Mechanisms of Proppant Pack Instability and Flowback During the Entire Production Process of Deep Coalbed Methane

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical and Experimental Methods

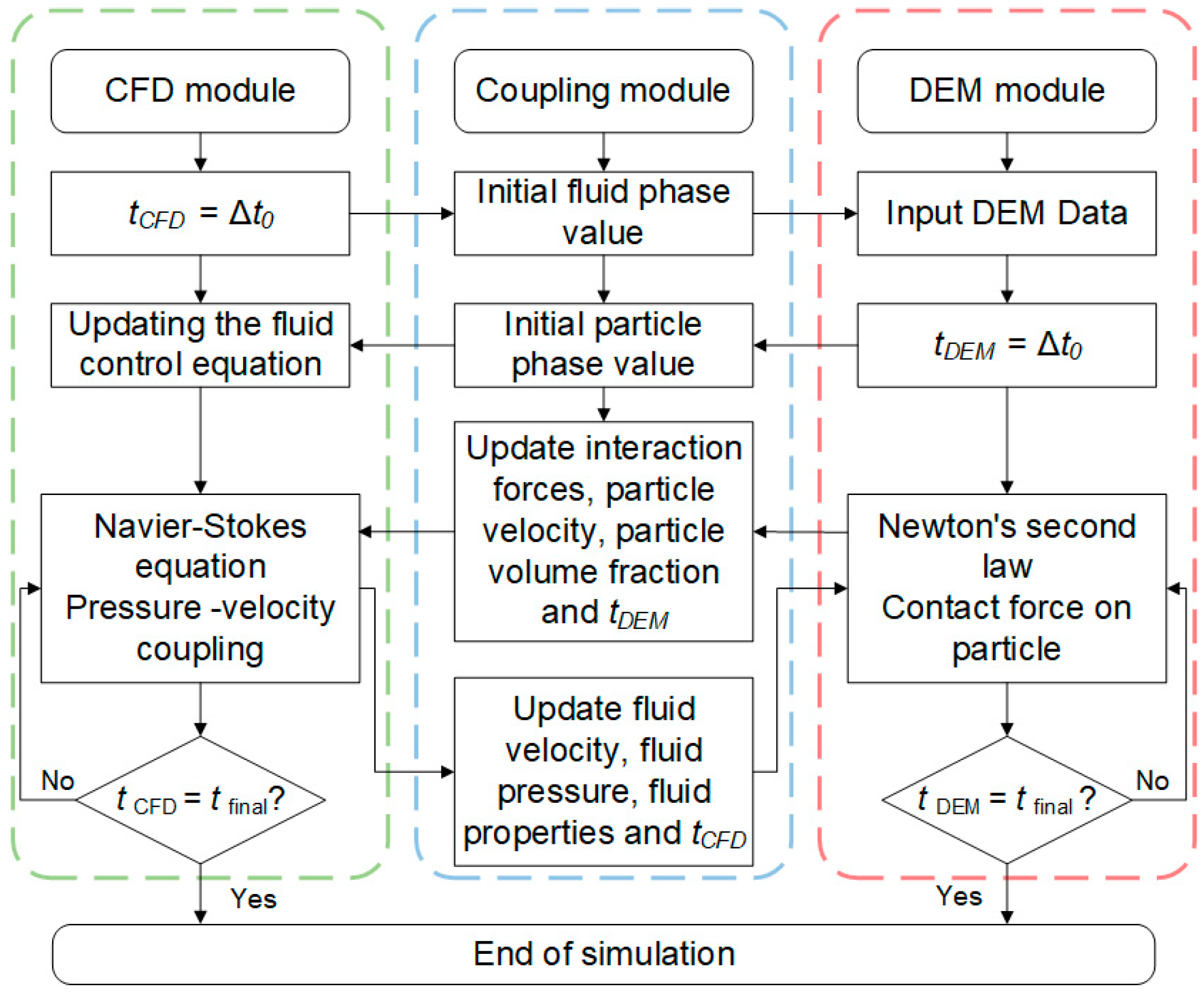

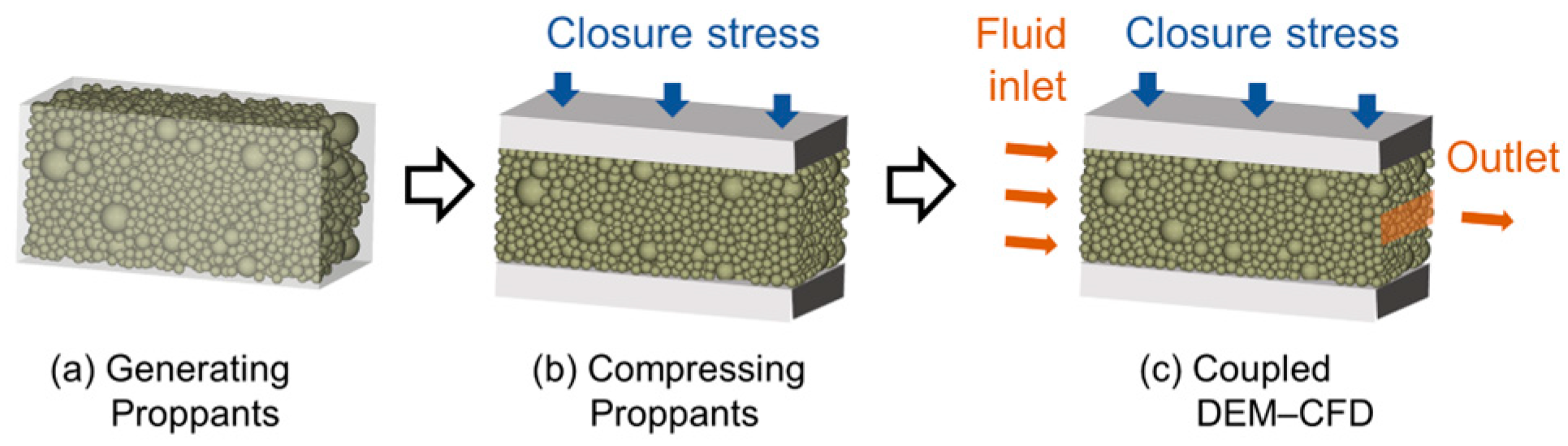

2.1. Numerical Simulation

2.1.1. Numerical Model

2.1.2. Numerical Process

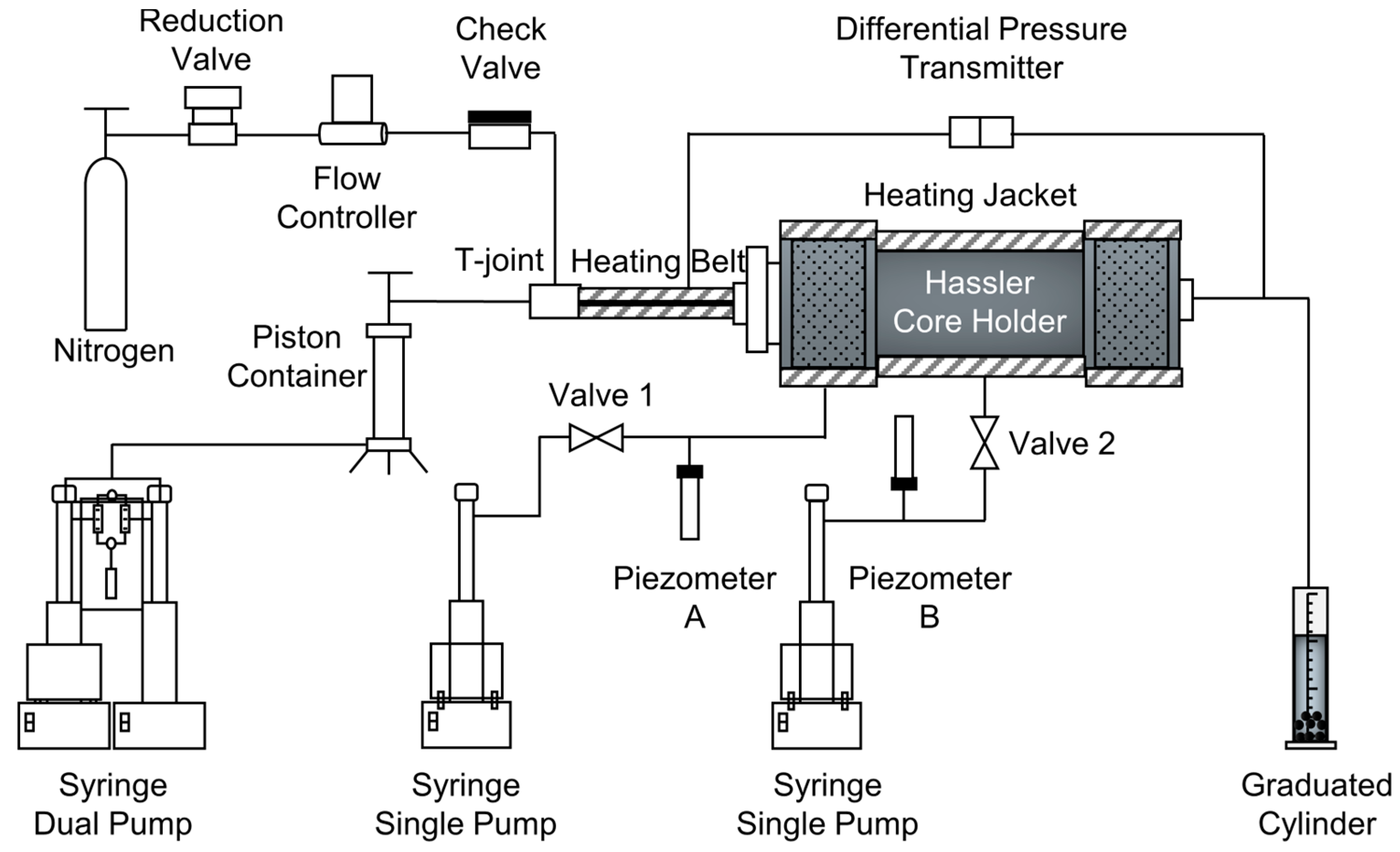

2.2. Laboratory Experiments

2.2.1. Experimental Setup

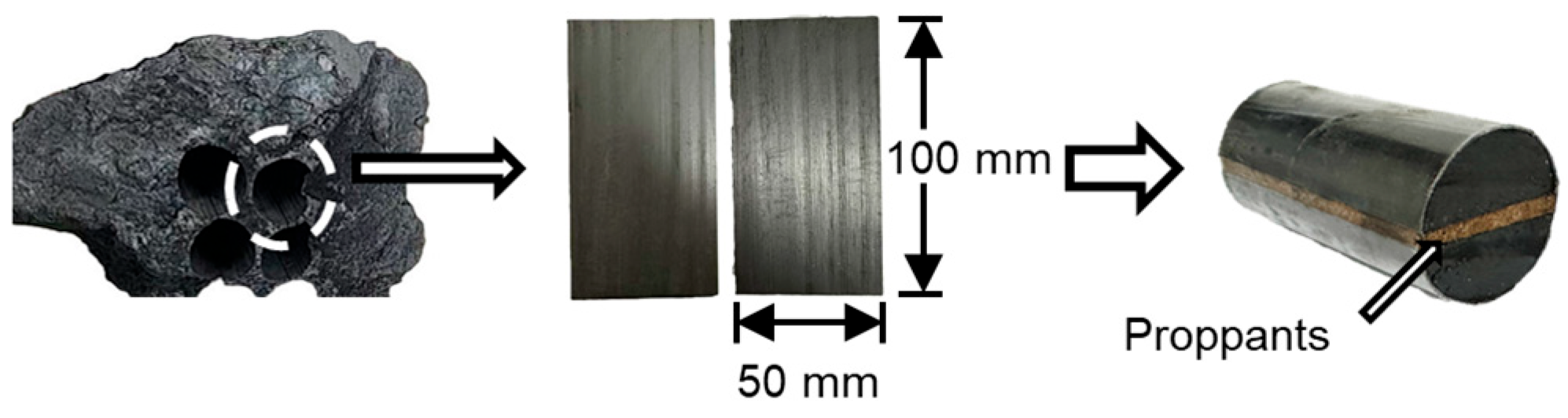

2.2.2. Experimental Materials

2.2.3. Experimental Procedure

- (a)

- Cylindrical cores (ϕ50 × 100 mm) were obtained by wire cutting and then split longitudinally into two halves. Proppants of predetermined quantities were filled between the halves to simulate fractures with varying widths. Figure 4 shows the setup, where the white circular areas indicate the openings formed on the coal block during wire cutting.

