1. Introduction

The audit profession is key to financial transparency and public trust (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025). Yet in recent years, a worrying global trend has appeared: the number of qualified auditors is falling (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025). Many countries report shortages and fewer new entrants into the profession (

Ellis 2022;

Khumalo 2023;

Tyson 2023;

Yiu and Zhong 2023). For example, in the United States, more than 300,000 accountants left their jobs in just two years, shrinking the workforce by 17% (

Ellis 2022). In Australia, the number of registered company auditors dropped by over 30% in the past decade, linked to demographics, firm mergers, and an aging workforce (

Hecimovic et al. 2009). Young professionals across countries are avoiding auditing careers because of long hours, heavy regulations, and work–life balance worries (

Harber 2018). These global pressures, regulatory demands, talent shortages, firm closures, and audit market mergers make it harder for the audit profession to remain sustainable (

Ramalepe 2023;

Ahn et al. 2024;

Tyson 2023;

Vien 2024;

Eldaly 2012;

Fülöp and Pintea 2014). While numbers on auditor shortages are well documented, little research has explored how practitioners themselves experience these shortages, especially in South Africa. This study fills that gap by looking beyond statistics to the lived impact on professionals.

South Africa reflects global trends, with clear signs of a drop in its registered auditor (RA) population (

IRBA 2024a). Data from the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (IRBA) show that RA numbers in South Africa fell by about 11.7% between 2019 and 2023 (

IRBA 2023). This decline comes from many factors, such as auditors retiring faster than replacements can be trained, and fewer young accountants choosing auditing (

IRBA 2024a). The profession struggles to draw new talent, partly because of negative views linked to corporate scandals and the tough nature of audit work (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025). South African auditors also face more regulatory pressure (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025). After audit failures, regulators have tightened oversight and IRBA inspections in recent years (

IRBA 2024b). These steps aim to rebuild trust, but they also raise compliance costs and liability risks for auditors (

Celestin 2020a). Smaller audit firms especially feel the strain of higher standards and tighter oversight (

Celestin 2020b). Many small and mid-size firms cannot carry these burdens, leading some to merge with bigger firms or exit the assurance market (

Celestin 2020b). This trend of consolidation further shifts the market toward the Big Four, raising concerns about weaker competition and less capacity to serve the public interest (

Celestin 2020b). In short, by 2025, the South African audit field will face a shrinking workforce and rising issues of audit quality, keeping talent, and firm survival (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025;

Harber 2018). The aim of this study was to assess how the decline of RAs will affect the future of the assurance industry in South Africa. A qualitative approach was used, with structured interviews conducted with eight RAs currently registered with the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (IRBA), the national audit regulator. IRBA was once ranked number one for seven straight years, from 2010 to 2016, in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report for the strength of its auditing and reporting standards (

IRBA 2016). However, since 2017, IRBA’s standing has dropped because of major scandals such as Steinhoff, VBS Mutual Bank, and Tongaat Hulett, which have damaged public trust (

IRBA 2017;

Ramsarghey and Hardman 2020). Even so, IRBA remains influential worldwide. This is shown by the recent re-election of its CEO, Mr. Imre Nagy, as board member and chairperson of the IFIAR Audit and Finance Committee. Along with Ireland (IAASA), Poland (PANA), Singapore (ACRA), and South Africa (IRBA), he was appointed to the IFIAR Board for a four-year term, joining 12 other jurisdictions to form a 16-member board (

IRBA 2025). This highlights that IRBA is still relevant and among the leaders in global auditing. Therefore, this study is important not only for South Africa, but also internationally, as similar challenges may be present in other countries.

The central research question guiding this inquiry is: How will the decline in Registered Auditors affect the assurance industry in the future within the South African economy? This study aims to:

Describe professional concerns about the decline in RAs in South Africa.

Explain the drivers of RA decline between 2019 and 2023.

Document firm-level strategies adopted to adapt to changes in RA numbers.

Examine regulatory challenges shaping audit practice and their perceived proportionality.

Assess near-term risks (5–10 years) for capacity, quality, and market structure.

Identify opportunities for growth and improvement in the profession.

Examine strategies to sustain the RAs in the midst of a decline.

This study looks at a serious and growing problem: the shortage of assurance auditors, which is putting more pressure on the capacity, quality, and sustainability of assurance services in the country. By speaking directly with experienced professionals through in-depth interviews, the research gathers practitioner insights on how this shortage is changing audit practice, firm resilience, and public trust in financial reporting. The results provide a grounded and forward-looking view of the risks, challenges, and possible responses to the auditor shortage. Importantly, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is one of the first qualitative investigations into the future impact of declining RAs in South Africa and, as noted earlier, may also add value to debates in other countries. It contributes to the wider discussion on the future of the assurance profession, providing evidence-based insights that can guide policy, regulatory reform, and professional development strategies to support the audit industry in a more constrained environment. The next sections of the article present the literature review, methodology, analysis and discussion of results, and the conclusion. The conclusion covers the study’s contribution, its limitations, recommendations for practice and policy, and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

This section offers an overview of previous researchers’ findings and identifies gaps in the existing research. Furthermore, it establishes a foundation for the theoretical studies upon which this thesis is based.

2.1. Theoretical Review: Behavioural and Institutional Theory

The Behavioural Theory, and more specifically the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) developed by

Ajzen (

1991), supports this study. According to TPB, human behaviour is shaped by three main components: behavioural beliefs, normative beliefs, and control beliefs. Behavioural beliefs relate to expected outcomes (positive or negative) of a behaviour, which influence an individual’s attitude. Normative beliefs involve perceived social pressures or expectations from others. Control beliefs reflect how easy or hard the individual thinks the behaviour will be, shaped by past experiences and possible obstacles (

Ajzen 1991).

This theory fits the auditing profession in the South African setting. It provides a way to explain the falling interest in becoming an RA, especially among young professionals. For instance, behavioural beliefs may be affected by the perceived risks, strict regulatory oversight, or tough working conditions in the profession. Normative pressures may reflect social and professional expectations placed on auditors. At the same time, control beliefs may come from the perceived difficulty of qualifying, meeting performance demands, or staying independent under rising compliance requirements.

As this study aims to assess how the decline in RAs may affect the future of the assurance industry, behavioural theory helps explain why auditors are leaving or avoiding the profession. It offers a psychological framework for understanding the motivations, barriers, and career choices that reduce the supply of RAs. This decline then directly affects audit firm capacity, assurance quality, and the long-term sustainability of the industry.

Institutional theory provides a way to understand how audit firms react to outside influences, such as regulatory demands, professional expectations, and pressures from global markets (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025).

Scott (

2013) highlights three types of institutional pressure: coercive, normative, and mimetic, which guide and limit how organisations behave. These pressures are important when looking at the global shortage of auditors, as firms deal with technological change, complex regulations, and workplace restructuring to handle uncertainty and stay legitimate (

Malsch and Gendron 2011;

Fülöp and Pintea 2014). Therefore, the theory offers a useful framework for studying how changing institutional contexts affect the long-term survival of the audit profession (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025).

2.2. Empirical Review

The decline of Registered Auditors (RAs) in South Africa has become a critical concern within the auditing profession, raising questions about the future capacity and credibility of the assurance industry (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025). This section primarily reviews empirical studies published between 2019 and 2025, a period chosen due to the documented significant decline in Registered Auditors from 2019 onwards and the forward-looking scope of this study, which extends to 2025. However, we also incorporate foundational works, such as the 2018 study by Harber, for historical context, which explored the initial indications of RA decline and highlighted issues that have persisted and intensified in the current landscape. This section reviews empirical studies that explore the causes of this decline, its implications for audit quality, firm sustainability, regulatory pressure, and technological transformation. The literature further identifies key gaps in the South African context that this study seeks to address.

An empirical study by

Harber (

2018) is one of the earliest South African investigations into the decline in RAs.

Harber (

2018) found that growing public misunderstandings of the audit profession, increased regulatory scrutiny, and higher litigation risk were key deterrents. He also noted that audit professionals were concerned about heavier workloads, job complexity, and regulatory overreach issues that have continued and worsened in later years (

Harber 2018). However, Harber’s study predates several major developments, such as the removal of Mandatory Audit Firm Rotation (MAFR) (

Mantshantsha 2023), the rise in post-COVID global mobility, and IRBA’s stricter penalty enforcement. Therefore, there is a clear need to revisit this topic in the current context.

Ahn et al. (

2024) studied how the global shortage of accounting graduates has affected the talent pipeline in audit firms. They found that many firms are recruiting beyond traditional universities, which has been linked to lower audit quality (

Ahn et al. 2024). A similar trend is seen in South Africa, where low interest in audit careers has made the RA designation less attractive (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025). This shows that declining enrolments and a changing labour market are global challenges threatening the profession’s future (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025).

Knechel et al. (

2021) further examined auditor retention by studying the effects of high turnover in public accounting. Their findings showed that firms losing top-performing auditors faced client losses and lower audit quality, especially in complex engagements (

Knechel et al. 2021).

The problem is worsened by increasing regulatory compliance and workload pressures (

Caseware 2024).

Persellin et al. (

2019) found that auditors reported that heavy workloads, tight deadlines, and staff shortages reduced audit quality, weakened professional judgment, and lowered job satisfaction. The stress and time pressure, especially during peak season, continue to push auditors to leave the profession early (

Persellin et al. 2019).

