Abstract

Motivated by new financial markets where there is no canonical choice of a risk-neutral measure, we compared two different methods for pricing options: calibration with an entropic penalty term and valuation by the Esscher measure. The main aim of this paper is to contrast the outcomes of those two methods with real-traded call option prices in a liquid market like NASDAQ stock exchange, using data referring to the period 2019–2020. Although the Esscher measure method slightly underperforms the calibration method in terms of absolute values of the percentage difference between real and model prices, it could be the only feasible choice if there are not many liquidly traded derivatives in the market.

1. Introduction

Empirical studies show that real financial markets are incomplete, which means that not all derivative securities like options are replicable by means of some initial capital plus the value process of some self-finance trading strategy, and therefore hold unhedgeable and undiversifiable risks. The second fundamental theorem of asset pricing implies that in incomplete markets there typically exist several martingale measures consistent with the no-arbitrage principle that can be chosen as pricing measures (see, e.g., Jeanblanc et al. 2009; Shreve 2004). In fact, the range of option prices composes the total range between the inf and the sup of expected values with respect to martingale measures, and is therefore too large for practical purposes, see (Eberlein and Hammerstein 2004, Theorem 11.55).

Therefore, it makes sense to select a particular martingale measure for pricing purposes. In this study, we introduce, discuss, and compare two methods for the simulation of European call option prices: one based on the Esscher martingale measure and the other on the calibration to real-traded securities with an entropic penalty term. We implemented them in the programming language R and contrast the simulated derivative prices with real data retrieved from NASDAQ option chains. The objective of the paper was to provide a good fit between real and simulated contingent claim prices, consequently suggesting a choice for risk-neutral pricing measures in incomplete markets. In order to fulfill this aim, we constructed a model rich enough to describe stock prices but feasible for practice and connected to option prices. In this context, it is natural to exogenously specify different, suitable underlying asset price dynamics on a case-by-case basis.

The Esscher transform, invented by the Swedish actuary F. Esscher and introduced in Esscher (1932), is a time-honored tool in actuarial science for approximating the distribution of the aggregate claims of a portfolio. It consists of an exponential tilting procedure. More recently, it has been used as a premium calculation principle, see Van Heerwaarden et al. (1989), in option pricing, see Gerber and Shiu (1994), and also in pricing defaultable assets, see Lee and Rheinländer (2012). In our financial setting, the agent has the option to invest in a financial market via admissible strategies. Hereby we exclude strategies leading to arbitrage opportunities. The corresponding theory has been developed by Kallsen and Shiryaev, see Kallsen and Shiryaev (2002). In Benth and Schmeck (2014), the authors used an Esscher transform incorporated in a two-factor model to derive futures prices in electricity markets. Furthermore, pricing methodology for weather derivatives in a specific two-factor model is established in Hell et al. (2012).

The idea of calibration is to consider a set of liquid option prices, and to find a market martingale measure such that the expected values of the option payoffs are as close as possible to the observed prices. This approximation problem is typically ill-posed, and one has to include a regularization term, we opted for an entropic penalty term in this regard. A general exposition about the calibration method can be found in Cont and Tankov, see Cont and Tankov (2004a).

Section 2 and Section 3 are divided into a theoretical and a numerical part. The second section is devoted to the geometric Esscher measure and Laplace cumulant processes. In this part, we modeled the log–prices of the stock with a process (introduced in Klüppelberg et al. (2004)) and present a sufficient condition for the existence of such a measure. Assuming the driving Lévy process to have a (normal inverse Gaussian) distribution, which is infinitely divisible and thus corresponds to a Lévy process, we explain the original procedure—relying on the canonical representation theorem for semimartingales—followed by simulating the paths of the stock pricesunder the martingale measure. We pinpoint that, as Lemma 1 shows, the choice of the distribution in the model is crucial, since it allows for generating the risk-neutral trajectories of the underlying asset price.

In the third section, the calibration method is explained; using the fundamental concepts of relative entropy of distributions and Lévy processes on the Skorohod space (presented in Appendix E), we chose a martingale measure under which the dynamics of the stock prices follow an exponential Lévy process. In this part we mainly follow Cont and Tankov (2004a), even if the mathematical structure was refined and generalized, and the numerical approximation machinery was tailored to our goals.

In order to make the readers familiar with the theory and the notation that stands behind the main concepts of these two methods, in the appendix we also present a construction of the distribution and some essential results on Lévy processes, highlighting the connection with the characteristics of semimartingales.

The main point of the present paper is as follows: if there are many liquid options around, like plain vanilla calls and puts on liquid stocks, we would expect the calibration method to perform best, therefore, we chose it as the benchmark method. However, in new financial markets, like insurance derivatives, cryptocurrencies, energy, or electricity markets, there are often only a few derivatives or any at all available, or the underlying (like electricity) is difficult to trade in since it is not storable. In these cases the calibration method is not implementable, and there is not much choice other than to use the Esscher method which has been done, e.g., in the book by Benth, Benth, and Koekebakker about electricity and related markets, see Benth et al. (2008). Besides that, there are few, if at all, studies about practical implementation of hedging strategies in incomplete markets, therefore our study fills a gap in this direction. Our main result thus is that while the Esscher martingale measure based pricing method in a liquid market does underperform the calibration method, as is to be expected, it does so only by less than 5%. So it might be a feasible choice of method in new financial markets.

