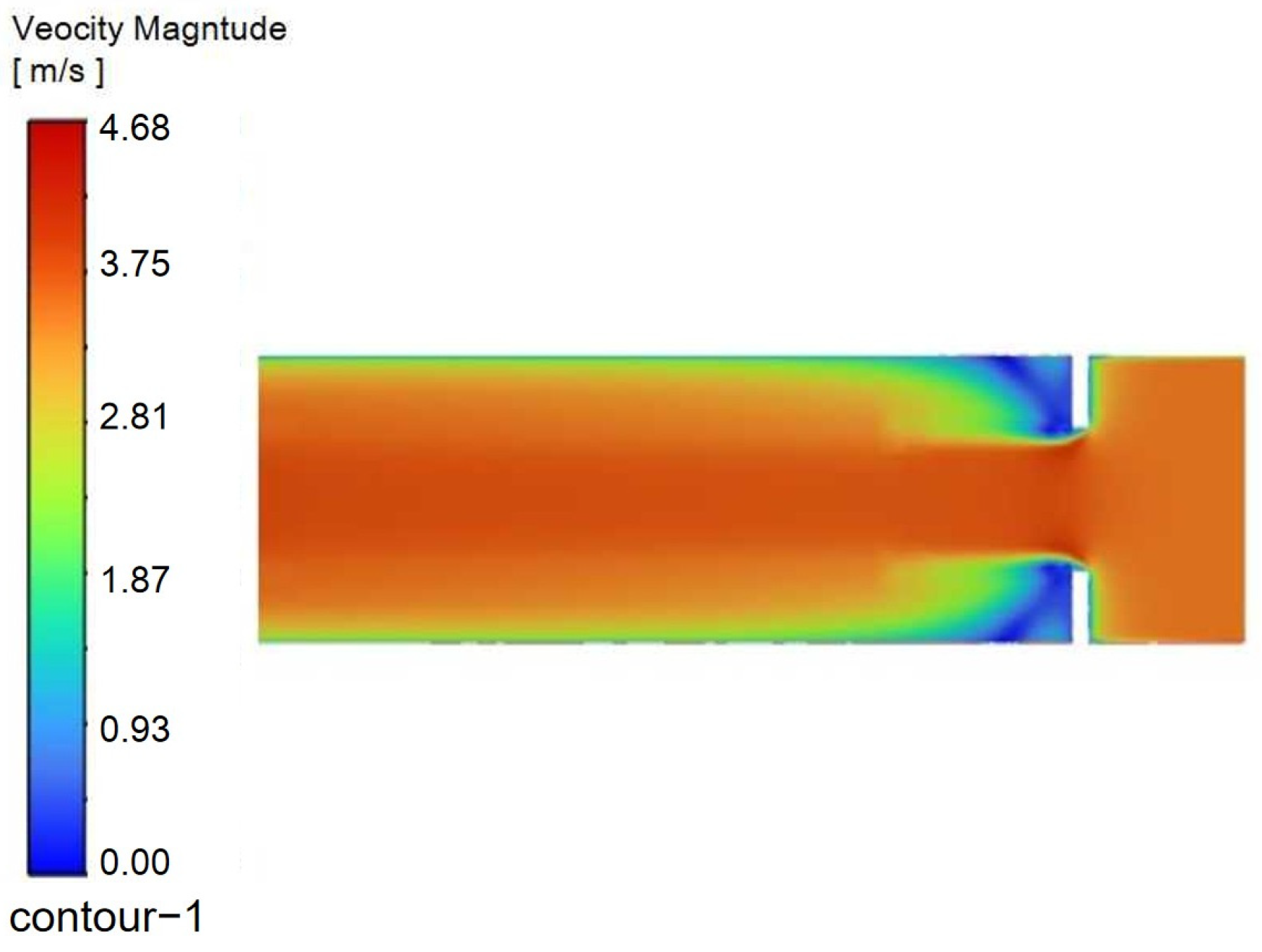

A straight-line AB was drawn at the position where the velocity changes in the flow domain, and the velocity distribution along this line was used as the convergence curve. The distance between line AB and the nozzle axis is 150 mm. The convergence curve of the velocity distribution within the watershed is shown in

Figure 10.