Cpa Ireland (

2023) provides further insight into how the global regulatory environment affects small audit firms. The report warns that by 2030, many sole practitioners may leave the audit market due to rising compliance costs and complex auditing standards (

Cpa Ireland 2023). It calls for proportional audit standards for Less Complex Entities (LCEs), a view shared by many South African auditors trying to balance regulatory duties with operational sustainability (

Cpa Ireland 2023).

Similarly, the

Financial Reporting Council (

2024) report highlights a steady decline in registered audit firms in the UK, attributing this to consolidation and smaller firms exiting the market.

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) confirm that many small and mid-tier firms are leaving audit work because complex standards are not suited for SME audits. These trends mirror the South African context, where audit market concentration is rising, and smaller firms struggle to survive in an environment favouring larger players (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025).

The technological transformation of audit work adds further complexity (

Caseware 2024).

Han et al. (

2023) examined how AI, blockchain, and data analytics are changing audit procedures. They concluded that while automation boosts efficiency, it also requires new skills from auditors, creating a gap between traditional training and emerging audit demands (

Han et al. 2023). This challenge is particularly significant for smaller South African firms that lack the resources or capital to invest in advanced technologies and staff upskilling.

Caseware (

2024) highlights these challenges, reporting that nearly 90% of audit teams worldwide struggle to attract and retain qualified auditors. The report notes that data analytics is used in 78% of audits, while skills in data science (18%), IT auditing (15%), and cybersecurity (12%) are increasingly required. It also emphasises that internal audit teams are expected to do more with fewer resources, adding pressure on existing professionals and accelerating burnout, a trend also seen among South African RAs (

Caseware 2024).

In summary, empirical literature shows that the auditing profession faces significant strain from talent shortages, heavy workloads, regulatory pressures, and digital transformation. While the causes and effects of RA decline are well-documented globally, few studies have examined these issues from the perspective of South African RAs. This study addresses this gap by engaging eight practising RAs to gain qualitative insights into how these challenges are experienced locally and how they may affect the future of the assurance profession.

3. Methodology

This study used a qualitative approach, structured with the Delphi methodology to ensure alignment across research philosophy, strategy, design, data collection, and analysis. Data were collected through interviews and analysed using descriptive and thematic methods to meet the study’s objectives.

3.1. Research Philosophy

This study adopts a pragmatic research philosophy, which allows flexible, real-world approaches to explore complex issues. Pragmatism fits the study’s aim of assessing the practical impact of declining Registered Auditors (RAs) on the assurance industry. Because the study is exploratory, a qualitative approach was chosen to gather detailed insights from experienced auditors. Inductive reasoning is used, allowing conclusions to be drawn from themes that emerge from participants’ responses.

3.2. Research Design

A Delphi-based qualitative design was used to gain expert consensus on the implications of the auditor shortage. The Delphi method is well-suited for emerging or underexplored issues where expert judgment is critical. It involves multiple rounds of structured input from a panel of subject-matter experts to reach shared understandings or identify differences. In this study, the Delphi process was conducted in two rounds to allow iterative reflection and refinement of participants’ views.

3.3. Research Sample

The study focused on RAs in South Africa, identified through outreach to firms listed on IRBA’s website. Structured, open-ended interviews were conducted between 1 March 2025 and 27 May 2025 via recorded Zoom calls, with responses transcribed and prepared for qualitative coding. For transparency, the interview questions are set out in

Appendix A.

Although the original target was 14 participants (

Harber 2018), thematic saturation was reached after eight interviews. The final sample included a range of firm sizes, audit experience levels, and geographic regions, providing diverse perspectives. Snowball sampling was used to recruit participants, which is suitable for accessing a specialised professional group. The interview guide examined the perceived impact of the declining RA population on audit quality, firm operations, regulatory pressures, talent retention, and the profession’s sustainability. Ethical clearance was obtained, and all participants gave informed consent. Refer to

Section 4 for the Ethical Approval and Informed Consent.

4. Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

The study was conducted following the ethical guidelines of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (26 February 2025–26 February 2026; ref. HSSREC/00008274/2025). Permission to access participants was obtained through formal gatekeeper letters from IRBA and the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA). Participation was voluntary, and all participants gave informed consent at the start of the recorded interviews. No personal identifying information was collected, and all responses were kept strictly confidential.

5. Analysis and Discussion of Results

The South African auditing profession is experiencing a decline in RAs, which threatens the quality and sustainability of assurance services. This chapter analyses data from RAs using semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis with QSR NVivo 12. Zoom interviews were recorded and transcribed, allowing systematic coding to develop themes aligned with the research objectives.

Following

Spencer and Ritchie (

2012) and

Saldaña (

2021), a combination of pre-existing and inductive codes guided the analysis. This approach balanced natural insights with theoretical frameworks, providing a detailed understanding of the decline, its drivers, consequences, and strategic responses from key industry stakeholders.

Table 1 presents the codebook for the thematic analysis. It shows that seven themes were identified from the transcribed data collected from the RAs and are discussed under several subthemes.

6. Theme 1: Sustaining the Auditing Profession Amidst Decline

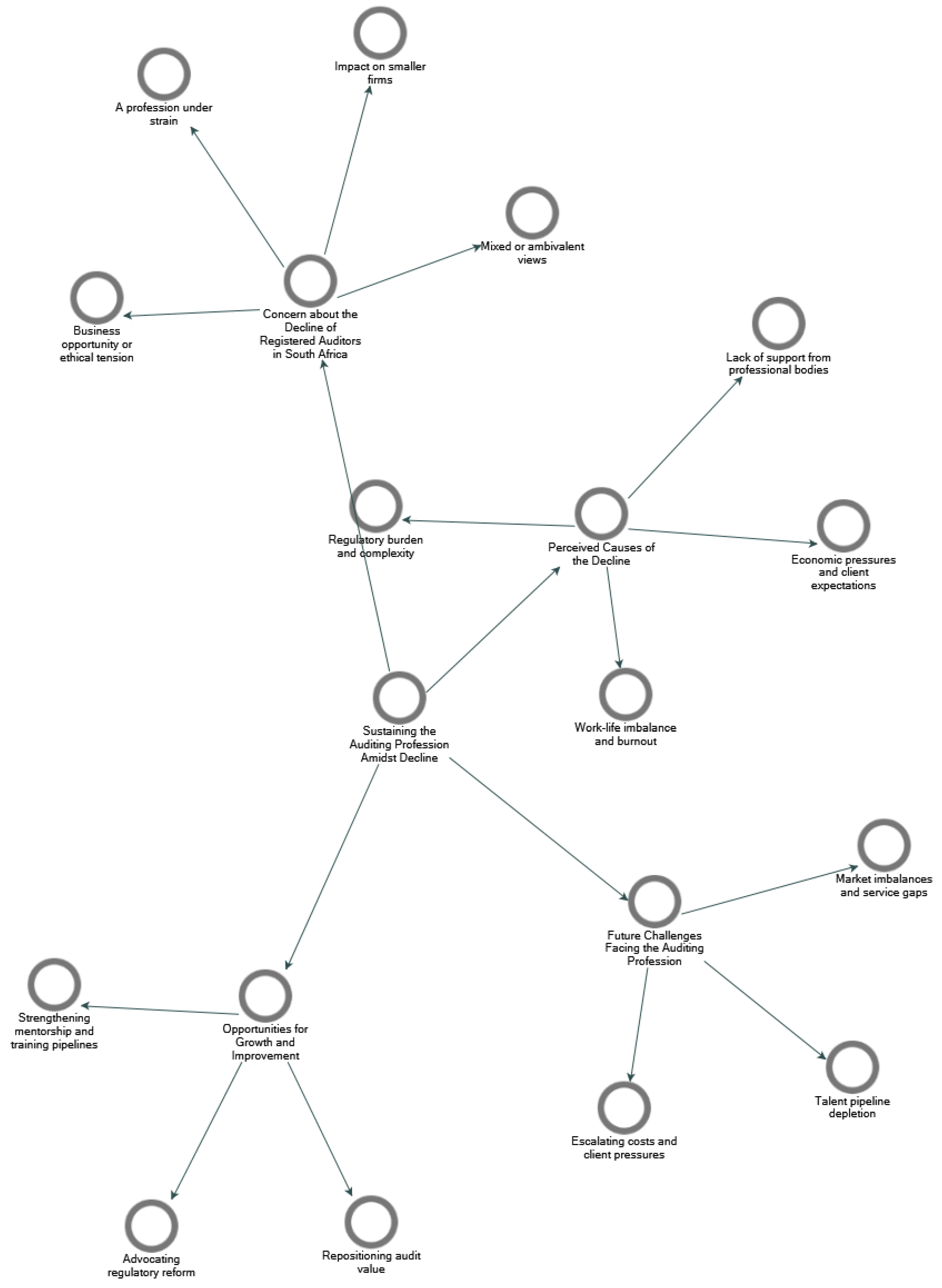

This theme addresses the research aim number 1, which sought to know the concerns about the decline in RAs in South Africa. The theme is discussed under the subthemes depicted in

Figure 1.

6.1. Subtheme 1.1: Concern About the Decline of RAs in South Africa

The decline in the number of Registered Auditors (RAs) in South Africa has prompted a mix of concern, reflection, and pragmatic acceptance among professionals. The interviewees’ perspectives provide a nuanced view, highlighting both the perceived risks and the complexities of the issue.

