1. Introduction

First discussed by

Bowen (

1953), the issue of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has been extensively examined by academic researchers and finance practitioners alike (e.g.,

Baid and Jayaraman 2022;

Berk et al. 2023;

de Vincentiis 2023;

Friede et al. 2015;

Galema and Gerritsen 2025;

Potharla et al. 2024;

Riyadh et al. 2024). The central debate has focused on whether those firms that prioritize social responsibility— that is, those that deliberately allocate resources toward meeting the interests of stakeholders, employees, and the broader public—ultimately achieve superior long-term financial performance, or whether such ethical commitments potentially constrain profitability. Empirical evidence suggests that CSR considerations do influence investment decisions, and that this area of inquiry continues to attract sustained academic and practitioner interest. With the increasing availability of CSR ratings data, particularly those based on the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) dimensions (

United Nations 2004), investors have become more informed and attentive to corporate sustainability practices. While some studies suggest that firms embracing CSR are rewarded by investors and other stakeholders, others provide contradictory evidence, leaving the debate ongoing and unresolved. Furthermore, recent research concludes that ESG-related signals may be interpreted very differently across markets and contexts, sometimes producing opposite market reactions (

de Vincentiis 2023), while CSR practices themselves can generate contrasting outcomes that complicate the link between sustainability and financial performance (

Riyadh et al. 2024).

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) investors typically rely on ESG scores as a central criterion for asset selection. This preferential allocation of capital may contribute to an improvement in the Corporate Financial Performance (CFP) of socially responsible firms, as they tend to attract greater investment flows from large financial institutions and asset managers employing SRI strategies. A United Nations report indicates that, as of June 2024, more than USD 128 trillion in assets were managed by organizations that align their investment approaches with CSR- and ESG-based standards (

Principles for Responsible Investment Association 2024). The latest biennial Global Sustainable Investment Review 2024 finds that the value of fund assets reporting the use of responsible or sustainable investment approaches has reached USD 16.7 trillion, increasing by almost 49% over the last two years, and representing approximately 27% of the fund market of funds domiciliated in Europe, the United States, Japan, Canada, and Australasia (

Global Sustainable Investment Alliance 2025). This increasing investor interest on ESG is consistent with recent evidence that sustainability-related rating changes and ESG momentum can have measurable effects on stock valuations across different markets (

Berk et al. 2023;

Escobar-Saldívar et al. 2025;

Galema and Gerritsen 2025).

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) encompasses a range of internal and external factors that affect an organization’s activities and strategic decisions. It represents a critical source of information, particularly for long-term investors, regarding the risks faced by a firm and the way management responds to them (

Dahlsrud 2008). Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, which

Welford and Frost (

2006) note are typically assessed by third parties, constitute a central and more clearly defined component of CSR, with greater conceptual consensus regarding their elements than for CSR (

Widyawati 2020). ESG scores provide an external evaluation of the regulatory, legislative, operational, and reputational opportunities and risks that are relevant to investors.

Boffo and Patalano (

2020) assert that these scores carry both reputational and legal implications and may also serve as an indicator of a firm’s capacity to develop a sustainable competitive advantage. According to

de Vincentiis (

2023), ESG scores are interpreted differently in different regional contexts. Specifically, the author finds that ESG-related information does not generate uniform market reactions across major regions: European markets typically penalize negative ESG news, while in the U.S. market good news is more relevant than bad news and cause a negative price impact, and Asia-Pacific markets show no reaction at all.

Several empirical studies have reported that portfolios composed of assets with high ESG ratings often outperform their benchmarks across a range of market conditions (e.g.,

Friede et al. 2015;

Nagy et al. 2016;

Pisani and Russo 2021). In some instances, the performance of ESG-focused investments has been sufficiently strong to offset hypothetical transaction costs of up to 50 basis points per trade (

Hoepner 2013). However, other research documents an inverse relationship between ESG ratings and returns, and still other studies report no statistically significant association at all (e.g.,

Girerd-Potin et al. 2014;

Kumar 2023;

Pedersen et al. 2021). In the absence of consistency in the results, it is possible to say that, so far, this relationship remains subject to ongoing empirical analyses and debate. Recent papers reinforce this mixed picture. While ESG momentum appears to generate positive abnormal returns in European markets (

Berk et al. 2023).

Galema and Gerritsen (

2025) find that ESG downgrades are associated with negative abnormal returns in the United States, while

Escobar-Saldívar et al. (

2025) report an inverse relationship between ESG scores and stock returns in that market. These findings underline the context-dependent nature of ESG effects and their potential to vary substantially across regions. Additionally, beginning in 2017, the European Union’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) required large firms to disclose information on environmental, social, and employee-related matters (

Carnini Pulino et al. 2022), whereas in the U.S. the advancement of ESG-related regulation intensified public debate and contributed to an evident anti-ESG backlash (

Harper Ho 2024). Remarkably, the decline in excess demand for ESG assets appears to have preceded this political reaction and the subsequent introduction of state-level anti-ESG legislation (

Curtis 2025).

