A Distributed Parameter Identification Method for Tractor Electro-Hydraulic Hitch Systems Based on Dual-Mode Grey-Box Modelling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Principle and Test Platform

2.1.1. Hydraulic System Schematic

2.1.2. Test Platform

2.1.3. Data Acquisition System

2.2. Dual-Mode Grey-Box Model Architecture with Transfer Function-Neural Network Compensator

2.2.1. System Operation Mode Analysis and Decoupling

2.2.2. Development of Benchmark Transfer Function Models

- (1)

- Lifting Process

- (2)

- Lowering Process

2.2.3. Design of the LSTM-Based Neural Network Compensator

Design of the LSTM-Based Neural Network Compensator

Input Sequence Construction and Network Mapping

2.2.4. Integration of the Dual-Mode Grey-Box Model

2.3. Experimental Design

2.3.1. Static Characteristic Testing

2.3.2. Dynamic Characteristic Testing

2.3.3. Dataset Construction and Division

- (1)

- Baseline Transfer Function Model: The identification process was optimized using all 16 dynamic test datasets (totaling 16 × 1001 = 16,016 sample points) to determine the optimal parameter that minimizes the overall root mean square error between the output of the benchmark transfer function model and the actual system output across the entire dataset.

- (2)

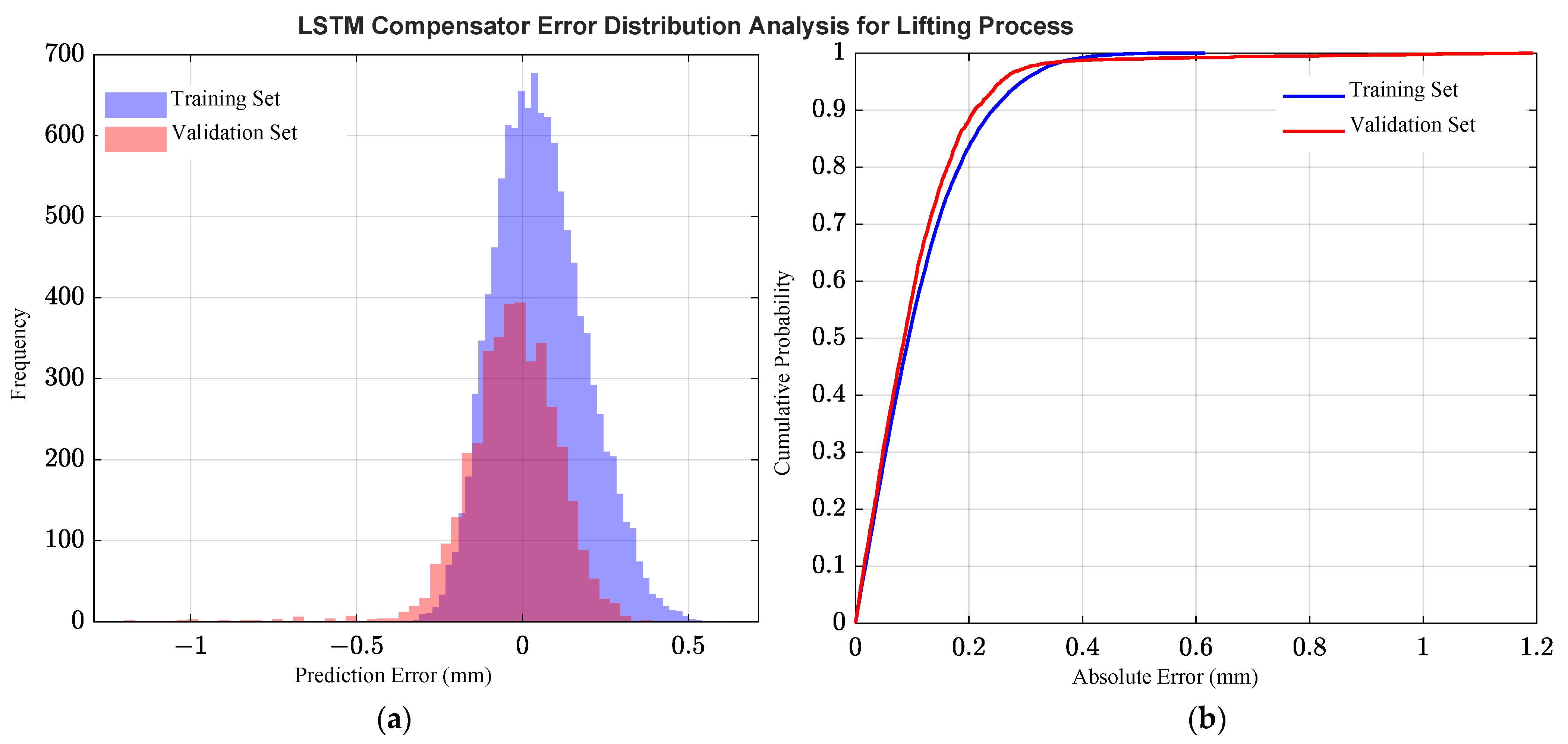

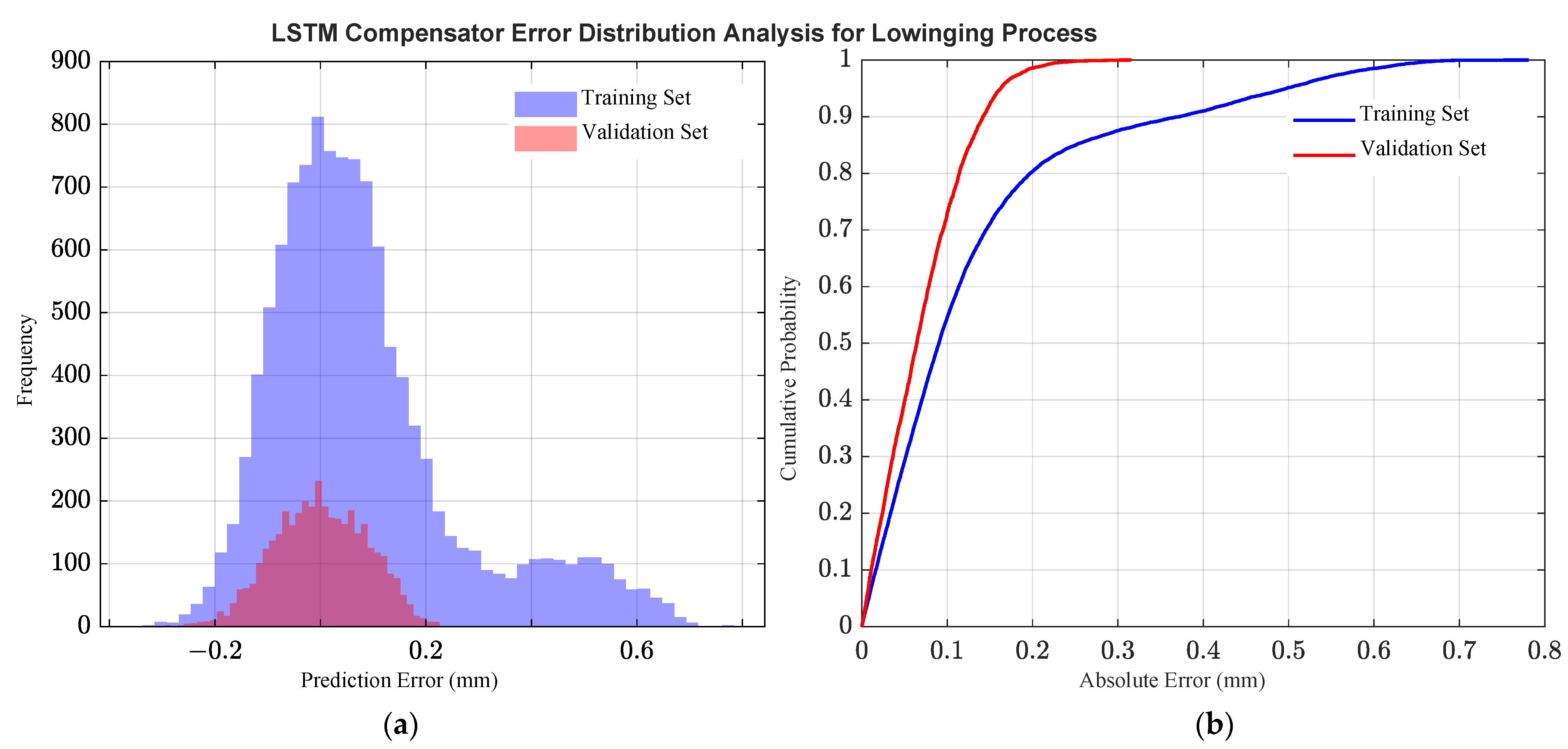

- LSTM Neural Network Compensator: After obtaining the optimal parameter for the benchmark transfer function model, the 16 datasets were further divided into 12 training sets and 4 validation sets. As described in Section 2.2.3, the input sequences for the LSTM were generated using a sliding window method with a window length of . The first 50 samples of each dataset served as historical data, resulting in a total of training samples for updating the network weights during training. Similarly, validation samples were generated from the validation set to monitor the training process, prevent overfitting, and determine the optimal LSTM parameter .

