Multi-Objective Optimization of Sucker Rod Pump Operating Parameters for Efficiency and Pump Life Improvement Based on Random Forest and CMA-ES

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Physics and Simulation-Based Approaches

2.2. Data-Driven Prediction and Intelligent Optimization

3. Mathematical Model of Lifting System Design

3.1. Optimization Variables

3.2. Objective Function

3.3. Constraints

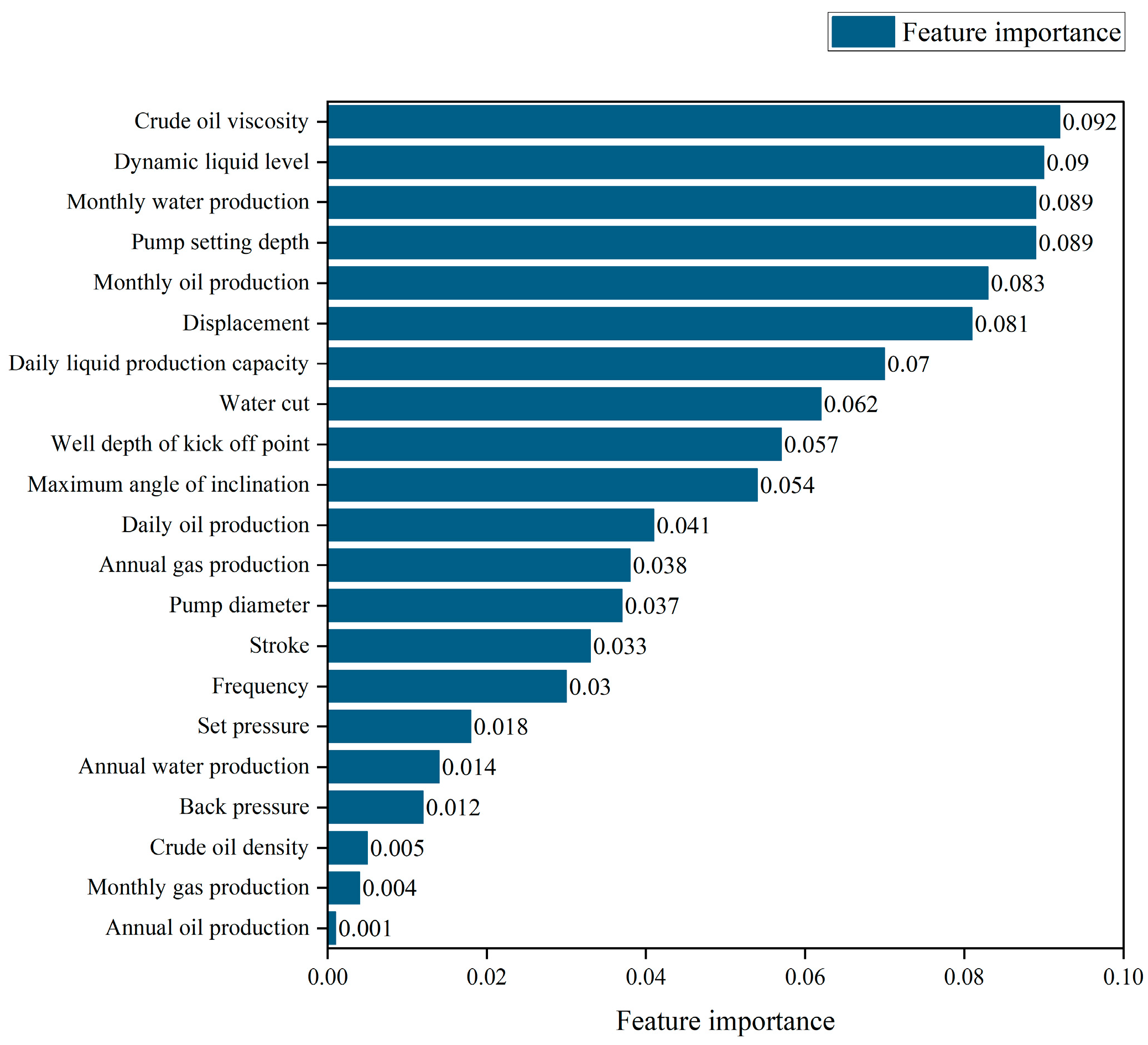

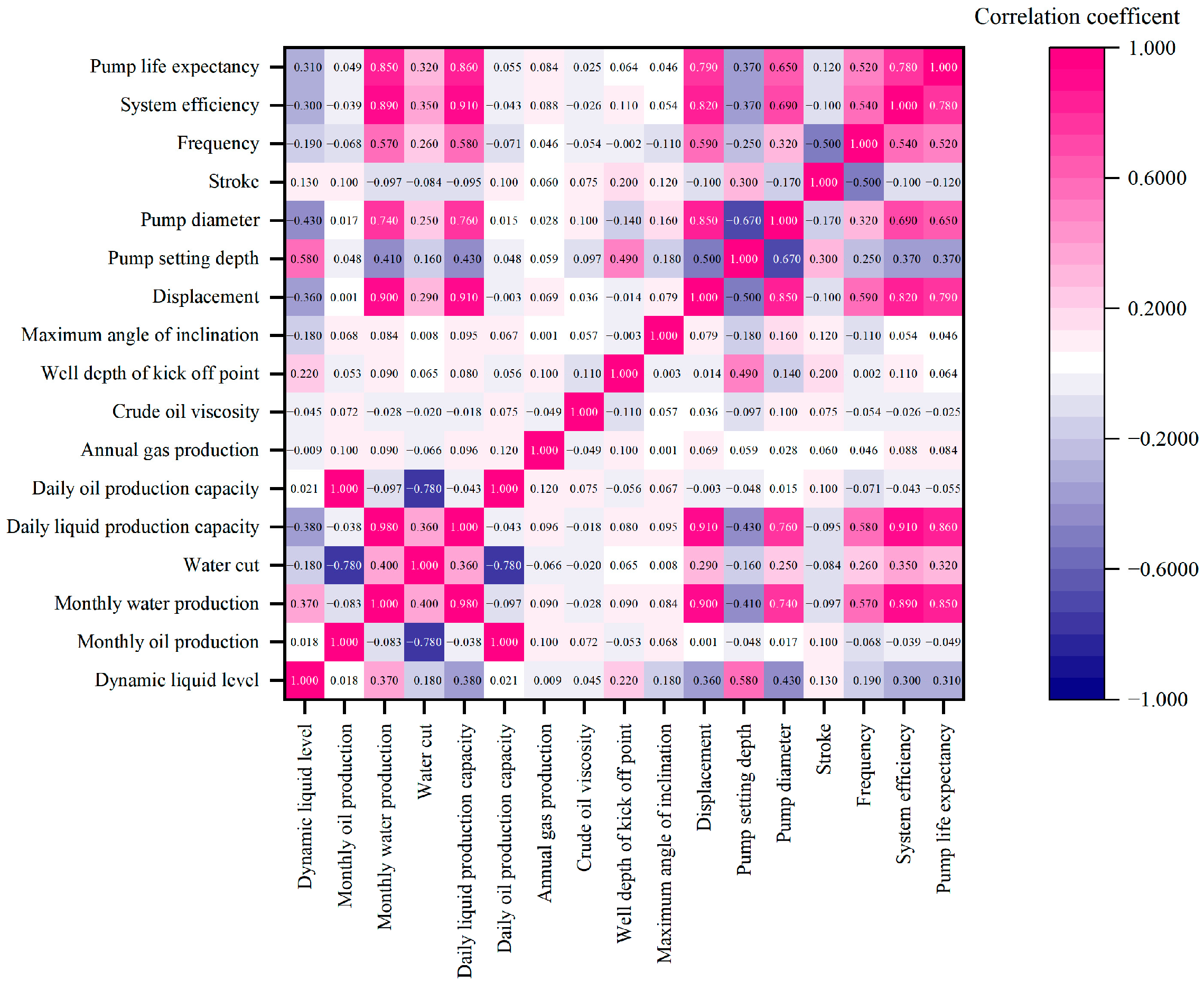

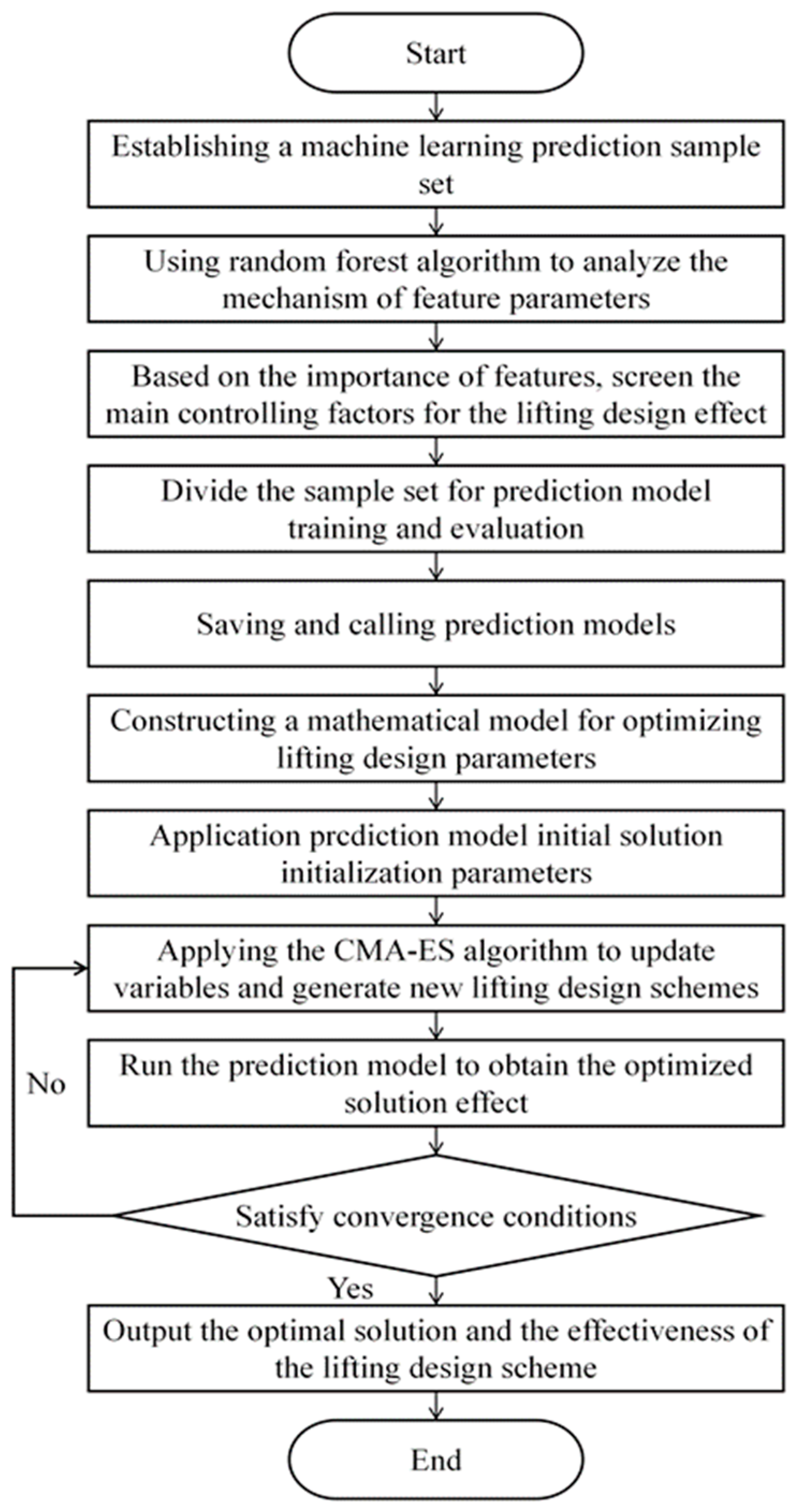

4. Lifting System Performance Prediction Model

4.1. Establishment of the Sample Library

4.2. Model Architecture

4.3. Training Method and Performance Evaluation

5. Design of the Intelligent Optimization Algorithm

5.1. CMA-ES Algorithm

5.2. Target Conversion

5.3. Transform Discrete Data into Continuous

5.4. Processing Strategy for Nonlinear Constraints

6. Example Application and Analysis

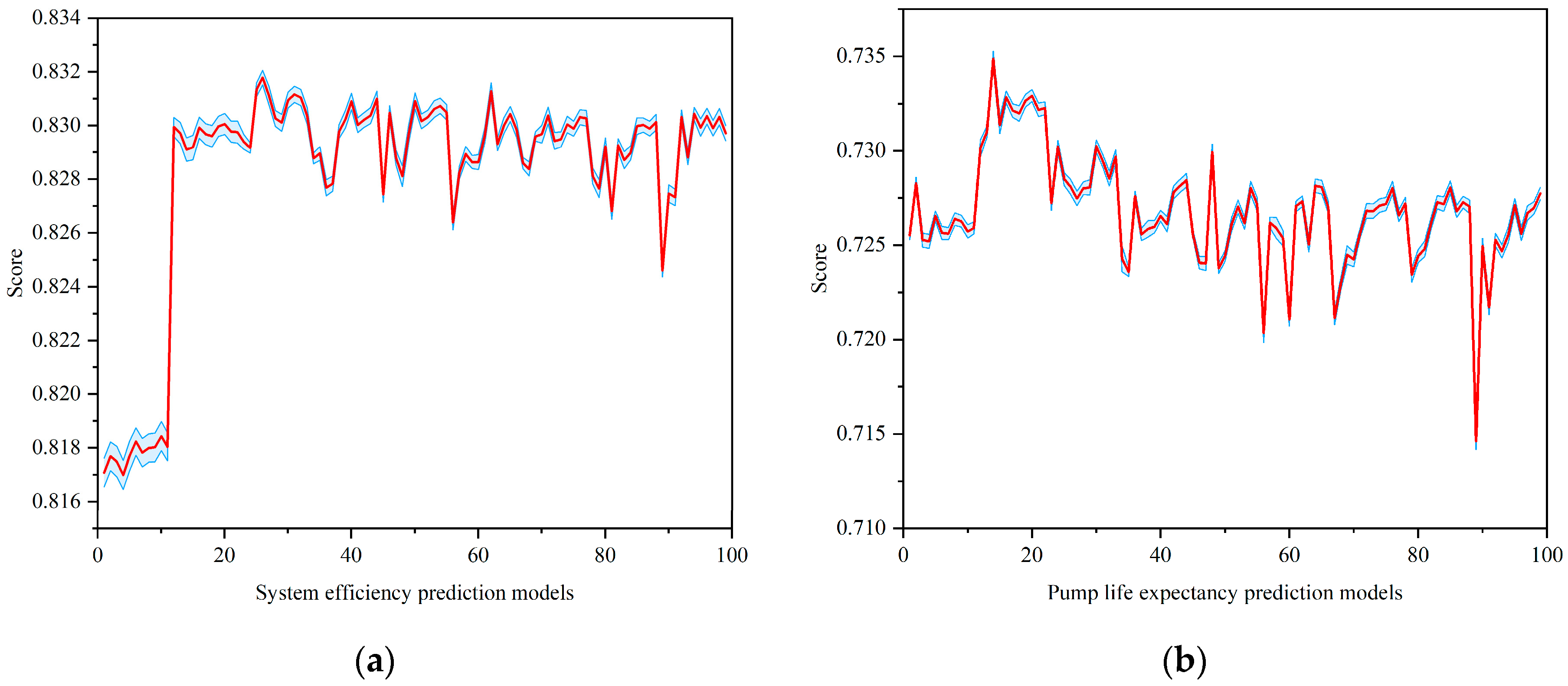

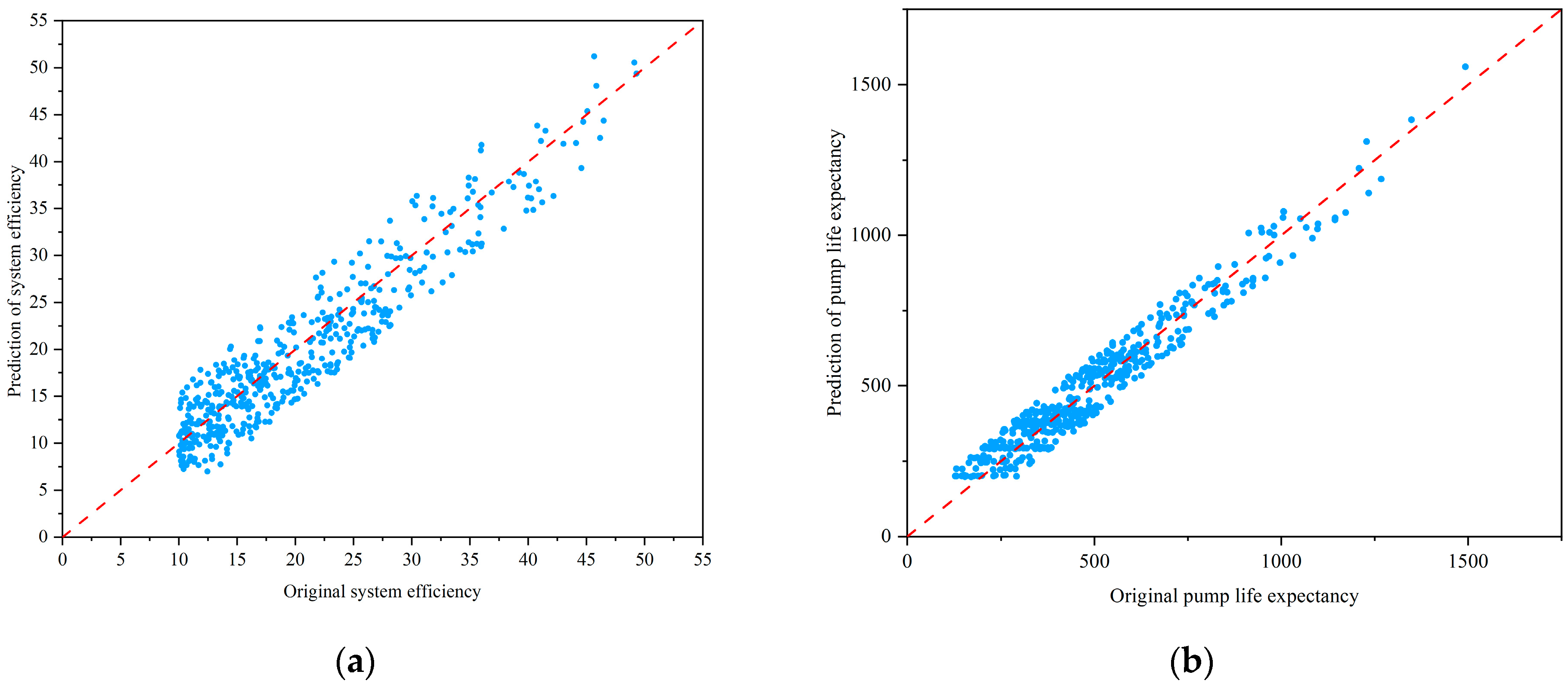

6.1. Performance Evaluation of the Lifting System Effect Prediction Model