This study contributes to the literature by examining the relationship between CSR, reflected by ESG scores, and CFP, measured by stock returns, offering a broader perspective on the subject. More precisely, this study differs from prior work by integrating several layers—regional context, individual ESG pillars, and firm size—within a unified econometric framework. Previous studies typically examine one of these dimensions in isolation, which may help explain their divergent findings. The mixed evidence documented across markets suggests that ESG performance is priced differently depending on institutional and cultural environments, as illustrated by recent work showing that both rating changes and ESG-related news elicit different market reactions across regions. Our framework allows the joint evaluation of these mechanisms.

The study includes a total of 22,627 observations over 10 years, corresponding to an annual average of approximately 2260 companies from the thirteen European countries (EC) and the U.S. The analyses are conducted for all firms together and separately for EC and U.S. companies, contributing to uncovering regional differences in the relationship between ESG performance and corporate financial performance. These two regions were selected because of their central role in the global economy and capital markets. The United States accounts for approximately 46% of global stock market capitalization and 24% of world GDP, while the thirteen European countries included in our study represent roughly 13% of global market capitalization and more than 17% of global GDP (

International Monetary Fund 2024;

World Bank 2025). This research also considers firm size to explore relevant variations in the relationship and to provide a clearer picture of how these factors interact. To examine the relationship between stock returns and ESG scores, we employ panel regression models. The

Hausman (

1978) test results indicated that fixed-effects models were suitable for analyzing this relationship in most cases, with only a few exceptions. This regional and firm-size perspective is consistent with emerging evidence that legal, regulatory, and cultural factors, particularly the growing divergence between U.S. and European ESG frameworks (

Kuntz 2024), shape how markets evaluate sustainability information.

Li et al. (

2024) suggest that future research should examine both the independent and interactive effects of each ESG pillar on firm value—and corresponding stock returns—while paying particular attention to how these relationships vary across regions and industries.

Thus, the primary contribution of this study lies in clarifying whether ESG performance exerts a positive or negative influence on corporate financial performance through a comprehensive, multi-layered empirical design that simultaneously accounts for geographic context, firm size, and the individual ESG dimensions. By doing so, the study offers a more nuanced and integrated assessment of the ESG–CFP relationship than has been provided in prior research.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a brief review of the relevant literature,

Section 3 outlines the data and explains the research methodology,

Section 4 presents the empirical findings, and

Section 5 discusses these results and concludes the paper.

3. Research Method

To examine whether ESG and its components are equally important across the U.S. and Europe, and among Large, Mid and Small companies, the statistical analysis employs a panel regression model to the broad sample and its subsamples. Clearly, the main variables of interest are the ESG score and its individual components (ENV, SOC, and GOV). We used Python version 2.12 for all the data gathering, data preparation and econometric analysis.

The data used in this study was obtained by LSEG’s Eikon platform via its Python API, including the ESG scores which are now an evolution of the original Asset4 ESG ratings (

Refinitiv 2023). Asset4’s scores have a range of 0 to 100 and are frequently represented with letter-ratings from D− to A+ based on percentile ranges of equal size. The model represented by Equation (1) is used to carry out all the analyses. VarInt represents either ESG, ENV, SOC or GOV, since the variables of interest were included only one at a time given the high correlations among them. All the stocks in the study have ESG scores as well as annual data for all the variables listed in

Table 1, covering the entire period under examination. The control variables listed in

Table 1 were selected based on the common multifactor models used to explain stock returns (

Fama and French 1993,

2015).

The dataset includes 22,627 entity–time observations spanning a ten-year period from December 2014 to December 2023. These observations cover two regions, with 13,624 corresponding to the United States and 9003 to European countries. The firms in the sample can also be grouped by size, with 6865 observations classified as Large-Caps (market capitalization above

$10 billion USD), 8644 observations as Mid-Caps (market capitalization between

$2 and

$10 billion USD) and 7118 as Small-Caps (market capitalization between

$250 million and

$2 billion USD).

Table 2 presents the observations of firms by Region-Size combination through the 10 years analyzed and

Table 3 shows the distribution of stocks per GICS sector in the combined U.S. and EC sample. The countries included in the European region subsample are, with total observations in parentheses: Belgium (287), Denmark (256), Finland (299), France (1060), Germany (1133), Italy (463), the Netherlands (334), Norway (330), Poland (189), Spain (407), Sweden (822), Switzerland (759), and the UK (2664). There are other countries in the European region, but we included the ones that had at least 15 observations per year. Austria and Greece meet this requirement only since 2020 and other countries like Portugal or Ireland did not meet this constraint.