2.4. Distributed Parameter Identification Strategy Using WOA and LSTM

2.4.1. Parameter Definition and Objective Function

2.4.2. Distributed Identification Procedure

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Identification Results

3.1.1. Transfer Function Parameter Identification

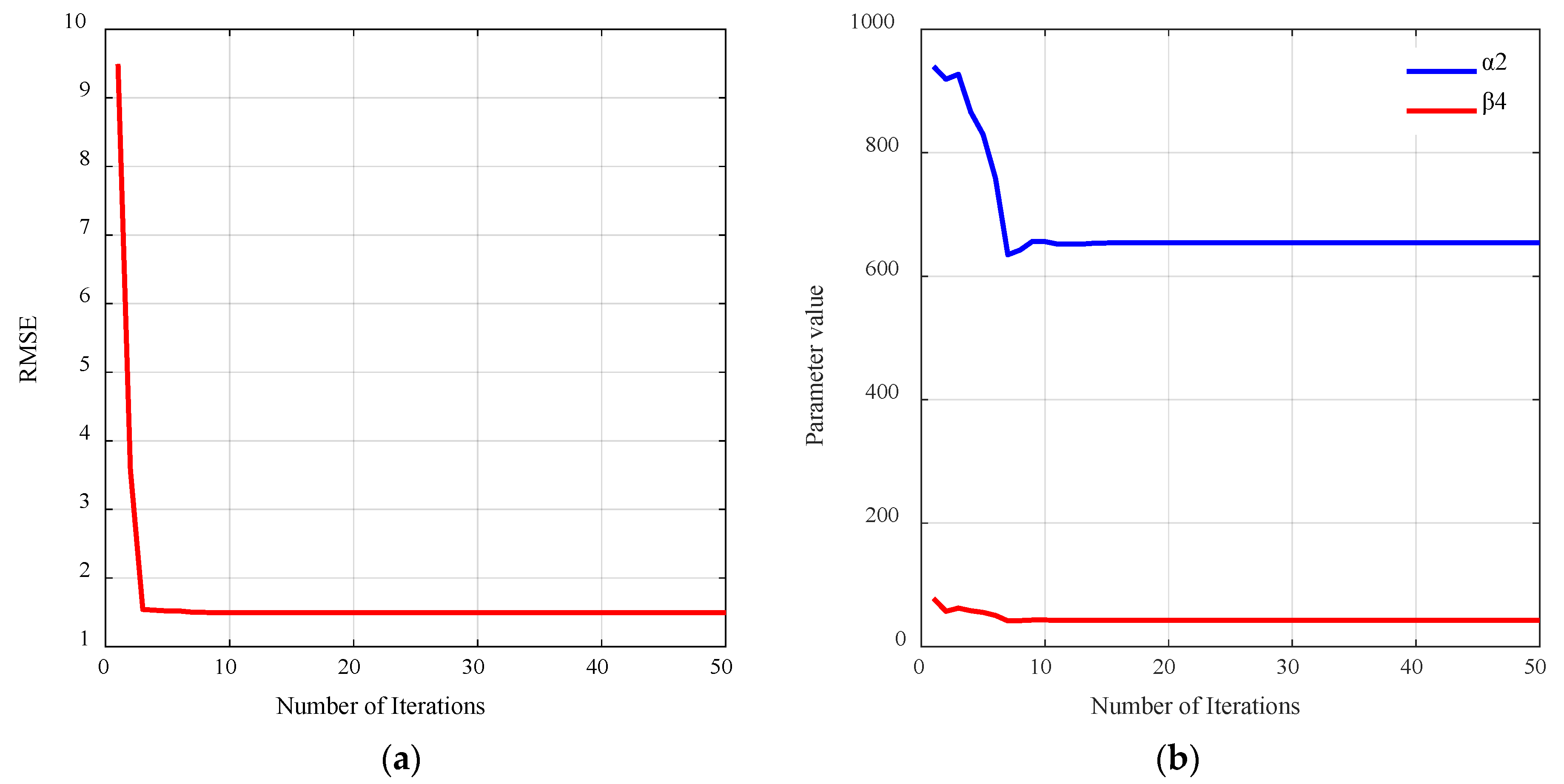

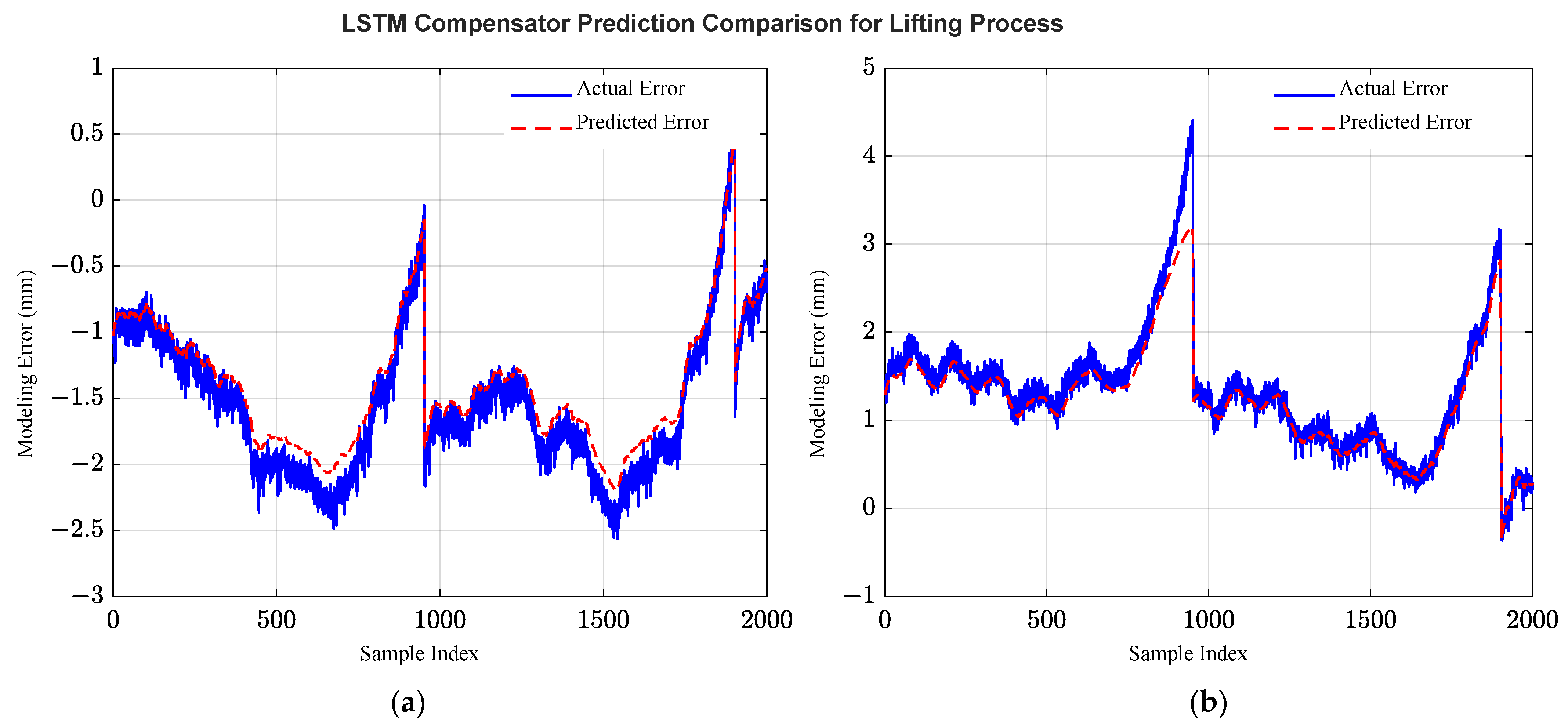

3.1.2. LSTM Neural Network Compensator Training

3.2. Model Performance Validation

3.2.1. Validation for the Lifting Process

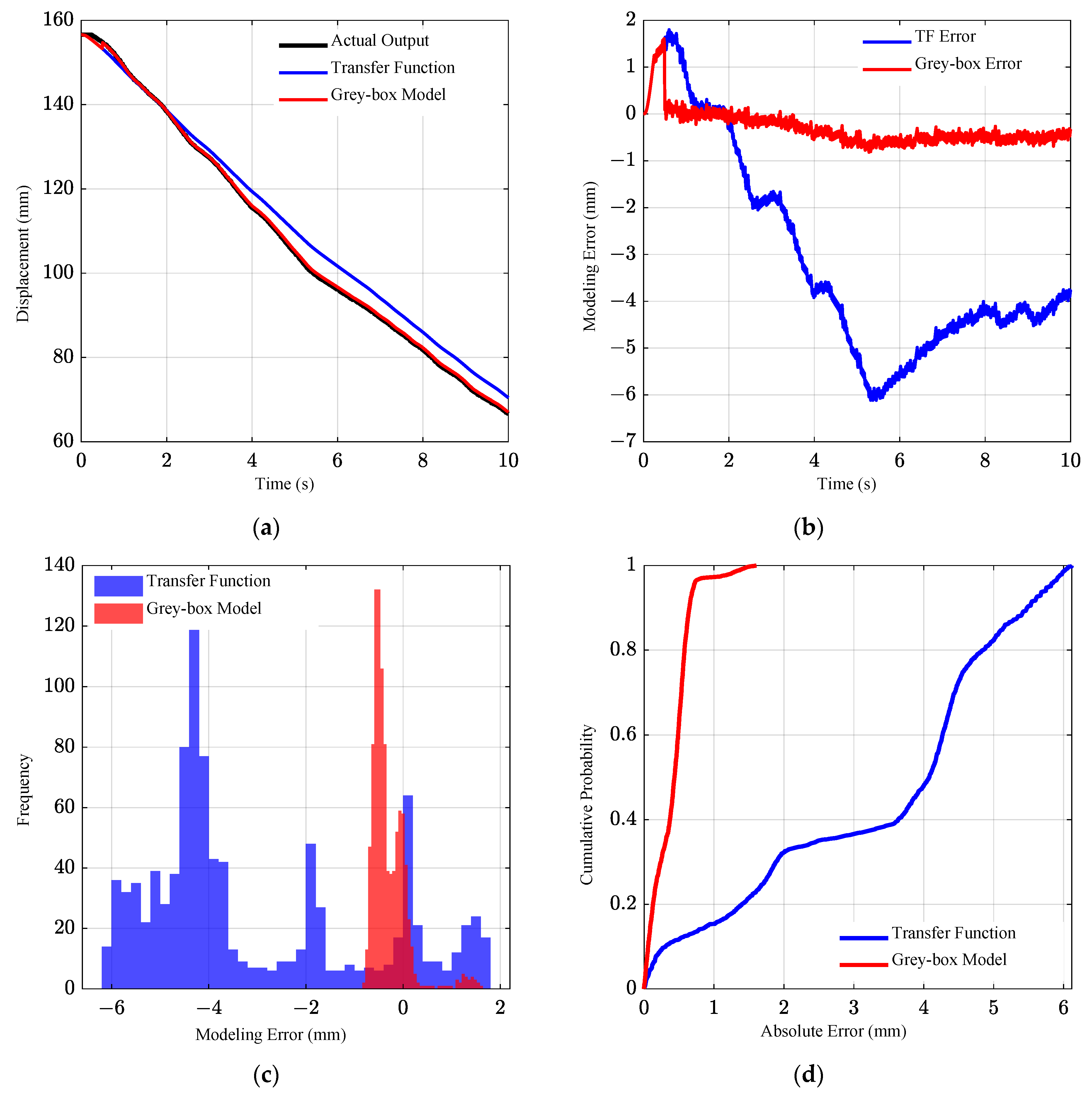

3.2.2. Validation for the Lowering Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on the mode decomposition strategy, the lifting and lowering processes of the electro-hydraulic hitch system were constructed into two subsystems, respectively, and the corresponding transfer function models were established. In order to improve the model’s ability to describe nonlinear systems, a LSTM neural network compensator is introduced to compensate the benchmark model, and a system grey-box model with both mechanism basis and high-precision characteristics was obtained, which effectively solves the problem that the dual-mode dynamic characteristics of the system are difficult to model uniformly.

- (2)

- Aiming at the high-dimensional and heterogeneous mixed parameter set in the established grey-box model, a distributed parameter identification strategy based on WOA and GD method was proposed to solve two complex joint optimization problems in a distributed manner, which effectively realizes the accurate identification of system model parameters.

- (3)