2. Esscher Measure Method

In this section, the dynamics of the stock prices are introduced and sufficient conditions for the existence of the Esscher measure, which was used to simulate European call options prices, are established. We refer to Appendix D for a brief summary of the theory, which is necessary to construct the geometric Esscher measure. In the following, we use notation that can be found, e.g., in the books (Rheinländer and Sexton 2011; Shiryaev and Jacod 2003), as well as references therein.

2.1. The Model

On a probability space we introduce a driving, -valued Lévy process with generating triplet with respect to a truncation function h (see Appendix B and Appendix C). We endow this space with , the augmented filtration of L. Define the dynamics of the spot prices by the process , where with the log-prices which follow a process, introduced in Klüppelberg et al. (2004):

The volatility process is given by

with and an adapted, right-continuous with left limits (RCLL) process defined by

where . We recall that a process is said to be RCLL if it has, almost surely, right-continuous trajectories with left limits. Although is a left-continuous process, as shown by (2), we use with the aim to highlight that we are working with a process which is adapted and left-continuous, therefore predictable.

For an adapted process modeling the interest rate, the discounted spot price process is given by , where . Thus, we consider the process , where for every , whose dynamics follow . At this point, we can express and we want to find a process such that is a –local martingale: denotes the geometric Esscher measure, or Esscher martingale transform, for the exponential process (see Appendix D).

Remark 1.

From (1), it is clear that G jumps at the same times as L does, and for every . For and , the measure associated with its jumps is

Furthermore , hence , meaning that

Theorem 1.

Let be such that is exponentially special and is a uniformly integrable martingale. If also is exponentially special and θ satisfies

for every , then is a -local martingale.

Note that is a 1-dimensional process, thus the geometric Esscher measure is unique.

Proof.

Let

and . By Remark 1, we get

Taking into account Lemma A1 in Appendix D, which provides

and considering that and , we obtain the characteristics of under P with respect to h:

The next lemma provides us with the candidate solutions to Equation (3) when L follows a distribution (see Appendix A).

Lemma 1.

Let be a -distributed Lévy process with parameters and define the truncation function If a process such that

fulfills Equation (3), then for every we have

with .

Proof.

Since , we apply (A6) and (A9) (see Appendix A and Appendix B) to obtain

where and Using (A5), we get

for . Proceeding as in the proof of Theorem 1, we have

Since , we expand on the chain of equalities in (8):

where the last equality is obtained by combining (5) and (7). At this point it remains to find the possible solutions for every to the equation

which can be written as Squaring both sides we get

and repeating once again the same operation of squaring we end up with an equation of second degree in :

where . Computing algebraically the solutions of (10) we get the expressions in (6). □

We have empirically tested both possible branches of solutions in (6), and we have chosen

to run the simulation because it prevents the risk-neutral dynamics from “exploding”, i.e., from skyrocketing to unrealistically high prices in a short time.

Remark 2.

Unfortunately, it does not seem possible for us to prove, from an analytical point of view, that either candidate solution in (6) solves (3), i.e., that it is a true solution. What the simulations suggest is that only the process in (11) is indeed a solution of (3). This insight is confirmed by the numerical experiments to a greater extent. In fact, it turns out that both processes satisfy Condition (5). However, makes the right hand side in (9) negative, and this implies that it does not solve (3). On the contrary, the process —the one we pick in (11)—makes such term positive, hence it solves (3), indeed.

2.1.1. Simulation of the -Dynamics

The goal of this section is to carefully describe a procedure to generate the risk-neutral dynamics of the underlying asset price. This allows us to compute the simulated European call option prices with the Monte Carlo method.

Let represent the constant annual interest rate. We assume that the driving Lévy process L is -distributed and that the hypothesis of Theorem 1 hold (with respect to the truncation function ). Using the R-package yuima (see Iacus 2011) we estimate the parameters of the model from the time series of the underlying asset log-prices. Next, we simulated a sufficiently large number of paths of the variance process with the found parameters: by (11), from each of them we can get a trajectory of . The issue reduces to generating the paths of G, but note that, after the change of measure, L is not a Lévy process anymore because . Consequently, G is not a process under the martingale measure. Then, in order to simulate its trajectories we use the canonical representation for semimartingales (Shiryaev and Jacod (2003), Chapter II, Theorem 2.34): for a d-dimensional semimartingale with characteristics relative to the truncation function h, it holds:

The symbol 🟉 denotes the integration with respect to a random measure: we refer to (Shiryaev and Jacod (2003), Chapter II, Section 1) for an extensive study of this topic. For the reader’s convenience, we provide the basic definition.

Definition 1.

Let μ be a random measure on and be measurable function with respect to the product σ-algebra , where denotes the optional σ-algebra on . The integral process is defined by

For an arbitrarily chosen , fix the truncation function for , and let be the corresponding generating triplet of L. From the proof of Theorem 1, specifically from (4), we readily get the characteristics of G under P, and invoking (A12) and Remark A2 in Appendix D we find them under :

We now represent G by (12), noting that and since . As regards the term , we expand on the computations in (13), getting

and obtain the variables of the process B by

At this point we need to approximate a trajectory of the process . In order to do so, we neglect the contribution of the jumps of G with absolute value smaller than , focusing just on the term

which in turn cancels out with one of the addends defining B. Heuristically speaking, in this approach we are assuming that the small jumps of the underlying asset price do not contribute to the determination of the option value in a significant way. However, we may refer to Asmussen and Rosiński (2001) for a more sophisticated procedure taking into account the variation of such small jumps in the case of Lévy processes.