To avoid survivorship bias, we must include data for firms that existed for only part of the study period. This inherently results in an unbalanced panel. Creating a balanced panel by only including stocks that existed for the entire period would intentionally re-introduce survivorship bias. The primary risk of using an unbalanced panel comes from the reason that causes the data to be missing. Mainly if this is a non-random mechanism there could be some type of sample selection bias. In our case, we are using a very large dataset that only filters stocks based on their country of exchange and minimum market capitalization (above micro caps). Given that the number of stocks increased naturally over time due to more stocks being listed than the ones being delisted, standard panel data regression models like FE and RE are robust and can be applied to our data.

As a first step, the analysis tested the pair-wise correlations among the variables to identify any potential multicollinearity issues. The correlations are shown in

Table 4 below, with magnitudes larger than 0.20 in bold. Correlations between ESG components are high, especially between the Environmental (ENV) and Social (SOC) components (0.74), whereas the correlation with the Governance (GOV) component is also considerable (0.38). In view of these results, the study examines each of the three pillars independently in the regressions rather than simultaneously. Another relevant correlation between variables is that of Size and the ESG components (0.45), an expected result since larger companies have greater slack to invest in ESG initiatives. Nevertheless, the literature identifies Size as an important control variable (

Fama and French 1993,

2015). Consequently, we include it in the model, as its correlation with the ESG variables is below 0.5 and variance inflation factor tests yielded values lower than 4.

4. Results

The analysis divides the sample by region and size categories to compare their differences, resulting in 12 different sub-samples: one full sample that includes both regions (U.S. and EC) and all firm sizes (Large-, Mid-, and Small-Cap), two sub-samples based on region, three sub-samples based on firm size, and six sub-samples based on pairwise combinations of region and firm size.

We performed VIF tests for all subsamples to test for multicollinearity. We found, as expected given the pair-wise correlations, that the largest VIF occurs with the Size factor in all cases. However, we consider that the VIF is acceptable in all the AllCap, SmallCap and MidCap models (Max VIF < 3.5). In the LargeCap models we do find larger VIF values with relation to the Size variable (Max VIF > 5). However, given the importance of the Size factor in the literature we decided to keep it and maintain the same variables in all cases, for comparison.

Table 5 shows a summary of the residual diagnostics tests that were also performed for all models.

In view of the above econometric considerations, the methodological approach leaned toward Panel regression models, with both Fixed Effects (FE) and Random Effects (RE). Each of these models has its advantages and limitations due to their underlying assumptions. The FE model removes the effect of time-invariant characteristics of the stocks and other unobserved factors, which addresses this type of potential endogeneity and allows the evaluation of the net effect of the exogenous variables on the dependent variable. Alternatively, the RE model incorporates time-invariant variables (e.g., Sector), by modelling constant terms as randomly distributed across cross-sectional units. However, this holds true only if the individual effects are strictly uncorrelated with the regressors. A disadvantage of the RE model is the difficulty in specifying all the individual characteristics that may influence the dependent variable, leading to a potential omitted variable bias that could cause endogeneity. To determine whether the FE or RE models are more appropriate, we conducted Hausman tests for each case. The null hypothesis of the Hausman test asserts that unique errors are uncorrelated with the regressors, and if it holds true then the RE model is consistent and efficient. However, if the null hypothesis is rejected, the FE model is preferred as its coefficients are consistent.

Table 6 shows that the Hausman test rejected the null hypothesis in 39 cases, leading to the selection of the FE model in such instances, while selecting the RE model in 9 of the cases.

