Operational Flexibility Assessment of Distributed Reserve Resources Considering Meteorological Uncertainty: Based on an End-to-End Integrated Learning Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Impact of Meteorological Uncertainty on the Operational Characteristics of Reserve Resources

1.2.2. Operational Flexibility Evaluation of Multi-Source Distributed Reserve Resources

1.2.3. Research Gap

1.3. Contributions

- (1)

- A distributed reserve capacity response evaluation system for meteorological uncertainty is constructed. This study quantifies the reserve potentials of various resources under different meteorological conditions through optimization modelling and Minkowski aggregation and uniformly portrays the reserve boundaries of distributed resource clusters under different spatial and temporal conditions, so as to provide high-quality samples for the subsequent machine learning modelling.

- (2)

- A high-dimensional meteorological feature selection method considering correlation and causality is proposed. In this study, minimum redundancy–maximum relevance principle and Granger causality test are combined to construct a subset of features with interpretability and stability between the multidimensional NWP data and the spare capacity, which can enhance the credibility of the data-driven model.

- (3)

- The integrated weather-reserve learning model is constructed considering the diversity of models. Based on the stacking framework, this study proposes an adaptive selection strategy for base and meta learners that takes into account model diversity and combination performance, which improves the prediction accuracy and generalization ability of the model under high-dimensional, nonlinear weather perturbation conditions for distributed resource reserve potential.

