A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects by Bullying and School Exclusion on Subjective Happiness in 10-Year-Old Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Data Analysis Design

3. Results

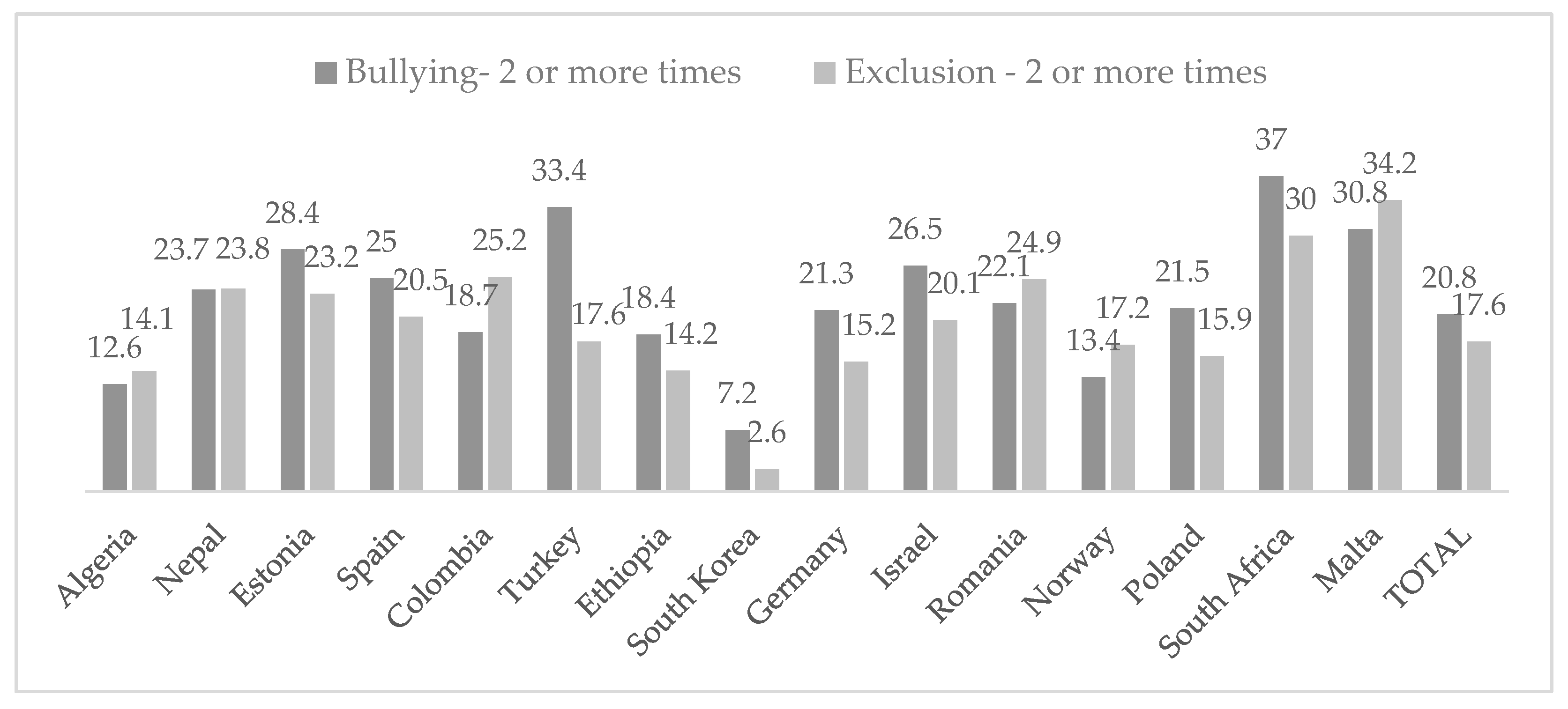

3.1. Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

3.2. Associations between Bullying, School Exclusion and Subjective Happiness

3.3. Regression Analyses to Examine the Combined Effects of School Bullying and Exclusion on Child Happiness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfaro, J.; Guzmán, J.; Reyes, F.; García, C.; Varela, J.; Sirlopú, D. Satisfacción global con la vida y satisfacción escolar en estudiantes Chilenos [Overall life satisfaction and school satisfaction in Chilean students]. Psykhe Rev. De La Esc. De Psicol. 2016, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Bacete, F.-J.; Sureda García, I.; Monjas Casares, M.I. El rechazo entre iguales en la educación primaria: Una panorámica general. An. Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 2010, 26, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. School Violence and Bullying: Global Status and Trends, Drivers and Consequences. 2018. Available online: http://www.infocoponline.es/pdf/BULLYING.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Bender, T.A. Assessment of Subjective Well-Being during Childhood and Adolescence. In Handbook of Classroom Assessment; Elsevier BV: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Lucas, R.E. Personality, culture, and subjective well being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-García, Z.; Álvarez-García, D.; y Rodríguez, C. Predictores de ser víctima de acoso escolar en Educación Primaria: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. De Psicol. Y Educ. 2020, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymel, S.; Swearer, S.M. Four Decades of Research on School Bullying. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modecki, K.L.; Minchin, J.; Harbaugh, A.G.; Guerra, N.G.; Runions, K.C. Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchin, J.W.; Hinduja, S. Tween Cyberbullying in 2020. Cyberbullying Research Center and Cartoon Network. 2020. Available online: https://i.cartoonnetwork.com/stop-bullying/pdfs/CN_Stop_Bullying_Cyber_Bullying_Report_9.30.20.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Graham, S.; Bellmore, A.D.; Mize, J. Peer Victimization, Aggression, and Their Co-Occurrence in Middle School: Pathways to Adjustment Problems. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2006, 34, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.C.; Valois, R.F.; Huebner, E.S.; Drane, J.W. Life Satisfaction and Peer Victimization among USA Public High School Adolescents. Child Ind. Res. 2011, 4, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, E.; Murgui, S.; Musitu, G. Psychological adjustment in bullies and victims of school violence. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2009, 24, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, G.; Pozzoli, T. Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paget, A.; Parker, C.; Heron, J.; Logan, S.; Henley, W.; Emond, A.; Ford, T. Which children and young people are excluded from school? Findings from a large British birth cohort study, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sproston, K.; Sedgewick, F.; Crane, L. Autistic girls and school exclusion: Perspectives of students and their parents. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, N.; Wolstenholme, C. ‘I didn’t stand a chance’: How parents experience the exclusions appeal tribunal. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2016, 20, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Levinson, M. ‘I don’t need pink hair here’: Should we be seeking to ‘reintegrate’ youngsters without challenging mainstream school cultures? Int. J. Sch. Disaffection 2016, 12, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C. Children, Their Voices and Their Experiences of School: What Does the Evidence Tell Us? Cambridge Primary Review Trust: York, UK, 2014; Available online: https://cprtrust.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2014/12/FINAL-VERSION-Carol-Robinson-Children-their-Voices-and-theirExperiences-of-School.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Rettew, D.C.; Pawlowski, S. Bullying. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Educational Statistics. Student Reports of Bullying: Results from the 2017 School Crime Supplement to the National Victimization Survey. US Department of Education. 2019. Available online: http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2015056 (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Perren, S.; Ettekal, I.; Ladd, G. The impact of peer victimization on later maladjustment: Mediating and moderating effects of hostile and self-blaming attributions. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunstein Klomek, A.; Sourander, A.; Gould, M. The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: A review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Rev. Can. Psychiatr. 