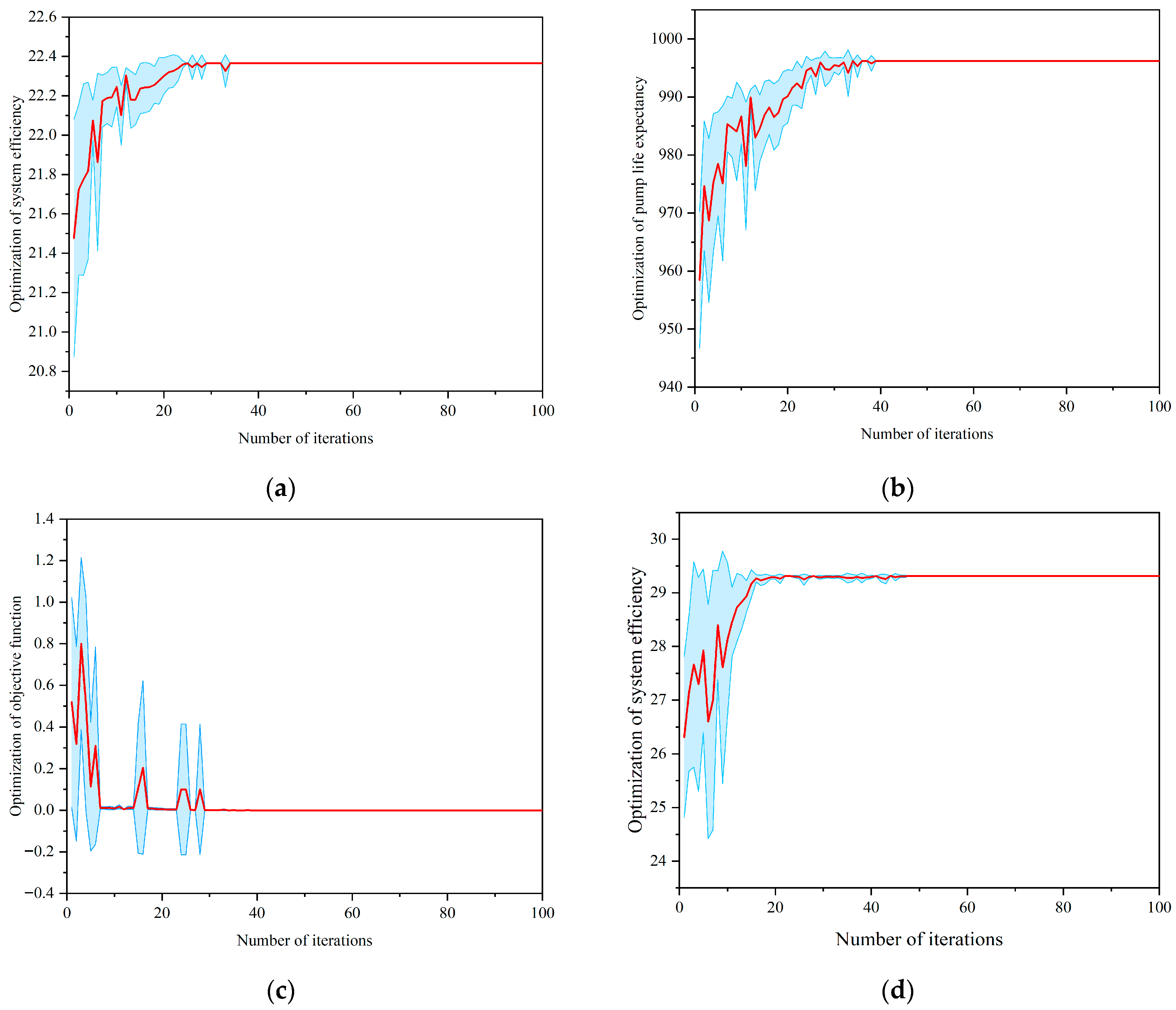

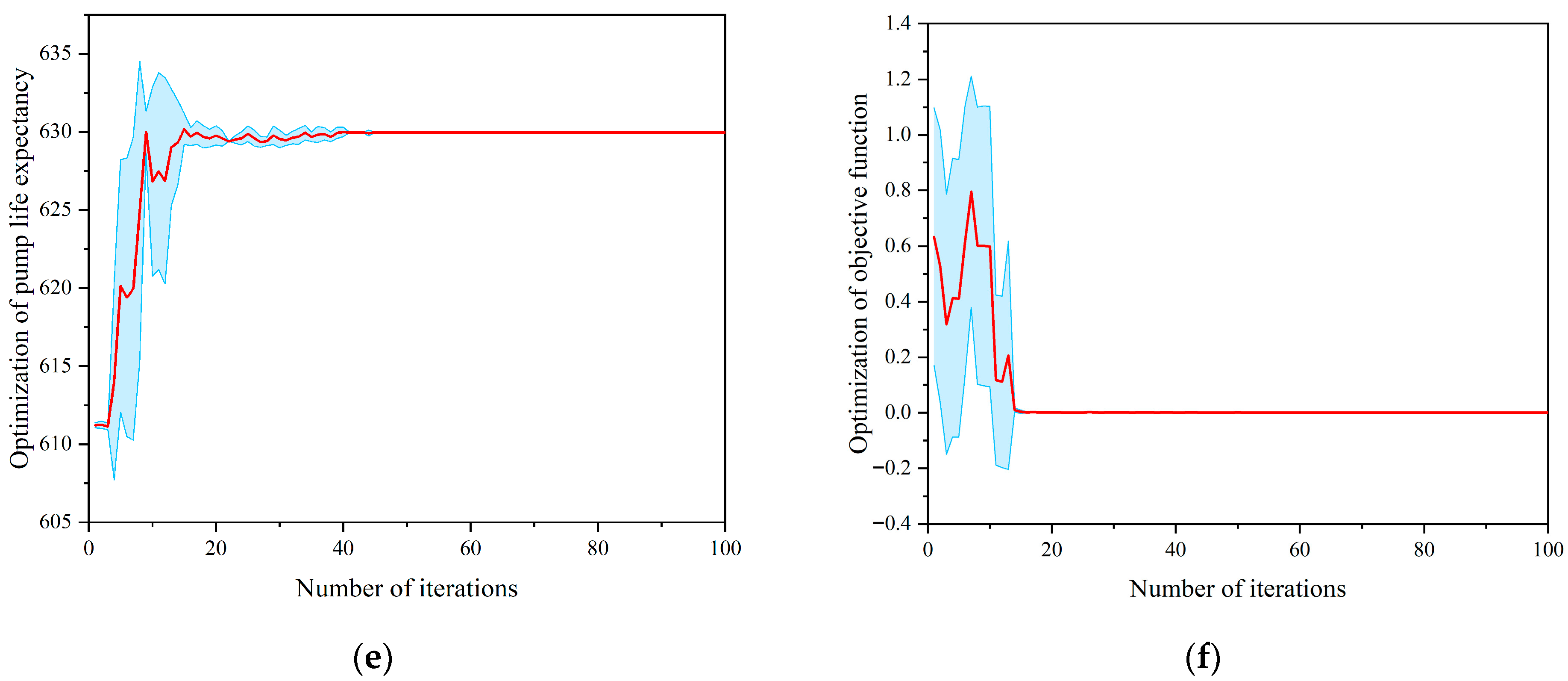

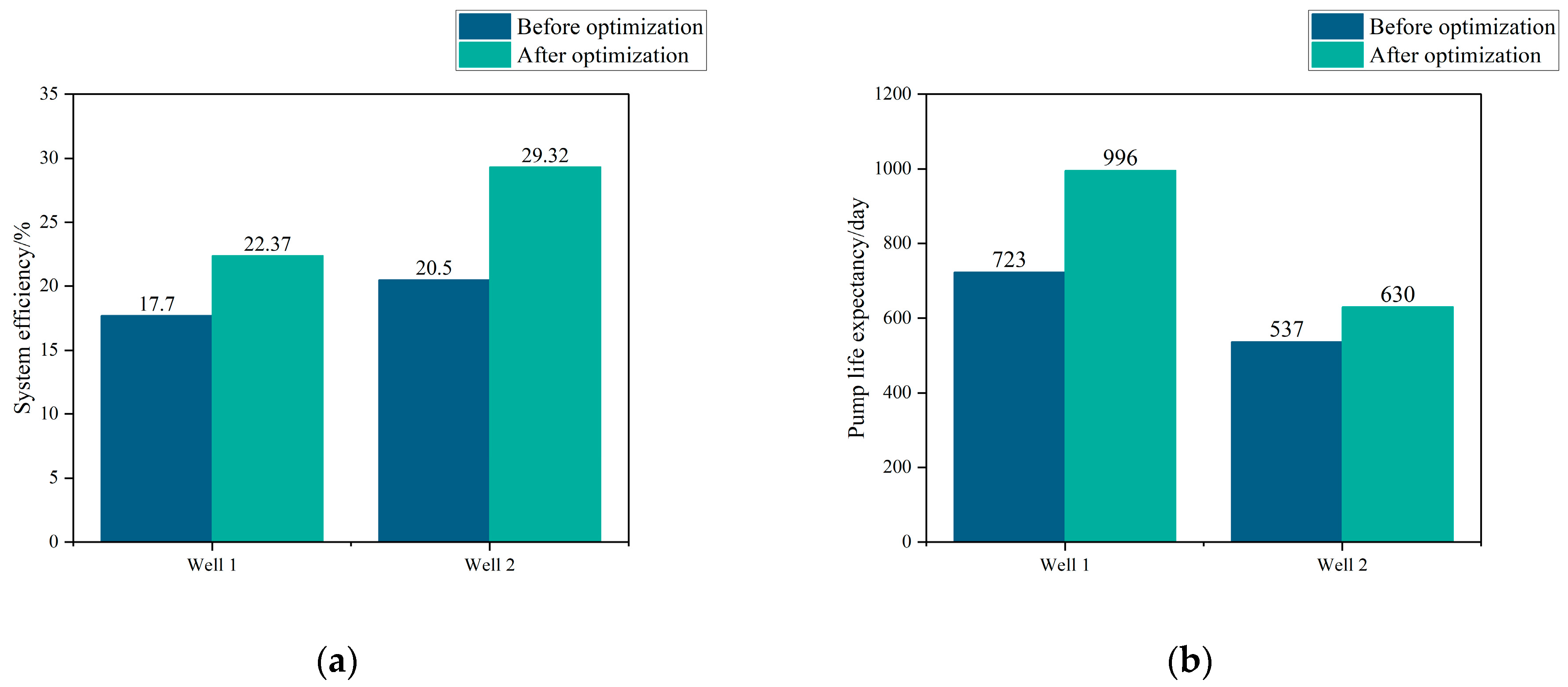

6.2. Optimization Performance Evaluation of Lifting System Design Parameters

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Greg, S. Technology Focus: Artificial Lift (March 2022). J. Pet. Technol. 2022, 74, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Jian, J.; Pavesi, G.; Yuan, S.; Wang, W. Application of intelligent methods in energy efficiency enhancement of pump system: A review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 11592–11606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khormali, A.; Sharifov, A.R.; Torba, D.I. The control of asphaltene precipitation in oil wells. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2018, 36, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of Crosslinking Agents and Reservoir Conditions on the Propagation of Fractures in Coal Reservoirs During Hydraulic Fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ansari, U. From CO2 Sequestration to Hydrogen Storage: Further Utilization of Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansena, B.; Tolbertb, B.; Vernona, C.; Hedengrena, J.D. Model predictive automatic control of sucker rod pump system with simulation case study. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2019, 121, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, C.; Xue, K.; Zhang, Z. Simulation analysis of nonlinear friction of rod string in sucker rod pumping system. J. Comput. 2019, 14, 091008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S. An equivalent vibration model for optimization design of carbon/glass hybrid fiber sucker rod pumping system. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 207, 109148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D. Study on the Combination of Pump Rod Pipe in Complex Structure. Sci. Program. 2022, 2022, 3041911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbauer, C.; Langbauer, T.; Fruhwirth, R.; Mastobaev, B. Sucker rod pump frequency-elastic drive mode development–from the numerical model to the field test. Liq. Gaseous Energy Resour. 2021, 1, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalikop, S.V.; Albishini, R.; Freudenberger, M.; Scheichl, B.; Langbauer, C.; Eder, S.J. An Extended Computational Fluid Dynamics Model and Its Experimental Validation to Improve Sucker Rod Pump Operation and Design. SPE J. 2025, 30, 6249–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Liao, Z.; Hu, S.; Yi, J.; Li, T. Decision Parameter Optimization of Beam Pumping Unit Based on BP Networks Model. In Fuzzy Information & Engineering and Operations Research & Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Zhang, H.; Ling, K. The optimization approach of casing gas assisted rod pumping system. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 2016, 32, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhang, N.; Sun, D. Artificial lift methods optimising and selecting based on big data analysis technology. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference 2019, Beijing, China, 26–28 March 2019; p. D011S0R03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Qi, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, H. Neural Network-Based Beam Pumper Model Optimization. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 8562387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, X.; Wang, X.; Xie, Y.; Xing, G.; Chen, L. Association rules mining for long uptime sucker rod pumping units. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 245, 110026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Shi, J.; Su, L.; Shan, H.; Sun, C.; Miao, G.; Wang, Y.; Shi, L.; et al. Production optimizaton and application of combined artificial-lift systems in deep oil wells. In Proceedings of the SPE Middle East Artificial Lift Conference and Exhibition 2016, Manama, Kingdom of Bahrain, 30 November–1 December 2016; p. D021S07R03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almedallah, M.K.; Clark, S.; Walsh, S.D.C. Schedule Optimization To Accelerate Offshore Oil Projects While Maximizing Net Present Value in the Presence of Simultaneous Operations, Weather Delays, and Resource Limitations. SPE Prod. Oper. 2022, 37, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcántara, A.; Ruiz, C. On data-driven chance constraint learning for mixed-integer optimization problems. Appl. Math. Model. 2023, 121, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temizel, C.; Canbaz, C.H.; Betancourt, D.; Ozesen, A.; Acar, C.; Krishna, S.; Saputelli, L. A comprehensive review and optimization of artificial lift methods in unconventionals. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition 2020, Virtual, 5–7 October 2020; p. D041S53R08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.; Tran, S. Hybrid Electrical-Submersible-Pump/Gas-Lift Application to Improve Heavy Oil Production: From System Design to Field Optimization. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2022, 144, 083006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, G. Ways to obtain optimum power efficiency of artificial lift installations. In Proceedings of the SPE Oil and Gas India Conference and Exhibition 2010, Mumbai, India, 20–22 January 2010; p. SPE-126544-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, H.; Merey, S. Design of Electrical Submersible Pump system in geothermal wells: A case study from West Anatolia, Turkey. Energy 2021, 230, 120891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Z. Intelligent identification for working-cycle stages of excavator based on main pump pressure. Autom. Constr. 2020, 109, 102991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk Prediction of Gas Hydrate Formation in the Wellbore and Subsea Gathering System of Deep-Water Turbidite Reservoirs: Case Analysis from the South China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Schumann, H.; Jin, G. Application of Data Mining to Small Data Sets: Identification of Key Production Drivers in Heterogeneous Unconventional Resources. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 2023, 26, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chris, C. Machine-Learning Approach Optimizes Well Spacing. J. Pet. Technol. 2021, 73, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, V.; Maniar, H.; Abubakar, A.; Zhao, T. Comparative study of machine-learning-based methods for log prediction. Petrophysics 2023, 64, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.H. Biostatistics 104: Correlational analysis. Singap. Med. J. 2003, 44, 614–619. [Google Scholar]