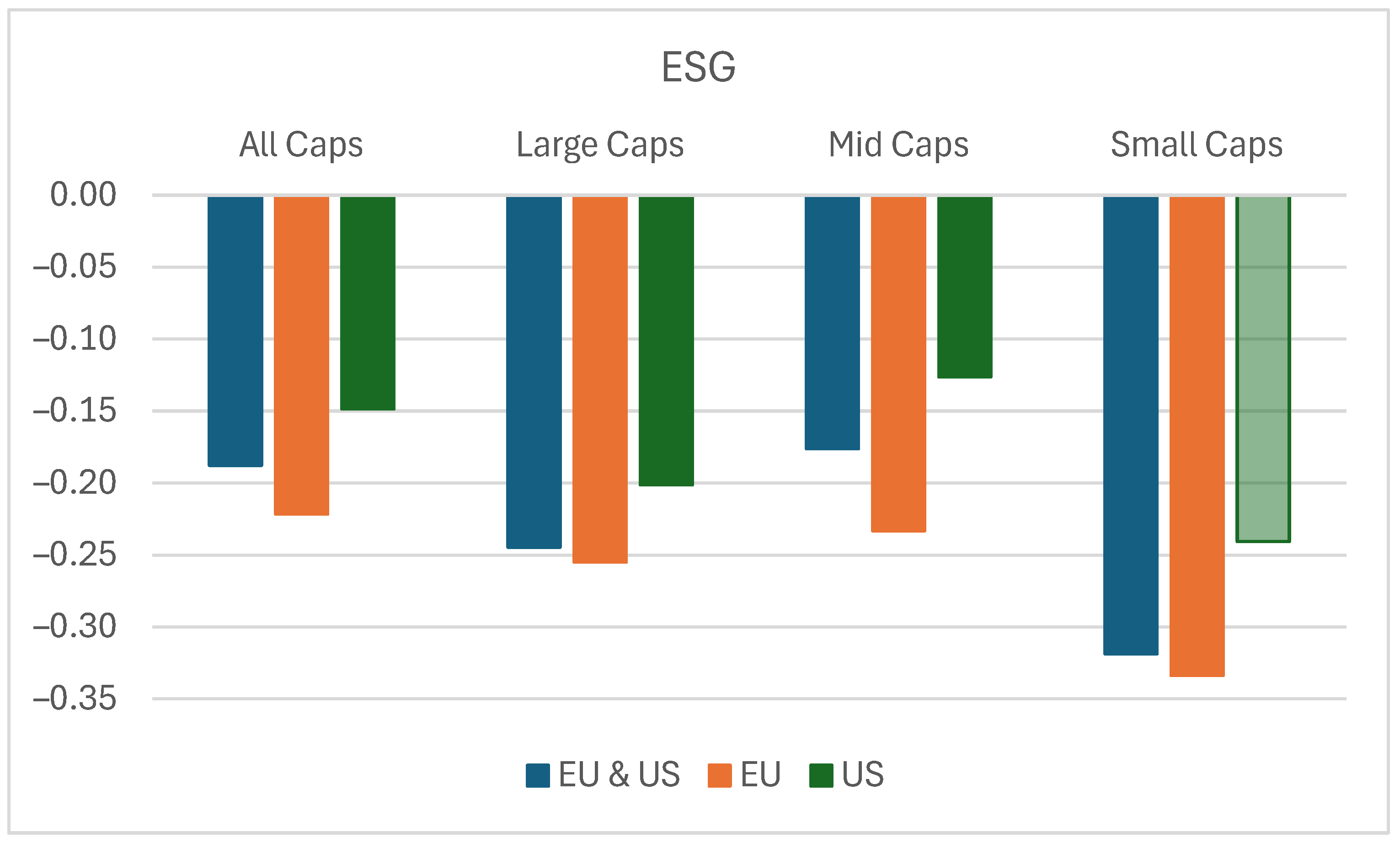

The results in

Figure 1 reveal that ESG is a relevant variable in all financial models, regardless of region and company size. In the U.S. Small-Cap sample, it shows slightly weaker significance but preserves a negative sign, consistent with the other samples (i.e., the higher the ESG score the lower the return on a company’s stock). The literature suggests that following ESG policies decreases returns because it implies added costs for companies. However, an advantage of ESG is risk reduction and higher-quality investments which, in turn, lead to lower required returns and higher stock valuations. Furthermore, since there is stronger public coverage of firms as they increase in market capitalization, it makes sense for Small-Cap stock returns to be less influenced by ESG ratings.

