1. Introduction

The main independent inter-governmental body at a global level is the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) created in 1989 with the purpose of protecting the international financial system by promoting and developing regulations to counteract crimes such as money laundering, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and terrorist financing. The recommendations of FATF are considered to be a standard for anti-money laundering (AML) and also for combating the financing of terrorism. The Forty Recommendations issued in 1990 by FATF were meant to combat the actions of drug dealers who used financial systems to launder money.

The current policies of European bodies prove permanent concerns in anticipating and also combating money laundering. The phenomenon as defined in EU Directive no. 849 of the European Parliament and Council, adopted on 20 May 2015, refers to the wrongful use of the financial system, and therefore preventing actions such as money laundering or terrorist financing, thus improving EU Regulation no. 648/2012 of the European Parliament and Council.

EU Directive no. 843 of the European Parliament and Council, adopted on 30 May 2018 (

European Parliament and Council 2018), stands as the most recent AML Directive, improving on EU Directives 2015/849 2009/138/EC and 2013/36/EU.

European directives underline the necessity of establishing Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) in all of the Member States, with the authority to request, analyze, and disseminate relatable data, which should also operate independently and autonomously with the sole purpose of relating criminal activities to suspicious transactions, thus preventing and most importantly combating ML and terrorist financing. FIU, as a central national unit, should receive relevant information linkable to ML, associated predicate offences, and terrorist financing in order to analyze and disseminate the results to competent authorities

At a FATF level, the law guidelines that deal with the functions of FIUs are soft and are not linked with EU law or the national laws of the member states. There are no harmonized specific rules regarding the legal status, organizational nature, function, investigative powers, and enforcement mechanisms. As a result, FIUs have the following four models: judicial, law enforcement, administrative, and hybrid models, each of them with their own particularities (

Pavlidis 2020).

The judicial model has full power and performs all of the functions related to receiving, analyzing, and if needed, seizing funds and freezing accounts. The second model implements AML measures aided by already existing law enforcement systems with a similar or better adapted jurisdictional authority to solve ML cases. Reporting entities deliver relevant data to the administrative model for processing and transmitting the results to the judicial and law enforcement institutions for prosecution.

The fourth identified model is a hybrid that uses mixed components of at least two of the FIU models (The Egmont Group).

No matter what the model of the FIU is, all of them have the role to receive disclosures from financial bodies and other institutions with such obligations. The necessity of reporting suspicious transactions by both financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs) to government FIUs represents a key element in the AML and CFT system functions (

Chaikin 2009).

In the context presented above, our paper highlights and covers the gap in the existing literature on suspicious transaction reports (STRs), and lays the foundation for future empirical studies based on them as a first formal sign of money laundering. It also shows opportunities for exploring the effectiveness of the AML regime and the steps that could be taken to achieve the objectives, rather than being a simple compliance tool.

The rest of the paper is presented as follows.

Section 2 presents the literature review in the field of money laundering, including the presentation of the concepts, mechanisms, countermeasures, and international and European legal framework.

Section 3 presents the methodology, which contains the working hypothesis, the evaluated sample, the period, and the method used, and the results obtained are presented in

Section 4, which contains the graphs, tables, and case studies. In the next section,

Section 5, the findings are analyzed and discussed, and for each working hypothesis, the conclusions are presented. The implications, restrictions, and recommendations, as a conclusion to our entire study, are presented in

Section 6.

2. Literature Review

The phenomenon of money laundering alongside terrorist financing represents a major problem within the EU, where there is an urgent need for effective measures to combat and counteract its effects. The repercussions specter is on the stability, integrity, reputation, and performance of the financial and economic sector (

Shaikh et al. 2021). The literature, research, and specialized studies on the economic and financial crimes are growing in number, but future efforts are needed in the field. Specifically, more effort needs to be made to fill the gaps through empirical analyses measuring the size of the informal sector, identifying the determinants and their mechanisms and correlation, as well as the effects on economic and financial crimes (

Elgin and Erturk 2018).

In the research undertaken, we did not identify a sufficient statistical analysis of suspicious transactions.

There are a number of articles that address the issue of suspicious money laundering transactions from a theoretical perspective (

Levi et al. 2018;

He 2010;

Simser 2013), as well as articles that address the same issue through case studies (

Naheem 2016;

Raza et al. 2020;

Gilmour 2020), but an approach from the statistical perspective of the suspicious transactions available in the annual reports for recent years has not been found.

This article approaches the theoretical part, as well as the statistical one, through case studies and statistical processing of suspicious transactions at an EU level. Thus, we aimed to cover this gap in the literature using research based on data that can be set out for a wider period of time and use in empirical studies.

The money laundering process has a long history, but has evolved and adapted to modern society, globalization, and digital transformation, causing major damage to citizens, companies, and states, becoming a catalyst for illegal activities (terrorism, fraud, and corruption) that lead to decreasing integrity and transparency, and creating a widespread lack of confidence in markets (

Dobrowolski and Sulkowski 2019). The money laundering operation involves the illegal act of hiding money from illicit activities and turning it into legitimate money (

Le-Khac et al. 2016;

Syed et al. 2019), thus changing the clandestine nature of money (

Qureshi 2017). ML is the transforming process through which dirty, illegal money appears to be white and clean (

Hetemi et al. 2018). According to the FATF, the money laundering phenomenon involves money laundering by adapting illegal profits in order to hide the true origin of fraud, bribery, prostitution, illicit sale of weapons, and others (FATF), and the IMF and UNODC specify that this process is carried out by an individual who dissimulates or conceals the illegal origin of income in order to create the impression that it is derived from legal sources (

IMF and UNODC 2005). Thus, a considerable part of the definitions have the same starting point and go in the direction of those issued by the FATF or UNODC: hiding the illicit origin and reintroducing it into the economy.

The money laundering mechanism, according to the literature, involves three stages (

Demetrias and Vassileva 2020, pp. 16–17): placement, layering, and integration. The first stage of money laundering is the most risky, because of the proximity of the true identity of income, with the possibility of being detected by the authorities (

Jayantilal et al. 2017) because it involves the introduction of illicit profits in the financial system (

The World Bank and Schoot 2003;

Jaara and Kadomi 2017). Stratification indicates laundering and disguising the illegal source through several transactions (

Demetrias and Vassileva 2020), and in the last stage, integration, funds or revenues are reintroduced into the legal economy (

Teichmann et al. 2020). Various methods of money laundering can be done nationally (“adding cash to the cash registry of a cash-intensive business”) (

Ferwerda et al. 2020, p. 3) or internationally (depositing dirty money by criminals in the bank), and targeting the financial system in order to lose the illegal mark with the help of offshore companies (

Ferwerda et al. 2020, p. 3).

