Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., A.K.G., R.M. and V.S.; methodology, S.S., R.M. and V.S.; software, S.S., R.M. and V.S.; validation, S.S. and V.S.; formal analysis, S.S., R.M. and V.S.; investigation, A.K.G., R.M. and V.S.; resources, A.K.G., R.M. and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S., A.K.G., R.M. and V.S.; writing—review and editing, A.K.G., R.M. and V.S.; supervision, A.K.G., R.M. and V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

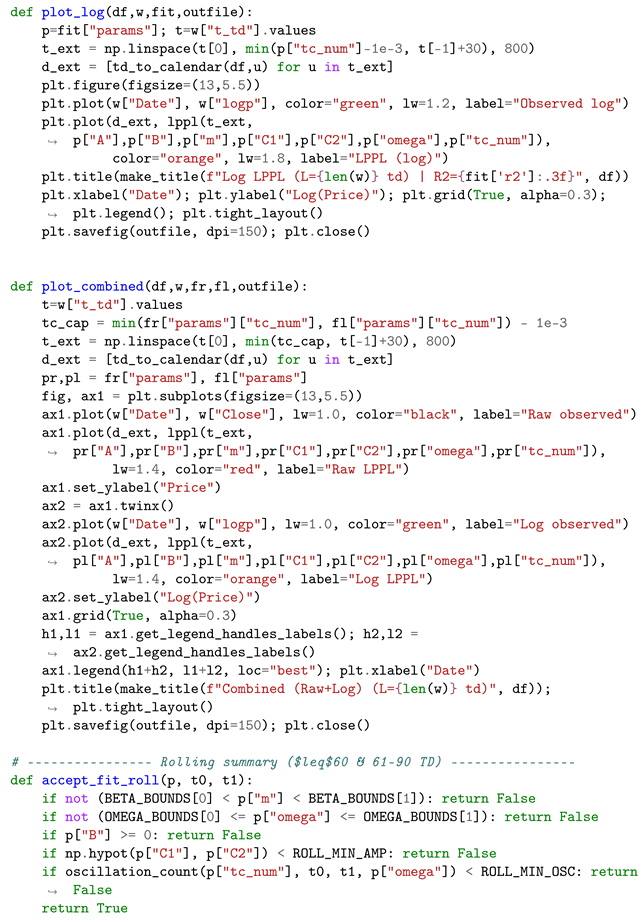

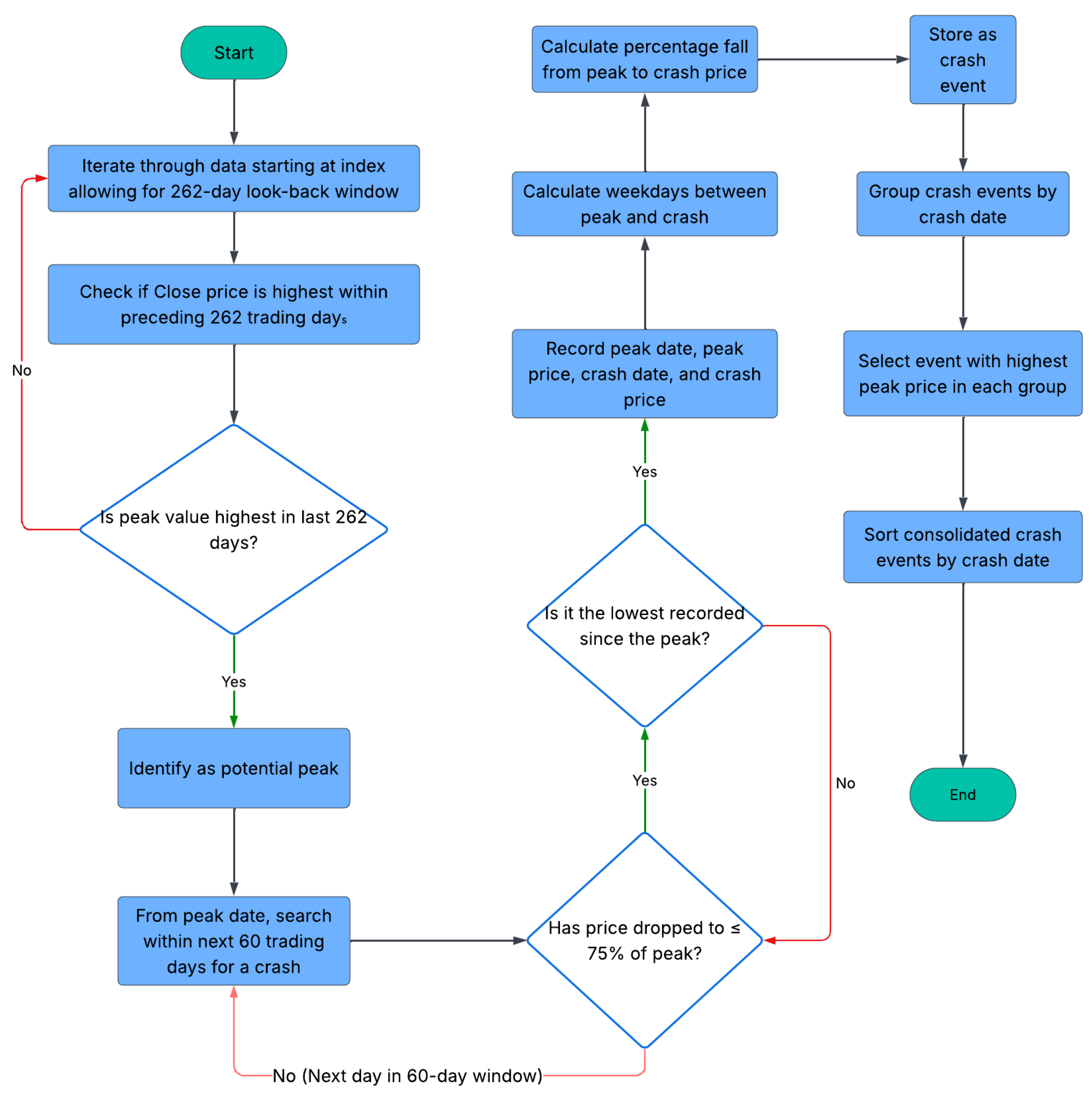

Figure 2.

LPPL pipeline flow chart used in this study.

Figure 2.

LPPL pipeline flow chart used in this study.

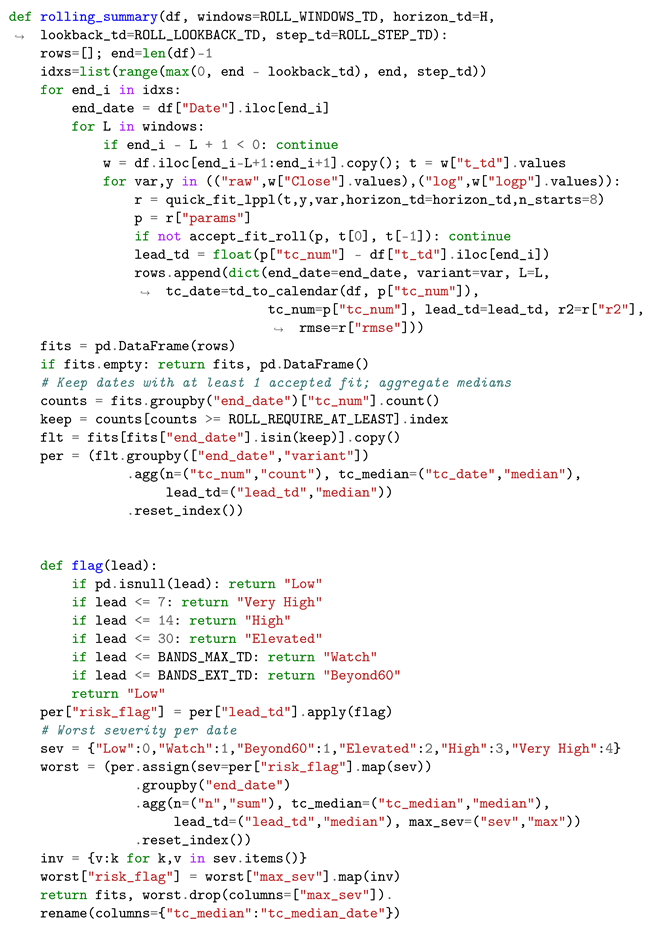

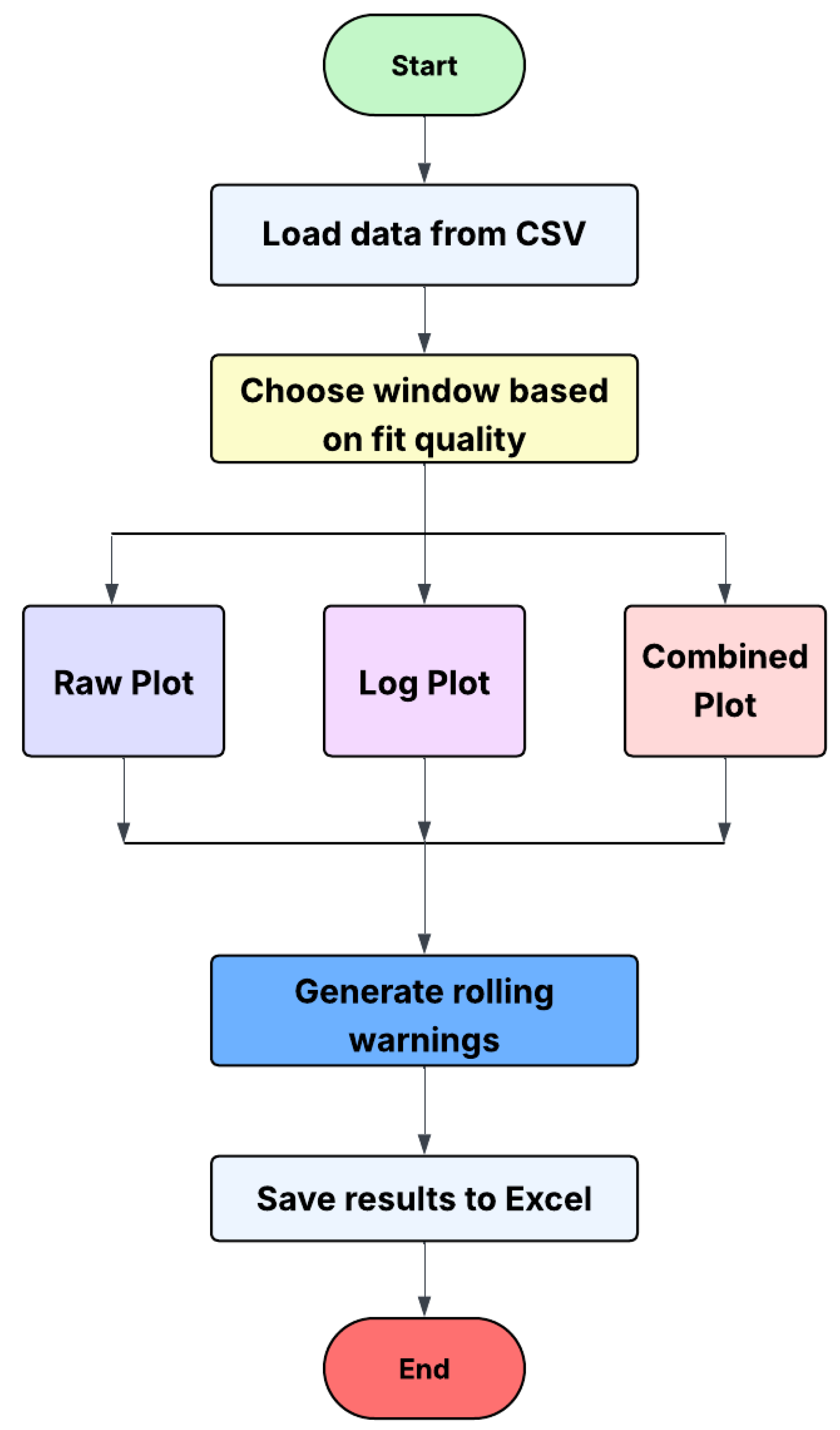

Figure 3.