The velocity distribution profiles along line AB were computed for different grid configurations. The results from the Fine Grid and Finest Grid schemes show nearly overlapping curves, indicating that further mesh refinement has a negligible influence on the velocity field. Therefore, the Fine Grid resolution was selected for all subsequent simulations to balance accuracy and computational efficiency.

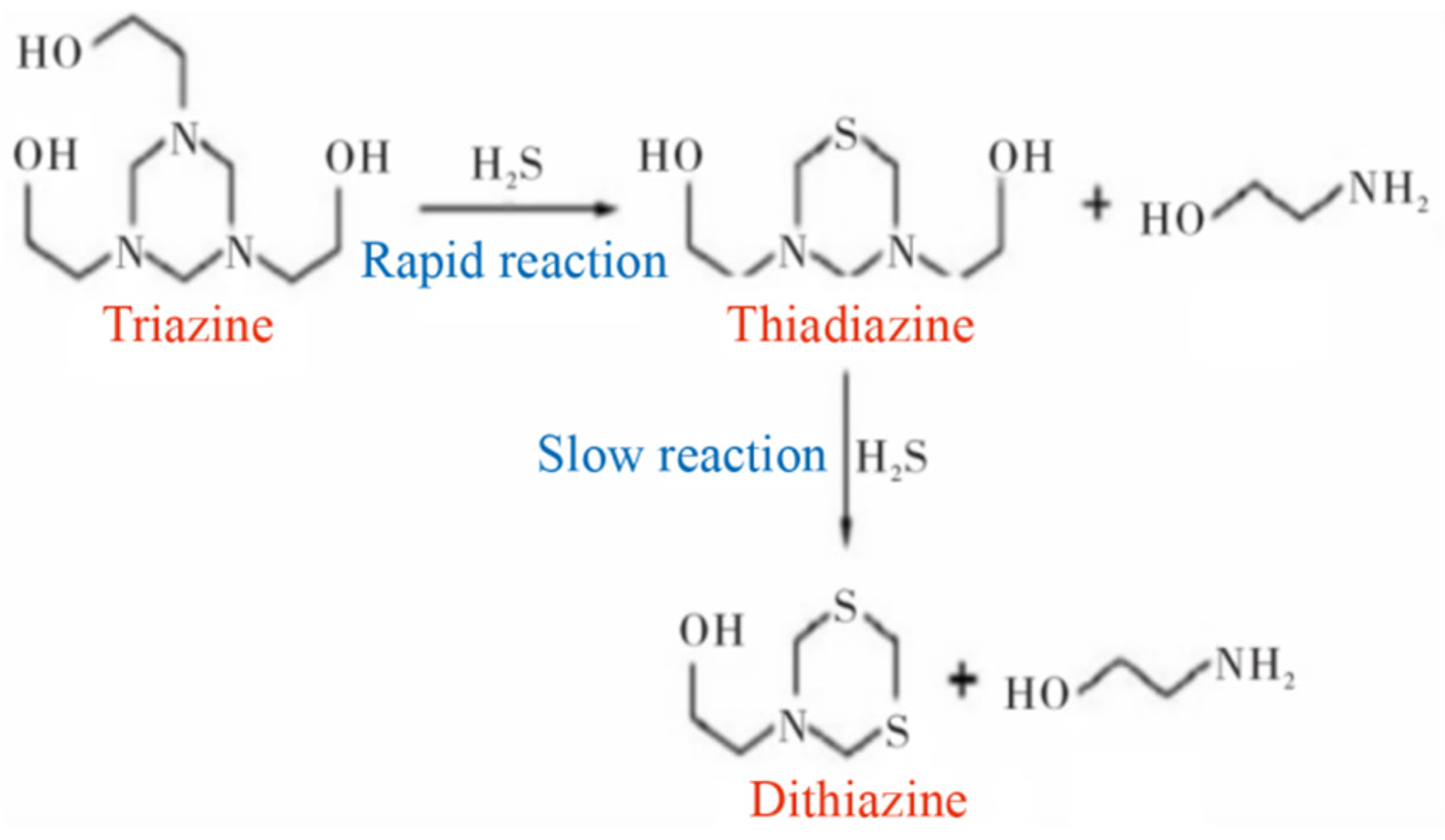

Triazine-based H2S removal constitutes a gas–liquid mass transfer and reaction process, in which H2S diffusion from the gas phase to the droplet surface typically acts as the rate-limiting step. The primary goal of the CFD simulation is to optimize the injection strategy so as to maximize gas–liquid interfacial area—achieved by reducing the Sauter mean diameter (D32)—and to improve droplet distribution uniformity, thereby lowering mass transfer resistance. It should be noted, however, that the current CFD model does not incorporate the chemical reaction kinetics between triazine and H2S. Therefore, the “good mixing” indicated by small D32 and uniform dispersion in the CFD results represents a necessary, yet insufficient, condition for guaranteeing effective desulfurization.

