Analysis of Process Intensification Impact on Circular Economy in Levulinic Acid Purification Schemes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Statement

3. Methodology

- (i)

- Infrastructure for fuel extraction (): includes the facilities and equipment necessary to extract the fuel used in the boiler to satisfy the energy requirements of each process.

- (ii)

- Infrastructure for the boiler (): considers the installation required to generate steam through fuel combustion. This steam is directed to the reboiler of the distillation column, where it transfers heat to the bottom liquid to achieve the partial boiling required for component separation.

- (iii)

- Infrastructure for the LA purification process (): encompasses the equipment and process units required to operate the purification stage.

4. Case Study

4.1. Designs Obtained Through Systematic Synthesis

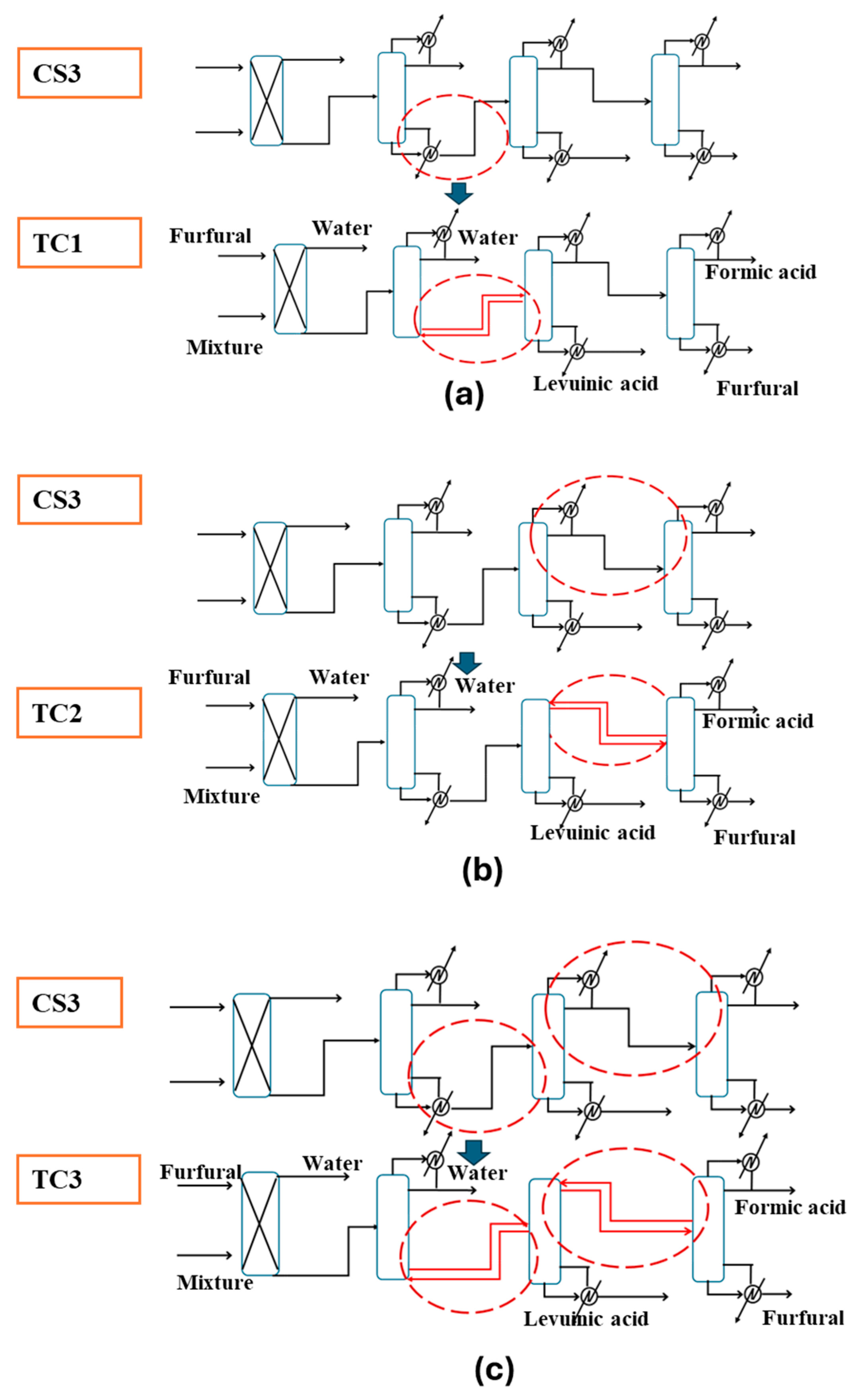

4.1.1. Conventional Designs

4.1.2. Thermally Coupled Schematics

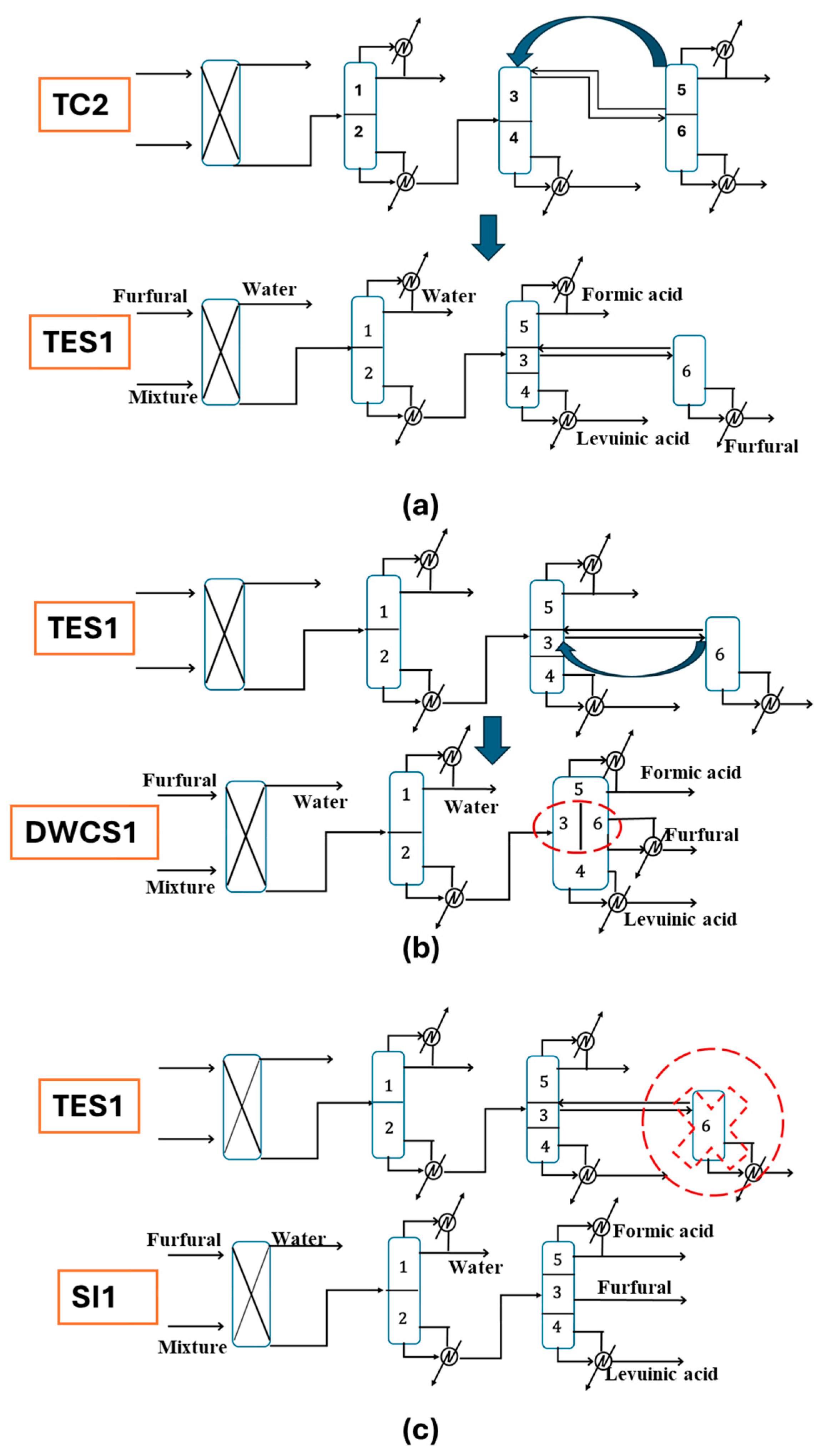

4.1.3. Intensified Designs

4.2. Hybrid DWC–Decanter Intensification

4.3. Evaluation of Circular Economy Indicators

5. Results and Discussion

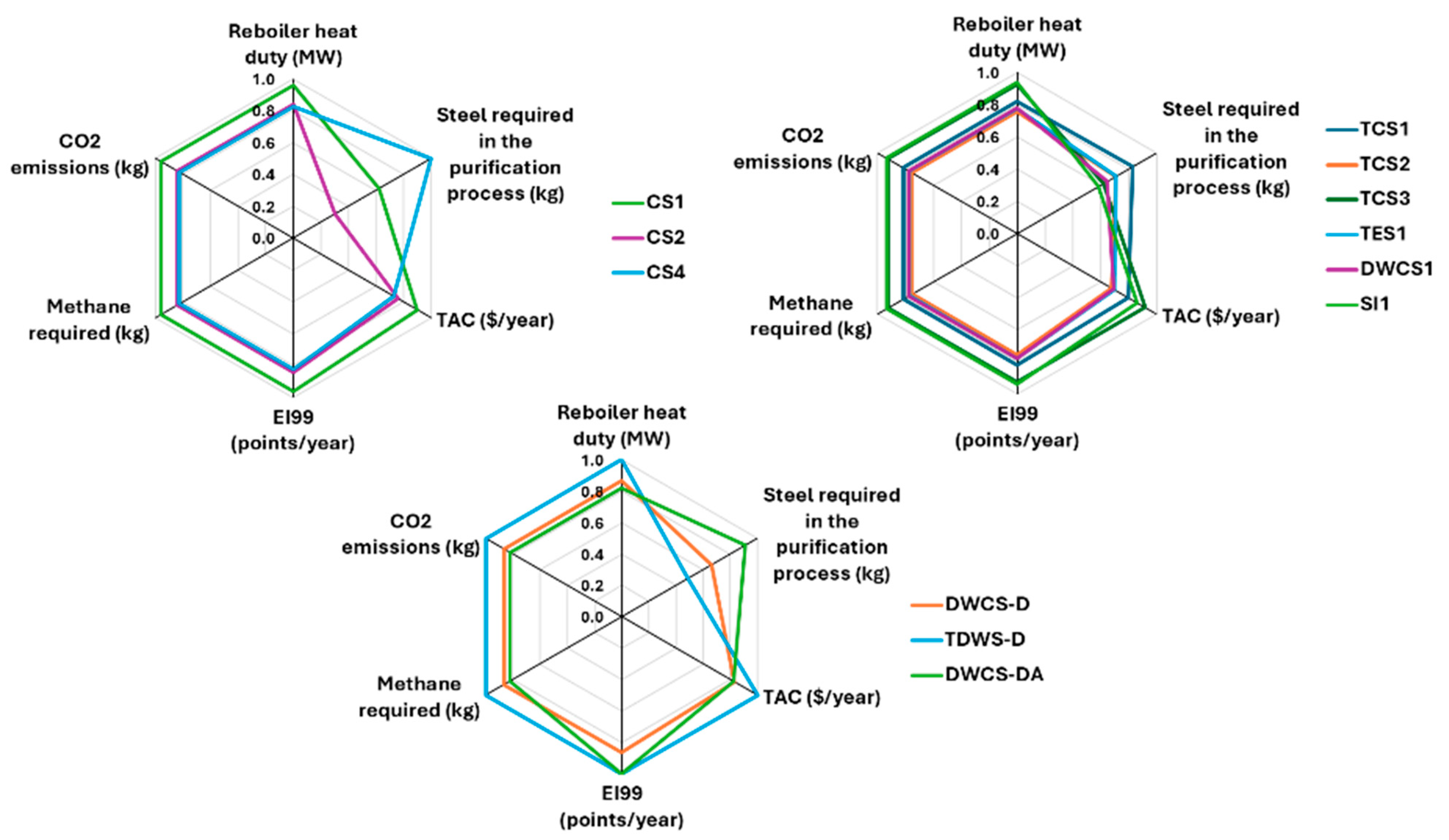

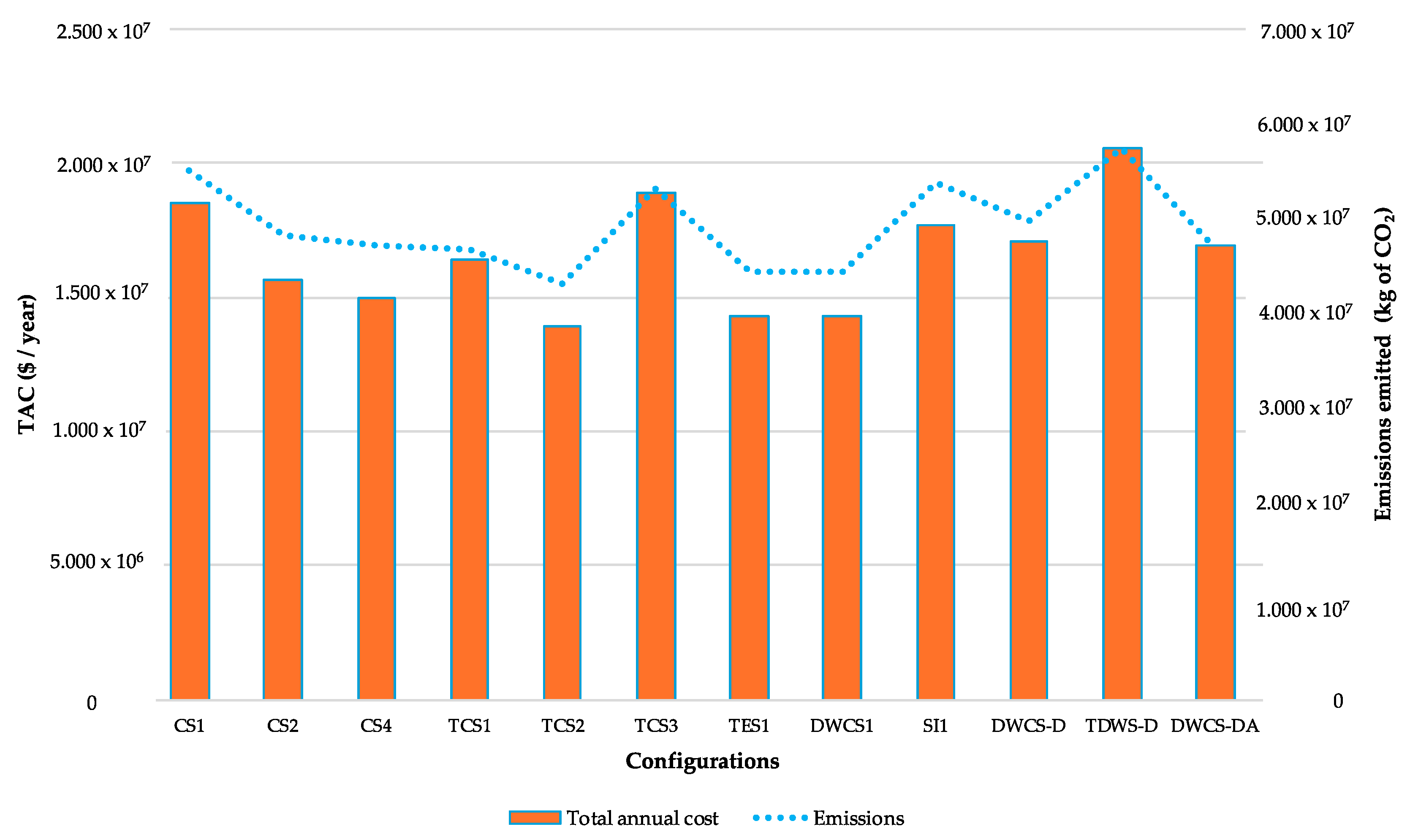

5.1. Evaluation Metrics for the Analyzed Configurations

5.2. Circular Economy Assessment Results

5.3. Analysis of Economic and Environmental Impacts

5.4. Integrated Sustainability and Circularity Assessment

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CS | Conventional Scheme |

| DES | Deep Eutectic Solvents |

| DMR | Relative Material Impact |

| DWCS1 | Dividing wall column sequence |

| ED | Electrodialysis |

| EI99 | Eco-Indicator 99 |

| HMF | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural |

| LA | Levulinic Acid |