Historical peak and crash dates identified in the three equity indices using the criteria of (

Brée and Joseph 2013). Panel (

a) shows the IPC (Mexico), Panel (

b) displays IBOVESPA (Brazil), and Panel (

c) shows the NYSE Composite (USA).

Figure 3.

Historical peak and crash dates identified in the three equity indices using the criteria of (

Brée and Joseph 2013). Panel (

a) shows the IPC (Mexico), Panel (

b) displays IBOVESPA (Brazil), and Panel (

c) shows the NYSE Composite (USA).

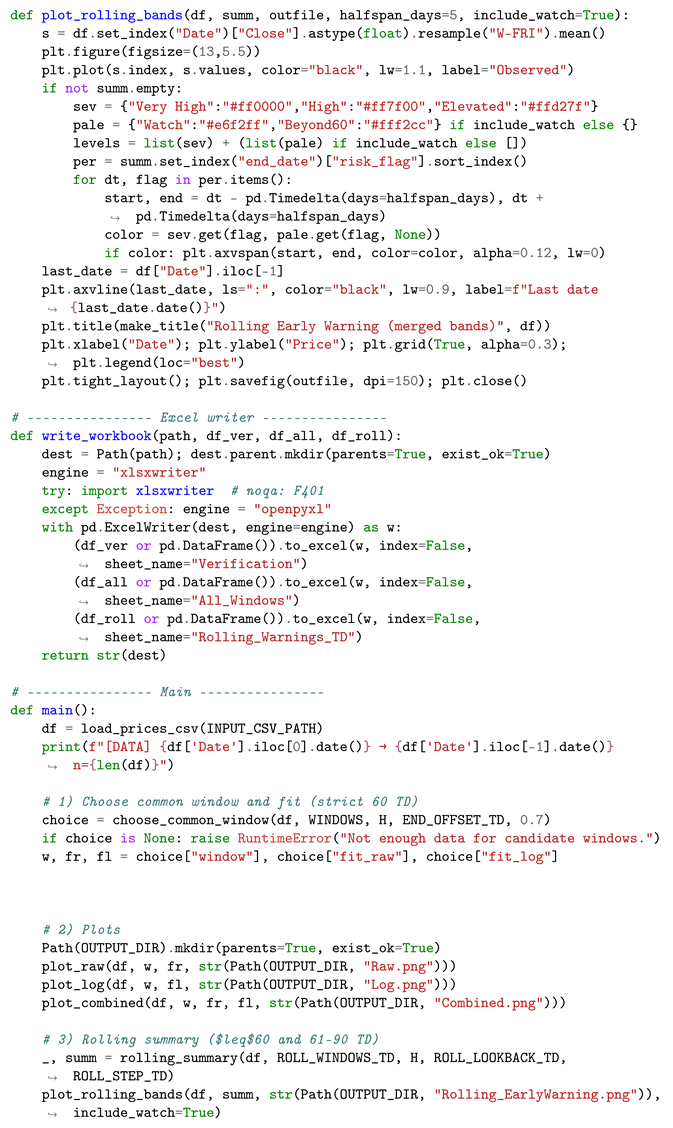

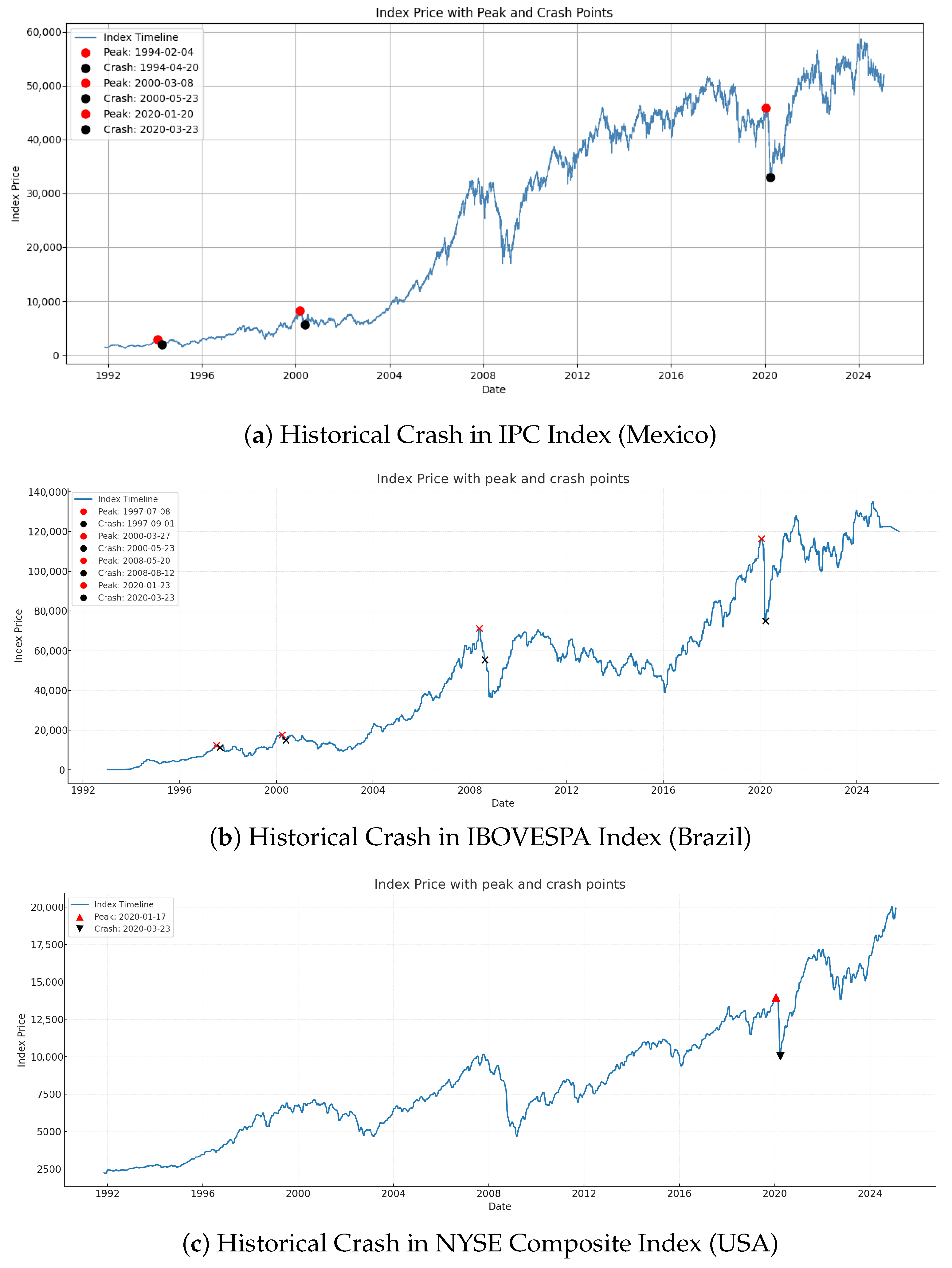

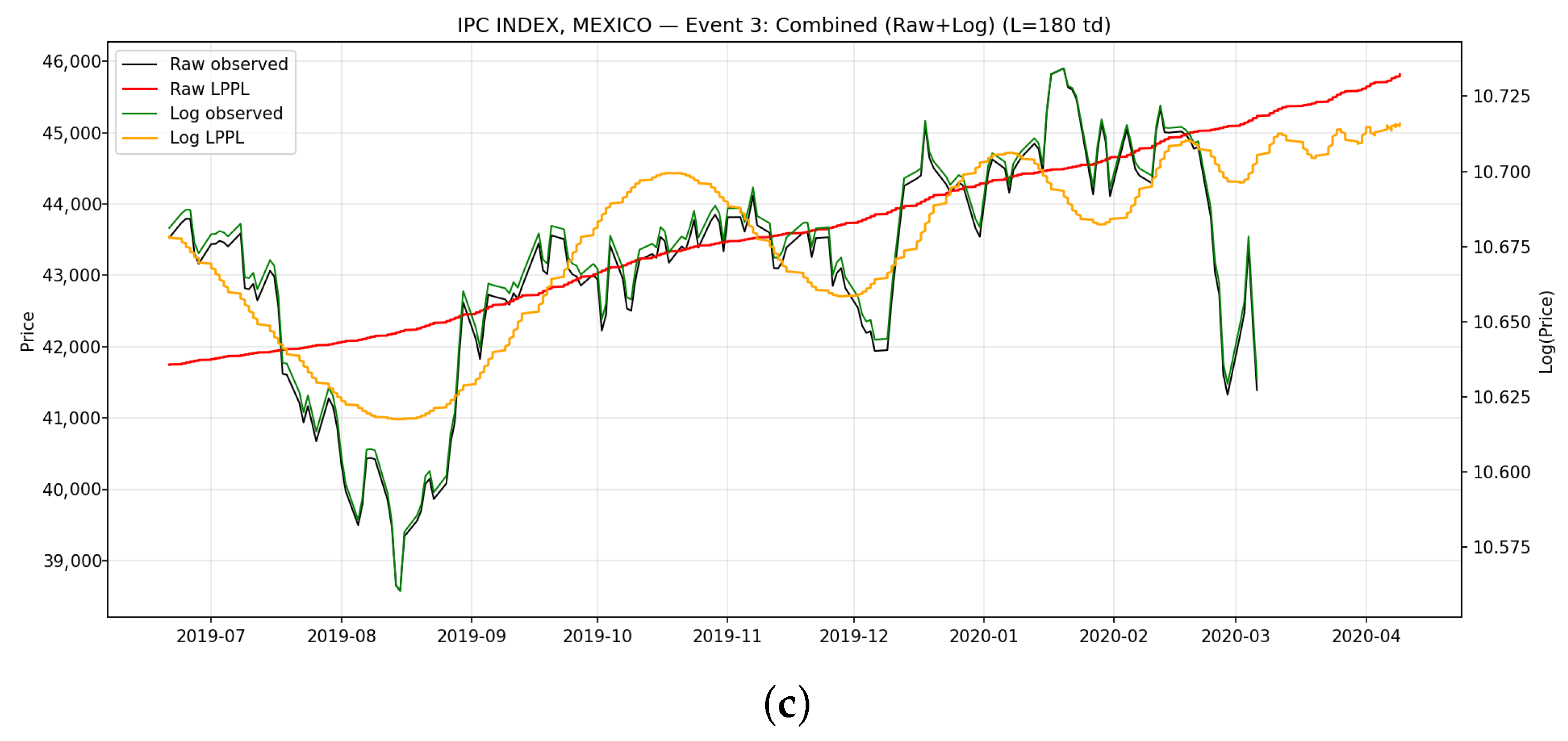

Figure 4.

Combined (Raw + Log) LPPL fits for IPC/BMV, Mexico across Events 1–3. Each panel overlays the raw and log-LPPL trajectories with observed prices, showing the approach toward the estimated critical region. (a) IPC Mexico—Event 1 (Combined); (b) IPC Mexico—Event 2 (Combined); (c) IPC Mexico—Event 3 (Combined).

Figure 4.

Combined (Raw + Log) LPPL fits for IPC/BMV, Mexico across Events 1–3. Each panel overlays the raw and log-LPPL trajectories with observed prices, showing the approach toward the estimated critical region. (a) IPC Mexico—Event 1 (Combined); (b) IPC Mexico—Event 2 (Combined); (c) IPC Mexico—Event 3 (Combined).