- The proposed grey-box model was verified by experiments. The results show that the RMSE of the model in the process of lifting and lowering were 0.33 mm and 0.48 mm, respectively, and the MAE were 0.24 mm and 0.40 mm, respectively. Compared with the single transfer function model, the accuracy of the model is significantly improved. This method can effectively improve the modelling accuracy of the system. It not only lays a reliable foundation for designing a high-performance controller for the tractor electro-hydraulic hitch system, but also provides a new paradigm for modelling a class of electro-mechanical–hydraulic systems with strong asymmetric and nonlinear dynamic characteristics.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wang, R.; Dong, Z. A review of green agriculture and energy management strategies for hybrid tractors. Energies 2025, 18, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Dai, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. Review of electro-hydraulic hitch system control method of automated tractors. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiero, D.; Garcia, A.P.; Umezu, C.K.; Leme, R. Swarm robots in mechanized agricultural operations: A review about challenges for research. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 193, 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunusi, I.I.; Wang, Z.Z.; Sun, C. Intelligent tractors: Review of online traction control process. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, K.R.; Raja, P.; Perez-Ruiz, M. Task-based agricultural mobile robots in arable farming: A review. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 15, e02R01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Wang, J.H.; Huang, H.L.; He, J.Y. Fuzzy sliding mode control with state estimation for velocity control system of hydraulic cylinder using a new hydraulic transformer. Eur. J. Control 2019, 48, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Chen, B.; Yang, X.K.; Guo, B.; Xu, W.; Ke, S.; Huang, S.H. Design and experimental study of tillage depth control system for electric rotary tiller based on LADRC. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Z.; Ji, X.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.Z.; Wei, X.H.; Zhang, S.C. Tillage depth regulation system via depth measurement feedback and composite sliding mode control: A field comparison validation study. Meas. Control 2023, 57, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Tewari, V.K.; Bharti, C.K.; Ranjan, A. Modeling, simulation and experimental validation of flow rate of electro-hydraulic hitch control valve of agricultural tractor. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2021, 82, 102070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Sultan, I.; Phung, T.; Kumar, A. A literature review of the design, modeling, optimization, and control of electro-mechanical inlet valves for gas expanders. Energies 2024, 17, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.B.; Na, H.C.; Kim, Y.B. Robust MPC-PIC force control for an electro-hydraulic servo system with pure compressive elastic load. Control Eng. Pract. 2018, 79, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Su, X.Y. An adaptive sliding mode controller for electro-hydraulic servo systems combining offline training and online estimation. Asian J. Control. 2024, 26, 1204–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.G.; Chen, G.X.; Yan, G.S.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Ai, C. Research on the nonlinear characteristic of flow in the electro-hydraulic servo pump control system. Processes 2021, 9, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.L.; Liu, Q.T.; Ji, H.; Hong, R.D.; Ma, Z.H. Prediction of degradation trend of water hydraulic high speed on/off valve based on machine learning. Chin. Hydraul. Pneum. 2022, 46, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.H.; Li, Z.Q.; Wang, P.F.; Liu, M.; Zhao, C.Y. Fault diagnosis of aircraft landing gear hydraulic system based on TSFFCNN-PSO-SVM. Chin. Hydraul. Pneum. 2024, 39, 20220111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aela, A.M.A.; Jean-Pierre, K.; Mintsa, H. Adaptive neural network and nonlinear electrohydraulic active suspension control system. J. Vib. Control 2022, 28, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregov, G. Modeling and predictive analysis of the hydraulic geroler motor based on artificial neural network. Eng. Rev. 2022, 42, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülker, H. Design and application of an artificial neural network controller imitating a multiple model predictive controller for stroke control of hydrostatic transmission. Machines 2025, 13, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidin, A.; Youssef, R.; Ei-hamied, R. Mathematical models for predicating draft forces of tillage tools: A review. J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2021, 26, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleko, A.T.; Kamsu, B.; Ngouna, R.H.; Tongne, A. Health condition monitoring of a complex hydraulic system using deep neural network and deepshap explainable XAI. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2023, 175, 103339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.L.; Ye, M. Application of machine learning in hydraulic fracturing: A review. ACS Omega 2025, 11, 10769–10785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, J.; Gomez, J.F.; Olivencia, F.; Crespo, A. A review of the use of artificial neural network models for energy and reliability prediction. a study of the solar PV, hydraulic and wind energy sources. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranmer, A.; Shahbakhti, M.; Hedrick, J.K. Grey-box modeling architectures for rotational dynamic control in automotive engines. In Proceedings of the 2012 American Control Conference (ACC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 27–29 June 2012; pp. 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadina, O.O.; Thaha, M.A.; Mohamed, Z.; Shaheed, M.H. Grey-box modelling and fuzzy logic control of a Leader–Follower robot manipulator system: A hybrid Grey Wolf–Whale optimisation approach. ISA Trans. 2022, 129, 572–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabacak, K. A grey-box model of a DC/DC boost converter for PV energy systems. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2024, 1, 3559456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Q.; Kuang, F.J.; Yu, S.D.; Cai, Z.N.; Chen, H.L. Static photovoltaic models’ parameter extraction using reinforcement learning strategy adapted local gradient Nelder-Mead Runge Kutta method. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 24106–24141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadianfar, I.; Bozorg, O.; Chu, X.F. Gradient-based optimizer: A new metaheuristic optimization algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2020, 540, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Streb, M.; Ko, J.Y.; Klass, V.L.; Klett, M.; Ekstrom, H.; Johansson, M.; Lindbergh, G. Parametrization of physics-based battery models from input-output data: A review of methodology and current research. J. Power Sources 2022, 521, 230859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Zhou, F.M.; Zheng, J.B. An improved parameter identification algorithm for the friction model of electro-hydraulic servo systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhao, S.Q.; Fan, Q.Q.; Zhu, X.D. A hybrid genetic algorithm-based parameter identification method for nonlinear hysteretic system with experimental verification. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2024, 24, 2450099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, D.Z.; Ni, Y.L.; Song, K.L.; Li, Y.M. Improved particle swarm optimization for parameter identification of permanent magnet synchronous motor. CMC-Comput. Mat. Contin. 2024, 79, 2187–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Zhang, W.J.; Huang, S.D. A novel parameter estimation method for PMSM by using chaotic particle swarm optimization with dynamic self-optimization. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 8424–8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, X.J. Parameters’ identification of vessel based on ant colony optimization algorithm. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6256785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, B.R.; Zhao, H.B. Data-driven rock strength parameter identification using artificial bee colony algorithm. Buildings 2022, 12, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.Z.; Cao, Z.G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.H.; Han, Y.Y.; Pan, Q.K. A review on swarm intelligence and evolutionary algorithms for solving flexible job shop scheduling problems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2019, 6, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.T.; Zeng, Y.; Qian, J.; Yang, F.J.; Xie, S.H. Parameter identification of DFIG converter control system based on WOA. Energies 2023, 16, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krainski Ferrari, A.C.; Gouvea da Silva, C.A.; Osinski, C.; Firmino Pelacini, D.A.; Leandro, G.V.; dos Santos Coelho, L. Tuning of control parameters of the whale optimization algorithm using fuzzy inference system. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 42, 3051–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; You, C.T.; Gu, Y.; Zhu, Y.F. Parameter identification of the RBF-ARX model based on the hybrid whale optimization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2024, 71, 2774–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.S.; Guo, X.W.; Zhou, M.C.; Wang, J.C.; Qin, S.J.; Qi, L. Discrete whale optimization algorithm for disassembly line balancing with carbon emission constraint. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 3055–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.Y.; Zhu, Q.J.; Wang, D.C.; Feng, Y.; Chen, X.X.; Li, Q.S. Method and validation of coal mine gas concentration prediction by integrating PSO algorithm and LSTM network. Processes 2024, 12, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.X.; Liu, H.C.; Yue, J.G.; Wu, C.H. TD-DALN: A twin data-driven design anomaly detection method for electrohydraulic actuators. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3508315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, S.J.; Wang, W.Q.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, J.M.; Tao, J.F. Response error prediction and feedback control method for electro-hydraulic actuators based on LSTM. Electronics 2025, 14, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Model | Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Displacement Sensor | PandAuto-P3036 | 0~90° | 0.3% F·s |

