Tanning Bed Legislation for Minors: A Comprehensive International Comparison

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Exceptions to the General Search Procedure

2.2. Presentation of Findings

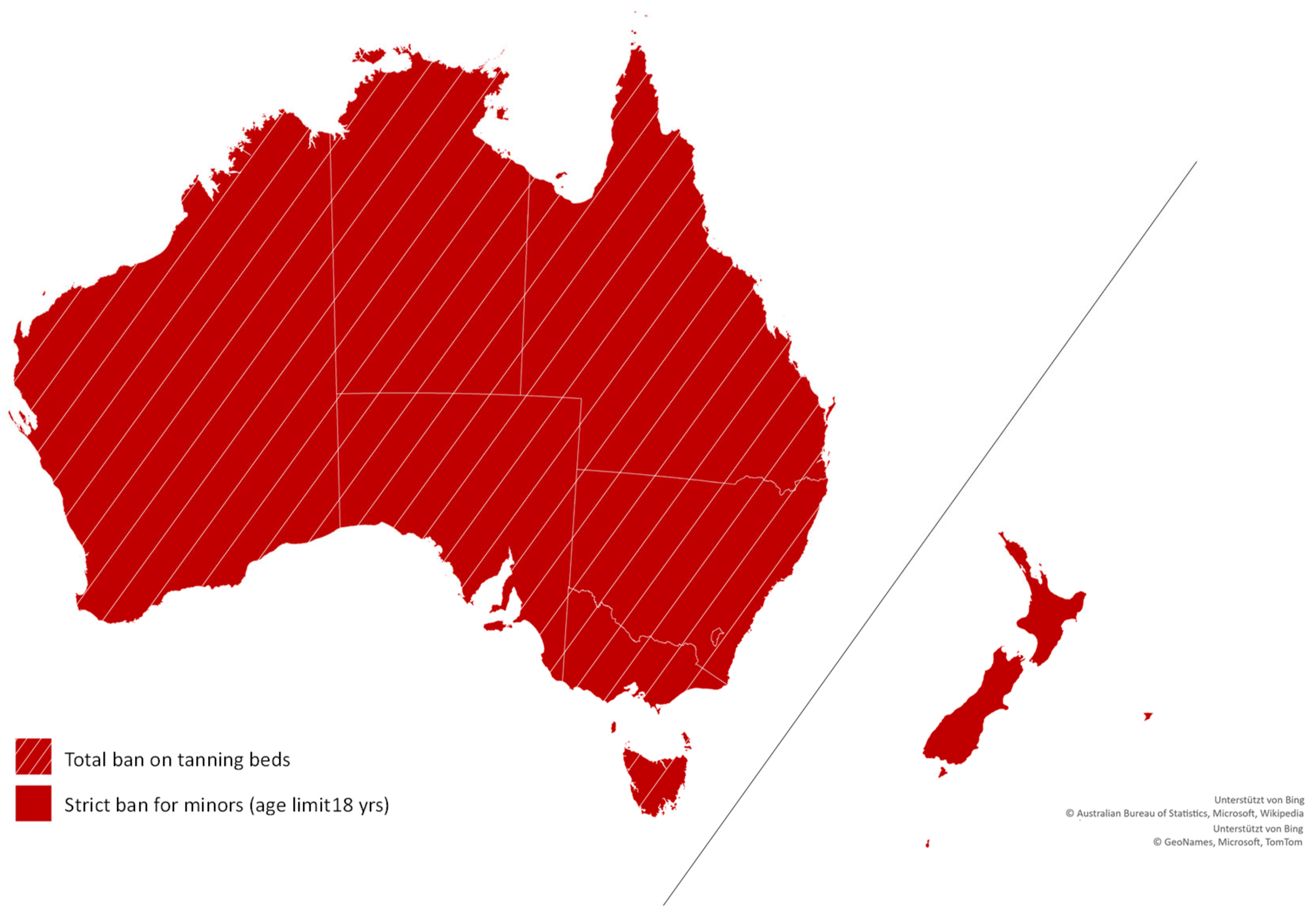

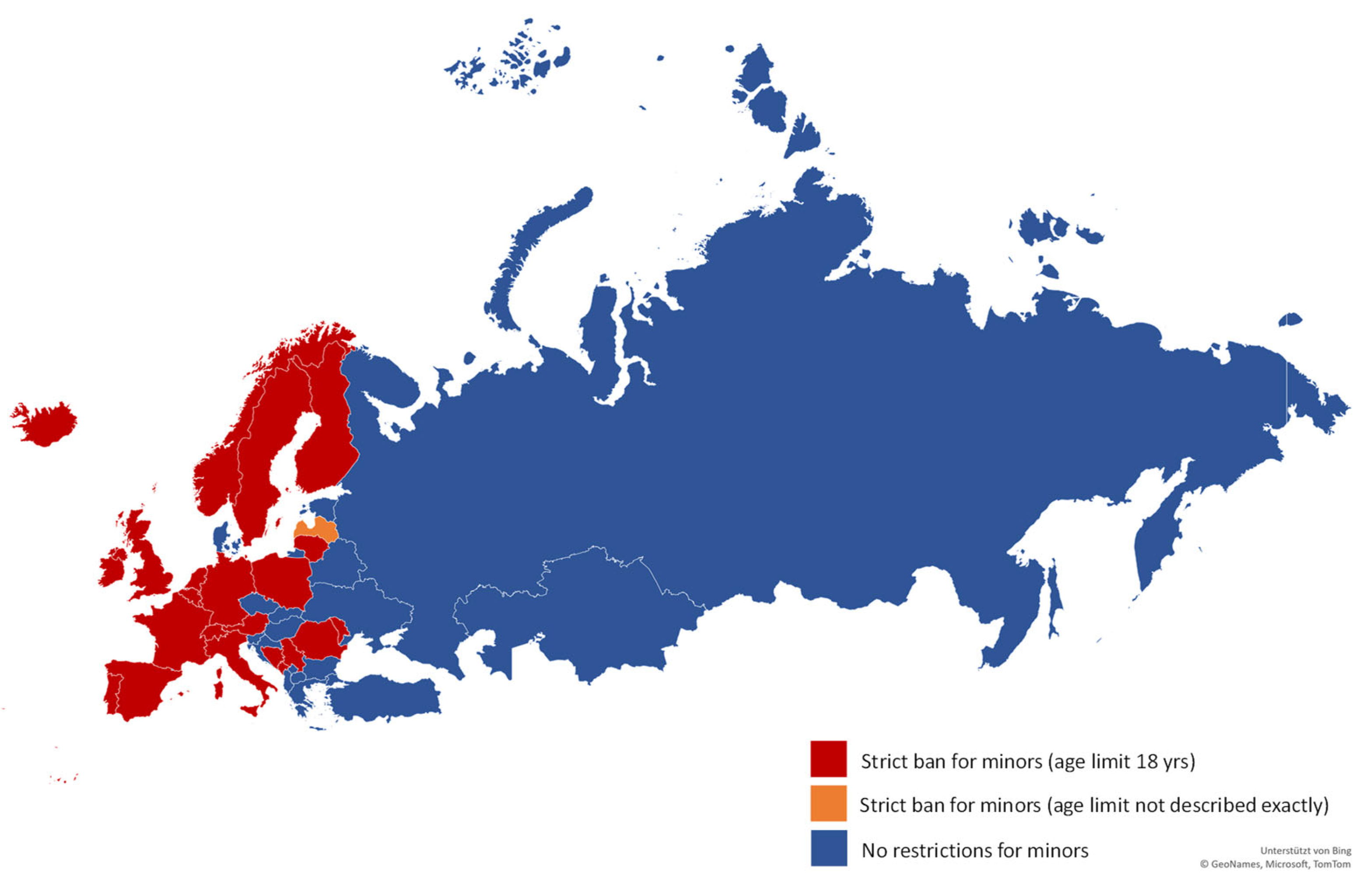

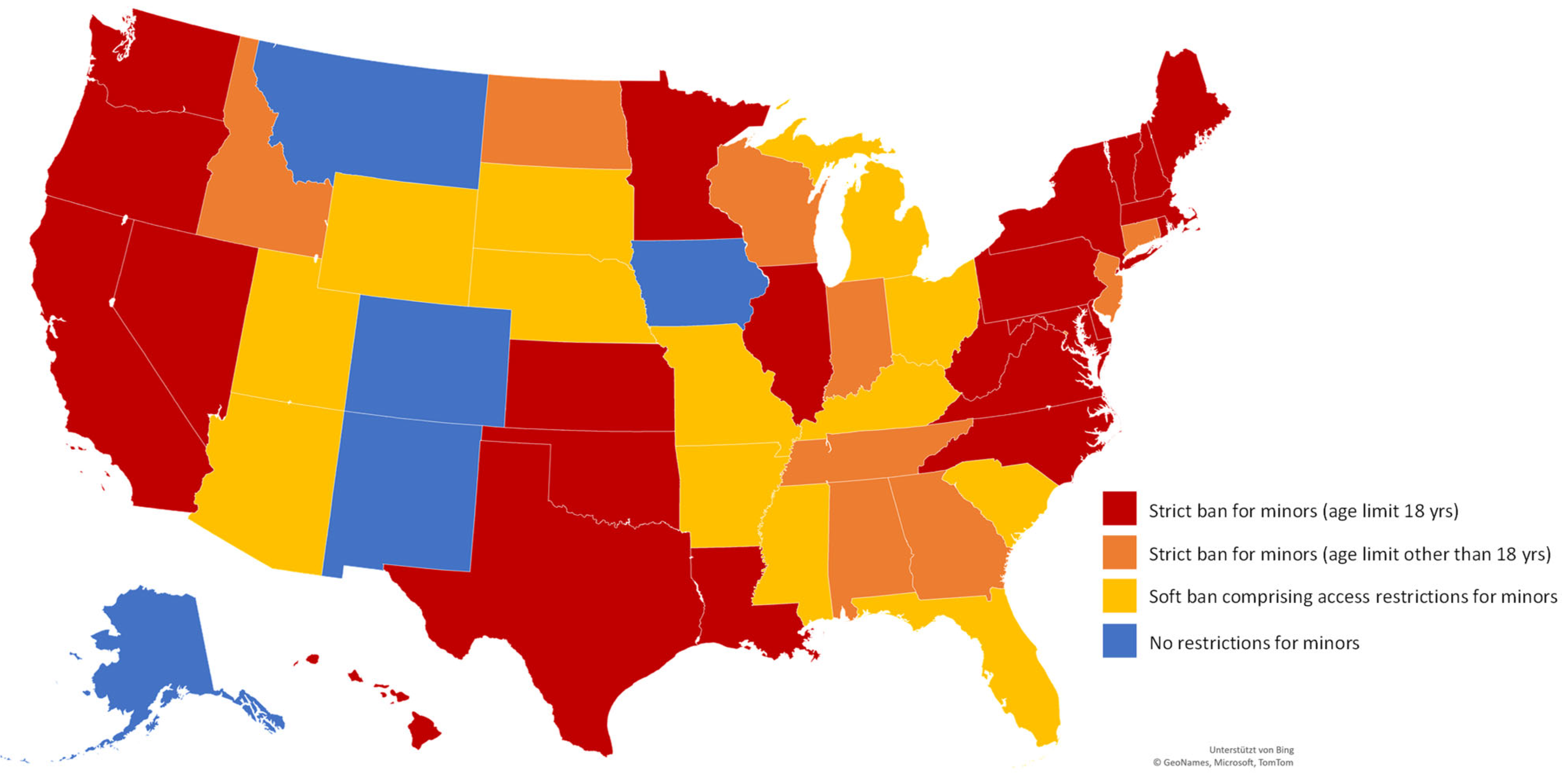

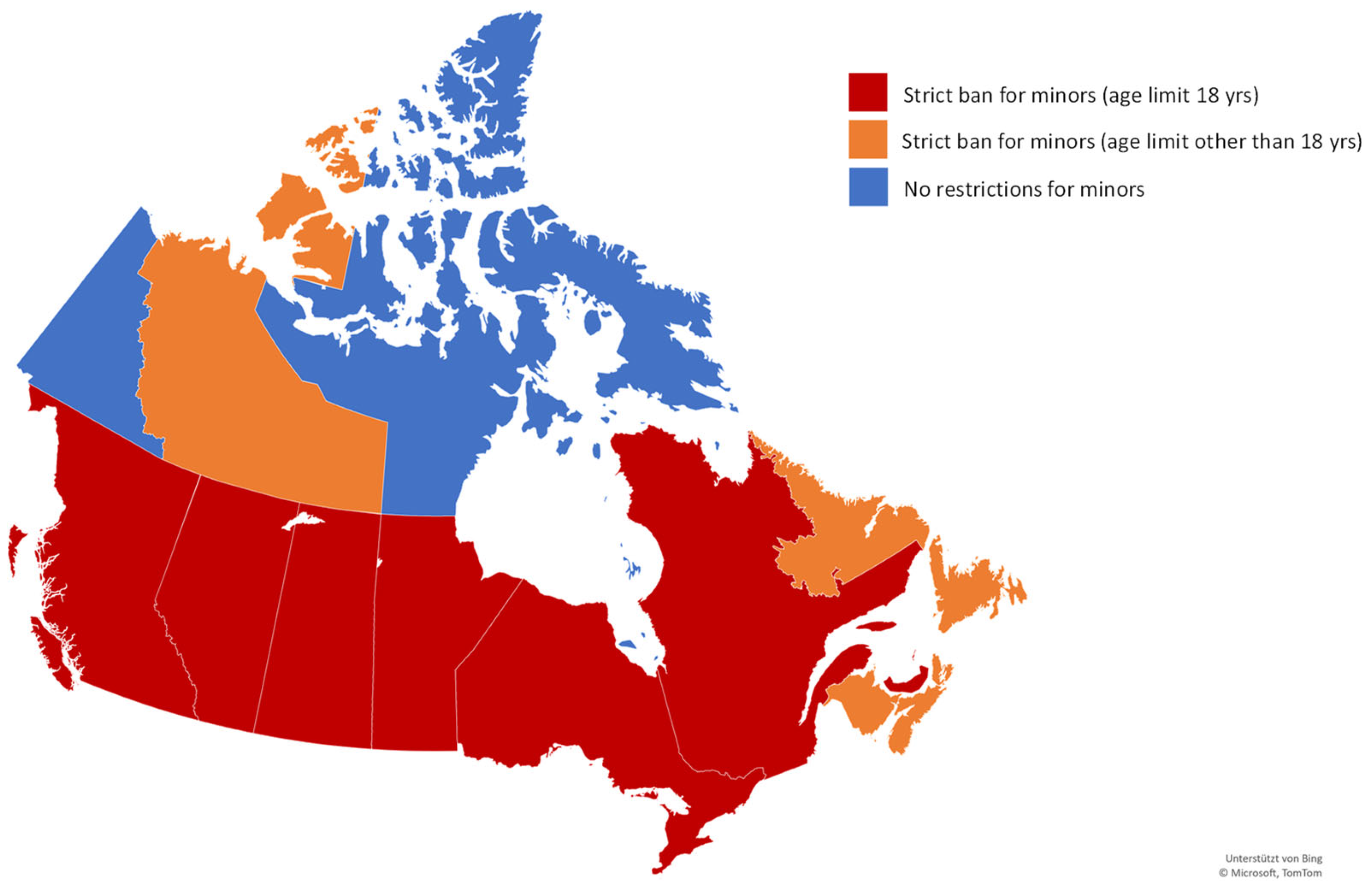

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Møller, K.I.; Kongshoj, B.; Philipsen, P.A.; Thomsen, V.O.; Wulf, H.C. How Finsen’s light cured lupus vulgaris. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2005, 21, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göring, H.D. In memoriam: Niels Ryberg Finsen. Hautarzt 2004, 55, 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, W.; Gilson, N. Quarzglas und Quarzgut. In Heraeus—Pioniere der Werkstofftechnologie: Von der Hanauer Platinschmelze zum internationalen Technologieunternehmen; Kaiser, W., Gilson, N., Eds.; Piper: München, Germany, 2001; pp. 107–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, F. Erfindung der Sonnenbank—Wer Rastet, der Röstet. 2016. Available online: http://www.spiegel.de/einestages/sonnenbank-erfinder-friedrich-wolff-geschichte-des-solariums-a-1065420.html (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Oliphant, J.A.; Forster, J.L.; McBride, C.M. The use of commercial tanning facilities by suburban Minnesota adolescents. Am. J. Public Health 1994, 84, 476–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wichstrom, L. Predictors of Norwegian adolescents’ sunbathing and use of sunscreen. Health Psychol. 1994, 13, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cokkinides, V.E.; Weinstock, M.A.; O’Connell, M.C.; Thun, M.J. Use of indoor tanning sunlamps by US youth, ages 11–18 years, and by their parent or guardian caregivers: Prevalence and correlates. Pediatrics 2002, 109, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jopson, J.A.; Reeder, A.I. An audit of Yellow Pages telephone directory listings of indoor tanning facilities and services in New Zealand, 1992–2006. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2008, 32, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görig, T.; Schneider, S.; Schilling, L.; Diehl, K. Attractiveness as a motive for tanning: Results of representative nationwide survey in Germany. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2020, 36, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.A.; Sorace, M.; Spencer, J.; Siegel, D.M. The indoor UV tanning industry: A review of skin cancer risk, health benefit claims, and regulation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 53, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, A.J.; English, J.S.; MacKie, R.M.; O’Doherty, C.J.; Hunter, J.A.; Clark, J.; Hole, D.J. Fluorescent lights, ultraviolet lamps, and risk of cutaneous melanoma. BMJ 1988, 297, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Autier, P.; Dore, J.F.; Lejeune, F.; Koelmel, K.F.; Gefeller, O.; Hille, P.; Cesarini, J.P.; Lienard, D.; Liabeuf, A.; Joarlette, M.; et al. Cutaneous malignant melanoma and exposure to sunlamps or sunbeds: An EORTC multicenter case-control study in Belgium, France and Germany. EORTC Melanoma Cooperative Group. Int. J. Cancer 1994, 58, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerdahl, J.; Olsson, H.; Masback, A.; Ingvar, C.; Jonsson, N.; Brandt, L.; Jonsson, P.E.; Moller, T. Use of sunbeds or sunlamps and malignant melanoma in southern Sweden. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1994, 140, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.T.; Dubrow, R.; Zheng, T.; Barnhill, R.L.; Fine, J.; Berwick, M. Sunlamp use and the risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma: A population-based case-control study in Connecticut, USA. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1998, 27, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walter, S.D.; King, W.D.; Marrett, L.D. Association of cutaneous malignant melanoma with intermittent exposure to ultraviolet radiation: Results of a case-control study in Ontario, Canada. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1999, 28, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Westerdahl, J.; Ingvar, C.; Masback, A.; Jonsson, N.; Olsson, H. Risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma in relation to use of sunbeds: Further evidence for UV-A carcinogenicity. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 82, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Husain, Z.; Pathak, M.A.; Flotte, T.; Wick, M.M. Role of ultraviolet radiation in the induction of melanocytic tumors in hairless mice following 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene application and ultraviolet irradiation. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 4964–4970. [Google Scholar]

- Kappes, U.P.; Luo, D.; Potter, M.; Schulmeister, K.; Runger, T.M. Short- and long-wave UV light (UVB and UVA) induce similar mutations in human skin cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ridley, A.J.; Whiteside, J.R.; McMillan, T.J.; Allinson, S.L. Cellular and sub-cellular responses to UVA in relation to carcinogenesis. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2009, 85, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Artificial Tanning Sunbeds: Risks and Guidance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Gosselin, S.; McWhirter, J.E. Assessing the content and comprehensiveness of provincial and territorial indoor tanning legislation in Canada. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res. Policy Pract. 2019, 39, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghissassi, F.; Baan, R.; Straif, K.; Grosse, Y.; Secretan, B.; Bouvard, V.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Freeman, C.; Galichet, L.; et al. A review of human carcinogens-part D: Radiation. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 751–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on Artificial Ultraviolet (UV) Light and Skin Cancer. The association of use of sunbeds with cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers: A systematic review. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 120, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniol, M.; Autier, P.; Boyle, P.; Gandini, S. Cutaneous melanoma attributable to sunbed use: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2012, 345, e4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Colantonio, S.; Bracken, M.B.; Beecker, J. The association of indoor tanning and melanoma in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, e818–e841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehner, M.R.; Shive, M.L.; Chren, M.M.; Han, J.; Qureshi, A.A.; Linos, E. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2012, 345, e5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Artificial Tanning Devices: Public Health Interventions to Manage Sunbeds; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Balk, S.J. Ultraviolet radiation: A hazard to children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e791–e817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fiessler, C.; Pfahlberg, A.B.; Keller, A.K.; Radespiel-Troger, M.; Uter, W.; Gefeller, O. Association between month of birth and melanoma risk: Fact or fiction? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gefeller, O.; Diehl, K. Children and Ultraviolet Radiation. Children 2022, 9, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfahlberg, A.; Kolmel, K.F.; Gefeller, O. Timing of excessive ultraviolet radiation and melanoma: Epidemiology does not support the existence of a critical period of high susceptibility to solar ultraviolet radiation- induced melanoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001, 144, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.C.; Wallingford, S.C.; McBride, P. Childhood exposure to ultraviolet radiation and harmful skin effects: Epidemiological evidence. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2011, 107, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gefeller, O.; Tarantino, J.; Lederer, P.; Uter, W.; Pfahlberg, A.B. The relation between patterns of vacation sun exposure and the development of acquired melanocytic nevi in German children 6–7 years of age. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 165, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whiteman, D.C.; Whiteman, C.A.; Green, A.C. Childhood sun exposure as a risk factor for melanoma: A systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Causes Control 2001, 12, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.G.; Hainsworth, R.; Eden, M.; Epton, T.; Lorigan, P.; Grant, M.; Green, A.C.; Payne, K. Sunbed Use among 11- to 17-Year-Olds and Estimated Number of Commercial Sunbeds in England with Implications for a “Buy-Back” Scheme. Children 2021, 8, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möllers, T.; Pischke, C.R.; Zeeb, H. Do tanning salons adhere to new legal regulations? Results of a simulated client trial in Germany. Radiat. Environ. Biophys 2016, 55, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimann, J.; McWhirter, J.E.; Papadopoulos, A.; Dewey, C. A systematic review of compliance with indoor tanning legislation. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robsahm, T.E.; Stenehjem, J.S.; Berge, L.A.M.; Veierod, M.B. Prevalence of Indoor Tanning Among Teenagers in Norway Before and After Enforcement of Ban for Ages Under 18 Years. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, adv00127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, K.; Bock, C.; Greinert, R.; Breitbart, E.W.; Schneider, S. Use of sunbeds by minors despite a legal regulation: Extent, characteristics, and reasons. J. Public Health 2013, 21, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, K.; Görig, T.; Greinert, R.; Breitbart, E.W.; Schneider, S. Trends in Tanning Bed Use, Motivation, and Risk Awareness in Germany: Findings from Four Waves of the National Cancer Aid Monitoring (NCAM). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qin, J.; Holman, D.M.; Jones, S.E.; Berkowitz, Z.; Guy, G.P., Jr. State Indoor Tanning Laws and Prevalence of Indoor Tanning Among US High School Students, 2009–2015. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, G.P., Jr.; Berkowitz, Z.; Jones, S.E.; Olsen, E.O.; Miyamoto, J.N.; Michael, S.L.; Saraiya, M. State indoor tanning laws and adolescent indoor tanning. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e69–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.G.; Sinclair, C.; Cleaves, N.; Makin, J.K.; Rodriguez-Acevedo, A.J.; Green, A.C. Consequences of banning commercial solaria in 2016 in Australia. Health Policy 2020, 124, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, K.; Görig, T.; Schilling, L.; Greinert, R.; Breitbart, E.W.; Schneider, S. Profile of sunless tanning product users: Results from a nationwide representative survey. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2019, 35, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dellavalle, R.P.; Parker, E.R.; Cersonsky, N.; Hester, E.J.; Hemme, B.; Burkhardt, D.L.; Chen, A.K.; Schilling, L.M. Youth access laws: In the dark at the tanning parlor? Arch. Dermatol. 2003, 139, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Francis, S.O.; Burkhardt, D.L.; Dellavalle, R.P. 2005: A banner year for new US youth access tanning restrictions. Arch. Dermatol. 2005, 141, 524–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, J.A.; Francis, S.O.; Burkhardt, D.L.; Dellavalle, R.P. Indoor UV tanning youth access laws: Update 2007. Arch. Dermatol. 2007, 143, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, M.T.; Bui, M.; Amir, M.; Burkhardt, D.L.; Chen, A.K.; Dellavalle, R.P. Legislation restricting access to indoor tanning throughout the world. Arch. Dermatol. 2012, 148, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Longo, M.I.; Bulliard, J.L.; Correia, O.; Maier, H.; Magnusson, S.M.; Konno, P.; Goad, N.; Duarte, A.F.; Olah, J.; Nilsen, L.T.N.; et al. Sunbed use legislation in Europe: Assessment of current status. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33 (Suppl. 2), 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Del Colombo, L.; Vasile, O. Actions taken by the European commission to address the safety of sunbeds. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodriguez-Acevedo, A.J.; Green, A.C.; Sinclair, C.; van Deventer, E.; Gordon, L.G. Indoor tanning prevalence after the International Agency for Research on Cancer statement on carcinogenicity of artificial tanning devices: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, C.Y.; Kunene, Z.; Visser, W.; Mathee, A. Sunbeds: A burning issue needing attention in South Africa. South Afr. Med. J. 2018, 108, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcez, J. Battle for Brazil—The state vs tanning. Skin Cancer Found. J. 2011, 12, 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, C.A.; Makin, J.K.; Tang, A.; Brozek, I.; Rock, V. The role of public health advocacy in achieving an outright ban on commercial tanning beds in Australia. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e7–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, L.T.; Hannevik, M.; Veierod, M.B. Ultraviolet exposure from indoor tanning devices: A systematic review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 174, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/system/files/2022-02/eu_cancer-plan_en_0.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diehl, K.; Lindwedel, K.S.; Mathes, S.; Görig, T.; Gefeller, O. Tanning Bed Legislation for Minors: A Comprehensive International Comparison. Children 2022, 9, 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060768

Diehl K, Lindwedel KS, Mathes S, Görig T, Gefeller O. Tanning Bed Legislation for Minors: A Comprehensive International Comparison. Children. 2022; 9(6):768. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060768

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiehl, Katharina, Karla S. Lindwedel, Sonja Mathes, Tatiana Görig, and Olaf Gefeller. 2022. "Tanning Bed Legislation for Minors: A Comprehensive International Comparison" Children 9, no. 6: 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060768

APA StyleDiehl, K., Lindwedel, K. S., Mathes, S., Görig, T., & Gefeller, O. (2022). Tanning Bed Legislation for Minors: A Comprehensive International Comparison. Children, 9(6), 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060768