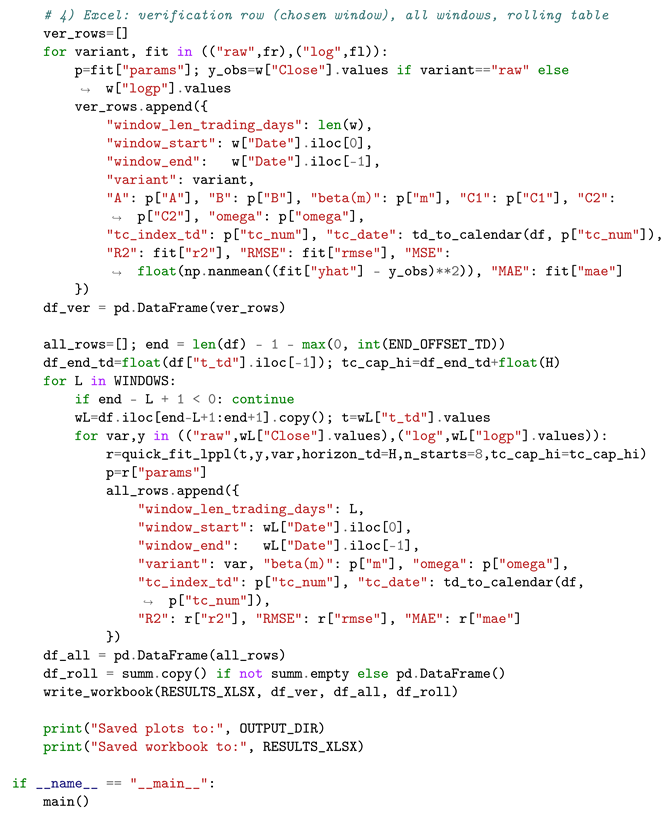

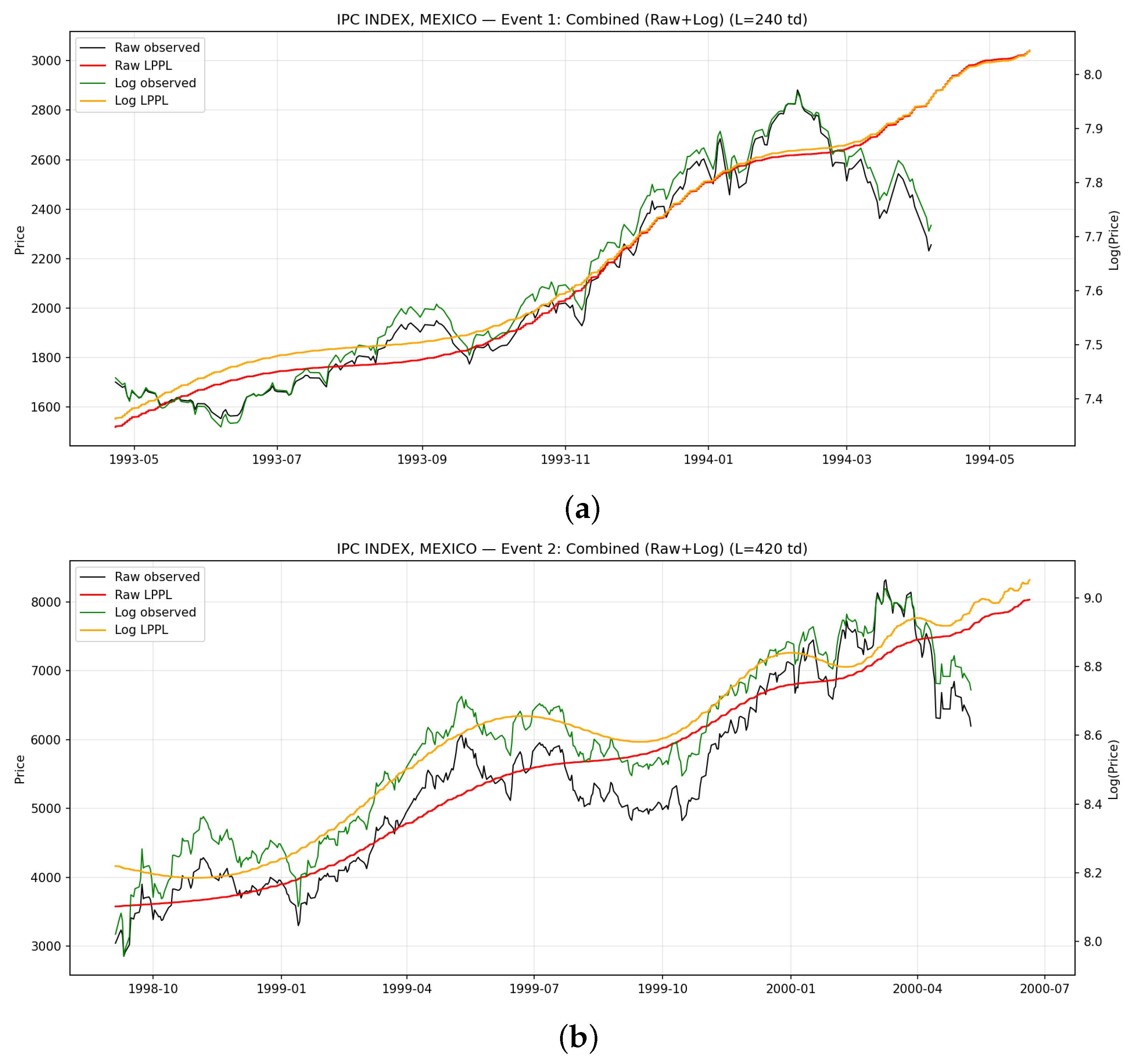

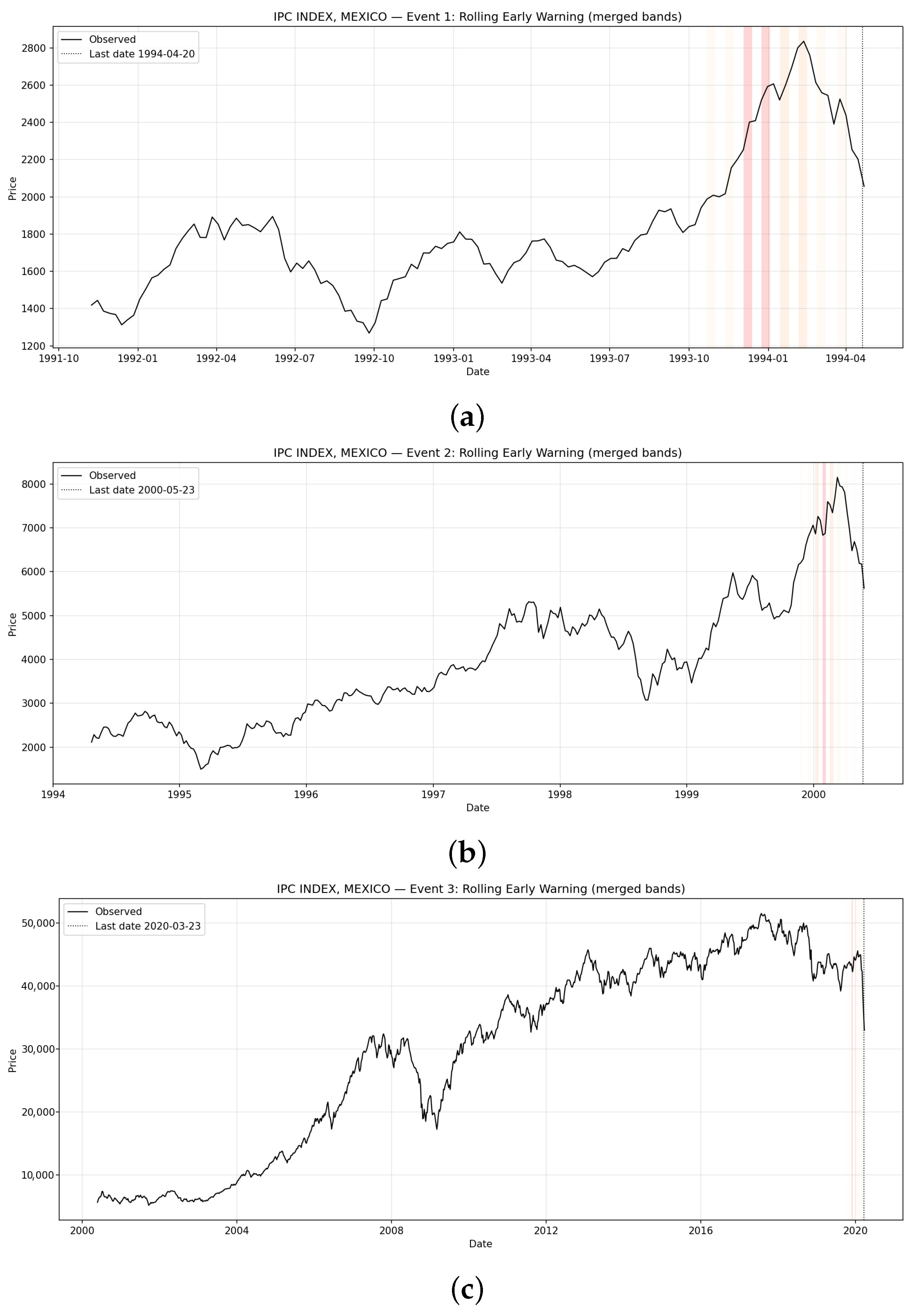

Figure 5.

Rolling early-warning signals for IPC/BMV Mexico across Events 1–3. Each panel visualizes merged LPPL warning bands (Very High, High, Elevated, Beyond 60) leading up to the observed crash date. (a) IPC Mexico—Event 1 (Rolling Early Warning); (b) IPC Mexico—Event 2 (Rolling Early Warning); (c) IPC Mexico—Event 3 (Rolling Early Warning).

Figure 5.

Rolling early-warning signals for IPC/BMV Mexico across Events 1–3. Each panel visualizes merged LPPL warning bands (Very High, High, Elevated, Beyond 60) leading up to the observed crash date. (a) IPC Mexico—Event 1 (Rolling Early Warning); (b) IPC Mexico—Event 2 (Rolling Early Warning); (c) IPC Mexico—Event 3 (Rolling Early Warning).

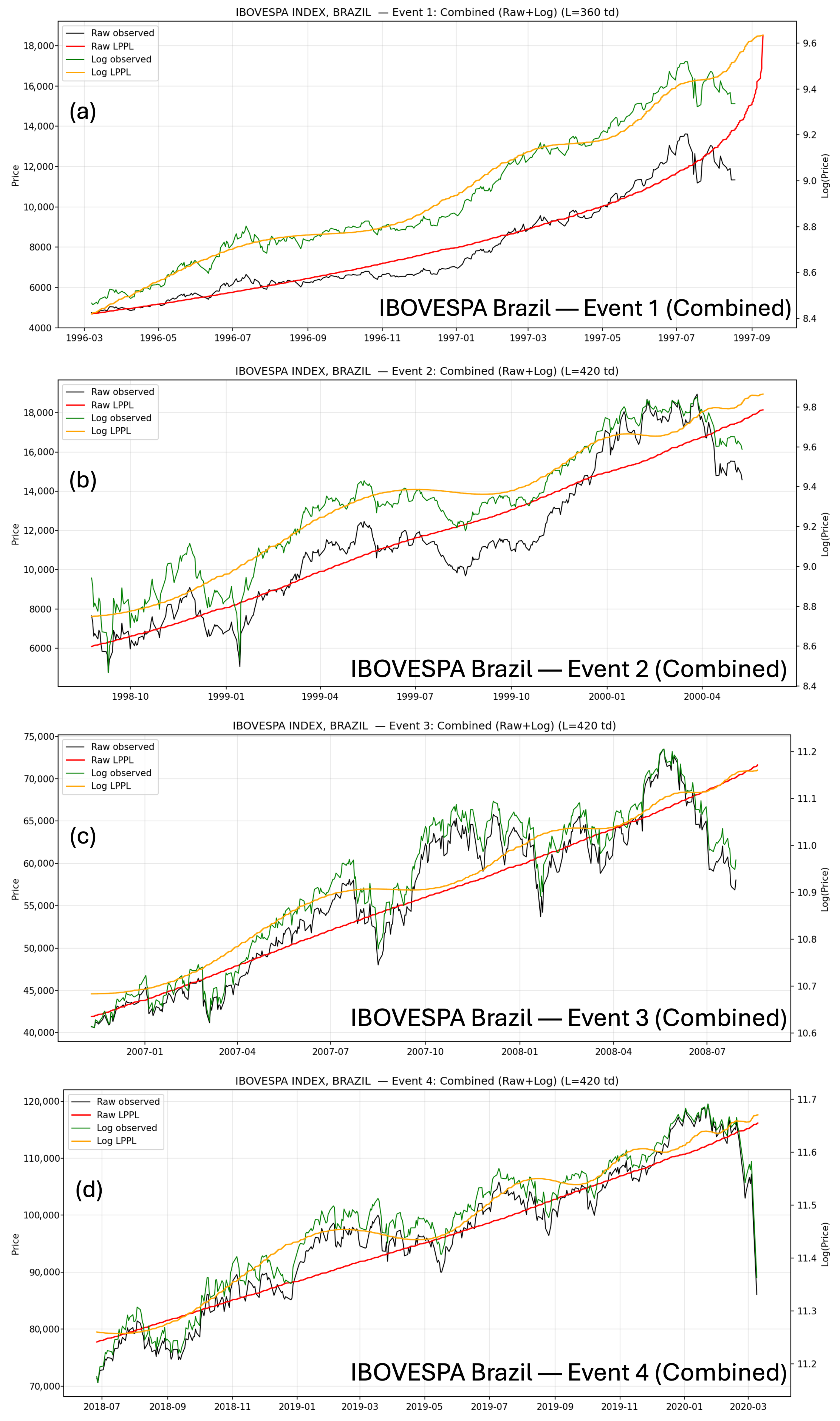

Figure 6.