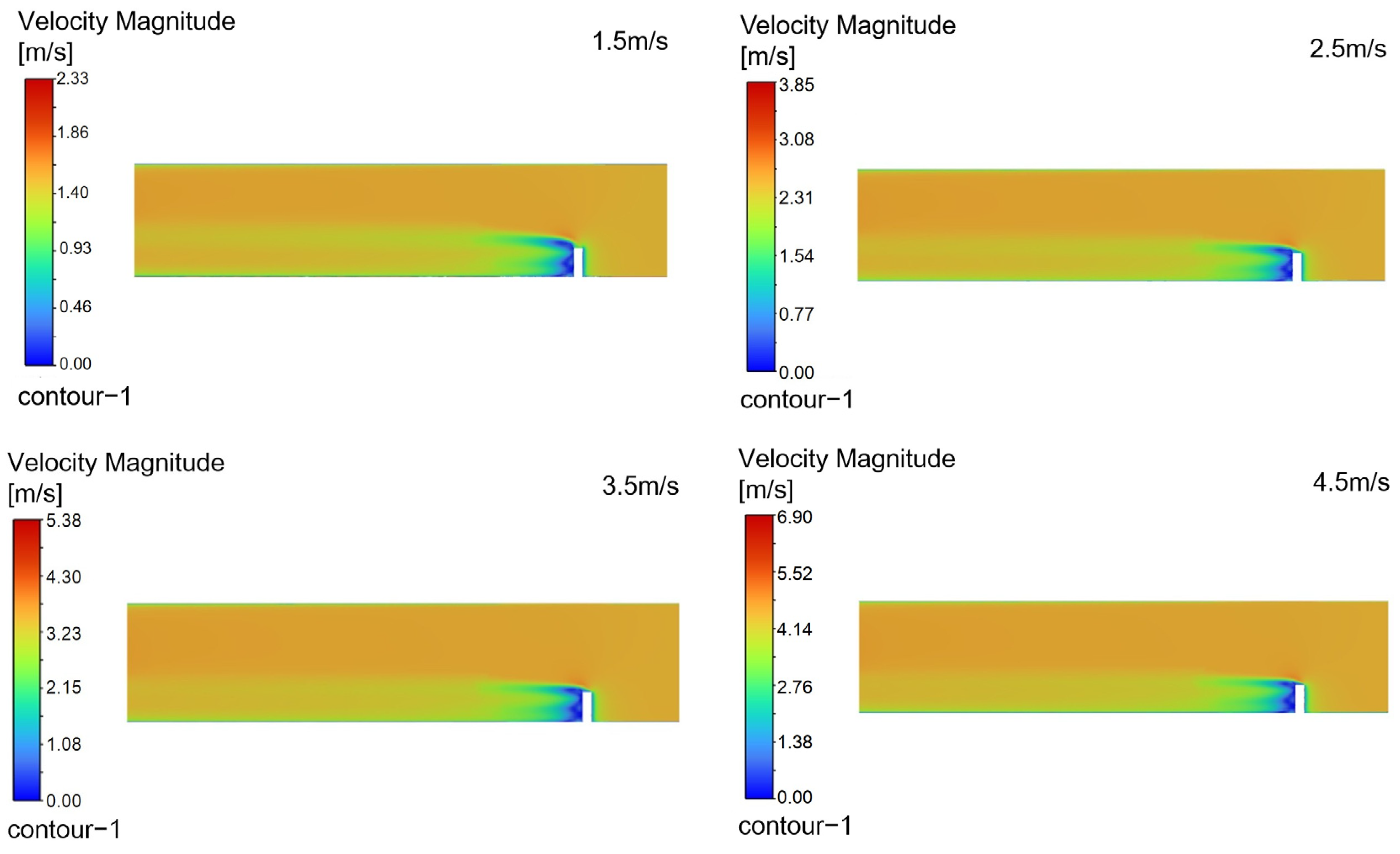

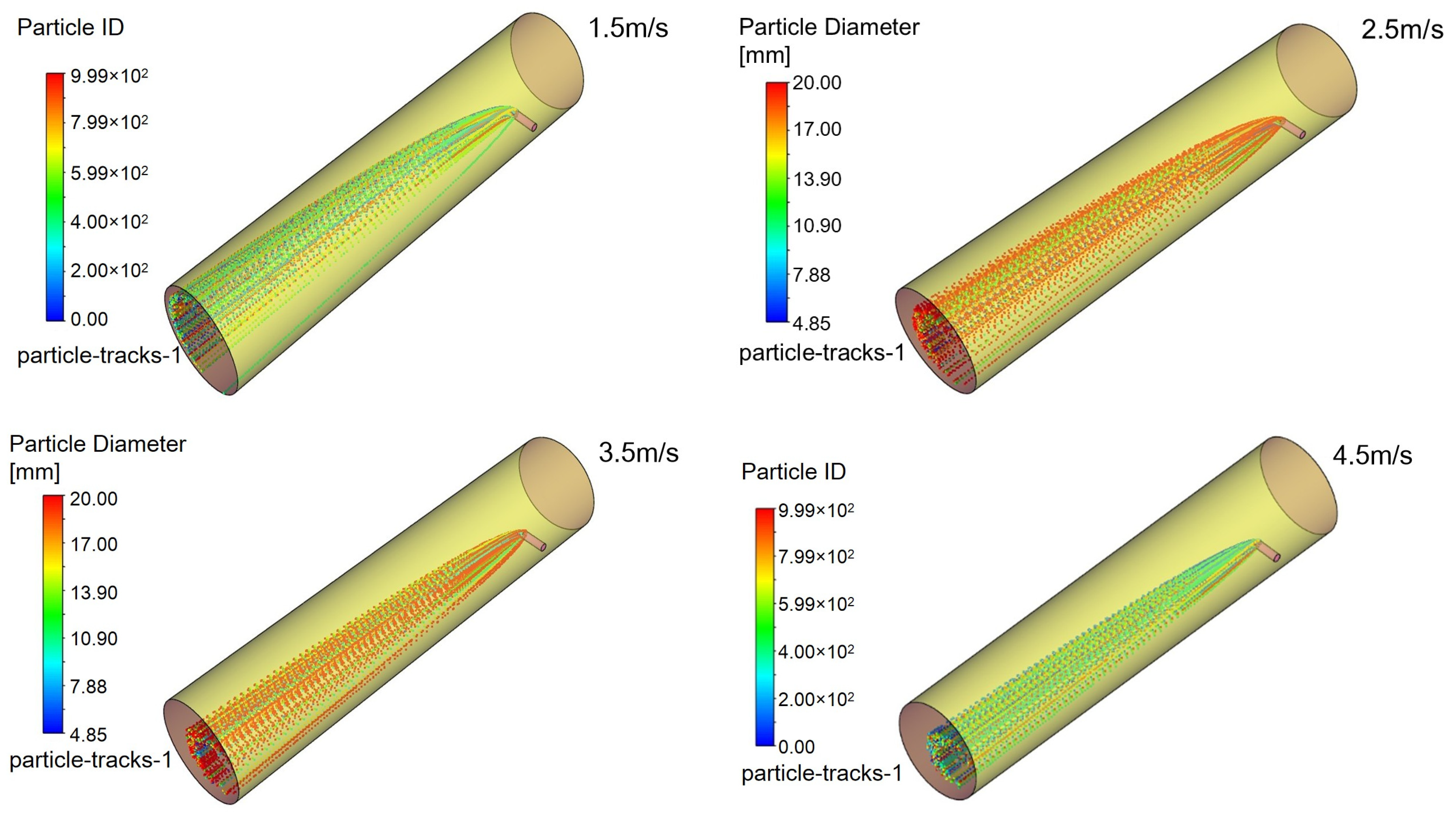

4.4. Influence of Nozzle Angle

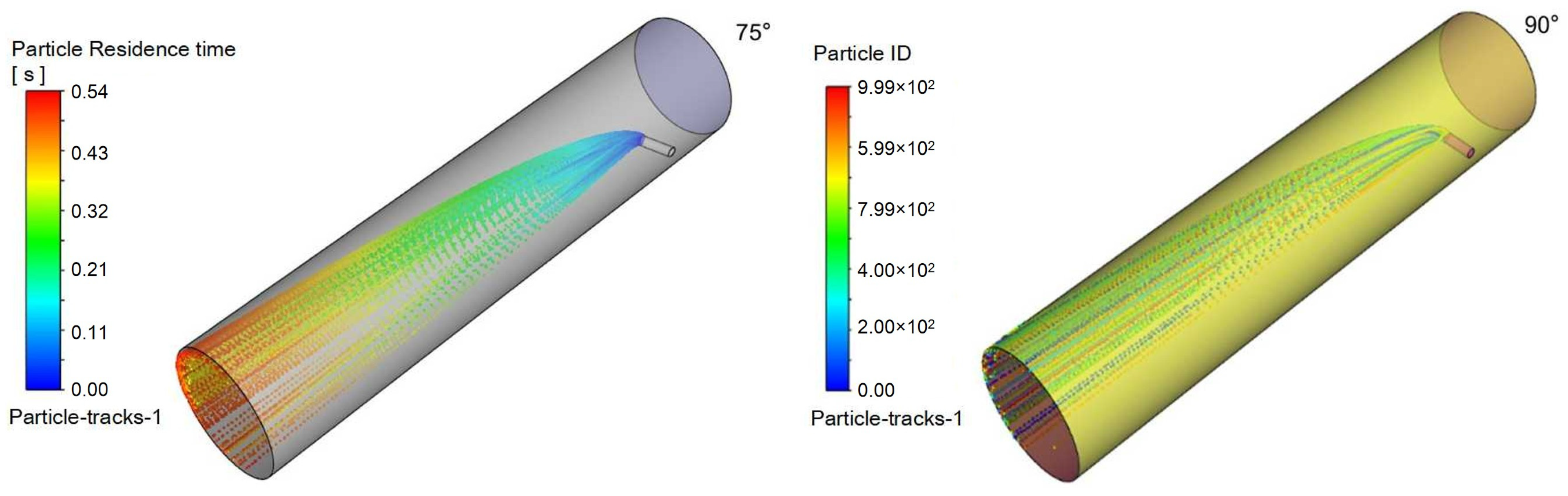

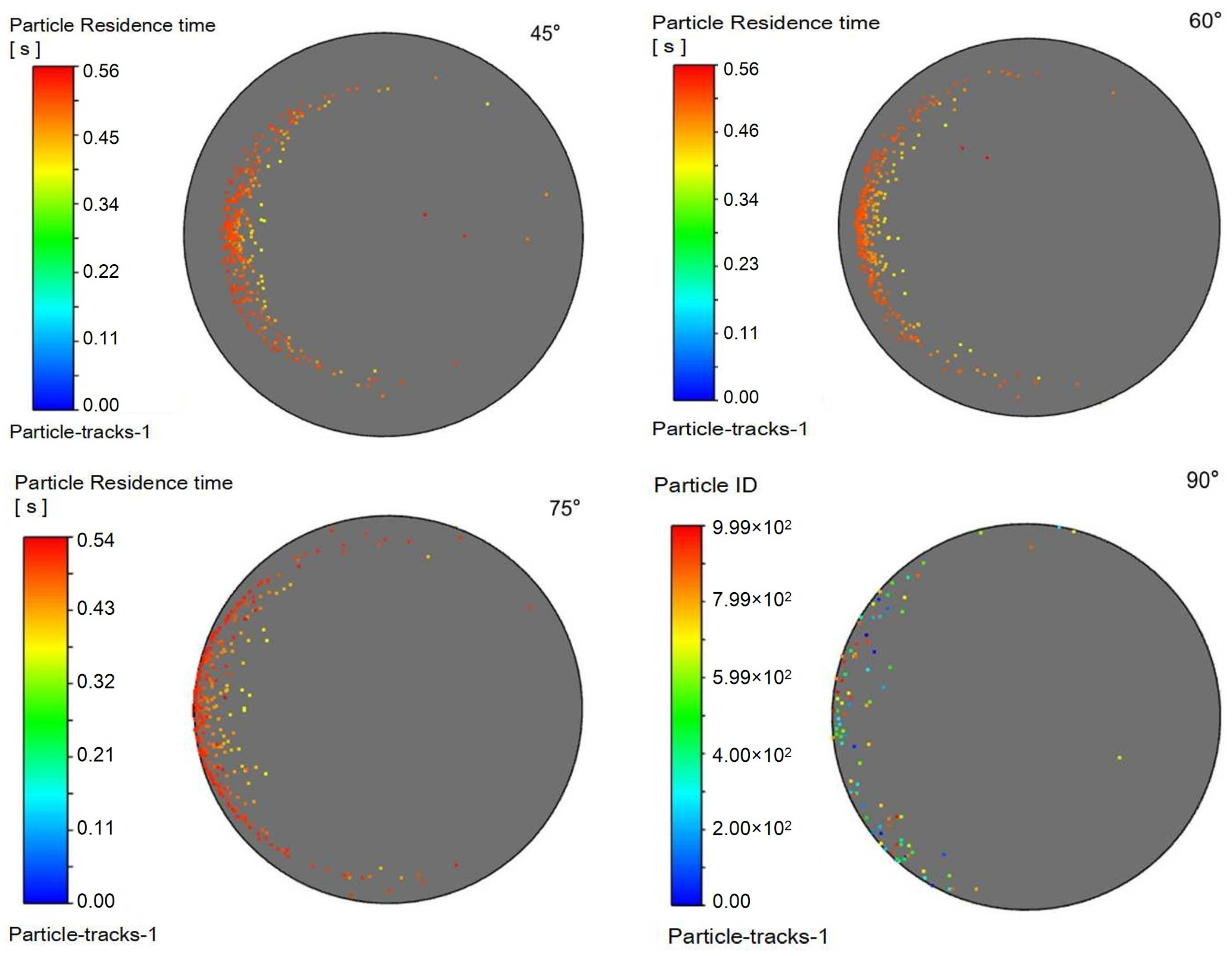

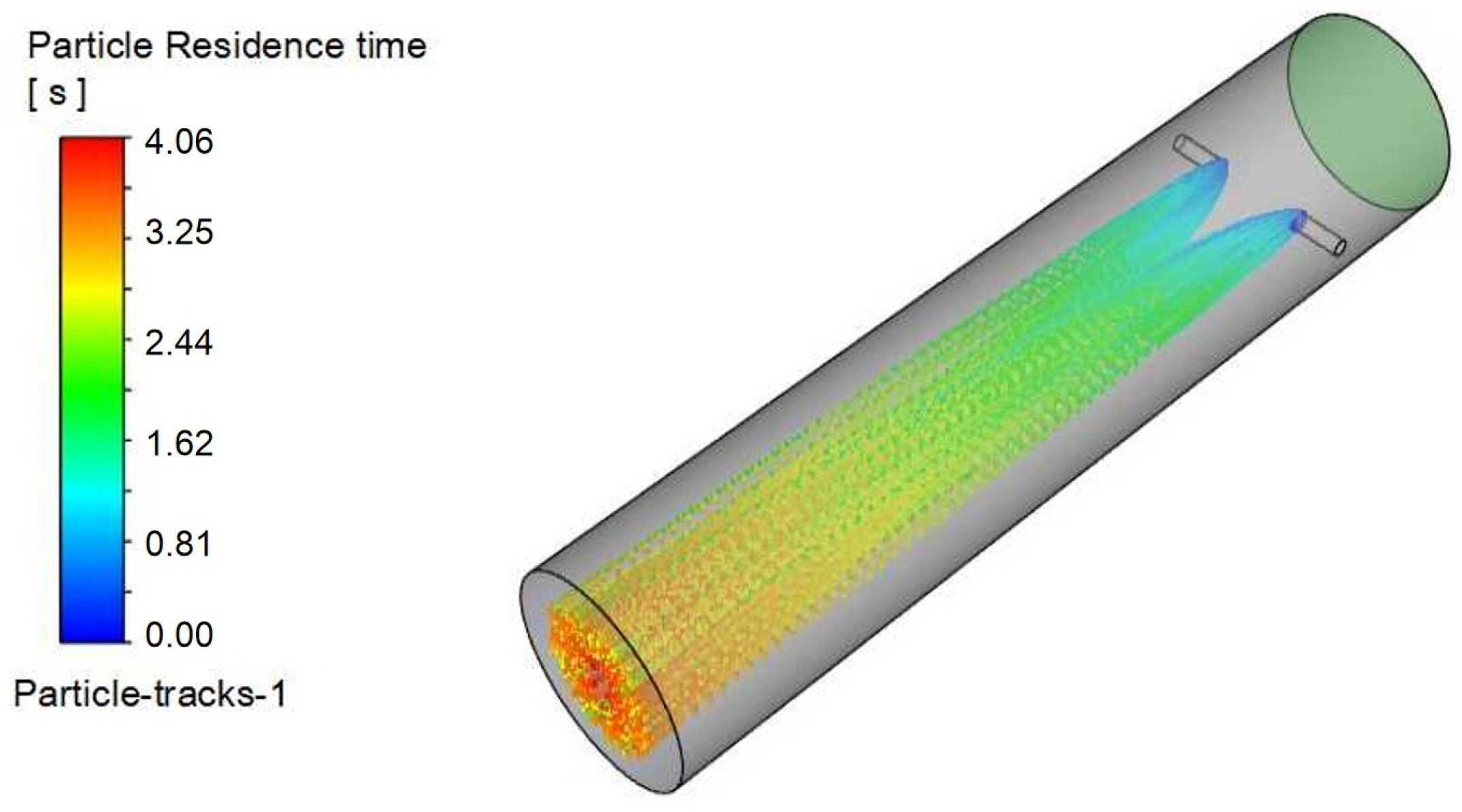

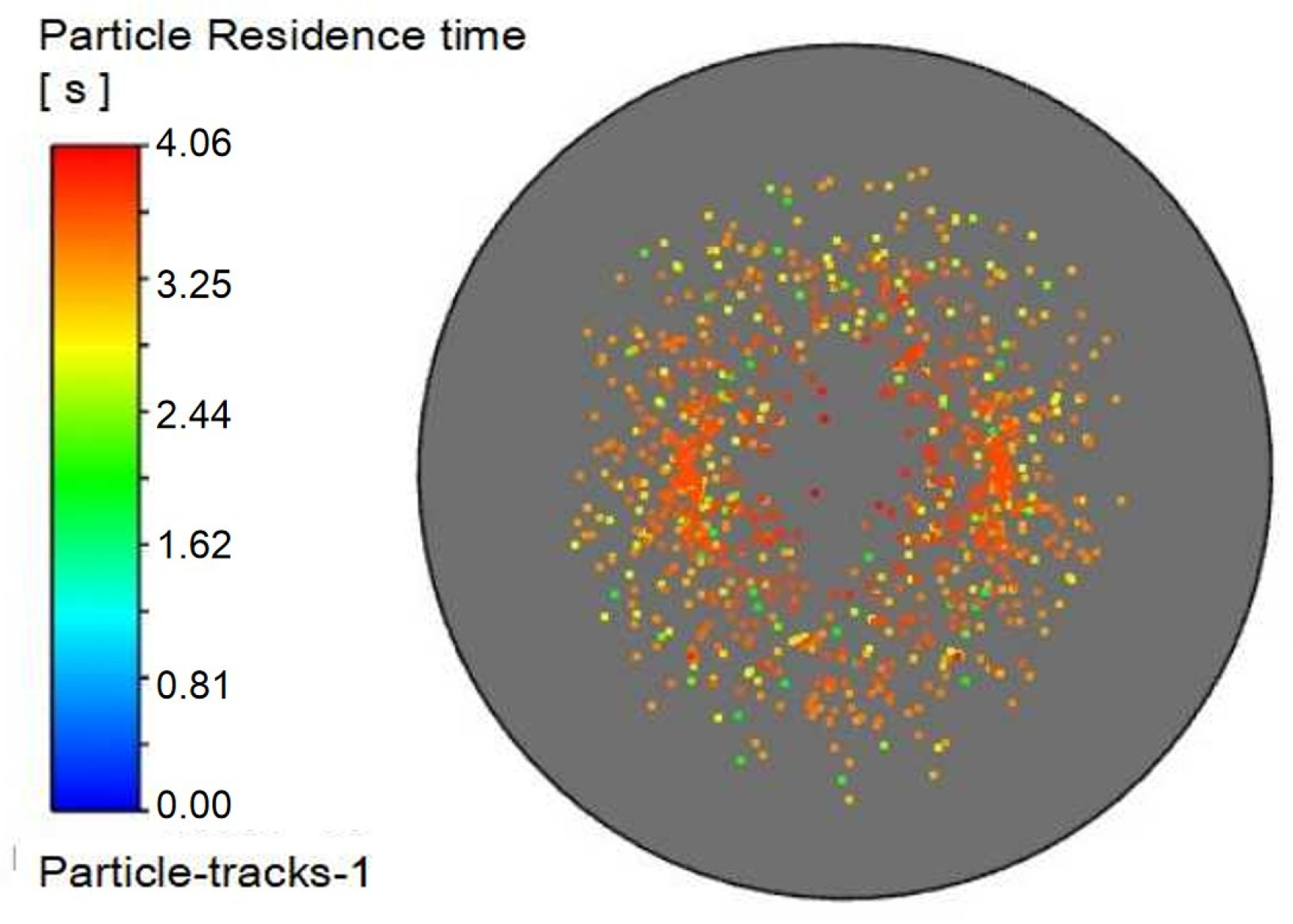

To evaluate the effect of injection orientation on process performance, simulations