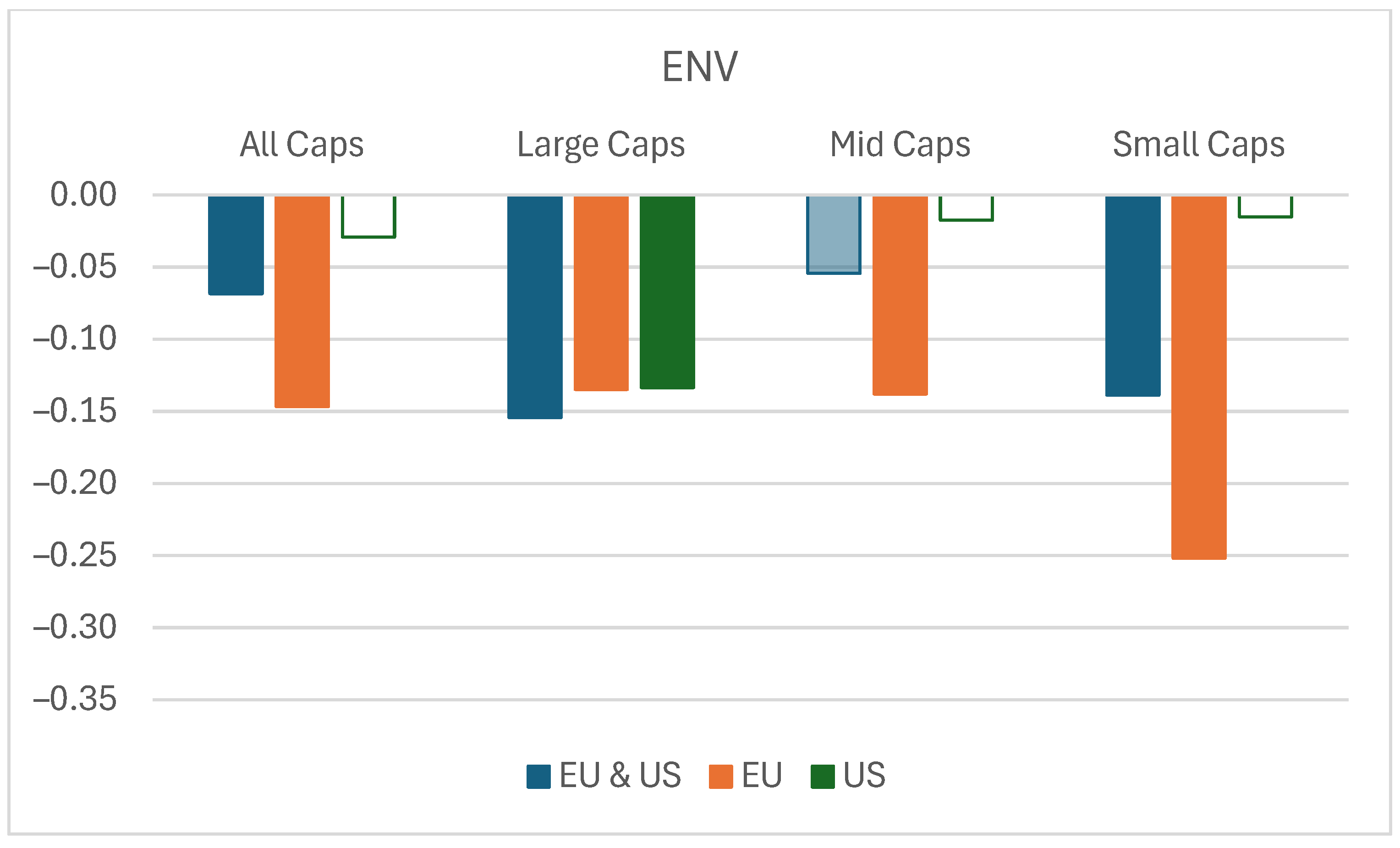

Figure 2 reveals that the Environmental pillar (ENV) is also relevant by itself in the combined European and U.S. sample. However, when examining the regions separately, ENV appears to be considerably more relevant in European countries across different firm sizes than in the US, where it is only relevant in Large-Caps. This regional difference is not surprising, given that European countries have introduced more rigorous policies for cleaner energy sources, either out of conviction or necessity, while the U.S. seems to have a more divided stance (

Li et al. 2025). European firms are subject to a more requiring regulatory framework on ESG compared to the U.S. companies (

Fox et al. 2024). Moreover, as of 2021, Europe was the largest climate-fund market, as implied by

Ma et al. (

2024). However, ENV is still significant in the U.S. Large-Caps sample, which is logical given that many of those companies are global firms and must adhere to international regulations. Additionally, these companies are more visible and closely monitored by the public and media, making it advantageous for them to be socially responsible in the three ESG pillars.