| MIBK | Methyl Isobutyl Ketone |

| NRTL-HOC | Non-Random Two Liquid—Hayden–O’Connell model |

| SI1 | N–1 column sequence |

| TAC | Total Annual Cost |

| TC | Thermally Coupled Scheme |

| TES1 | Thermally equivalent system configuration |

| TOA | Trioctylamine |

| TOPO | Trioctylphosphine Oxide |

References

- Hayes, G.C.; Becer, C.R. Levulinic acid: A sustainable platform chemical for novel polymer architectures. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 4068–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errico, M.; Stateva, R.P.; Leveneur, S. Novel intensified alternatives for purification of levulinic acid recovered from lignocellulosic biomass. Processes 2021, 9, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis-Sanchez, J.L.; Alcocer-Garcia, H.; Sanchez-Ramírez, E.; Segovia-Hernandez, J.G. Innovative reactive distillation process for levulinic acid production and purification. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 183, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meramo-Hurtado, S.I.; Ojeda, K.A.; Sanchez-Tuiran, E. Environmental and safety assessments of industrial production of levulinic acid via acid-catalyzed dehydration. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 22302–22312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozell, J.J.; Moens, L.; Elliott, D.C.; Wang, Y.; Neuenscwander, G.G.; Fitzpatrick, S.W.; Bilski, R.J.; Jarnefeld, J.L. Production of levulinic acid and use as a platform chemical for derived products. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2000, 28, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, F.; Farooq, M.; Ramli, A.; Naeem, A.; Khan, I.W.; Saeed, T.; Khan, J. Levulinic acid production from waste corncob biomass using an environmentally benign WO3-grafted ZnCo2O4@CeO2 bifunctional heterogeneous catalyst. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, G.; Brangeli, I.; Peeters, M.; Tedesco, S. Solid residue and by-product yields from acid-catalysed conversion of poplar wood to levulinic acid. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 1647–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobuś, N.; Czekaj, I. Catalytic transformation of biomass-derived glucose by one-pot method into levulinic acid over Na-BEA zeolite. Processes 2022, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Silva, J.F.; Maciel Filho, R.; Wolf Maciel, M.R. Process design and technoeconomic assessment of the extraction of levulinic acid from biomass hydrolysate using n-butyl acetate, hexane, and 2-methyltetrahydrofuran. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 11031–11041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Farooq, U.; Bary, G.; Azim, M.M.; Zhao, X. Sustainable production of levulinic acid and its derivatives for fuel additives and chemicals: Progress, challenges, and prospects. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 9198–9238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, W.; Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Sun, W. Optimization and purification of levulinic acid extracted from bagasse. Sugar Tech 2020, 22, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Shende, D.Z.; Wasewar, K.L. Extractive separation of levulinic acid using natural and chemical solvents. Chem. Data Collect. 2020, 28, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, T.; Blahusiak, M.; Babic, K.; Schuur, B. Reactive extraction and recovery of levulinic acid, formic acid and furfural from aqueous solutions containing sulphuric acid. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 185, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveiro, E.; González, B.; Domínguez, Á. Extraction of adipic, levulinic and succinic acids from water using TOPO-based deep eutectic solvents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 241, 116692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habe, H.; Kondo, S.; Sato, Y.; Hori, T.; Kanno, M.; Kimura, N.; Koike, H.; Kirimura, K. Electrodialytic separation of levulinic acid catalytically synthesized from woody biomass for use in microbial conversion. Biotechnol. Prog. 2017, 33, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhary, A.; Leitch, M.; Liao, B.Q. Liquid–liquid extraction technology for resource recovery: Applications, potential, and perspectives. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 40, 101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, A.B.; Eral, H.B.; Schuur, B. Industrial Separation Processes: Fundamentals; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Márquez, C.; Al-Thubaiti, M.M.; Martín, M.; El-Halwagi, M.M.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. Processes intensification for sustainability: Prospects and opportunities. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 2428–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Hernández, J.G.; Hernández, S.; Cossío-Vargas, E.; Sánchez-Ramírez, E. Challenges and opportunities in process intensification to achieve the UN’s 2030 agenda: Goals 6, 7, 9, 12 and 13. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2023, 192, 109507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer-García, H.; Segovia-Hernández, J.G.; Prado-Rubio, O.A.; Sánchez-Ramírez, E.; Quiroz-Ramírez, J.J. Multi-objective optimization of intensified processes for the purification of levulinic acid involving economic and environmental objectives. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2019, 136, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronci, S.; Garau, D.; Stateva, R.P.; Cholakov, G.; Wakeham, W.A.; Errico, M. Analysis of hybrid separation schemes for levulinic acid separation by process intensification and assessment of thermophysical properties impact. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 310, 123166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer-García, H.; Segovia-Hernández, J.G.; Sánchez-Ramírez, E.; Caceres-Barrera, C.R.; Hernández, S. Sequential synthesis methodology in the design and optimization of sustainable distillation sequences for levulinic acid purification. Bioenergy Res. 2024, 17, 1724–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinderer, S.; Brändle, L.; Kuckertz, A. Transition to a sustainable bioeconomy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A. Strategic sustainable assessment of retrofit design for process performance evaluation. In Sustainability in the Design, Synthesis and Analysis of Chemical Engineering Processes; Ruiz-Mercado, G., Cabezas, H., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejarano, P.-A.C.; Rodriguez-Miranda, J.-P.; Maldonado-Astudillo, R.I.; Maldonado-Astudillo, Y.I.; Salazar, R. Circular Economy Indicators for the Assessment of Waste and By-Products from the Palm Oil Sector. Processes 2022, 10, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, Z.; Kulczycka, J.; Banach, M.; Makara, A. A complex circular-economy quality indicator for assessing production systems at the micro level. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Arévalo, T.I.; Díaz-Alvarado, F.A.; Tovar-Facio, J.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. The impact of circular economy indicators in the optimal planning of energy systems. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 44, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.; Martins, C.I.; Simoes, R. Circularity micro-indicators for plastic packaging and their relation to circular economy principles and design tools. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.E.; Han, J.; Burnham, A.; Dunn, J.B.; Wang, M. Life-Cycle Analysis of Shale Gas and Natural Gas; Technical Report ANL/ESD/11-11; Argonne National Laboratory: Argonne, IL, USA, 2011. Available online: https://publications.anl.gov/anlpubs/2012/01/72060.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Brit Boilers. SZS Series Gas Boiler. Available online: https://www.britboilers.com/products/szs-series-gas-boiler.html (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Barma, M.C.; Saidur, R.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Allouhi, A.; Akash, B.A.; Sait, S.M. A review on boilers energy use, energy savings, and emissions reductions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 970–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkaloglu, S.; Cooper, J.; Hawkes, A. Methane emissions along biomethane and biogas supply chains are underestimated. One Earth 2022, 5, 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Agnew, J. Catalytic combustion of coal mine ventilation air methane. Fuel 2006, 85, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubert, E.A.; Brandt, A.R. Three considerations for modeling natural gas system methane emissions in life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNIDO. Manual for Industrial Steam Systems Assessment and Optimization. 2016. Available online: https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/2017-11/SSO-Manual-Print-FINAL-20161109-One-Page-V2.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