- (b)

- The proppant-packed cores were mounted in a core holder with the fracture oriented vertically. Axial and confining pressures were gradually increased to the preset values to establish the designed stress state.

- (c)

- A total of 2000 mL of 2 wt% KCl solution was prepared and loaded into the piston container.

- (d)

- The temperature was adjusted to the target value and maintained for 4 h. Outlet temperature was continuously monitored to ensure equilibrium with the set conditions.

- (e)

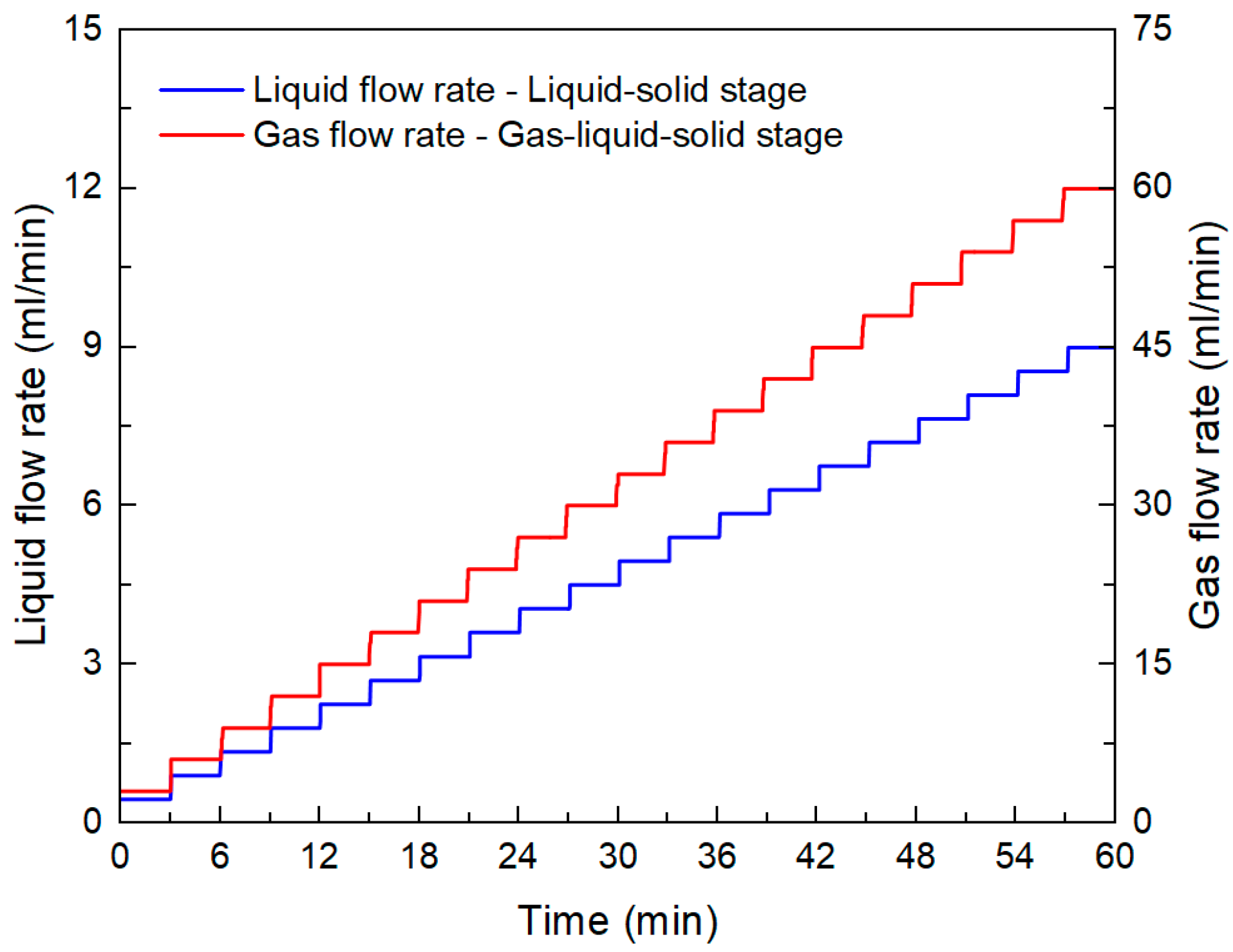

- For liquid-solid two-phase tests, liquid flow rate was adjusted to 0.45 mL/min and maintained for more than 5 min until no bubbles appeared at the outlet. For gas-liquid-solid three-phase tests, gas flow rate was adjusted to 2 mL/min and maintained for more than 5 min until no liquid was discharged at the outlet.

- (f)

- The data acquisition system was activated to monitor flow rate, pressure, and temperature. Flow rate was then increased stepwise at fixed gradients every 3 min, while graduated cylinders at the outlet were replaced to collect flowback proppants.

- (g)

- After 60 min, the experiment was terminated. The core was removed, and photographs were taken to record the morphology of the proppant pack after flowback. The returned proppants were subsequently dried and weighed.

- (h)

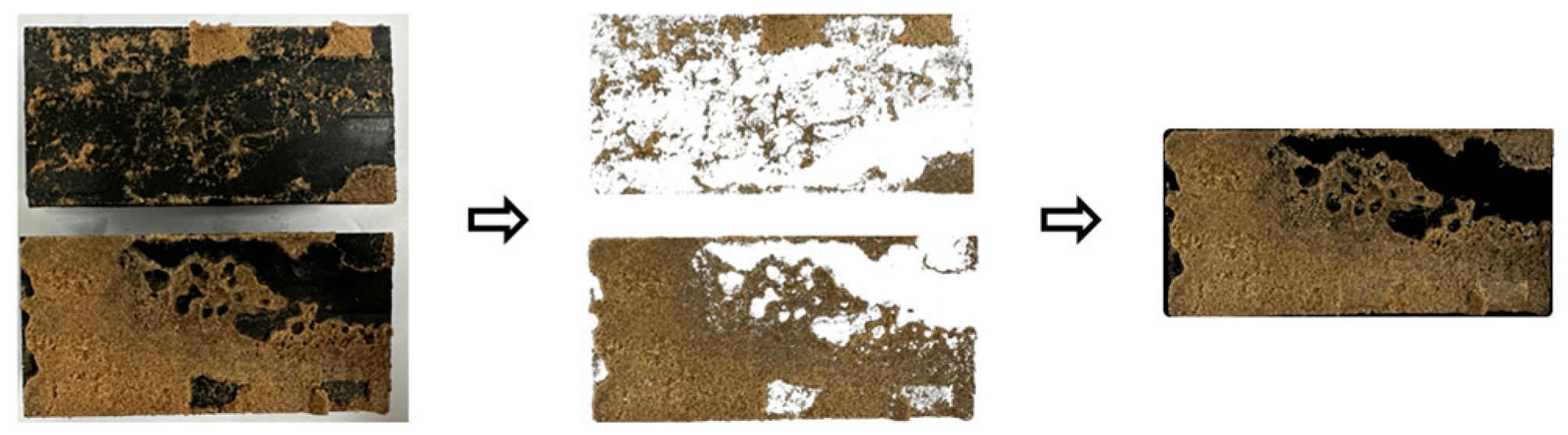

- After the experiments, some proppants were found to be embedded in or attached to both fracture surfaces. To quantify their post-flowback distribution, the acquired images were converted into the HSV color space, and a fixed threshold range for the yellow hue was applied to extract the proppant pixels. The threshold range was calibrated by extracting the HSV distribution of proppants from several reference images taken under identical illumination and camera settings, so that the selected hue interval could be statistically determined and consistently applied to all images. This procedure ensured reproducibility and minimized subjective bias in image segmentation. After thresholding, coal regions were removed by transparency processing, and the proppant masks from both sides were merged to obtain the final spatial distribution. The complete image-processing workflow is illustrated in Figure 5.