Combined (Raw + Log) LPPL fits for IBOVESPA, Brazil across Events 1–4. Each panel overlays observed prices with the corresponding LPPL trajectories, highlighting the approach toward the estimated critical region before each historical crash.

Figure 6.

Combined (Raw + Log) LPPL fits for IBOVESPA, Brazil across Events 1–4. Each panel overlays observed prices with the corresponding LPPL trajectories, highlighting the approach toward the estimated critical region before each historical crash.

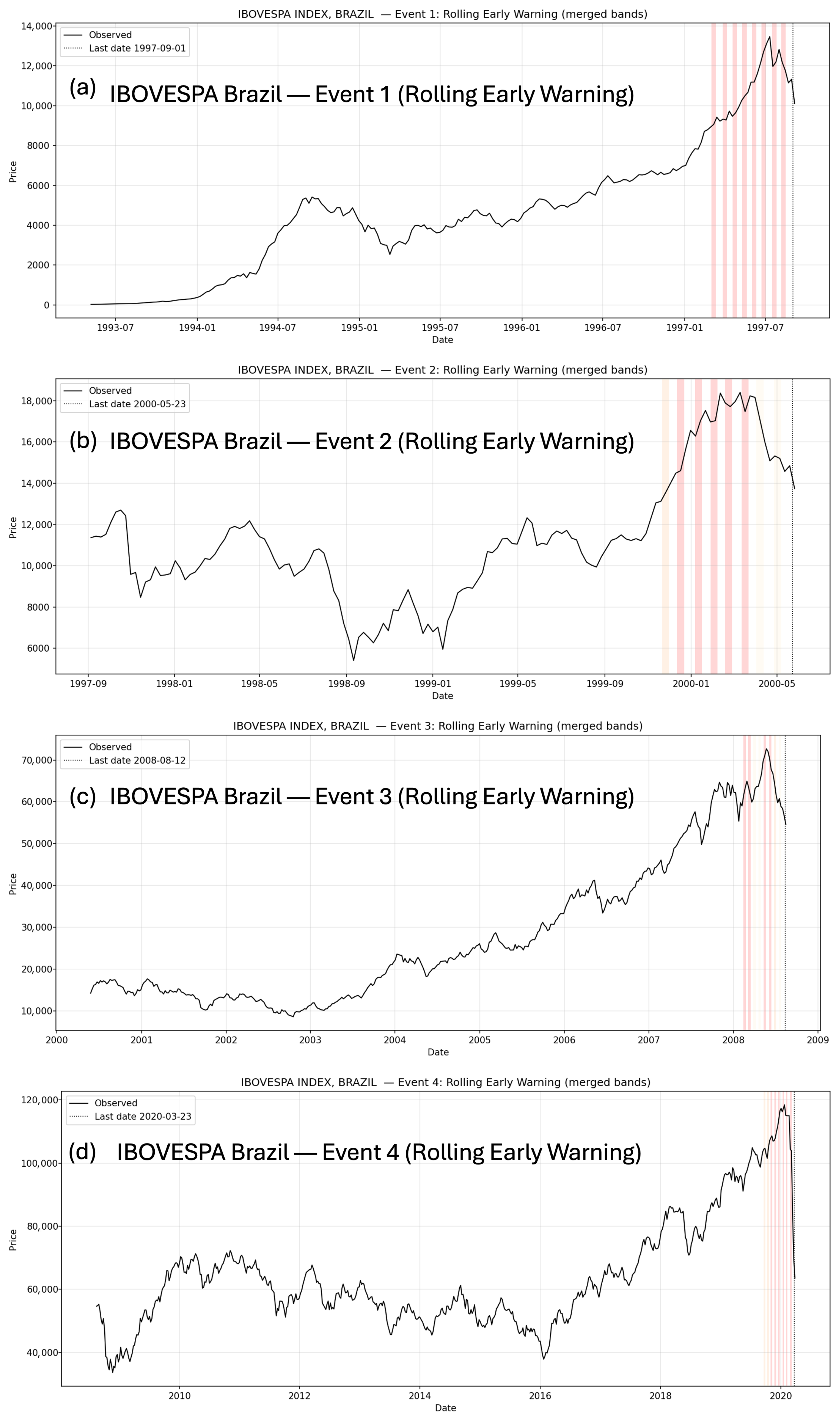

Figure 7.

Rolling early-warning signals for IBOVESPA, Brazil, across four major crash events. Each panel displays the observed price series together with merged LPPL-based early-warning bands, illustrating how risk signals intensify as each historical crash approaches.

Figure 7.

Rolling early-warning signals for IBOVESPA, Brazil, across four major crash events. Each panel displays the observed price series together with merged LPPL-based early-warning bands, illustrating how risk signals intensify as each historical crash approaches.

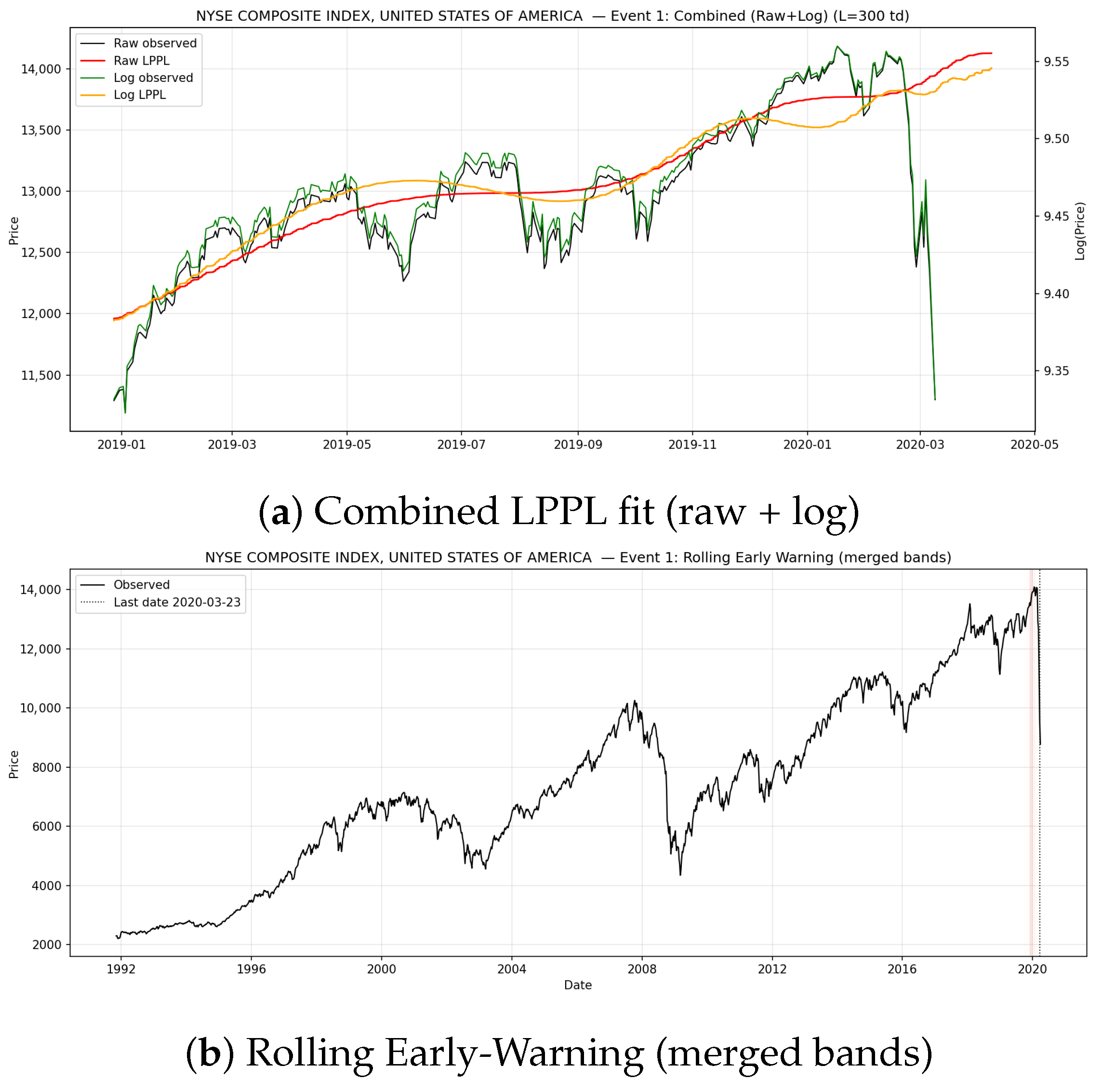

Figure 8.

NYSE Composite Index (USA)—Event 1. (a) Combined LPPL fit; (b) rolling early-warning bands showing the clustering of critical-time estimates ahead of the break.

Figure 8.

NYSE Composite Index (USA)—Event 1. (a) Combined LPPL fit; (b) rolling early-warning bands showing the clustering of critical-time estimates ahead of the break.

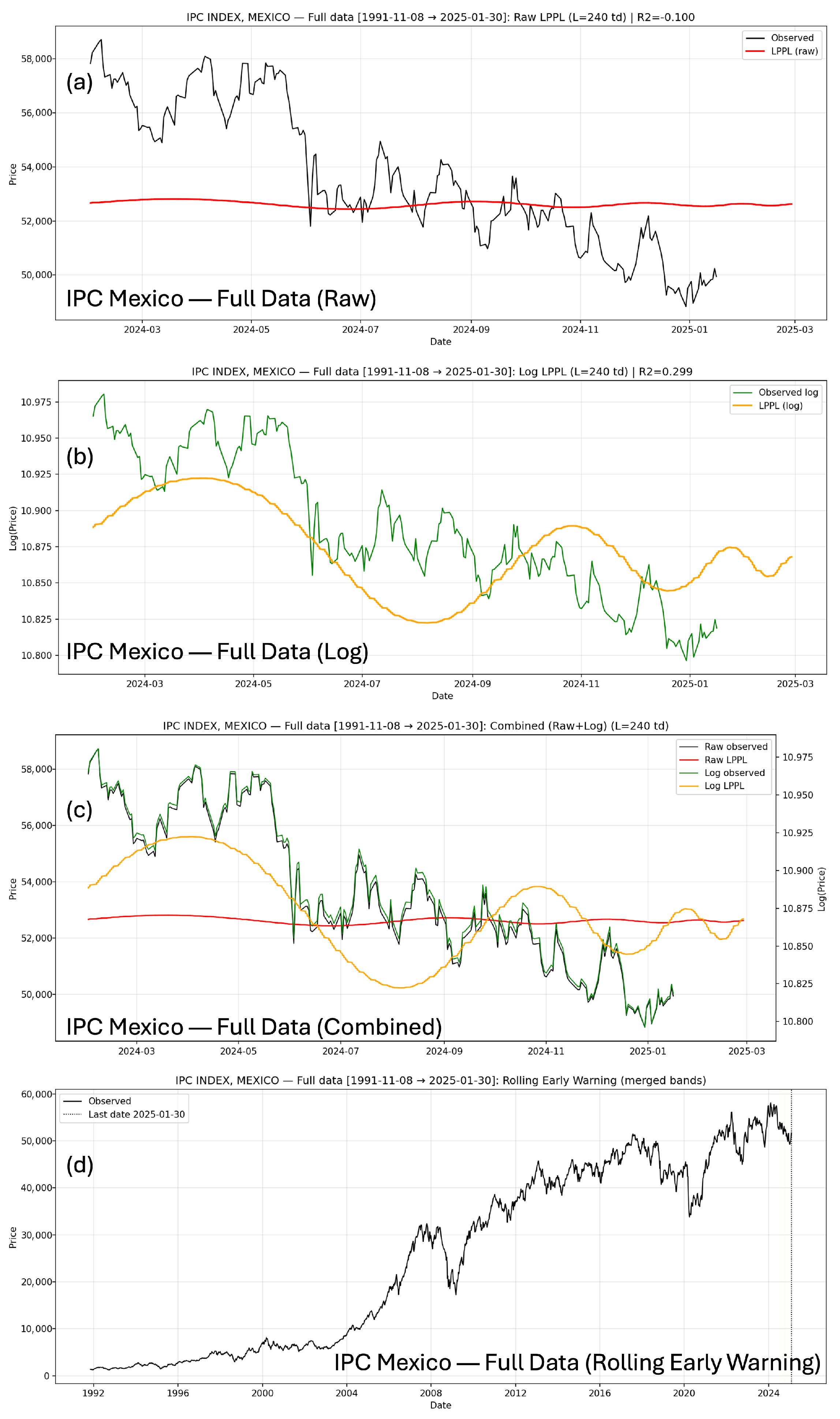

Figure 9.