2. Methodology

2.1. Characterization of Reserve Resource Capacity with Meteorological Uncertainty

2.1.1. Operational Modelling of Distributed Power Generations

2.1.2. Operational Modelling of Flexible Loads

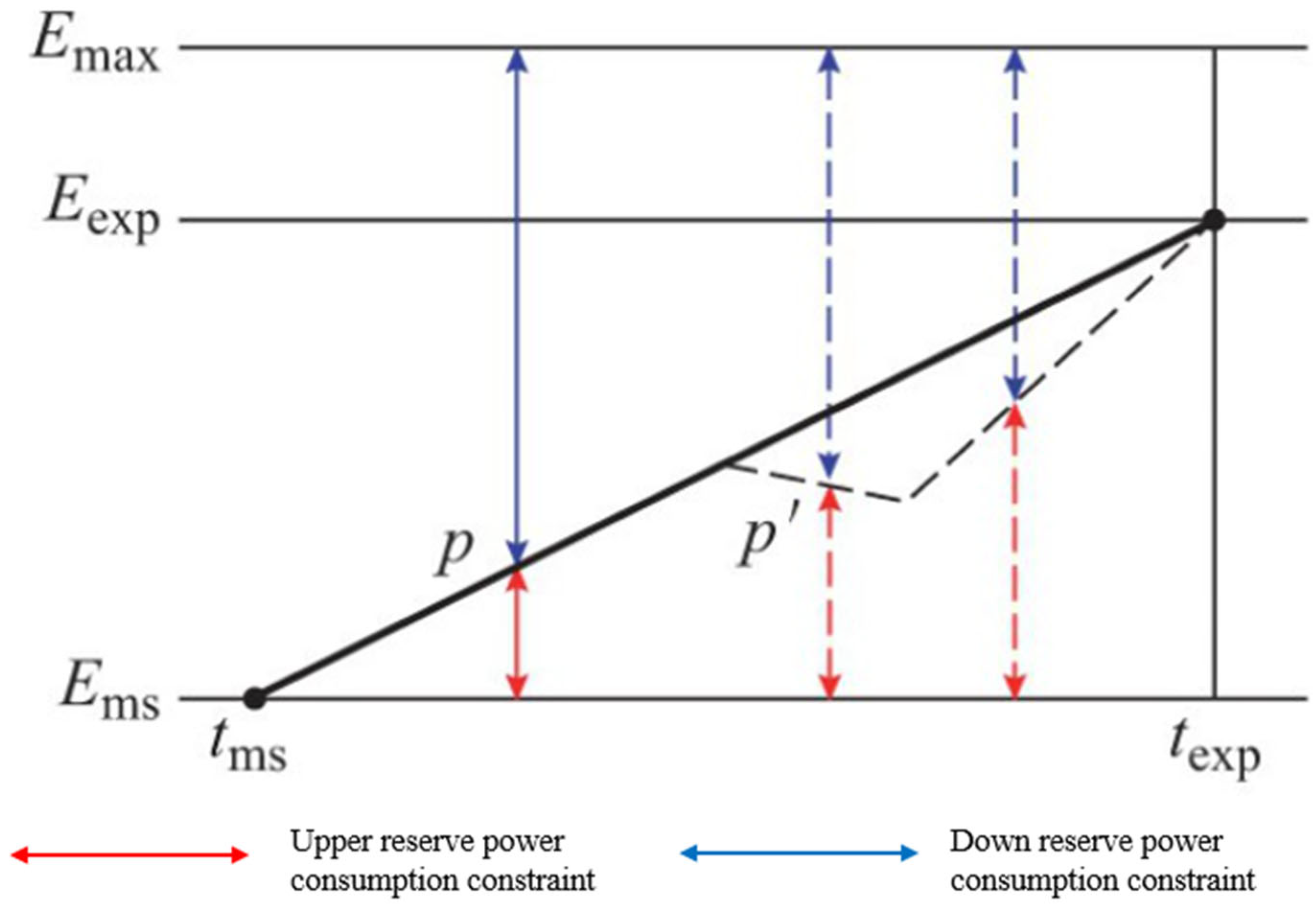

2.1.3. Operational Modelling of Distributed Energy Storage

2.2. MRMR Algorithm Considering Causality

2.3. Adaptive Integrated Learning Framework Considering Model Diversity

3. Case Study

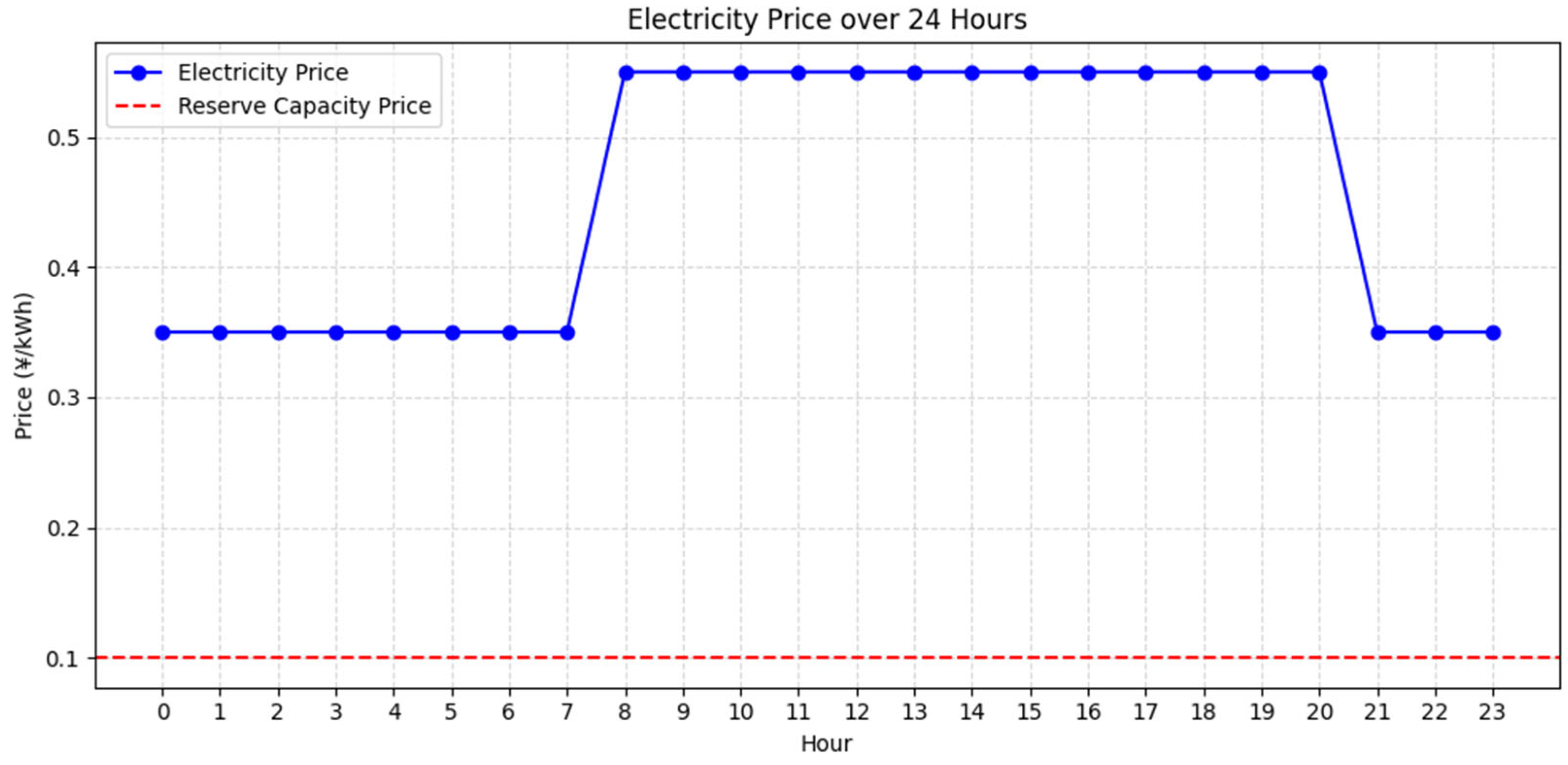

3.1. Experiment Details and Settings

3.2. Spare Capacity Generation and Feature Selection

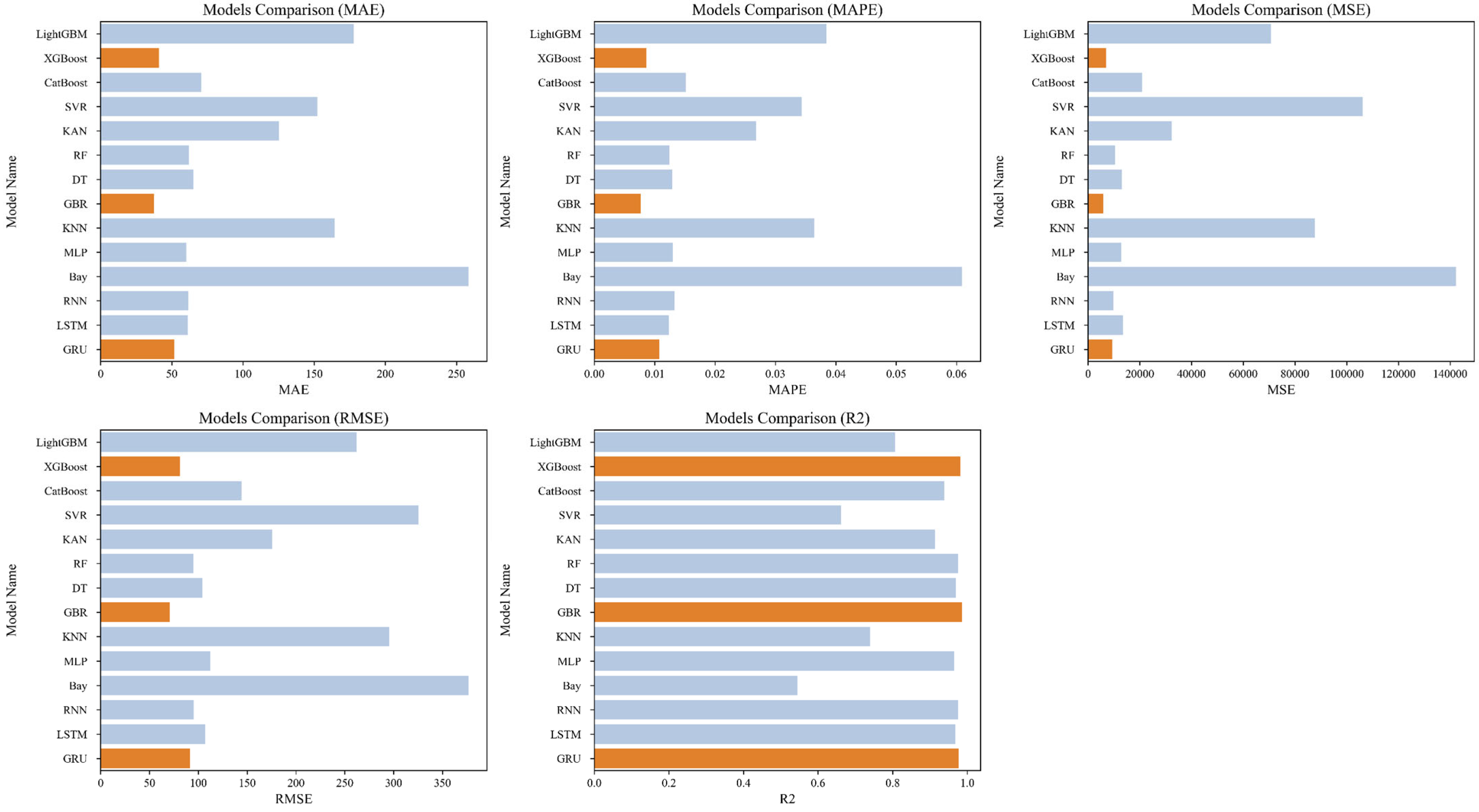

3.3. Model Parameter Setting and Difference Analysis

3.4. Prediction Result Analysis

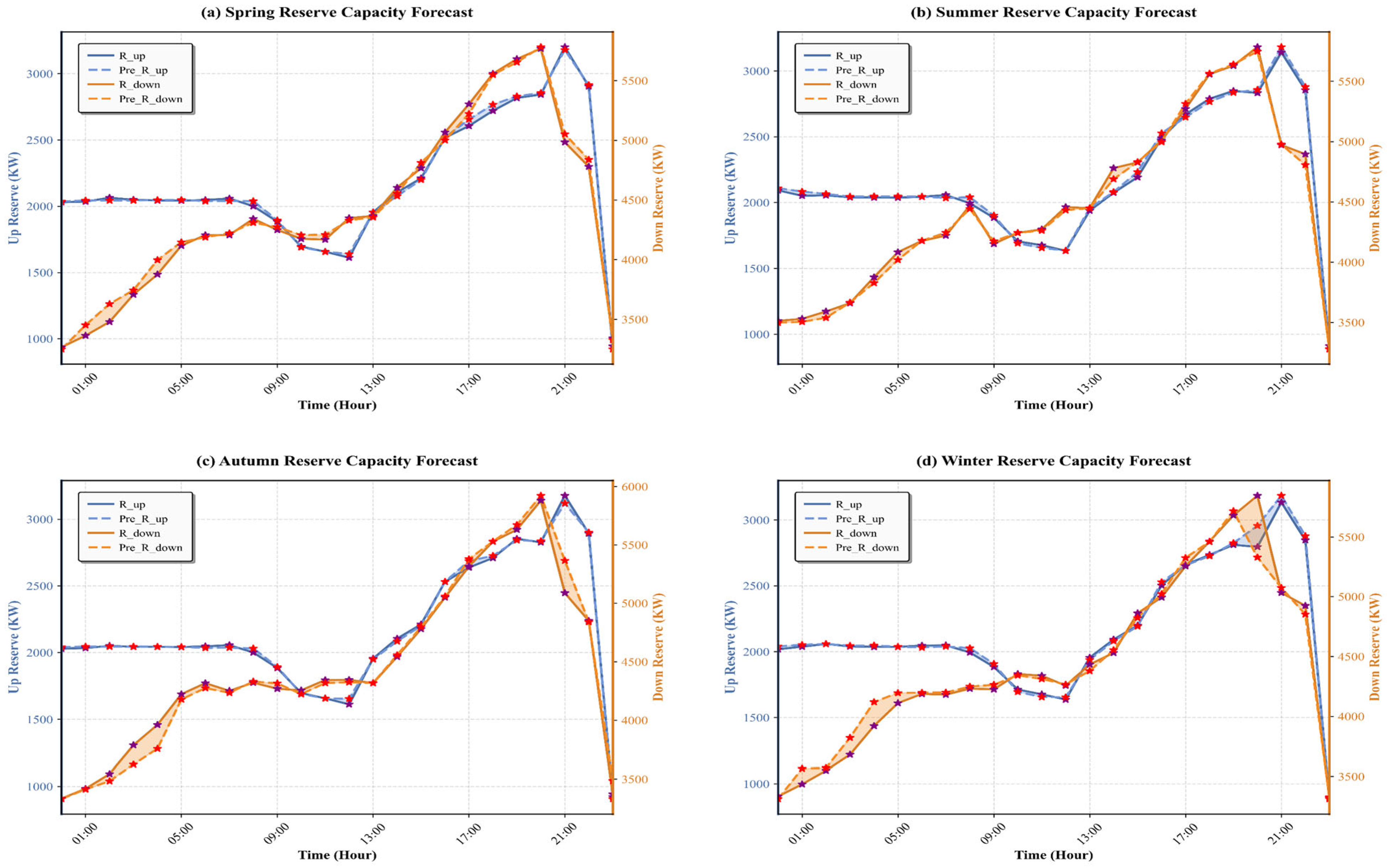

3.4.1. Reserve Capacity of Typical Scenes in Four Seasons