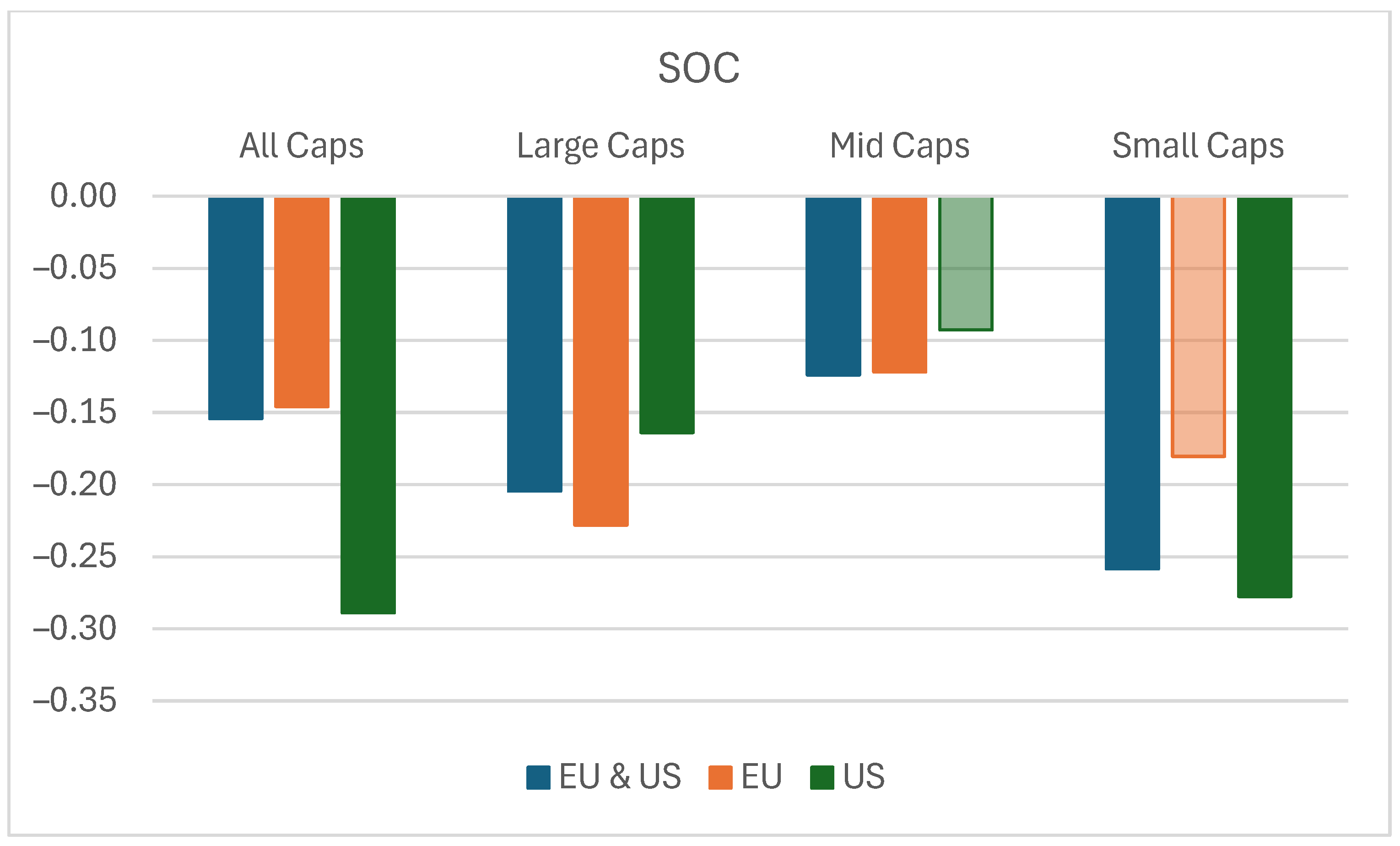

As shown in

Figure 3, the Social pillar (SOC) is relevant across all regions and firm size combinations. In Europe, it is only slightly weaker in Small-Caps, which aligns with the public coverage argument mentioned earlier. In the case of the US, the SOC variable is slightly weaker in Mid-Caps but remains significant at the 10% level, while its negative sign and magnitude are consistent with its coefficient in other samples. Although

Table 4 shows a high correlation between the ENV and SOC pillars (0.74) and a strong correlation between both pillars and the overall ESG scores (0.86 and 0.89 respectively), the SOC pillar results resemble the ESG results more closely, while the ENV results do show regional differences in Mid- and Small-Cap firms.