| Current Sensor | QD-D21 | 0~3 A | 0.3% F·s |

| Model Type | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Lifting | 6.625 | |

| 0.001 | ||

| 0.065 | ||

| 0.318 | ||

| Lowering | 654.473 | |

| 42.808 |

| Model Type | RMSE (mm) | MAE (mm) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer function | 0.79 | 0.59 | 98.81 |

| Grey-box | 0.33 | 0.24 | 99.86 |

| Model Type | RMSE (mm) | MAE (mm) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer function | 3.79 | 3.33 | 96.06 |

| Grey-box | 0.48 | 0.40 | 99.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Pan, S.; Song, Y.; Jiang, C.; Lu, Z. A Distributed Parameter Identification Method for Tractor Electro-Hydraulic Hitch Systems Based on Dual-Mode Grey-Box Modelling. Processes 2025, 13, 3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113608

Sun X, Pan S, Song Y, Jiang C, Lu Z. A Distributed Parameter Identification Method for Tractor Electro-Hydraulic Hitch Systems Based on Dual-Mode Grey-Box Modelling. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113608

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xiaoxu, Siwei Pan, Yue Song, Chunxia Jiang, and Zhixiong Lu. 2025. "A Distributed Parameter Identification Method for Tractor Electro-Hydraulic Hitch Systems Based on Dual-Mode Grey-Box Modelling" Processes 13, no. 11: 3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113608

APA StyleSun, X., Pan, S., Song, Y., Jiang, C., & Lu, Z. (2025). A Distributed Parameter Identification Method for Tractor Electro-Hydraulic Hitch Systems Based on Dual-Mode Grey-Box Modelling. Processes, 13(11), 3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113608