The Validation–Deployment Gap in Agricultural Information Systems: A Systematic Technology Readiness Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design and Guiding Framework

- Selected databases and justification for inclusion.

- Boolean search strings using controlled vocabulary.

- Temporal and language boundaries.

- Inclusion/exclusion criteria with operational definitions.

- Data extraction variables aligned with research questions; quality assessment criteria adapted from CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programmed) [22]

- Technology–Performance Matrix, mapping technologies to evaluation metrics (accuracy, latency, scalability, cost).

- Implementation–Maturity Matrix, linking Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) with validation evidence and field deployment duration.

- Barrier–Opportunity Matrix, quantifying adoption constraints and enabling factors extracted from the discussion sections of each paper.

2.2. Database Selection and Justification

- Scopus (Elsevier): Broad peer-reviewed coverage in agriculture, computer science, and economics (~27,000 journals) [23].

- Web of Science (WoS): Emphasizes high-impact journals with rigorous peer review and citation tracking [24].

- IEEE Xplore: Provides technical depth on IoT, blockchain architectures, machine learning models, and recommendation systems [25].

2.3. Search Strategy and Query Development

- (“blockchain” OR “IoT” OR “artificial intelligence”) AND (“agriculture” OR “agricultural marketing”);

- (“e-commerce” OR “digital agricultural markets”) AND (“sustainability” OR “supply chain efficiency”);

- (“agricultural marketing strategies” OR “business models” OR “local markets” OR “collaborative economy”) AND (“trends” OR “digital transformation” OR “agri-food innovation”);

- (“emerging agricultural technologies” OR “digital transformation in farming”) AND (“market access” OR “efficient commercialization” OR “agricultural logistics”).

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Publication type: Peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings (IEEE), and systematic reviews.

- Language: English (due to resource constraints and research team linguistic capabilities).

- Temporal scope: Published between January 2019 and April 2025 (capturing recent developments while maintaining currency).

- Thematic relevance: Primary focus on digital technologies (Blockchain, AI/ML, IoT, recommendation systems, Big Data) applied to agricultural marketing, commercialization, distribution, or market access.

- Methodological standards: Empirical studies, case studies, systematic reviews, or conceptual frameworks with clear methodology.

- Accessibility: Full-text available through institutional subscriptions or open access repositories.

2.4.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Publication type: Books, dissertations, editorials, preprints without peer review.

- Thematic scope: Studies lacking computational/algorithmic contribution or implementation details.

- In this review, the criterion “lack of clear methodology” was applied when an article did not specify its data sources, analytical procedures, or validation approach. During full-text screening, studies that described technological proposals without explaining how results were obtained or evaluated were excluded. This decision process was aligned with the quality assessment described in Section 2.6 to ensure consistency.

- Duplication: Multiple publications of identical research (retained most comprehensive version).

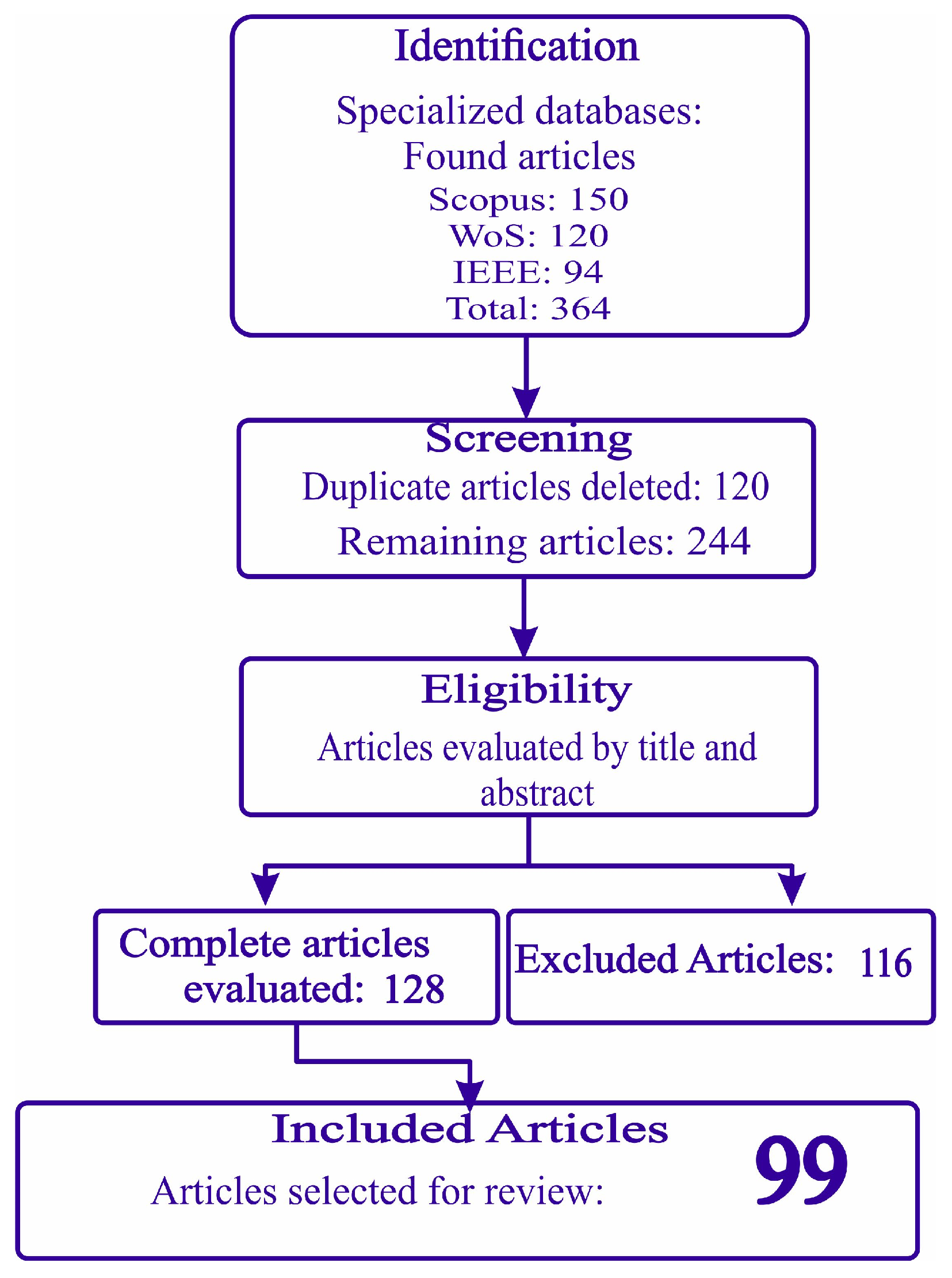

2.5. Selection Process and PRISMA Flow

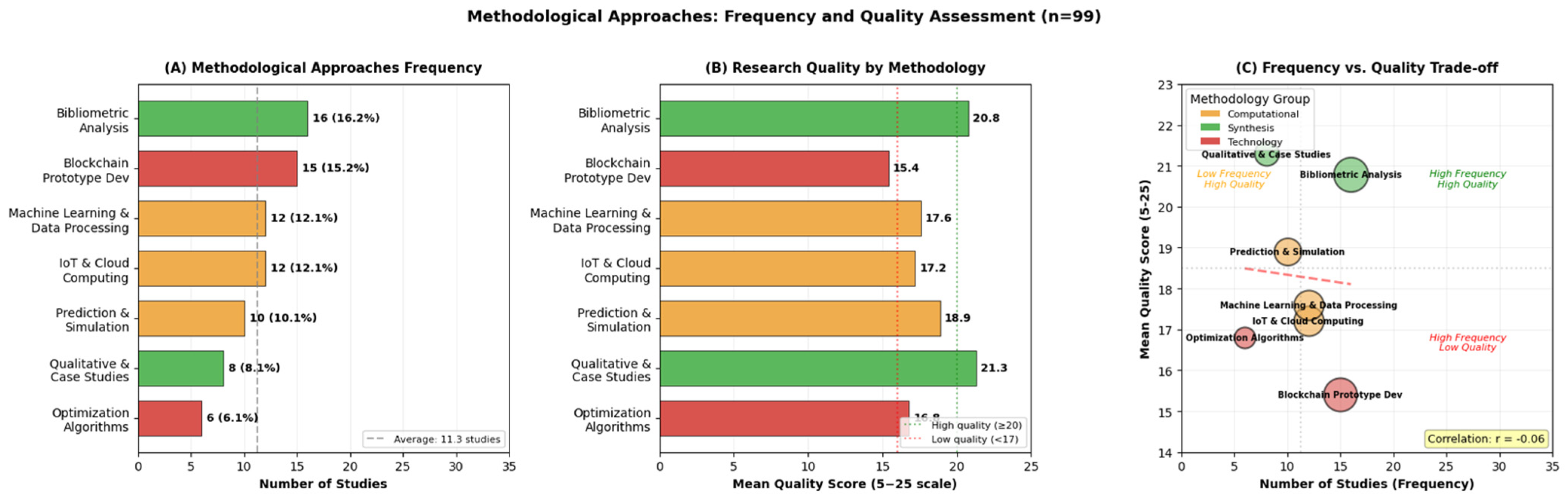

2.6. Quality Assessment

- Research design clarity: Explicit methodology, clear research questions, appropriate methods for objectives.

- Data quality: Sample size adequacy, data source transparency, measurement instrument validity.

- Analytical rigor: Statistical techniques appropriateness, result reproducibility, explicit limitation acknowledgment.

- Implementation maturity: Technology Readiness Level (TRL) reporting, field validation evidence, deployment assessment beyond prototype.

- Economic consideration: Cost analysis presence, economic viability discussion, farmer perspective inclusion.

- Overall quality scores (5–25 points) enabled categorization:

- High quality (20–25 points): 15 articles (15.2%)—robust methodology, field validation, economic analysis.

- Medium quality (15–19 points): 62 articles (62.6%)—clear methodology, limited field validation, minimal economic assessment.

- Low quality (10–14 points): 22 articles (22.2%)—preliminary findings, prototype-only, absent economic analysis.

2.7. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.8. Analytical Framework

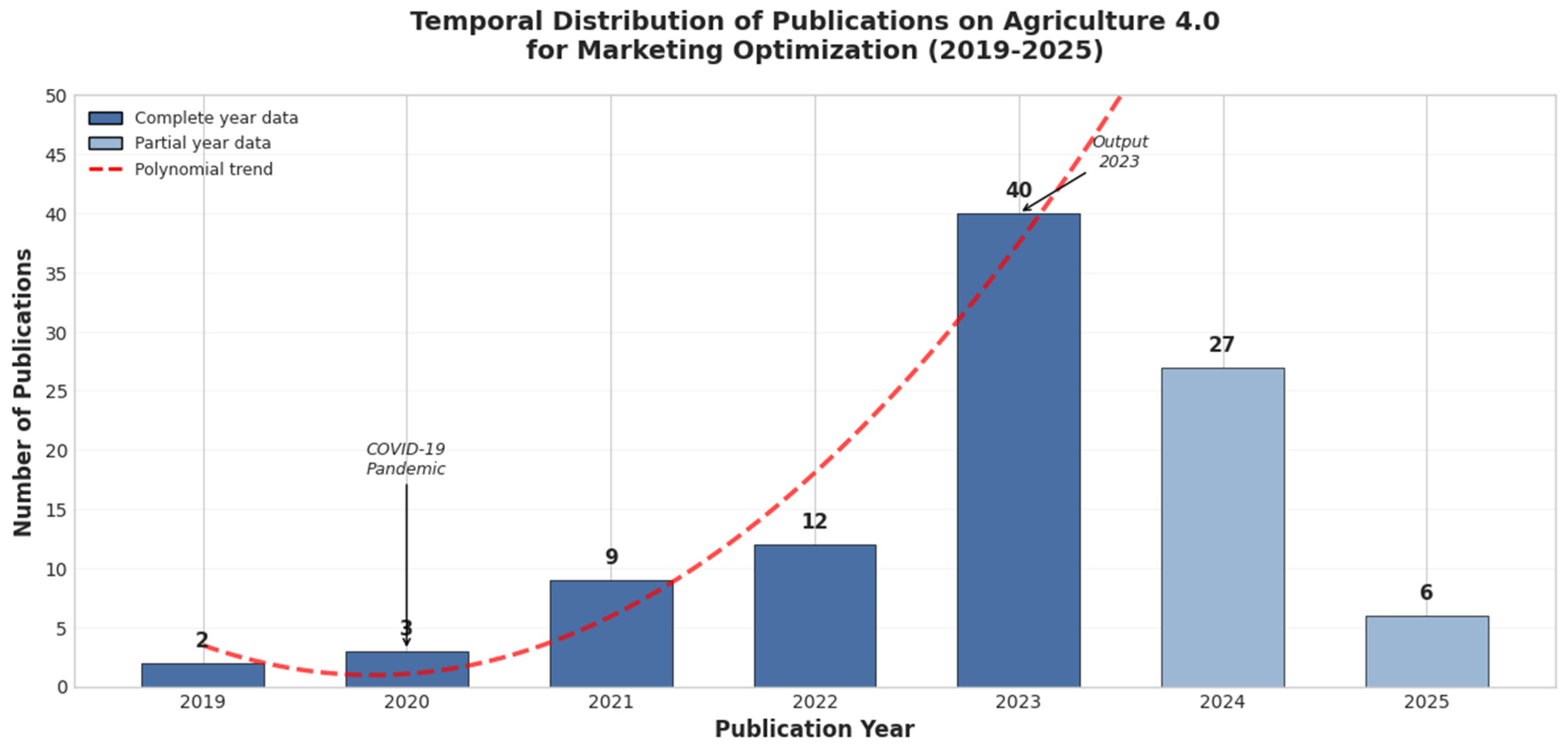

- Frequency distributions and annual publication trends (2019–2024).