2010, 55, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydenberk, R.A.; Heydenberk, W.R. Bullying reduction and subjective wellbeing: The benefits of reduced bullying reach far beyond the victim. Int. J. Wellbeing 2017, 7, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, R.; Ruiz-Oliva, R.; Larrañaga, E.; Yubero, S. The impact of cyberbullying and social bullying on optimism, global and school-related happiness and life satisfaction among 10-12-year-old schoolchildren. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2015, 10, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallion, G.; Feder, J. Student Bullying: Overview of Research, Federal Initiatives, and Legal Issues; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43254.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Davis, S.; Nixon, C. The Youth Voice Research Project: Victimization and Strategies. 2010. Available online: http://njbullying.org/documents/YVPMarch2010.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Trotman, D.; Tucker, S.; Martyn, M. Understanding problematic pupil behaviour: Perceptions of pupils and behaviour coordinators on secondary school exclusion in an English city. Educ. Res. 2015, 57, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.L.D.; Cummins, R.A.; McPherson, W. An Investigation into the Cross-Cultural Equivalence of the Personal Wellbeing Index. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 72, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, A.; Valera, S. Los fundamentos de la intervención psicosocial. Interv. Psicosoc. 2007, 1, 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- López Hernáez, L.; Ovejero Bruna, M. Percepción de las consecuencias del bullying más allá de las aulas: Una aproximación cuasi-cuantitativa. Pensam. Educ. Rev. De Investig. Latinoam. (PEL) 2018, 55, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboyega, L.O.; Okesina, F.A.; Jacob, O.A. Family Relationship and Bullying Behaviour among Students with Disabilities in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. Int. J. Instr. 2017, 10, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, R.; Oyanedel, J.; Torres, J. Efectos del apoyo familiar, amigos y de escuela sobre el bullying y bienestar subjetivo en estudiantes de nivel secundario de Chile y Brasil. Apunt. Cienc. Soc. 2018, 8, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Konu, A.I.; Lintonen, T.P.; Autio, V.J. Evaluation of well-being in schools–a multilevel analysis of general subjective well-being. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2002, 13, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, K.E.N. Effects of peer victimization in schools and perceived social support on adolescent well-being. J. Adolesc. 2000, 23, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansel, T.R.; Overpeck, M.; Pilla, R.S.; Ruan, W.J.; Simons-Morton, B.; Scheidt, P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 2001, 285, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grills, A.E.; Ollendick, T.H. Peer victimization, global self-worth, and anxiety in middle school children. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2002, 31, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansel, T.R.; Craig, W.; Overpeck, M.D.; Saluja, G.; Ruan, W.J. Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviors and psychosocial adjustment. Arch. Pediatrics Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, G.; Blanco, J.L. El «Buen trato», programa de prevención del acoso escolar, otros tipos de violencia y dificultades de relación: Una experiencia de éxito con alumnos, profesores y familia. Rev. De Estud. De Juv. 2017, 115–136. Available online: https://bit.ly/3by6geW (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Mäkelä, T.; López-Catalán, B. Programa de convivencia y anti-acoso escolar finlandés KiVa. Impacto y reflexión. An. De La Fund. Canis Majoris 2018, 2, 234–258. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. Evidence-Based Approaches in Positive Education: Implementing a Strategic Framework for Well-Being in Schools; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Palomera, R. Educando para la felicidad. In Emociones Positivas; Fernández-Abascal, E.G., Ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 247–273. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, R.P. Psicología positiva en la escuela: Un cambio con raíces profundas. Pap. Del Psicólogo 2017, 37, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrish, J.M.; Williams, P.; O’Connor, M.; Robinson, J. An applied framework for positive education. Int. J. Wellbeing 2013, 3, 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Cases, C.; Davo-Blanes, M.C.; Ferrer-Cascales, R.; Sanz-Barbero, B.; Albaladejo-Blázquez, N.; Sánchez-San Segundo, M.; Lillo-Crespo, M.; Bowes, N.; Neves, S.; Mocanu, V.; et al. Lights4Violence: A quasi-experimental educational intervention in six European countries to promote positive relationships among adolescents. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J. World Happiness Report. Summary Spanish. 2015. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2015/WHR-2015-summary_final-ES.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2022).