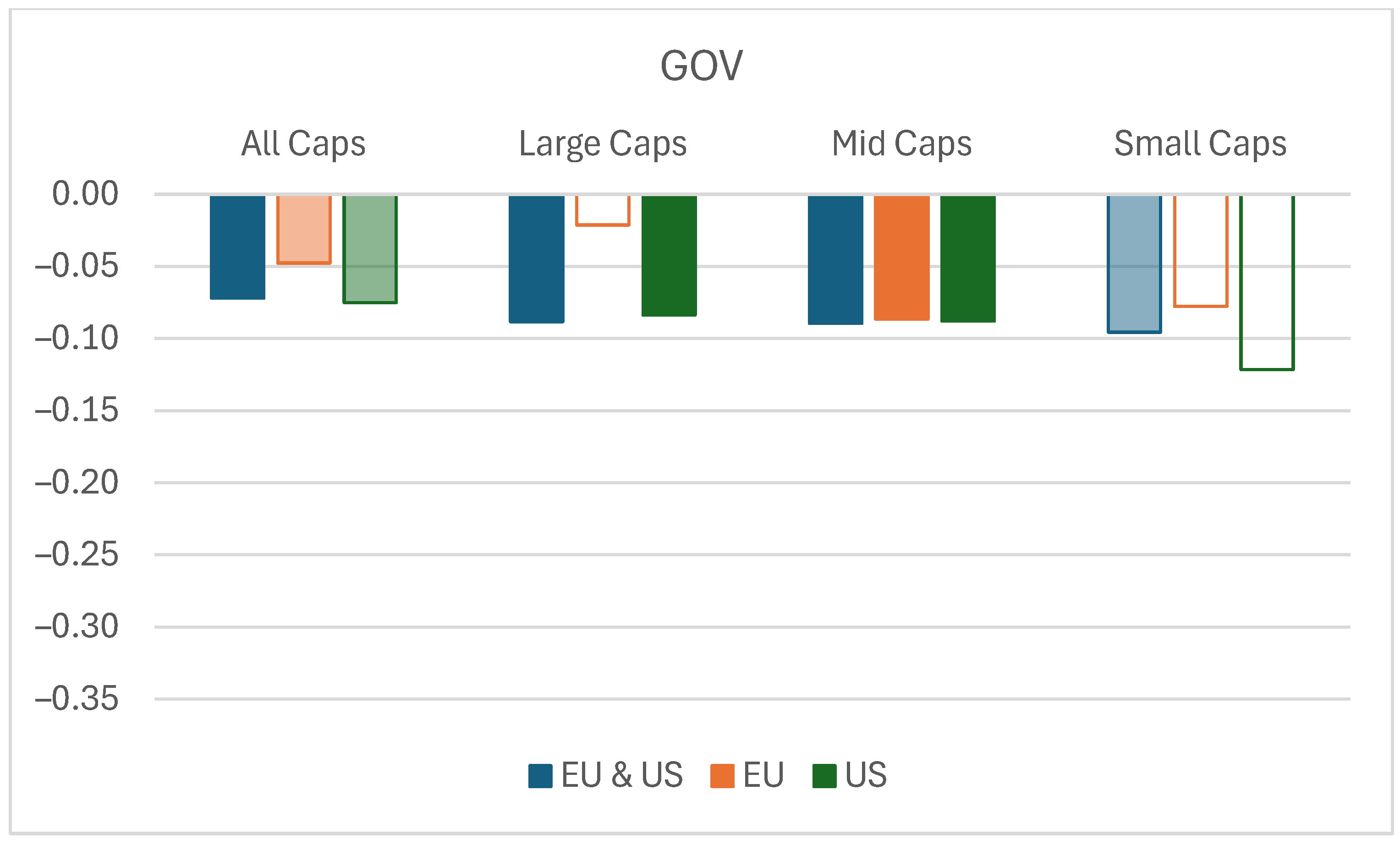

Figure 4 suggests that the Governance pillar (GOV) is not significant in Small-Caps stock returns, except at the 10% level in the combined sample. This finding may be a consequence of the increased sample size.

Eun and Resnick (

2018) assert that with a large managerial ownership, the interests of managers and outside investors become better aligned, thus reducing agency costs. We suggest that many Small-Caps still have founders as managers, making them less susceptible to agency problems compared to their larger counterparts.

In contrast, GOV is significant in both regions for the combined and Mid-Cap samples. The significance of Governance for Mid-Cap returns in both Europe, and the U.S. may stem from these firms being in a growth stage, which increases uncertainties about their future. Therefore, effective governance policies and practices may be particularly important for maintaining investor confidence in these companies.

Eun and Resnick (

2018) also signpost an interim range of managerial ownership share over which there is an “entrenchment effect”. If managerial ownership is still large but below a certain threshold, it might be able to extract larger private benefits at the expense of outside investors, while still being able to resist takeover bids.

Interestingly, GOV is significant in the case of U.S. Large-Caps but non-significant in the case of European Large-Caps. This result aligns with the arguments proposed by

Eiteman et al. (

2013) who assert that in the case of US, management typically serves as a hired agent of widely held firms, owning only a small proportion of stock in their firms. In contrast, many firms in other global markets are characterized by controlling shareholders such as family-controlled firms (e.g., France and Italy), institutions like banks (e.g., Germany), governments or other consortiums of interests. These controlling owners tend to prioritize the long term, and being closer to management, they face fewer conflicts and agency problems. In this context,

Kirchmaier and Grant (

2005) found that governance contributes to performance differences between European and U.S. firms. Hence, having good governance practices might be more relevant in the U.S. to keep management in check than in Europe. Additionally,

Li et al. (

2025) find that there during this period there has been a stronger diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) push in the USA than in Europe, which is typically captured in Governance measures. The sign of the GOV variable remains negative in all cases, however, consistent with other ESG variables.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examines the relationship between overall ESG performance and its three individual pillars and the stock returns of large-, medium-, and small-capitalization firms in the United States and in a sample of thirteen European countries. A key contribution of the study lies in its multi-layered analytical design, which goes beyond an aggregate perspective by independently evaluating each combination of region and firm size, thereby providing a more in-depth and comparative analysis of how ESG-related factors are reflected in equity performance across different market and institutional contexts.