2.2.4. Flow Rate Settings

3. Results and Discussion

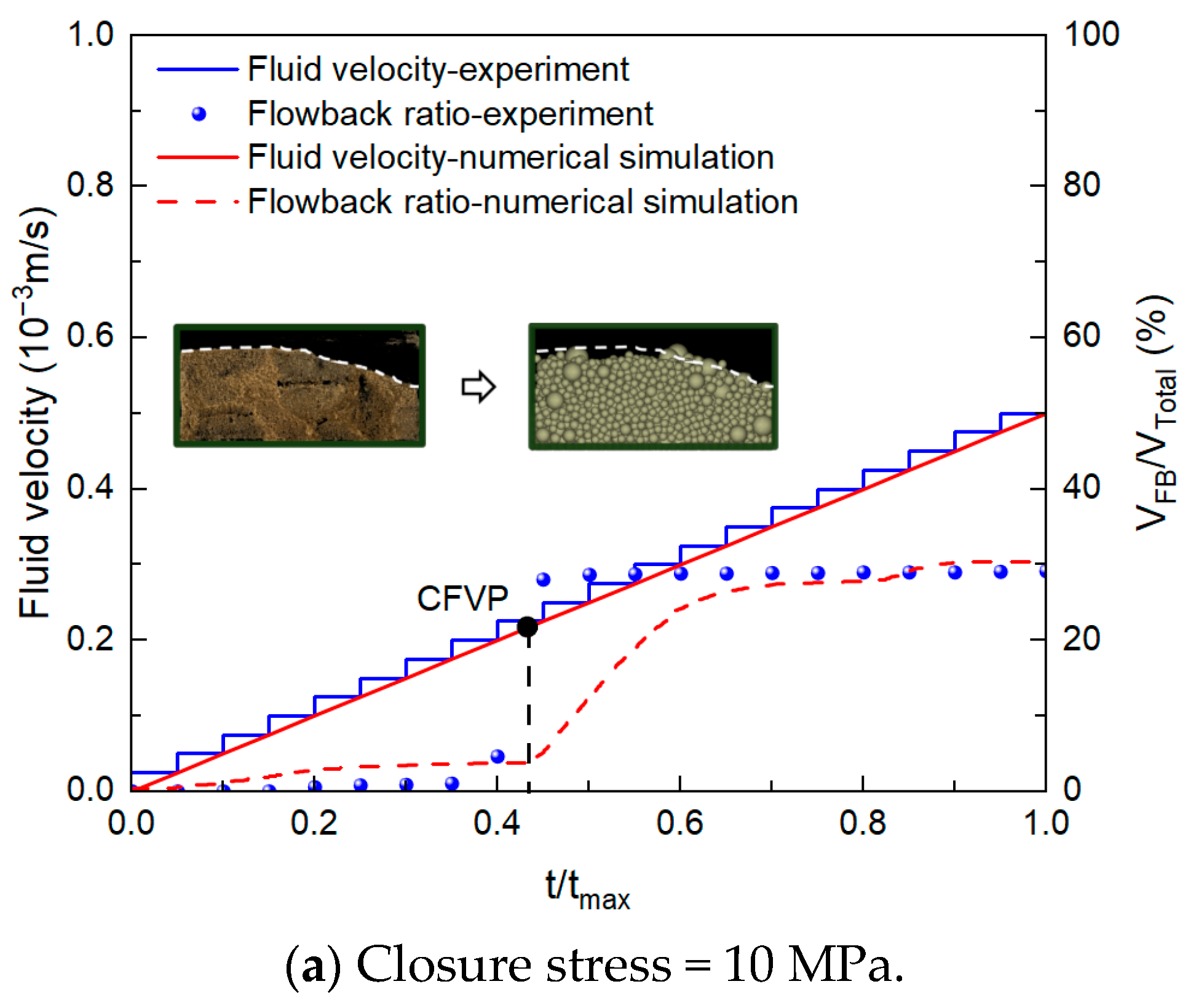

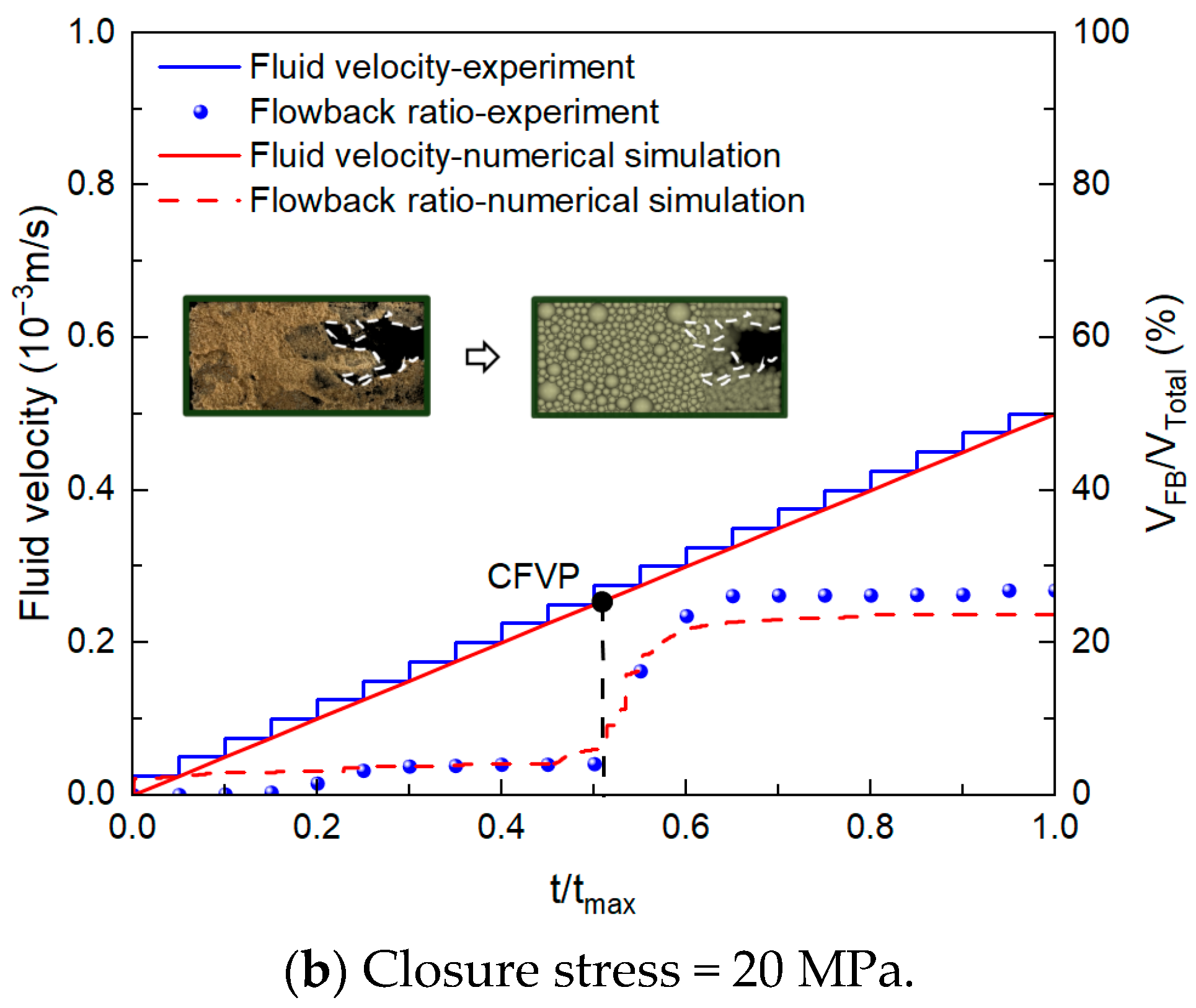

3.1. Proppant Flowback Mechanism

3.1.1. Model Validation

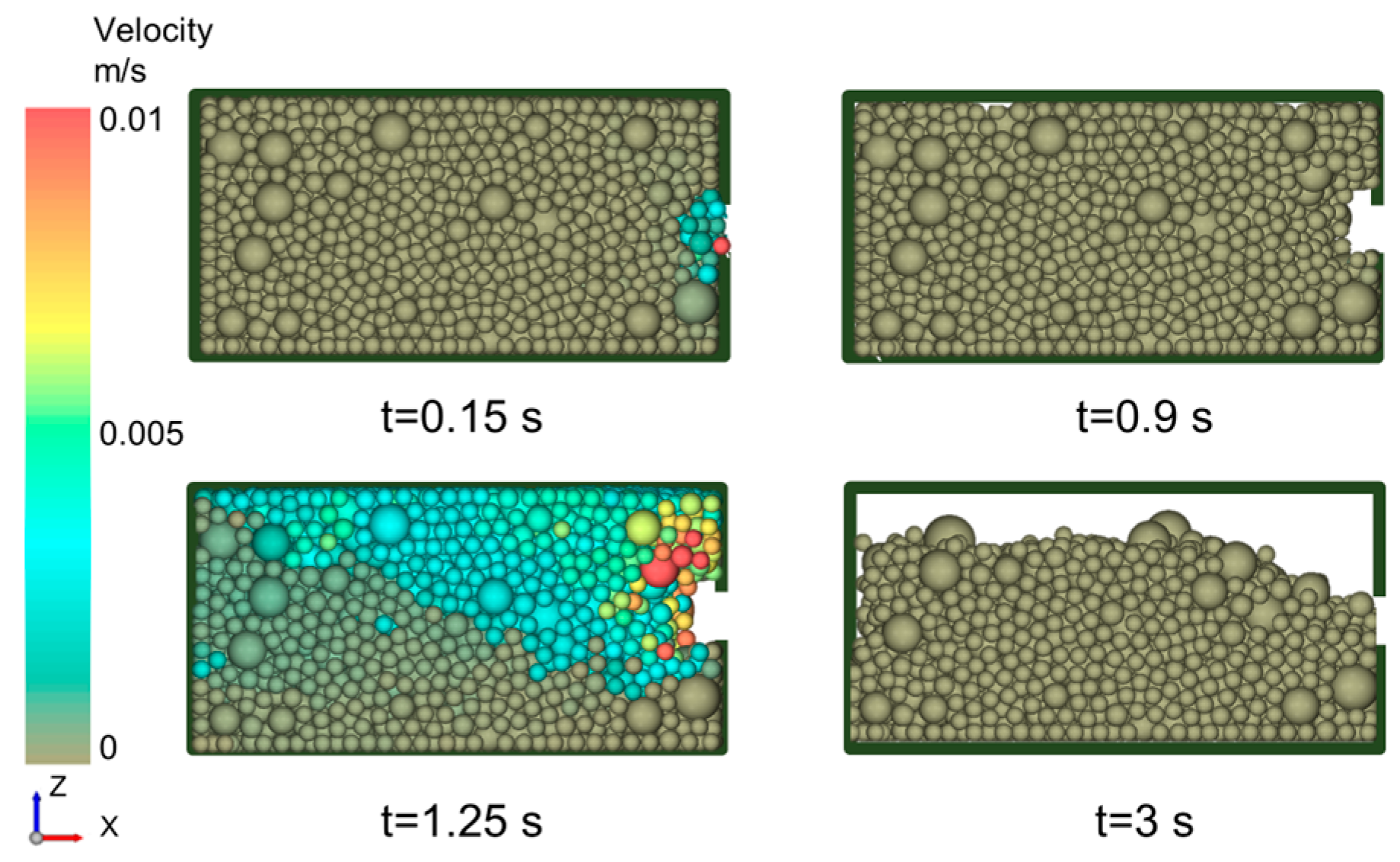

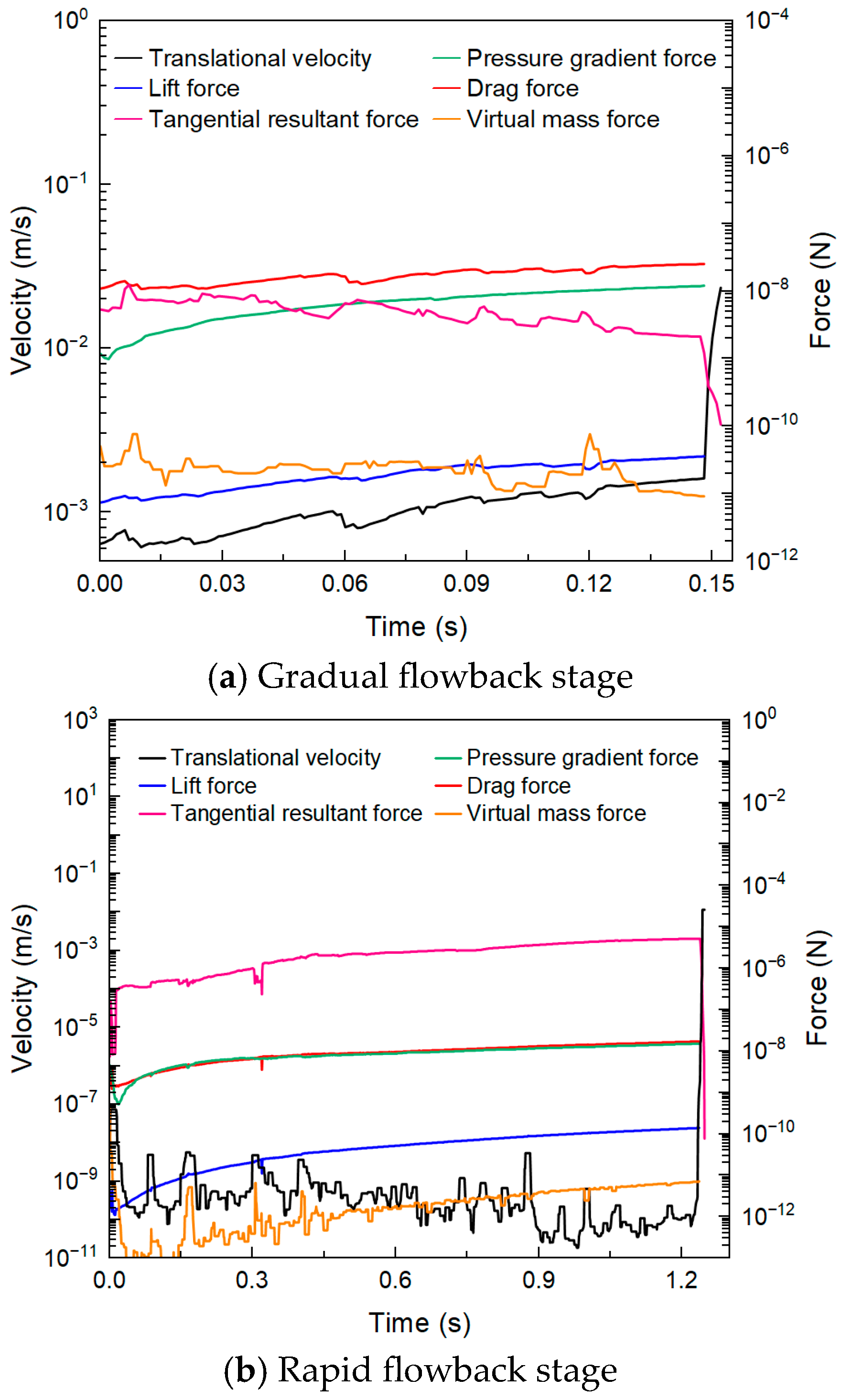

3.1.2. Process and Mechanisms of Proppant Flowback

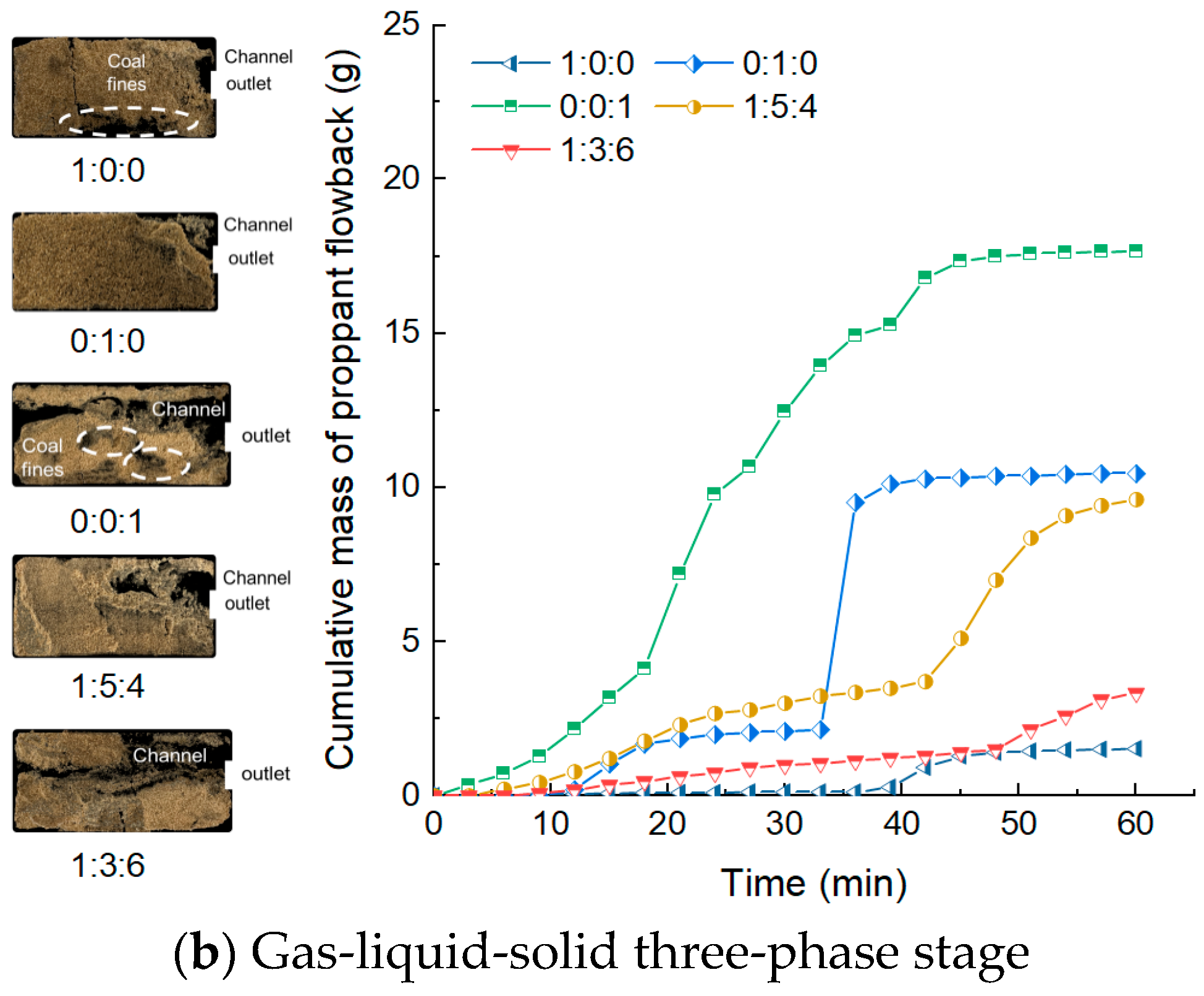

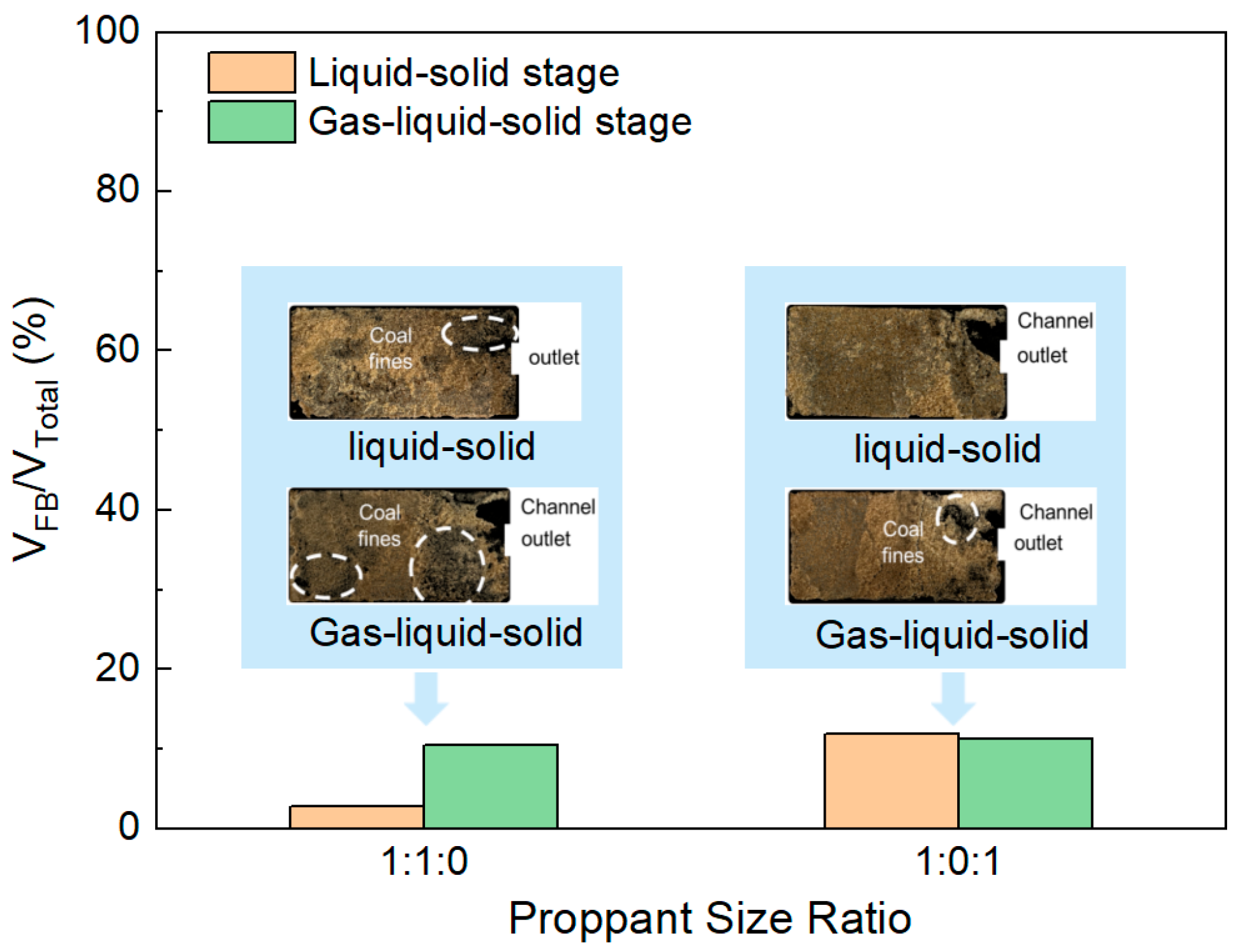

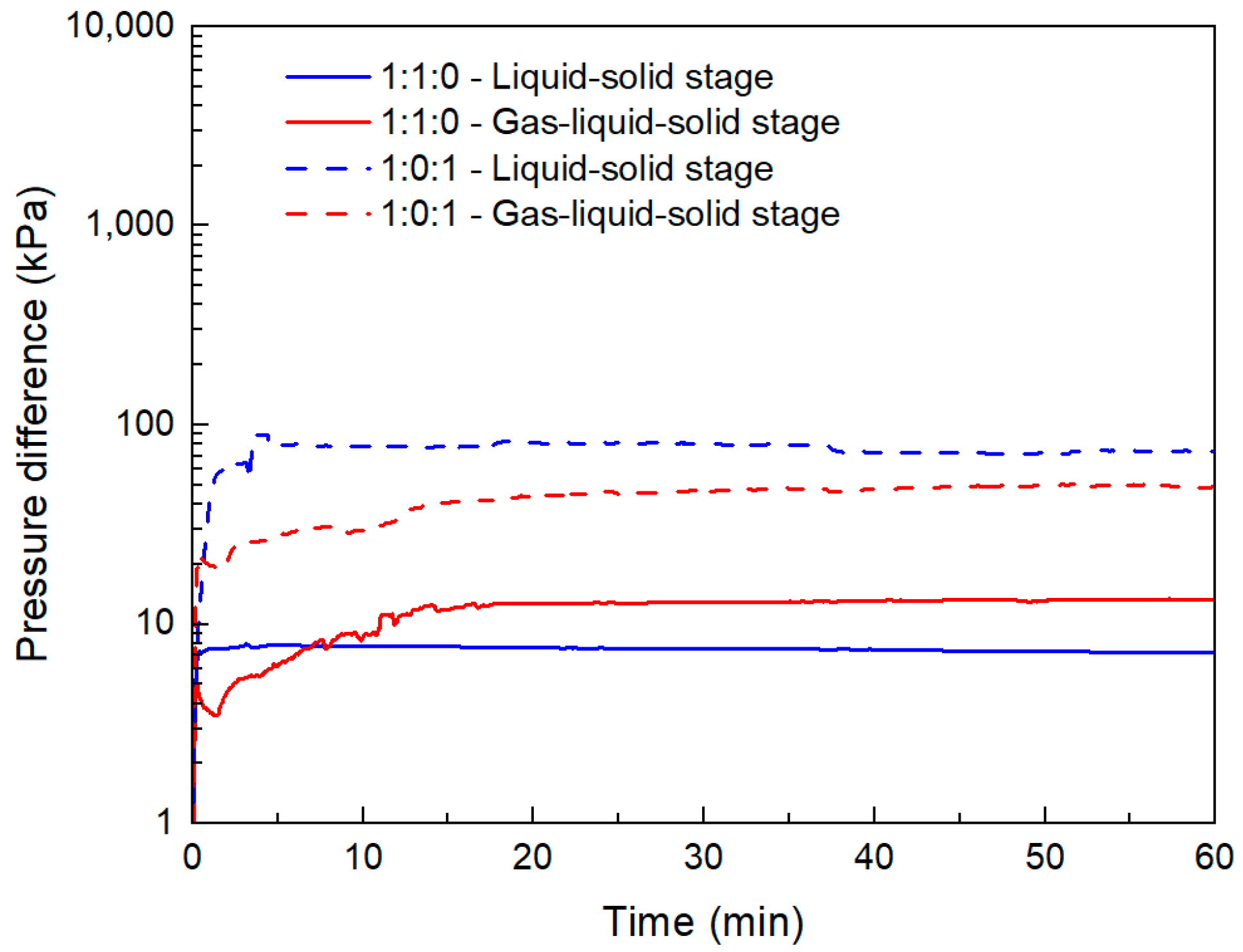

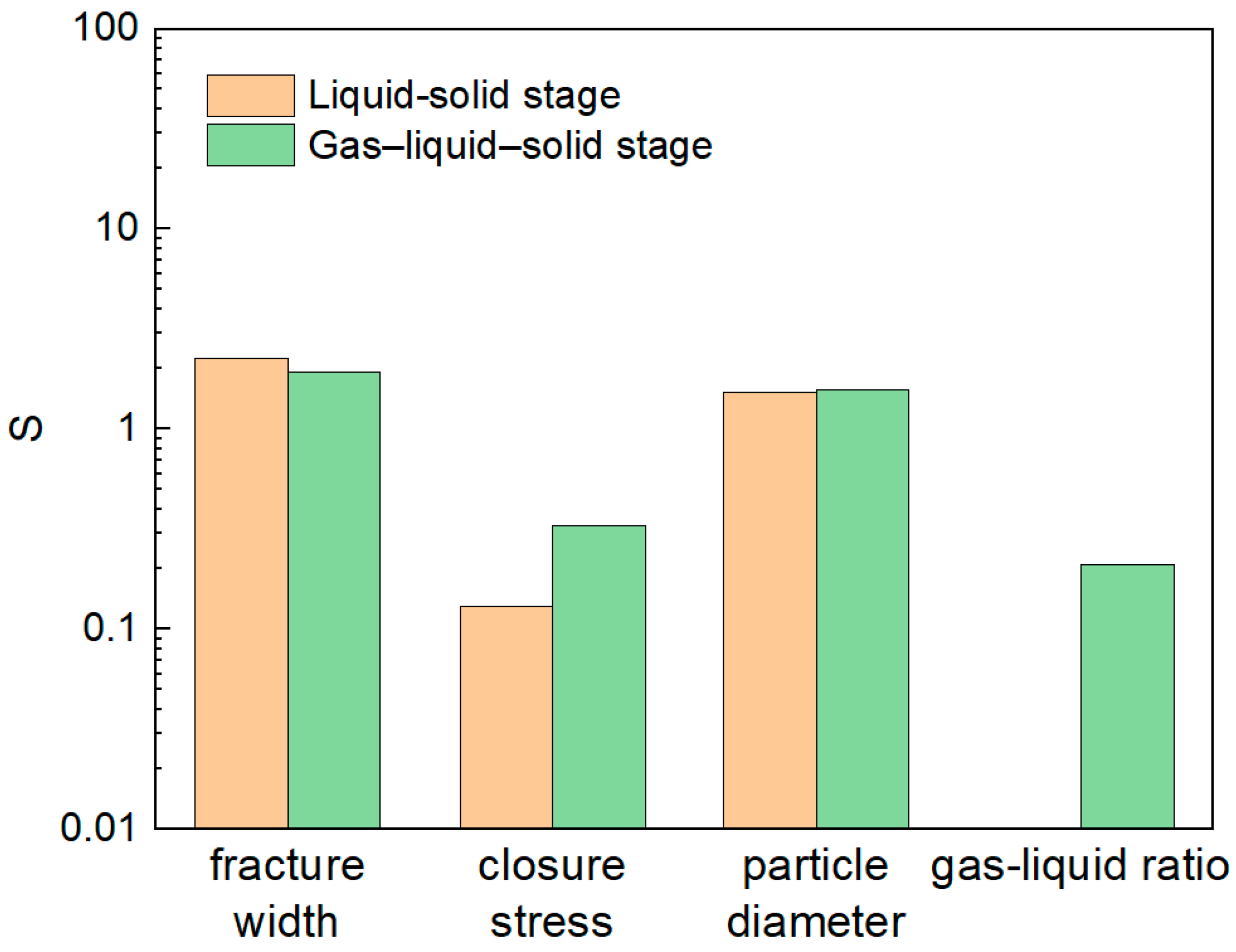

3.2. Regularities of Critical Flowback Velocity of Proppants

3.2.1. Experimental Scheme

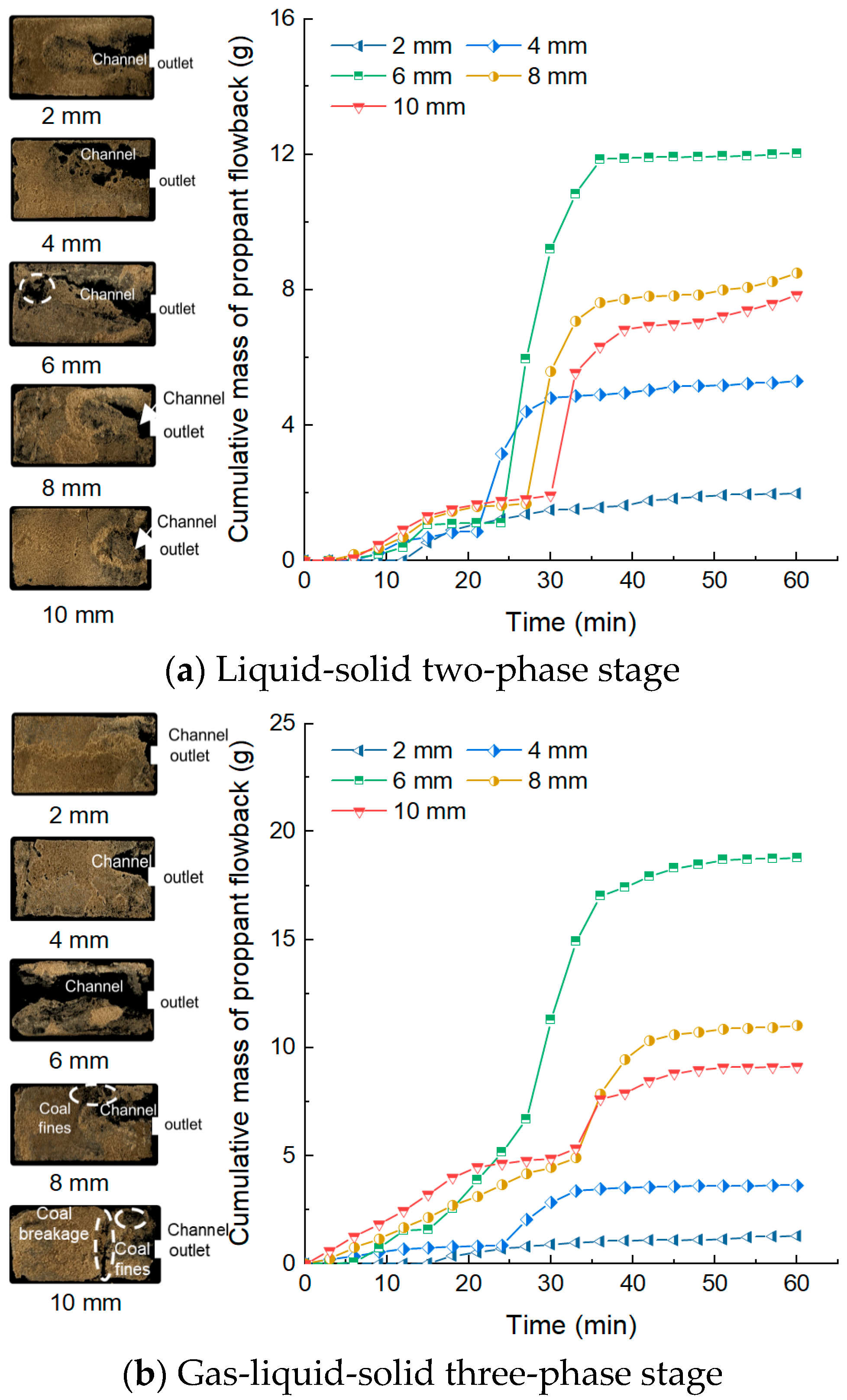