| Boys %(n) | Girls %(n) | Total n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 49.4 (385) | 50.6 (395) | 780 |

| Nepal | 49.7 (489) | 50.3 (494) | 983 |

| Estonia | 51.6 (441) | 48.4 (413) | 854 |

| Spain | 50.2 (445) | 49.8 (441) | 886 |

| Colombia | 47.9 (444) | 52.1 (483) | 927 |

| Turkey | 50.4 (450) | 49.6 (443) | 893 |

| Ethiopia | 49 (274) | 51 (285) | 559 |

| South Korea | 48.9 (1192) | 51.1 (1246) | 2438 |

| Germany | 48 (220) | 52 (238) | 458 |

| Israel | 49.9 (204) | 50.1 (205) | 409 |

| Romania | 52.8 (546) | 47.2 (489) | 1035 |

| Norway | 51.3 (326) | 48.7 (309) | 635 |

| Poland | 51.4 (300) | 48.6 (284) | 584 |

| South Africa | 48.4 (513) | 51.6 (548) | 1061 |

| Malta | 62 (75) | 38 (46) | 121 |

| Total | 49.9 (6304) | 50.1 (6319) | 12,623 |

| Subjective Happiness 0–10 | School Bullying 0–3 | School Exclusion 0–3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 8.87 (2.03) | 0.48 (0.85) | 0.57 (0.90) |