- Regional research mapping using author institutional affiliations.

- Technology prevalence analysis by category and application domain.

- Citation impact evaluation using Google Scholar citation data.

- Performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, F1-score, R2, RMSE, latency) were aggregated using range, mean when available, and frequency of metric reporting.

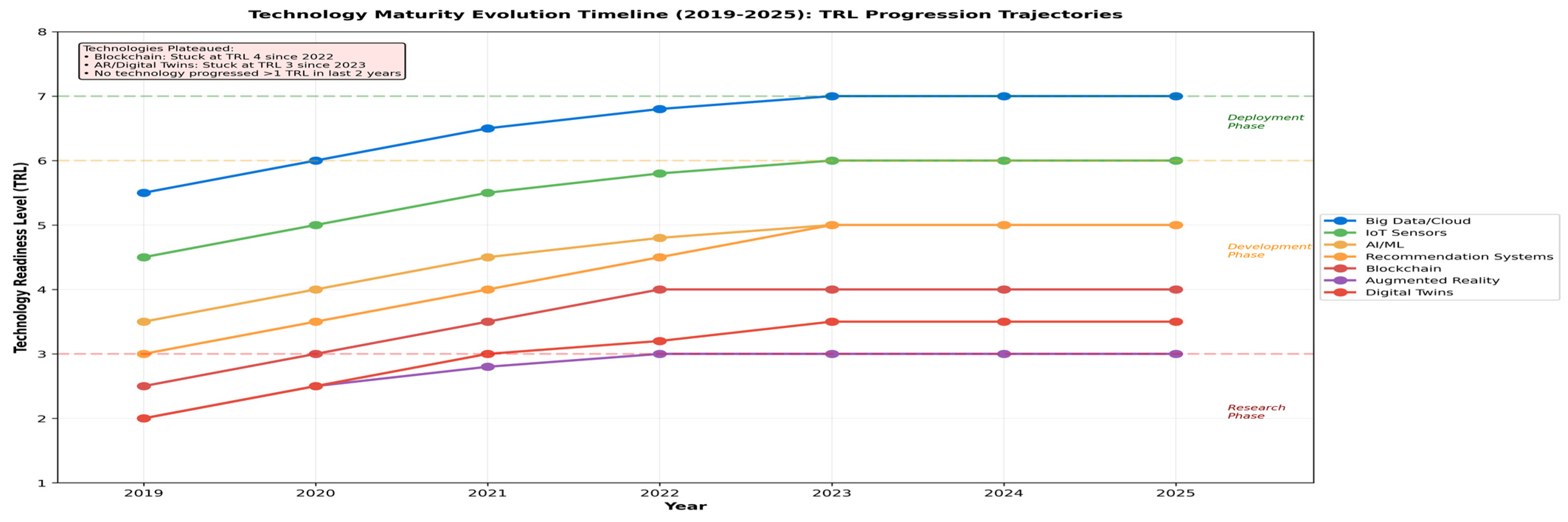

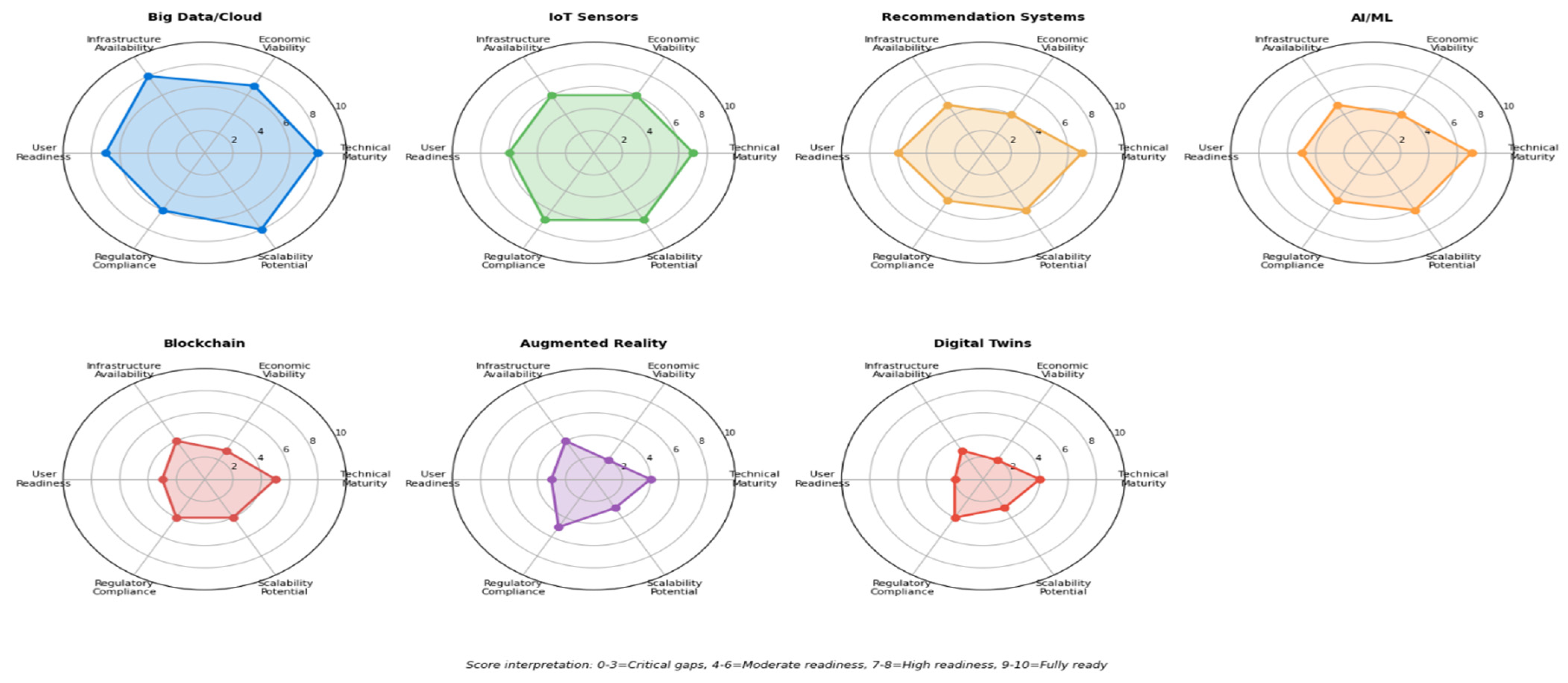

- To contextualize the NASA Technology Readiness Level (TRL) scale for agricultural market systems, we adopted a domain-specific adaptation reflecting the unique characteristics of agricultural deployment environments. While TRL 1–3 (conceptual and laboratory validation) remains unchanged, TRL 4–6 was operationalized to incorporate field pilot feasibility under environmental variability, supply chain infrastructure, and farmer adoption conditions. Specifically, TRL 4 corresponds to prototype validation in controlled agricultural settings (e.g., research farms); TRL 5 represents pilot implementation with real users under limited scale (<50 farmers or <6 months of use); and TRL 6 requires operational deployment in heterogeneous farming contexts with demonstrable continuity (>50 users and >6 months operation). TRL 7–9 was defined by increasing degrees of scalability, integration with market actors, and sustained multi-season adoption. This adaptation ensures that maturity assessments account not only for technical performance but also for real-world agricultural constraints such as infrastructure availability, climate variability, digital literacy, and value chain actor coordination.

- Implementation maturity was categorized into Prototype, Pilot, Operational Deployment, and Sustained Deployment based on deployment duration, user scale, and real-world usage evidence.

- Cross-tabulations were performed to evaluate relationships between technology type, performance reporting rigor, and maturity stage, highlighting the research-to-practice gap.

- Thematic coding was conducted using a hybrid inductive–deductive approach, where deductive codes were derived from the research questions and inductive codes emerged during iterative reading.

- Coding was performed manually using tag-matrix structures in Excel, rather than automated qualitative analysis software, due to the structured nature of reported statements.

- Barrier and opportunity statements were categorized into frequency groups (infrastructure, cost, literacy, interoperability, regulatory, data security, organizational readiness).

- Equity implications were assessed through content analysis of discussions referencing smallholder farmers, accessibility, affordability, and digital divide challenges.