At an international level, no specific, unitary definition of money laundering has been issued because each state defines this crime in its own way (

Van Fissen 2003;

Teichmann et al. 2020). As a result of the development and spread of this phenomenon internationally, decision makers have realized the magnitude and consequences of this phenomenon, as well as the importance of following the path of money and identifying measures to reduce and counteract the effects (

Christine 2013) on society, states, and fields of activity. This phenomenon has become a threat to the stability of financial systems, creating the premises for a consensus and a common struggle at an international level to develop efficient and coordinating levers in dealing with money laundering. The first step in this direction was initiated in 1988 at the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substance, Vienna Drug Convention (

Tiwari et al. 2020), through which a definition of the crime of money laundering was issued. Subsequently, in 1989, the Financial Task Force on Money Laundering was formed, which initially had responsibilities consisting of the analysis and development of methods to combat money laundering, and now is developing its mandate to include counter-terrorism actions and is issuing recommendations for combating these crimes (

Jayantilal et al. 2017).

Thus, the EU has provided a clear setting for the efforts against ML and terrorist financing, through the development of regulations and directives at a European level, according to standards adopted by the FATF, revised over time, mandating financial institutions and certain professions and enterprises to inform the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) about possible suspicious transactions (

Viritha et al. 2015).

European cooperation in this matter is carried out through specific structures, and also the EU platform for European FIUs, in order to achieve the transfer of important data leading to the rapid identification of facts and money laundering transactions, for analysis purposes and actions, in order to be as effective as possible at reducing possible threats and consequences (

Transparency 2015).

The European legislative framework, which refers to anti-money laundering efforts, has a main role in defending the financial system, as well as the professions prone to the risk of being used in inappropriate/illegal directions (

Transparency 2015). The European Union approaches the issue of ML from two intersecting perspectives, namely: criminalization and prevention (

Demetrias and Vassileva 2020, p. 13). Meanwhile, financial institutions have the obligation to comply with the provisions and to perform permanent monitoring of transactions in order to identify suspicious activities (

Alkhalili et al. 2021).

The attention paid by European bodies regarding the identification of procedures destined for anticipating and deterring money laundering was initiated in 1991, through the First Directive on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purpose of money laundering Council Directive 91/308/EEC. The main argument is derived from the ongoing concern that the financial and credit institutions can and will be used as a money laundering mechanism generated from illegal activities. The text issued in 1988 by the United Nations Convention against illicit drug trafficking is taken over by this directive for addressing ML offenses. ML prohibition, as well as identifying clients of financial and credit institutions by means of supporting evidence, must be ensured by the member states, with the exception of other credit or financial institutions that have the quality of client (

The Council of the European Communities 1991). This directive created the context of future regulations.

Directive 2001/97/EC of the Council and the European Parliament, from 4 December, required the update and completion of the provisions from the original directive, as proposed by the Financial Action Task Force and the involvement of specific professions in the anti-money laundering actions, alongside the financial sector. The Second Directive issued a broader definition of this illicit process, which includes “the conversion or transfer of property in order to hide its illicit nature; concealment or distortion of the nature, provenance, location, disposition, movement, and rights relating to the property or property right in connection with which the perpetrator knows that they come from a criminal activity; acquisition, possession, use of property, being aware at the time of receipt that it comes from a criminal activity” (

European Parliament and Council 2001, art. 1 C), and the introduction of other types of crime (corruption, fraud, and organized crime) by systematically incorporating tax offenses, called predicate offenses (

EUCRIM 2013).

The new regulatory framework include investment firms, exchange offices, real estate agencies, and casino activities (2001/97/EC art. 2a) because of the suspicion of possible transactions resulting from money laundering, as well as the “identification, tracing, freezing, seizure and confiscation of instruments and proceeds of crime” (

European Parliament and Council 2001, p. 53).

The 2005/60/EC Directive presented a special importance of FIUs for combating ML and terrorist financing, as demonstrated by the request included in the text advocating for a national central intelligence unit in all Member States (

European Parliament and Council 2005, art. 21), which receives and analyzes reports of suspicious transactions or other data on ML or terrorist financing, in order to transmit the results obtained to specialized agencies in the country (

Egmont Group 2021), was followed by the Commission 2006/70/EC Directive from 1 August 2006, setting measures for previous directive implementations. Although it is the third in AML action, it is the first to address the financing of terrorism, based on the policies mentioned in the other two texts (1991 and 2001), with new provisions and elements related to the realities of that period. The need for a new directive was reflected following FATF’s revision of the international ML standards and the inclusion of terrorist financing, amid the events in the United States on 9 September 2001, and the predilection of the European countries to implement the FATF recommendations only once (

Salas 2005, p. 2). The research undertaken by

Leite et al. (

2019) on the technology’s input in the fight against ML crimes shows that with the identification of suspicious transactions, the interest of researchers in this field has increased (

Leite et al. 2019). The intensification of money laundering actions within different fields of activity has generated increased involvement of authorities in regulating the extraction of unstructured data from suspicious activities based on statistical techniques (

Lokanan 2019).

Accelerated technological advances, both on the international and European stage, along with the equally rapid adjustment of criminals to them, have had, as an impact, the elaboration by the member countries of the fourth Directive (

European Parliament and Council 2015), with the purpose of updating and strengthening the provisions for preventing and combating money laundering (

Koster 2020), which is based on the regulations already adopted in the previous Directive. It also brings an element of novelty aimed at a risk-based approach, transparency and identification of vulnerabilities, and strengthening the existing norms at an EU level regarding AML and CTF, according to the directions approached by FATF. The normative act implies the observance by financial institutions and by vulnerable professions, such as auditors and lawyers, of the characteristic reporting requirements regarding the transactions performed by their clients, but omits the responsibility borne by them as well (

Rose 2019). At the same time, the orientation of this Directive is in the direction of protecting society from this increasingly common crime, as well as maintaining a stable European market (

Primorac et al. 2018).

EU Directive 2015/849 from 20 May 2015 repeals Directive No. 3 (

European Parliament and Council 2006), Directive 2005/60/EC, and amends no. 648/2012 EU, introducing new regulations (

Deloitte 2017;

European Parliament and Council 2015), as follows: introduction of new terms and their definition, establishing a database or central register, collection of information on the real beneficiaries, promoting effective cooperation, applying more rigorous administrative sanctions, and maintaining and improving important and complete statistics in order to transmit them to the Commission.

The fifth Directive—EU Directive 2018/843 on combating money laundering—took effect on June 2018 (

European Parliament and Council 2018), and amends the previous Directive (2015/849) and establishes new provisions to effectively combat the process of terrorist financing and to consolidate a high transparency in financial transactions, as well as the definition for the concept of virtual currency, and the introduction of measures to regulate them in European Union law (

Haffke et al. 2020). According to the European Central Bank, there are three types of virtual currencies: the first type presents the currencies introduced in a closed circuit; the following virtual currencies are unidirectional ones, which can be used to make payments or buy goods/services, and the third type are the two-dimensional ones called cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin) (

Vandezande 2017, p. 341).

The magnitude of the development of the cryptocurrency segment and the possibility of its abusive use by becoming a preferred platform for illegal activities (

Șcheau and Zaharie 2017) in order to launder money has led to the expansion of international standards on the virtual assets market (

Covolo 2020).

EU Directive 2018/843 (

European Parliament and Council 2018) focuses on (

European Commission 2018) optimizing transparency over ownership of companies and trusts, rigorous controls for high-risk countries, highlighting the risks regarding prepaid cards and virtual currencies, extending the provisions to art dealers and tax services, and national financial intelligence units to strengthen the cooperation and the competencies of FIUs and to improve collaboration and data exchange from the European Central Bank to the supervisory authorities.