LPPL analysis for IPC/BMV, Mexico using the full historical dataset. Panels show: (a) raw-price LPPL fit, (b) log-price LPPL fit, (c) combined overlay of raw and log variants, and (d) rolling early-warning intervals highlighting periods of increasing instability.

Figure 9.

LPPL analysis for IPC/BMV, Mexico using the full historical dataset. Panels show: (a) raw-price LPPL fit, (b) log-price LPPL fit, (c) combined overlay of raw and log variants, and (d) rolling early-warning intervals highlighting periods of increasing instability.

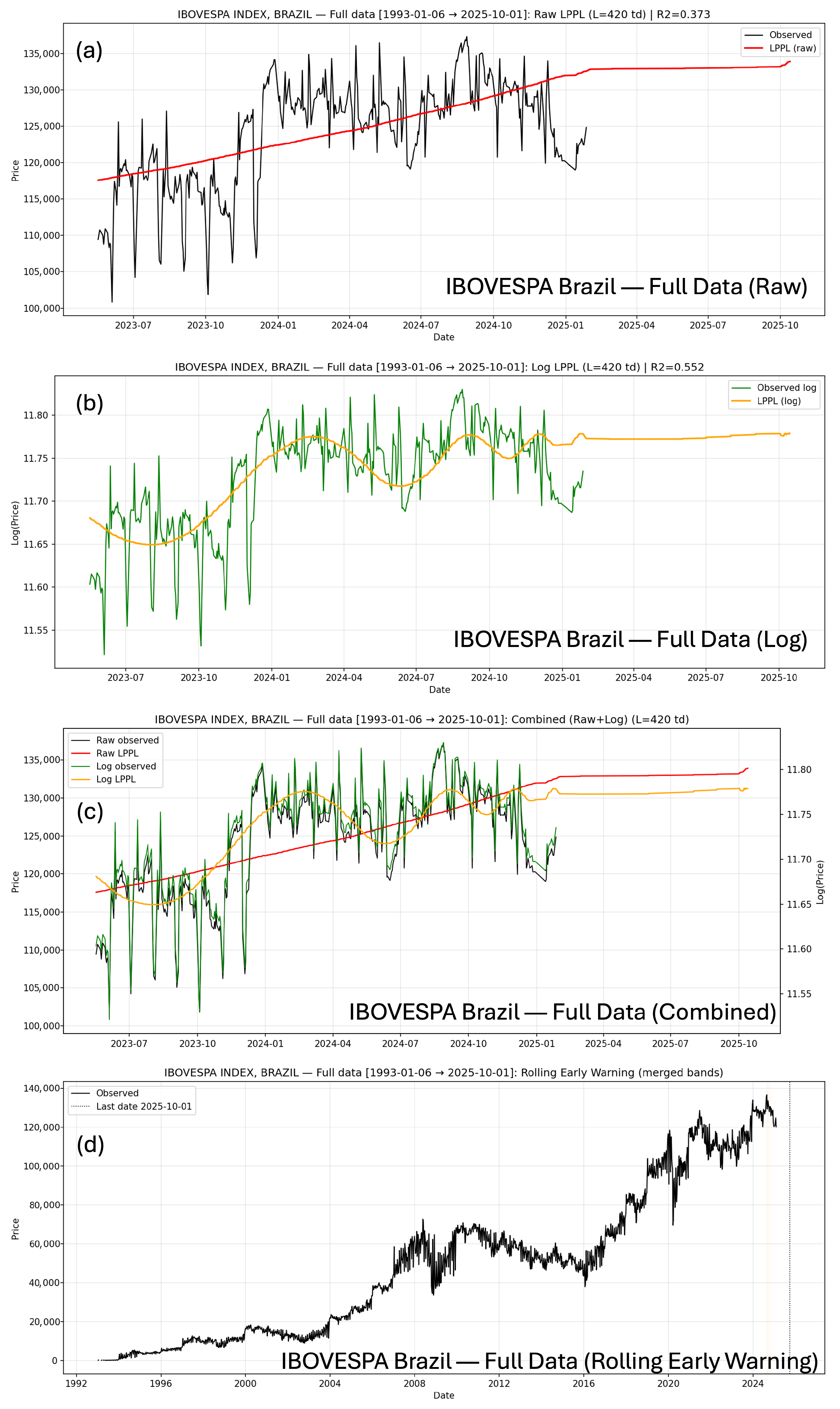

Figure 10.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil—LPPL analysis on the complete historical dataset. Panels show: (a) raw-price LPPL fit, (b) log-price LPPL fit, (c) combined LPPL view, and (d) rolling early-warning intervals highlighting instability prior to major downturns.

Figure 10.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil—LPPL analysis on the complete historical dataset. Panels show: (a) raw-price LPPL fit, (b) log-price LPPL fit, (c) combined LPPL view, and (d) rolling early-warning intervals highlighting instability prior to major downturns.

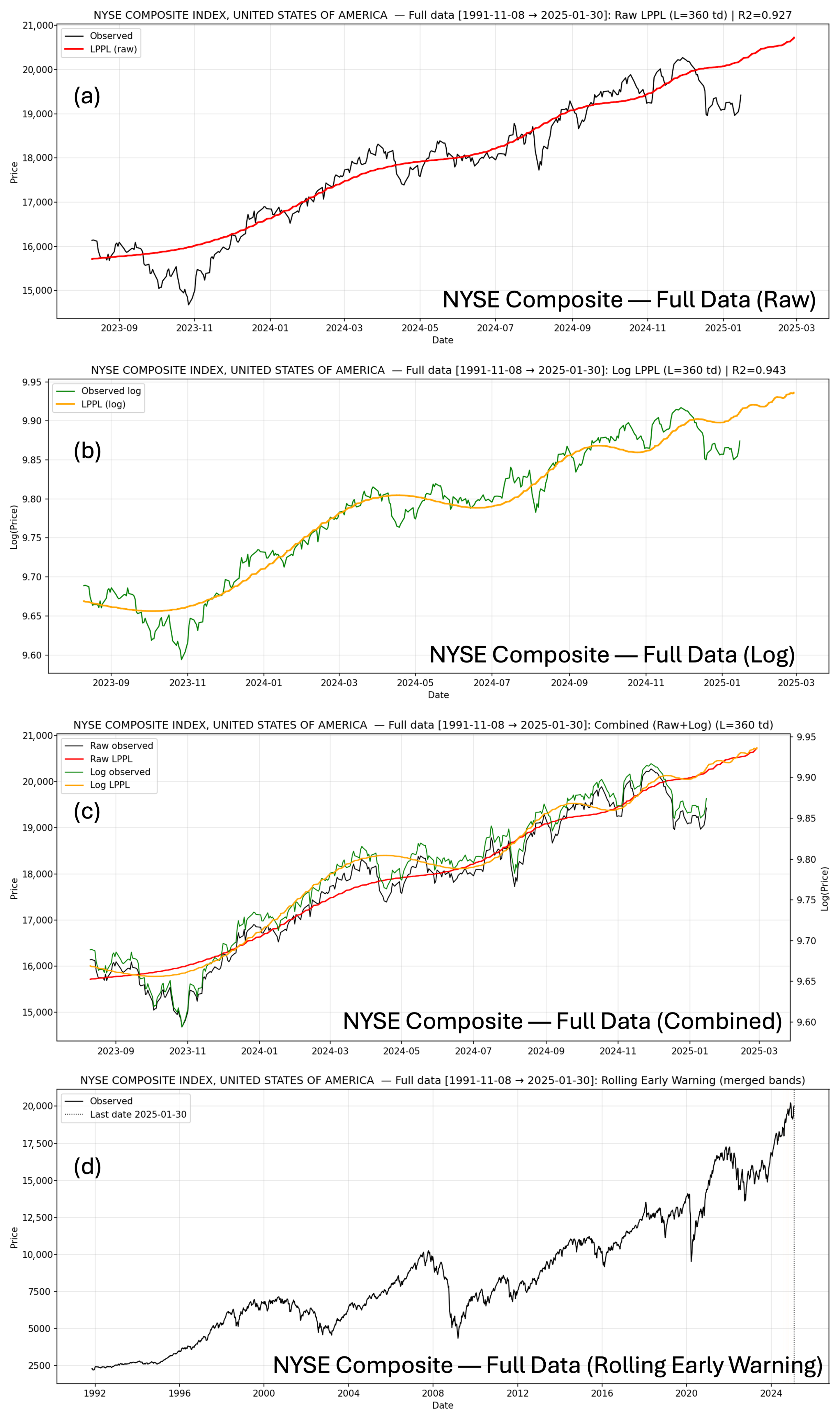

Figure 11.

NYSE Composite Index, United States—LPPL analysis on the complete historical dataset. Panels show: (a) raw-price LPPL fit, (b) log-price LPPL fit, (c) combined overlay, and (d) rolling early-warning intervals highlighting emerging instability before major downturns.

Figure 11.

NYSE Composite Index, United States—LPPL analysis on the complete historical dataset. Panels show: (a) raw-price LPPL fit, (b) log-price LPPL fit, (c) combined overlay, and (d) rolling early-warning intervals highlighting emerging instability before major downturns.

Table 1.

Parameters of the Log-Periodic Power-Law (LPPL) model.

Table 1.

Parameters of the Log-Periodic Power-Law (LPPL) model.

| Parameter | Description | Effect on Fit |

|---|

| A | Baseline log-price | Shifts the entire curve vertically. |

| B | Bubble acceleration term | Controls the overall curvature and acceleration of the growth. |

| C | Amplitude of the oscillations | Larger C produces stronger oscillatory behavior. |

| Critical time | Theoretical time of the bubble collapse. |

| Exponent controlling the curvature | Controls how steeply the curve bends near . |

| Frequency of log-periodic oscillations | Ensures oscillations occur near the critical point. |

| Phase shift of the oscillations | Influences the horizontal alignment of the bumps. |

Table 2.

Bound set for LPPL calibration on a trading-day time axis.

Table 2.

Bound set for LPPL calibration on a trading-day time axis.

| Parameter | Symbol | Meaning | Lower | Upper | Units/Notes |

|---|

| Exponent | | Curvature (faster-than-exponential growth) | | | dimensionless |

| Log-frequency | | Speed of log-periodic oscillations | 6 | 13 | dimensionless |

| Pre-crash slope | B | Strength/sign of acceleration | negative | | data-scaled; enforce |

| Critical time | | Regime-change time | | | trading days |

| Level (price fit) | A | Limiting price level | range-based | range-based | window-specific scaling |

| Level (log fit) | A | Limiting log-price | | | percentiles of |

Table 3.

LPPL parameter bounds used in estimation for raw-price and log-price fits.

Table 3.