| Stage Infrastructure | Material Requirements | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Fuel extraction | 2.459 × 10−5 | kg Sbeq/kg of natural gas extracted |

| Steam boiler | 2.790 × 101 | kg Sbeq/MW |

| Purification process | 1.040 × 10−2 | kg Sbeq/kg of steel |

| Configuration | Reboiler Heat Duty (MW) | Steel Required in the Purification Process (kg) | TAC ($/Year) | EI99 (Points/Year) | Methane Required (kg) | CO2 Emissions (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS1 | 3.098 × 101 | 1.629 × 104 | 1.854 × 107 | 5.359 × 109 | 2.009 × 107 | 5.526 × 107 |

| CS2 | 2.716 × 101 | 7.974 × 103 | 1.562 × 107 | 4.699 × 109 | 1.762 × 107 | 4.845 × 107 |

| CS4 | 2.658 × 101 | 2.623 × 104 | 1.494 × 107 | 4.597 × 109 | 1.724 × 107 | 4.740 × 107 |

| TCS1 | 2.637 × 101 | 2.176 × 104 | 1.638 × 107 | 4.562 × 109 | 1.710 × 107 | 4.704 × 107 |

| TCS2 | 2.435 × 101 | 1.848 × 104 | 1.393 × 107 | 4.213 × 109 | 1.580 × 107 | 4.344 × 107 |

| TCS3 | 2.985 × 101 | 1.614 × 104 | 1.890 × 107 | 5.140 × 109 | 1.936 × 107 | 5.325 × 107 |

| TES1 | 2.499 × 101 | 1.852 × 104 | 1.432 × 107 | 4.350 × 109 | 1.621 × 107 | 4.457 × 107 |

| DWCS1 | 2.508 × 101 | 1.688 × 104 | 1.426 × 107 | 4.337 × 109 | 1.627 × 107 | 4.473 × 107 |

| SI1 | 3.016 × 101 | 1.528 × 104 | 1.770 × 107 | 5.218 × 109 | 1.957 × 107 | 5.381 × 107 |

| DWCS-D | 2.793 × 101 | 1.733 × 104 | 1.710 × 107 | 4.832 × 109 | 1.812 × 107 | 4.982 × 107 |

| TDWS-D | 3.225 × 101 | 1.276 × 104 | 2.057 × 107 | 5.580 × 109 | 2.092 × 107 | 5.753 × 107 |

| DWCS-DA | 2.648 × 101 | 2.387 × 104 | 1.694 × 107 | 5.581 × 109 | 1.717 × 107 | 4.723 × 107 |

| Configuration | Fuel Extraction (kg Sbeq) | Steam Boiler (kg Sbeq) | Purification (kg Sbeq) | Total (kg Sbeq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS1 | 4.941 × 102 | 8.644 × 102 | 1.694 × 102 | 1.528 × 103 |

| CS2 | 4.332 × 102 | 7.579 × 102 | 8.293 × 101 | 1.274 × 103 |

| CS4 | 4.239 × 102 | 7.416 × 102 | 2.727 × 102 | 1.438 × 103 |

| TCS1 | 4.206 × 102 | 7.358 × 102 | 2.263 × 102 | 1.383 × 103 |

| TCS2 | 3.884 × 102 | 6.795 × 102 | 1.922 × 102 | 1.260 × 103 |

| TCS3 | 4.761 × 102 | 8.329 × 102 | 1.678 × 102 | 1.477 × 103 |

| TES1 | 3.985 × 102 | 6.972 × 102 | 1.926 × 102 | 1.288 × 103 |

| DWCS1 | 4.000 × 102 | 6.998 × 102 | 1.756 × 102 | 1.275 × 103 |

| SI1 | 4.811 × 102 | 8.417 × 102 | 1.589 × 102 | 1.482 × 103 |

| DWCS-D | 4.455 × 102 | 7.793 × 102 | 1.802 × 102 | 1.405 × 103 |

| TDWS-D | 5.144 × 102 | 9.000 × 102 | 1.327 × 102 | 1.547 × 103 |

| DWCS-DA | 4.223 × 102 | 7.388 × 102 | 2.483 × 102 | 1.409 × 103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrano-Arévalo, T.I.; Alcocer-García, H.; Ramírez-Márquez, C.; Ponce-Ortega, J.M. Analysis of Process Intensification Impact on Circular Economy in Levulinic Acid Purification Schemes. Processes 2025, 13, 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113496

Serrano-Arévalo TI, Alcocer-García H, Ramírez-Márquez C, Ponce-Ortega JM. Analysis of Process Intensification Impact on Circular Economy in Levulinic Acid Purification Schemes. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113496

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano-Arévalo, Tania Itzel, Heriberto Alcocer-García, César Ramírez-Márquez, and José María Ponce-Ortega. 2025. "Analysis of Process Intensification Impact on Circular Economy in Levulinic Acid Purification Schemes" Processes 13, no. 11: 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113496

APA StyleSerrano-Arévalo, T. I., Alcocer-García, H., Ramírez-Márquez, C., & Ponce-Ortega, J. M. (2025). Analysis of Process Intensification Impact on Circular Economy in Levulinic Acid Purification Schemes. Processes, 13(11), 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113496