- Chris, C. Machine-Learning Model Improves Gas Lift Performance and Well Integrity. J. Pet. Technol. 2022, 74, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Afshin, T.; Mahsheed, R.; Madiyar, K.; Ingkar, A. Artificial neural network, support vector machine, decision tree, random forest, and committee machine intelligent system help to improve performance prediction of low salinity water injection in carbonate oil reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 219, 111046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Yin, X.; Yao, X.; Cheng, Z.; Yan, B.; Chen, G. Prediction of NH3 and HCN yield from biomass fast pyrolysis: Machine learning modeling and evaluation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 885, 163743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olumegbon, I.A.; Alade, I.O.; Oyedeji, M.O.; Qahtan, T.F.; Bagudu, A. Development of machine learning models for the prediction of binary diffusion coefficients of gases. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, B.; Kumar, A.; Mallipeddi, R.; Lee, D.-G. CMA-ES with exponential based multiplicative covariance matrix adaptation for global optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 79, 101296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.; Mohammad, S. (μ + λ) Evolution strategy algorithm in well placement, trajectory, control and joint optimisation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 177, 1042–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng-Hooi, T.; Junita, M.-S. MO-NFSA for solving unconstrained multi-objective optimization problems. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 2527–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmelash Mollalign, M.; Berhanu Guta, W.; Allen, R. Solving multi-objective linear fractional decentralized bi-level decision-making problems through compensatory intuitionistic fuzzy mathematical method. J. Comput. Sci. 2023, 71, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, L.; Shiue, M. Finite time synchronization of the continuous/discrete data assimilation algorithms for Lorenz 63 system based on the back and forth nudging techniques. Results Appl. Math. 2023, 20, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, T.D.; Haynes, R.D. Joint optimization of well placement and control for nonconventional well types. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 126, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.d.A.; Minnett, P.J.; Ebecken, N.F.F.; Landau, L. Machine-Learning Classification of SAR Remotely-Sensed Sea-Surface Petroleum Signatures—Part 1: Training and Testing Cross Validation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massimo, C.; Luigi, B.; Gino, C.; Giovanni, G. Exploring performance and robustness of shallow landslide susceptibility modeling at regional scale using different training and testing sets. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Alarood, A.A.S.; Uddin, M.I.; Rehman, I.U. Utilizing grid search cross-validation with adaptive boosting for augmenting performance of machine learning models. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeti, S.; Balasubramanian, S.; Ramasamy, D.; Mohammed, Y. COVID-19 cases prediction using SARIMAX Model by tuning hyperparameter through grid search cross-validation approach. Expert. Syst. 2023, 40, e13086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Evaluating Indicator | System Efficiency | Pump Life Expectancy |

|---|---|---|

| Training set R2 | 0.93 | 0.80 |

| Validation set R2 | 0.83 | 0.73 |

| Test set R2 | 0.80 | 0.71 |

| Manufacturing Parameter | Well 1 | Well 2 | Manufacturing Parameter | Well 1 | Well 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic liquid level/m | 1002 | 987 | Well depth of kick off point/m | 584.76 | 747.27 |

| Crude oil viscosity/MPa·s | 1147 | 1264 | Stroke/m | 4.78 | 6.05 |

| Water cut/% | 81.2 | 70.4 | Pump setting depth/m | 1032.13 | 1094.84 |

| Annual gas production/109 m3 | 0.7 | 0.21 | Pump diameter/mm | 70 | 57 |

| Daily fluid production capacity/t | 5.7 | 2.4 | Frequency/times·min−1 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Maximum angle of inclination/° | 42.6 | 28.5 | System efficiency/% | 17.7 | 20.5 |

| Monthly oil production/107 t | 32 | 72 | Pump life expectancy/day | 723 | 537 |

| Daily oil production capacity/t | 4.8 | 1.6 |

| Optimize the Well | Stroke/m | Pump Setting Depth/m | Pump Diameter/mm | Frequency/times·min−1 | System Efficiency/% | Pump Life Expectancy/d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well 1 | 5.71 | 1218.58 | 83 | 0.82 | 22.37 | 996 |

| Well 2 | 4.99 | 1250.26 | 57 | 1.54 | 29.32 | 630 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Chen, L.; Yu, W.; Li, M.; Wu, Y. Multi-Objective Optimization of Sucker Rod Pump Operating Parameters for Efficiency and Pump Life Improvement Based on Random Forest and CMA-ES. Processes 2025, 13, 3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123871

Wang X, Zhuang Y, Xie Y, Chen L, Yu W, Li M, Wu Y. Multi-Objective Optimization of Sucker Rod Pump Operating Parameters for Efficiency and Pump Life Improvement Based on Random Forest and CMA-ES. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123871

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiang, Yuhao Zhuang, Yixin Xie, Lin Chen, Wenjie Yu, Ming Li, and Ying Wu. 2025. "Multi-Objective Optimization of Sucker Rod Pump Operating Parameters for Efficiency and Pump Life Improvement Based on Random Forest and CMA-ES" Processes 13, no. 12: 3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123871

APA StyleWang, X., Zhuang, Y., Xie, Y., Chen, L., Yu, W., Li, M., & Wu, Y. (2025). Multi-Objective Optimization of Sucker Rod Pump Operating Parameters for Efficiency and Pump Life Improvement Based on Random Forest and CMA-ES. Processes, 13(12), 3871. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123871