Many professionals express deep worry about the shrinking pool of RAs, which they believe creates a poor public image and signals broader systemic challenges. As Participant 1 captured, “It doesn’t create a good public sort of image or reputation for auditors. Why are auditors leaving? Clearly, something is broken or something isn’t right… My concern is: what are we as auditors, or what is IRBA, not doing correctly?” This decline is seen as threatening the audit training pipeline, with Participant 3 asking, “If auditing continues in its direction and we give up auditing as something we do, how can we train our future chartered accountants? How would a CA of today be compared with a CA in 20 years if we’ve come through two completely different training mechanisms?” This erosion could impact the quality of future Chartered Accountants (CAs) and the broader ecosystem of accounting expertise. Interviewees also fear reduced protection for stakeholders, with Participant 8 warning, “With a dwindling pool of registered auditors, there’s less protection for stakeholders, which increases risk for businesses and the economy at large”. While some participants noted that the decline could create business opportunities for remaining RAs, this comes with ethical and quality concerns. Participant 4 cautioned, “If RAs are fewer, then it means even the audit fee is going to increase for client organisations. It could be costly both for clients and audit firms themselves”. Smaller firms are particularly affected, struggling to cope with legislative changes, as Participant 1 stated, “It’s much tougher for the smaller firms. All these changes of legislation… it’s making it really difficult for the smaller firms to keep up”. This creates a looming service gap, with Participant 5 noting, “Somewhere there’s going to come a point where we don’t have auditors. The people that will remain won’t be the small or medium practitioners—only the large ones, and they’re not interested in a lot of the smaller clients”. Some views are mixed, with concerns focused on the reasons for the decline, as Participant 2 explained, “I’m more concerned about the reasons for the decline than the decline itself”. Others expressed ambivalence due to a perceived lack of value in the profession, or a conflict between personal marketability and the profession’s long-term sustainability, as Participant 8 admitted, “If I were to be selfish, I’d say no [I’m not concerned] because it means I’m more in demand. But holistically, I am concerned. It points to the sustainability of the profession going forward”. Overall, the decline raises fears about the profession’s reputation, trust, and operational challenges, potentially worsening inequalities and lowering audit quality.

6.2. Subtheme 1.2: Perceived Causes of the Decline

The decline is largely attributed to an onerous regulatory environment, which has expanded in scope and makes it difficult for smaller firms to keep up. Participant 1 lamented, “All these changes of legislation… it’s making it really difficult for smaller firms to keep up. It pushes up training, it pushes up costs”. There is also widespread frustration with a lack of support from professional bodies like IRBA and SAICA, which are perceived as distant and unhelpful. As Participant 1 put it, “I don’t think IRBA and SAICA are as hands-on… they have all these circulars, but they make it your responsibility”. Economic pressures and client expectations also play a role, as clients often seek cheaper audit services and are reluctant to pay for the quality of work involved. Participant 1 reflected, “Clients don’t care about the quality of the audit file. They just want the financial statements signed off, and they don’t want to pay for the work that goes into that”. Finally, work–life imbalance and burnout due to unsustainable workloads are significant contributing factors, with Participant 1 succinctly stating, “The hours that you work is crazy. There’s a lack of work-life balance”.

6.3. Subtheme 1.3: Future Challenges Facing the Auditing Profession

Participants were particularly concerned about talent pipeline depletion. Participant 3 warned, “How can we train future CAs if auditing is no longer part of their foundation? What will the CA of tomorrow look like compared to today’s?”. This will make it challenging to mentor and train future CAs. This will exacerbate market imbalances and service gaps, particularly for smaller clients who may struggle to find auditors. Participant 5 foresaw, “The people that will remain will be large practitioners… and they’re not interested in smaller clients. There’s going to be a huge gap in service delivery”. The imbalance between fewer auditors and consistent client needs is expected to escalate audit costs and competition for services, as Participant 6 pointed out, “There’ll be more clients but fewer auditors. That could drive up costs and create competition among clients just to get audits done”.

6.4. Subtheme 1.4: Opportunities for Growth and Improvement

Despite the concerns, some participants identified pathways for renewal. These include repositioning the value of auditing to clients and society by highlighting its critical role in safeguarding public interest. Participant 8 reflected, “With fewer auditors, there’s less protection for stakeholders. We need to remind people of the critical role we play in safeguarding public interest”. There is also a strong call for regulatory reform to simplify or tailor regulations based on firm size and capacity, especially for smaller firms, as Participant 1 argued, “Smaller firms can’t be held to the same regulatory standard as the big firms without support… It’s just not sustainable”. Furthermore, strengthening mentorship and training pipelines is crucial for nurturing the next generation of auditors. Participant 4 suggested, “We need to ensure there are enough RAs to mentor trainees and guide them properly”.

Without concerted action, the decline of RAs could significantly reshape the assurance landscape, diminishing its capacity to serve South Africa’s public interest. Theme 1 is supported by multiple sources documenting shrinking pipelines and attrition.

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) frame the decline as a global, multifactorial trend, with talent shortages, recruitment challenges, and burnout frequently cited.

Caseware (

2023) reported rising hiring difficulties, firms turning work away, and a shrinking graduate pool. Empirical and interview-based studies, including

Murray (

2024),

Boyle et al. (

2024), and

Jahn and Loy (

2023), focus on falling enrolments and talent scarcity. Research on exits and retention (

Abramova et al. 2025;

Knechel et al. 2021;

Harber 2018) links declining appeal, turnover, and “brain drain” to the auditor decline. Many studies examine competencies, quality, market behaviour, or role changes without measuring numerical decline. Reviews of supply–demand gaps (

Kroon and Do Céu Alves 2023), academic career choices (

Plumlee and Reckers 2014), and entry-level skills (

Pasewark 2021) focus on fit and abilities rather than headcount. Quality-focused oversight (

IRBA 2024b) tracks remediation and deficiencies, not workforce size. Technology-oriented research (

Isotalo 2024) highlights transformations from AI and automation.

The strongest support for Theme 1 comes from the overlap of pipeline contraction (fewer accounting students and graduates choosing audit), negative work perceptions (stress, burnout, alternative career options), and retention challenges (measurable turnover). Neutral or differently focused sources narrow the scope: concerns about competencies, quality inspections, or technological change may affect audit practice and valued skills, but do not directly show a decline in RA numbers. In South Africa, the alignment of local evidence on falling audit appeal with international pipeline and retention data underscores that sustaining the profession requires targeted interventions in attraction, development, and retention, rather than only curriculum or quality control reforms.