The results of the study consistently indicate a negative relationship between ESG, each of its components, and stock returns, aligning with findings from previous research (e.g.,

de Vincentiis 2023;

Escobar-Saldívar et al. 2025;

Villarreal-Samaniego et al. 2022). These outcomes line up with two well-established mechanisms in the literature, namely, the risk-mitigation channel, which suggests that stronger ESG practices reduce firms’ exposure to idiosyncratic and tail risks, thereby potentially lowering the required risk premium and average returns (

Giese et al. 2019), and the cost channel, which claims that sustainability initiatives involve operational and compliance costs that may depress short-term profitability and stock performance (

Jyoti and Khanna 2021;

Menicucci and Paolucci 2023). While we acknowledge that the negative relationship between ESG and stock returns may reflect a mixture of reduced risk premia and higher ESG-related costs, further research is warranted to determine whether the negative coefficients in our results are driven primarily by one channel or a combination of both.

The influence of both ESG and the individual pillars on stock returns is generally robust across the full sample of European and U.S. companies included in this study, as summarized in

Table 7. An exception, however, is the governance pillar for small-capitalization firms. This finding also holds true when U.S. and European firms are examined separately. This result likely stems from the ownership structure of Small-Caps, where owners often act as managers, thereby reducing agency problems. On the other hand, the study found that GOV is significant for both European and U.S. medium-capitalization companies’ stock returns. Since these firms are in a growth stage, there are concerns regarding their future performance. Consequently, internal practices and policies, such as governance, may be particularly relevant to investors interested in these companies. Furthermore, while GOV proved significant for Large-Cap firms in the US, it was not for large European firms. Unlike many large U.S. companies, where managers frequently act as agents, managers and shareholders in large European firms are family members, banks, or governments. These divergent ownership structures may help explain the difference in the significance of GOV for U.S. and European Large-Caps.

Another regional difference can be observed in the environmental component of ESG, which appears to have a more significant impact on European companies’ stock returns than on U.S. companies. This is likely due to stricter European regulations on environmental sustainability and a larger European climate-fund market. While U.S. large-cap companies are also influenced by ENV, their global operations and increased public scrutiny may contribute to their ESG focus. The regional differences found in our study align with Legitimacy Theory, since firms operating in different institutional environments face distinct societal expectations and regulatory pressures. Specifically, European companies may be compelled to adopt stronger environmental practices to maintain legitimacy in markets where sustainability standards are more deeply embedded.

This study documents a consistent negative association between ESG scores, their individual pillars, and stock returns across regions and firm size groups. However, the analysis does not allow for causal inference, and the findings should be interpreted as associational. In addition, although the analyses were estimated separately for the U.S., Europe, and firm-size groups, we did not formally test whether the estimated coefficients differ statistically across these subgroups. Such tests represent a natural extension of the present study. Future research could incorporate these formal comparisons and explore identification strategies that more directly isolate the causal mechanisms underlying ESG–return relations.

The findings in this paper are relevant to both practitioners and policymakers. For practitioners, the consistent negative association between ESG scores and stock returns suggests that portfolio creation should carefully account for how ESG attributes alter expected risk–return trade-offs across regions and firm sizes. Specifically, investors who rely on ESG screens or integrate ESG-tilted strategies may need to adjust the weighting of ESG-intensive assets to maintain portfolio allocations that are compatible with their target risk-return profiles. The stronger pillar-specific effects observed in certain market segments further suggest that active managers should evaluate ESG dimensions individually rather than rely solely on aggregate scores. For policymakers, the cross-regional differences identified in this study underscore the importance of harmonizing disclosure standards and supporting regulatory mechanisms that enable pension funds and long-horizon institutional investors to incorporate ESG criteria without compromising their mandate to maximize beneficiaries’ long-term returns.

More research is required to examine whether these results apply in other contexts, such as emerging market firms or specific industrial sectors, and to clarify whether the negative association between ESG, its components, and stock returns is driven primarily by lower profitability or by reduced risk. Future work could incorporate dynamic panel specifications or time-varying models to capture adjustment processes in the ESG–return relationship, and explore potential nonlinearities, for example, threshold or quantile models that assess different effects at low versus high ESG levels. In addition, formal statistical tests for differences across regions and firm-size groups, based on pooled models with interaction terms, would complement the separate estimations presented here. Finally, studies that examine regulatory or institutional changes—such as shifts in ESG disclosure requirements or the introduction of pro- and anti-ESG policies—as quasi-natural experiments could help identify the causal mechanisms underlying ESG–CFP relations more precisely.