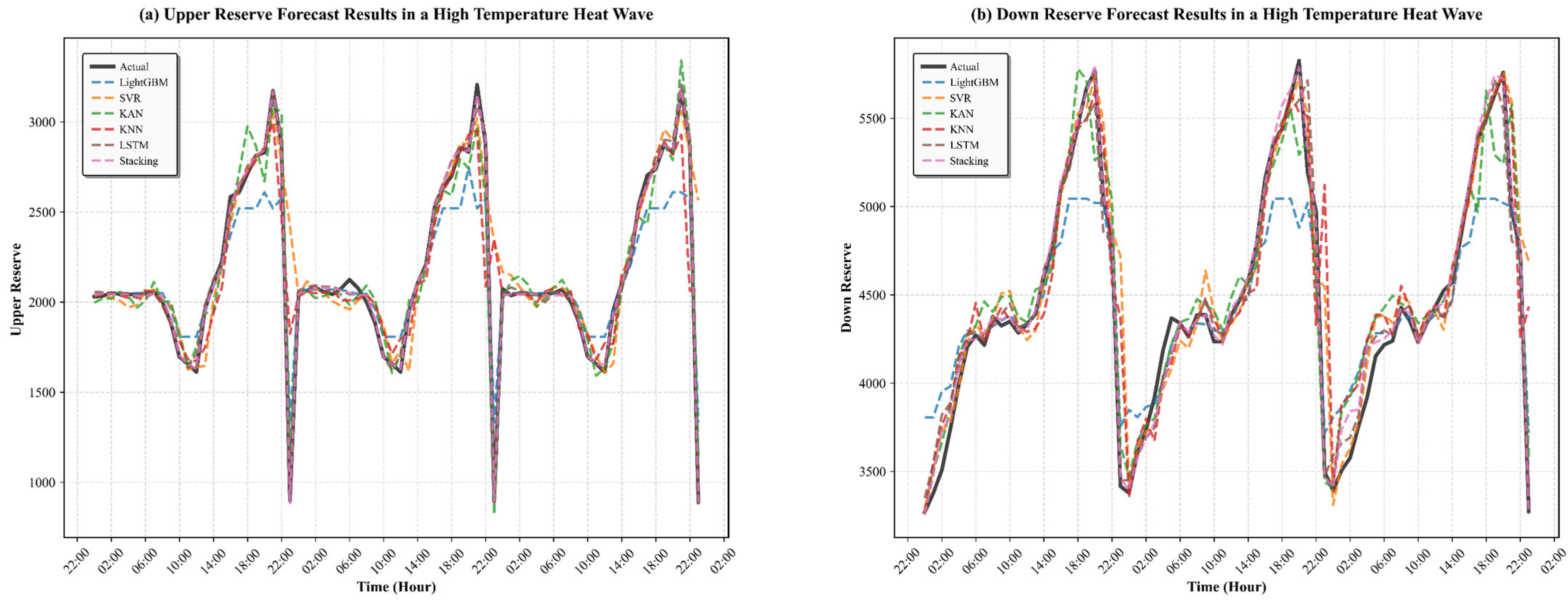

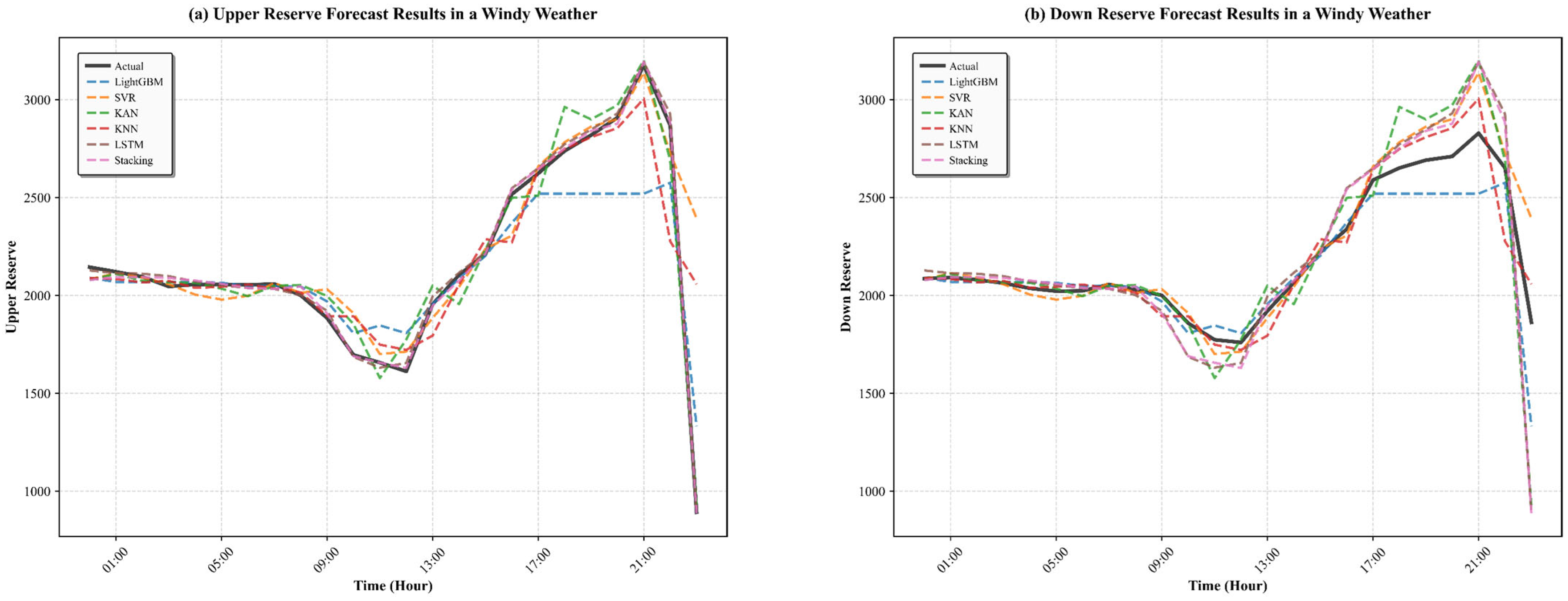

3.4.2. Prediction Performance of the Model Under Extreme Climate

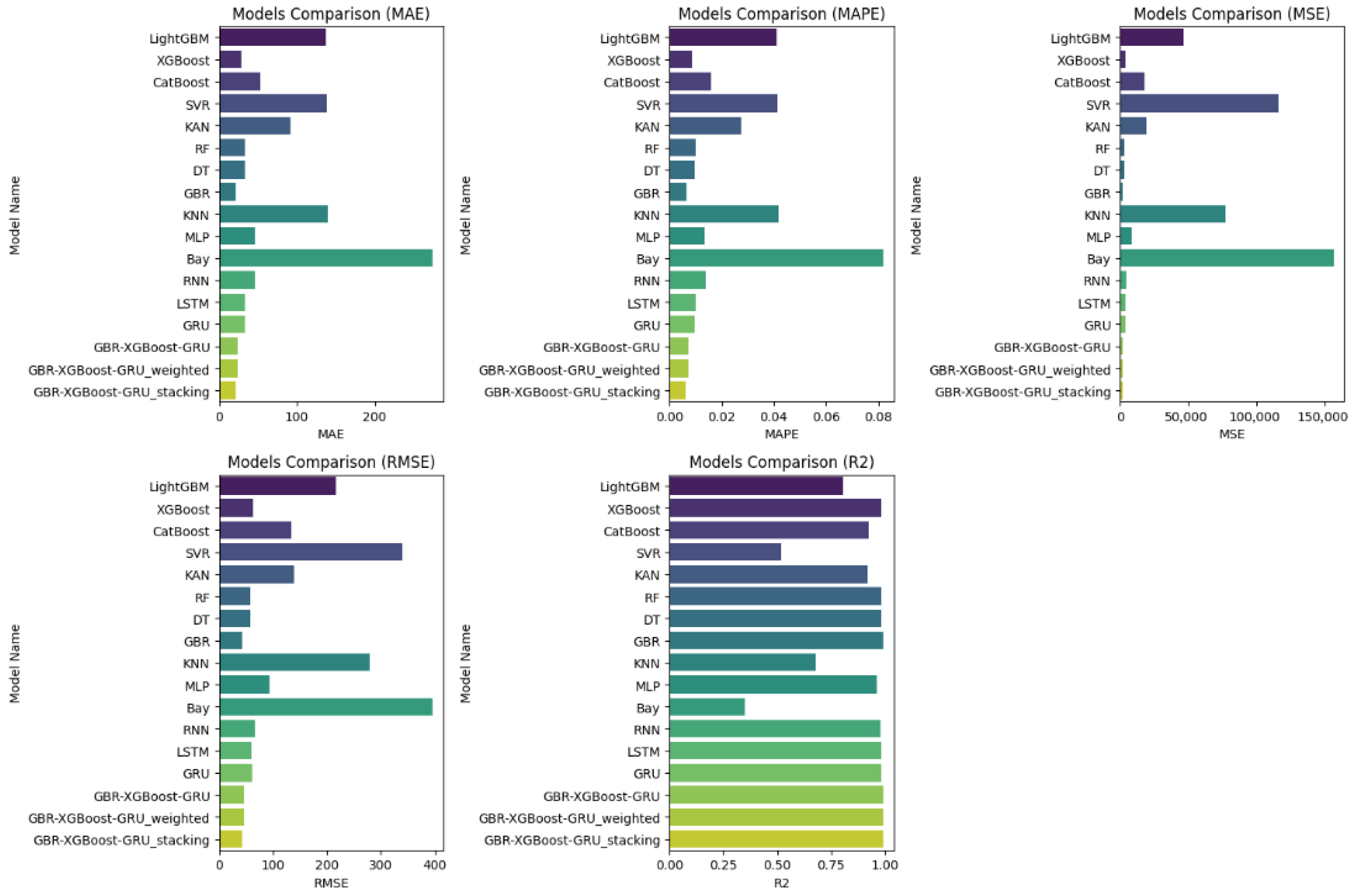

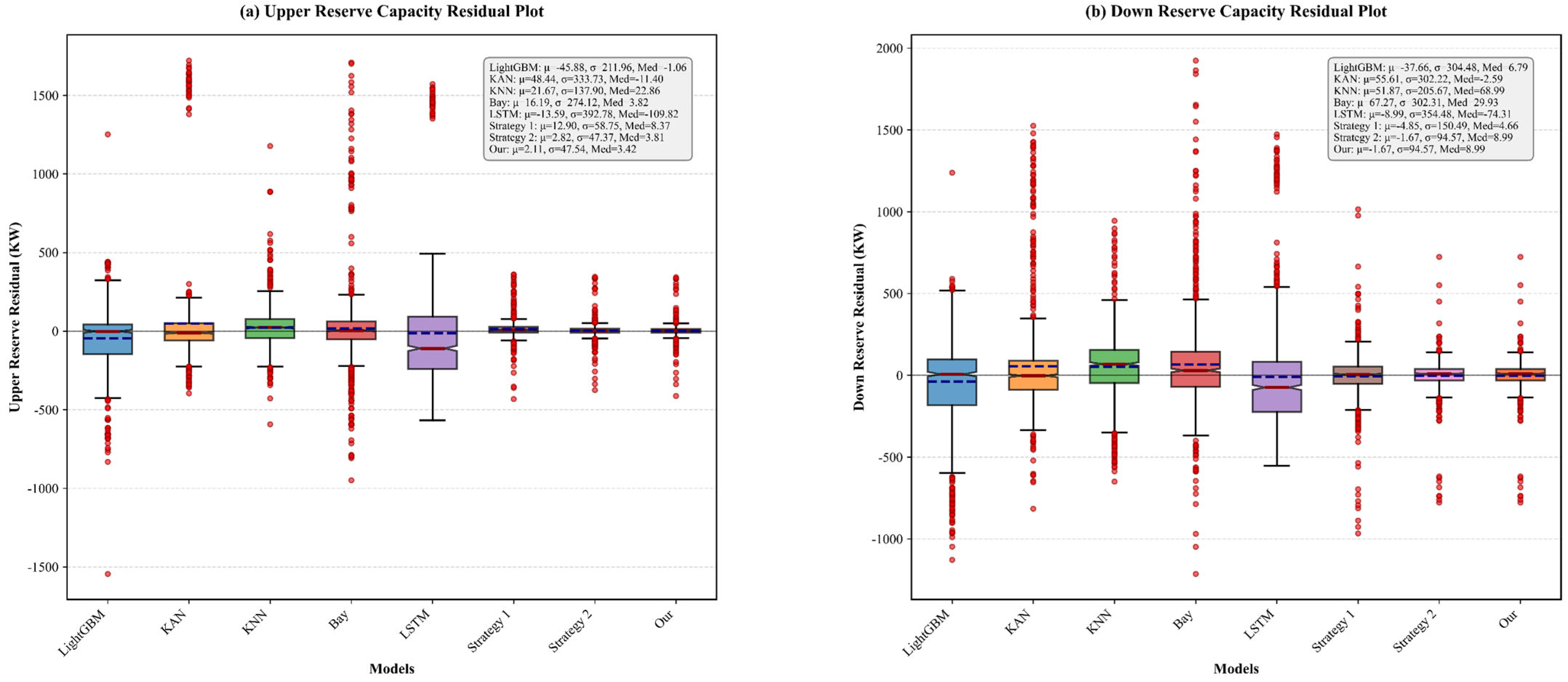

3.4.3. Compared with Single Model and Benchmark Strategy

3.4.4. Compared with Other Mixed Models

4. Conclusions and Future Works

4.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Temporal characteristics and feature interpretability enable efficient modelling. Distributed reserve capacity on the generation, load, and storage sides exhibits clear diurnal and weekly patterns, providing a stable foundation for predictive modelling. By combining mRMR with multi-stage Granger causality screening, the framework extracts key meteorological drivers and removes redundant variables, substantially enhancing training efficiency and preserving physical interpretability.

- (2)

- The stacking model achieves a superior balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Across upper- and lower-reserve prediction tasks, the proposed integrated model attains an average R2 of 0.994. Meanwhile, its training times (130.85 s and 133.71 s) are significantly lower than those of conventional neural or hybrid models, demonstrating clear advantages in generalization, scalability, and overall computational performance.

- (3)

- High robustness under extreme weather and clear superiority over other ensemble strategies. The model maintains stable error indices under extreme meteorological conditions such as heatwaves and strong-wind events, accurately capturing multi-peak reserve responses. Comparative experiments further show that the stacking strategy consistently outperforms simple averaging and MAE-weighted integration across all evaluation metrics, confirming its effectiveness as the optimal ensemble scheme.

4.2. Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| CatBoost | Categorical Boosting |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| KAN | Kolmogorov–Arnold Networks |

| RF | Random Forest |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| GBR | Gradient Boosting Regressor |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbours |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| Bay | Bayesian Ridge |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| Temp_center | Central temperature of membership function |

| Temp_std | Standard deviation of normal distribution in each temperature zone |