The AML and terrorist financing war are in full swing, as highlighted by the efforts of the authorities resulting from the issuance of regulations and provisions embodied in the five Directives, periodically updated according to the risks and threats that can occur at a European level as well as worldwide. An effective step to be taken is represented by the development of the FIU network and the global collection and analysis system (

Gelemerova 2008), as well as the strengthening of cooperation, because a lack or poor evaluation is the main obstacle of the system to combat and deter money laundering (

Ponomarenko et al. 2018).

As can be seen, there is poor literature regarding the items that constituted one of the first triggers of money laundering investigation, suspicious transaction reports (STR). Our research and analyses fill a gap in the literature regarding these items by presenting the trends and effectiveness of money laundering countermeasures from the perspective of a number of suspicious transactions reported to the Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs), number of analyses submitted to law enforcement authorities, and typologies of cases in European Union Member States. In Europe, a series of measures was designed to expand the area of the entities obliged to submit reports with suspicious activities, so that a competent body with new legal rights and powers can start their analysis and send the results to law enforcement authorities. Starting from these, we intend to verify if there is a link between the legal provisions and items related to anti money laundering in terms of the effectiveness of the countermeasures to these items, by stating the following working hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1. European money laundering countermeasures are efficient in terms of a larger number of suspicious transactions brought to light.

Hypothesis 2. The last European decisions are in trend with new money laundering techniques.

Hypothesis 3. There is an increase in cases sent for further investigation and prosecution.

3. Methodology

In order to test our hypotheses, we used descriptive statistics to process data and case study methods from annual reports of the European FIUs for 2018 and 2019.

As mentioned above, every country that applied FATF standards and AML compliance, for this scope, must organize its own FIUs as a national body with attributes to receive different types of reports and information, so as to analyze and disseminate the results obtained to other authorities for further investigation and prosecution.

The data analyzed are available in the national FIUs annual reports for 2018 and 2019, as elaborated and published by the European Union Member States under the provision of article 44 (3) from EU Directive 2015/849, which stipulates: “Member States shall ensure that a consolidated review of their statistics is published”. These reports contain mainly data such as the sectors with a high risks of money laundering; the volume and number of cash transactions; external transaction and suspicious transaction reports (STR); the number of reports or files investigated; the types of predicate offences; the value of the property in euro that has been frozen, seized, or confiscated; the number of requests for information sent or received between FIUs; and the case studies from the last period.

The analyzed samle was selected because FIUs of European Union countries operate in a common space and are subject to the same regulations and legal norms, therefore the data reported annually are comparable in structure and are public.

The time frame selected for analysis coincides with the final term for the implementation of the latest European AML Directive, the directive issued in June 2018, with a deadline for transposition into national legislation of January 2020; therefore, the statistics available in the field for 2018 and 2019 more or less reflect the result of the new European measures.

Thus, reports from the 20 FIUs of the sample were identified for 2018 and 2019, and the data were extracted, organized in a database, and processed through descriptive statistical analyses.

The data extracted for the present study, from the reports prepared by FIUs, include the number of suspicious transactions reported to the Financial Intelligence Units in the EU Member States, the number of cases submitted for investigation to the competent authorities, and case studies on the latest cases investigated. Based on the analysis of the extracted data and the information provided through the case studies, as well as other elements and statistics from the analyzed reports, it was possible to issue opinions on the effectiveness of measures to prevent and combat money laundering at a European level.

4. Results

4.1. Suspicious Transaction Reported and Other Information Relevant to Money Laundering

In their role as national coordinators of the activity for preventing and combating money laundering, Financial Intelligence Units receive from obliged entities, but also from other entities, reports of suspicious transactions, reports of suspicious activities, reports of unusual transactions, and statements of suspicion in order to ensure a homogeneity of the analysis found in the previous statistical data under the name of a suspicious transaction report, as is defined in EU Directive 849/2015.

Starting from the premise of transposing European directives, the evolution of the number of suspicious transaction reports (STRs) or suspicious activity reports (SARs) received by FIUs in 2018 and 2019 were analyzed according to the data presented in the national reports prepared by these bodies.

Researchers have found there are no clear rules, criteria, or standards about what constitutes and what does not constitute suspicious activities or transactions. In most situations, the pressing concern of the financial institution is on a reporting suspicious transaction report (STR) adequately to avoid punishment from the authority—FIU (

Yasaka 2017, p. 3).