7. Theme 2: Reasons for the Decline in Registered Auditors

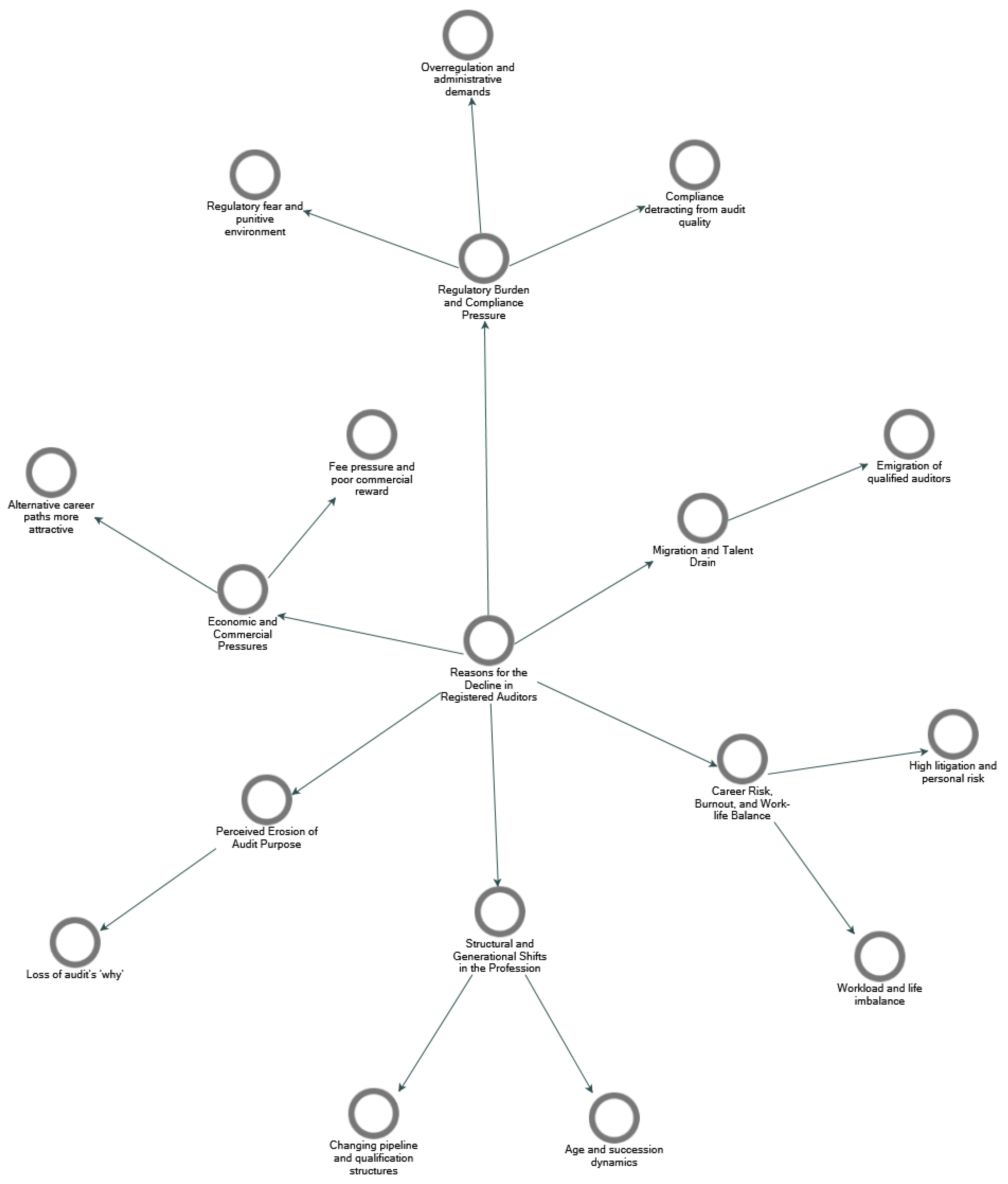

This theme addresses research aim number 2. The number of RAs declined by 11.72% from 2019 to 2023, and the decline of assurance RAs was 3.46% within the same period. Comment on possible reasons for these trends. This section presents an in-depth analysis of interviewees’ perspectives regarding the reasons behind the decline in RAs between 2019 and 2023. The theme is discussed under the subthemes depicted in

Figure 2.

7.1. Subtheme 2.1: Regulatory Burden and Compliance Pressure

Excessive regulation is a primary concern, particularly for smaller firms lacking resources. As Interviewee 2 noted, “Overregulation is definitely a massive part… just the amount of time that we’re spending on stuff that’s not reviewing the files. That’s just out of balance at the moment”. Auditors also feel targeted by regulators, creating a punitive environment and fear of penalties, with Interviewee 5 stating, “you are reminded daily that you will be penalised up to 25 million rand by IRBA… They even use the words ‘we will catch you’”. This intense focus on compliance often detracts from actual audit quality, as Interviewee 8 explained, “We focus so much on ticking the box that you miss the fact that this company has going concern issues… that is what extreme regulation is doing”.

7.2. Subtheme 2.2: Economic and Commercial Pressures

Rising costs, client fee resistance, and declining profitability make auditing commercially challenging. Interviewee 1 highlighted that “The fees that you recover are almost not worth doing the audit work,” and Interviewee 8 described auditing as “a grudge buy… it’s an expense on the income statement that stands out like a sore thumb”. Consequently, alternative career paths, such as computer programming, are increasingly viewed as more attractive due to higher compensation and less regulatory oversight. Interviewee 5 summarised, “Auditing is not sexy anymore”.

7.3. Subtheme 2.3: Migration and Talent Drain

The portability of South African audit qualifications leads to many qualified auditors emigrating to countries like the UK, Europe, or Australia. This means they no longer need to maintain their RA registration in South Africa, contributing to the decline. As Interviewee 4 observed, “Quite a number of people in our industry have migrated to other countries… there won’t be a need to continue registering as an RA with IRBA”.

7.4. Subtheme 2.4: Career Risk, Burnout, and Work–Life Balance

Auditors face high personal litigation and risk, making the profession a “soft target for regulation,” as Interviewee 3 noted, where “those who could run away have, and those that can’t are stuck”. The demanding workload also leads to burnout and a poor work–life balance, especially after COVID-19 shifted perceptions of personal time. Interviewee 2 stated that “The perception is that auditing takes a lot of your personal time. People aren’t as keen for that these days”.

7.5. Subtheme 2.5: Structural and Generational Shifts in the Profession

Older auditors are increasingly stepping away, leaving younger partners to bear the heavy load. Additionally, new qualification hurdles, such as the ADP programme, are seen as discouraging and an “unappealing” “prison sentence” for trainees, contributing to a changing pipeline.

7.6. Subtheme 2.6: Perceived Erosion of Audit Purpose

Many participants feel a declining sense of professional purpose. Interviewee 8 noted, “There’s not a big talk around the purpose of the profession any longer… we need to understand the why of what we are doing”. The profession, once prestigious, is now seen as having lost its appeal.

In conclusion, the decline in RAs stems from a complex interplay of regulatory, economic, generational, and personal factors. If these systemic challenges and changing professional priorities are not addressed, the profession’s long-term sustainability in South Africa is threatened.

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) stated an 11.72% drop in Registered Auditors (2019–2023) by mapping six mutually reinforcing causes. On the talent pipeline and perception, evidence points to both quantity and fit problems: skills–demand gaps are flagged in

Kroon and Do Céu Alves (

2023); firms report recruitment strain and a shrinking graduate pool in

Caseware (

2024); South African appeal is declining for young CA(SA)s in

Harber (

2018); and large-firm perspectives diagnose fewer accounting graduates and readiness concerns in

Murray (

2024).

Regulation and compliance costs alter the profession’s risk–reward profile, perceptions of over-regulation and the chilling effect of rotation are prominent in

Harber (

2018); inspection demands and remediation work are documented in

IRBA (

2024b); quantified cost pressures appear in

Celestin (

2020b); cross-regional failure patterns tied to regulatory stringency are noted in

Celestin (

2020a); and fee-raising structures such as joint audits are discussed in

Coffee (

2019). Talent shortages, recruitment challenges, and burnout are evidenced by firm surveys in

Caseware (

2024), reinforced by outflows from assurance roles in

Harber (

2018), systematic departure drivers in

Knechel et al. (

2021), junior exit rates in

Abramova et al. (

2025), and by the practitioner perceptions captured in

Murray (

2024).

Technological change adds to skills mismatches and transition costs: firms face challenges with virtual work, BI tools, and adoption hurdles (

Caseware 2023); AI’s effects on audit roles are explored in

Isotalo (

2024); and competency misalignment with evolving skill needs is noted in

Kroon and Do Céu Alves (

2023). Financial pressures and profitability influence incentives and strategy: consulting–audit income dynamics and fee economics are discussed in

Coffee (

2019), fee payments and bargaining power in

Kharuddin and Basioudis (

2022), wage-related attractiveness in

Albu et al. (

2011), and profitability concerns in

Murray (

2024). Audit resignations and risk factors are evidenced by departure hazards (

Knechel et al. 2021), South African turnover dynamics (

Harber 2018), junior turnover pressures (

Abramova et al. 2025), quality deficiencies (

IRBA 2024b), systemic failure risks (

Coffee 2019), and direct acknowledgement (

Murray 2024). Together, these sources show a decline driven by interconnected pipeline, regulatory, technological, economic, and risk factors, requiring coordinated responses in attraction, development, and retention.

