Review of Wood Sawdust Pellet Biofuel: Preliminary SWOT and CAME Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

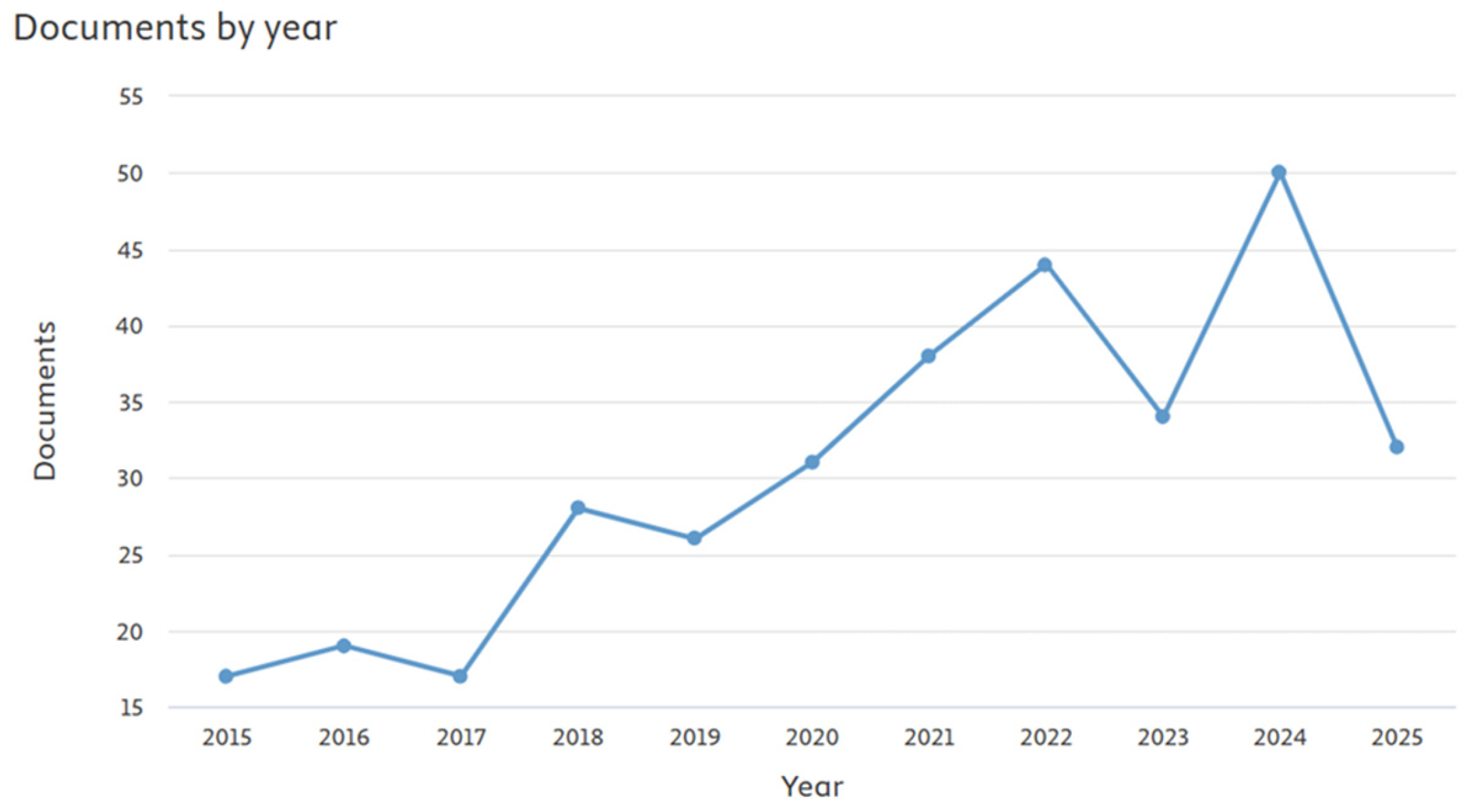

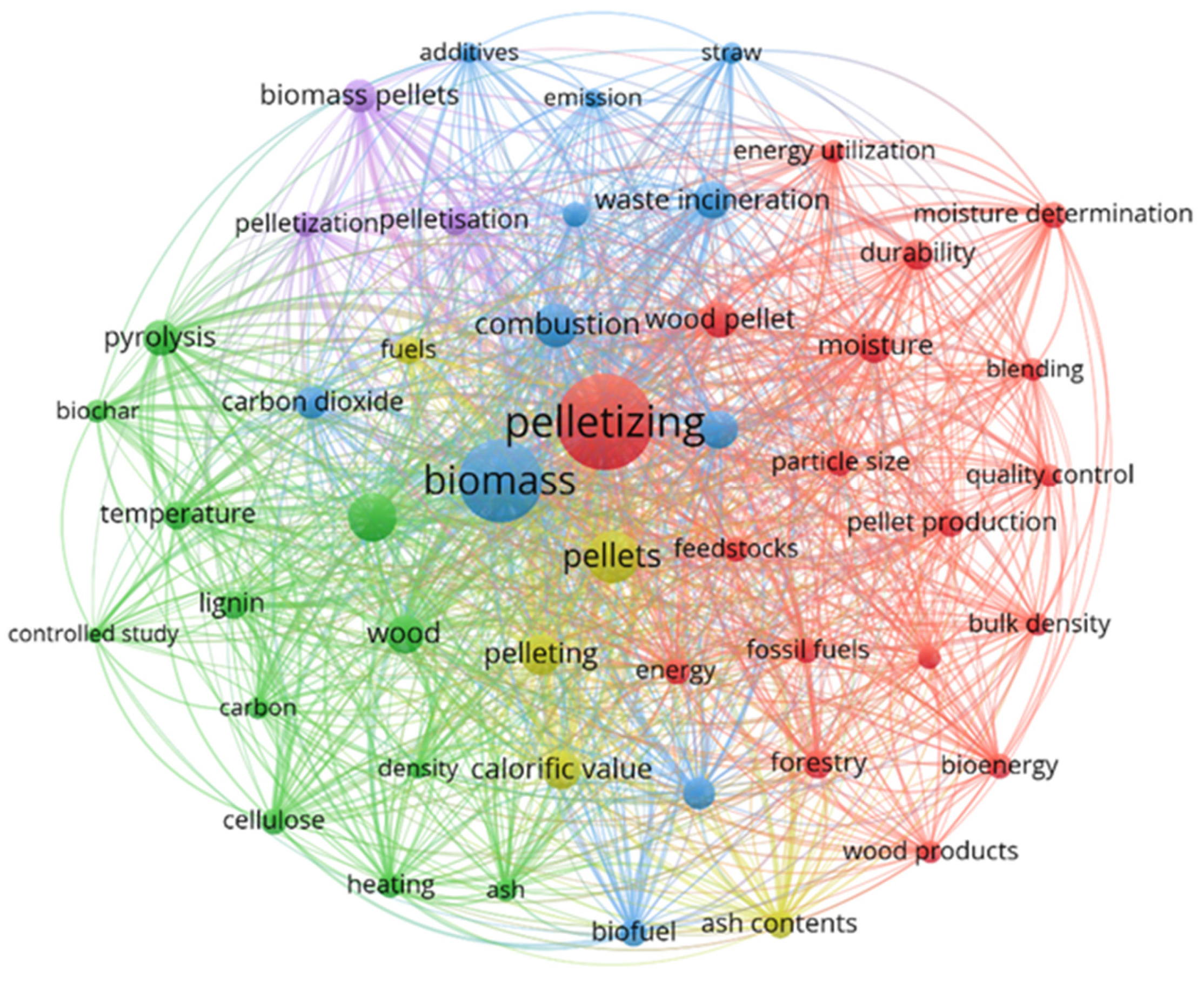

2. Methodology

- How can wood sawdust be effectively used as a biofuel?

- How or where is wood sawdust obtained from?

- Is it better to use sawdust in its natural form or in pellet form?

- What is the formation process for sawdust pellets?

- What calculation tools are used in wood sawdust combustion?

3. Obtention and Processing

4. Pelletisation

5. Combustion Modelling

5.1. Drying

| Case Study | Application of Darcy’s Law | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-particle heat transfer during biomass torrefaction | To model flow velocity within a porous wood cylinder | [59] |

| Single pellet smouldering combustion | Heat and species transport within the porous matrix of a pellet | [58] |

| Pressure drop in packed beds of wood particles | Darcy’s law extended with the Forchheimer equation to understand the flow in lignocellulosic porous media | [60] |

| Flow through woodchip media | Describe the flow in biomass porous media and its applicability limits | [61] |

| pressure drop in gasifier beds | Darcy’s principle applied with the Ergun equation to predict pressure drop in fixed beds of cylindrical biomass pellets | [62] |

5.2. High Heating Values

5.3. Ash Content

| Model Approach | Analysis Type | Complementary Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy, mass, and momentum conservation for each particle | Combustion in a fixed bed | Particle–particle interaction and particle–gas phase interaction | [75] |

| Particle size distribution, Turbulent particle dispersion, Radiant heat transfer, Pyrolysis, Volatile combustion, Gas phase conversion rate | Numerical analysis of pulverised biomass | RANS, Eddy Dissipation, and Kinetic control | [81] |

| Heat/mass transfer, Turbulent flow, Gas–particle flow interaction, Homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions | Wood chip gasification considering heat/mass transfer, turbulent flow, and gas–particle interactions | -- | [82] |

| DEM | Solid fuel movement and conversion, Interaction with the surrounding gas phase | CFD | [83] |

| Heat and mass transfer, Pyrolysis, Homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions, Radiation, Gas-phase discrete particle interactions | Biomass gasification in a high-temperature entrained flow reactor calculates heat and mass transfer, pyrolysis, and gas-phase particle interactions | -- | [80] |

| Kinetic modelling | Combustion in a conical spouted bed reactor, coupling intrinsic kinetics with the gas flow patterns | Compartmental model for gas flow | [84] |