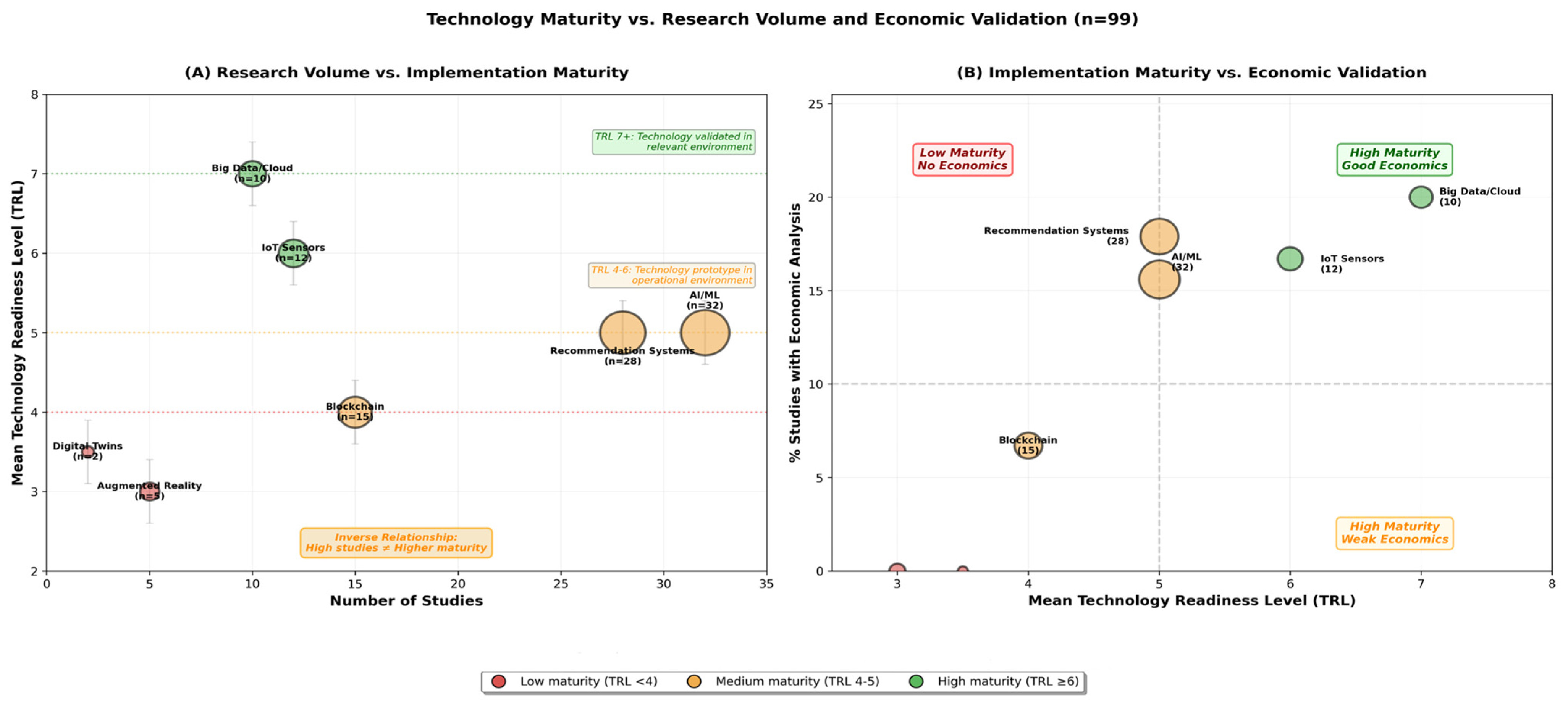

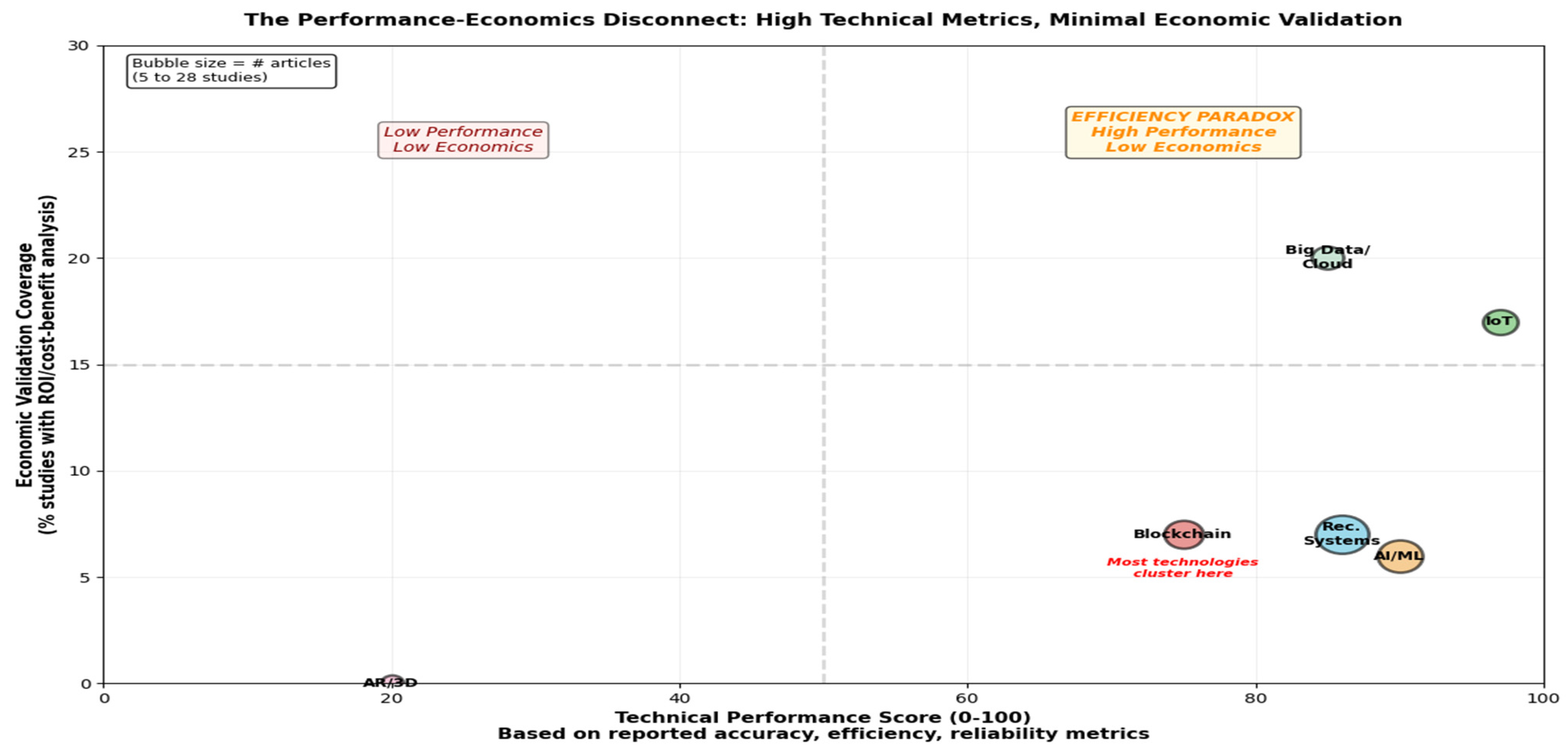

- A comparative matrix plotted TRL level vs. presence/absence of economic validation, operationalizing the “efficiency paradox”: high technical performance coupled with limited deployment viability.

- Thematic coding of limitations/discussions to identify barriers/opportunities; barrier frequency; assessment of equity and accessibility. Relationships among TRL, validation type, and economic evidence were explored with Pearson correlations and ANOVA. All plots were generated in A (matplotlib); no formal meta-analysis was attempted due to metric heterogeneity.

2.9. Limitations

- Publication bias: Systematic reviews reflect the published literature disproportionately reporting positive results. Failed implementations receive minimal documentation, potentially generating optimistic effectiveness assessments.

- Database restrictions: Limiting searches to Scopus, WoS, IEEE Xplore excludes gray literature and non-English publications, introducing potential geographic bias.

- Temporal window: The 2019–2025 timeframe prioritized recent developments but excludes earlier foundational work.

- Metric heterogeneity: Diverse performance metrics, evaluation contexts, and reporting standards precluded formal meta-analysis. Synthesis remained qualitative.

- Validation data scarcity: Only 31% of studies reported temporal/geographic generalization testing, limiting robust assessment of algorithm transferability.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Overview of Selected Studies