| Nepal | 8.64 (2.07) | 0.82 (1.02) | 0.86 (1.01) |

| Estonia | 8.16 (2.09) | 0.91 (1.13) | 0.76 (1.02) |

| Spain | 9.06 (1.57) | 0.79 (1.08) | 0.67 (0.97) |

| Colombia | 9.20 (1.71) | 0.62 (1.00) | 0.83 (1.11) |

| Turkey | 9.33 (1.77) | 1.09 (1.14) | 0.55 (0.99) |

| Ethiopia | 8.61 (2.08) | 0.62 (0.96) | 0.47 (0.88) |

| South Korea | 8.24 (2.05) | 0.27 (0.69) | 0.10 (0.44) |

| Germany | 8.32 (1.97) | 0.67 (1.00) | 0.53 (0.93) |

| Israel | 8.57 (2.39) | 0.84 (1.07) | 0.70 (1.08) |

| Romania | 9.35 (1.46) | 0.69 (1.00) | 0.78 (1.13) |

| Norway | 8.86 (1.91) | 0.48 (0.84) | 0.58 (0.93) |

| Poland | 8.86 (1.65) | 0.69 (1.04) | 0.53 (0.93) |

| South Africa | 8.67 (2.35) | 1.17 (1.25) | 0.96 (1.18) |

| Malta | 8.50 (2.12) | 1.03 (1.14) | 1.08 (1.18) |

| Total | 8.73 (1.99) | 0.69 (1.03) | 0.59 (0.98) |

| F | Partial eta Squared | Never M(SD) | Once M(SD) | 2 or More Times M(SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 2.76 | 0.007 | 8.96 (1.94) | 8.90 (1.54) | 8.43 (2.78) |

| Nepal | 0.49 | 0.001 | 8.62 (2.05) | 8.78 (1.94) | 8.61 (2.17) |

| Estonia | 12.47 *** | 0.030 | 8.45 (1.81) | 8.30 (1.97) | 7.62 (2.50) |

| Spain | 11.67 *** | 0.027 | 9.26 (1.31) | 8.99 (1.72) | 8.67 (1.82) |

| Colombia | 1.45 | 0.003 | 9.24 (1.74) | 9.22 (1.46) | 8.99 (1.82) |

| Turkey | 8.52 *** | 0.019 | 9.55 (1.58) | 9.42 (1.53) | 8.99 (2.08) |

| Ethiopia | 5.78 ** | 0.021 | 8.83 (1.88) | 8.19 (2.36) | 8.24 (2.35) |

| South Korea | 29.63 *** | 0.025 | 8.40 (1.94) | 7.87 (2.18) | 7.25 (2.60) |

| Germany | 14.91 *** | 0.067 | 8.73 (1.67) | 7.60 (2.19) | 7.73 (2.33) |

| Israel | 1.49 | 0.008 | 8.75 (2.21) | 8.51 (2.45) | 8.25 (2.64) |

| Romania | 9.68 *** | 0.019 | 9.50 (1.31) | 9.30 (1.32) | 9.00 (1.89) |

| Norway | 17.83 *** | 0.057 | 9.18 (1.62) | 8.24 (2.29) | 8.15 (2.31) |

| Poland | 14.02 *** | 0.051 | 9.12 (1.32) | 8.82 (1.60) | 8.20 (2.21) |

| South Africa | 3.17 * | 0.006 | 8.87 (2.14) | 8.50 (2.35) | 8.50 (2.58) |

| Malta | 3.59 * | 0.059 | 8.94 (1.45) | 7.64 (2.25) | 8.47 (2.66) |

| Total | 52.16 *** | 0.009 | 8.87 (1.84) | 8.66 (1.99) | 8.42 (2.35) |

| F | Partial eta Squared | Never M(SD) | Once M(SD) | 2 or More Times M(SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 16.31 *** | 0.042 | 9.09 (1.72) | 8.95 (1.76) | 7.89 (3.05) |