6. SWOT Analysis

6.1. Techno-Economic Aspects

6.2. Preliminary Analysis

6.3. Circular Economy

| SWOT Element | Analysis | References |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Abundance, Environmental benefits, Good energy density in Pellet format, Mature Research and Development Opportunities | [38,49,92] |

| Weaknesses | Variability of Raw Material, Presence of Contaminants and Need for Treatment, Density Sensitivity of Pellet Compression, and Complexity for Numerical Modelling | [93,94,95] |

| Opportunities | Contribution to Climate Change Mitigation, Growing Global Demand for Biofuels, Economic Viability and Cost Reduction, Integration into the Circular Economy | [96,97,98,99] |

| Threats | Presence of impurities, Pellet fragility, Ash and Solid Waste Management, Raw Material Variability and its Logistics Implications | [74,100,101,102] |

7. CAME Analysis

| LCA Category | Analysis | References |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Global Warming Potential | Considered “almost zero” | [111,112] |

| (b) Ozone Depletion | Lower effect vs. wood logs | [113,114] |

| (c) Particulate Matter Formation | Lower formation vs. wood logs | [114] |

| (d) Acidification & Eutrophication | Lower environmental impacts vs. fossil fuels | [113] |

| (e) Fossil Fuel Depletion | Contribution to avoiding depletion | [113] |

| (f) Life Cycle Impacts. | “Cradle to grave” | [112] |

8. Discussion

9. Identified Gaps

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scarsella, M.; de Caprariis, B.; Damizia, M.; De Filippis, P. Heterogeneous Catalysts for Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Review. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 140, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.K. The Synergy Effect through Combination of the Digital Economy and Transition to Renewable Energy on Green Economic Growth: Empirical Study of 18 Latin American and Caribbean Countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Appels, L.; Tan, T.; Dewil, R. Bioethanol from Lignocellulosic Biomass: Current Findings Determine Research Priorities. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 298153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzenberger, J.; Kranzl, L.; Tromborg, E.; Junginger, M.; Daioglou, V.; Sheng Goh, C.; Keramidas, K. Future Perspectives of International Bioenergy Trade. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 926–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, N.M.; González, G.; Mendieta, C.M.; Kruyeniski, J.; Área, M.C.; Vallejos, M.E. Biomass Waste as Sustainable Raw Material for Energy and Fuels. Multidiscip. Digit. Publ. Inst. 2021, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunerová, A.; Roubík, H.; Brožek, M.; Herák, D.; Šleger, V.; Mazancová, J. Potential of Tropical Fruit Waste Biomass for Production of Bio-Briquette Fuel: Using Indonesia as an Example. Energies 2017, 10, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imberti, R.M.; Carvalho Padilha, J.; da Silva Arrieche, L. Production of Sawdust and Chicken Fat Briquettes as an Alternative Solid Fuel. Renew. Energy 2024, 228, 120638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Rezaei, H.; Banadkoki, O.G.; Panah, F.Y.; Sokhansanj, S. Variability in Physical Properties of Logging and Sawmill Residues for Making Wood Pellets. Processes 2024, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendi, J.; Garniwa, I. Engineering and Economic Analysis of Sawdust Biomass Processing as a Co-Firing Fuel in Coal-Fired Power Plant Boiler Pulverized Coal Type. J. Pendidik. Teknol. Kejuru. 2022, 5, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürcher, E. Les Arbres, Entre Visible et Invisible: S’étonner, Comprendre, Agir; Actes Sud Éditions: Arles, France, 2021; ISBN 978-2-330-06594-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rominiyi, O.L.; Adaramola, B.; Ikumapayi, O.M.; Oginni, O.T.; Akinola, S.A. Potential Utilization of Sawdust in Energy, Manufacturing and Agricultural Industry; Waste to Wealth. World J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 5, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefisan, O.O.; McDonald, A.G. Evaluation of Wood Plastic Composites Produced from Mahogany and Teak. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2017, 4, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwango, A.; Kambole, C. Engineering Characteristics and Potential Increased Utilisation of Sawdust Composites in Construction—A Review. J. Build. Constr. Plan. Res. 2019, 7, 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, R.; Paczkowski, S.; Knappe, V.; Russ, M.; Wöhler, M.; Pelz, S. Effect of Feedstock Particle Size Distribution and Feedstock Moisture Content on Pellet Production Efficiency, Pellet Quality, Transport and Combustion Emissions. Fuel 2019, 263, 116662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Armenta, R.M.; Ruelas-Ayala, R.D.; Sañudo-Torres, R.R.; Félix-Herrán, J.A. El Compostaje de Residuos Sólidos Orgánicos y Su Efecto En Especies Forestales de Importancia Económica En El Norte de Sinaloa. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2025, 41, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Mendoza, M.E.; Ruiz-Aquino, F.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G.; Feria-Reyes, R.; Santiago-García, W.; Suárez-Mota, M.E.; Puc-Kauil, R.; Gabriel-Parra, R. Chemical and Energetic Evaluation of Densified Biomass of Quercus Laurina and Quercus Rugosa for Bioenergy Production. Forests 2025, 16, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, N.; Razali, S.M.; Sulaiman, M.S.; Edin, T.; Wahab, R.A. Converting Wood-Related Waste Materials into Other Value-Added Products: A Short Review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1053, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorineschi, L.; Cascini, G.; Rotini, F.; Tonarelli, A. Versatile Grinder Technology for the Production of Wood Biofuels. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 197, 106217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, P.; Mupondwa, E.; Tabil, L.G.; Li, X.; Cree, D. Life Cycle Assessment of Bioenergy Production from Wood Sawdust. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 138936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, M.J.; Krzyżaniak, M.; Olba-Zięty, E. Properties of Pellets from Forest and Agricultural Biomass and Their Mixtures. Energies 2025, 18, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichsan, A.C.; Ningsih, R.V.; Rini, D.S.; Webliana, K. Combustion Performance and Physicochemical Characteristics of Sawdust-Based Bio-Charcoal Briquettes Using Molasses Adhesive. J. Sylva Lestari 2025, 13, 578–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrän, D.; Schaubach, K.; Peetz, D.; Junginger, M.; Mai-Moulin, T.; Schipfer, F.; Olsson, O.; Lamers, P. The Dynamics of the Global Wood Pellet Markets and Trade—Key Regions, Developments and Impact Factors. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2018, 13, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirilenko, A.; Sedjo, R.A. Climate Change Impacts on Forestry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19697–19702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, A.; Marchi, E.; Spinelli, R.; Brink, M. Past, Present and Future of Industrial Plantation Forestry and Implication on Future Timber Harvesting Technology. J. For. Res. 2019, 31, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matikeeva, N.; Kozlenko, A.; Karybekova, S.; Tokoeva, A.; Kamalova, A. Forest Ecosystems in the Context of a Green Economy: Potential for Sustainable Energy. Ukr. J. For. Wood Sci. 2025, 16, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetemäki, L.; Palahí, M.; Nasi, R. Seeing the Wood in the Forests; Knowledge to Action; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2020.