Finally we concentrate on the term : we simulate its paths similarly to the Lévy–Itô decomposition theorem (see Sato 1999, Theorem 19.2). According to this result, if is a Lévy process with generating triplet and for , then is a compound Poisson process with constant and distribution

Thus, we take a nonhomogeneous Poisson process with time-varying intensity

and impose the time-varying jumps sizes to follow

The jump times of this process have been simulated by the thinning algorithm described in Lewis and Shedler (1979).

Denote by N the number of iterations we run and by , for , the corresponding, simulated trajectories of the spot price under the pricing measure . We obtain the value of an European call option with strike K and maturity T following the Monte Carlo method, i.e., computing the sample mean of the vector of components

2.1.2. Empirical Results

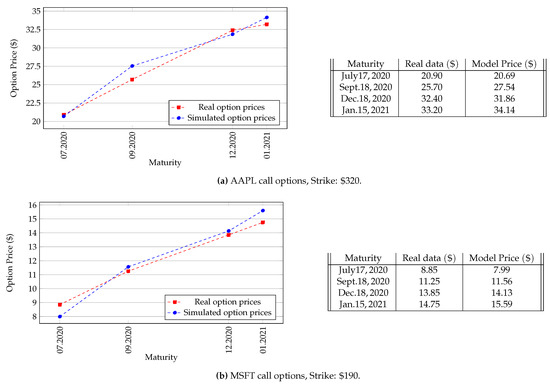

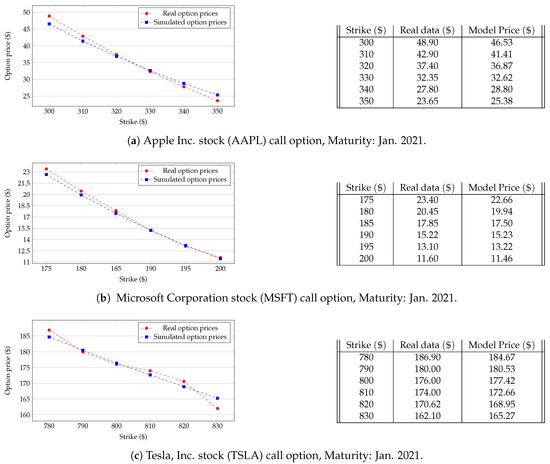

We have empirically tested the Esscher method on the prices of call options on Apple Inc. stock (ticker symbol: AAPL) with fixed strike at . In Figure 1a, the simulated option prices are shown as function of their maturities. The average of the absolute values of percentage difference is .

Figure 1.

Numerical experiments for the Esscher method.

Furthermore, we applied this method to the prices of call options on Microsoft Corporation stock (ticker symbol: MSFT) with strike : we plot the outcomes in Figure 1b. In this case, the mean of absolute values of percentage difference settles down at .

Finally we report the results of a test on call options with strike with Tesla, Inc. (ticker symbol: TSLA) as underlying stock. In Figure 1c we can notice a big discrepancy between the real price and the predicted value for the shortest-term maturity taken into account, the latter being smaller than the former. However, if we neglect this first term we recover a result in line with the previous experiments, namely an average for the absolute values of percentage difference of .

In all the three cases, we set the number of Monte Carlo iterations and we used the time series of the prices associated to the trading year before 19 February 2020, to estimate the parameters of the model (see Section 2.1.1). Therefore, the simulations were run prior to Apple’s stock split (on 28 August 2020) and Tesla’s stock split (on 31 August 2020).

Remark 3.

The real data was obtained from https://old.nasdaq.com, where American options are traded. Although our approximation generates the prices in an European model, it can be accepted as meaningful since:

- the analyzed derivatives have short-term maturities, so we are allowed to ignore the dividend yield (however, TSLA does not pay dividends);

- the time values of the options were always positive, implying that it is convenient to sell the option rather than exercising the call right.

3. Calibration with Entropic Penalty Term Method

In the Esscher method, the density process is completely defined by the spot prices: this is an intuitive drawback in liquid markets, because it does not use all the available information (e.g., the time series of derivative prices). This is a motivation to consider the Calibration Method, which consists in modeling the spot prices dynamics directly under a martingale measure “chosen” by the market.

3.1. The Model

We start the practical analysis by taking into account a driving, -valued Lévy process with generating triplet on a probability space endowed with the augmented filtration of L, which satisfies the usual conditions and is denoted by . We describe the stock prices with an exponential Lévy model: with and representing the constant annual interest rate. The discounting process reduces to the deterministic function Since we need Q to be a martingale measure for S we require:

- (i)

- there exists a such that ;

- (ii)

- .

With these assumptions, Remark A1 in Appendix B proves that is a martingale with for every . Considering the discounted spot prices process , defined by , we can state that it is a Q-martingale with constant expectation equal to .

In our discussion the driving Lévy process L will be a pure jump process, so its generating triplet simplifies as . In particular, due to assumption (ii) we get the next relation:

Assume that there are N European call options with fixed maturity T available in the market, and for each let and be the strike price and the observed price of the j-th derivative, respectively. It is convenient to consider the quantities . In this setting, S is the price process of the underlying asset. Since Q is a martingale measure for S, we can use it to price options: . Denoting by the pushforward distribution on generated by we have

Thus, knowing the Lévy measure , the whole generating triplet could be recovered and therefore the option prices computed.