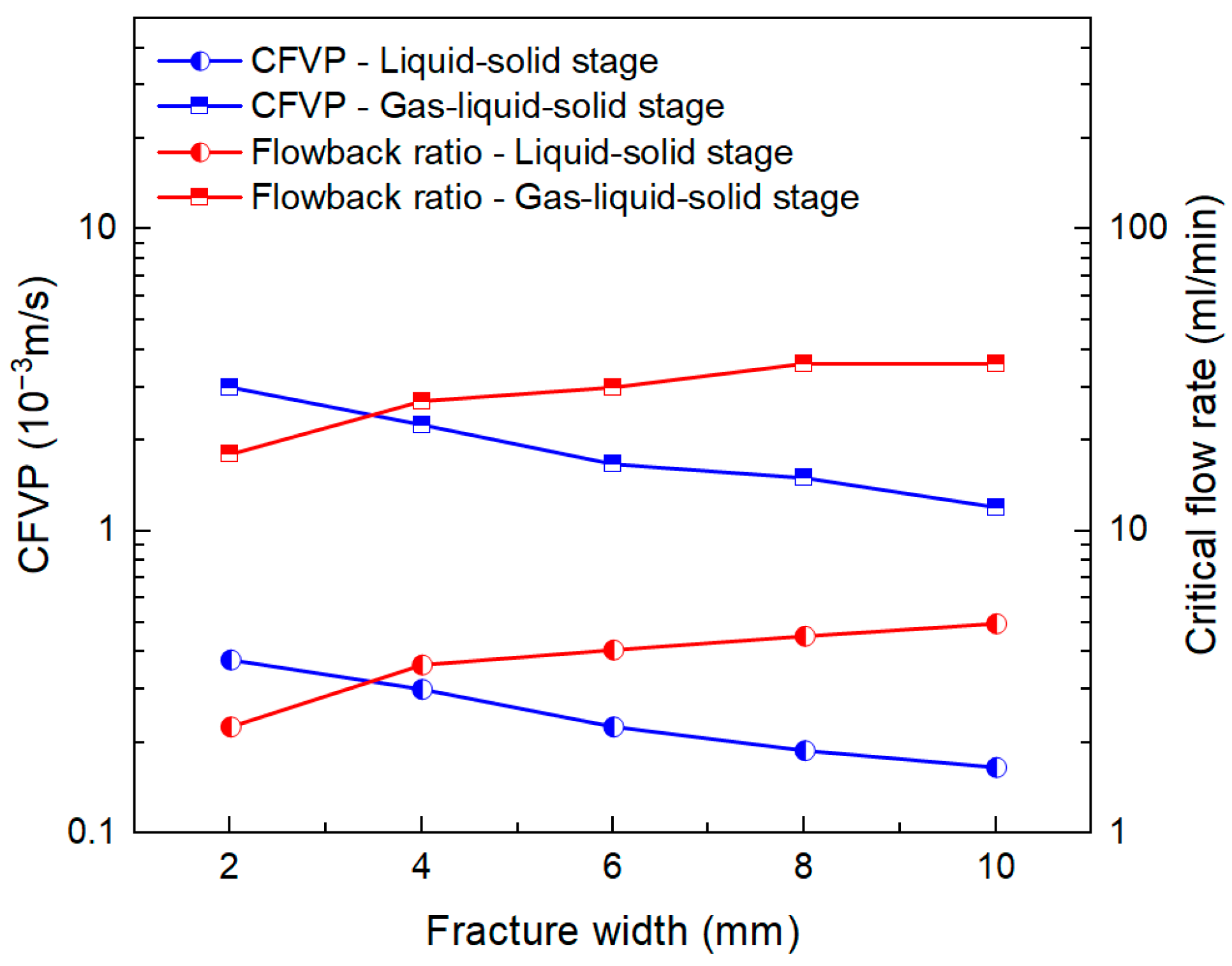

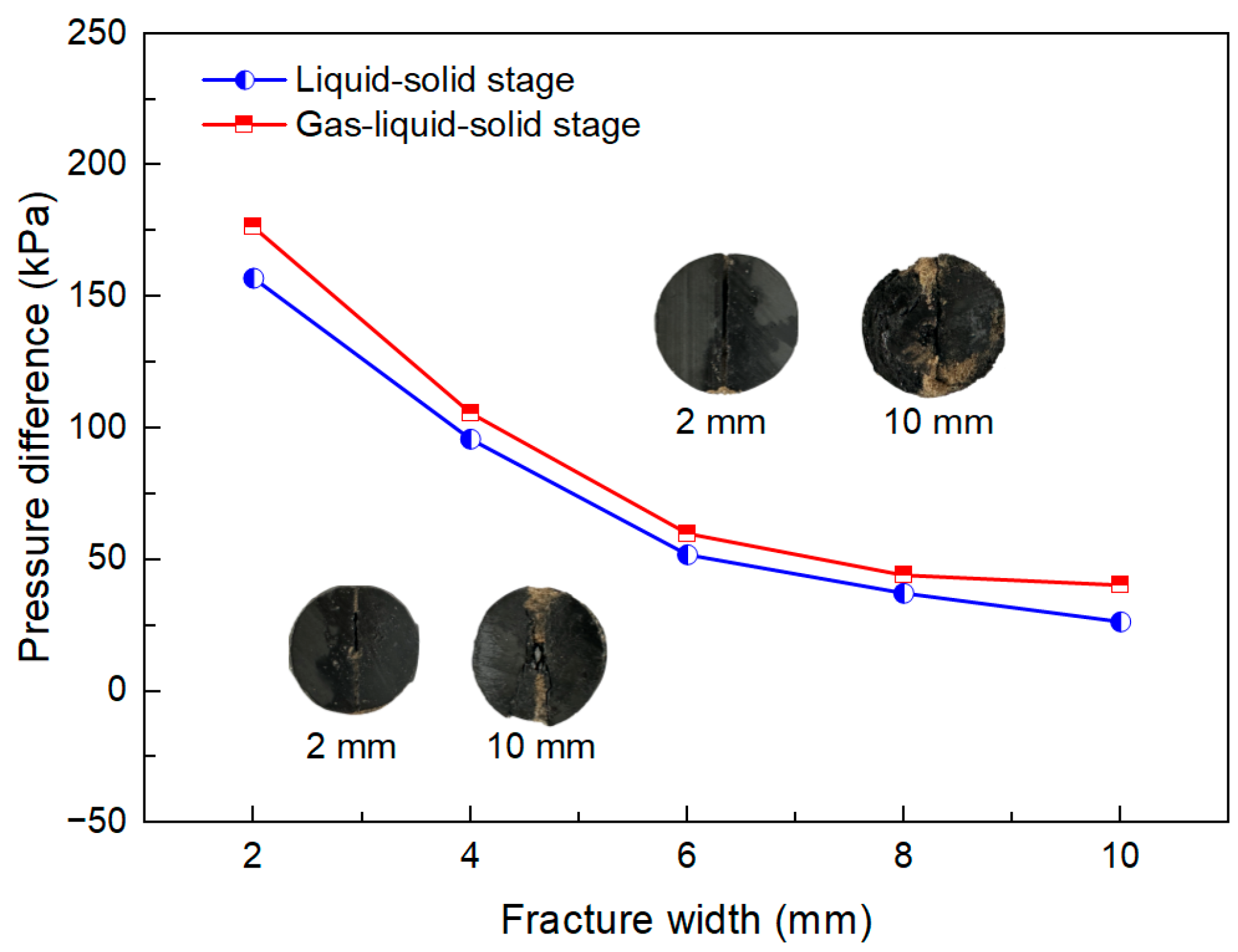

3.2.2. Effect of Fracture Width Stress on CFVP

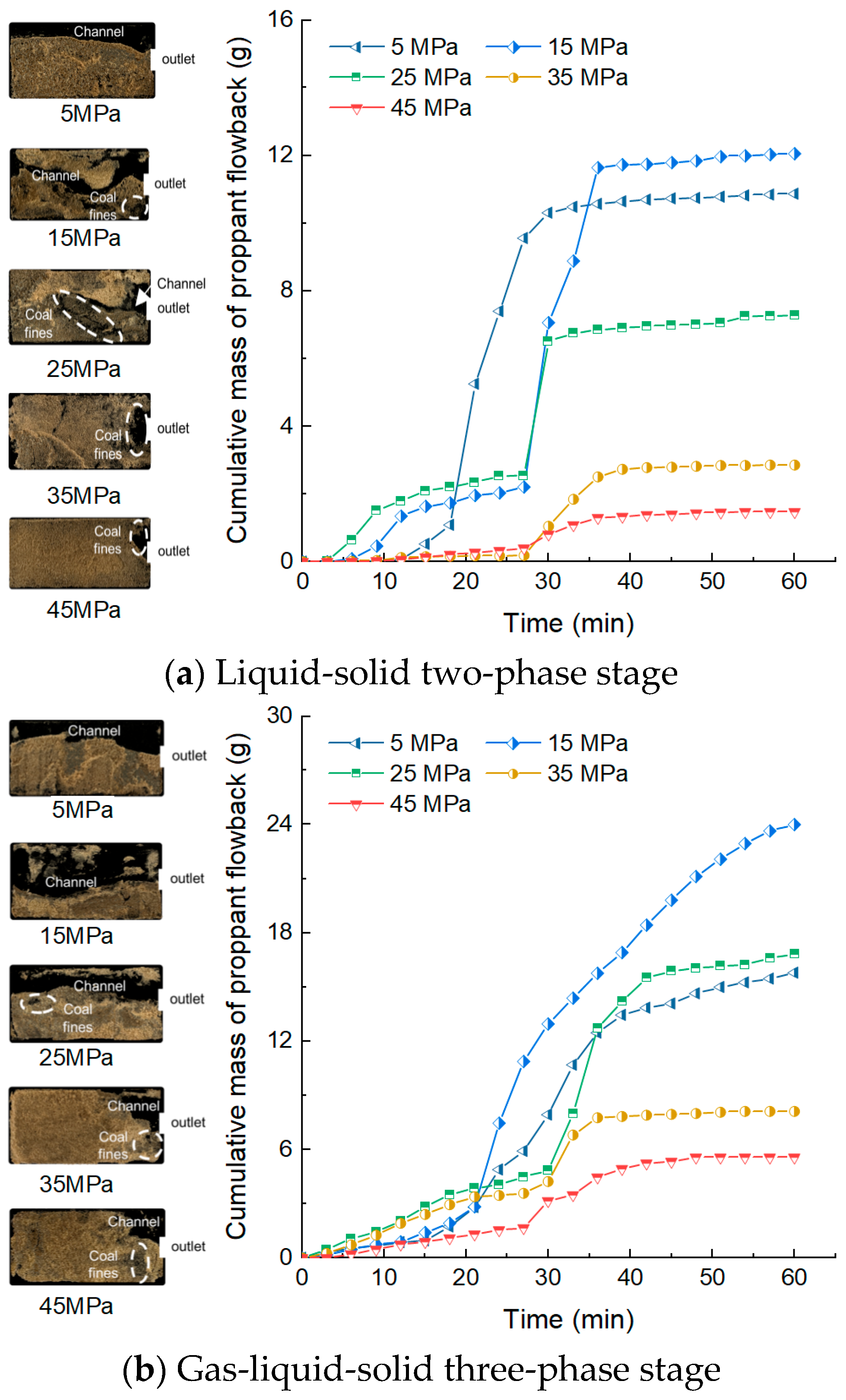

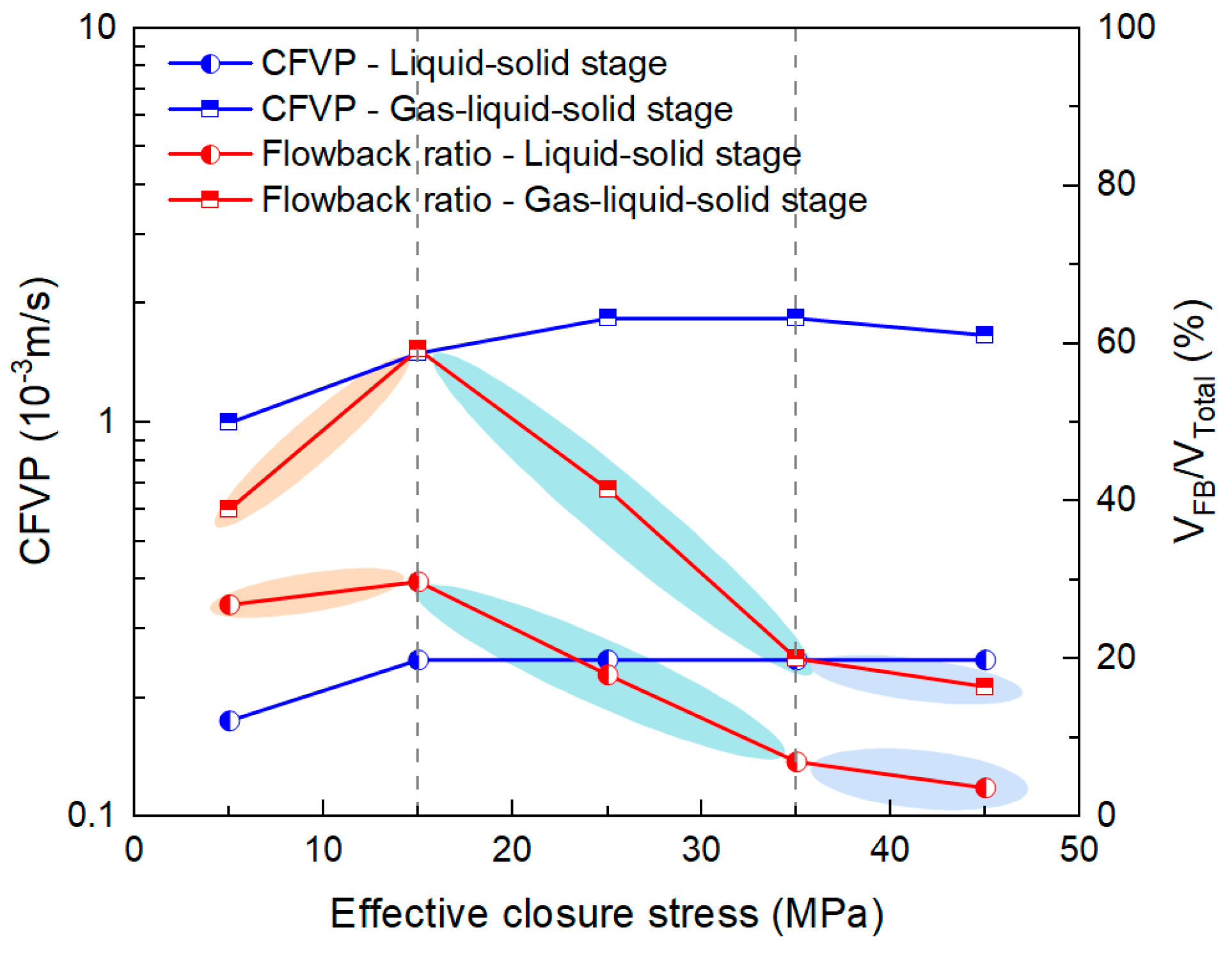

3.2.3. Effect of Effective Closure Stress on CFVP

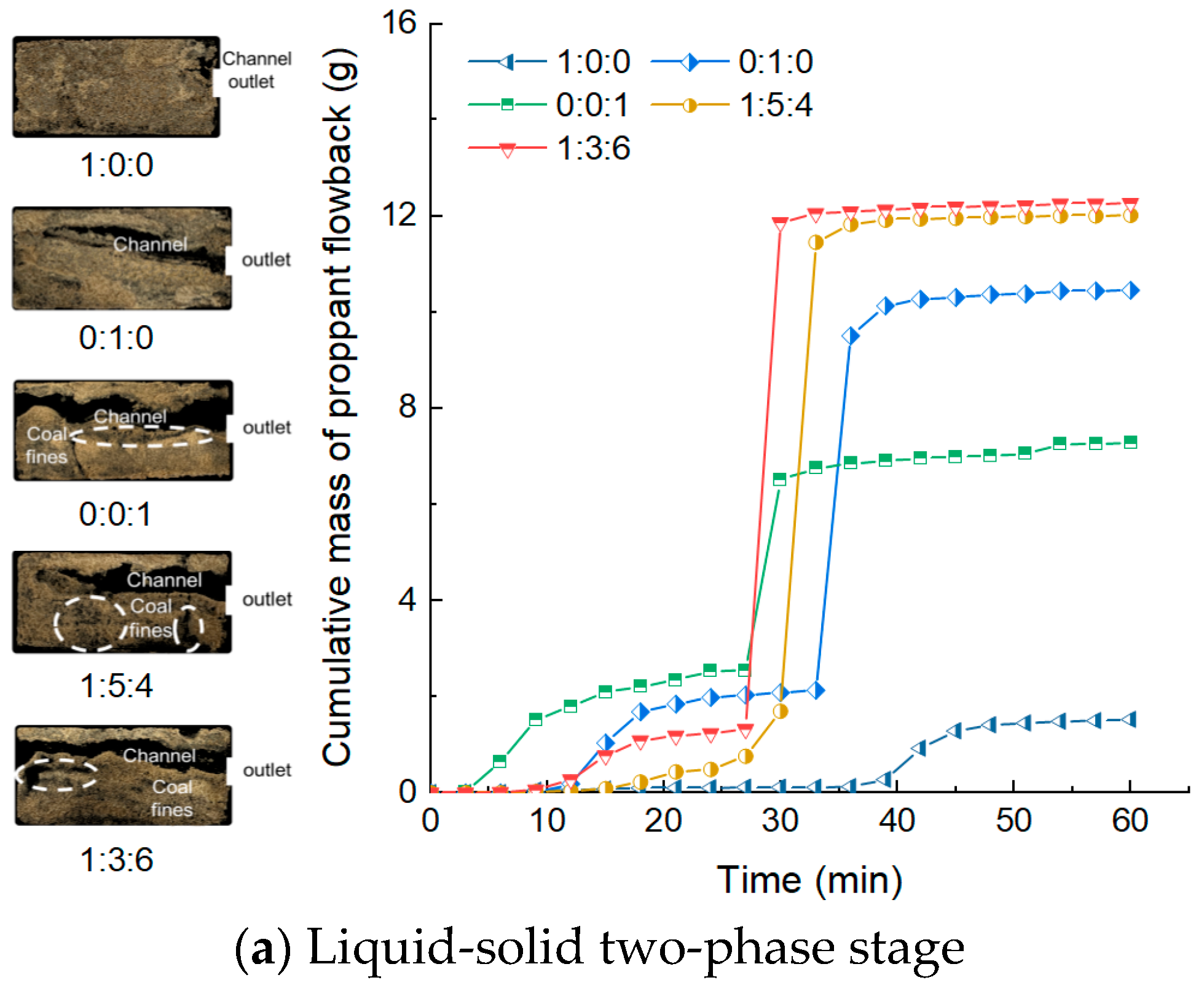

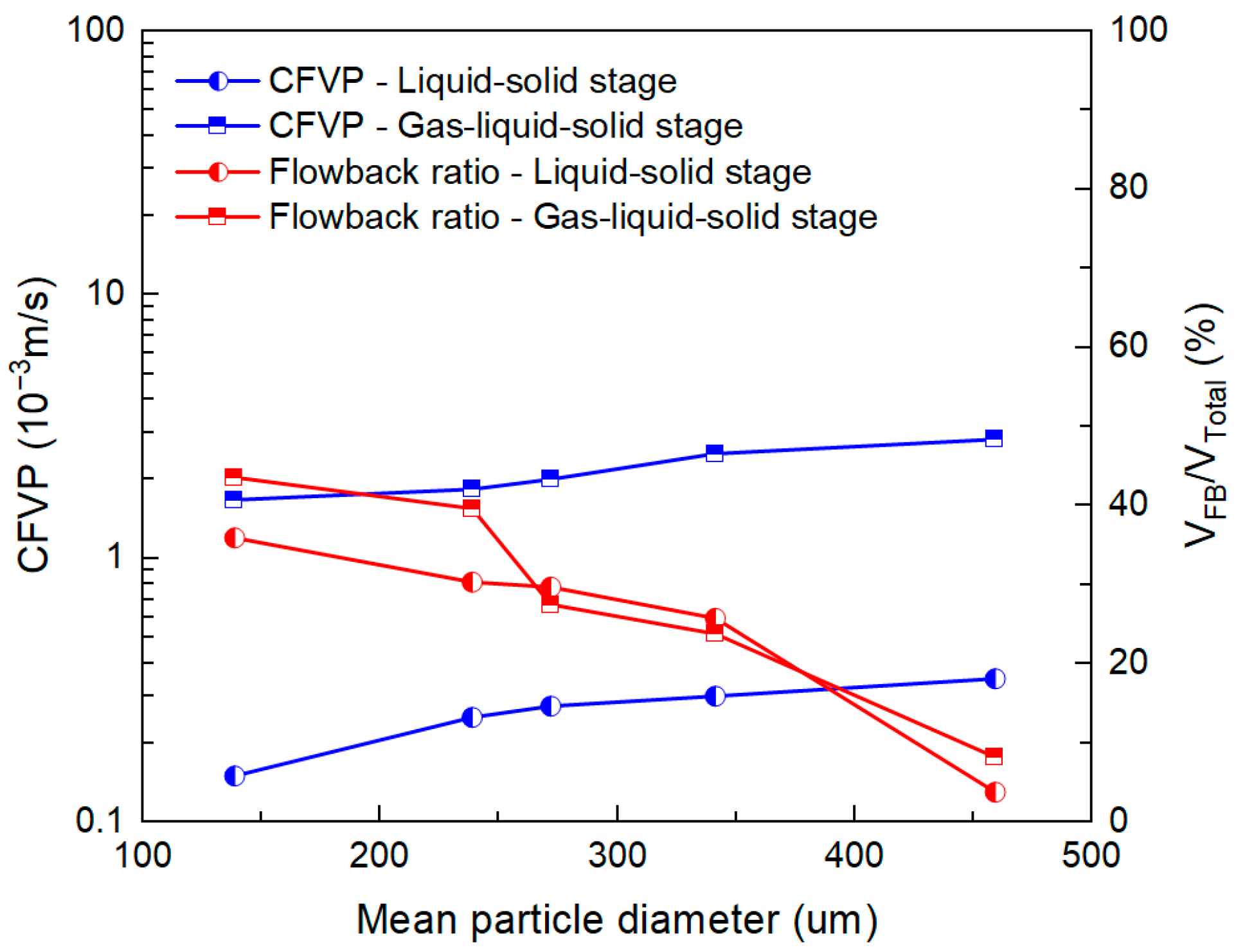

3.2.4. Effect of Proppant Size on CFVP

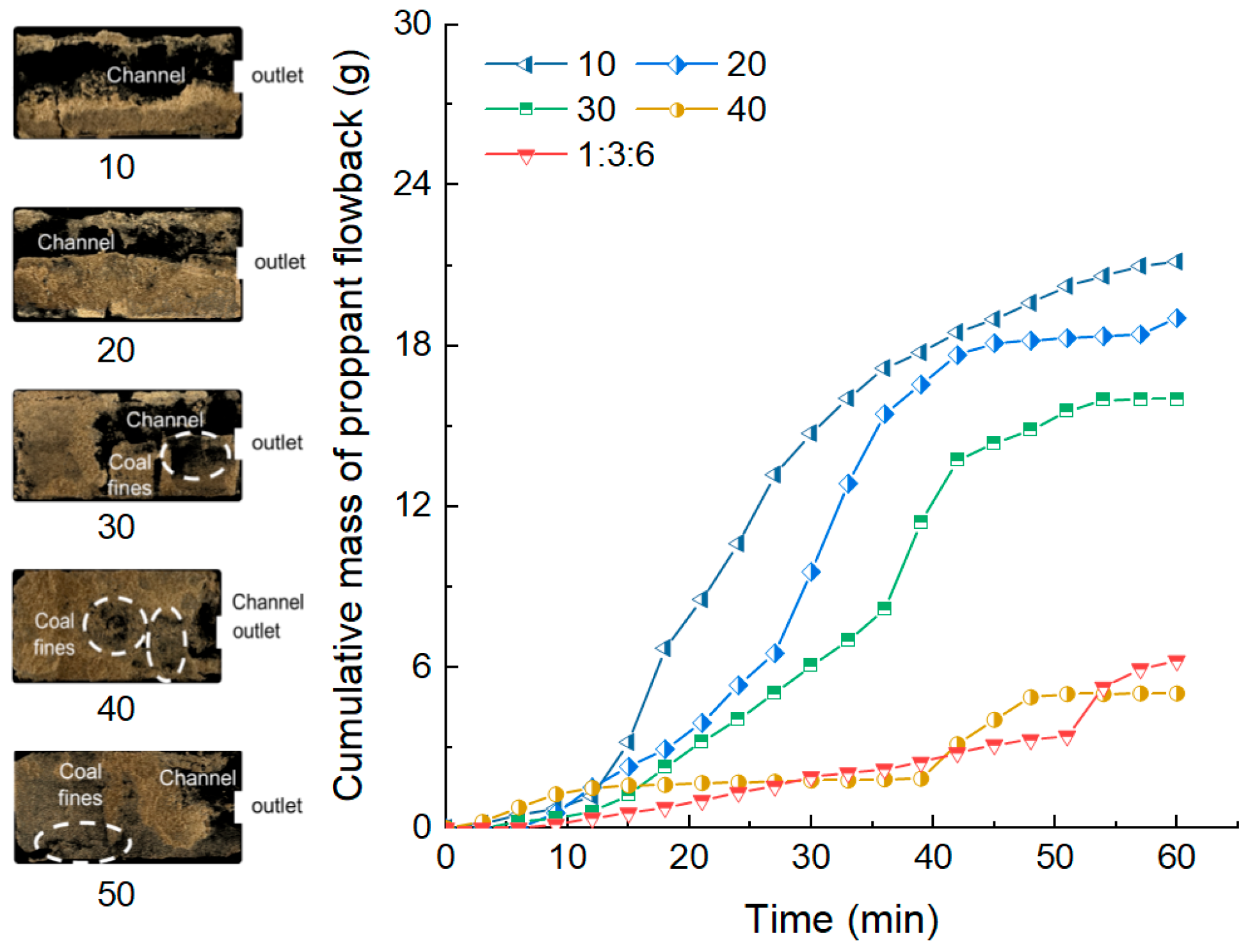

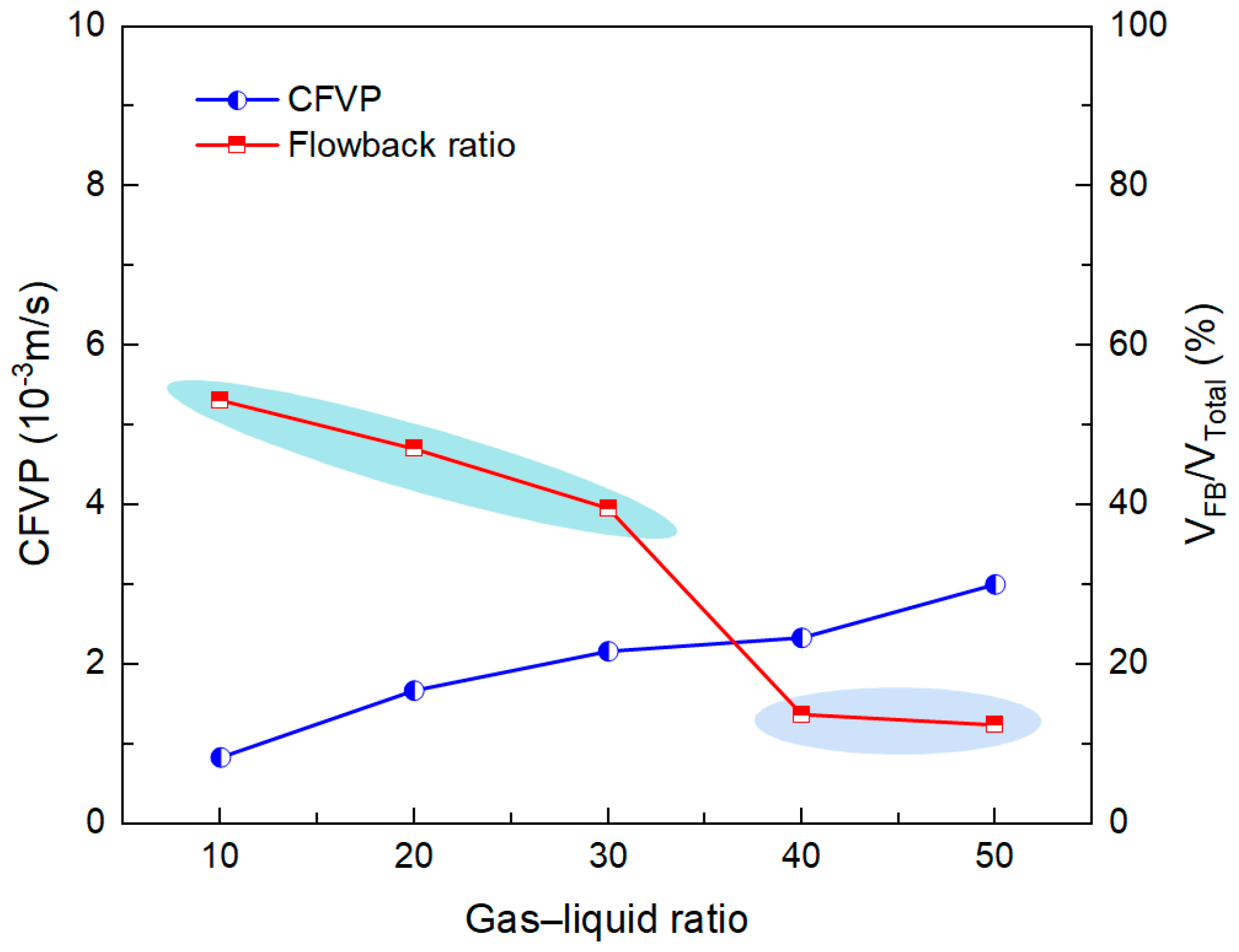

3.2.5. Effect of Gas–Liquid Ratio on CFVP

3.3. Predictive Model for CFVP

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Proppant flowback proceeds in three stages—no