- Latterini, F.; Mederski, P.S.; Jaeger, D.; Venanzi, R.; Tavankar, F.; Picchio, R. The Influence of Various Silvicultural Treatments and Forest Operations on Tree Species Biodiversity. Curr. For. Rep. 2023, 9, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppi, P.E.; Stål, G.; Arnesson-Ceder, L.; Hallberg-Sramek, I.; Hoen, H.F.; Svensson, A.; Wernick, I.K.; Högberg, P.; Lundmark, T.; Nordin, A. Managing Existing Forests Can Mitigate Climate Change. For. Ecol. Manage. 2022, 513, 120186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, J.H.; Wamsley, M.J.; Perry, J.M. Moisture Content of Baled Forest and Urban Woody Biomass during Long-Term Open Storage. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2018, 34, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrique de Almeida, D.; Hendrigo de Almeida, T.; Salles Ferro, F.; Chahud, E.; Antonio Melgaço Nunes Branco, L.; Luís Christoforo, A.; Antonio Rocco Lahr, F. Analysis of Solid Waste Generation in a Wood Processing Machine. Int. J. Agric. For. 2017, 7, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałubicki, B.; Hlásková, L.; Frömel-Frybort, S.; Rogoziński, T. Feed Force and Sawdust Geometry in Particleboard Sawing. Materials 2021, 14, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orłowski, K.A.; Chuchała, D.; Przybyliński, T.; Legutko, S. Recovering Evaluation of Narrow-Kerf Teeth of Mini Sash Gang Saws. Materials 2021, 14, 7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wzorek, M.; Król, A.; Junga, R.; Małecka, J.; Yılmaz, E.; Kolasa-Więcek, A. Effect of Storage Conditions on Lignocellulose Biofuels Properties. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chockalingam, M.P.; Dhanushkodi, S.; Sudhakar, K.; Wilson, D.V. Industrial and Small-Scale Biomass Dryers: An Overview. Energy Eng. 2021, 118, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pędzik, M.; Przybylska-Balcerek, A.; Szwajkowska-Michałek, L.; Szablewski, T.; Rogoziński, T.; Buśko, M.; Stuper-Szablewska, K. The Dynamics of Mycobiota Development in Various Types of Wood Dust Depending on the Dust Storage Conditions. Forests 2021, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, G.; De Francesco, C.; Gasperini, T.; Fabrizi, S.; Duca, D.; Ilari, A.; De Francesco, C.; Gasperini, T.; Fabrizi, S.; Duca, D.; et al. Quality Assessment and Classification of Feedstock for Bioenergy Applications Considering ISO 17225 Standard on Solid Biofuels. Resources 2023, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda-Cepeda, C.O.; Goche-Télles, J.R.; Palacios-Mendoza, C.; Moreno-Anguiano, O.; Núñez-Retana, V.D.; Heya, M.N.; Carrillo-Parra, A. Effect of Sawdust Particle Size on Physical, Mechanical, and Energetic Properties of Pinus Durangensis Briquettes. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17225-1:2021; Solid Biofuels—Fuel Specifications and Classes Part 1: General Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/76087.html (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- UNE-EN 14918; Biocombustibles Sólidos. Determinación Del Poder Calorífico. Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR): Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- Branco, V.; Costa, M. Effect of Particle Size on the Burnout and Emissions of Particulate Matter from the Combustion of Pulverized Agricultural Residues in a Drop Tube Furnace. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 149, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, B.; Tascón, A.; Amez, I.; Fernandez-Anez, N. Influence of Particle Size on the Flammability and Explosibility of Biomass Dusts: Is a New Approach Needed? Fire Technol. 2023, 59, 2989–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karinkanta, P.; Illikainen, M.; Niinimäki, J. Pulverisation of Dried and Screened Norway Spruce (Picea abies) Sawdust in an Air Classifier Mill. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 44, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchio, R.; Latterini, F.; Venanzi, R.; Stefanoni, W.; Suardi, A.; Tocci, D.; Pari, L. Pellet Production from Woody and Non-Woody Feedstocks: A Review on Biomass Quality Evaluation. Energies 2020, 13, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, M.; Jewiarz, M.; Mudryk, K.; Knapczyk, A. Influence of Raw Material Drying Temperature on the Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Biomass Agglomeration Process—A Preliminary Study. Energies 2020, 13, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styks, J.; Wróbel, M.; Frączek, J.; Knapczyk, A. Effect of Compaction Pressure and Moisture Content on Quality Parameters of Perennial Biomass Pellets. Energies 2020, 13, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhén, C.; Gref, R.; Sjöstróm, M.; Wästerlund, I. Effects of Raw Material Moisture Content, Densification Pressure and Temperature on Some Properties of Norway Spruce Pellets. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 87, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilvari, H.; de Jong, W.; Schott, D. Breakage Behavior of Biomass Pellets: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Comput. Part. Mech. 2020, 8, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenda, M.; Horabik, J.; Parafiniuk, P.; Oniszczuk, A.; Bańda, M.; Wajs, J.; Gondek, E.; Chutkowski, M.; Lisowski, A.; Wiącek, J.; et al. Mechanical and Combustion Properties of Agglomerates of Wood of Popular Eastern European Species. Materials 2021, 14, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurila, J.; Havimo, M.; Lauhanen, R. Compression Drying of Energy Wood. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 124, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.Y.; Lam, P.S.; Sokhansanj, S.; Bi, X.; Lim, C.J.; Melin, S. Effects of Pelletization Conditions on Breaking Strength and Dimensional Stability of Douglas Fir Pellet. Fuel 2013, 117, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, Z.; Csanády, E. Study on Energy Requirement of Wood Chip Compaction. Drv. Ind. 2015, 66, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggerstedt, K.; Wang, X. Experimental Investigation of Biomass Pellets and Pelletizing Process Using Hardwood and Switchgrass. In Proceedings of the ASME 2014 8th International Conference on Energy Sustainability collocated with the ASME 2014 12th International Conference on Fuel Cell Science, Engineering and Technology, Boston, MA, USA, 30 June–2 July 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, C.; Ferreira, T.; Marques, E.; Almeida, D.; Pereira, C.; Paiva, J.M. Steady State Fixed Bed Combustion of Wood Pellets. A Simple Theoretical Model. Rev. Eng. Térmica 2014, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, S.; Oh, J.-H.; Euh, S.-H.; Kim, D.H.; Yu, L. Simulation Study for Pneumatic Conveying Drying of Sawdust for Pellet Production. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 1142–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arous, S.; Koubaa, A.; Bouafif, H.; Bouslimi, B.; Braghiroli, F.L.; Bradaï, C. Effect of Pyrolysis Temperature and Wood Species on the Properties of Biochar Pellets. Energies 2021, 14, 6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C.; Monedero, E.; Lapuerta, M.; Portero, H. Effect of Moisture Content, Particle Size and Pine Addition on Quality Parameters of Barley Straw Pellets. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 92, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfelice, G.; Canu, P. On the Mechanism of Single Pellet Smouldering Combustion. Fuel 2021, 301, 121044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okekunle, P.O. Modelling and Simulation of Intra-Particle Heat Transfer during Biomass Torrefaction in a Fixed-Bed Reactor. Biofuels 2019, 13, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhofer, M.; Govaerts, J.; Parmentier, N.; Jeanmart, H.; Helsen, L. Experimental Investigation of Pressure Drop in Packed Beds of Irregular Shaped Wood Particles. Powder Technol. 2010, 205, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghane, E.; Fausey, N.R.; Brown, L.C. Non-Darcy Flow of Water through Woodchip Media. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 3400–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, D.S.; Chmielewski, J.K.; Yang, W. Pressure Drop Prediction of a Gasifier Bed with Cylindrical Biomass Pellets. Appl. Energy 2013, 113, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Qi, G.; Dong, P. A Granular-Biomass High Temperature Pyrolysis Model Based on the Darcy Flow. Front. Earth Sci. 2014, 9, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, O.S.; Jiang, L.; Buchireddy, P.; Barskov, S.O.; Guillory, J.L.; Holmes, W.E. Investigation of Effect of Biomass Torrefaction Temperature on Volatile Energy Recovery Through Combustion. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2018, 140, 112003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matali, S.; Rahman, N.A.; Idris, S.S.; Ya’acob, N.; Alias, A.B. Lignocellulosic Biomass Solid Fuel Properties Enhancement via Torrefaction. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasheva, S.; Dimov, M.; Fidan, H.; Stankov, S.; Lazarov, L.; Bozadzhiev, B.; Simitchiev, A.; Stoyanova, A. Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters of Biomass from Black Pine (Pinus nigra ARN.). E3S Web Conf. 2021, 327, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charis, G.; Danha, G.; Muzenda, E. Characterizations of Biomasses for Subsequent Thermochemical Conversion: A Comparative Study of Pine Sawdust and Acacia Tortilis. Processes 2020, 8, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Retana, V.D.; Serna, R.R.; Prieto-Ruíz, J.Á.; Wehenkel, C.; Carrillo-Parra, A. Improving the Physical, Mechanical and Energetic Properties of Quercus spp. Wood Pellets by Adding Pine Sawdust. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amrullah, A.; Syarif, A.; Fauzianur, A. Assessment of Combustion Behaviour of Carbonize Bio-Briquette Wood Residue under Different Pressure and Particle Size. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1034, 12080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubov, V.K.; Popov, A.N.; Popova, E.I. Combustion of Wood Pellets with a High Amount of Fines. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1211, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.A.; Brown, R.C. Oxidation Kinetics of Biochar from Woody and Herbaceous Biomass. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, T.L.; Hui, P.; Groom, L.H.; So, C. Characterization and Partitioning of the Char Ash Collected after the Processing of Pine Wood Chips in a Pilot-Scale Gasification Unit. In Woody Biomass Utilization: Proceedings of the International Conference on Woody Biomass Utilization, Starkville, MS, USA, 4–5 August 2009; Forest Products Society: Starkville, MS, USA, 2011; pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tumuluru, J.S.; Sokhansanj, S.; Lim, C.J.; Bi, T.; Lau, A.; Melin, S.; Sowlati, T.; Oveisi, E. Quality of Wood Pellets Produced in British Columbia for Export. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2010, 26, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Catrina, G.A.; Covaliu, C.I.; Luoana, F.; Cristea, I.; Serbanescu, A.; Cernica, G. Characterization of Different Types of Biomass Wastes Using Thermogravimetric and ICP-MS Analyses. Rev. Chim. 2020, 70, 4594–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, A.H.; Markovic, M.; Peters, B.; Brem, G. An Experimental and Numerical Study of Wood Combustion in a Fixed Bed Using Euler–Lagrange Approach (XDEM). Fuel 2015, 150, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.R.; Abdullah, N.; Rais, A.R.M. The Discrete Phase Modelling Governing the Dynamics of Biomass Particles Inside a Fast Pyrolysis Reactor. J. Phys. Sci. 2020, 31, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.A.; Porteiro, J.; Patiño, D.; Míguez, J.L. Eulerian CFD Modelling for Biomass Combustion. Transient Simulation of an Underfeed Pellet Boiler. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 101, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.A.; Martín, R.; Collazo, J.; Porteiro, J. CFD Steady Model Applied to a Biomass Boiler Operating in Air Enrichment Conditions. Energies 2018, 11, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandro, D.; Zaleta-Aguilar, A.; Rangel-Hernández, V.H.; Olivares-Arriaga, A. Numerical Simulation of a Pilot-Scale Reactor under Different Operating Modes: Combustion, Gasification and Pyrolysis. Biomass Bioenergy 2018, 116, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, X.; Li, T.; Løvås, T. Eulerian–Lagrangian Simulation of Biomass Gasification Behavior in a High-Temperature Entrained-Flow Reactor. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 5184–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal, C.D.; Böke, Y.E.; Benim, A.C. Numerical Analysis of Pulverized Biomass Combustion. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 321, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Li, G.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y. Euler–Lagrange Modeling of Wood Chip Gasification in a Small-Scale Gasifier. J. Energy Inst. 2014, 88, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, J.; Wissing, F.; Höhner, D.; Wirtz, S.; Scherer, V.; Ley, U.; Behr, H.M. DEM/CFD Modeling of the Fuel Conversion in a Pellet Stove. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 152, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga, J.F.; Aguado, R.; Atxutegi, A.; Bilbao, J.; Olazar, M. Kinetic Modelling of Pine Sawdust Combustion in a Conical Spouted Bed Reactor. Fuel 2018, 227, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, S.; Che, H.; Zhao, G.; Wu, J. Experiments and Numerical Simulation of Sawdust Gasification in an Air Cyclone Gasifier. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 213, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle Mendoza, I.J.; Gorritty Portillo, M.A.; Ruiz Mayta, J.G.; Alanoca Limachi, J.L.; Torretta, V.; Ferronato, N. Social Acceptance, Emissions Analysis and Potential Applications of Paper-Waste Briquettes in Andean Areas. Environ. Res. 2024, 241, 117609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, K.; Sermyagina, E.; Saari, J.; Lahti, J.; Vakkilainen, E.; Mänttäri, M.; Kallioinen-Mänttäri, M. Techno-Economic Assessment of Hemicellulose Extraction of Softwood Sawdust Coupled with Pelletising. Energy 2025, 319, 134886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, V.; Temporim, R.B.L.; Paglianti, A.; Di Giuseppe, A.; Cotana, F.; Nicolini, A. Energy and Environmental Valorisation of Residual Wood Pellet by Small Size Residential Heating Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, P.; Tabil, L.G.; Adapa, P.K.; Cree, D.; Mupondwa, E.; Emadi, B. Torrefaction and Densification of Wood Sawdust for Bioenergy Applications. Fuels 2022, 3, 152–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dernbecher, A.; Dieguez-Alonso, A.; Ortwein, A.; Tabet, F. Review on Modelling Approaches Based on Computational Fluid Dynamics for Biomass Combustion Systems. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2019, 9, 129–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinis, A.; Kurkela, E.; Kurkela, M.; Habermeyer, F.; Lekavičius, V.; Striūgas, N.; Skvorčinskienė, R.; Neniškis, E.; Tarvydas, D. Economic Attractiveness of the Flexible Combined Biofuel Technology in the District Heating System. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Máximo, M.; García, C.A.; Pintor-Ibarra, L.F.; Alvarado-Flores, J.J.; Velázquez-Martí, B.; Rutiaga-Quiñones, J.G. Evaluation and Characterization of Timber Residues of Pinus Spp. as an Energy Resource for the Production of Solid Biofuels in an Indigenous Community in Mexico. Forests 2021, 12, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobniak, A.; Jelonek, Z.; Widziewicz-Rzońca, K.; Mastalerz, M.; Schimmelmann, A.; Jelonek, I. The Impact of Domestic Combustion of Biomass Pellets on the Environment and Human Health: Example from Poland. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gageanu, I.; Cujbescu, D.; Persu, C.; Tudor, P.; Cardei, P.; Matache, M.; Vladut, V.; Biris, S.; Voicea, I.; Ungureanu, N. Influence of Input and Control Parameters on the Process of Pelleting Powdered Biomass. Energies 2021, 14, 4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koraïem, M.; Assanis, D. Wood Stove Combustion Modeling and Simulation: Technical Review and Recommendations. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 127, 105423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Farid, M.U.; Nasir, A.; Anjum, S.A.; Ciolkosz, D.E. Techno-Economic Analysis of Biomass Pelletization as a Sustainable Biofuel with Net-Zero Carbon Emissions. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 11161–11174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, E.J.; Healey, J.R.; Newman, G.; Styles, D. Circular Wood Use Can Accelerate Global Decarbonisation but Requires Cross-Sectoral Coordination. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aso, S.; Osuji, C.; Iwe, M.; Achinewhu, S. Circular Economy Use of Biomass Residues to Alleviate Poverty, Environment, and Health Constraints. Reciklaza Odrziv. Razvoj 2023, 16, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwale, W.; Frodeson, S.; Berghel, J.; Henriksson, G.; Finell, M.; Arshadi, M.; Jonsson, C. Influence on Off-Gassing during Storage of Scots Pine Wood Pellets Produced from Sawdust with Different Extractive Contents. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 156, 106325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbaş, A. Trace Metal Concentrations in Ashes from Various Types of Biomass Species. Energy Sources 2003, 25, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosen, L.M.; Sigvardsen, N.M. Heavy Metal Leaching from Wood Ash before and after Hydration and Carbonation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bożym, M.; Gendek, A.; Siemiątkowski, G.; Aniszewska, M.; Malaťák, J. Assessment of the Composition of Forest Waste in Terms of Its Further Use. Materials 2021, 14, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirski, R.; Dukarska, D.; Derkowski, A.; Czarnecki, R.; Dziurka, D. By-Products of Sawmill Industry as Raw Materials for Manufacture of Chip-Sawdust Boards. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severo, L.S.; Rodrigues, J.B.; Campanelli, D.A.; Pereira, V.M.; Menezes, J.W.; de Menezes, E.W.; Valsecchi, C.; Vasconcellos, M.A.Z.; Armas, L.E.G. Synthesis and Raman Characterization of Wood Sawdust Ash, and Wood Sawdust Ash-Derived Graphene. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 117, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meko, B.; Ighalo, J.O. Utilization of Cordia Africana Wood Sawdust Ash as Partial Cement Replacement in C 25 Concrete. Clean. Mater. 2021, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, J.R.; Islam, M.S. Characteristics of Compressed Stabilized Earth Block Fabricated with Sawdust Ash Based Geopolymer. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 101, 111840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, R.; Burhan, H.; Bekmezci, M.; Isgin, E.S.; Akin, M.; Sen, F. Synthesis and Characterization of Lignin-Based Carbon Nanofiber Supported Platinum–Ruthenium Nanoparticles Obtained from Wood Sawdust and Applications in Alcohol Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, 48, 21128–21138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Xu, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Du, H.; Hu, J.; Liu, K.; Si, C. Simultaneous Preparation of Lignin-Containing Cellulose Nanocrystals and Lignin Nanoparticles from Wood Sawdust by Mixed Organic Acid Hydrolysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppsson, K.-H.; Magnusson, M.; Bergström Nilsson, S.; Ekman, L.; Winblad von Walter, L.; Jansson, L.-E.; Landin, H.; Rosander, A.; Bergsten, C. Comparisons of Recycled Manure Solids and Wood Shavings/Sawdust as Bedding Material—Implications for Animal Welfare, Herd Health, Milk Quality, and Bedding Costs in Swedish Dairy Herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 5779–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charis, G.; Patel, B. Operating Regimes for Intra-Carbonisation of Sawdust with Low External Fuel Requirements. Energy Nexus 2025, 18, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, J.; Martinsson, F.; Gustavsson, M. Greenhouse Gas Performance of Heat and Electricity from Wood Pellet Value Chains—Based on Pellets for the Swedish Market. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2015, 9, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgarbossa, A.; Boschiero, M.; Pierobon, F.; Cavalli, R.; Zanetti, M. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Bioenergy Production from Different Wood Pellet Supply Chains. Forests 2020, 11, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaghiani, S.; Mafakheri, F.; Chen, Z. Life Cycle Assessment of Bioenergy Production Using Wood Pellets: A Case Study of Remote Communities in Canada. Energies 2023, 16, 5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topić Božič, J.; Fric, U.; Čikić, A.; Muhič, S. Life Cycle Assessment of Using Firewood and Wood Pellets in Slovenia as Two Primary Wood-Based Heating Systems and Their Environmental Impact. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udokpoh, U.U.; Nnaji, C.C. Reuse of Sawdust in Developing Countries in the Light of Sustainable Development Goals. Recent Prog. Mater. 2023, 5, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Reveles, M.A.; Ruiz-García, V.M.; Ramos-Vargas, S.; Vargas-Larreta, B.; Masera, O.; Heya, M.N.; Carrillo-Parra, A. Assessment of Pellets from Three Forest Species: From Raw Material to End Use. Forests 2021, 12, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Included | Excluded |