The reasoning which leads the calibration is choosing such that is “close” to for any . Hence we pick the Lévy measure of the model by a least-squares procedure:

Since the problem expressed in (15) is ill posed (see Cont and Tankov 2004a, Chp. 13), we introduce a regularization term. Let be a, pure jump, driving Lévy process with generating triplet statistically estimated from the time series of the underlying asset price. Furthermore, let and be the distributions on the Skorohod space generated by and L, respectively, which are supposed to be equivalent on for every (see Appendix E). We use the relative entropy as a measure of the distance from , so that by Remark A3 the issue is reduced to solving the optimization problem:

for . The term is a regularization parameter: the higher it is, the more we trust the initial distribution and the less importance we give to calibration. The existence of a solution to (16) has been studied, among others, in the paper Cont and Tankov (2004b). We are going to relax the assumptions in (16), considering the minimization in the set of the Lévy measures equivalent to .

3.1.1. Numerical Approximation

The goal of this section is to describe in each and every detail a discretization procedure that allows us to tackle the optimization problem in (16). To this aim, it is necessary to express the objective functional in (16) as a function of the masses of the discretized Lévy measures. The steps of our argument are the following:

- I.

- estimate the parameters of the prior Lévy process from the time series of log–returns;

- II.

- introduce a discretization grid for the prior Lévy measure and the driving Lévy measure (in what follows, the points of such a grid are denoted by ). Their discretized versions are denoted by and , respectively;

- III.

- compute the discrete version of the entropy term in (16) as a function of the masses of ;

- IV.

- V.

- calculate explicitly the derivatives of the discretized objective functional to speed up the simulations;

- VI.

- choose the regularization parameter .

Fix a maturity T and define the grid , , with : these points represent the log–strike prices of the options available on the market. Moreover, from the time series of the log–returns we obtain the parameters of the historical, -distributed Lévy process by a maximum likelihood procedure using the R-package ghyp. Note that, in this case, one can select any pure jump, infinitely divisible distribution: we opt for the NIG by analogy with the Esscher’s method, and our choice is satisfactory, as the final goodness of fit between real data and model prices shows. First we introduce a discretization grid consisting in the points , with , which constitutes a partition of the interval for some , and then we approximate the Lévy measure of with the discrete version , where denotes the Dirac measure at a point and

Now we take into account another measure which has the same mass points as the previous one: with for every . We note that the calibrated measures and are equivalent, but and the prior are not. We understand the measure as the discretized Lévy measure of the driving, pure jump Lévy processes . We now want to compute the Radon–Nikodym derivative with the aim to explicitly express the entropy term of (16) in the discrete version

Set and define the function

Following the Carr and Madan approach (see Carr and Madan 1999, Section 3.2) for further details), we are able to to express the quantity as a function of . The option price is not an integrable function, as a swift application of Lebesgue’s convergence theorem shows that it converges to as . Therefore, we focus on the modified time value , defined by We suppose that and its inverse Fourier transform are integrable, so by inversion (see, e.g., Rudin 1987, Theorem 9.11) we have

Fix ; we first analyze the term

In a similar way we get

This provides the following expression for :

The assumption (ii) ensures that so we finally obtain

The insight here is to use the Fourier transform and its inverse to estimate the values for every . Hence we fix a point and introduce the inverse Fourier transform

Under suitable conditions which allow us to switch the order of integration we have

We turn our attention on the computation of the first term of the sum (19). An explicit calculation of the inner integral (respect to the Lebesgue measure) of such addend, indicated by , gives

The same strategy allows us to compute the inner integral of the second addend in (19), as well. Precisely, for every we get

Therefore we are able to represent the inverse Fourier transform as

By the definition of in (A8) (see Appendix B), substituting the discrete version for the Lévy measure associated to L, as a consequence of (14) we get, for every ,

With the aim to approximate at the points , for , we construct a new, uniform grid with mesh d containing the log-strike one. Specifically, fixed , we set

for , with , which is the size of the discretization interval. We carry out our construction so that for every and there exists a such that . We eventually introduce the points of the discretization grid as

We then compute

where are chosen by the trapezoidal rule, i.e.,

Therefore, knowing for , we can use a fast Fourier transform (FFT) to estimate the values , for , and, due to the symmetry of the grid, an inverse discrete Fourier transform to get for . Thus, we reduce the optimization problem (16) to the minimization in of the objective functional:

The optimization is run under the L-BFGS-B algorithm, so we compute the derivatives of to speed it up. We focus on deriving the first addend in (23), since calculating the entropic term is straightforward. Denote by the argument of the exponential in (22) and define

Under suitable integrability condition, for every and we have

Direct calculation from (18) leads, for every and , to

Summarizing, we can numerically calculate the derivatives of :

for any .

The regularization parameter should be eventually determined; to this aim, we follow a procedure loosely inspired by the Morozov discrepancy principle (see the classical Morozov (1966)). We start off by minimizing the quadratic pricing error (15), ignoring the entropy term and using the discretized Lévy measure of as starting point. The value of the functional at the found minimum is interpreted as the distance between the market and the selected model class. After that we consider the bid–ask spread of the options on the market and denote by its Euclidean norm. The absolute value of the difference between these two quantities is then allowed to be slightly greater, although it must maintain the same order of magnitude. This leads to the introduction of another term , where c is a positive constant to be picked. At this point the functional in (16) is strictly increasing in , so we choose the regularization parameter as follows:

For our applications, taking has proven to be a satisfactory choice in terms of goodness of fit.