were conducted with a fixed natural gas velocity while varying the injection angle relative to the main pipeline. The injection pipe was oriented at 45°, 60°, 75°, and 90° to the main pipe axis, representing 15° increments. The resulting flow characteristics are presented in the following figures:

Figure 15 shows velocity contours on the X-Z plane within the injection pipe,

Figure 16 illustrates triazine droplet trajectories, and

Figure 17 displays the corresponding outlet droplet distributions.

Turbulence is a highly complex three-dimensional, unsteady, and rotational irregular flow that enables intense mixing and diffusion of fluid microclusters in space. When droplets are injected into the pipeline at a certain angle, they disturb the fluid in the pipeline and generate turbulent vortices. These vortices can accelerate the mixing process between the desulfurizing agent and the surrounding gas, improving mixing efficiency.

When a jet flows in a pipeline, it gradually diffuses to the surroundings due to the pressure difference and mixing effect with the surrounding static fluid. The smaller the angle between the nozzle and the pipeline axis, the greater the velocity of the jet’s central axis, and the correspondingly smaller the diffusion range; while a larger angle may reduce the jet’s propulsive force, it expands the diffusion range, which helps to uniformly distribute droplets in the pipeline.

It can be observed in

Table 6 that as the injection angle decreases, the Sauter mean diameter of outlet droplets decreases gradually, indicating that droplet dispersion improves with decreasing injection angle. The injection angle of 45° achieves better droplet dispersion (smaller D

32) and larger gas–liquid interfacial area, which provides favorable precursor conditions for the mass transfer-reaction process.