LPPL parameter bounds used in estimation for raw-price and log-price fits.

| Parameter | Raw-Price Fit | Log-Price Fit |

|---|

| Level A | | |

| Pre-crash slope B | | |

| Curvature exponent | |

| Oscillation parameters | |

| Log-periodic frequency | |

| Critical time (trading-day axis) | , with trading days |

Table 4.

Historical crash events for IPC/BMV, IBOVESPA, and NYSE Composite indices based on peak and crash dates, showing percentage declines and window information.

Table 4.

Historical crash events for IPC/BMV, IBOVESPA, and NYSE Composite indices based on peak and crash dates, showing percentage declines and window information.

| Market | Event | Peak Date | Peak Close | +60 Days | −262 Days | Crash Date | Crash Close | Fall (%) |

|---|

| IPC (Mexico)

| 1 | 1994-02-04 | 2826.00 | 1994-05-04 | 1993-01-28 | 1994-04-20 | 1961.10 | 30.60 |

| IPC (Mexico)

| 2 | 2000-03-08 | 8295.20 | 2000-06-06 | 1999-03-03 | 2000-05-23 | 5593.58 | 32.56 |

| IPC (Mexico)

| 3 | 2020-01-20 | 45,902.68 | 2020-04-17 | 2019-01-04 | 2020-03-23 | 32,964.22 | 28.18 |

| IBOVESPA (Brazil)

| 1 | 1997-07-08 | 13,617.00 | 1997-09-30 | 1996-06-19 | 1997-09-01 | 10,109.00 | 23.22 |

| IBOVESPA (Brazil)

| 2 | 2000-03-27 | 18,951.00 | 2000-06-09 | 1999-03-09 | 2000-05-23 | 13,587.00 | 28.30 |

| IBOVESPA (Brazil)

| 3 | 2008-05-20 | 73,517.00 | 2008-08-13 | 2007-04-27 | 2008-08-12 | 54,503.00 | 25.86 |

| IBOVESPA (Brazil)

| 4 | 2020-01-23 | 11,9528.00 | 2020-04-23 | 2020-01-04 | 2020-03-23 | 63,570.00 | 46.81 |

| NYSE (USA)

| 1 | 2020-01-17 | 14,183.20 | 2020-04-14 | 2018-12-31 | 2020-03-23 | 8777.40 | 38.11 |

Table 5.

Baseline LPPL calibration for IPC/BMV (Events 1–3), showing selected window fits for raw and log specifications.

Table 5.

Baseline LPPL calibration for IPC/BMV (Events 1–3), showing selected window fits for raw and log specifications.

| Event | L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|

| Event 1

| 240 | 23/04/1993 | 06/04/1994 | raw | 0.8980 | 126.5832 | 87.5968 | 29/06/1994 |

| Event 1

| 240 | 23/04/1993 | 06/04/1994 | log | 0.9025 | 0.0584 | 0.0459 | 24/06/1994 |

| Event 2

| 420 | 04/09/1998 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.8710 | 473.2685 | 373.777 | 14/07/2000 |

| Event 2

| 420 | 04/09/1998 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.9140 | 0.0729 | 0.05726 | 23/06/2000 |

| Event 3

| 180 | 21/06/2019 | 06/03/2020 | raw | 0.3335 | 1254.9990 | 878.1074 | 14/04/2020 |

| Event 3

| 180 | 21/06/2019 | 06/03/2020 | log | 0.6357 | 0.0219 | 0.0173 | 09/04/2020 |

Table 6.

IPC Index, Mexico—Combined rolling-window early-warning summary for Events 1–3.

Table 6.

IPC Index, Mexico—Combined rolling-window early-warning summary for Events 1–3.

| Event | Window End | N Fits | Median | p25–p75 | Lead (TD) | Risk |

|---|

| 1 | 26/10/1993 | 2 | 01/01/1994 | 23/12/1993–10/01/1994 | 47.24 | Beyond60 |

| 1 | 17/11/1993 | 2 | 28/12/1993 | 18/12/1993–07/01/1994 | 29.32 | Elevated |

| 1 | 08/12/1993 | 2 | 11/12/1993 | 10/12/1993–12/12/1993 | 2.00 | Very High |

| 1 | 29/12/1993 | 2 | 01/01/1994 | 31/12/1993–02/01/1994 | 1.77 | Very High |

| 1 | 20/01/1994 | 2 | 02/02/1994 | 30/01/1994–05/02/1994 | 8.84 | High |

| 1 | 10/02/1994 | 2 | 24/02/1994 | 20/02/1994–28/02/1994 | 10.63 | High |

| 1 | 03/03/1994 | 2 | 09/04/1994 | 08/04/1994–10/04/1994 | 22.15 | Elevated |

| 1 | 28/03/1994 | 2 | 05/06/1994 | 28/05/1994–13/06/1994 | 48.35 | Beyond60 |

| 2 | 29/11/1999 | 3 | 08/02/2000 | 03/02/2000–14/02/2000 | 50.63 | Beyond60 |

| 2 | 20/12/1999 | 3 | 19/02/2000 | 09/02/2000–01/03/2000 | 43.75 | Beyond60 |

| 2 | 11/01/2000 | 4 | 20/02/2000 | 20/02/2000–20/02/2000 | 29.12 | Very High |

| 2 | 01/02/2000 | 3 | 18/03/2000 | 18/03/2000–18/03/2000 | 32.06 | High |

| 2 | 22/02/2000 | 2 | 26/02/2000 | 25/02/2000–27/02/2000 | 3.47 | Very High |

| 2 | 14/03/2000 | 2 | 19/04/2000 | 02/04/2000–05/05/2000 | 23.50 | Elevated |

| 2 | 05/04/2000 | 2 | 03/06/2000 | 02/06/2000–04/06/2000 | 37.82 | Beyond60 |

| 2 | 28/04/2000 | 2 | 27/06/2000 | 27/06/2000–27/06/2000 | 40.47 | Beyond60 |

| 3 | 27/09/2019 | 2 | 24/12/2019 | 24/12/2019–24/12/2019 | 59.98 | Beyond60 |

| 3 | 18/10/2019 | 2 | 16/01/2020 | 16/01/2020–16/01/2020 | 60.00 | Beyond60 |

| 3 | 08/11/2019 | 2 | 11/11/2019 | 11/11/2019–11/11/2019 | 1.00 | Very High |

| 3 | 02/12/2019 | 2 | 25/02/2020 | 25/02/2020–25/02/2020 | 57.29 | Beyond60 |

| 3 | 24/12/2019 | 2 | 04/01/2020 | 30/12/2019–09/01/2020 | 6.85 | Very High |

| 3 | 16/01/2020 | 2 | 13/02/2020 | 30/01/2020–27/02/2020 | 20.08 | Elevated |

| 3 | 07/02/2020 | 2 | 12/03/2020 | 01/03/2020–23/03/2020 | 23.47 | Elevated |

| 3 | 28/02/2020 | 2 | 01/04/2020 | 27/03/2020–05/04/2020 | 21.95 | Elevated |

Table 7.

IPC Index, Mexico (Events 1–3): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants (all L included).

Table 7.

IPC Index, Mexico (Events 1–3): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants (all L included).

| Event | L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | | | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|

| 1 | 180 | 19/07/1993 | 06/04/1994 | raw | 0.900 | 10.944 | 0.793 | 159.323 | 108.737 | 10/05/1994 |

| 1 | 180 | 19/07/1993 | 06/04/1994 | log | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.871 | 0.056 | 0.043 | 24/06/1994 |

| 1 | 240 | 23/04/1993 | 06/04/1994 | raw | 0.900 | 7.091 | 0.898 | 126.583 | 87.597 | 29/06/1994 |

| 1 | 240 | 23/04/1993 | 06/04/1994 | log | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.903 | 0.058 | 0.046 | 24/06/1994 |

| 1 | 300 | 25/01/1993 | 06/04/1994 | raw | 0.874 | 11.246 | 0.842 | 155.458 | 111.892 | 09/05/1994 |

| 1 | 300 | 25/01/1993 | 06/04/1994 | log | 0.900 | 10.281 | 0.873 | 0.067 | 0.051 | 19/04/1994 |

| 1 | 360 | 23/10/1992 | 06/04/1994 | raw | 0.252 | 12.000 | 0.788 | 172.920 | 141.555 | 10/05/1994 |

| 1 | 360 | 23/10/1992 | 06/04/1994 | log | 0.756 | 9.089 | 0.825 | 0.075 | 0.063 | 25/04/1994 |

| 1 | 420 | 28/07/1992 | 06/04/1994 | raw | 0.261 | 10.452 | 0.823 | 165.987 | 134.460 | 04/05/1994 |

| 1 | 420 | 28/07/1992 | 06/04/1994 | log | 0.248 | 12.000 | 0.855 | 0.075 | 0.063 | 15/06/1994 |

| 2 | 180 | 19/08/1999 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.900 | 8.913 | 0.681 | 575.521 | 382.868 | 23/06/2000 |

| 2 | 180 | 19/08/1999 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.900 | 11.121 | 0.797 | 0.073 | 0.057 | 27/07/2000 |

| 2 | 240 | 27/05/1999 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.900 | 10.492 | 0.703 | 535.718 | 443.086 | 19/07/2000 |

| 2 | 240 | 27/05/1999 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.900 | 10.888 | 0.823 | 0.066 | 0.050 | 27/07/2000 |

| 2 | 300 | 01/03/1999 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.900 | 7.453 | 0.715 | 532.832 | 426.807 | 12/06/2000 |

| 2 | 300 | 01/03/1999 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.851 | 0.063 | 0.046 | 23/05/2000 |

| 2 | 360 | 02/12/1998 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.900 | 9.881 | 0.836 | 492.630 | 388.205 | 19/07/2000 |

| 2 | 360 | 02/12/1998 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.899 | 8.642 | 0.913 | 0.065 | 0.052 | 28/06/2000 |

| 2 | 420 | 04/09/1998 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.900 | 9.645 | 0.871 | 473.269 | 373.777 | 14/07/2000 |

| 2 | 420 | 04/09/1998 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.794 | 8.353 | 0.914 | 0.073 | 0.057 | 23/06/2000 |

| 3 | 180 | 21/06/2019 | 06/03/2020 | raw | 0.900 | 10.963 | 0.334 | 1254.999 | 878.107 | 14/04/2020 |

| 3 | 180 | 21/06/2019 | 06/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 10.516 | 0.636 | 0.022 | 0.017 | 09/04/2020 |

| 3 | 240 | 26/03/2019 | 06/03/2020 | raw | 0.900 | 10.204 | 0.078 | 1375.203 | 988.478 | 15/04/2020 |

| 3 | 240 | 26/03/2019 | 06/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 7.854 | 0.561 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 18/03/2020 |

| 3 | 300 | 27/12/2018 | 06/03/2020 | raw | 0.877 | 8.563 | 0.070 | 1285.012 | 938.789 | 01/05/2020 |

| 3 | 300 | 27/12/2018 | 06/03/2020 | log | 0.591 | 7.000 | 0.357 | 0.025 | 0.020 | 12/03/2020 |

| 3 | 360 | 28/09/2018 | 06/03/2020 | raw | 0.118 | 9.898 | −0.052 | 1829.909 | 1247.919 | 23/03/2020 |

| 3 | 360 | 28/09/2018 | 06/03/2020 | log | 0.899 | 11.134 | 0.277 | 0.035 | 0.028 | 23/04/2020 |

| 3 | 420 | 06/07/2018 | 06/03/2020 | raw | 0.100 | 8.511 | −0.069 | 2741.002 | 1915.435 | 18/03/2020 |

| 3 | 420 | 06/07/2018 | 06/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 10.111 | 0.581 | 0.038 | 0.032 | 09/04/2020 |

Table 8.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil—LPPL All-Window Results Across Events 1–4.