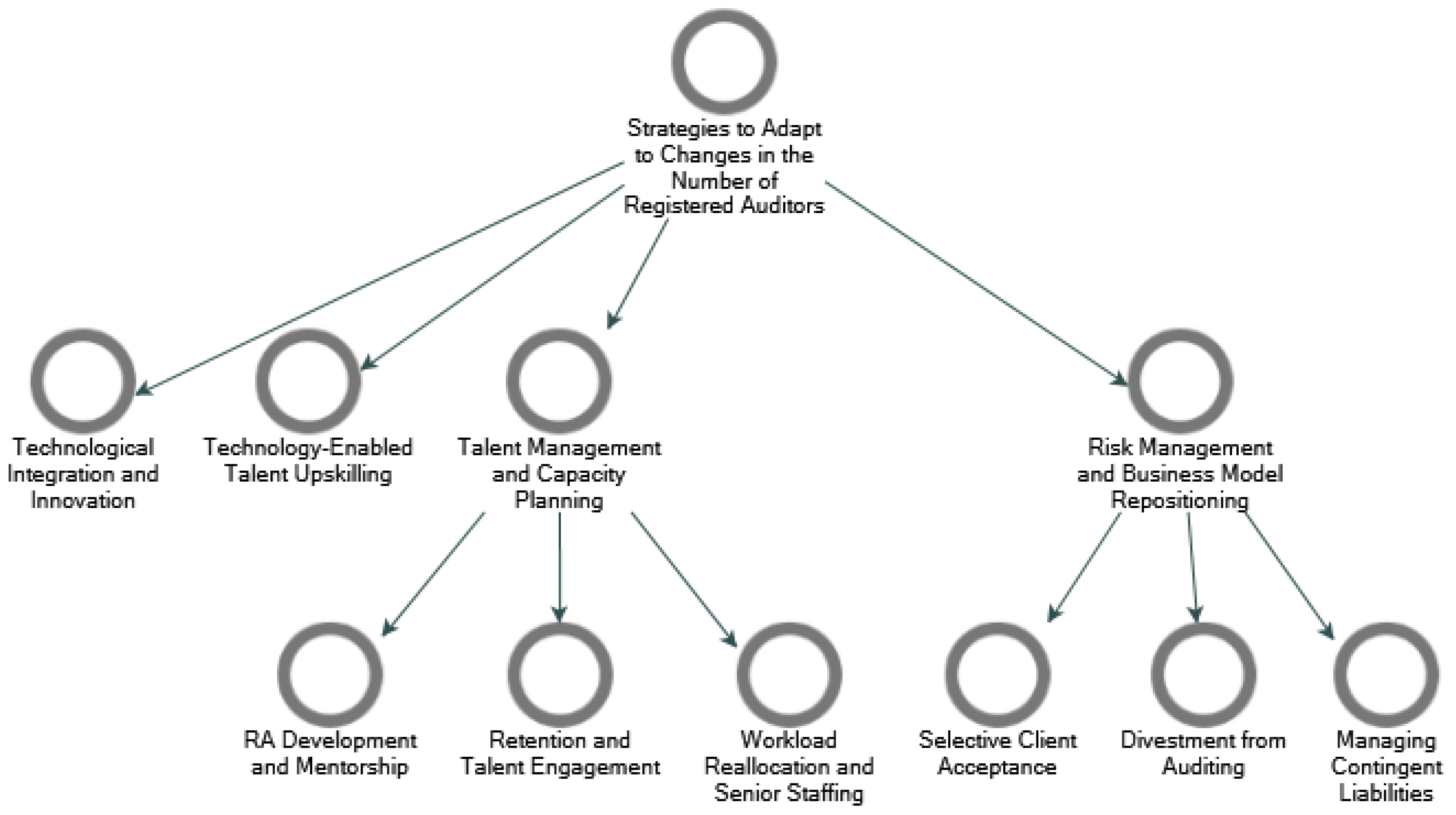

8. Theme 3: Strategies to Adapt to Changes in the Number of Registered Auditors

This theme addresses research aim number 3, which sought to know the strategies the firm implemented to adapt to changes in the number of Registered Auditors. The interviews revealed diverse, multifaceted strategies employed by audit firms to navigate the evolving environment of Registered Auditors (RAs). These strategies were clustered into four major subthemes: (1) Technological Integration and Innovation, (2) Technology-Enabled Talent Upskilling, (3) Talent Management and Capacity Planning, and (4) Risk Management and Business Model Repositioning (

Figure 3).

8.1. Subtheme 3.1: Technological Integration and Innovation

Firms are increasingly adopting Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools and digital platforms to reshape audit processes and enhance efficiency. This helps them navigate the shrinking RA pool and maintain profitability and audit quality. As Participant 8 noted, “The tools are so important… they run a script and basically test 100% of the population… That process probably takes them about a day or two, where ordinarily it would have taken a trainee probably two weeks”. Tools like ChatGPT and Copilot are transforming file preparation and risk assessments, making technology vital for the future of auditing, especially with staffing challenges.

8.2. Subtheme 3.2: Technology-Enabled Talent Upskilling

To address the RA shortage and advanced audit technologies, firms are proactively enhancing their workforce’s digital literacy and technical skills. Participant 8 highlighted this with the establishment of an internal “data school now… we basically train them on all of these things… coding aspects, the tools which they use”. This indicates a shift towards proficiency in coding, automation, and data analysis alongside traditional financial reporting knowledge.

8.3. Subtheme 3.3: Talent Management and Capacity Planning

Firms are prioritising RA development, retention, and adaptive resourcing models.

8.3.1. RA Development and Mentorship

Strategies include structured mentorship via IRBA’s Audit Development Programme (ADP) and diversifying qualification pathways, such as ACCA accreditation, to expand the talent pool. Participant 2 stated, “We provide them with the opportunity to do the IRBA mentorship… and we’ve recently registered with ACCA… we’ve got two ACCA trainees currently at our firm”.

8.3.2. Retention and Talent Engagement

Firms are moving towards co-ownership models and internal promotion to build loyalty and retain experienced professionals. Participant 4 emphasised, “You have to come up with retention strategies… giving people partnership into the firm… make them realise that this firm is not… I’m not working for a particular person. This is mine”.

8.3.3. Workload Reallocation and Senior Staffing

Audit responsibilities are being redistributed, with firms hiring experienced non-RA professionals to perform audit work, allowing RAs to focus on review and sign-off tasks. As Participant 6 mentioned, “We may need to employ more senior staff, who are not necessarily RAs, but that will actually make sure that they do the work, then the RA will just have to review and ensure everything is done accordingly”.

The findings under this theme highlight a key evolution in how audit firms manage human capital. By broadening qualification pathways, offering participatory career paths, and reorganising task assignments, firms are moving toward a more agile and inclusive resourcing strategy. These interventions address not only the symptoms of the RA shortage but also structural causes, such as rigid qualification routes, talent loss, and limited career growth. Moreover, these strategies show a sector balancing regulatory compliance, economic sustainability, and human-centred leadership. The focus on empowerment, mentorship, and collaborative staffing indicates that the South African auditing profession is not just reacting to a crisis, but reimagining its workforce to succeed in a complex, evolving environment.

8.4. Subtheme 3.4: Risk Management and Business Model Repositioning

The structural decline in the number of Registered Auditors (RAs) in South Africa has led audit firms to critically reassess their business models and risk exposure. As financial, regulatory, and operational pressures increase, firms are engaging in strategic repositioning, focusing on profitability, selectivity, and liability mitigation. The findings show that risk-aware decision-making has become central to sustaining audit practices, as firms contend with high compliance burdens, low audit returns, and rising liability exposure.

8.4.1. Selective Client Acceptance

Many firms are implementing minimum audit fee thresholds and rejecting financially unviable engagements to protect margins and manage regulatory exposure. Participant 2 explained, “We’ve pretty much put a minimum audit fee that we are able to service that client… you’re not able to perform an audit at a profitable margin”.

8.4.2. Divestment from Auditing

Some firms are even exiting assurance services altogether, shifting focus to more profitable areas like tax advisory and consulting, to reduce compliance burdens and professional indemnity risks. Participant 5, for instance, expressed intent to “de-register as a registered auditor by the end of next year… I will make up 50% more of that fees by having more time to attend to my non-audit clients”.

8.4.3. Managing Contingent Liabilities

There is significant concern over the disproportionate risk–reward dynamics, where small profits are easily outweighed by potential regulatory fines. Participant 3 highlighted this, noting, “Out of a 6 million Rand audit turnover, we’ve made 190,000 Rand of profit… that profit alone will not cover one fine from IRBA”. The perceived lack of appeal mechanisms further exacerbates these fears.

These strategies demonstrate a significant evolution in how South African audit firms are navigating a high-risk, low-reward environment, moving towards more agile and inclusive resourcing models to ensure resilience and ethical sustainability.

Theme 3 shows firms adapting to a high-risk, low-reward environment through four complementary levers: (1) Technological Integration and Innovation, (2) Technology-Enabled Talent Upskilling, (3) Talent Management and Capacity Planning, and (4) Risk Management and Business Model Repositioning. For technological integration and talent upskilling, adoption is progressing but uneven.

Caseware (

2023) notes that “cloud adoption keeps rising” and “business intelligence catches on,” while also pointing to operational frictions in “using new technologies” and “communicating with clients virtually.”

Caseware (

2024) extends this to “virtual-world realities,” talent responses, and new services. At the profession level, emerging tools amplify the shift, as

Isotalo (

2024) explains how AI, automation, and blockchain are reshaping evidence gathering and judgment, highlighting the need for clarity on which audit tasks are being displaced.

For talent management and capacity planning, the evidence aligns with

Caseware (

2023), which flags “talent management a top challenge,” noting difficulty in “finding the right talent” and lagging skills readiness. The upstream pipeline is under pressure, as

Boyle et al. (

2024) highlight declining enrolments, negative perceptions, and faculty hiring issues;

Murray (

2024) similarly cites a “lack of accounting professionals” and falling enrolments. Competency gaps remain, with

Kroon and Do Céu Alves (

2023) suggesting curriculum recalibration for future RA capacity, while

Jahn and Loy (

2023) notes that strict access requirements (e.g., partial exams) increase workload and stress for entrants. Retention is as important as acquisition, as

Abramova et al. (

2025) reference “Retention Effectiveness Strategies for CPA Firms,” emphasising the need to stabilise headcount, not just fill the pipeline.

Strategic triage pruning client portfolios, exiting certain audits, and mitigating liability stems from pressures documented across sources.

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) link firm behaviour to financial pressure and profitability, audit resignations and risk factors, and regulation and compliance costs, situating choices within institutional constraints. Liability exposure is evident in

Sanni (

2024), which discusses negligent cases affecting large firms (e.g., Deloitte), reinforcing proactive risk management. Regulatory intensity and recurring deficiencies, according to

IRBA (

2024b), increase the cost of engagement (e.g., revenue recognition, journal entries, significant judgments/estimates), encouraging portfolio focus. Market structure and specialisation choices, per

Kharuddin and Basioudis (

2022), provide the economic rationale for fee payments, economies of scale, and selective industry focus behind narrowing to defensible niches. Together, these sources show firms investing in technology, rebuilding capacity, and tightening risk perimeters as practical responses to the sustained decline in RAs and broader constraints on South African audit practices.