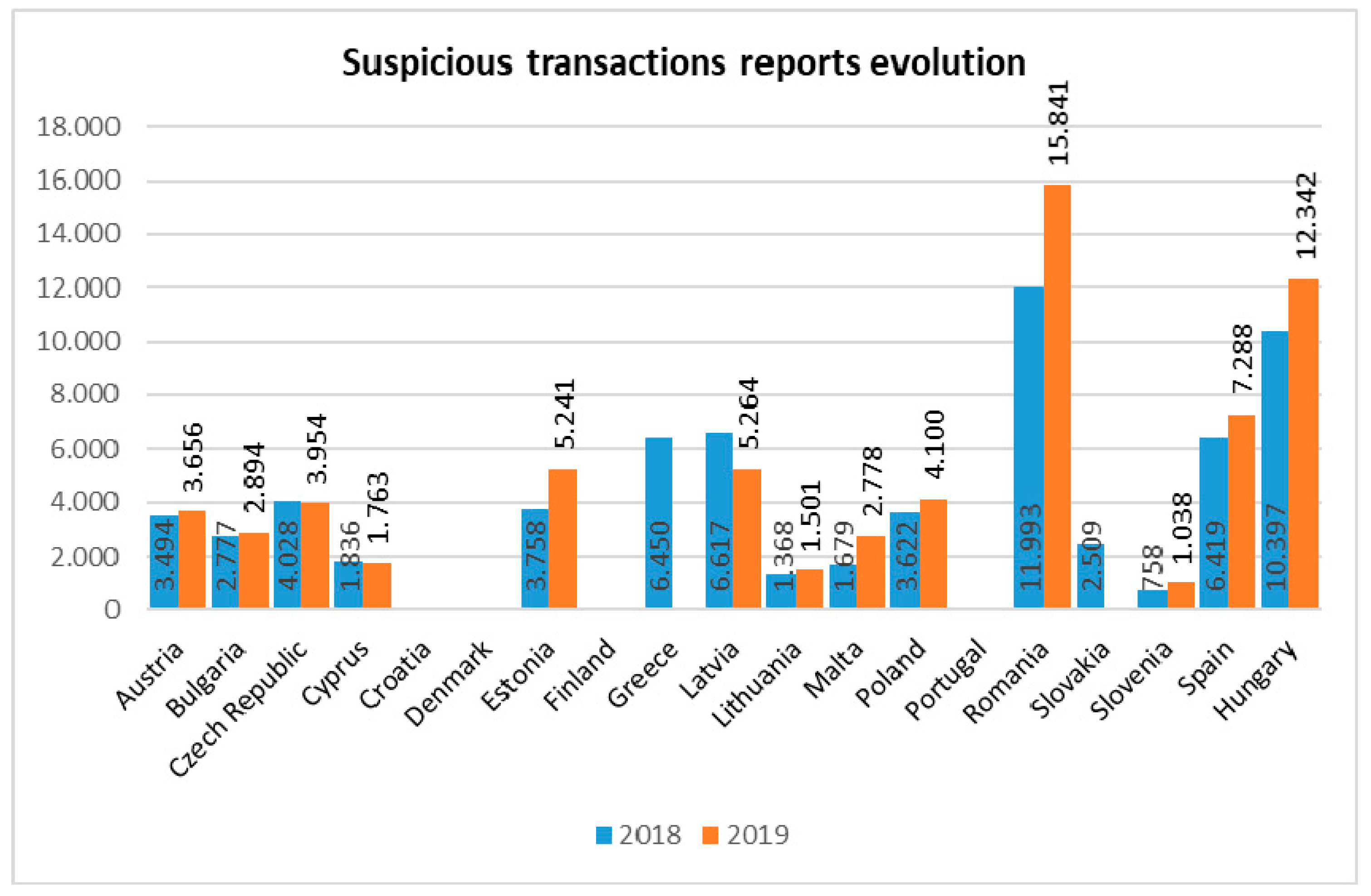

Of the 27 Member States, for seven, no reports or data on suspicious transactions were found, and of these, for four countries, no reports were found for 2018 or 2019, and for three countries, no reports or data on STR were found for 2019. As can be seen from the results from the graph below,

Figure 1, for 10 states out of the 19 included in the analyzed situation, there was an increase in the number of suspicious transactions received by FIUs, with an increase of between 4.21% for Bulgaria and 65.46% for Malta, and for three states the number of reports of suspicious transactions decreased.

Eight Member States not included in the chart above were analyzed separately, motivated by the large number of STR received—over 20,000—compared with the other states, according to

Table 1. Of these, five states registered an increase in the number of STRs, two registered a decrease, and in the case of one state, the data for 2019 were not known.

Of these, three countries were analyzed, two with the highest increase (the Netherlands and Germany) and one with the highest decrease (Belgium), in order to identify the reasons for these developments. Germany had an estimated 49% increase in 2019 compared with 2018, which only underscores the importance of the FIU’s role in analyzing, filtering, and disseminating only those results that contain specific indicators of suspicion. The need for a unitary understanding of the associated risk from all actors involved in preventing and combating money laundering is also considered, without specifying the factors that led to the increase. It is mentioned that in 2019, some credit institutions submitted separate STRs on the subject of the “laundromat” to the German FIU for the first time. These reports contained a very large number of transactions, mainly consisting of correspondent banking activities.

The regulatory framework in this area mentioned in the Belgium report is a national law released in 2017, before the 843/2018 EU Directive, thus the differences between the number of STR from 2018 and 2019 were not due to European legislative changes. Pursuant to the 2019 report of the Belgian CTIF-CFI, 25,991 reports were received from complying institutions, which constituted a considerable decrease of 22% compared with 2018. The competent body estimated that this decline in the number of disclosures was largely due to changes in the way they were reported to CTIF-CFI.

A particular case is the Netherlands, where the number of unusual transactions rose highly from 753,352 in 2018 to as many as 2,462,973 reports in 2019. This increase was generated by the inclusion of a new suspicion reporting criterion, an indicator for high-risk countries. Thus, out of the total number of unusual transactions, 1,921,737 were reported to FIU-Netherlands in 2019 based on this indicator. All of these transactions were analyzed, resulting in only 686 suspicious transactions. In order to ensure a higher correlation between the inflows (unusual transactions reported) and outflows (suspicious transactions following the analyzes performed) in 2019, the aforementioned indicator was changed. The anticipated effect was a reduction in the number of unusual transaction reports in 2020, a reduction caused by this adjusted indicator. Because of the particular situation in these analyses, the so called “regular” unusual transactions mentioned were used, which were 541,236, a significant increase from the 394,743 reports in 2018.

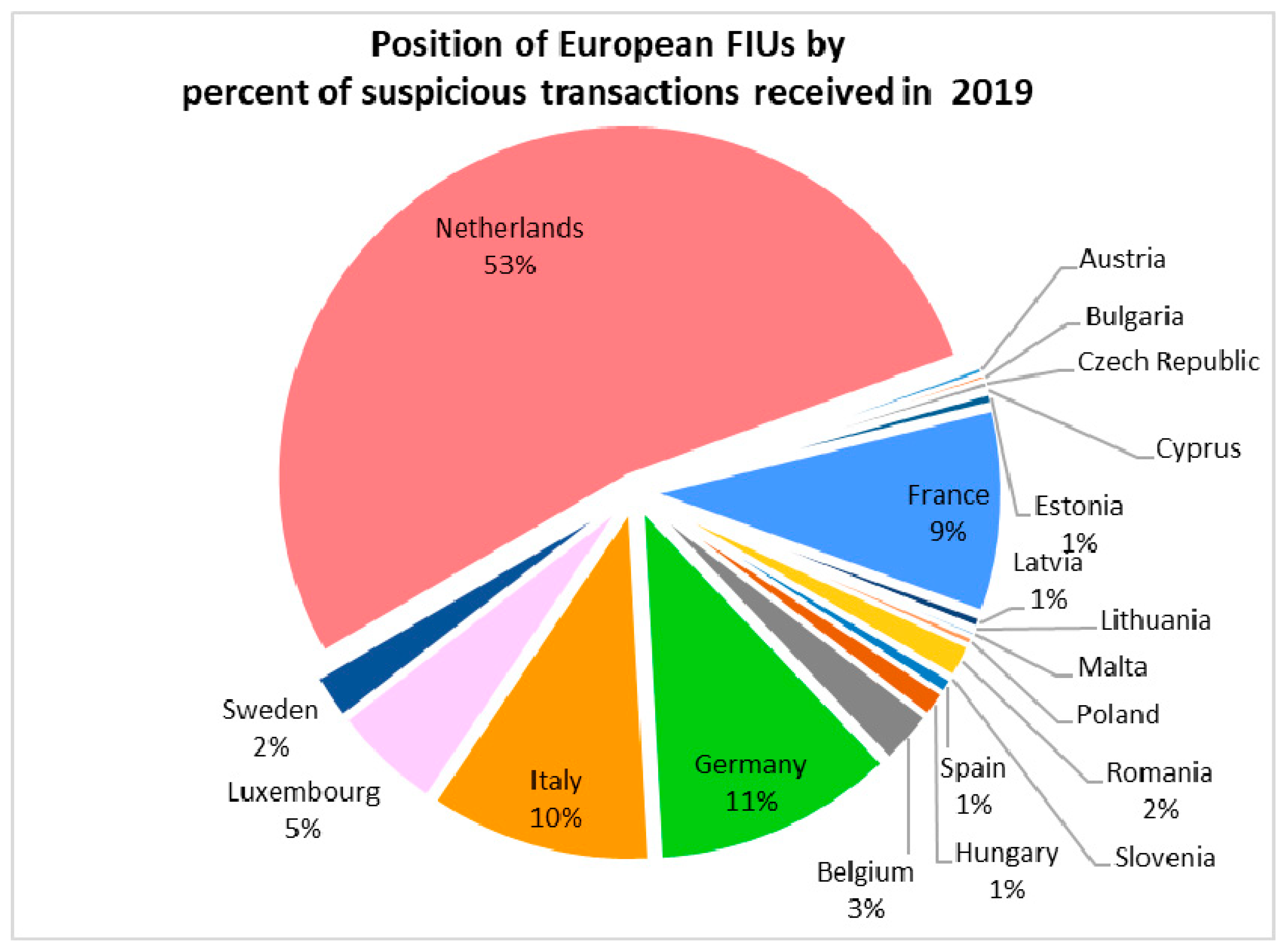

In the European Union, the situation of nations viewed through the prism of the number of STR received in 2019 from the reporting entities is presented according to

Figure 2.