3.1.2. Empirical Results

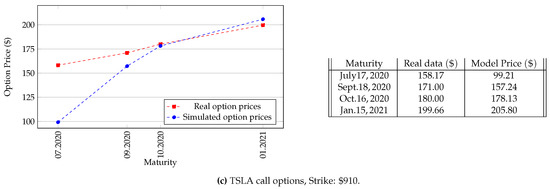

The final step is to empirically apply this method on prices of real-traded options. In particular, we have tested it with derivatives on the same stocks as those considered for the Esscher’s method. In order to estimate the parameters of the historical Lévy process, we used the same time series of log–prices as those of the Esscher’s method (see Section 2.1.2) All the call options under scrutiny expire in January 2021: 11 months from the time of simulation.

In the case of call options on Apple Inc. stock (AAPL) we obtained an average of the absolute values of percentage difference of : Figure 2a displays the results of such implementation. As regards call options on Microsoft Corporation stock (MSFT), the absolute values of percentage difference is and the results are shown in Figure 2b. Finally we calibrated our method to the prices of call options on Tesla, Inc. stock (TSLA): Figure 2c shows the outcomes. Here the mean of absolute values of percentage difference settles down at .

Figure 2.

Numerical experiments for the calibration method.

This time we retrieved the real prices from https://finance.yahoo.com, but the same considerations as Remark 3 apply.

4. Conclusions

The main purpose of this research is to quantify the performances of two option pricing methods in a liquid market like NASDAQ. The first approach is based on the Esscher measure, the second one on the calibration to real-traded call option prices with an entropic penalty term.

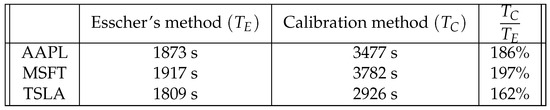

Our experimental analysis shows that, from a computational point of view, the Esscher method with Monte Carlo iterations is far faster than the calibration method: the table in Figure 3 reports the exact execution times that we have obtained with an Asus ZenBook UX31A. This fact is especially noticeable when we need to simulate the prices of options with different maturities and same strike. On the other hand, the calibration method allows generating the entire option chain for a fixed maturity with great precision. Moreover, it is more stable than the previous one, as it provides results closer to real data for a larger range of stock prices.

Figure 3.

Computational times (in seconds) of both methods (with an Asus ZenBook UX31A).

Comparing averages of absolute values for percentage difference between real and simulated prices, the calibration procedure offers better outcomes than Esscher’s, with the only exception of AAPL call options, where the latter outperforms the former by approximately 42 basis points. Nevertheless, the Esscher method only needs the historical time series of the underlying asset price to be applied, so it is feasible also in markets with few derivatives. This study shows that the Esscher measure is an appealing and efficient solution to price call options in illiquid—or low liquid—financial markets.

5. Future Research

Considering the future work on the subject, one of the directions worth investigating is the Linear Esscher measure method. The importance of focusing on this approach is given by its intrinsic link to the minimal entropy Hellinger martingale measure, as indicated by Rheinländer and Sexton in (Rheinländer and Sexton 2011, Chp. 9), and, in much more detail, by Choulli and Stricker in Choulli and Stricker (2006). Moreover, it would be interesting to extend our study to other asset classes like metal futures, and to compare it with the results obtained in Chen (2011).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and T.R.; methodology, T.R.; software, A.B.; validation, A.B., D.R. and T.R.; formal analysis, A.B., D.R. and T.R.; investigation, A.B., D.R. and T.R.; resources, A.B., D.R. and T.R.; data curation, A.B., D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B., D.R.; writing—review and editing, A.B., D.R. and T.R.; visualization, A.B., D.R.; supervision, T.R.; project administration, T.R.; funding acquisition, T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access Funding by TU Wien. This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dan Chen for valuable comments. The authors acknowledge TU Wien Bibliothek for financial support through its Open Access Funding Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

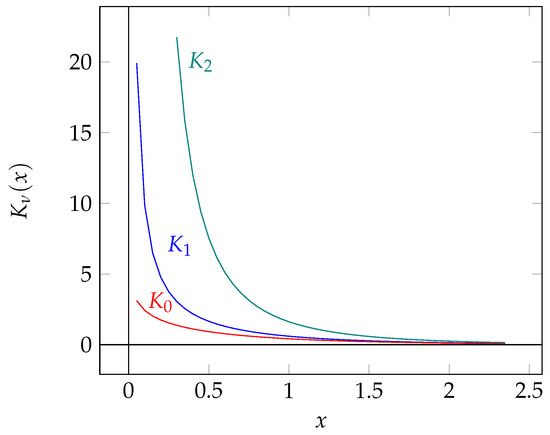

Appendix A. Normal Inverse Gaussian Distribution

In our work, we extensively use the distribution, because it provides a good fit for the analyzed data. A probability measure on is said to be with parameters , where and , if it has the following density:

with that denotes the modified Bessel function of the third kind with index 1 and . For a definition of we refer to Abramowitz and Stegun (1970). The next procedure is the classical construction of such a distribution.

A probability measure on is said to be a generalized inverse Gaussian (GIG) distribution with parameters if its density with respect to the Lebesgue measure is

In order to show that is a density function, we need the following representation for (Watson 1966, Formula (8), p. 182), the modified Bessel function of the third kind with index :

The computation of the next integral allows us to find the normalization constant in (A2):

where in the second equality we made the substitution . Since in from (A3), we can conclude that is actually a density function on .