9. Theme 4: Regulatory Challenges in the Audit Profession

This theme addresses research aim number 4, which highlights the challenges posed by current audit regulations in South Africa. The narratives reveal that auditors face significant difficulties arising from regulatory frameworks that many view as disproportionate, punitive, and out of touch with the realities of practice. Three overarching subthemes emerged from the data, as illustrated in

Figure 4 below:

9.1. Subtheme 4.1: One-Size-Fits-All Regulation and the Disproportionate Burden on Auditors

Auditors are deeply frustrated by rigid regulations that fail to account for differences in client size, complexity, and risk. This “one-size-fits-all” approach leads to inefficient, costly procedures for smaller entities, without improving audit quality. For instance, Interviewee 1 highlighted, “Now you have to audit a sole proprietor or director… and you have to do the audit procedures as if you’re doing it for a company that’s doing 100 million revenue…”. This lack of differentiation, despite proposals for less complex entities, places an undue burden on firms. Furthermore, an “overemphasis on documentation” creates a “tick-box” culture where auditors are so focused on completeness that they “miss the bigger picture because they’re under so much pressure” (Participant 8).

9.2. Subtheme 4.2: The Weight of Compliance

The audit profession faces immense pressure from harsh penalties and an unsustainable economic model. Excessive fines are viewed as an “existential threat” to smaller firms, with Interviewee 4 stating, “Once you are fined, then you are out of business because it’s beyond hefty”. Even administrative errors can lead to ruinous consequences. This risk leads to an unsustainable “risk-reward imbalance”, where high personal and professional risk is not met with corresponding financial returns, as Interviewee 7 noted: “Auditors take risk by taking on this work… but then you must look at the reward. The rewards are not there. It just doesn’t make sense”. Some auditors even fear losing all their assets due to regulatory actions.

9.3. Subtheme 4.3: Disconnect Between Regulators and Practitioners

There is a widespread feeling that regulators provide “little practical support”, focusing on theory and legislation rather than offering guidance or solutions. This creates a relationship defined more by fear than collaboration. Many participants believe that regulators lack “real-world audit experience”, leading to unrealistic expectations and an “ineffective oversight”. Interviewee 3 strongly critiqued this, saying, “There’s a disconnect. If they don’t sit in our firm, they don’t understand where we come from. That gap is something that needs significant attention”. Ironically, this regulatory overreach, intended to improve audit quality, is feared to “undermine it” by diverting time and resources from substantive audit work to mere compliance with form and checklists.

In essence, auditors feel they are “struggling under the weight of disproportionate and rigid regulation”. They advocate for a more nuanced, risk-based, and supportive regulatory approach that acknowledges the realities of practice, especially for smaller firms, to ensure the long-term quality and integrity of the audit profession.

Theme 4, that auditors perceive regulation as disproportionate, punitive, and disconnected, is supported by multiple sources.

Harber (

2018) explicitly confirms this, describing South Africa’s profession as over-regulated, with burdens increasing work and costs, warning that measures like MAFR will further reduce the profession’s appeal. The scoping review by

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) reinforces this with “regulatory fatigue” and rising demands, framed as coercive and normative pressures in institutional theory. Practice-side sentiment aligns with

Caseware (

2023), which lists “new laws and regulations” among the top challenges, showing daily operational strain. Legal pressures appear in

Sanni (

2024) (e.g., negligent cases against Deloitte in China; ASIC proceedings),

Ghosh and Tang (

2015), which links litigation risk scores to enforcement actions, and

Albu et al. (

2011), which connects rule-based changes to reduced comparability. Structural frictions are noted in

Jahn and Loy (

2023), linking higher access requirements to fewer professionals and highlighting that small practices face oversight and sanctions more often. Market economics and professional expectations intersect in

Coffee (

2019), which describes auditing as a low-margin “commodity” that pushes talent to consulting and questions whether legislative fixes suffice, and in

Kharuddin and Basioudis (

2022), where regulatory demands for deep industry knowledge raise engagement complexity. Overall, the evidence supports Theme 4’s claim that regulations and related legal exposures are widely seen as costly, demanding, and misaligned with professional realities, even as some sources only document effects rather than judging proportionality.

10. Theme 5: Challenges Facing the Auditing Profession in the Next 5 to 10 Years

This theme addresses research aim number 5. The interviews revealed a complex landscape of challenges facing the South African auditing profession. The findings are organised into four overarching subthemes, illustrated in

Figure 5 below.

10.1. Subtheme 5.1: A Shrinking, Pressured Profession

The profession faces an auditor exodus and critical talent shortages. Interviewee 6 predicted, “I see a huge decrease in this part as well… The assurance category within the RAs will carry on decreasing even higher”. This will lead to a “significant gap between the demand and the supply”, meaning “There will not be enough auditors to conduct the audit requirements of the commercial sector” (Participant 3). Attracting and retaining talent is difficult due to better opportunities abroad or with international firms, leading to existing resources becoming “fatigued, drained… risk of losing quality staff essentially” (Participant 8).

10.2. Subtheme 5.2: The Risk–Reward Imbalance and Economic Pressures

The profession is seen as increasingly punitive, with high personal and professional risk not matched by sufficient financial returns. Interviewee 7 warned, “The risk versus the rewards, that is the big issue to say if those dynamics don’t change, then I think the profession… is doomed”. Regulatory bodies, like IRBA, are perceived to “name and shame,” with “one error, you become… so bad” (Participant 6), further eroding appeal. Rising audit fees, driven by regulatory and operational pressures, risk pricing clients out of the market, causing them to “prefer a cheaper service… They might just move over to an independent review, which is substantially cheaper” (Participant 2).

10.3. Subtheme 5.3: Technological Disruption and Readiness

Technology is both a crucial tool and a threat. Firms that fail to adapt “run the risk of becoming obsolete” (Participant 8). However, there are questions about the relevance of current audit practices in a digital future, and clients, especially smaller ones, may not be ready for tech-enabled audits, as “AI will never be able to test the system if the accountant is doing something different every month” (Participant 5).

10.4. Subtheme 5.4: Systemic Weakness in Oversight and Policy

Participants expressed frustration with regulatory fragmentation and a perceived lack of support from IRBA. Interviewee 3 suggested that “IRBA must split, one division to support auditors, another to regulate them”. Additionally, outdated Public Interest Score thresholds, in place since 2008, are forcing “More and more clients are just being scoped into audits because the public interest score hasn’t been adjusted” (Interviewee 8), adding to the burden.

In summary, the auditing profession faces a “perfect storm” of talent shortages, economic pressures, regulatory overreach, and technological disruption. Unaddressed, these issues could lead to “bigger accounting scandals… not because the auditors aren’t doing their job, [but] because they simply don’t have the time, because there aren’t enough of them” (Participant 3), threatening the long-term quality and integrity of the audit industry.

Theme 5 has direct evidence from

Caseware (

2023), which identifies “talent management” as a top challenge, cites a shrinking graduate pipeline, and notes retention difficulties. Empirical work by

Knechel et al. (

2021) documents departure and turnover hazards among auditors, while

Harber (

2018) reports a South African decline in the appeal of remaining in audit, with movement out of assurance roles.

Abramova et al. (

2025) highlights staffing pressures and the need for retention strategies. Broad scoping in

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) links pipeline weaknesses, recruitment challenges (including burnout), and resignation risks to the global contraction.

Pasewark (

2021) adds that business schools struggle to equip entrants with needed competencies, reinforcing the supply problem.

Murray (

2024) directly lists shortages, falling enrolments, and firm responses (pay, flexibility, outsourcing, upskilling, and investment in AI/technology). Several studies indirectly support a picture of a pressured profession.

Kroon and Do Céu Alves (

2023) show persistent competency gaps between universities and market expectations, sustaining shortages in “job-ready” talent. Regulatory demands and failure dynamics (

Celestin 2020a), legal exposure (

Sanni 2024), and risk metrics (

Ghosh and Tang 2015) point to heightened practice risk and cost. Shifting skill requirements and “hybridisation” pressures appear in

Albu et al. (

2011), enrolment constraints in

Boyle et al. (

2024), and academic pipeline frictions in

Plumlee and Reckers (

2014). Continual remediation needs in

IRBA (

2024b) underline resource pressure; broader trust, regulatory proposals, and fee-market stresses (

Coffee 2019), and competitive or specialisation dynamics (

Kharuddin and Basioudis 2022) further describe the environment. Technology-driven transformation and task displacement risks (

Isotalo 2024) and market concentration or client-switching pressures (

Mattar et al. 2024) also reinforce a narrative of sustained pressure.