The typology regarding the determination of the number of suspicious transactions declared by the Member States is variable and different from one country to another (

Cotoc et al. 2020), and these differences between the reporting of the statistical data found in 2018 were also maintained in 2019. Thus, annual reports contained only new transactions in the reporting year or both new and old transactions (Bulgaria), suspicious transactions regarding all types of crime or specifically only the number of money laundering and terrorism financing transactions, suspicion-based reports also include inquiries (Estonia), suspicious transactions or suspicious activity (Luxembourg), national and foreign received reports from suspicious transaction like Belgium and Lithuania, or only SRTs from national obliged entities (Cyprus).

4.2. Case Studies Resulting from Suspicious Transaction Analysis

4.2.1. Description of Money Laundering Cases

All information; requests for information; reports about suspicious transactions, activities, or unusual transactions; statements of suspicion, as well as threshold reports or other types of data and information received by the FIUs were analyzed according to the technical and human capacity of each national body. The analyses performed resulted in information on the most representative money laundering typologies and techniques in terms of frequency, volume of transactions, or economic and social impact for the activity of 2019.

Offences in the case studies from 2019 reports were consequences of economic and financial crime determinant factors, as presented by

Achim and Borlea (

2020), such as economic growth, tax pressure, financial and banking system evolution, technology, digital economy, public governance considered through the efficiency of institutions, the quality of regulations, the rule of law, etc.

In the European Union, the most important crime in terms of the trends and typology in the money laundering phenomenon is fraud, in its various forms, namely: carousel fraud presented in Germany and Belgium, social benefits fraud and investment fraud in Austria, online fraud in Cyprus and Sweden, social engineering fraud and virtual currency fraud in Lithuania, and social fraud or fiscal fraud in Belgium, with this also being mentioned for Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, and Latvia. It is followed as an incidence of tax crime, corruption and bribery, drug and human trafficking, organized criminal group, casinos and gambling, real estate investment, the increasing use of payment services, professional money laundering, and the virtual currencies trade.

In the prepared reports, with a few exceptions (Ireland, Romania, and Spain), data were presented, as well as sometimes rankings on the main crimes resulting from the analysis of suspicious transactions and activities, but also case studies from 2019 for various types of money laundering. For example, Belgium presented six case studies on the structure trends identified, cases, action taken, and awareness-raising. France presented 14 case studies, of which 7 were from the reports of obliged entities and 6 were from the TRACFIN analysis of the France Financial Intelligence Unit, as well as 1 case with international cooperation. The German FIU presented 11 case studies, the Czech Republic presented no less than 16 case studies, and the examples can continue. From all of these cases results, the complexity and diversity of money laundering actions, but especially the extremely important role of national bodies in identifying, analyzing, and stopping these activities, was considered.

In all of the cases presented, money laundering techniques in at least one of the money laundering stages can be identified (

Figure 3).

The study by Unger, 2017, amply dealt with the techniques and methods used in the money laundering process: the use of the financial system (either the formal ones, like banks or money transfer offices, or the informal ones such as “hawala”), the physical movement of cash, such as that carried out by cash couriers or shipping containers, which may be described in general terms as “trade-based money laundering”, disguising the origin of criminal money by hiding it in legal exports and imports of goods and services (

Unger 2017).

As for laundering techniques, the well-known and most used are smurfing and structuring, currency smuggling, travelers’ cheques, gambling, casinos, fictitious sales and purchases, shell companies, capital market investments, real state acquisition, trade based money laundering, on-line banking, and virtual currencies.

4.2.2. Examples of Cases

Professionals Working for Criminals

One of the Belgian case studies is about money laundering using shell companies through accounting and legal professionals.

These shell companies were used as facades, involved in areas that Belgians consider high-risk sectors from a money laundering perspective, such as construction activities, cleaning activities, import and export, or the hospitality sector. Postbox addresses were most often run by young managers of a foreign origin or nationality. Some of them were contacted as soon as they arrived in Belgium, even though they did not have the necessary skills to manage a company.

The case study showed that the lawyers or accountants gave assistance or took over the task of setting up companies with payment for the start-up costs, elaboration of a business plan, registration in the necessary national records, preparation of reports and financial statements, and the provision headquarters and logistics. All of these elements show that the professionals implicated make their knowledge available to various criminal networks. The files set up in these cases were forwarded to the Belgian authorities.

Similar to the previously mentioned case, the Czech FAU brought attention to a case considered much more serious than the others, determined by the fact that professional money laundering was provided by legal professionals (lawyers) who were part of an organized group. For a long time, they “successfully” and repeatedly used the same money laundering scheme, applied internationally, offering, in addition to classic services of setting up a company, opening bank accounts, including issuing false documents to justify the transfer funds. The common typology of the incorporated entities was that they were “shell” companies with fictitious addresses and that did not actually perform economic activities.

Funds in the order of millions of euros were laundered/legalized in the period of more than a year. Czech FAU confiscated CZK 8 million and reported a suspicion of committing the offense to the Legalization of Crime Proceedings.

Business e-Mail Compromise (BEC) Fraud

The Swedish report mentions fraud in various types as the most frequently reported crime: from merchandise that was never delivered after payment, with initial contacts made through ads in online marketplaces or through social media (where romance scams are also becoming increasingly common), to more advanced schemes such as BEC fraud and vishing (

Polisen Swedish Police 2019).

The purpose of BEC fraud is to become the recipient of erroneous payments. The most common method is that by which a fraudster pretending to be a senior executive of a company sends an e-mail to the company’s financial director requesting payment to an account from abroad. This is made possible through an earlier data security breach or through manipulating the sender’s e-mail address (spoofing). The common factor of this type of action is that the money is transferred to another country so as to make recovery difficult and to then launder it. It is possible that the bank where the money is transferred to detects the fraudulent transaction, because there are often inconsistencies in the name of the recipient of the transfer and the name of the holder of the bank account.

Use of New Payment Methods

One such case was presented in the Belgium FIU report. (

Belgian Financial Intelligence Processing Unit 2019) Criminals were currently using modern alternatives for trading and payment cryptocurrencies, payments through payment service providers’ accounts, and virtual currency trading platforms.

The Belgian financial intelligence unit identified several cases in which vouchers were used as tools to facilitate money laundering by removing the links between victims and offenders.