| Nepal | 4.70 ** | 0.012 | 8.81 (1.82) | 8.68 (2.12) | 8.25 (2.45) |

| Estonia | 9.91 *** | 0.024 | 8.47 (1.85) | 7.82 (2.17) | 7.81 (2.37) |

| Spain | 21.36 *** | 0.050 | 9.32 (1.30) | 8.95 (1.28) | 8.44 (2.18) |

| Colombia | 4.62 * | 0.011 | 9.31 (1.65) | 9.30 (1.53) | 8.90 (1.89) |

| Turkey | 17.38 *** | 0.039 | 9.56 (1.40) | 8.94 (2.26) | 8.75 (2.25) |

| Ethiopia | 5.07 ** | 0.018 | 8.78 (1.92) | 8.13 (2.45) | 8.16 (2.37) |

| South Korea | 22.58 *** | 0.019 | 8.36 (1.97) | 7.33 (2.21) | 7.08 (2.84) |

| Germany | 11.60 *** | 0.053 | 8.63 (1.66) | 8.10 (1.84) | 7.42 (2.69) |

| Israel | 5.24 ** | 0.027 | 8.85 (1.88) | 8.02 (2.96) | 8.04 (3.21) |

| Romania | 0.42 | 0.001 | 9.38 (1.51) | 9.25 (1.51) | 9.34 (1.31) |

| Norway | 27.86 *** | 0.087 | 9.25 (1.49) | 8.69 (1.89) | 7.78 (2.59) |

| Poland | 31.16 *** | 0.111 | 9.23 (1.13) | 8.57 (1.66) | 7.81 (2.50) |

| South Africa | 7.74 *** | 0.014 | 8.93 (2.04) | 8.44 (2.60) | 8.33 (2.66) |

| Malta | 1.14 | 0.020 | 8.79 (1.78) | 8.09 (2.25) | 8.26 (2.51) |

| Total | 70.72 *** | 0.012 | 8.89 (1.80) | 8.59 (2.09) | 8.34 (2.43) |

| Bullying | Exclusion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | β | t | β | t | |

| Algeria | 13.40 *** | −0.02 | −0.50 | −0.18 *** | −4.75 |

| Nepal | 3.27 * | 0.05 | 1.16 | −0.10 * | −2.55 |

| Estonia | 13.19 *** | −0.13 ** | −3.33 | −0.08 * | −2.06 |

| Spain | 25.41 *** | −0.12 ** | −3.40 | −0.18 *** | −5.09 |

| Colombia | 4.70 ** | −0.02 | −0.60 | −0.10 ** | −2.60 |

| Turkey | 17.09 *** | −0.07 | −1.89 | −0.16 *** | −4.37 |

| Ethiopia | 6.81 ** | −0.10 * | −2.19 | −0.09 * | −2.03 |

| South Korea | 35.61 *** | −0.13 *** | −5.88 | −0.08 *** | −3.61 |

| Germany | 13.95 *** | −0.15 ** | −2.66 | −0.15 ** | −2.77 |

| Israel | 5.30 ** | −0.07 | −1.25 | −0.14 ** | −2.70 |

| Romania | 10.45 *** | −0.15 *** | −4.52 | 0.02 | 0.52 |

| Norway | 32.87 *** | −0.13 ** | −3.14 | −0.25 *** | −6.06 |

| Poland | 33.00 *** | −0.10 * | −2.14 | −0.29 *** | −6.12 |

| South Africa | 8.07 *** | −0.04 | −1.27 | −0.11 ** | −3.30 |

| Malta | 1.13 | −0.08 | −0.84 | −0.09 | −0.93 |

| Total | 85.79 *** | −0.06 *** | −6.20 | −0.08 *** | −8.41 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomez-Baya, D.; Garcia-Moro, F.J.; Nicoletti, J.A.; Lago-Urbano, R. A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects by Bullying and School Exclusion on Subjective Happiness in 10-Year-Old Children. Children 2022, 9, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020287

Gomez-Baya D, Garcia-Moro FJ, Nicoletti JA, Lago-Urbano R. A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects by Bullying and School Exclusion on Subjective Happiness in 10-Year-Old Children. Children. 2022; 9(2):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020287

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomez-Baya, Diego, Francisco Jose Garcia-Moro, Javier Augusto Nicoletti, and Rocio Lago-Urbano. 2022. "A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects by Bullying and School Exclusion on Subjective Happiness in 10-Year-Old Children" Children 9, no. 2: 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020287

APA StyleGomez-Baya, D., Garcia-Moro, F. J., Nicoletti, J. A., & Lago-Urbano, R. (2022). A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects by Bullying and School Exclusion on Subjective Happiness in 10-Year-Old Children. Children, 9(2), 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020287