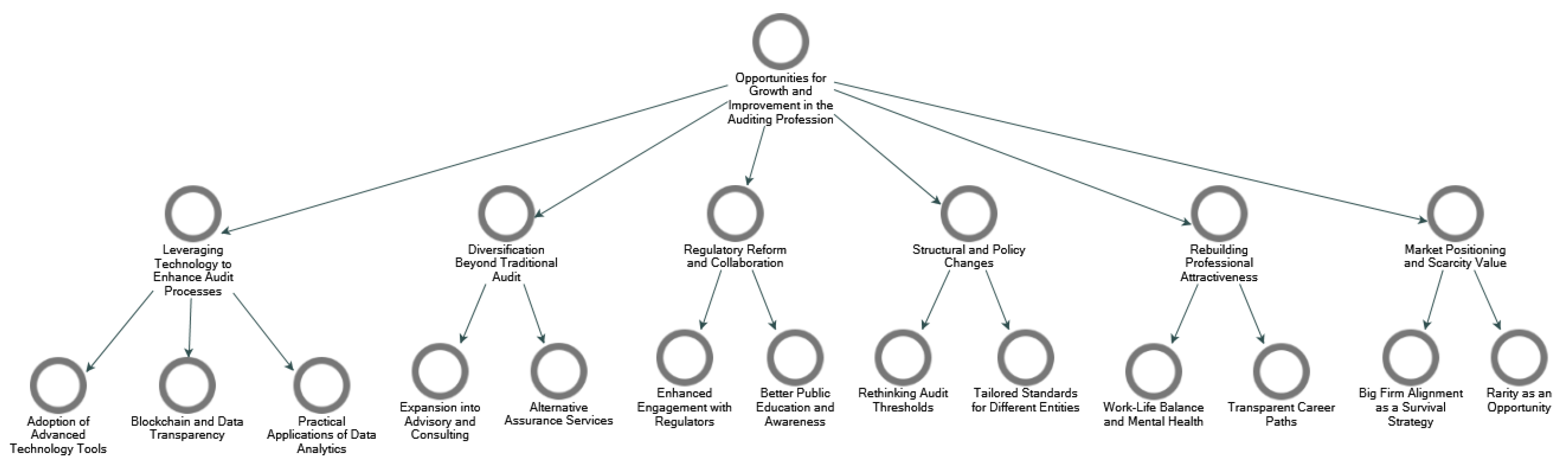

11. Theme 6: Opportunities for Growth and Improvement in the Auditing Profession

This theme addresses research aim number 6, which explores the opportunities for growth and improvement in the auditing profession. The transcribed data revealed several intertwined opportunities for growth and improvement in the auditing profession. These opportunities reflect both structural and human elements of the profession and draw from the lived experiences of the interviewees.

Figure 6 illustrates subthemes and categories uncovered from the transcript.

11.1. Subtheme 6.1: Leveraging Technology to Enhance Audit Processes

Participants view technology as crucial for improving audit efficiency, accuracy, and value. This includes adopting advanced tools, exploring blockchain for data transparency, and using data analytics for exception reporting. As Participant 1 noted, “Opportunities exist for auditors by utilising advanced technology tools… on seeing your procedures, on seeing the audit experience with using these tools”. There is potential for immediate benefits, as Participant 3 illustrated: “In Xero you can run an exception report… pull out any journal that was passed between 11 p.m. and 3 a.m. Now, those must help”.

11.2. Subtheme 6.2: Diversification Beyond Traditional Audit

There is a strong belief that firms must diversify their services beyond traditional audits to remain relevant and grow. This includes expanding into advisory, forensic, and business consulting services, which large firms are already doing. Participant 4 observed, “If you have seen the bigger firms, they’ve done this already… income is coming from advisory, forensic audit, business planning… HR functions. Opportunities are around consulting rather than your normal auditing”. There is also a need for alternative assurance services tailored for smaller entities, with a missed opportunity cited regarding standards for less complex entities.

11.3. Subtheme 6.3: Regulatory Reform and Collaboration

Interviewees called for improved, more meaningful collaboration between audit firms and regulatory bodies like IRBA. Participant 2 found it “really nice to have IRBA visit us… we could sit around the table, provide input”. There is also a need for better public education and awareness about the auditor’s role, especially regarding fraud detection and the sample-based nature of audits, to manage expectations. Participant 3 suggested, “Better education to the public about what an auditor entails, especially around a sample type basis… remove the pressure that everything they see is absolute”.

11.4. Subtheme 6.4: Structural and Policy Changes

The profession needs to rethink audit thresholds and standards, particularly for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs), which are currently subject to the same stringent rules as large corporations. Participant 7 critiqued the current Public Interest Score (PIS) threshold, stating, “350 PIS is a lot actually… until 350 there’s no requirement to be audited. That is a lot of work lost… this profession in South Africa must just disappear; it’s going extinct because of these things”. Participant 3 questioned, “How is it that ABC Trading down the road needs to comply with the same standards as Sasol? How is it possible those two coexist and have to sing from the same hymn sheet?”

11.5. Subtheme 6.5: Rebuilding Professional Attractiveness

To attract and retain talent, the profession must address its demanding nature and promote a better work–life balance and mental health support. Participant 1 admitted, “You can’t even offer them work-life balance because inherently the audit environment… there is no work-life balance”. Additionally, transparent career paths and clear communication about progression and rewards are vital to cultivate growth, especially for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

11.6. Subtheme 6.6: Market Positioning and Scarcity Value

There are mixed views on market positioning. Some participants suggest that future RAs should align with bigger firms for survival, as they have the resources to defend themselves. Participant 6 advised, “Future RAs… better be ready to align themselves to big firms that already have facilities and even legal services to defend the companies”. Conversely, others see the declining number of RAs as an opportunity, creating scarcity value for those who remain. Participant 2 commented, “A decline in registered auditors is a concern… but for someone that’s already a registered auditor, that also provides opportunity because it distinguishes myself from someone else”.

In essence, the auditing profession must modernise, humanise, and refocus on delivering value by embracing technology, diversifying services, advocating for regulatory reform, and improving its appeal to ensure long-term sustainability and quality.

Multiple studies highlight the burden side of the ledger.

Celestin (

2020b) reports a 25% rise in audit hours post-change, showing heavier processes and resource strain;

Harber (

2018) describes the South African audit as over-regulated; and the scoping review by

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) identifies rising regulatory demands, regulatory burden, and coercive pressures. Together, they support structural recalibration (including thresholds) as a way to restore sustainable work volumes. Market Positioning and Scarcity Value points to two linked strategies. First, big-firm alignment:

Celestin (

2020b) notes larger firms absorb adoption costs more easily;

Kharuddin and Basioudis (

2022) find markets perceive higher quality from large or industry-specialist auditors;

Isotalo (

2024) reflects the Big Four’s gravitational pull; and

Mattar et al. (

2024) documents Big Four dominance as complex clients seek control through them. This supports the interview view that future RAs gain resilience by aligning with scale, infrastructure, and legal capacity. Second, scarcity as opportunity: persistent shortages and exits increase the value of remaining RAs.

Caseware (

2023) reports difficulty finding and retaining qualified talent and a shrinking graduate pipeline;

Knechel et al. (

2021) examines departures and turnover;

Dawkins (

2023) flags declining enrolments;

Jahn and Loy (

2023) links higher access requirements to tougher entry;

Harber (

2018) shows young CA(SA)s avoiding audit;

Plumlee and Reckers (

2014) highlights student perception effects;

Abramova et al. (

2025) notes retention strategies;

Pasewark (

2021) details curriculum gaps;

Murray (

2024) lists firm responses (pay, flexibility, outsourcing, upskilling, AI/tech);

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) synthesises shortages, burnout, and attrition; and

Ghosh and Tang (

2015) adds evidence on auditor resignations. The net effect is that regulatory load and talent scarcity compress supply while increasing the relative market power, pricing, and selection options of those who remain.

12. Theme 7: Strategies for Sustaining the Assurance Industry Amidst a Decline in Registered Auditors

This theme addresses research aim number 7. The sustained decline in the number of Registered Auditors (RAs) in South Africa presents a pressing challenge to the integrity and viability of the national assurance industry. Interviews with professionals across the audit sector revealed a deep-seated concern for the future of the profession, along with a range of strategies aimed at mitigating the decline. Their insights, grounded in lived experience, suggest that survival and rejuvenation of the audit sector require a multi-pronged and collaborative approach. Five interrelated subthemes emerged: regulator reforms, technological innovation, professional collaboration, talent development and retention, and legislative and policy engagement (

Figure 7). Collectively, these strategies point toward a vision of systemic renewal built upon reform, inclusion, and innovation.

12.1. Subtheme 7.1: Regulator Reforms

A critical need for reform in the audit regulatory environment, particularly regarding IRBA’s role, was highlighted. Participants advocated for more practical support and guidance, such as interactive, scenario-based training, and criticised the excessive red tape and slow processes for RA registration and proficiency interviews. Interviewee 8 stated, “It was such a lengthy process to register as an RA… If I wasn’t passionate… there’d be no reason for me to jump through all those hoops”. There was a strong call to shift the regulatory culture from punitive to supportive, with Interviewee 3 questioning the fear-driven environment: “Who wants to drive to work every day to sign off on a job that could cost you your house, your family, your marriage?”. Reforms to the ADP and other entry barriers were also suggested, with some advocating for automatic RA registration post-articles, as “This 18-month ADP doesn’t work… Becoming a CA is already seven years. Very few people are keen to do extra 18 months” (Participant 6).

12.2. Subtheme 7.2: Technology and Innovation

Technology is seen as a crucial lever to sustain the profession, especially in light of declining human capital. Greater adoption of AI, automation, and smart audit tools could offset staff shortages, reduce fatigue, and improve efficiency. As Interviewee 1 explained, “We need to rely more on software and technology and artificial intelligence… helpful in terms of cutting off time… and the quality”.

12.3. Subtheme 7.3: Collaboration and Networks

Inter-firm collaboration, especially among small and medium-sized firms, was identified as a key strategy to pool resources, share best practices, and co-create cost-effective methodologies. Interviewee 1 recommended that firms “Join up in associations or networks… for training, discussion forums… create audit procedures or standards together”. Fostering a stronger sense of community and belonging among auditors, particularly younger professionals, through events and networking was also deemed essential to improve morale and professional identity.