The victims were persuaded to buy vouchers from petrol stations or shops where terminals were available for printing tickets for online vouchers. These vouchers with fixed values in euros contain a printed 16-character code valid for online shopping. After the purchase of the vouchers, the victims communicated the code written on the voucher to the offender, who used it for payments on a gaming site, which ensured the supply of bank accounts. Banks had no suspicions, as the money came from online betting. Thus, in the banking system, there was no connection between the origin of the money and the victims of fraud. Merchants who own ticket distribution terminals are not subject to the law on the prevention of money laundering and voucher providers have no record of individual payments made for the purchase of vouchers.

This sophisticated circuit based largely on the online environment ensured both obtaining money of an illegal origin (committing fraud) and laundering these funds by integrating money into the financial circuit, without being able to establish a link between source–victim–offender.

Cyber Fraud

The Estonian FIU identified a recent cyber fraud scheme (

Estonian Financial Intelligence Unit 2020). The people accused of fraud claimed to own a company whose object of activity was directed towards investments such as precious metals, solar energy, etc. (titanium plates were offered, which are supposed to have a very high market value and thus contribute to the enrichment of the beneficiaries), therefore the company had a bank account at Mack Gold and was a major customer of the bank. The fraudsters claimed that the bank wanted to give them a gift as their main customer: the company could buy luxury cars by paying only 40% of their price, the remaining 60% would be paid by the bank on behalf of their customer. The corporation itself did not need these cars, and so, in turn, offered them to people who might have been interested. The only condition was that the people took the cars to their country and paid 40% of the invoiced amount to a bank account abroad (United Arab Emirates). The bank would then pay 60% of the price to the car dealer, after which the person could pick up the car at a showroom. Another condition was that the person needed to pay a membership fee of 200 euros in order to become a member of the company, because the offer was applicable only to people in the company. It is a common feature of cyber fraud that, in order to receive an offer, service, or gift, a person must contribute to some extent. The first payment is usually not large, it is not considered much compared with the expected benefit. However, in most cases, the victims did not receive anything, only new requests. If the value of the goods and/or services to be purchased does not correspond to the deposit, in most cases, you will be dealing with fraud. Therefore, especially in the case of online transactions, it is necessary to maintain common sense and to think twice about whether the offer is in line with reality.

In cases of cyber fraud, it is possible not only to fall victim to it but also to become an accessory to it. This happens when a person allows funds of unknown origin (possibly dirty money) to be transferred to their account. A small fee is charged, the rest are withdrawn or transferred to a third party. Such a person is known as a money mule and may also be liable as an accessory to a criminal offense.

Illegal Virtual Money Changer

The Netherlands FIU described in its report a case of unlawful exchange of virtual currencies. (

FIU-The Netherlands 2019). The report made a detailed analysis of person who carried out the suspicious transactions, which were determined as a result of large withdrawals of amounts from current cash and deposits, the request to change small euro banknotes into high value banknotes, as well as gambling wins.

The suspect exchanged Bitcoin for money, outside the regulated framework, without asking for details about the origin of Bitcoin or the identity of its customers. The meetings for the exchange took place in public places, with all of the transactions thus being carried out in complete anonymity. It is a well-known practice of criminals to pay the cost of anonymity through higher fees for exchanging virtual currencies than the fees charged in the foreign exchange offices. During a search in one of the suspect’s locations, an amount of 11,000 euros in cash and 27,000 euros or equivalent in Bitcoins in a digital wallet were also seized. The suspect was eventually arrested for money laundering by criminals from illegal activities, and it was established that he exchanged the Bitcoin for 600,000 euros that year.

4.3. Tthe Results of FIUs Analyses Dissemination

After analyzing cases opened by FIUs based on information transmitted by obliged entities, other authorities, or the spontaneous dissemination of information, those cases that contain clear indications regarding money laundering or other kind of offenses are sent to enforcement authorities or other authorities.

Depending on the legal system in European Union countries, judicial authorities are the police, prosecutor’s office, intelligence services, Central Anticorruption Bureau, and other enforcement institutions.

Given this diversity of organizations of the judiciary in European countries, this study considers the dissemination of information to the competent authorities as a whole, whether it concerned judicial authorities, tax authorities, customs, intelligence services, or other authorities.

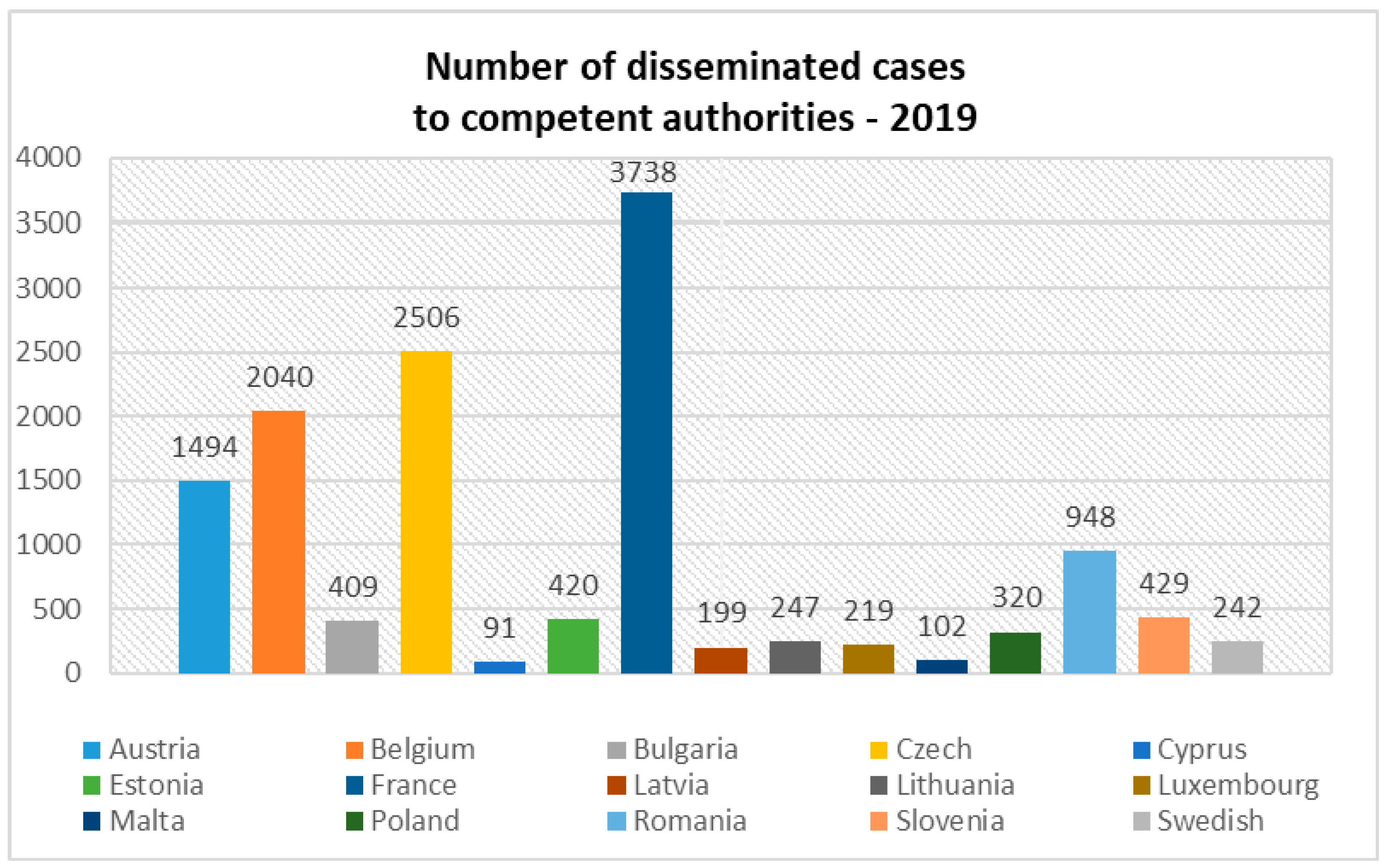

During 2019, the number of money laundering information sent to the authorities registered a very large variation: between 91 in Cyprus and 3738 in France, as shown in