| Temp_weight | Influence weight of each temperature zone on access intention |

| Temperature | Actual ambient temperature |

| User-set comfort temperature | |

| Comfortable temperature tolerance intervals | |

| Heat conduction efficiency | |

| Refrigeration rate | |

| Electricity price-response threshold | |

| User indoor temperature | |

| Outdoor temperature | |

| Maximum operating power of a single air conditioner | |

| Maximum response rate | |

| Maximum daily continuous adjustment time | |

| Total duration of maximum response per day | |

| Maximum operating power of a single water heater | |

| Daily hot water energy consumption | |

| Maximum increased load in a single period | |

| Maximum load reduction in a single period | |

| Initial hot water energy storage state | |

| Battery capacity | |

| Initial state of charge | |

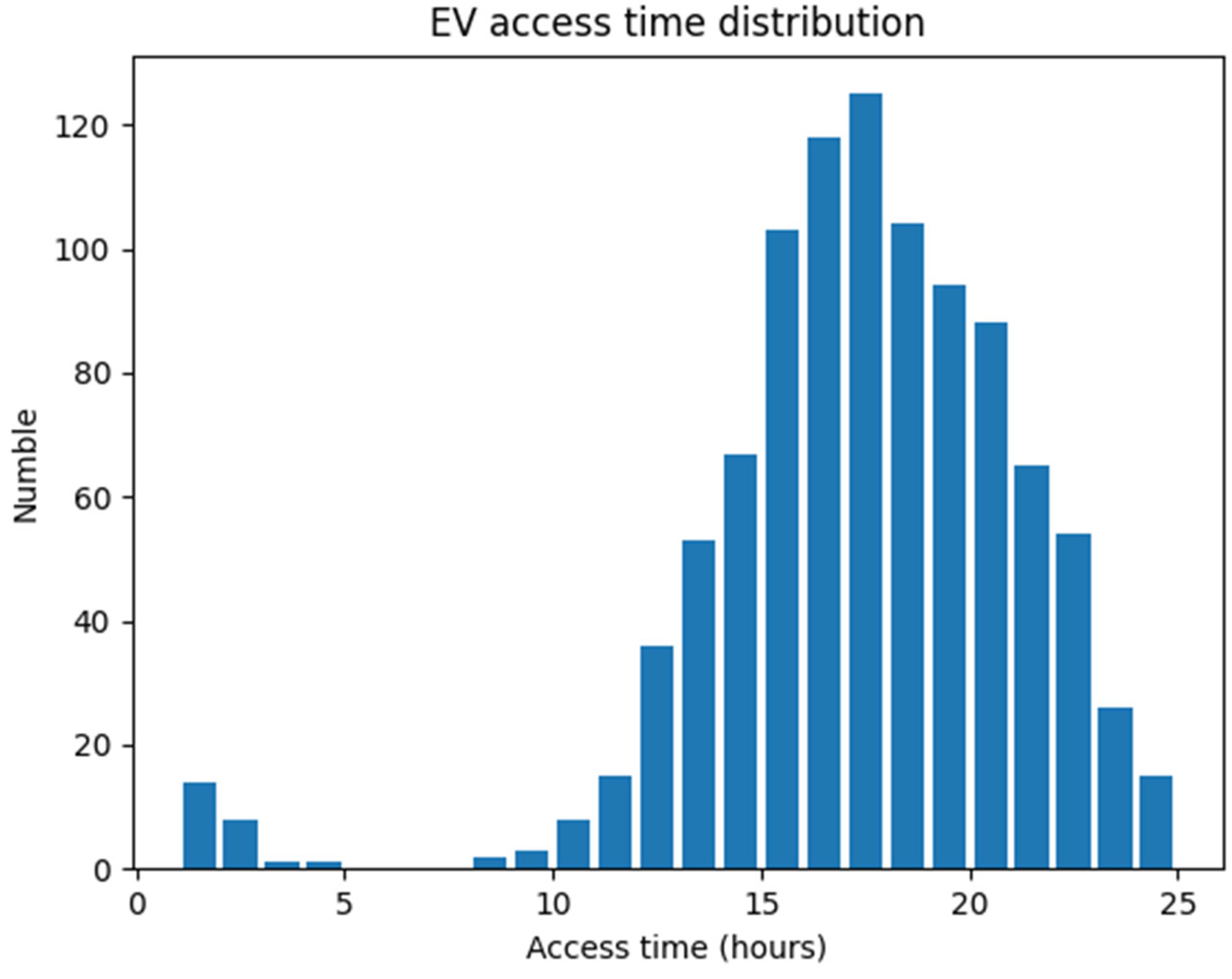

| Access time of electric vehicle | |

| Maximum discharge power | |

| Maximum charging power | |

| Expected final SOC | |

| Guaranteed SOC limit | |

| Rated capacity of energy storage unit | |

| Maximum SOC | |

| Minimum SOC | |

| Maximum charging power | |

| Maximum discharge power | |

| Energy storage charging efficiency | |

| Energy storage discharge efficiency |

Appendix A

| Algorithm A1 Feature Selection Algorithm Based on Maximum Correlation-Minimum Redundancy and Causality Screening |

| Input: Feature set , Target variable , Required feature number Significance level . |

| Output: Optimal feature subset after final screening. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix B

| Parameter Name | Description of Parameter | Parameter Range |

|---|---|---|

| User-set comfort temperature | 24 °C | |

| Comfortable temperature tolerance intervals | 2 °C | |

| Heat conduction efficiency | 0.2 | |

| Refrigeration rate | 0.5 °C/h | |

| Electricity price-response threshold | U (0.4, 0.5) | |

| User indoor temperature | U (20, 28) | |

| Outdoor temperature | Obtained from NWP data | |

| Maximum operating power of a single air conditioner | 2 kw | |

| Maximum response rate | 0.3 kw/h | |

| Maximum daily continuous adjustment time | 2 h | |

| Total duration of maximum response per day | 3 h |

| Parameter Name | Description of Parameter | Parameter Range |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum operating power of a single water heater | 2 kw | |

| Daily hot water energy consumption | 6 kwh | |

| Maximum increased load in a single period | 1 kw | |

| Maximum load reduction in a single period | 1 kw | |

| Single maximum continuous response time | 2 h | |

| Maximum cumulative response time per day | 3 h | |

| Maximum response rate | 0.3 kw/h | |

| Initial hot water energy storage state | U (0.3, 0.7) |

| Parameter Name | Description of Parameter | Parameter Range |

|---|---|---|

| Temp_center | Central temperature of membership function | [10, 20, 30] °C |

| Temp_std | Standard deviation of normal distribution in each temperature zone | [3, 5, 3] |

| Temp_weight | Influence weight of each temperature zone on access intention | [0.3, 1.0, 0.5] |