12.4. Subtheme 7.4: Talent Development and Retention

Developing the talent pipeline is both a long-term investment and a short-term necessity, requiring grassroots awareness campaigns at high school and university levels. Mentorship and relationship-building with students were also highlighted. However, socio-economic barriers such as low compensation, ‘black tax’, and delayed financial returns deter graduates. Interviewee 8 emphasised, “They don’t factor that people don’t have time… they want to accumulate wealth for their family… black tax is integrated into so many underprivileged households… They must be alive to these things”. Furthermore, macroeconomic instability and governance challenges contribute to the brain drain, as Interviewee 4 observed, “When there was ridiculous load shedding… that’s when most people left for overseas… government must ensure the economy is functioning well”.

12.5. Subtheme 7.5: Legislative and Policy Engagement

Participants called for a legislative and policy review to redefine audit obligations, questioning whether all entities currently require statutory audits to reduce unnecessary burdens. Interviewee 5 asked provocatively, “Do we really have to audit all these things?... Isn’t there another way the auditing profession can assist to achieve your goals?”. Lastly, public education campaigns are needed to clarify the scope and limits of audit work, with Interviewee 5 suggesting, “IRBA… tell the public what an auditor does and doesn’t do?” to manage unrealistic expectations and restore trust.

These strategies collectively point towards a systemic renewal based on reform, inclusion, and innovation to ensure the long-term viability and integrity of the South African assurance industry. Theme 7 (regulatory reforms, technological innovation, professional collaboration, talent development/retention, and legislative/policy engagement) is broadly supported, though several sources highlight execution risks. On regulatory reforms,

IRBA (

2024b) shows positive movement (fewer referrals; more “some improvement” outcomes), while

Celestin (

2020b,

2020a) illustrates how new regimes and proactive interventions shape practice. Guidance stressing industry understanding (

Kharuddin and Basioudis 2022) and varied EU entry rules (

Jahn and Loy 2023) show policy levers affecting quality and access. At the same time,

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) caution that regulatory burden and fatigue can worsen declines, and

Coffee (

2019) questions whether rule changes alone restore trust—useful caveats for reform design. On technological innovation, both uptake and strain are evident. Firms report accelerating cloud/analytics adoption and operational friction (

Caseware 2023), while inspections point to recurring IT-control weaknesses and the need for better tech integration (

IRBA 2024b). The scoping review recognises technology’s disruptive force (

Abrahams and Phesa 2025), and

Isotalo (

2024) details AI’s impact on evidence and judgment. Yet practical priorities differ:

Murray (

2024) finds firms rely more on outsourcing and temporary staff than tech investment to fill gaps, suggesting innovation is necessary but not always a first-line fix. Professional collaboration and talent development/retention are interlinked.

Kroon and Do Céu Alves (

2023) emphasise professional bodies and education regulators aligning competencies;

Boyle et al. (

2024) show active dialogue via advisory councils and conferences;

Coffee (

2019) encourages investor–auditor engagement (e.g., Q&A). On talent, the consensus is clear:

Caseware (

2023) documents difficulties finding and retaining staff;

Dawkins (

2023) reports declining enrolments; firms respond with pay, flexibility, upskilling, and AI/tech investment (

Murray 2024). Retention is clarified by

Knechel et al. (

2021) and

Abramova et al. (

2025), while

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025) connect pipeline strain, burnout, and attrition. Still,

Kroon and Do Céu Alves (

2023) note persistent gaps between university output and market competency, signalling ongoing work for educators and accrediting bodies.

Finally, legislative and policy engagement cuts across all pillars, such as

Kroon and Do Céu Alves (

2023), national entry requirements,

Jahn and Loy (

2023), and standard-setting/adoption dynamics,

Celestin (

2020b), show how law and policy steer supply, capability, and practice behaviour. The institutional framing in

Abrahams and Phesa (

2025), coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures, usefully explain why reforms, collaboration, and technology must be coordinated to avoid shifting burdens without solving root causes. In short, the sources back Theme 7’s strategic directions, while underscoring that success hinges on calibrating regulatory load, executing technology well, closing competency gaps, and sustaining targeted retention efforts.

The eight interviewees’ reflections converge on a key insight: sustaining South Africa’s assurance sector requires multi-stakeholder collaboration, structural reforms, and cultural change. These strategies, from regulatory updates and technology adoption to talent development and legislative adjustments, go beyond survival tactics, reflecting a shared vision of renewal. Despite frustrations with bureaucratic delays, strict oversight, and socio-economic disparities, participants also identified opportunities for hope and progress. Their accounts combine critique with practical suggestions, showing that while challenges for the audit profession are significant, they are not impossible to overcome.

13. Policy Implementations

The findings highlight several areas where policy adjustments may help to alleviate the auditor shortage and its wider consequences in South Africa.

13.1. Regulatory Proportionality

Current regulatory requirements, while designed to safeguard quality, appear to have unintended consequences for smaller audit firms, contributing to market exits and reduced competition. Policymakers could consider a more proportional regulatory framework, one that recognises differences in firm size and resources, so as to maintain standards without imposing undue burdens that shrink the audit supply base.

13.2. Education and Training Pipelines

The shortage of qualified auditors is connected to limitations in the training and qualification process. Increasing bursary schemes, encouraging universities to widen access, and simplifying qualification pathways could expand the pool of entrants. Professional bodies and government could also consider cross-border recognition of qualifications to address immediate shortfalls. Remove the ADP and revert to its previous state, where CA(SA)s could automatically register as RAs.

13.3. Market Structure and Competition

With smaller firms exiting, the audit market risks becoming more concentrated, leading to higher costs for clients and potential threats to independence. Policy interventions might include measures to support mid-tier firms, encourage joint audits, or regulate against over-reliance on the Big Four.

13.4. Audit Quality Safeguards

Respondents indicated concern that auditor shortages may undermine audit quality. Regulators could respond by setting guidance on manageable workloads, promoting investment in audit technologies, and closely monitoring quality indicators during periods of workforce strain.

13.5. Forward-Looking Resilience

The profession itself anticipates continuing pressures, suggesting the need for policy that is adaptive and anticipatory. This could involve scenario planning by regulators, professional bodies, and government, with a focus on workforce planning, automation, and cross-jurisdictional cooperation.

14. Conclusions

The study aimed to evaluate the decline of RAs and its impact on the future of the assurance industry in South Africa. The main research question was: How will the decline in RAs affect the assurance industry in the future within the South African economy? The study sought to describe professional concerns about the RA decline, explain the drivers of this decline between 2019 and 2023, document firm-level strategies adopted to adapt to changes in RA numbers, examine regulatory challenges shaping audit practice and their perceived proportionality, assess near-term risks (5–10 years) for capacity, quality, and market structure, identify opportunities for growth and improvement in the profession, and examine strategies to sustain RAs amid the decline. The findings draw on behavioural theory and institutional theory, which unpack the multifaceted realities surrounding RA decline in South Africa, using rich qualitative data to highlight both proximate and structural factors contributing to the trend. Participants described a complex interplay of regulatory pressures, unattractive career incentives, talent migration, and profitability challenges that together reduce the appeal and feasibility of maintaining RA status. The findings highlight that the issue goes beyond individual choices and is deeply rooted in systemic inefficiencies and institutional disincentives.

Notably, audit firms are not passive observers of this decline. They actively engage in talent development through mentorship, alternative qualification pathways, and internal training programmes that strengthen technological capacity. At the same time, firms are repositioning their business models, selectively accepting clients, divesting from audit services, and reallocating workloads to manage risk and maintain financial viability. These strategic shifts reflect a broader transformation of the profession, where sustainability increasingly depends on adaptability, innovation, and stakeholder engagement. The research offers several insights with implications for policy and practice. For the government, there is a need to design incentives that attract new entrants and sustain the pipeline from academic study into professional practice. Industry stakeholders, particularly larger firms, should consider ways to support smaller practices to remain viable, ensuring diversity and competition in the audit market. Academia has a role in tailoring curricula and research to equip future auditors with skills for an increasingly complex and technology-driven environment. Looking ahead, artificial intelligence (AI) presents both challenges and opportunities. AI can reduce pressures from auditor shortages by automating routine tasks and improving efficiency. However, it also brings risks, including ethical concerns, potential skill displacement, and a digital divide that may disadvantage smaller firms without resources to invest in such technologies. Strategically, government, academia, and industry in South Africa must collaborate to integrate AI responsibly, ensuring it supplements rather than undermines the assurance function. Strengthening the RA pipeline will require educational and regulatory reform, along with deliberate efforts to reposition auditing as a viable and rewarding career. The insights here provide a foundation for reimagining a resilient and future-ready audit ecosystem in South Africa.

15. Limitations

A key limitation of this study is its exclusive reliance on the perspectives of registered auditors. It does not capture the views of audit clients or regulatory bodies such as IRBA and SAICA. The study uses a relatively small sample, and the absence of input from stakeholders outside the auditing profession limits the scope of the analysis. While the identified themes are significant, they should be seen as indicative rather than exhaustive. Further research, especially studies including broader stakeholder perspectives, would help confirm and expand these findings.

16. Future Research Recommendations

Future research should expand the scope to include input from clients, public stakeholders, and professional bodies to develop a fuller understanding of the systemic issues affecting the profession. In conclusion, the chapter emphasises the urgent need for collaborative, cross-sector interventions to revitalise the audit profession.