Table 8.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil—LPPL All-Window Results Across Events 1–4.

| Event | L (TD) | Start | End | Variant | | | | RMSE | |

|---|

| 1 | 180 | 22/11/1996 | 18/08/1997 | raw | 0.900 | 11.263 | 0.934 | 520.928 | 02/09/1997 |

| 1 | 180 | 22/11/1996 | 18/08/1997 | log | 0.900 | 10.247 | 0.956 | 0.044 | 05/11/1997 |

| 1 | 240 | 28/08/1996 | 18/08/1997 | raw | 0.900 | 11.450 | 0.937 | 563.265 | 09/10/1997 |

| 1 | 240 | 28/08/1996 | 18/08/1997 | log | 0.900 | 10.524 | 0.975 | 0.039 | 05/11/1997 |

| 1 | 300 | 04/06/1996 | 18/08/1997 | raw | 0.537 | 7.363 | 0.926 | 628.025 | 26/08/1997 |

| 1 | 300 | 04/06/1996 | 18/08/1997 | log | 0.900 | 7.277 | 0.972 | 0.044 | 03/09/1997 |

| 1 | 360 | 07/03/1996 | 18/08/1997 | raw | 0.341 | 7.206 | 0.944 | 576.249 | 10/09/1997 |

| 1 | 360 | 07/03/1996 | 18/08/1997 | log | 0.536 | 9.530 | 0.978 | 0.044 | 05/11/1997 |

| 1 | 420 | 05/12/1995 | 18/08/1997 | raw | 0.312 | 11.017 | 0.947 | 572.033 | 01/09/1997 |

| 1 | 420 | 05/12/1995 | 18/08/1997 | log | 0.383 | 9.695 | 0.971 | 0.054 | 05/11/1997 |

| 2 | 180 | 17/08/1999 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.900 | 7.325 | 0.695 | 1520.923 | 28/07/2000 |

| 2 | 180 | 17/08/1999 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.780 | 0.091 | 07/06/2000 |

| 2 | 240 | 21/05/1999 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.900 | 7.622 | 0.742 | 1453.102 | 24/05/2000 |

| 2 | 240 | 21/05/1999 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.837 | 0.083 | 13/06/2000 |

| 2 | 300 | 23/02/1999 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.900 | 7.224 | 0.742 | 1447.654 | 01/08/2000 |

| 2 | 300 | 23/02/1999 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.863 | 0.077 | 13/06/2000 |

| 2 | 360 | 20/11/1998 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.900 | 8.081 | 0.820 | 1411.947 | 12/05/2000 |

| 2 | 360 | 20/11/1998 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.884 | 0.094 | 13/06/2000 |

| 2 | 420 | 25/08/1998 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.895 | 7.863 | 0.867 | 1321.127 | 29/05/2000 |

| 2 | 420 | 25/08/1998 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.857 | 7.178 | 0.907 | 0.098 | 13/06/2000 |

| 3 | 180 | 31/10/2007 | 29/07/2008 | raw | 0.892 | 8.196 | 0.088 | 3784.436 | 21/10/2008 |

| 3 | 180 | 31/10/2007 | 29/07/2008 | log | 0.100 | 7.000 | 0.486 | 0.044 | 16/10/2008 |

| 3 | 240 | 06/08/2007 | 29/07/2008 | raw | 0.897 | 7.094 | 0.333 | 4133.321 | 03/09/2008 |

| 3 | 240 | 06/08/2007 | 29/07/2008 | log | 0.194 | 8.136 | 0.568 | 0.055 | 16/10/2008 |

| 3 | 300 | 10/05/2007 | 29/07/2008 | raw | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.552 | 3760.540 | 22/09/2008 |

| 3 | 300 | 10/05/2007 | 29/07/2008 | log | 0.160 | 8.052 | 0.687 | 0.052 | 16/10/2008 |

| 3 | 360 | 12/02/2007 | 29/07/2008 | raw | 0.900 | 10.028 | 0.719 | 3928.244 | 30/07/2008 |

| 3 | 360 | 12/02/2007 | 29/07/2008 | log | 0.900 | 7.080 | 0.813 | 0.057 | 16/10/2008 |

| 3 | 420 | 10/11/2006 | 29/07/2008 | raw | 0.900 | 7.449 | 0.814 | 3724.216 | 19/08/2008 |

| 3 | 420 | 10/11/2006 | 29/07/2008 | log | 0.900 | 10.721 | 0.829 | 0.066 | 16/10/2008 |

| 4 | 180 | 18/06/2019 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.887 | 9.171 | 0.488 | 4372.670 | 10/03/2020 |

| 4 | 180 | 18/06/2019 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.100 | 7.000 | 0.546 | 0.0383 | 27/05/2020 |

| 4 | 240 | 22/03/2019 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.874 | 7.287 | 0.707 | 4032.579 | 10/03/2020 |

| 4 | 240 | 22/03/2019 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 11.738 | 0.743 | 0.0362 | 30/03/2020 |

| 4 | 300 | 19/12/2018 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.810 | 9.842 | 0.741 | 3960.696 | 10/03/2020 |

| 4 | 300 | 19/12/2018 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 11.739 | 0.789 | 0.0346 | 30/03/2020 |

| 4 | 360 | 20/09/2018 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.852 | 10.832 | 0.842 | 3820.879 | 10/03/2020 |

| 4 | 360 | 20/09/2018 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 11.655 | 0.869 | 0.0352 | 07/05/2020 |

| 4 | 420 | 26/06/2018 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.875 | 7.765 | 0.884 | 4070.039 | 10/03/2020 |

| 4 | 420 | 26/06/2018 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 11.000 | 0.915 | 0.0317 | 04/05/2020 |

Table 9.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil—Baseline LPPL calibrations across Events 1–4 (selected windows).

Table 9.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil—Baseline LPPL calibrations across Events 1–4 (selected windows).

| Event | L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | RMSE | MSE | MAE | |

|---|

| 1 | 360 | 07/03/1996 | 18/08/1997 | raw | 0.944 | 576.249 | 3.321 × | 403.835 | 10/09/1997 |

| 1 | 360 | 07/03/1996 | 18/08/1997 | log | 0.978 | 0.044 | 1.913 × | 0.034 | 05/11/1997 |

| 2 | 420 | 25/08/1998 | 09/05/2000 | raw | 0.867 | 1321.127 | 1.745 × | 1076.291 | 29/05/2000 |

| 2 | 420 | 25/08/1998 | 09/05/2000 | log | 0.907 | 0.098 | 9.646 × | 0.076 | 13/06/2000 |

| 3 | 420 | 10/11/2006 | 29/07/2008 | raw | 0.814 | 3724.216 | 1.386 × | 2757.621 | 19/08/2008 |

| 3 | 420 | 10/11/2006 | 29/07/2008 | log | 0.829 | 0.0657 | 4.310 × | 0.049 | 16/10/2008 |

| 4 | 420 | 26/06/2018 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.884 | 4070.039 | 1.657 × | 2983.762 | 10/03/2020 |

| 4 | 420 | 26/06/2018 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.917 | 0.03666 | 1.344 × | 0.02669 | 31/03/2020 |

Table 10.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil—Rolling-window early-warning summary across Events 1–4.

Table 10.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil—Rolling-window early-warning summary across Events 1–4.

| Event | Window End | Median | p25 | p75 | Lead (TD) | Risk |

|---|

| E1 | 07/03/1997 | 11/03/1997 | 11/03/1997 | 11/03/1997 | 2.16 | Very High |

| E1 | 01/04/1997 | 09/04/1997 | 08/04/1997 | 09/04/1997 | 6.10 | Very High |

| E1 | 23/04/1997 | 11/05/1997 | 10/05/1997 | 12/05/1997 | 11.76 | High |

| E1 | 15/05/1997 | 22/05/1997 | 22/05/1997 | 22/05/1997 | 5.43 | Very High |

| E1 | 06/06/1997 | 11/06/1997 | 11/06/1997 | 11/06/1997 | 3.14 | Very High |

| E1 | 27/06/1997 | 02/07/1997 | 01/07/1997 | 03/07/1997 | 2.85 | Very High |

| E1 | 21/07/1997 | 23/07/1997 | 22/07/1997 | 23/07/1997 | 1.97 | Very High |

| E1 | 11/08/1997 | 14/08/1997 | 14/08/1997 | 14/08/1997 | 3.35 | Very High |

| E2 | 26/11/1999 | 22/12/1999 | 16/12/1999 | 29/12/1999 | 17.90 | Elevated |

| E2 | 17/12/1999 | 28/12/1999 | 24/12/1999 | 01/01/2000 | 6.53 | Very High |

| E2 | 11/01/2000 | 12/01/2000 | 12/01/2000 | 12/01/2000 | 1.00 | Very High |

| E2 | 02/02/2000 | 03/02/2000 | 03/02/2000 | 03/02/2000 | 1.42 | Very High |

| E2 | 23/02/2000 | 26/02/2000 | 25/02/2000 | 27/02/2000 | 2.70 | Very High |

| E2 | 17/03/2000 | 21/03/2000 | 21/03/2000 | 21/03/2000 | 2.76 | Very High |

| E2 | 07/04/2000 | 06/05/2000 | 23/04/2000 | 19/05/2000 | 19.14 | Elevated |

| E2 | 02/05/2000 | 11/06/2000 | 27/05/2000 | 26/06/2000 | 28.82 | Elevated |

| E3 | 19/02/2008 | 24/02/2008 | 22/02/2008 | 26/02/2008 | 4.58 | Very High |

| E3 | 11/03/2008 | 16/03/2008 | 14/03/2008 | 18/03/2008 | 4.16 | Very High |

| E3 | 02/04/2008 | 02/05/2008 | 23/04/2008 | 10/05/2008 | 19.77 | Elevated |

| E3 | 24/04/2008 | 10/06/2008 | 09/06/2008 | 11/07/2008 | 31.13 | Beyond60 |

| E3 | 16/05/2008 | 19/05/2008 | 19/05/2008 | 19/05/2008 | 1.12 | Very High |

| E3 | 09/06/2008 | 10/06/2008 | 10/06/2008 | 10/06/2008 | 1.60 | Very High |

| E3 | 30/06/2008 | 14/08/2008 | 12/08/2008 | 16/08/2008 | 32.28 | High |

| E3 | 22/07/2008 | 16/09/2008 | 15/09/2008 | 17/09/2008 | 41.00 | Elevated |

| E4 | 25/09/2019 | 07/10/2019 | 01/10/2019 | 12/10/2019 | 8.78 | High |

| E4 | 16/10/2019 | 01/11/2019 | 30/10/2019 | 03/11/2019 | 11.76 | High |

| E4 | 06/11/2019 | 07/11/2019 | 07/11/2019 | 07/11/2019 | 1.05 | Very High |

| E4 | 29/11/2019 | 03/12/2019 | 03/12/2019 | 03/12/2019 | 2.46 | Very High |

| E4 | 20/12/2019 | 25/12/2019 | 24/12/2019 | 26/12/2019 | 2.03 | Very High |

| E4 | 16/01/2020 | 22/01/2020 | 21/01/2020 | 22/01/2020 | 3.81 | Very High |

| E4 | 06/02/2020 | 10/02/2020 | 10/02/2020 | 10/02/2020 | 2.07 | Very High |

| E4 | 02/03/2020 | 05/03/2020 | 05/03/2020 | 05/03/2020 | 3.10 | Very High |

Table 11.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Event 1): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants.

Table 11.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Event 1): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants.

| L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | | | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|

| 180 | 21/06/2019 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.900 | 7.914 | 0.283 | 429.399 | 242.125 | 01/06/2020 |

| 180 | 21/06/2019 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.370 | 0.030 | 0.020 | 07/04/2020 |

| 240 | 27/03/2019 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.900 | 7.833 | 0.395 | 386.771 | 250.308 | 01/06/2020 |

| 240 | 27/03/2019 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.100 | 7.000 | 0.456 | 0.028 | 0.019 | 27/05/2020 |

| 300 | 28/12/2018 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.900 | 7.000 | 0.631 | 360.816 | 239.632 | 25/05/2020 |

| 300 | 28/12/2018 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 7.001 | 0.652 | 0.027 | 0.019 | 08/04/2020 |

| 360 | 02/10/2018 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.883 | 8.073 | 0.615 | 400.201 | 286.114 | 22/04/2020 |

| 360 | 02/10/2018 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 8.765 | 0.633 | 0.031 | 0.023 | 27/04/2020 |

| 420 | 09/07/2018 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.900 | 9.565 | 0.515 | 418.248 | 305.498 | 01/06/2020 |

| 420 | 09/07/2018 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.900 | 8.472 | 0.593 | 0.030 | 0.023 | 19/03/2020 |

Table 12.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Event 1): Baseline calibration (selected window).