Figure 4, comprising 15 states that communicated these data in the annual reports, and between 7646 files disseminated in Italy and 41,369 in Germany according to

Table 2, which includes those FIUs from countries with more than 7000 disseminated reports.

The German FIU disseminates STRs where, in the analysis process, sufficient indications of money laundering are identified to the competent State Office of Criminal Investigation (LKA). In 2019, more than a third of the analyzed cases were sent to the authorities, while in 2018, more than half of the STR were disseminated. The FIU performed its filter function even more efficiently under the strain of the constantly increasing total number of STRs from the state’s national body.

In 2019, 39,544 transactions were identified as being suspicious by FIU the Netherlands, a decrease compared with 2018 when 57,950 transactions were considered as suspicious. Thus, 2018 remained the year in which the highest number of suspicious transactions were declared since FIU-the Netherlands was formed. Although the number of case files significant decreased from 8514 in 2018 to 5302 in 2019, the value of these transactions in 2019 was more than 19 billion euro, double compared with the value in 2018.

In Spain, the number of analyzed cases concluded in 2019 was related not only to those opened in 2019, but there were also cases closed that were opened in 2018.

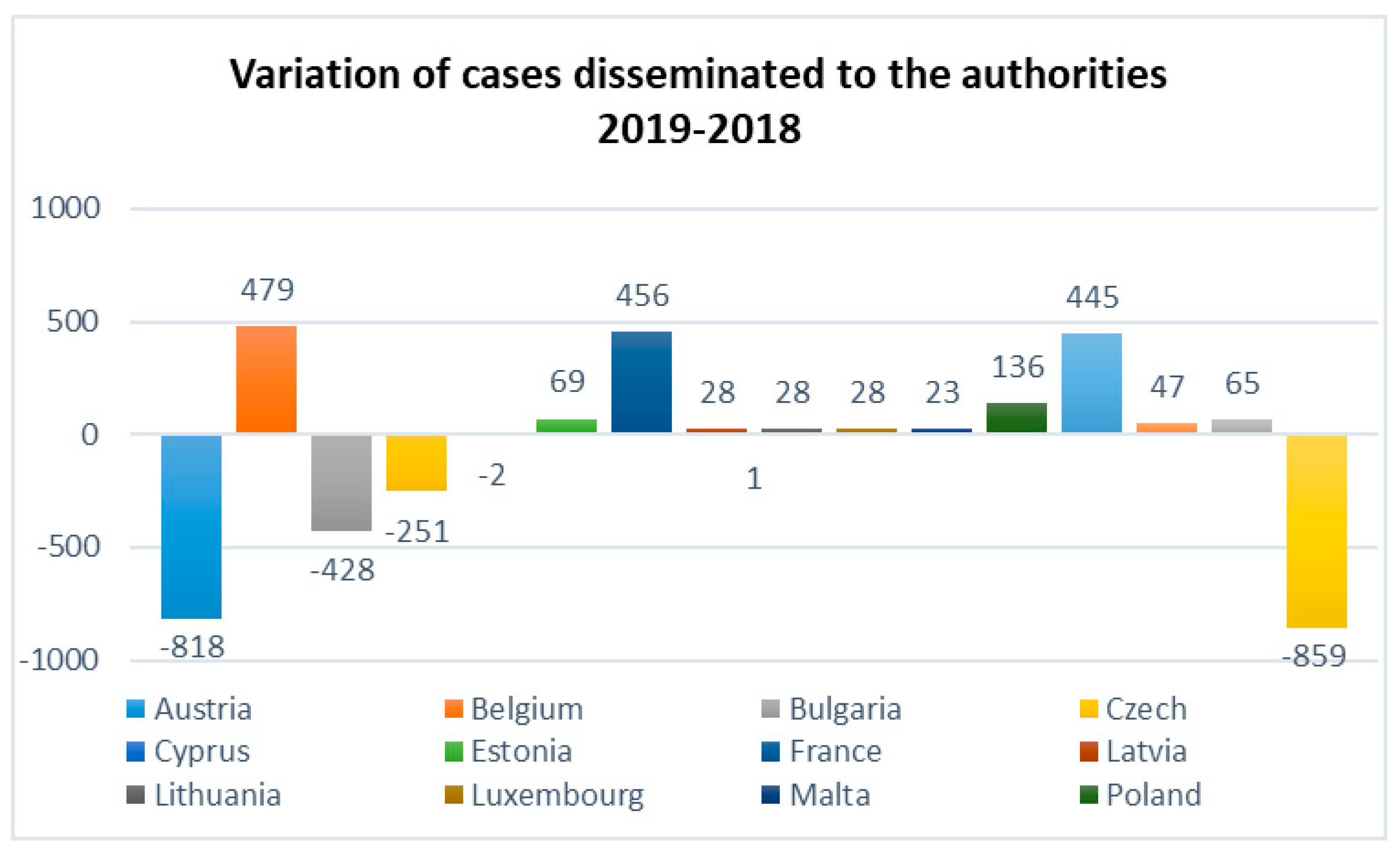

As a trend, compared with 2018, in 2019, for 10 cases there was a growth in the number of files submitted to the authorities, in 9 situations there was a decrease, and for 8 FIUs the necessary data were not identified.

Following the data processing, in

Figure 5, the difference between 2019 and 2018 is graphically represented as the number of cases transmitted for 16 countries and for 3 other countries, where Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain were not included in the processing because of differences of more than 1000 cases between the two years.

5. Discussions

5.1. Discussion Regarding STR

The measure of introducing new reporting entities through European Directive entities operating in areas of activity that are susceptible to money laundering risk has contributed to increasing the number of STRs reported to FIUs. Obliged entities according to the provisions in the 849/2015 EU Directive are: credit and financial institutions, auditors, accountants, tax advisors, notaries and other independent legal professionals, trust or company service providers, estate agents, other persons trading in goods in cash at an amount of EUR 10,000 or more, and gambling service providers. The list of obliged entities was modified for some entities and was completed for the 843/2018 EU Directive, with providers engaged in an exchange of services between virtual currencies and fiat currencies, custodian wallet providers, persons trading or acting as intermediaries in the trade of works of art and persons storing, and trading or acting as intermediaries in the trade of works of art when carried out by free ports.