Figure A1.

are the modified Bessel functions of the first three, nonnegative, integer orders, respectively.

Let us fix two other parameters such that . For any we denote by the density of the probability measure on generated by a random variable . It is possible to introduce a new distribution on considering the following function:

where in the last but one equality we made the substitution and in the last we used (A3).

A straightforward application of Tonelli’s theorem shows that is a density function: the corresponding probability measure on is called Generalized Hyperbolic distribution.

We recover the density (A1) taking in (A4). In fact, for every , it results and the representation (Abramowitz and Stegun (1970), Formula ())

which holds for every , enables us to conclude

As a particular case of Generalized Hyperbolic distribution, the probability measure is infinitely divisible (see, e.g., Barndorff-Nielsen and Halgreen 1977; Eberlein and Hammerstein 2004). The moment generating function for a random variable is given by

and its generating triplet (see Appendix B for the definition of this concept) is given by

For an explicit calculation, we refer to the paper Barndorff-Nielsen (1998).

Appendix B. Cumulant Function of Lévy Processes

Fix a probability space . It is well known that, if is a Lévy process, then is infinitely divisible for every . On the other hand, for every infinitely divisible probability measure on , there exists a Lévy process , which is unique up to identity in law, such that .

The Lévy–Khintchine representation theorem states that, given an infinitely divisible distribution on , its characteristic function can be written as:

where , , is a measure on satisfying

and A is a symmetric, positive semidefinite matrix. The representation (A7) of by is unique and the triplet is called generating triplet of the distribution . The generating triplet of a Lévy process is the generating triplet of .

Note that it is not necessary to take to have integrability in (A7). In fact, let be a bounded function, with in a neighborhood of 0: we call it a truncation function. Since, for every , in a neighborhood of 0 we have and, further, , for some positive constant C such that in , if we put component wise, then the Lévy–Khintchine formula with respect to h becomes:

We note that only depends on the choice of the truncation function.

It is possible to “extend” the argument of the exponential function in (A7), called characteristic exponent and denoted by , to a subset of . Precisely, taking into account the set

we can define the function as follows:

where . We readily note that for every and the following equality holds: . In this sense extends to a subset of . We pinpoint that, in this paper, we set , so is not the -Hermitian inner product. Theorem in Sato (1999) affirms that, if is a Lévy process generated by , then

we call the cumulant function of X. As we have previously done, we can introduce a truncation function h and express in , where

Remark A1.

Let be a -valued Lévy process defined on a probability space , Ψ be its cumulant function and be such that for some . By Theorem in Sato (1999), this is equivalent to require that . We introduce the random variables

Note that is integrable, by assumption and the fact that is constant in Ω for every . Let us construct the minimal augmented filtration of X, i.e., for any , where is the natural filtration of the process and the collection of -negligible sets; obviously, M is -adapted. According to (Protter 2005, Chapter I, Theorem 31) is right-continuous, so it satisfies the usual conditions, as well. If we fix , then using (A9) and the properties of the Lévy-increments we see that M is a martingale with mean 1:

Definition A1.

Fix and let . The probability measure on , with on , defined by is called the Esscher transform of P with respect to θ. The density process is given by

Appendix C. Characteristics of Semimartingales

The aim of this section is to generalize the concept of generating triplet of a Lévy process to semimartingales. Here we mainly follow (Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chapter II).

We start off by fixing a stochastic basis , with which satisfies the usual conditions. Given two stopping times , the stochastic interval is the random set

and .

Definition A2.

A random set A is called thin if it is of the form where is a sequence of stopping times.

It is important to observe that the sections , for , are at most countable when A is a thin set.

Theorem A1.

If is a RCLL, adapted process, then the random set is thin.

We refer to (He et al. 2018, Theorem 3.32) for a proof. Thanks to this result we can easily introduce the next concept.

Definition A3.

Let be an adapted, RCLL, -valued process. The measure on defined by

where denotes the Dirac measure at a point , is called measure associated with its jumps.

We now consider a process which is a d-dimensional semimartingale, highlighting that we restrict our attention to RCLL and -adapted semimartingales. Let h be a truncation function; using the measure it is possible to derive the characteristics of X (see Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chp. II, Definition 2.6), which we denote by the triplet . They are defined up to a P-null set and only B depends on the choice of h.

Every Lévy process—once we endow the probability space in which it is defined with its minimal augmented filtration—is a process (a RCLL, adapted process which starts at 0 and has independent and stationary increments), which in turn is a semimartingale. Thus, considering a Lévy process with generating triplet relative to a truncation function h, we can apply (Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chp. II, Corollary 4.19) together with the uniqueness of the Lévy–Khintchine representation to express its characteristics as

Appendix D. Laplace Cumulant and Geometric Esscher Measure

On a stochastic basis , with the filtration which satisfies the usual conditions of right-continuity and completeness, we define a d–dimensional semimartingale , i.e., a process which can be decomposed as , a sum of a local martingale M and a process A of locally finite variation which is called drift, or additive compensator, of the semimartingale, and with characteristics relative to a truncation function h (see Appendix B for the definition). In particular, a special semimartingale is a semimartingale where its finite variation part is predictable; such a special semimartingale has a unique semimartingale decomposition. In view of (Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chp. II, Proposition 2.9) we can assume, without loss of generality, that identically. An exposition on semimartingale characteristics is outside of the scope of this paper, for this we refer to Shiryaev and Jacod (2003).