3.1.1. Temporal Distribution and Publication Trends

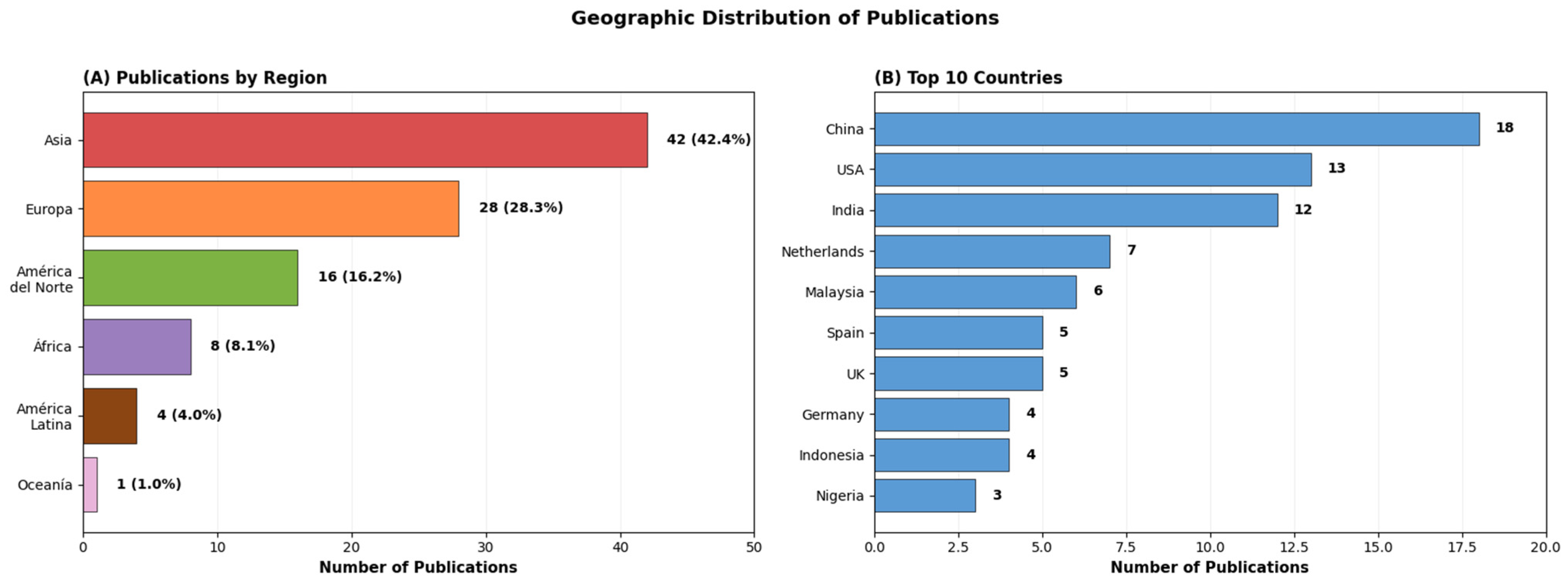

3.1.2. Geographic Distribution and Institutional Contributions

3.1.3. Journal Quality and Citation Impact

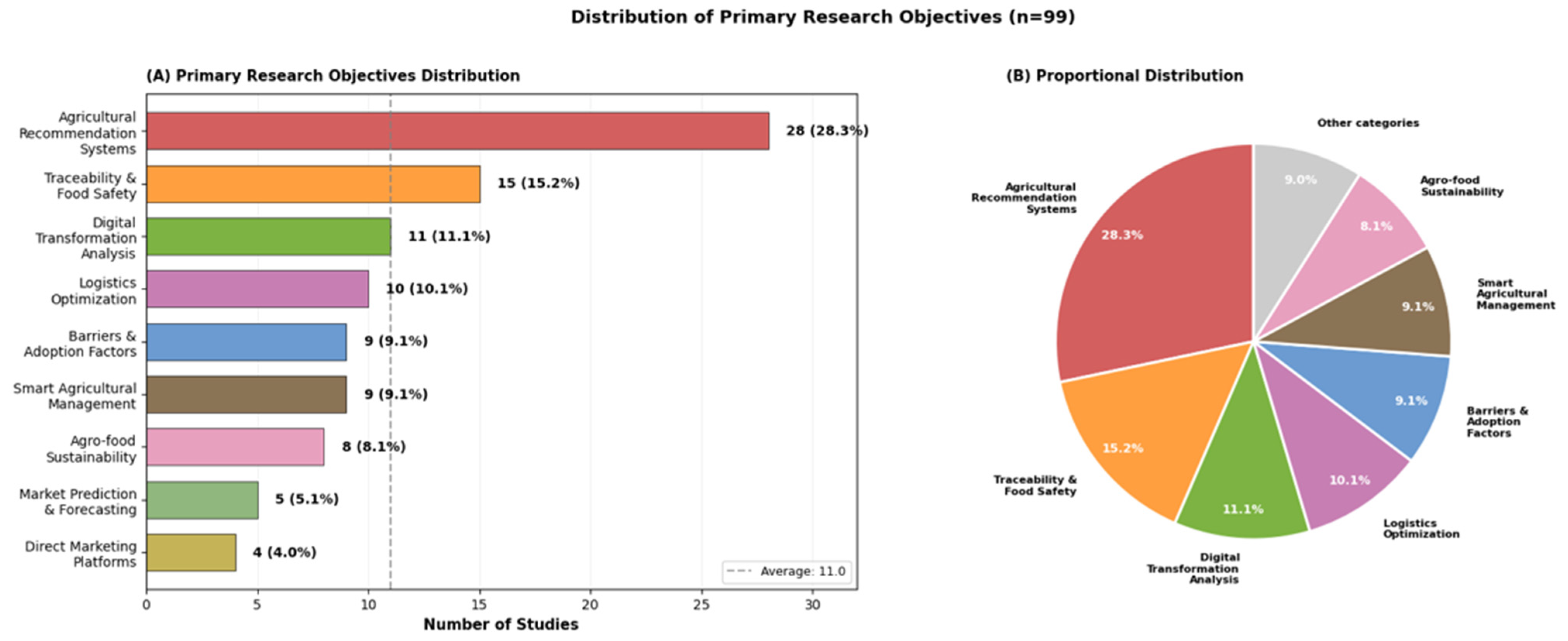

3.2. Research Focus and Thematic Analysis (RQ1)

3.2.1. Methodological Approaches

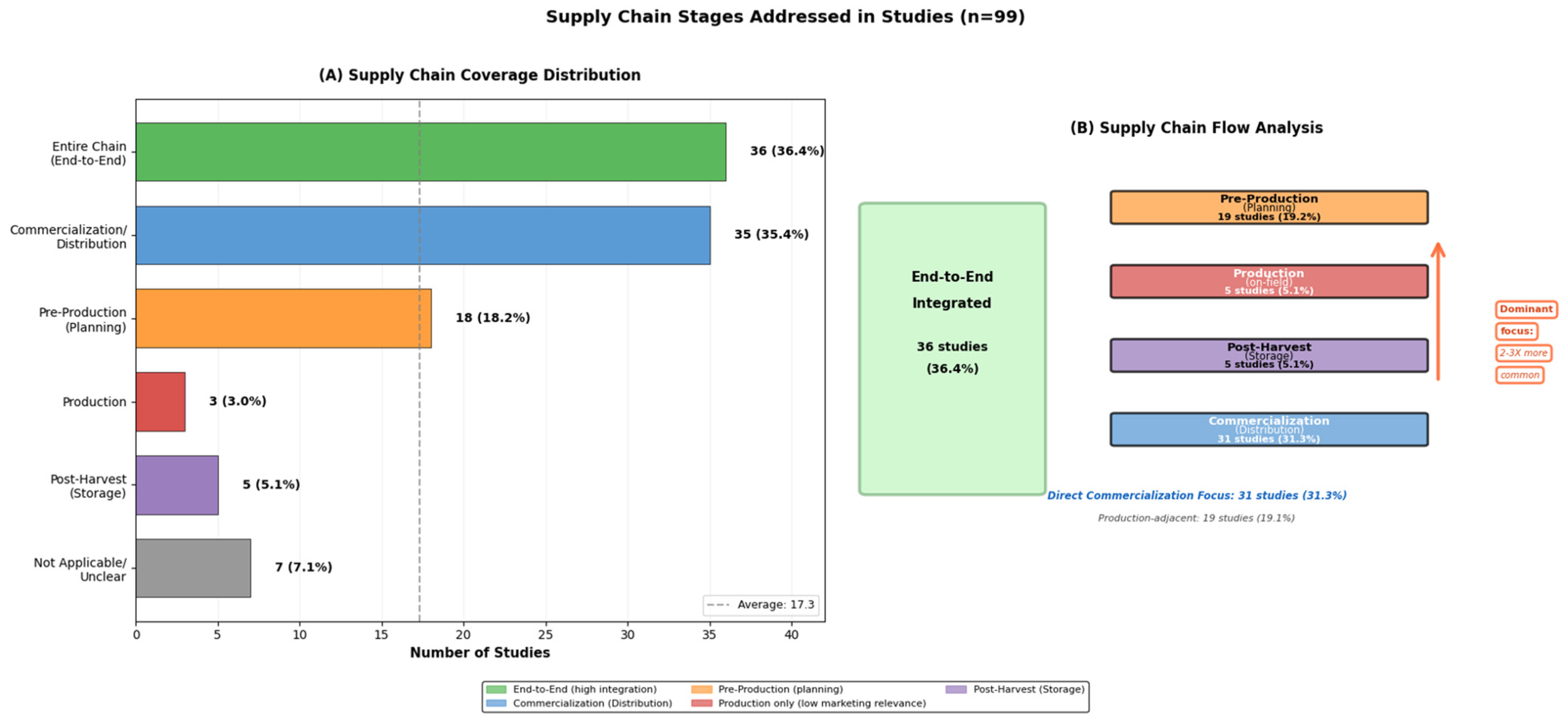

3.2.2. Supply Chain Stages Addressed

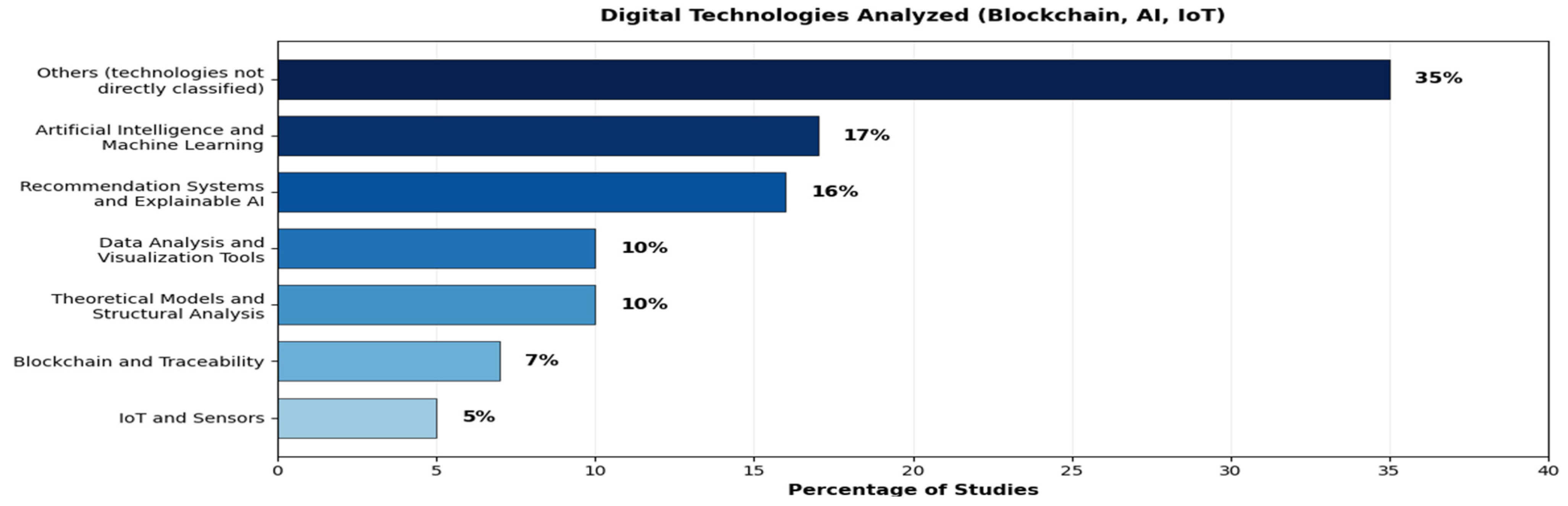

3.3. Technology Landscape and Applications (RQ1, RQ2)

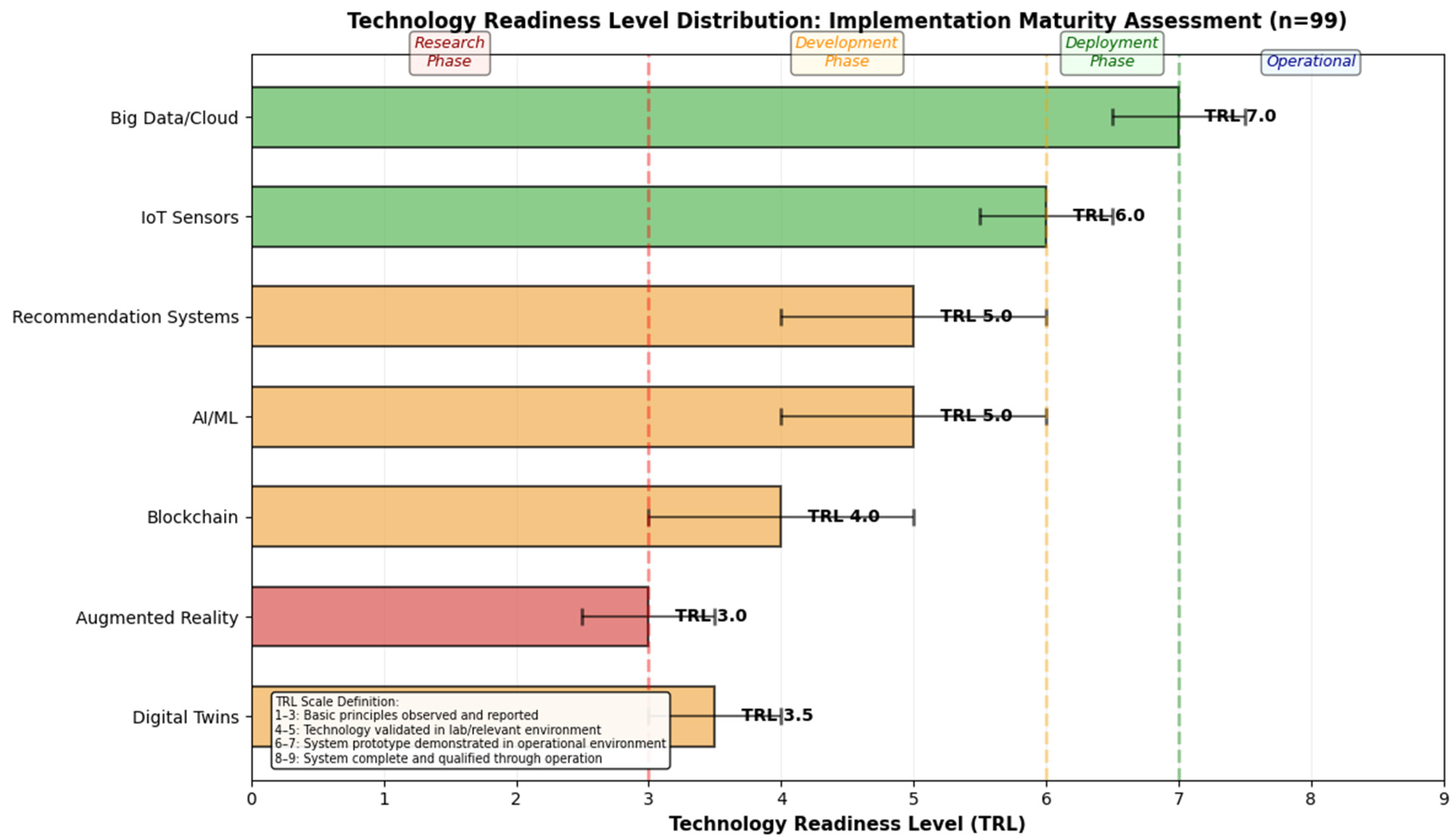

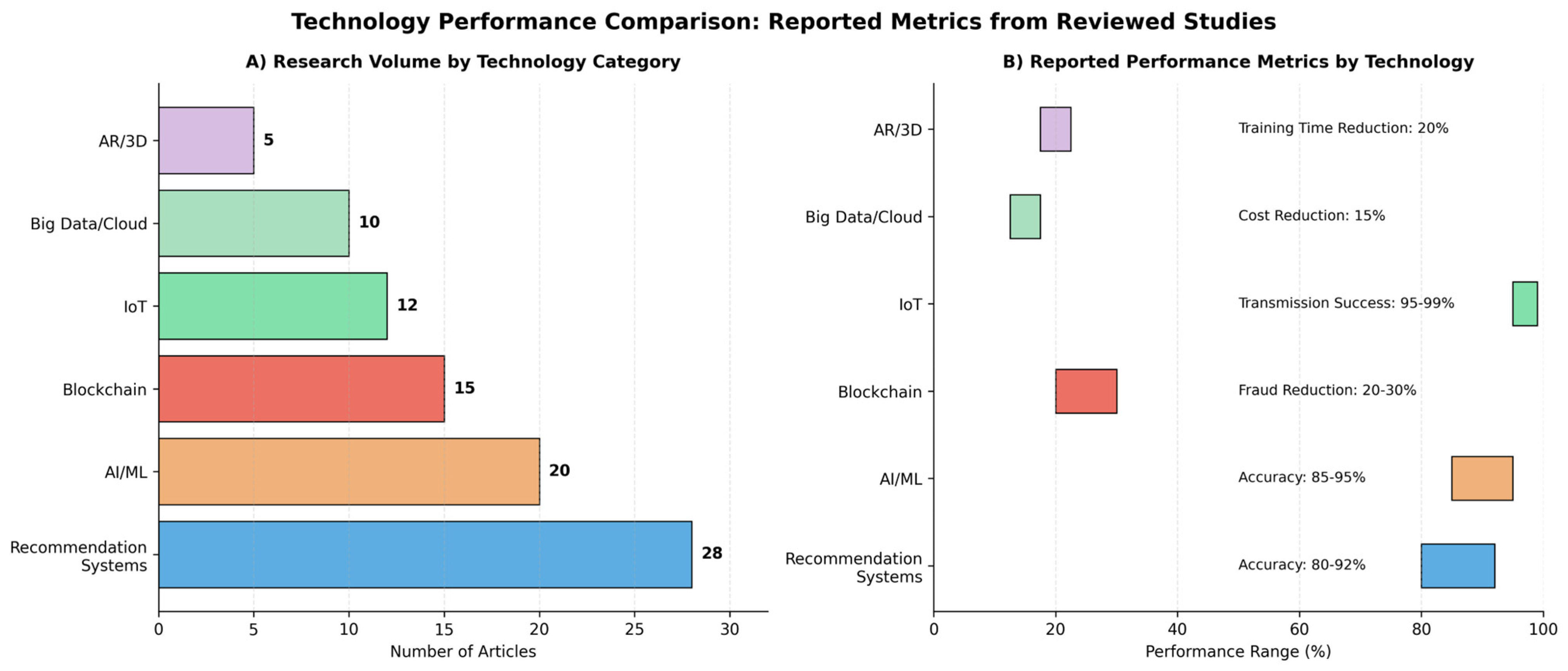

3.3.1. Technology Readiness Level and Research Volume

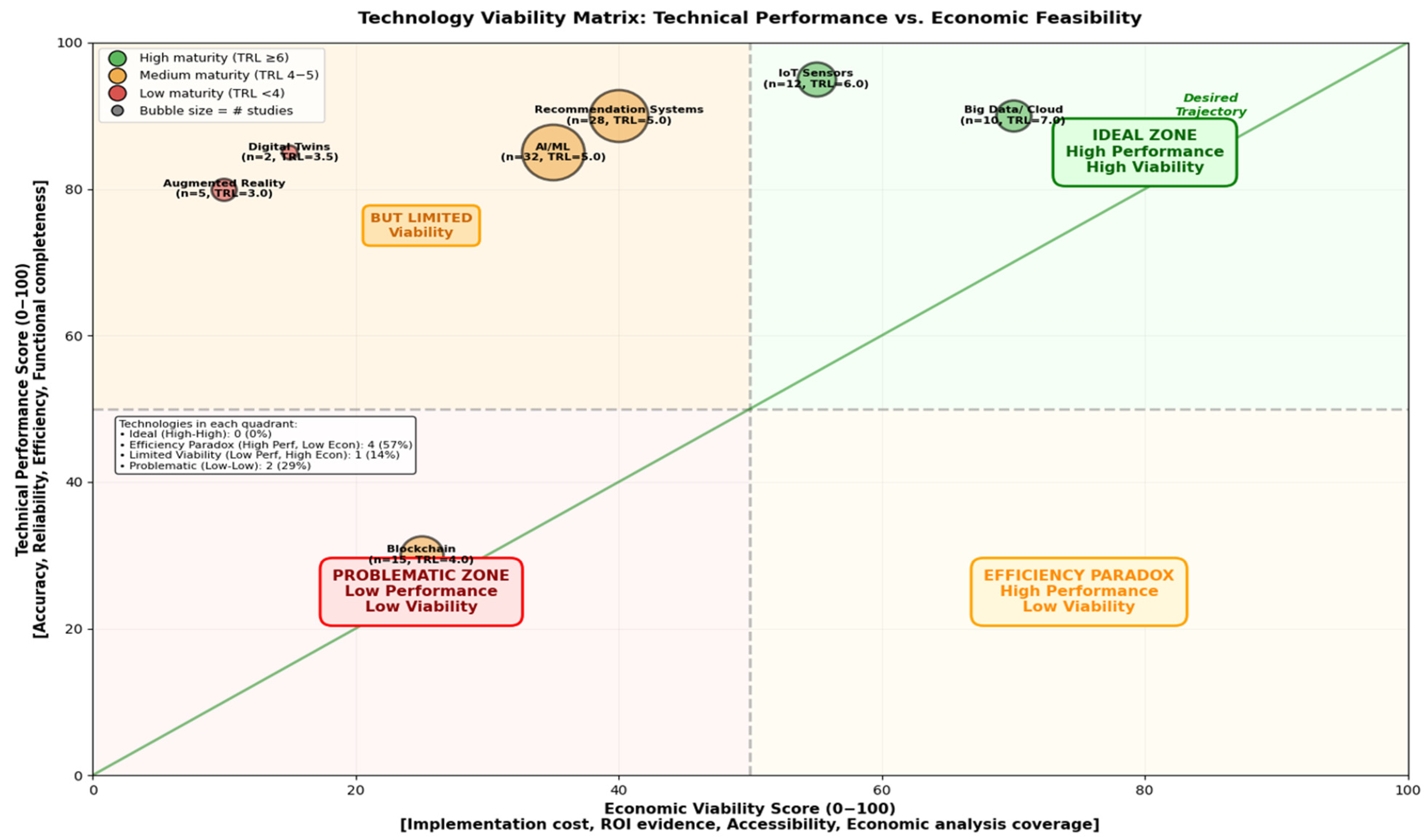

3.3.2. Technology Viability Assessment

Technology-Specific Profiles

Quadrant Distribution

3.4. Implementation Maturity and Technology Readiness (RQ3)

3.4.1. Technology Readiness Level Distribution: Implementation Maturity Assessment

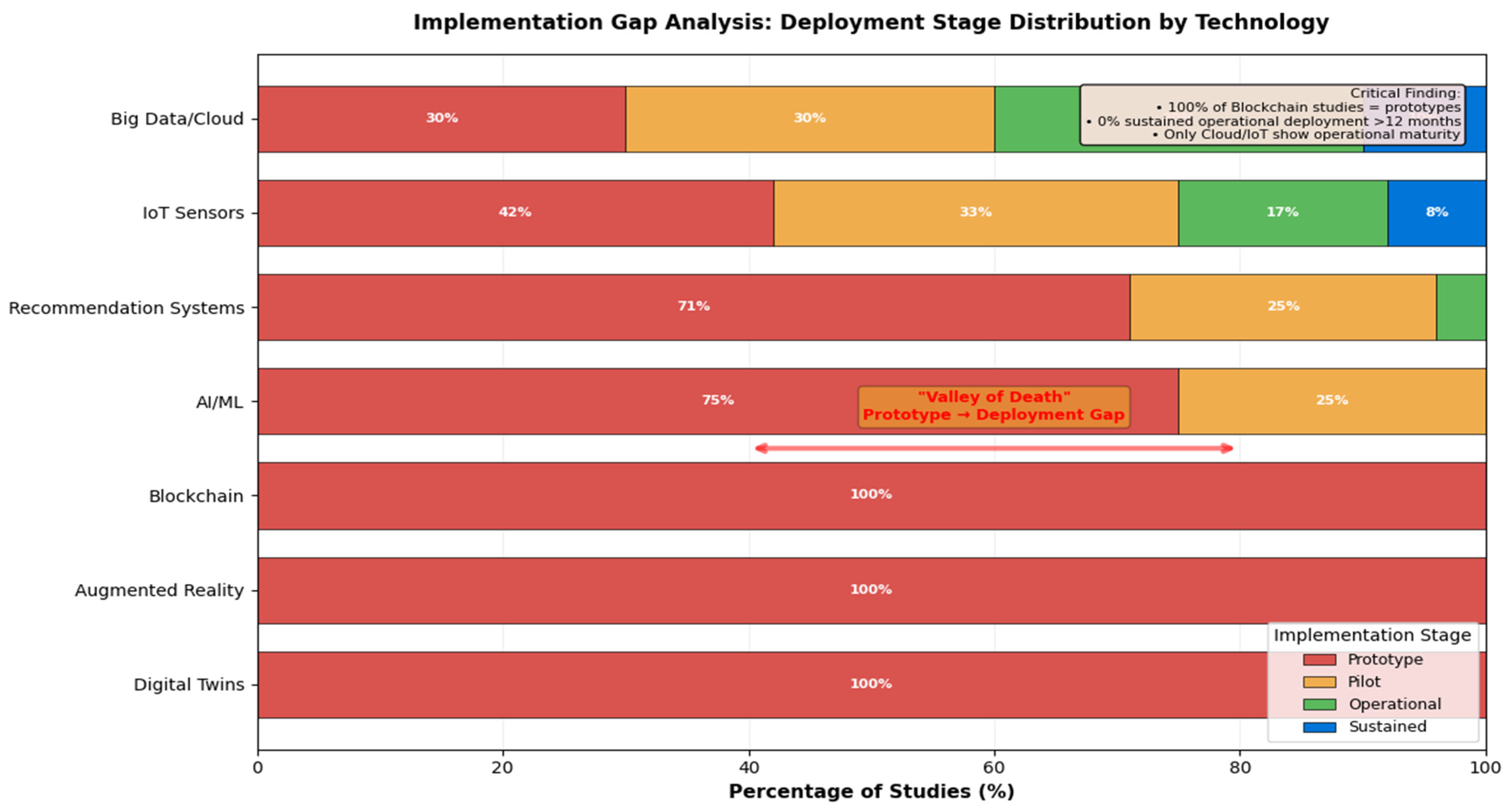

3.4.2. Implementation of Stage Distribution

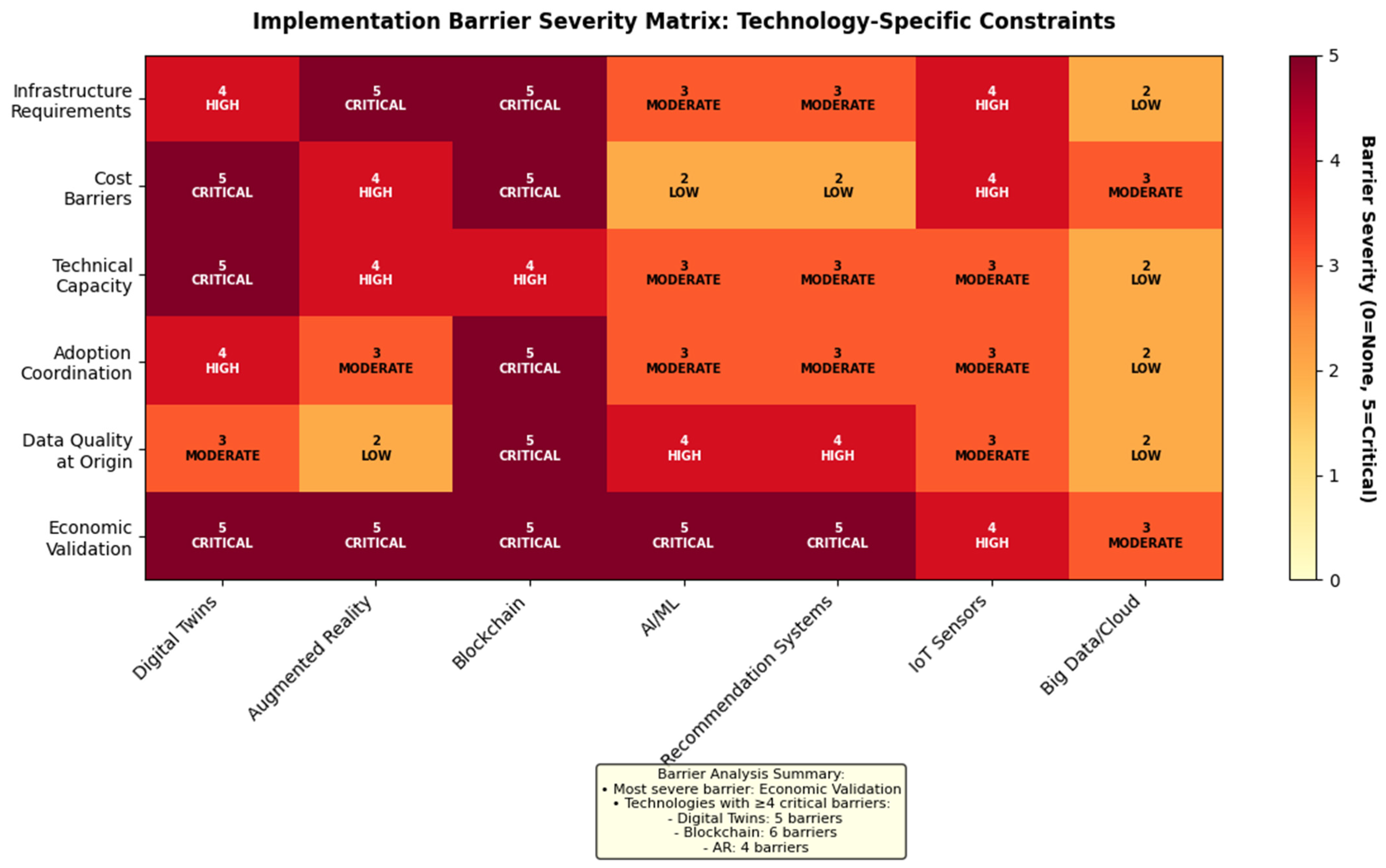

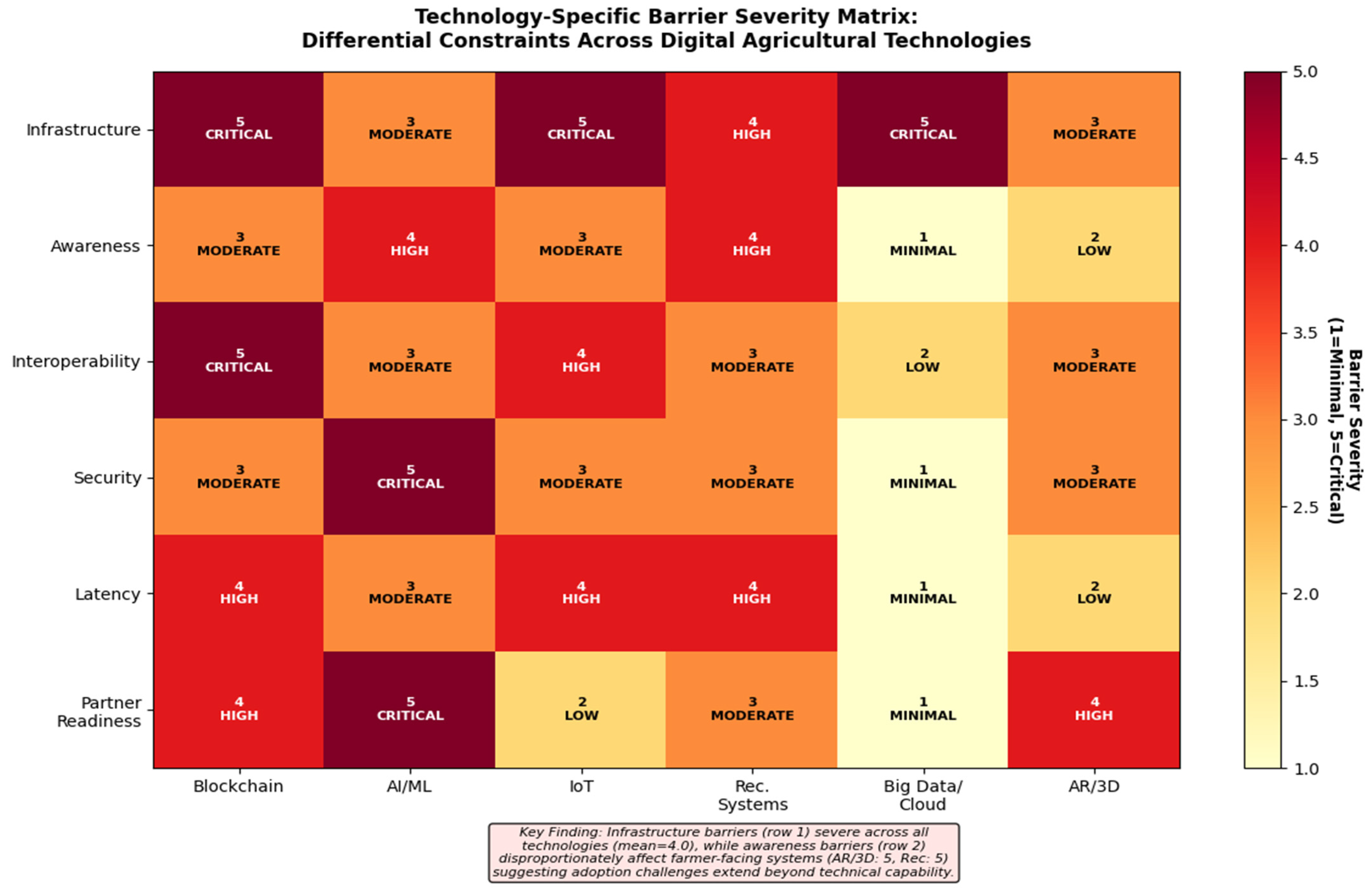

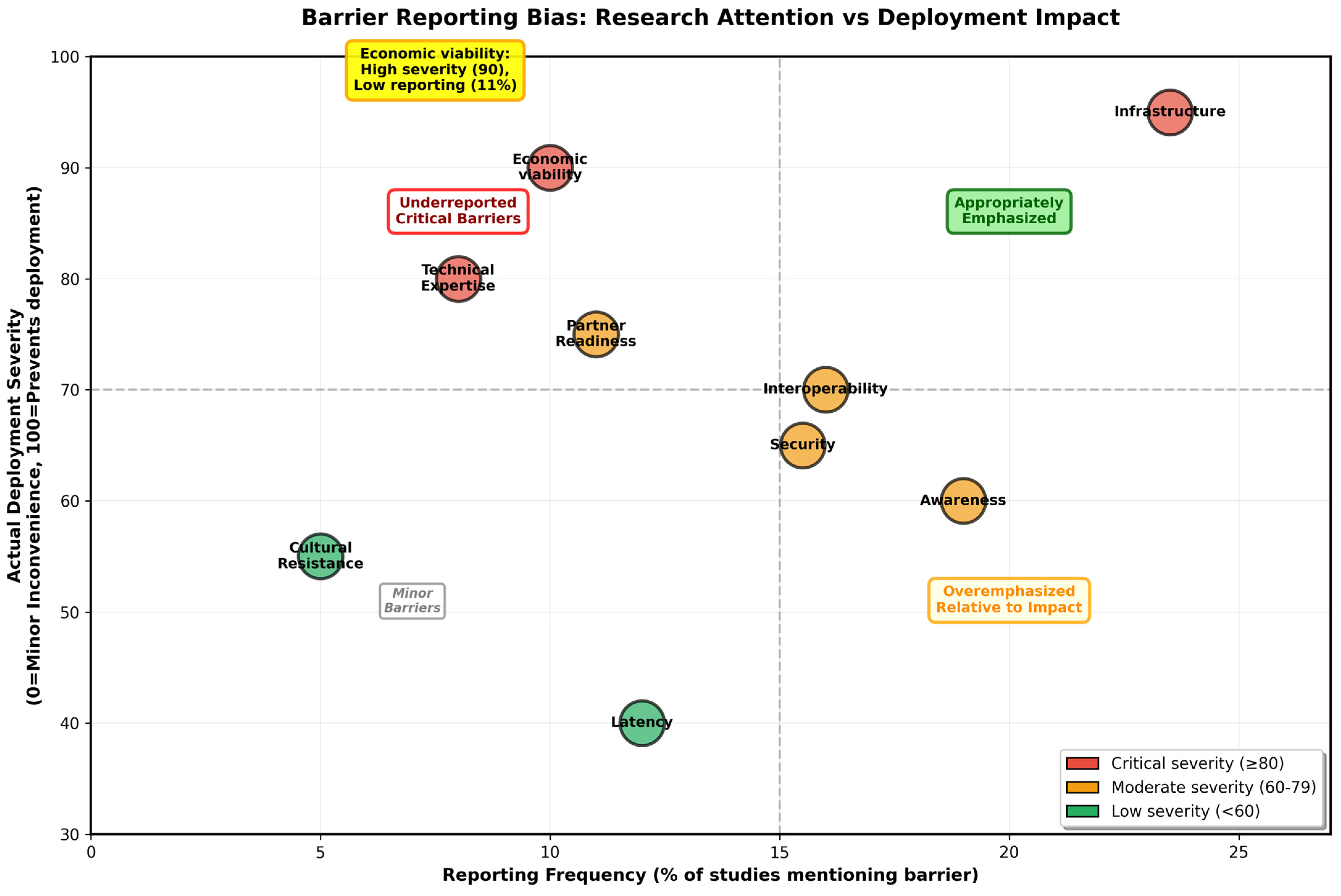

3.4.3. Implementation Barrier Severity

3.4.4. Technology Maturity Evolution Timeline (2019–2025): TRL Progression Trajectories

3.4.5. Multi-Dimensional Deployment Readiness

3.5. Evaluation of Methodology and Performance Metrics (RQ2)

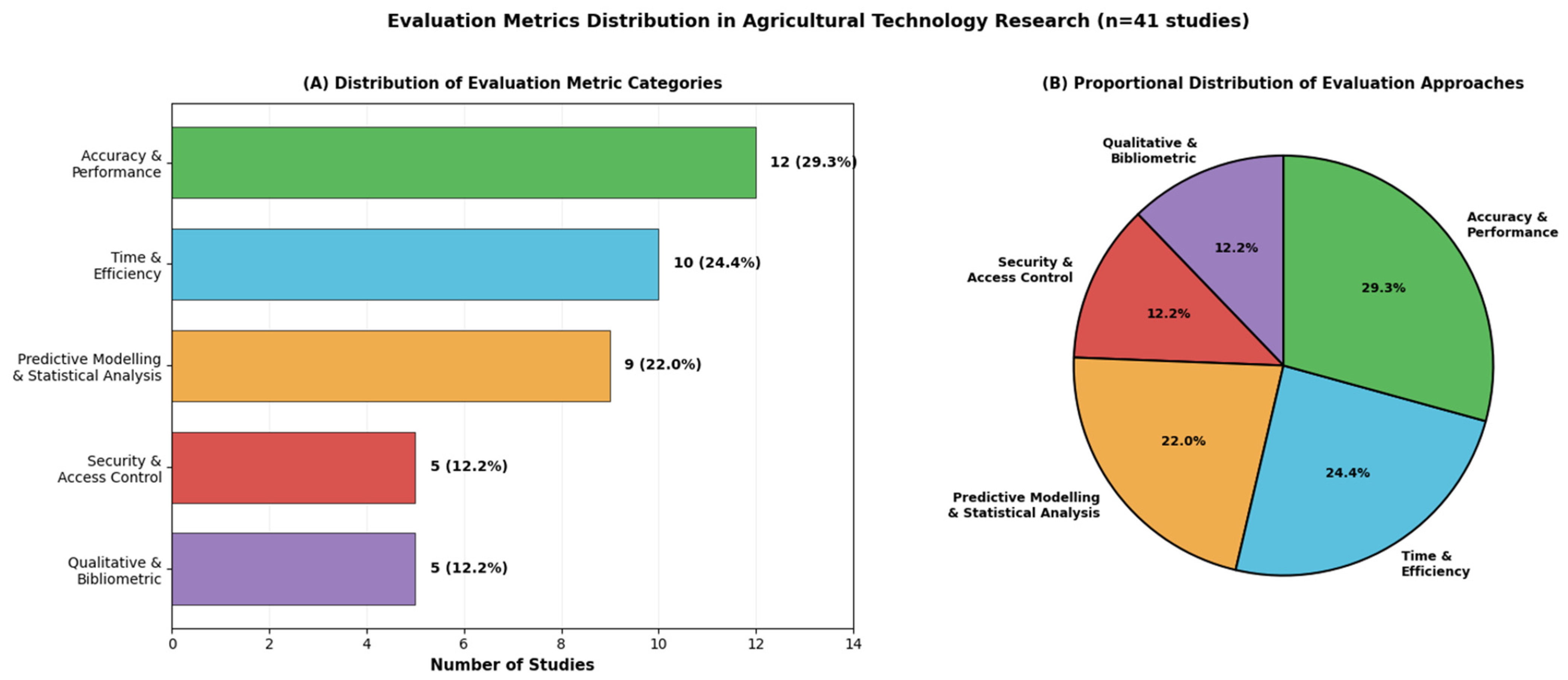

3.5.1. Evaluation Metric Distribution

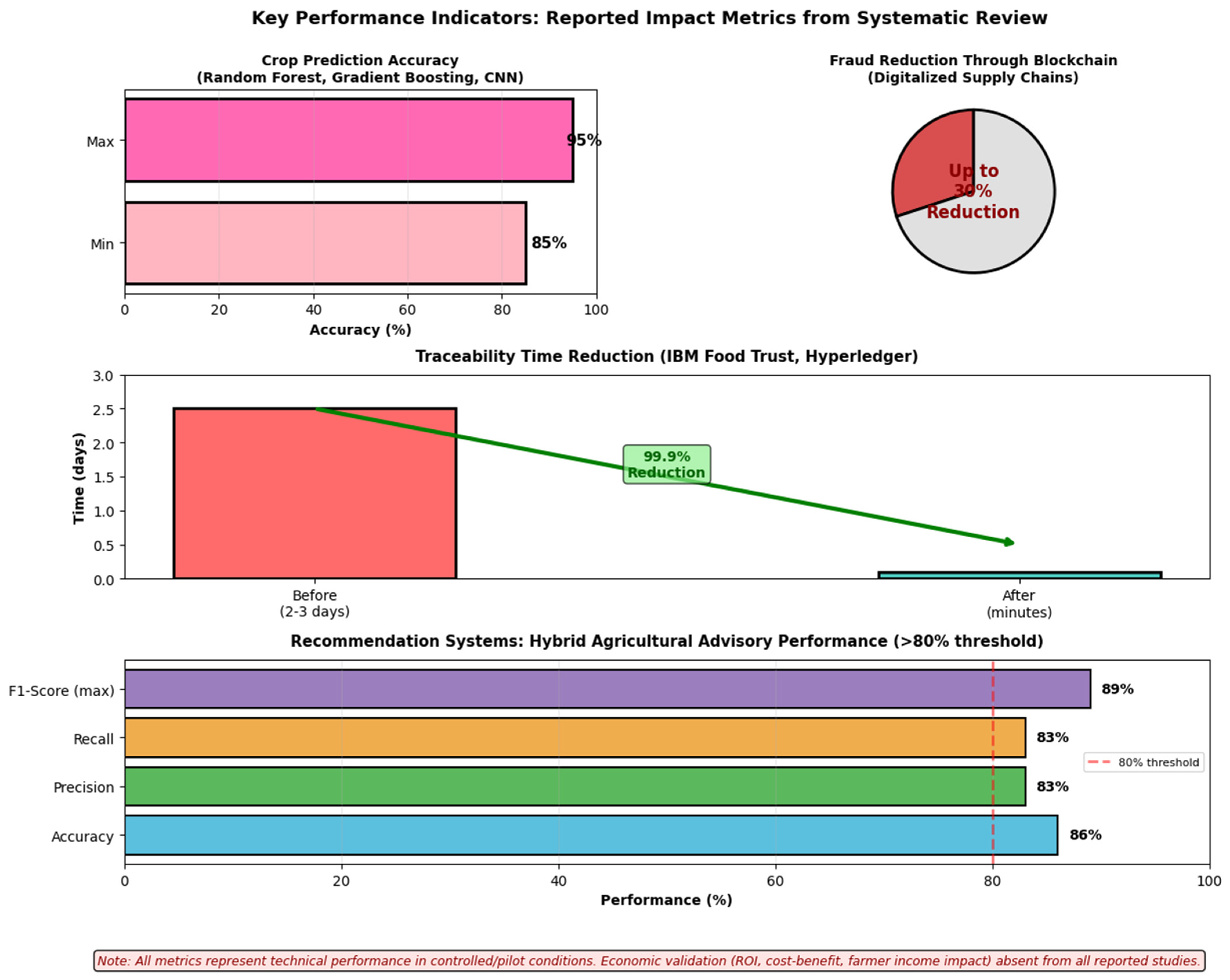

3.5.2. Comparative Technology Performance

3.5.3. Key Performance Indicators

3.5.4. Evaluation Gaps

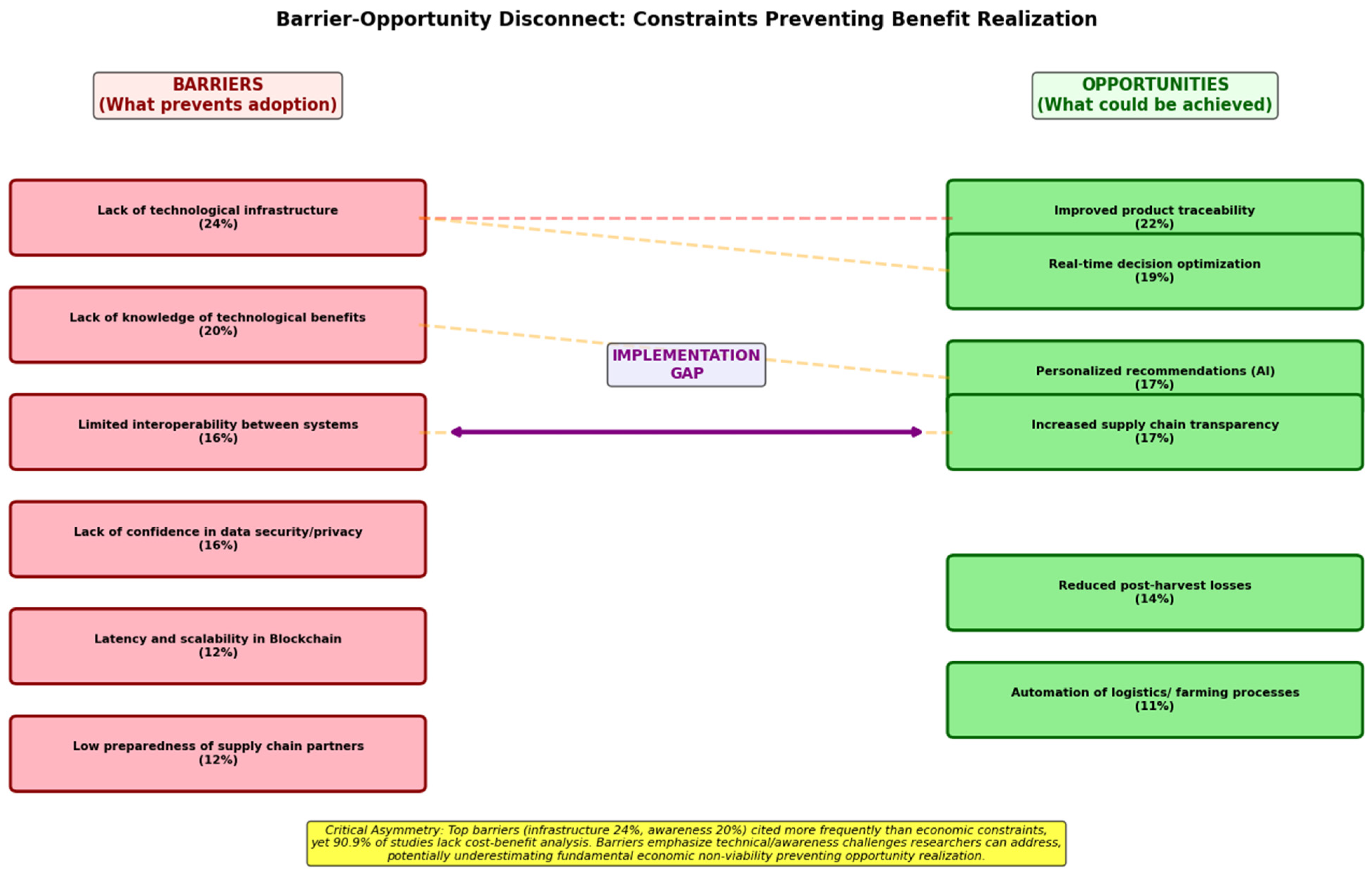

3.6. Implementation Barriers and Adoption Opportunities (RQ4)

3.6.1. Barrier Frequency and Technology-Specific Severity

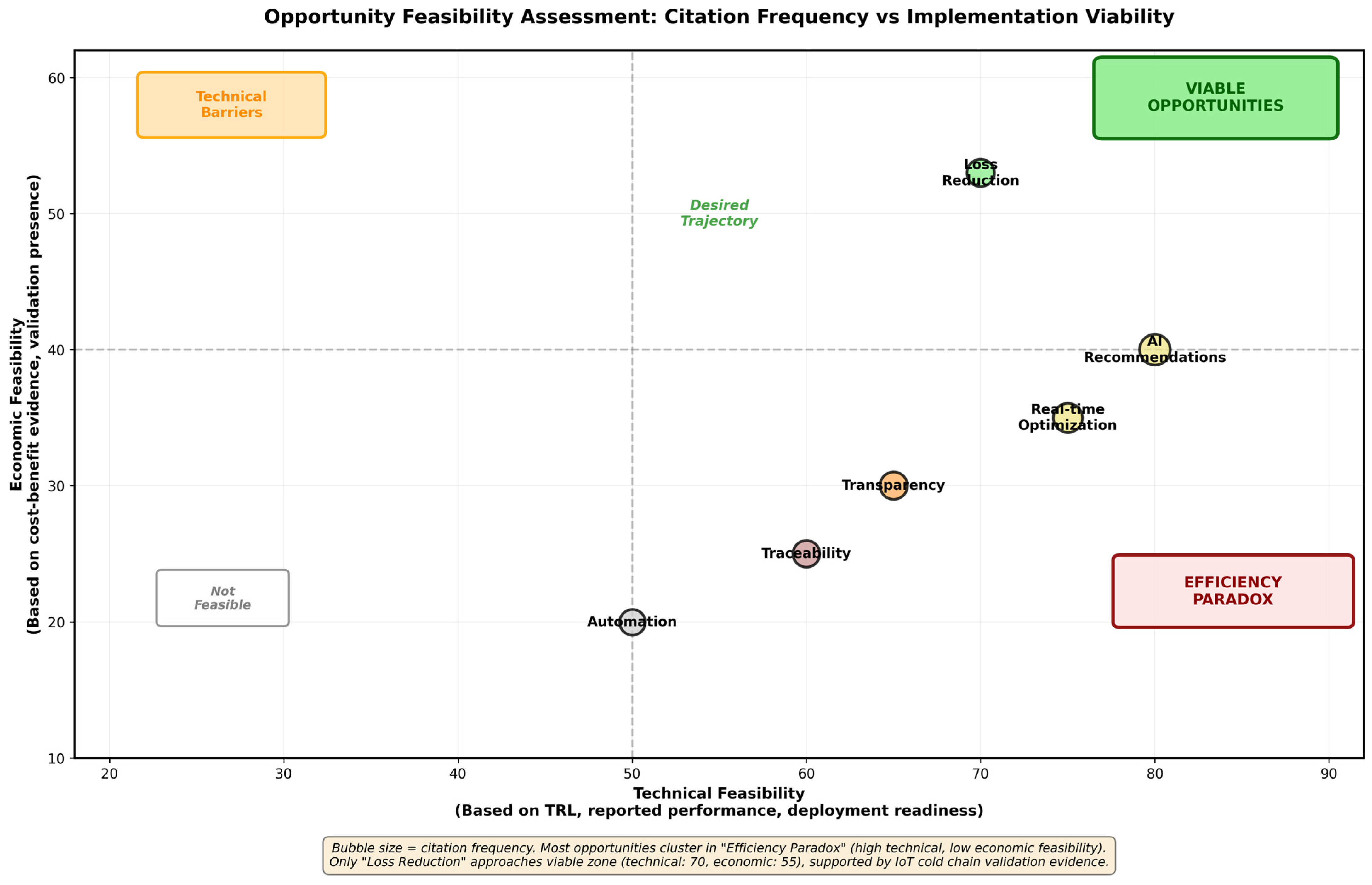

3.6.2. Opportunity Citation Frequency

3.6.3. Barrier Reporting Patterns

3.6.4. Opportunity Feasibility Distribution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Key Contributions

5.2. Implications for Computational Research

5.3. Critical Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Composite Score Construction Method

References

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; Van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, C.B. Agricultural markets and development. In Annual Review of Resource Economics; Annual Reviews: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2021; Volume 13, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, T.; Echeverria, R.; Berdegué, J.; Minten, B.; Liverpool-Tasie, S.; Tschirley, D.; Zilberman, D. Rapid transformation of food systems in developing regions: Highlighting the role of agricultural research & innovations. Agric. Syst. 2019, 172, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, A.W. Understanding Agricultural Marketing. Food and Agriculture; Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vorley, B. Food, Inc. Corporate Concentration from Farm to Consumer; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED): London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Poulton, C.; Dorward, A.; Kydd, J. The future of small farms: New directions for services, institutions, and intermediation. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1413–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Wheeler, R.; Winter, M.; Lobley, M.; Chivers, C.A. Agriculture 4.0: Making it work for people, production, and the planet. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfert, S.; Ge, L.; Verdouw, C.; Bogaardt, M.J. Big Data in Smart Farming—A review. Agric. Syst. 2017, 153, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz-Rubio, V.; Rovira-Más, F. From Smart Farming towards Agriculture 5.0: A Review on Crop Data Management. Agronomy 2020, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacco, M.; Barsocchi, P.; Ferro, E.; Gotta, A.; Ruggeri, M. The digitisation of agriculture: A survey of research activities on smart farming. Array 2019, 3, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Jakku, E.; Labarthe, P. A review of social science on digital agriculture, smart farming and agriculture 4.0: New contributions and a future research agenda. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, A.; Fonts, A.; Prenafeta-Boldύ, F.X. The rise of blockchain technology in agriculture and food supply chains. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F. A supply chain traceability system for food safety based on HACCP, blockchain & Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Service Systems and Service Management, Dalian, China, 16–18 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Verdouw, C.; Tekinerdogan, B.; Beulens, A.; Wolfert, S. Digital twins in smart farming. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Dong, H. Application of Intelligent Recommendation for Agricultural Information: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 153616–153632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Evert, F.K.; Fountas, S.; Jakovetic, D.; Crnojevic, V.; Travlos, I.; Kempenaar, C. Big Data for weed control and crop protection. Weed Res. 2017, 57, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, D.I.; Rieder, R. Computer vision and artificial intelligence in precision agriculture for grain crops: A systematic review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 153, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielke, S.; Taylor, B.; Jakku, E. Digitalisation of agricultural knowledge and advice networks: A state-of-the-art review. Agric. Syst. 2020, 180, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine learning in agriculture: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraka, R.E.; Chen, R.C.; Toharudin, T.; Gio, P.U.; Pardamean, B. How big data and machine learning impact agriculture. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- C. A. S. P. (CASP). CASP Qualitative Checklist. Available, 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Baas, J.; Schotten, M.; Plume, A.; Côté, G.; Karimi, R. Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkle, C.; Pendlebury, D.A.; Schnell, J.; Adams, J. Web of Science as a data source for research on scientific and scholarly activity. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE. IEEE Xplore Digital Library 2024. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annane, B.; Alti, A.; Lakehal, A. A Blockchain Semantic-based Approach for Secure and Traceable Agri-Food Supply Chain. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 18131–18137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Albarrak, A.S. A Blockchain-Driven Food Supply Chain Management Using QR Code and XAI-Faster RCNN Architecture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilakarathne, N.N.; Bakar, M.S.A.; Abas, P.E.; Yassin, H. A Cloud Enabled Crop Recommendation Platform for Machine Learning-Driven Precision Farming. Sensors 2022, 22, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, A.V.; Patil, D.D.; Tripathi, K.K. A Comprehensive Survey on Recommender Systems Techniques and Challenges in Big Data Analytics with IOT Applications. Rev. Gestão Soc. Ambient. 2024, 18, e05195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rslan, E.; Khafagy, M.H.; Ali, M.; Munir, K.; Badry, R.M. AgroSupportAnalytics: Big data recommender system for agricultural farmer complaints in Egypt. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2023, 13, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamatchi, S.B.; Parvathi, R. Improvement of Crop Production Using Recommender System by Weather Forecasts. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 165, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhola, A.; Kumar, P. ML-CSFR: A Unified Crop Selection and Fertilizer Recommendation Framework based on Machine Learning. Scalable Comput. Pr. Exp. 2024, 25, 4111–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiruthika, S.; Karthika, D. IOT-BASED professional crop recommendation system using a weight-based long-term memory approach. Meas. Sens. 2023, 27, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouni, M.; Hssina, B.; Douzi, K.; Douzi, S. Towards an Efficient Recommender Systems in Smart Agriculture: A deep reinforcement learning approach. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 203, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paithane, P.M. Random forest algorithm use for crop recommendation. J. Eng. Technol. Ind. Appl. 2023, 9, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hua, S. Recommendation of Business Models for Agriculture-Related Platforms Based on Deep Learning. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 7330078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyaz, Z.; Ebrahimian, M.; Nawara, D.; Ibrahim, A.; Kashef, R. Recommendation systems: Algorithms, challenges, metrics, and business opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guixia, X.; Samian, N.; Faizal, M.F.M.; As’ad, M.A.Z.M.; Fadzil, M.F.M.; Abdullah, A.; Seah, W.K.G.; Ishak, M.; Hermadi, I. A Framework for Blockchain and Internet of Things Integration in Improving Food Security in the Food Supply Chain. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 34, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagias, E.P.; Gayialis, S.P.; Papadopoulos, G.A.; Papoutsis, G. An Ethereum-Based Distributed Application for Enhancing Food Supply Chain Traceability. Foods 2023, 12, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Gao, Q.; Wu, H.; Liu, N. Carbon-Efficient Scheduling in Fresh Food Supply Chains with a Time-Window-Constrained Deep Reinforcement Learning Model. Sensors 2024, 24, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saban, M.; Bekkour, M.; Amdaouch, I.; El Gueri, J.; Ahmed, B.A.; Chaari, M.Z.; Ruiz-Alzola, J.; Rosado-Muñoz, A.; Aghzout, O. A Smart Agricultural System Based on PLC and a Cloud Computing Web Application Using LoRa and LoRaWan. Sensors 2023, 23, 2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilhabel, S.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Basu, C.; Madan, M.; Glennan, C.; McSherry, L. Blockchain technology in the food supply chain: Influences on supplier relationships and outcomes. Issues Inf. Syst. 2023, 24., 321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Han, X.; Zhou, B.; Wang, W. Assessing the adoption barriers for AI in food supply chain finance applying a hybrid interval-valued Fermatean fuzzy CRITIC-ARAS model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umami, I.; Rahmawati, L. Comparing Epsilon Greedy and Thompson Sampling model for Multi-Armed Bandit algorithm on Marketing Dataset. J. Appl. Data Sci. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R.; Duan, Y.; Ajmal, T.; Pelc, K.; Gillespie, J.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Condell, J.; Hermens, I.; Ramanathan, U. Motivations and Challenges for Food Companies in Using IoT Sensors for Reducing Food Waste: Some Insights and a Road Map for the Future. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qin, X.; Zheng, H. Research on Contextual Recommendation System of Agricultural Science and Technology Resource Based on User Portrait. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1693, 012186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandan, A.; John, M.; Potdar, V. Achieving UN SDGs in Food Supply Chain Using Blockchain Technology. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Guo, Y.; Mu, Q.; Wang, S. Advances in Machine Learning and Hyperspectral Imaging in the Food Supply Chain. Food Eng. Rev. 2022, 14, 596–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, P.; Genge, B. Efficient Behavior Prediction Based on User Events. J. Commun. Softw. Syst. 2021, 17, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmond, A.B.; Hidayat, F.; Supangkat, S.H. Electronic Commerce Product Recommendation using Enhanced Conjoint Analysis. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. (IJACSA) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toader, D.-C.; Rădulescu, C.M.; Toader, C. Investigating the Adoption of Blockchain Technology in Agri-Food Supply Chains: Analysis of an Extended UTAUT Model. Agriculture 2024, 14, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, M.C.; Saravanan, P. Crop Insurance Premium Recommendation System Using Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2023, 8, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Patidar, S.; Sukhwani, V.K.; Shukla, A.C. Modeling of Critical Food Supply Chain Drivers Using DEMATEL Method and Blockchain Technology. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. C 2023, 104, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbadlisa, G.; Jokonya, O. Factors Affecting the Adoption of Blockchain Technologies in the Food Supply Chain. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1497599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, N.; Kaswan, K.S. Machine Learning Approach for Prediction of the Online User Intention for a Product PurchaseMachine Learning Approach for Prediction of the Online User Intention for a Product Purchase. Int. J. Recent Innov. Trends Comput. Commun. 2023, 11, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Ge, H.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ji, X.; Jia, Z.; Cui, G. A Blockchain-Based Traceability Model for Grain and Oil Food Supply Chain. Foods 2023, 12, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Han, J.; Qi, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, K.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, X. A Reliable Traceability Model for Grain and Oil Quality Safety Based on Blockchain and Industrial Internet. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, W.; Al-Ansari, T. GM-Ledger: Blockchain-Based Certificate Authentication for International Food Trade. Foods 2023, 12, 3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Kamaruddin, N.S.; Wang, D. Huang, Integration and Analysis of Data in Grain Quality and Safety Traceability Using Blockchain Technology. J. Logist. Inform. Serv. Sci. 2023, 10, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Astuti, R.; Hidayati, L. How might blockchain technology be used in the food supply chain? A systematic literature review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2246739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; Casagranda, L.F.; Butturi, M.A.; Sellitto, M.A. Digital Technologies, Sustainability, and Efficiency in Grain Post-Harvest Activities: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mendes, S.; Alonso-Muñoz, S.; García-Muiña, F.E.; González-Sánchez, R. Discovering the conceptual building blocks of blockchain technology applications in the agri-food supply chain: A review and re-search agenda. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 182–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastidar, U.G.; Ambekar, S.S.; Hudnurkar, M.; Lidbe, A.D. Experiential Retailing Leveraged by Data Analytics. Int. J. Bus. Intell. Res. 2021, 12, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Potdar, V.; Quaddus, M. Exploring Factors and Impact of Blockchain Technology in the Food Supply Chains: An Exploratory Study. Foods 2023, 12, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz-Flores, J.C.; Aguado-Rodriguez, R.J.; Zegarra-Aguinaga, E.A.; Collao-Diaz, M.F.; Flores-Perez, A.E. Industry 4.0, Circular Economy and Sustainability in the Food Industry: A Literature Review. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Oper. Manag. 2023, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.; Mikiciuk, G.; Durlik, I.; Mikiciuk, M.; Łobodzińska, A.; Śnieg, M. The IoT and AI in Agriculture: The Time Is Now—A Systematic Review of Smart Sensing Technologies. Sensors 2025, 25, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demestichas, K.; Peppes, N.; Alexakis, T.; Adamopoulou, E. Blockchain in Agriculture Traceability Systems: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendros, A.; Drosatos, G.; Efraimidis, P.S.; Tsirliganis, N.C. Blockchain Applications in Agriculture: A Scoping Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Region | No. of Studies | Percentage | Leading Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 57 | 57.6% | India (28), China (12), Malaysia (4), Indonesia (3), Pakistan (2), Saudi Arabia (2) |

| Europe | 17 | 17.2% | UK (5), Spain (3), Italy (3), Romania (2), Greece (1), Serbia (1), Ireland (1), Lithuania (1) |

| Africa | 14 | 14.1% | South Africa (3), Morocco (2), Egypt (2), Somalia (2), Nigeria (1), Algeria (1), Ethiopia (1), Kenya (1), Mali (1) |

| North America | 5 | 5.1% | USA (5) |

| Latin America | 5 | 5.1% | Peru (2), Brazil (1), Chile (1), Colombia (1) |

| Oceania | 1 | 1.0% | Australia (1) |

| Journal | No. of Articles | SJR Quartile | H-Index | Focus Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability (MDPI) | 12 | Q2 | 97 | Sustainability science, multidisciplinary |

| IEEE Access | 8 | Q2 | 127 | Computer science, engineering |

| Sensors (MDPI) | 6 | Q1 | 145 | Sensor technology, IoT |

| Agricultural Systems | 5 | Q1 | 115 | Agricultural sciences, systems |

| Computers and Electronics in Agriculture | 5 | Q1 | 127 | Agricultural technology, informatics |

| Foods (MDPI) | 4 | Q1 | 76 | Food science, supply chain |

| Applied Sciences (MDPI) | 4 | Q2 | 73 | Applied sciences, multidisciplinary |

| Information | 3 | Q2 | 65 | Information science |

| Agriculture (MDPI) | 3 | Q2 | 59 | Agricultural sciences |

| Blockchain: Research and Applications | 3 | Q1 | 28 | Blockchain technology (new journal) |

| Journal of Physics: Conference Series | 3 | Q3 | 88 | Conference proceedings |

| Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems | 3 | Q2 | 42 | Food systems, sustainability |

| Scientific Reports | 2 | Q1 | 200 | Multidisciplinary sciences |

| International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications | 2 | Q3 | 51 | Computer science |

| Other journals (1 article each) | 36 | Various | - | - |

| Categories | Metrics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy and Performance | Fraud detection accuracy | [27] |

| Accuracy (99.53%) | [28] | |

| Accuracy, Recall, F1-score and K-Fold cross validation | [29] | |

| Accuracy, Recall, MAE, RMSE | [30] | |

| Accuracy, Recall, F1-score, accuracy, RMSE, MAE and NMAE | [31] | |