| N | Maximum number of electric vehicles | 1000 |

| Temperature | Actual ambient temperature | Obtained from NWP data |

| Parameter Name | Description of Parameter | Parameter Range |

|---|---|---|

| N | Maximum number of electric vehicles | 1000 |

| Battery capacity | Weighted discrete distribution | |

| Initial state of charge | U (0.2, 0.8) | |

| Access time of electric vehicle | Custom cumulative distribution function | |

| Maximum discharge power | 3.3 kw | |

| Maximum charging power | 3.3 kw | |

| Expected final SOC | 0.95 | |

| Guaranteed SOC limit | 0.5 |

| Parameter Name | Description of Parameter | Parameter Range |

|---|---|---|

| N | Number of energy storage units | 10 |

| Rated capacity of energy storage unit | U (500, 1400) | |

| Maximum SOC | 0.95 | |

| Minimum SOC | 0.05 | |

| Maximum charging power | 200 kw | |

| Maximum discharge power | 200 kw | |

| Initial SOC of energy storage | U (0.3, 0.7) | |

| Energy storage charging efficiency | 0.95 | |

| Energy storage discharge efficiency | 0.95 |

References

- Xu, C.X.; Chen, Z.X.; Zhu, W.J.; Zhi, J.Q.; Yu, Y.; Shi, C.F. Time-frequency spillover and early warning of climate risk in international energy markets and carbon markets: From the perspective of complex network and machine learning. Energy 2025, 318, 134857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yong, P.; Yu, J.; Yang, Z. Stacking algorithm based framework with strong generalization performance for ultra-short-term photovoltaic power forecasting. Energy 2025, 322, 135599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, R. Artificial intelligence in the renewable energy transition: The critical role of financial development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandes, B.; El Moursi, M.S.; Hatziargyriou, N.; El Khatib, S. A Review of Power System Flexibility with High Penetration of Renewables. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 3140–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, H.; Shami, H.O.; Moazzami, M.; Ahmadi, G.; Toghraie, D.; Rezaei, M.; Dolatshahi, M.; Salahshour, S. Design an integrated strategic resource planning to analyze the development of renewable energy sources. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.W.; Shin, J.S.; Kim, J.O. Operation Strategy of Multi-Energy Storage System for Ancillary Services. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 4409–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, K.; Gouda, P.K.; Rath, B.B.; Krishnamoorthy, M. Optimal day-ahead scheduling of microgrid equipped with electric vehicle and distributed energy resources: SFO-CSGNN approach. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 113933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Wang, Y.X.; Ni, J.N.; Zhang, H.D. Integration of smart buildings with high penetration of storage systems in isolated 100% renewable microgrids. J. Energy Storage 2025, 105, 114633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliasghari, P.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Alipour, M.; Abapour, M.; Zare, K. Optimal scheduling of plug-in electric vehicles and renewable micro-grid in energy and reserve markets considering demand response program. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, S.A.; Sreeram, V.; Iu, H.H. A review of coordination strategies and protection schemes for microgrids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostok, A.; Stanek, W. Thermo-ecological analysis of the power system based on renewable energy sources integrated with energy storage system. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemi, Z.; Tran, T.T.; Smith, A.D. Comparing classical and metaheuristic methods to optimize multi-objective operation planning of district energy systems considering uncertainties. Appl. Energy 2022, 321, 119400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E.S.; Serra, L.M.; Lázaro, A. Energy communities approach applied to optimize polygeneration systems in residential buildings: Case study in Zaragoza, Spain. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 82, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.T.; Hui, H.X.; Zhang, H.C.; Dai, N.Y.; Song, Y.H. Distributed Control of Large-Scale Inverter Air Conditioners for Providing Operating Reserve Based on Consensus with Nonlinear Protocol. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 15847–15857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, G.Q.; Zhao, D.B.; Tian, W. Optimal Scheduling of an Isolated Microgrid with Battery Storage Considering Load and Renewable Generation Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, P.; Mao, Z.; Diao, H.; Li, J.; Tu, C. Multi-layer control strategy to enhance the economy and stability of battery energy storage system in wind farms. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 169, 110776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ding, C.; Yan, C.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xue, F. Robust optimization method of power system multi resource reserve allocation considering wind power frequency regulation potential. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 155, 109599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Sun, Z.D.; Chen, Z.H. Development of energy management system based on a rule-based power distribution strategy for hybrid power sources. Energy 2019, 175, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Q. Optimal Scheduling Considering Demand Response Based on Multi-Energy Complementary Distributed Integrated Energy Management System. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Energy and Electrical Power Systems (ICEEPS), Guangzhou, China, 14–16 July 2024; pp. 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Cheng, B.; Xu, T.; Pan, J.; Chen, Y. Multi-level task network scheduling and electricity supply collaborative optimization under time-of-use electricity pricing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 203, 110952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, H.X.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.D.; Lin, Y.; Song, Y.H. Operating reserve evaluation of aggregated air conditioners. Appl. Energy 2017, 196, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.T.; Hui, H.X.; Zhang, H.C.; Dai, N.Y.; Song, Y.H. Event-Triggered Consensus Control of Large-Scale Inverter Air Conditioners for Demand Response. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 4954–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmousavi, S.A.; Patrick, S.N.; Nehrir, M.H. Real-Time Demand Response Through Aggregate Electric Water Heaters for Load Shifting and Balancing Wind Generation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, M.; Li, J.F.; Li, G.Y. Multi-area Generation-reserve Joint Dispatch Approach Considering Wind Power Cross-regional Accommodation. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2017, 3, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babahajiani, P.; Shafiee, Q.; Bevrani, H. Intelligent Demand Response Contribution in Frequency Control of Multi-Area Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.F.; Gu, W.; You, F.Q. Bilayer Distributed Optimization for Robust Microgrid Dispatch with Coupled Individual-Collective Profits. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, 12, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.; Vahidinasab, V.; Shafie-khah, M.; Catalao, J.P.S. Coordinated scheduling of energy storage systems as a fast reserve provider. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 130, 106941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laslett, D.; Carter, C.; Creagh, C.; Jennings, P. A large-scale renewable electricity supply system by 2030: Solar, wind, energy efficiency, storage and inertia for the South West Interconnected System (SWIS) in Western Australia. Renew. Energy 2017, 113, 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltsaklis, N.E.; Knápek, J. Integrated market scheduling with flexibility options. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 208, 115020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluhm, H.; Gährs, S. Environmental assessment of prosumer digitalization: The case of virtual pooling of PV battery storage systems. J. Energy Storage 2023, 59, 106487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Azuma, S.; Yamaguchi, N.; Yamashita, Y. Design and Value Evaluation of Demand Response Based on Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 4809–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, R.N.; Yang, Z. Optimal Scheduling of Isolated Microgrids Using Automated Reinforcement Learning-Based Multi-Period Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.W.; Tan, Z.F.; Yuan, J.Y.; Tan, Q.K.; Li, H.H.; Dong, F.G. A bi-level stochastic scheduling optimization model for a virtual power plant connected to a wind-photovoltaic-energy storage system considering the uncertainty and demand response. Appl. Energy 2016, 171, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, N.; Pezhmani, Y.; Khazali, A. Economic-environmental risk-averse optimal heat and power energy management of a grid-connected multi microgrid system considering demand response and bidding strategy. Energy 2022, 240, 122844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribó-Pérez, D.; Carrión, A.; García, J.R.; Bel, C.A. Ex-post evaluation of Interruptible Load programs with a system optimisation perspective. Appl. Energy 2021, 303, 117643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi-Taghiabadi, S.M.; Sedighizadeh, M.; Zangiabadi, M.; Fini, A.S. Integration of wind generation uncertainties into frequency dynamic constrained unit commitment considering reserve and plug in electric vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Watson, J.P.; Guan, Y.P. Multi-Stage Robust Unit Commitment Considering Wind and Demand Response Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 2708–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkan, R.; Ilinca, A.; Ghorbanzadeh, M. A genetic algorithm optimization approach for smart energy management of microgrid. Renew. Energy 2022, 197, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazidi, M.; Zakariazadeh, A.; Jadid, S.; Siano, P. Integrated scheduling of renewable generation and demand response programs in a microgrid. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 86, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.Y.; Guo, C.X.; Chen, Z. Frequency Constrained Dispatch with Energy Reserve and Virtual Inertia from Wind Turbines. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2025, 16, 1340–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Jahangir, H.; Vatandoust, B.; Golkar, M.A.; Ahmadian, A.; Elkamel, A. Optimal bidding strategy of a virtual power plant in day-ahead energy and frequency regulation markets: A deep learning-based approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 127, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassar, A.A.A. Short-Term Energy Forecasting to Improve the Estimation of Demand Response Baselines in Residential Neighborhoods: Deep Learning vs. Machine Learning. Buildings 2024, 14, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.H.; Yang, C.; Han, L.J.; Wang, W.D.; Ma, Y.; Xiang, C.L. Power reserve predictive control strategy for hybrid electric vehicle using recognition-based long short-term memory network. J. Power Sources 2022, 520, 230865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.D.; Chen, H.B.; Jin, T. A new optimization approach considering demand response management and multistage energy storage: A novel perspective for Fujian Province. Renew. Energy 2024, 220, 119621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.B.; Wang, J.Y.; Chen, H.X.; Li, G.N.; Liu, J.Y.; Xu, C.L.; Huang, R.G.; Huang, Y. Machine learning-based thermal response time ahead energy demand prediction for building heating systems. Appl. Energy 2018, 221, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.B.; Chen, Z.Q.; Cheng, L.; Liu, X.F. Energy data generation with Wasserstein Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks. Energy 2022, 257, 124694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangon, J. Climate-Proofing Critical Energy Infrastructure: Smart Grids, Artificial Intelligence, and Machine Learning for Power System Resilience against Extreme Weather Events. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2024, 30, 03124001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.L.; Xu, Q.S.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.B.; Sun, L. Day-ahead and intra-day optimization for energy and reserve scheduling under wind uncertainty and generation outages. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 195, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.P.; Lu, F.; Cheng, Y.P. Study on Reserve Capacity Optimization Model of Wind and Solar Power Generation System Based on Multi-Objective Optimization. In Proceedings of the 4th National Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (NCEECE), Xi’an, China, 12–13 December 2016; pp. 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, F.; Wörner, S.; Lygeros, J. Ramp-rate-constrained bidding of energy and frequency reserves in real market settings. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03892. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Li, W.; Feng, Z.; Bai, W.; Jia, L.; Wei, Z. Economic Dispatch Model of High Proportional New Energy Grid-Connected Consumption Considering Source Load Uncertainty. Energies 2023, 16, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.F.; Zhao, Y.H.; Yang, Y.W.; Zhang, L.T.; Ju, C. Demand-Response-Oriented Load Aggregation Scheduling Optimization Strategy for Inverter Air Conditioner. Energies 2023, 16, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.Y.; Li, Z.W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Guo, Y.F.; Song, S. Model of Electric Water Heater and Influencing factors Analysis of Frequency Regulation Response Capability on Demand Side. In Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Beijing, China, 7–9 September 2019; pp. 827–833. [Google Scholar]