|---|---|

| Energy | Physics and Astronomy |

| Environmental Science | Social Sciences |

| Chemical Engineering | Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology |

| Engineering | Medicine |

| Agricultural and Biological Sciences | Earth and Planetary Sciences |

| Materials Science | Immunology and Microbiology |

| Chemistry | Veterinary |

| Mathematics | Dentistry |

| Computer Science | Neuroscience |

| Business, Management and Accounting | Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics |

| Multidisciplinary | Health Professions |

| Economics, Econometrics and Finance |

| CAME Element | Analysis |

|---|---|

| Correct | Raw Material Variability, Presence of Contaminants and Need for Treatment, Optimisation of pelletising parameters, Improvements and development on multiphase phenomena simulation |

| Adapt | Strategies to monitor and control contaminants in raw materials and ash, Pellet handling processes, Investigate innovative options for ash valorisation, Supply chain development models that can handle raw material variability |

| Maintain | Availability and low cost of sawdust, Quantification of environmental benefits, Promote the pellet format benefits, Optimise current applications |

| Explore | Position sawdust pellet as a key energetic solution, diversifying the energy mix., New business models for sawdust pellets, Sawdust integration into the circular economy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Flores, A.; Gutiérrez-Paredes, G.J.; Merchán-Cruz, E.A.; Zacarías, A.; Flores-Herrera, L.A.; Sandoval-Pineda, J.M. Review of Wood Sawdust Pellet Biofuel: Preliminary SWOT and CAME Analysis. Processes 2025, 13, 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113607

García-Flores A, Gutiérrez-Paredes GJ, Merchán-Cruz EA, Zacarías A, Flores-Herrera LA, Sandoval-Pineda JM. Review of Wood Sawdust Pellet Biofuel: Preliminary SWOT and CAME Analysis. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113607

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Flores, Artemio, Guadalupe Juliana Gutiérrez-Paredes, Emmanuel Alejandro Merchán-Cruz, Alejandro Zacarías, Luis Armando Flores-Herrera, and Juan Manuel Sandoval-Pineda. 2025. "Review of Wood Sawdust Pellet Biofuel: Preliminary SWOT and CAME Analysis" Processes 13, no. 11: 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113607

APA StyleGarcía-Flores, A., Gutiérrez-Paredes, G. J., Merchán-Cruz, E. A., Zacarías, A., Flores-Herrera, L. A., & Sandoval-Pineda, J. M. (2025). Review of Wood Sawdust Pellet Biofuel: Preliminary SWOT and CAME Analysis. Processes, 13(11), 3607. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113607