| Precision, recall and prediction error | [32] | |

| Accuracy, recall, F1-score, AUC | [33] | |

| Accuracy (95%), recall and run time | [34] | |

| Model accuracy and correct classification rate | [35] | |

| Model accuracy, achieving 99.09% accuracy with Random Forest | [36] | |

| Accuracy (P), recall (R) and F1-score | [37] | |

| Accuracy (99.2% with Decision Trees), recall, F1-score | [38] | |

| Time and Efficiency | Reduced search time (~7.5× faster than traditional methods) | [27] |

| Latency, transaction rate, throughput, scalability, and interoperability | [39] | |

| Reduced traceability time, data accuracy, and reliability | [40] | |

| Efficiency in reducing carbon emissions, reduced logistics costs | [41] | |

| Evaluation of packet loss, transmission latency, LoRa communication quality | [42] | |

| Product traceability times in the supply chain, food fraud reduction | [43] | |

| Barrier significance assessment based on interdependent criteria | [44] | |

| Overall performance and statistical significance | [45] | |

| Food waste reduction | [46] | |

| Safety, scalability, consensus efficiency | [47] | |

| Predictive Modelling and Statistical Analysis | Regression coefficient | [48] |

| R2, RMSE, SEP, CCR | [49] | |

| Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | [50] | |

| Relative Error, Correlation, RMSE | [51] | |

| Coefficient of Determination (R2) | [52] | |

| Gradient Boosting Regressor with an accuracy of 93.58%. | [53] | |

| Interrelation analysis using GTMA | [54] | |

| Frequency analysis and ANOVA | [55] | |

| Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD), Mean Magnitude of Relative Error (MMRE) | [56] | |

| Security and Access Control | Data security, reduction of fraud in the supply chain | [57] |

| Data security, traceability efficiency, reduction of query times | [58] | |

| Implementation of data encryption for privacy protection | [59] | |

| Quality assessment according to food safety standards | [60] | |

| Security, scalability, consensus efficiency | [61] | |

| Qualitative and Bibliometric Analysis | The article uses bibliometric metrics such as publication and citation count. | [62] |

| Cooccurrence analysis, number of publications, citations | [63] | |

| Word Frequency, Word Cloud | [64] | |

| Qualitative analysis with no specific quantitative metrics | [65] | |

| Ranking factors and AHP to rank Industry 4.0 tools | [66] |

| Technology | No. of Articles | Main Metrics Reported | Range of Results | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blockchain | 15 | Data security, latency, transaction costs | Fraud reduction 20–30%; latency < 2 s per transaction | IBM Food Trust, Hyperledger, OpenSC |

| AI/ML | 20 | Accuracy, recall, RMSE, R2 | Accuracy 85–95%; RMSE 0.12–0.35 | Crop prediction, classification models |

| IoT | 12 | Latency, packet loss, energy efficiency | Latency < 1 s; >95% successful data transmission | IoT sensors, ESP32, UAVs in traceability |

| Recommendation systems | 28 | Precision, recall, MAE, F1-score | Accuracy 80–92%; F1-score 0.78–0.89 | Crop, fertilizer, and e-commerce recommendations |

| Big Data/Cloud | 10 | Processing time, scalability | Large datasets processed in seconds; cost reduction 15% | Hadoop, MapReduce, NoSQL |

| Augmented reality/3D | 5 | Usability, operation times | 20% reduction in training time for operators | AR.js, Three.js, OpenCV |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arzuaga-Ochoa, M.E.; Acosta-Coll, M.; Barrios Barrios, M. The Validation–Deployment Gap in Agricultural Information Systems: A Systematic Technology Readiness Assessment. Informatics 2026, 13, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics13010014

Arzuaga-Ochoa ME, Acosta-Coll M, Barrios Barrios M. The Validation–Deployment Gap in Agricultural Information Systems: A Systematic Technology Readiness Assessment. Informatics. 2026; 13(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics13010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleArzuaga-Ochoa, Mary Elsy, Melisa Acosta-Coll, and Mauricio Barrios Barrios. 2026. "The Validation–Deployment Gap in Agricultural Information Systems: A Systematic Technology Readiness Assessment" Informatics 13, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics13010014

APA StyleArzuaga-Ochoa, M. E., Acosta-Coll, M., & Barrios Barrios, M. (2026). The Validation–Deployment Gap in Agricultural Information Systems: A Systematic Technology Readiness Assessment. Informatics, 13(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics13010014