- Gabaldón, A.; García-Garre, A.; Ruiz-Abellón, M.C.; Guillamón, A. Modeling and Aggregation of Electric Water Heaters for the Development of Demand Response Using Grey Box Models. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, L.X.; Pan, T. Optimized Configuration of Distributed Power Generation Based on Multi-Stakeholder and Energy Storage Synergy. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 129773–129787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonder, H.B.; Cipcigan, L.; Loo, C.U. Using Electric Vehicles and Demand Side Response to Unlock Distribution Network Flexibility. In Proceedings of the IEEE Milan PowerTech Conference, Milan, Italy, 23–27 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Qian, K.; Allan, M.; Zhou, W. Modeling of the Cost of EV Battery Wear Due to V2G Application in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2011, 26, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhi, K.; Abate, A. An exact characterisation of flexibility in populations of electric vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2023 62nd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Singapore, 13–15 December 2023; pp. 6582–6587. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J. Solar and wind power data from the Chinese State Grid Renewable Energy Generation Forecasting Competition. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Key Focus | Limitations | Our Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| MILP/Robust Optimization/Two-stage Stochastic Optimization [22,23,24] | Physical modeling and coordinated scheduling | High computational cost; difficult for large-scale systems; limited online adaptability | Combines physical modelling with data-driven approach for scalable, flexible assessment |

| GRU/LSTM/RNN/RF/XGBoost/LightGBM [27,28,29,30,31] | Data-driven prediction of reserve capacity | High dependence on data quality; may lack interpretability and physical constraints | Uses mRMR + Granger causality for feature selection; stacking ensemble improves accuracy and generalization |

| Existing meteorology-aware methods [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] | Impact of weather on reserve | Often single-resource focused; limited multi-source integration | Proposes multi-source, meteorology-aware integrated framework for distributed resources |

| Stacking with mRMR and Granger | Integrated prediction and evaluation under meteorological uncertainty | / | Provides planning and operational decision-support; handles multi-source, high-dimensional, nonlinear, weather-perturbed data; improves interpretability and generalization |

| Feature Name | Average Mutual Information | Feature Sorting | F Value Up | p Value Up | F Value Down | p Value Down |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WindSpeed_wheel | 0.335 | 7 | 0.024 | 0.998 | 3.657 | 0.026 ** |

| Wind_temperature | 0.101 | 10 | 2.991 | 0.018 ** | 3.816 | 0.010 *** |

| Wind_Atmosphere | 0.025 | 3 | 7.354 | 0.007 *** | 3.249 | 0.011 ** |

| Wind_humidity | 0.071 | 5 | 2.257 | 0.080 * | 1.906 | 0.126 |

| Direct irradiance | 0.269 | 8 | 0.834 | 0.361 | 1.210 | 0.298 |

| Global irradiance | 0.269 | 6 | 0.833 | 0.361 | 1.213 | 0.297 |

| Solar_temperature | 0.115 | 2 | 5.233 | 0.000 *** | 4.848 | 0.028 ** |

| Solar_Atmosphere | 0.019 | 4 | 1.831 | 0.139 | 3.940 | 0.020 ** |

| WindPower | 0.335 | 1 | 1.637 | 0.195 | 4.044 | 0.018 ** |

| Model | Parameter Setting | Model | Parameter Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| LightGBM | The number of leaf nodes is 100; tree depth 5; the learning rate is 0.01; L1 regularization coefficient is 0.1; L2 regularization 0.95 | GBR | The number of trees is 100; Tree depth 5; The learning rate is 0.1; minimum sample 1 of leaf node; minimum sample of internal division node 2 |

| XGBoost | The number of trees is 100; tree depth 5; L1 regularization coefficient is 0.1; L2 regularization 0.95; sample weight sum 2 | KNN | Number of neighbours 10; neighbour weight is uniform; calculate neighbour method auto |

| CatBoost | The number of trees is 100; the learning rate is 0.1; tree depth 5; L2 regularization coefficient 3; number of buckets 32 | MLP | The number of neurons in the first layer is 16, the number of neurons in the second layer is 16, the learning rate is 0.05, and the batch size is 64 |

| SVR | The kernel function is Gaussian kernel; ε parameter 0.1; penalty parameter 1 | Bay | The convergence threshold 1 × 10−6 and the prior parameters are 1 × 10−6 |

| KAN | The number of neurons is 32, the learning rate is 0.01 and the batch size is 64 | RNN | The number of neurons in the first layer is 64, the number of neurons in the second layer is 64, the learning rate is 0.01, and the batch size is 64 |

| RF | The number of trees is 100; tree depth 5; minimum sample 1 of leaf node; minimum sample of internal division node 2 | LSTM | The number of neurons in the first layer is 64, the number of neurons in the second layer is 64, the learning rate is 0.01, and the batch size is 64 |

| DT | Tree depth 5; minimum sample 1 of leaf node; minimum sample 2 of internal division nodes | GRU | The number of neurons in the first layer is 64, the number of neurons in the second layer is 64, the learning rate is 0.01, and the batch size is 64 |

| Model Name | MSE | RMSE | MAE | MAPE | R2 | Time(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-BiLSTM | 700.331 | 26.464 | 16.828 | 0.749 | 0.997 | 784.48 |

| CNN-BiGRU | 710.784 | 26.661 | 16.051 | 0.771 | 0.997 | 708.18 |

| CNN-LSTM-Attention | 1223.485 | 34.978 | 24.703 | 1.247 | 0.995 | 545.69 |

| CNN-GRU-Attention | 891.424 | 29.857 | 17.800 | 0.857 | 0.997 | 507.81 |

| LSTM-KAN | 3313.508 | 57.563 | 30.169 | 0.009 | 0.986 | 70.11 |

| GRU-KAN | 2816.502 | 53.071 | 28.957 | 0.009 | 0.988 | 69.41 |

| Our | 966.761 | 31.093 | 19.382 | 0.919 | 0.996 | 130.85 |

| Model Name | MSE | RMSE | MAE | MAPE | R2 | Time(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-BiLSTM | 3698.212 | 60.813 | 47.686 | 1.072 | 0.993 | 758.97 |

| CNN-BiGRU | 3975.014 | 60.048 | 50.231 | 1.126 | 0.992 | 691.93 |

| CNN-LSTM-Attention | 4246.426 | 65.165 | 47.732 | 1.052 | 0.991 | 534.33 |

| CNN-GRU-Attention | 4237.599 | 65.097 | 49.614 | 1.118 | 0.991 | 497.55 |

| LSTM-KAN | 15,052.415 | 122.688 | 71.416 | 0.012 | 0.969 | 74.90 |

| GRU-KAN | 16,897.812 | 129.992 | 76.529 | 0.013 | 0.966 | 70.36 |

| Our model | 4317.625 | 65.709 | 50.057 | 1.140 | 0.991 | 133.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, C.; Wei, B.; Chen, Y.; Kuang, F.; Yong, P.; Chen, Z. Operational Flexibility Assessment of Distributed Reserve Resources Considering Meteorological Uncertainty: Based on an End-to-End Integrated Learning Approach. Processes 2025, 13, 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123870

Gao C, Wei B, Chen Y, Kuang F, Yong P, Chen Z. Operational Flexibility Assessment of Distributed Reserve Resources Considering Meteorological Uncertainty: Based on an End-to-End Integrated Learning Approach. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123870

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Chao, Bin Wei, Yabin Chen, Fan Kuang, Pei Yong, and Zixu Chen. 2025. "Operational Flexibility Assessment of Distributed Reserve Resources Considering Meteorological Uncertainty: Based on an End-to-End Integrated Learning Approach" Processes 13, no. 12: 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123870

APA StyleGao, C., Wei, B., Chen, Y., Kuang, F., Yong, P., & Chen, Z. (2025). Operational Flexibility Assessment of Distributed Reserve Resources Considering Meteorological Uncertainty: Based on an End-to-End Integrated Learning Approach. Processes, 13(12), 3870. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123870