Table 12.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Event 1): Baseline calibration (selected window).

| L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | RMSE | |

|---|

| 300 | 28/12/2018 | 09/03/2020 | raw | 0.6520 | 350.2434 | 01/06/2020 |

| 300 | 28/12/2018 | 09/03/2020 | log | 0.6516 | 0.0271 | 08/04/2020 |

Table 13.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Event 1): Rolling-window early-warning summary.

Table 13.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Event 1): Rolling-window early-warning summary.

| Window End | N Fits | Median | p25 | p75 | Lead (TD) | Risk |

|---|

| 30/09/2019 | 2 | 06/12/2019 12:00 | 04/12/2019 06:00 | 08/12/2019 18:00 | 47.54 | Beyond60 |

| 21/10/2019 | 2 | 05/12/2019 12:00 | 05/12/2019 06:00 | 05/12/2019 18:00 | 32.37 | Beyond60 |

| 11/11/2019 | 2 | 18/12/2019 12:00 | 17/12/2019 18:00 | 19/12/2019 06:00 | 26.06 | Elevated |

| 03/12/2019 | 2 | 04/12/2019 12:00 | 04/12/2019 06:00 | 04/12/2019 18:00 | 1.57 | Very High |

| 24/12/2019 | 2 | 26/12/2019 12:00 | 26/12/2019 06:00 | 26/12/2019 18:00 | 1.91 | Very High |

| 16/01/2020 | 2 | 29/01/2020 00:00 | 28/01/2020 12:00 | 29/01/2020 12:00 | 7.97 | High |

| 07/02/2020 | 2 | 29/02/2020 12:00 | 28/02/2020 06:00 | 01/03/2020 18:00 | 14.76 | Elevated |

| 02/03/2020 | 2 | 04/05/2020 12:00 | 24/04/2020 06:00 | 14/05/2020 18:00 | 45.36 | Beyond60 |

Table 14.

IPC Index, Mexico (Complete Data): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants.

Table 14.

IPC Index, Mexico (Complete Data): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants.

| L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | | | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|

| 180 | 01/05/2024 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.900 | 11.141 | 0.018 | 4378.201 | 3459.006 | 05/12/2025 |

| 180 | 01/05/2024 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.100 | 11.439 | 0.198 | 0.031 | 0.026 | 05/12/2025 |

| 240 | 04/02/2024 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.900 | 9.319 | 0.017 | 4061.632 | 3156.952 | 25/11/2025 |

| 240 | 04/02/2024 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.100 | 7.993 | 0.148 | 0.030 | 0.024 | 27/10/2025 |

| 300 | 04/11/2023 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.598 | 10.185 | 0.009 | 4831.839 | 3446.462 | 09/12/2025 |

| 300 | 04/11/2023 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.832 | 9.904 | 0.190 | 0.035 | 0.027 | 19/11/2025 |

| 360 | 11/08/2023 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.890 | 7.846 | 0.253 | 5758.913 | 4497.731 | 21/10/2025 |

| 360 | 11/08/2023 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.900 | 9.234 | 0.542 | 0.037 | 0.029 | 11/11/2025 |

| 420 | 17/05/2023 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.782 | 10.327 | 0.373 | 5855.791 | 4587.339 | 13/10/2025 |

| 420 | 17/05/2023 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.900 | 7.994 | 0.550 | 0.041 | 0.031 | 24/10/2025 |

Table 15.

IPC Index, Mexico (Complete Data): Baseline calibration (selected window).

Table 15.

IPC Index, Mexico (Complete Data): Baseline calibration (selected window).

| L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | RMSE | MSE | MAE | |

|---|

| 240 | 01/02/2024 | 16/01/2025 | raw | −0.1000 | 2700.6270 | 7,293,384.0000 | 2146.4970 | 02/04/2025 |

| 240 | 01/02/2024 | 16/01/2025 | log | 0.2994 | 0.0401 | 0.0016 | 0.0344 | 24/03/2025 |

Table 16.

IPC Index, Mexico (Complete Data): Rolling-window early-warning summary.

Table 16.

IPC Index, Mexico (Complete Data): Rolling-window early-warning summary.

| Window End | N Fits | Median | p25 | p75 | Lead (TD) | Risk |

|---|

| 07/08/2024 | 2 | 01/11/2024 | 01/11/2024 | 01/11/2024 | 60.0000 | Beyond60 |

| 28/08/2024 | 2 | 11/11/2024 | 04/11/2024 | 18/11/2024 | 50.3838 | Beyond60 |

| 19/09/2024 | 2 | 14/12/2024 | 12/12/2024 | 15/12/2024 | 58.7288 | Beyond60 |

| 11/10/2024 | 2 | 21/12/2024 | 20/12/2024 | 22/12/2024 | 48.5660 | Beyond60 |

| 01/11/2024 | 2 | 24/01/2025 | 22/01/2025 | 26/01/2025 | 54.7069 | Beyond60 |

| 25/11/2024 | 2 | 18/02/2025 | 18/02/2025 | 18/02/2025 | 58.6106 | Beyond60 |

| 17/12/2024 | 2 | 13/03/2025 | 13/03/2025 | 13/03/2025 | 59.9475 | Beyond60 |

| 09/01/2025 | 2 | 30/03/2025 | 28/03/2025 | 01/04/2025 | 56.7975 | Beyond60 |

Table 17.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil (Complete Data): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants.

Table 17.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil (Complete Data): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants.

| L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | | | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|

| 180 | 01/05/2024 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.900 | 11.141 | 0.018 | 4378.201 | 3459.006 | 05/12/2025 |

| 180 | 01/05/2024 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.100 | 11.439 | 0.198 | 0.031 | 0.026 | 05/12/2025 |

| 240 | 04/02/2024 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.900 | 9.319 | 0.017 | 4061.632 | 3156.952 | 25/11/2025 |

| 240 | 04/02/2024 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.100 | 7.993 | 0.148 | 0.030 | 0.024 | 27/10/2025 |

| 300 | 04/11/2023 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.598 | 10.185 | 0.009 | 4831.839 | 3446.462 | 09/12/2025 |

| 300 | 04/11/2023 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.832 | 9.904 | 0.190 | 0.035 | 0.027 | 19/11/2025 |

| 360 | 11/08/2023 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.890 | 7.846 | 0.253 | 5758.913 | 4497.731 | 21/10/2025 |

| 360 | 11/08/2023 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.900 | 9.234 | 0.542 | 0.037 | 0.029 | 11/11/2025 |

| 420 | 17/05/2023 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.782 | 10.327 | 0.373 | 5855.791 | 4587.339 | 13/10/2025 |

| 420 | 17/05/2023 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.900 | 7.994 | 0.550 | 0.041 | 0.031 | 24/10/2025 |

Table 18.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil (Event 4): Baseline calibration (selected window).

Table 18.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil (Event 4): Baseline calibration (selected window).

| L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | RMSE | MSE | MAE | |

|---|

| 420 | 17/05/2023 | 27/01/2025 | raw | 0.3730 | 5855.7910 | 34,290,283.0000 | 4587.3390 | 13/10/2025 |

| 420 | 17/05/2023 | 27/01/2025 | log | 0.5516 | 0.0410 | 0.0017 | 0.0314 | 14/10/2025 |

Table 19.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil (Complete Data): Rolling-window early-warning summary.

Table 19.

IBOVESPA Index, Brazil (Complete Data): Rolling-window early-warning summary.

| Window End | N Fits | Median | p25 | p75 | Lead (TD) | Risk |

|---|

| 07/08/2024 | 2 | 20/09/2024 | 08/09/2024 | 02/10/2024 | 30.4926 | Beyond60 |

| 28/08/2024 | 2 | 12/09/2024 | 05/09/2024 | 19/09/2024 | 11.0952 | High |

| 18/09/2024 | 2 | 19/10/2024 | 29/09/2024 | 19/10/2024 | 15.1910 | Elevated |

| 10/10/2024 | 2 | 17/10/2024 | 15/10/2024 | 19/10/2024 | 6.6109 | Very High |

| 31/10/2024 | 2 | 08/12/2024 | 03/12/2024 | 13/12/2024 | 25.5182 | Elevated |

| 22/11/2024 | 2 | 31/05/2025 | 26/03/2025 | 24/08/2025 | 40.4887 | Beyond60 |

| 13/12/2024 | 2 | 19/09/2025 | 25/08/2025 | 13/10/2025 | 42.1350 | Beyond60 |

| 20/01/2025 | 2 | 10/11/2025 | 30/10/2025 | 21/11/2025 | 43.3414 | Beyond60 |

Table 20.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Complete Data): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants.

Table 20.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Complete Data): LPPL results across candidate windows and variants.

| L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | | | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|

| 180 | 29/04/2024 | 15/01/2025 | raw | 0.900 | 9.936 | 0.721 | 388.396 | 280.399 | 13/03/2025 |

| 180 | 29/04/2024 | 15/01/2025 | log | 0.900 | 8.685 | 0.748 | 0.020 | 0.016 | 28/02/2025 |

| 240 | 01/02/2024 | 15/01/2025 | raw | 0.900 | 10.908 | 0.817 | 359.037 | 268.939 | 03/04/2025 |

| 240 | 01/02/2024 | 15/01/2025 | log | 0.900 | 11.441 | 0.833 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 04/04/2025 |

| 300 | 03/11/2023 | 15/01/2025 | raw | 0.900 | 9.280 | 0.907 | 364.320 | 267.278 | 17/03/2025 |

| 300 | 03/11/2023 | 15/01/2025 | log | 0.900 | 7.372 | 0.925 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 07/04/2025 |

| 360 | 10/08/2023 | 15/01/2025 | raw | 0.900 | 11.137 | 0.927 | 396.731 | 295.110 | 10/04/2025 |

| 360 | 10/08/2023 | 15/01/2025 | log | 0.900 | 9.084 | 0.943 | 0.020 | 0.016 | 06/03/2025 |

| 420 | 15/05/2023 | 15/01/2025 | raw | 0.900 | 10.635 | 0.927 | 413.753 | 308.897 | 28/01/2025 |

| 420 | 15/05/2023 | 15/01/2025 | log | 0.900 | 10.535 | 0.941 | 0.021 | 0.017 | 28/03/2025 |

Table 21.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Complete Data): Baseline calibration (selected window).

Table 21.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Complete Data): Baseline calibration (selected window).

| L (TD) | Window Start | Window End | Variant | | RMSE | MSE | MAE | |

|---|

| 360 | 10/08/2023 | 15/01/2025 | raw | 0.9269 | 396.7309 | 157,395.4396 | 295.1096 | 10/04/2025 |

| 360 | 10/08/2023 | 15/01/2025 | log | 0.9431 | 0.0200 | 0.0004 | 0.0155 | 06/03/2025 |

Table 22.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Complete Data): Rolling-window early-warning summary.

Table 22.

NYSE Composite Index, U.S.A (Complete Data): Rolling-window early-warning summary.

| Window End | N Fits | Median | p25 | p75 | Lead (TD) | Risk |

|---|

| 07/08/2024 | 2 | 31/10/2024 | 31/10/2024 | 31/10/2024 | 59.76 | Beyond60 |

| 28/08/2024 | 2 | 10/10/2024 | 19/09/2024 | 31/10/2024 | 30.57 | Beyond60 |

| 19/09/2024 | 2 | 14/11/2024 | 31/10/2024 | 28/11/2024 | 40.02 | Beyond60 |

| 10/10/2024 | 2 | 03/12/2024 | 16/11/2024 | 20/12/2024 | 37.10 | Beyond60 |

| 31/10/2024 | 2 | 01/12/2024 | 30/11/2024 | 02/12/2024 | 21.54 | Elevated |

| 21/11/2024 | 2 | 13/12/2024 | 08/12/2024 | 18/12/2024 | 14.08 | Elevated |

| 13/12/2024 | 2 | 02/02/2025 | 24/01/2025 | 11/02/2025 | 32.97 | Beyond60 |

| 07/01/2025 | 2 | 11/03/2025 | 05/03/2025 | 17/03/2025 | 43.32 | Beyond60 |