flowback, gradual flowback, and rapid flowback—driven by the balance between fluid forces and interparticle contact forces. Gradual flowback occurs when fluid forces overcome gravity to mobilize loosely packed proppants near the outlet, whereas rapid flowback is triggered once the tangential resultant force exceeds the static friction threshold, causing the stable bridging structure to collapse.

- (2)

- Fracture width strongly controls flowback behavior. Wider fractures reduce pack stability and lower CFVP but allow higher critical flow rates. A threshold of 8 mm was identified, beyond which flowback ratios drop sharply while post-flowback conductivity remains high, enabling higher production rates without compromising fracture performance.

- (3)

- Closure stress exerts a dual influence on proppant flowback. At stresses below 15 MPa, enhanced tangential contact forces promote the breakdown of bridge structures, whereby increasing closure stress elevates CFVP but simultaneously accelerates proppant transport. Once the stress exceeds 15 MPa, however, the rise in normal forces increases the static friction threshold and strengthens the overall stability of the proppant pack. Although higher pore-scale flow velocities within the pack cause CFVP to remain nearly constant, the overall flowback rate gradually decreases. Beyond 35 MPa, the proppant pack becomes highly stable, and flowback is largely suppressed.

- (4)

- Increasing the average proppant size raises CFVP and lowers flowback, because larger particles possess greater self-weight and contact stiffness, which increase normal loading and the static-friction threshold, thereby enhancing the mechanical stability of the packed bed. Stepwise placement is recommended, since direct contact between 30/50-mesh and 70/140-mesh particles allows fine particles to infill interstices and weaken the force-chain framework, markedly reducing fracture conductivity.