Now we introduce the stochastic logarithm and the stochastic exponential, denoted by and , respectively. The symbol · denotes stochastic integration, the exact meaning can vary according to the context. Let X be a semimartingale; the set of stochastic processes which are integrable with respect to X is denoted by . This notion is quite intricate, and it is not the purpose of this article to give an overview on the theory of stochastic integration. For this, we refer to (Protter 2005, Chp. IV, Section 2). The solution of the stochastic integral equation

is denoted as the stochastic exponential of the semimartingale X. Here, the process is defined by for , with . Conversely, if Y is a semimartingale such that both Y and do not vanish, then the process

denoted by , is called the stochastic logarithm of Y, and is the unique semimartingale such that

For a detailed exposition of these concepts we refer to (Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chp. II, Section 8).

Definition A4.

Let be an admissible strategy such that is exponentially special, i.e., is a special semimartingale. The Laplace cumulant of X at θ is the additive compensator of the real-valued, special semimartingale

The modified Laplace cumulant of X at θ is the process

Note that the additive compensator of the process

is predictable because is special and is predictable. Therefore, is a special semimartingale and the definition of is well posed. As far as is concerned, recalling (Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chp. III, Theorem 7.4) we have

Thus, the stochastic exponential in (A10) is strictly positive and the process is well defined, as well.

If is exponentially special, then is its exponential compensator, see (Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chp. III, Theorem 7.14). This means that the process , defined by , is a local martingale starting at . We now recall the concept of uniform integrability.

Definition A5.

A non-empty set Φ of real-valued random variable defined on a probability space is uniformly integrable if

Supposing that is a uniformly integrable martingale, then we can set , where a.s. and in as . It is straightforward to show that is the density of relative to P; besides, these two distributions are locally equivalent as .

The following result (Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chp. III, Theorem 7.18) establishes a necessary and sufficient condition such that the process is a -local martingale for every .

Theorem A2.

Let be such that is exponentially special and is a uniformly integrable martingale. Define

Then the processes are -local martingales if and only if is exponentially special and up to evanescence for every .

We call geometric Esscher measure, or Esscher martingale transform for exponential processes. For , in case the geometric Esscher measure exists, (Kallsen and Shiryaev 2002, Theorem 4.2) provides its uniqueness: this means that, if we find another process such that is a -local martingale, then .

We conclude with some technical results. Let be such that is exponentially special. By (Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chp. III, Theorem 7.4) and (Shiryaev and Jacod 2003, Chp. II, Proposition 2.9) we can write , where

The next lemma (Kallsen and Shiryaev 2002, Lemma 2.11) allows us to express the drift process as a function of the characteristics of the semimartingale.

Lemma A1.

Let be such that is a special semimartingale. Then its drift process , where

Finally, we use Girsanov’s theorem to compute the characteristics of X under —provided its existence—relative to the same h:

where . Note that

Remark A2.

For and , we have:

Moreover, as if the function is continuous in t, then is the null measure on , which implies that .

Appendix E. Lévy Processes on Skorohod Space and Relative Entropy of Distributions

Let be a probability space which carries a -valued, additive process with system of generating triplets . For every we define , where is the Skorohod Space, as and we introduce the -algebra . Now we are in the position to define a natural filtration on the measurable space , where . Since is an RCLL process, we set the map as , where , with for any . The function is measurable, since

and, for every and , we have

This enables us to construct the pushforward measure on , that is,

We now focus on the stochastic process defined on the probability space . Fix a cylinder set , i.e.,

for some and . By (A13), we have

Thus, and are identical in law, whence is an additive process with the same system of generating triplets as . Specifically, if were a Lévy process, then would inherit the temporal homogeneity, so it would be a Lévy process, as well.

Consider two Lévy processes and on the Skorohod space endowed with the filtration . The next theorem (Sato 1999, Theorems 33.1 & 33.2) provides us with conditions which ensure for any .

Theorem A3.

Let , be Lévy processes on with generating triplets and , respectively. Then the following properties are equivalent:

- (a)

- for every ;

- (b)

- the generating triplets satisfy: , .

Besides, considering the function defined by ,

In this case, chosen such that , there exists a process defined on which satisfies the following properties:

- (i)

- U is a P-Lévy process on with generating triplet

- (ii)

- for every ;

- (iii)

- for every .

An explicit expression of the process U, which is unique up to identity in law, can be retrieved in (Sato 1999, Theorem 33.2).

Definition A6.

Given two probability measures on a measurable space , the relative entropy of P with respect to is defined by

Recall that given two distributions on we have , with equality if and only if .

We finally present a theorem which explicitly computes the relative entropy of two equivalent Lévy processes in the Skorohod space as a function of their generating triplets.

Theorem A4.

Let , be Lévy processes on defined on with generating triplets and , respectively. Suppose that for every and choose such that

Assume also that for some , where . Then for every it results

Proof.

Let us fix a finite time horizon . For any , by assumption we have

We introduce the moment generating function where is the cumulant function of the Lévy process U, i.e.,

and the last equality is ensured by (A9) in Appendix B. Actually is well defined for too, with , by A3 in Theorem A3. We can see that is differentiable in with . Indeed, for every , and we can derive under integral sign since

At this point the dominated convergence theorem readily shows that

On the other hand, we introduce the function

Even in this case we can affirm that f is differentiable in its domain, with derivative provided by . In particular the following equality is true:

In fact, we can derive under the integral sign in (A15) as, for every , it results that , , with in a neighborhood of 0 for some constant which is independent of z. Moreover, for , with by Theorem in Sato (1999). Applying another time the Lebesgue’s convergence theorem we arrive at

Therefore

using the expression of in A3 of Theorem A3. Since for every (see A3 in Theorem A3) and

we obtain (A14) and complete the proof. □

Remark A3.