Redefining the term of a real beneficiary and making the owners of companies transparent through the obligation to create the ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) register with wide access also determined the additional identification of suspicious transactions consisting of the transfer of funds between companies located in different states that have the same final beneficiary, namely transfers that are unjustified by economic activity.

The methodology developed by the EU for the identification of high-risk third countries have, in some cases, led to an artificial growth in the number of reported unusual transactions.

Other measures taken in the European Union that have led to a rise of suspicious transactions being reported are defining the concept of virtual currencies and regulating their market, intensifying collaboration between Member States both in terms of the number of interactions and the speed of communication through a common electronic platform, strengthening supervision at a European level by giving increased powers to the European Central Bank (ECB), and tightening the sanctions applied in cases of defiance of the relevant regulations in the field.

All of the above-mentioned measures have contributed to increasing the number of STRs reported to FIUs, which confirm that European money laundering countermeasures are efficient in terms of a larger number of suspicious transactions being brought to light.

Impediments to a robust analysis are that not all countries from the EU have transposed the AML directives within the stipulated deadlines, with differences of even two years between the time of transposition, which prevents a comparison of data on an equal footing; language barriers, where some states have published reports only in the official language of the state, not in English (Austria, Luxembourg, Hungary, etc.); the method of the statistical aggregation of data on suspicious transactions and their communication through FIUs reports are unregulated; and not all states from the European Union have complied with the EU Directive provisions of the Annual Report.

In order to ensure a real comparability between states from the perspective of the number of STRs, it is necessary that the data provided have the same calculation and communication methodology. From this perspective, the results highlighted in the graphs presented must be viewed with caution, with the data allowing us to decide with certainty about the trend and effectiveness of money laundering countermeasures at an individual level for each Member State, but not at the level of aggregate data.

5.2. Discussion about Case Studies

The case studies or examples presented are treated together as current trends and typologies in the context of money laundering, as the analyzed reports do not draw a clear boundary between predicate offenses as a source of illicit funds, and their methods and techniques of money laundering caused by the legislation of Member States for how economic crimes are defined and sanctioned, including money laundering.

A first conclusion of the case studies presented is that criminals are constantly looking for alternative channels through which to use the funds. They use the latest facilities of banking transactions for money laundering. These include the emergence of new players in the financial field, new bodies offering diversified payment services, increasing the speed of use and the ease with which funds are transferred to the traditional financial system, and new payment systems. An increasing trend in the use of professional services (accountants, auditors, and lawyers) in money laundering activities is noticed. Among the measures that can be taken to counter money laundering are risk assessment associated with new financial institutions, professionals and their supervision by FIUs that have responsibilities in this regard, the creation/use at the level of obliged entities or monitoring software based on the risk assessment of transactions, and the generation and transmission of persons/services with responsibilities in the field of real-time alerts.

The effect of globalization on new money laundering methods is noticeable: in the vast majority of case studies presented, there are transfers to accounts abroad, regardless of whether they are accounts at banking financial institutions or accounts/wallets on cryptocurrency trading platforms. Given the resolution during 2019 of some cases involving virtual currencies, it can be concluded that the measure of their regulation by EU Directive 843/2018 has produced positive effects, but it is necessary to closely monitor this area and to constantly update the relevant legislation, because cryptocurrencies, their trading mechanism in the profile markets, and their influence in the financial space are not sufficiently classified and systematized either as studies and theories or in practice (

Szetela et al. 2021).

All of these practical cases investigated confirm the hypothesis that the last European decisions are in trend with new money laundering techniques.

The current challenge for financial institutions is to ensure a balance between offering new money transfer functionalities to customers, while making them transparent and secure in order to allow for anti-money laundering at the same time. Among the ways to achieve these goals are informing the customers on the potential risks and the continuous training of all staff involved in the fight against money laundering with the presentation of the latest methods used by criminals, indications of suspicion, and tools they have in their provision for prevention and control.

5.3. Discussion about Information and Cases Disseminated to Competent Authorities

As shown above, the number of suspicious transactions and their evolution can be considered to be an indicator of the effectiveness of money laundering countermeasures at a national level, and could be an indicator of efficiency at a European level, given that it creates unitary methodological rules as a way of reporting—rules that can be developed without affecting the specifics of each Member State.

Case studies are also a good tool for reflecting both the effectiveness of measures covered by European directives and the trends in crime, which lead to new measures to counter them.

The same cannot be said about the number of information or files disseminated to authorities, which leads us to the conclusion that our third study hypothesis is not validated.

From the processing of data collected from the annual reports of FIUs, no conclusions can be drawn on the efficiency or effectiveness of AML, not even at a national level, with the data being inhomogeneous. Thus, countries were identified in which there was a growth of suspicious transactions, but a decrease of files disseminated to the authorities (Austria, Bulgaria, and Germany); countries in which both the number of STRs and the number of disseminations increased, but in different proportions, with the rate of increase in dissemination being lower than the growth rate of suspicious transaction reported (Estonia, France, and Malta); and countries where the number of suspicious transactions reported decreased, but the number of disseminations increased (Belgium and Lithuania).

6. Conclusions

This paper emphasizes that international money laundering regulations have a major impact and important results on fighting against money laundering. This research based on data collect and analyzed from 20 reports of European Union Member States’ FIUs highlights an increase in suspicious transactions reports (STRs) received by anti-money laundering national bodies between 2018–2019, and the newest money laundering scheme of the national Financial Intelligence Units as an effect of European Union measures and the transposition of this in national laws.

The main changes contained in the European directives on suspicious transactions are largely reflected in the statistical data of FIUs annual reports through the increasing trend in the number of suspicious transactions, where 75% of the Member States have available data.

The comparative study of the annual reports for 2018 and 2019 shows that steps have been taken at a European level in terms of the quantity and quality of STR. The quantity of suspicious transaction reports can be used as an indicator of the effectiveness of AML in each state, but not at the entire European Union, motivated by the aforementioned limits.

In a more specific sense, in order to fight against the concealment of illegitimate money effectively, it is first necessary to know the trends of the phenomenon at a European or global level, and for this, a synthesis of recent case studies is more than useful. In fact, these case studies are successful models and examples of good practice. Their dissemination is beneficial to all Member States and their government bodies for adopting the best action and legislation for AML.

Starting from the collected data, the hypothesis of measuring the efficiency of the number of cases disseminated to competent authorities was refuted as not being able to issue a general conclusion, globalized at an EU level, on the efficiency of money laundering countermeasures in terms of this indicator.

The results of this study support governmental and non-governmental entities by highlighting the areas that need immediate attention in order to downsize the effects of ML. It is not enough to set global rules or to have countries implement them and show that they meet the standards. They must also produce effects. In order to strengthen the effectiveness of AML and CFT, the implementation of relevant EU legislation in line with international standards in the fight against money laundering and how it is implemented must be regularly evaluated.

We appreciate that, in the context of technology development, there can be ways to ensure a transparent and standardized statistical report in order to ensure that the phenomenon can be researched on the basis of robust databases.

All of the indicators analyzed should be considered in future research for the possibility to appreciate the efficiency of anti-money laundering efforts. For this, a standardized methodology for reporting statistical data and case studies is certainly needed.