- (5)

- Higher gas–liquid ratios suppress proppant flowback and raise CFVP by lowering the mixture’s effective density and viscosity and by enhancing gas–liquid interfacial tension effects. These changes diminish drag and pressure-gradient forces on particles while strengthening capillary and interparticle cohesion. Once the gas–liquid ratio in reservoir fractures exceeds about 40, the flowback ratio remains consistently low, permitting a gradual relaxation of production-rate constraints.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFVP | Critical flowback velocity |

| DCBM | Deep coalbed methane |

| EUR | Estimated ultimate recovery |

| CFD-DEM | Computational fluid dynamics and discrete element |

References

- Zou, C.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, H.; Sun, F.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Z.; Yu, R.; Li, S.; Yang, Z.; Wu, S.; et al. China’s Breakthrough in Coal-Rock Gas and Its Significance. Nat. Gas Ind. 2025, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xiong, X.; Ding, R.; Li, Y. Connotation, Enrichment Mechanism and Practical Significance of Coal-Rock Gas. Nat. Gas Ind. 2025, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, S.; He, H.; He, X.; Zhao, Z.; Niu, X.; Xiong, X.; Zhao, Q.; Guo, X.; Hou, Y.; et al. Coal-Rock Gas: Concept, Connotation and Classification Criteria. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Nie, Z.; Sun, W.; Xiong, X.; Xu, B.; Zhang, L.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Theoretical and Technological System for Highly Efficient Development of Deep Coalbed Methane in the Eastern Edge of Erdos Basin. J. China Coal Soc. 2024, 49, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhen, H.; Li, S.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhu, W.; Xu, B.; Yang, Y.; et al. The History and Development Direction of Iterative Upgrading of Deep Coalbed Methane Reservoir Reconstruction Technology—Taking the Daji Block in the Eastern Margin of the Ordos Basin as an Example. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Xu, F.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L.; Ji, L.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, K. Deep Coalbed Methane Production Technology for the Eastern Margin of the Ordos Basin: Advances and Their Implications. Coal Geol. Explor. 2024, 52, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, C.; Powell, J.; Stadnyk, S. Evolving Completion Technologies Mitigate Proppant Flowback. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 9–11 October 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, C.; Green, J.; Abrams, B.; Cabori, L.; Hamori, K.; Harper, A. On-the-Fly Proppant Flowback Control Additive. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Virtual, 26–29 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greff, K.; Greenbauer, S.; Huebinger, K.; Goldfaden, B. The Long-Term Economic Value of Curable Resin-Coated Proppant Tail-in to Prevent Flowback and Reduce Workover Cost. In Proceedings of the SPE/AAPG/SEG Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 25–27 August 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.; Walton, I.; Moore, J.; Brinton, D.; Lund, J. Proppant Backflow: Mechanical and Flow Considerations. Geothermics 2015, 57, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Singh, A.; Lannen, C.; Kim, A.; Menconi, M.; Taylor, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. CounterProp Delivering Beneficial Proppant Flowback Mitigation and Improved Well Productivity—A Success Story from Permian. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 1–3 February 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stim-Lab. Presentation on Proppant Flowback Studies Review; Stim-Lab Proppant Consortium: Austin, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shor, R.J.; Sharma, M.M. Reducing Proppant Flowback from Fractures: Factors Affecting the Maximum Flowback Rate. In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 4–6 February 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.G.; Carlevaro, C.M.; Sánchez, M.; Pugnaloni, L.A. Stability and Conductivity of Proppant Packs during Flowback in Unconventional Reservoirs: A CFD–DEM Simulation Study. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 201, 108381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; He, L.; Dong, B.; Tuerhongbaiyi, N.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. The Mechanism of Proppant Transport during Flowback in Rough Fracture for Supercritical CO2 Fracturing. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 1694–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yao, J.; Li, D.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L. CFD-DEM Simulation of Proppant Pack Stability during Flowback in a Rough Fracture Using Supercritical CO2. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 233, 212599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.S.; Kjorholt, H. Rock Mechanical Principles Help to Predict Proppant Flowback from Hydraulic Fractures. In Proceedings of the SPE/ISRM Rock Mechanics in Petroleum Engineering Conference, Trondheim, Norway, 8–10 July 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garagash, I.A.; Osiptsov, A.A.; Boronin, S.A. Dynamic Bridging of Proppant Particles in a Hydraulic Fracture. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 135, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Shah, S.N. Experimental Investigation of Proppant Flowback Phenomena Using a Large Scale Fracturing Simulator. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 3–6 October 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuprakov, D.; Iuldasheva, A.; Alekseev, A. Criterion of Proppant Pack Mobilization by Filtrating Fluids: Theory and Experiments. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshy, A. Proppant Distribution and Flowback in Off-Balance Hydraulic Fractures. SPE Prod. Facil. 2005, 20, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Wang, J.; Guo, T.; Shen, L.; Liao, H.; Liu, X.; Fan, J.; Hao, T. Optimization on Fracturing Fluid Flowback Model after Hydraulic Fracturing in Oil Well. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 204, 108703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagci, S.; Stolyarov, S. Flowback Production Optimization for Choke Size Management Strategies in Unconventional Wells. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Calgary, AB, Canada, 30 September–2 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Weaver, J.; Van Batenburg, D. Understanding Proppant Flowback. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 3–6 October 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, J.; Feraud, J.P. Stability of Proppant Pack Reinforced with Fiber for Proppant Flowback Control. In Proceedings of the SPE Formation Damage Control Symposium, Lafayette, LA, USA, 14–15 February 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Batenburg, D.; Biezen, E.; Weaver, J. Towards Proppant Back-Production Prediction. In Proceedings of the SPE European Formation Damage Control Conference, The Hague, The Netherlands, 31 May–1 June 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sang, Y.; Guo, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, W.; Tang, B.; Feng, F.; Gou, X.; Zhang, Y. Experimental Study on the Backflow Mechanism of Proppants in Induced Fractures and Fiber Sand Control Under the Condition of Large-Scale and Fully Measurable Flow Field. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 42467–42478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Hao, H.; Zhang, M.; Liang, T. Impacts of Proppant Flowback on Fracture Conductivity in Different Fracturing Fluids and Flowback Conditions. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 6682–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuprakov, D.; Belyakova, L.; Iuldasheva, A.; Alekseev, A.; Syresin, D.; Chertov, M.; Spesivtsev, P.; Salazar Suarez, F.I.; Velikanov, I.; Semin, L.; et al. Proppant Flowback: Can We Mitigate the Risk? In Proceedings of the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference and Exhibition, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 4–6 February 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSebaee, M.; Alekseev, A.; Plyashkevich, V.; Yudin, A.; AlSomali, A.; Chertov, M. Novel Trends in Fracturing Proppant Flowback Control. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Virtual, 26–29 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Singh, A.; Rijken, M.; Reverol, R.; Jones, C.; Milton-Tayler, D.; Grant, S. Experimental Investigation of Proppant Production Mitigation in Liquid-Rich Unconventional Wells. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 3–5 October 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Factors Affecting the Critical Flowback Velocity of Fracturing Fluids and the Long-Term Productivity of Shale Gas Wells. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Lafayette, LA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhiming, W.; Quanshu, Z.; Jian, Z. Fundamental Theory of Coalbed Methane Development; Petroleum Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Hou, W.; Xiong, X.; Xu, B.; Wu, P.; Wang, H.; Feng, K.; Yun, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. The Status and Development Strategy of Coalbed Methane Industry in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Huang, B.; Cheng, Q.; Zhao, X.; Chen, B.; Zhao, L. Mechanism of Single Proppant Pressure Embedded in Coal Seam Fracture. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 7756–7767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huilin, L.; Gidaspow, D. Hydrodynamics of Binary Fluidization in a Riser: CFD Simulation Using Two Granular Temperatures. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2003, 58, 3777–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, S.; Abdalla, M.; Salem, K.G.; Nasr, K.; Emara, R.; Wang, Q.; El-Hoshoudy, A.N. Machine learning prediction of methane, nitrogen, and natural gas mixture viscosities under normal and harsh conditions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zhao, G.Y.; Chen, G.J.; Guo, T.M. Interfacial Tension of (Methane + Nitrogen) + Water and (Carbon Dioxide + Nitrogen) + Water Systems. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2001, 46, 1544–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der, O. Multi-Output Prediction and Optimization of CO2 Laser Cutting Quality in FFF-Printed ASA Thermoplastics Using Machine Learning Approaches. Polymers 2025, 17, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamimoghadam, M.; Dezaki, M.L.; Zolfagharian, A.; Bodaghi, M. Influence of Post-Processing CO2 Laser Cutting and FFF 3D Printing Parameters on the Surface Morphology of PLAs: Statistical Modelling and RSM Optimisation. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2023, 6, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Average Diameter (μm) | Sphericity | Roundness | Turbidity (FTU) | Bulk Density (g/cm3) | Apparent Density (g/cm3) | Crush Resistance (28 MPa) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30/50 mesh | 459.3 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 70 | 1.49 | 2.63 | 7.8 |

| 40/70 mesh | 341.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 83 | 1.47 | 2.67 | 8.8 |

| 70/140 mesh | 138.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 142 | 1.42 | 2.67 | 8.5 |

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle density | 2630 kg/m3 | Static Friction between particles | 0.6 |

| Particle Young’s modulus | 10 GPa | Dynamic Friction between particles | 0.2 |

| Particle Poisson’s ratio | 0.25 | Static Friction between particle and wall | 0.5 |

| Particle size distribution | 1:3:6 | Dynamic Friction between particle and wall | 0.15 |

| Wall density | 1650 kg/m3 | Fracture size | 4 × 2 × 2 mm |

| Wall Young’s modulus | 5 GPa | DEM time step | 3 × 10−8 s |

| Wall Poisson’s ratio | 0.3 | CFD time step | 3 × 10−4 s |

| Fluid viscosity | 1 mPa·s | Simulation time | 3 s |

| Parameter | Maximum Daily Liquid Production (m3) | Maximum Daily Gas Production (×104 m3) | Minimum Principal Stress (MPa) | Fracturing Stages | Clusters Per Stage | Fracture Width (mm) | Average Fracture Height (m) | Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 300 | 10 | 31.8–45.0 | 10–13 | 4–5 | 2–10 | 25 | 61.3–73.4 |

| Core No. | Fracture Width (mm) | Effective Closure Stress (MPa) | Proppant Size Distribution | Gas–Liquid Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FB-L-1~5 | 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 | 25 | 1:3:6 | - |

| FB-L-6~10 | 6 | 5, 15, 25, 35, 45 | 1:3:6 | - |

| FB-L-11~15 | 6 | 25 | 1:0:0, 0:1:0, 0:0:1, 1:5:4, 1:3:6 | - |

| FB-G-1~5 | 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 | 25 | 1:3:6 | 20 |

| FB-G-6~10 | 6 | 5, 15, 25, 35, 45 | 1:3:6 | 20 |

| FB-G-11~15 | 6 | 25 | 1:0:0, 0:1:0, 0:0:1, 1:5:4, 1:3:6 | 20 |

| FB-G-16~20 | 6 | 25 | 1:3:6 | 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 |

| Stage | Fracture Width (mm) | Closure Stress (MPa) | Proppant Size (μm) | Gas–Liquid Ratio | Experimental Value (10−3 m/s) | Model Value (10−3 m/s) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| liquid–solid | 6 | 5 | 238.68 | - | 0.175 | 0.171 | 2.5 |

| 6 | 25 | 271.8 | - | 0.275 | 0.257 | 6.7 | |

| 6 | 45 | 238.68 | - | 0.250 | 0.227 | 9.2 | |

| gas–liquid–solid | 6 | 5 | 238.68 | 20 | 1.000 | 0.887 | 11.3 |

| 6 | 25 | 271.8 | 20 | 2.000 | 1.852 | 7.4 | |

| 6 | 45 | 238.68 | 20 | 1.667 | 1.831 | 9.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, X.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, W.; Huang, T.; Li, B.; Yan, P.; Dai, A. Mechanisms of Proppant Pack Instability and Flowback During the Entire Production Process of Deep Coalbed Methane. Processes 2025, 13, 3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113605

Cai X, Wang Z, Zeng W, Huang T, Li B, Yan P, Dai A. Mechanisms of Proppant Pack Instability and Flowback During the Entire Production Process of Deep Coalbed Methane. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113605

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Xianlu, Zhiming Wang, Wenting Zeng, Tianhao Huang, Binwang Li, Pengyin Yan, and Anna Dai. 2025. "Mechanisms of Proppant Pack Instability and Flowback During the Entire Production Process of Deep Coalbed Methane" Processes 13, no. 11: 3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113605

APA StyleCai, X., Wang, Z., Zeng, W., Huang, T., Li, B., Yan, P., & Dai, A. (2025). Mechanisms of Proppant Pack Instability and Flowback During the Entire Production Process of Deep Coalbed Methane. Processes, 13(11), 3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113605