In the case of two -valued Lévy processes , with generating triplets and , respectively, under the hypothesis of the previous theorem (A14) reduces to

If we are dealing with pure jump processes (e.g., processes), the first term in the sum of the right-hand side is 0; if instead , then we have

restoring (Cont and Tankov 2004a, Proposition 9.10).

References

- Abramowitz, Milton, and Irene A. Stegun. 1970. Handbook of Mathematical Functions: With Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, vol. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Asmussen, Søren, and Jan Rosiński. 2001. Approximations of Small Jumps of Lévy Processes with a View towards Simulation. Journal of Applied Probability 38: 482–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barndorff-Nielsen, Ole E. 1998. Processes of Normal Inverse Gaussian Type. Finance and Stochastics 2: 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barndorff-Nielsen, Ole, and Christian Halgreen. 1977. Infinite Divisibility of the Hyperbolic and Generalized Inverse Gaussian Distributions. Probability Theory and Related Fields 38: 309–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benth, Fred Espen, and Maren Diane Schmeck. 2014. Pricing futures and options in electricity markets. In The Interrelationship Between Financial and Energy Markets. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 233–60. [Google Scholar]

- Benth, Fred Espen, Jurate Saltyte Benth, and Steen Koekebakker. 2008. Stochastic Modelling of Electricity and Related Markets. Singapore: World Scientific, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, Peter, and Dilip Madan. 1999. Option Valuation using the Fast Fourier Transform. Journal of Computational Finance 2: 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Dan. 2011. Three Essays on Pricing and Hedging in Incomplete Markets. Ph.D. thesis, The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), London. [Google Scholar]

- Choulli, Tahir, and Christophe Stricker. 2006. More on minimal entropy–Hellinger martingale measure. Mathematical Finance 16: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cont, Rama, and Peter Tankov. 2004a. Financial Modelling with Jump Processes. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Cont, Rama, and Peter Tankov. 2004b. Nonparametric calibration of jump-diffusion option pricing models. Journal of Computational Finance, Incisive Media 7: 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, Ernst, and Ernst August V. Hammerstein. 2004. Generalized hyperbolic and inverse Gaussian distributions: Limiting cases and approximation of processes. In Seminar on Stochastic Analysis, Random Fields and Applications IV. Berlin: Springer, pp. 221–64. [Google Scholar]

- Esscher, F. 1932. On the Probability Function in the Collective Theory of Risk. Skandinavisk Aktuarietidskrift 15: 175–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, Hans U., and Elias SW Shiu. 1994. Option Pricing by Esscher Transforms. Transactions of the Society of Actuaries 46: 99–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hell, Philipp, Thilo Meyer-Brandis, and Thorsten Rheinländer. 2012. Consistent factor models for temperature markets. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Finance 15: 1250027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Sheng-wu, Jia-gang Wang, and Jia-an Yan. 2018. Semimartingale Theory and Stochastic Calculus. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Iacus, Stefano Maria. 2011. Option Pricing and Estimation of Financial Models with R. New York: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Jeanblanc, Monique, Marc Yor, and Marc Chesney. 2009. Mathematical Methods for Financial Markets. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kallsen, Jan, and Albert N. Shiryaev. 2002. The Cumulant Process and Esscher’s Change of Measure. Finance and Stochastics 6: 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Klüppelberg, Claudia, Alexander Lindner, and Ross Maller. 2004. A Continuous Time GARCH Process Driven by a Lévy Process: Stationarity and Second Order Behaviour. Journal of Applied Probability 41: 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Young, and Thorsten Rheinländer. 2012. Optimal martingale measures for defaultable assets. Stochastic Processes and their Applications 122: 2870–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, PA W., and Gerald S. Shedler. 1979. Simulation of Nonhomogeneous Poisson Processes by Thinning. Naval Research Logistics Quarterly 26: 403–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, Vladimir Alekseevich. 1966. On the solution of functional equations by the method of regularization. Doklady Akademii Nauk 167: 510–12. [Google Scholar]

- Protter, P. E. 2005. Stochastic Integration and Differential Equations, 2nd ed. Stochastic Modelling and Applied Probability. Berlin: Springer, vol. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Rheinländer, Thorsten, and Jenny Sexton. 2011. Hedging Derivatives. Singapore: World Scientific, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, Walter. 1987. Real and Complex Analysis, 3rd ed. Mathematics Series; New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Ken-Iti. 1999. Lévy Processes and Infinitely Divisible Distributions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shiryaev, Albert, and Jean J. Jacod. 2003. Limit Theorems for Stochastic Processes. A Series of Comprehensive Studies in Mathematics; Berlin: Germany, vol. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Shreve, Steven E. 2004. Stochastic Calculus for Finance II (Continuous–Time Models). Springer Finance Textbooks. Berlin: Springer, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heerwaarden, Angela E., Rob Kaas, and Marc J. Goovaerts. 1989. Properties of the Esscher premium calculation principle. Insurance Mathematics and Economics 8.4 335: 261–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, George Neville. 1966. A Treatise on the Theory of Bessel Functions, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).