Longitudinal Analysis of Adolescent Adjustment: The Role of Attachment and Emotional Competence

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Adjustment

1.2. Peer Attachment

1.3. Emotional Competencies

1.4. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Psychological Adjustment

2.3.2. Peer Attachment

2.3.3. Emotional Competencies

2.4. Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

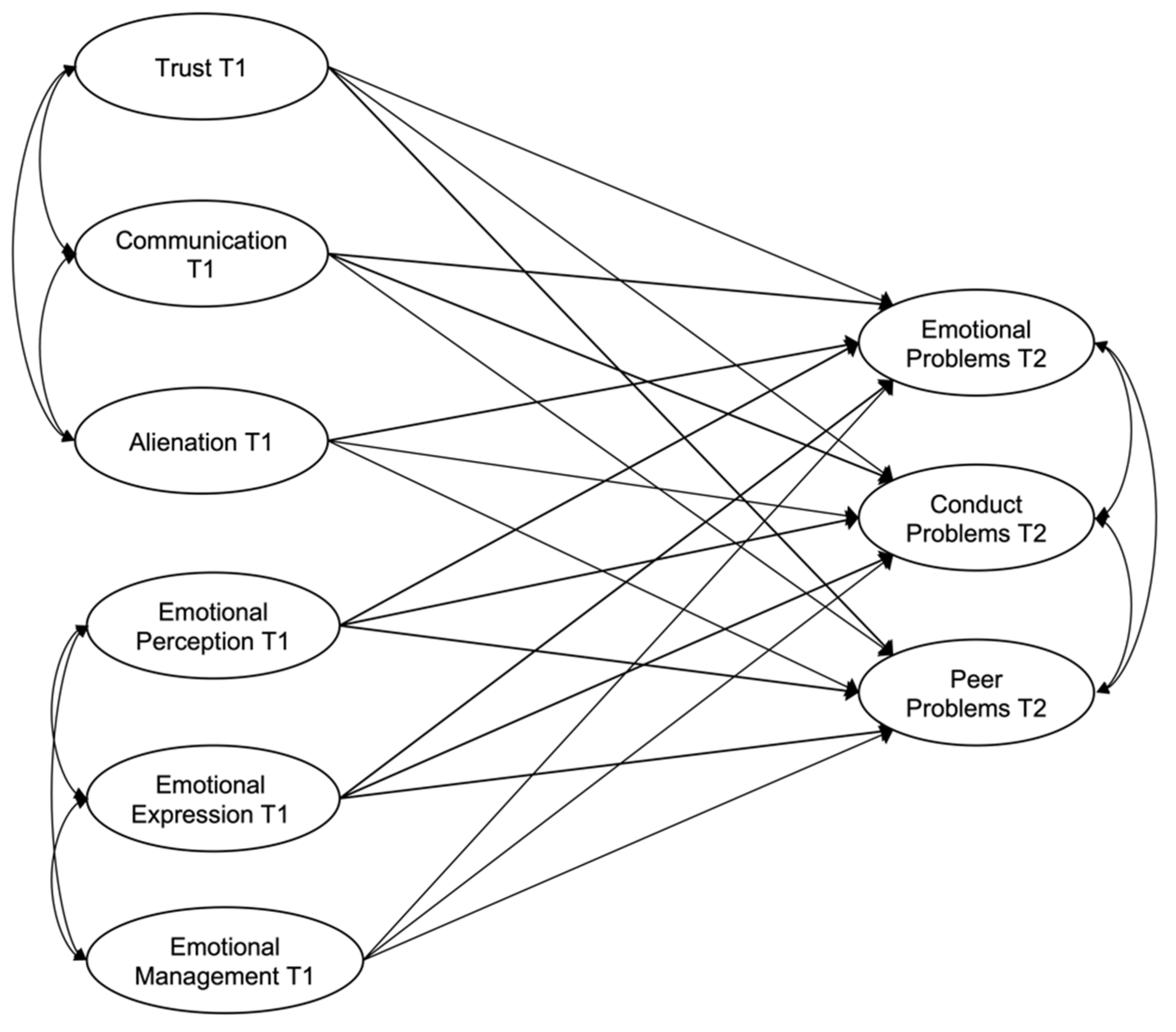

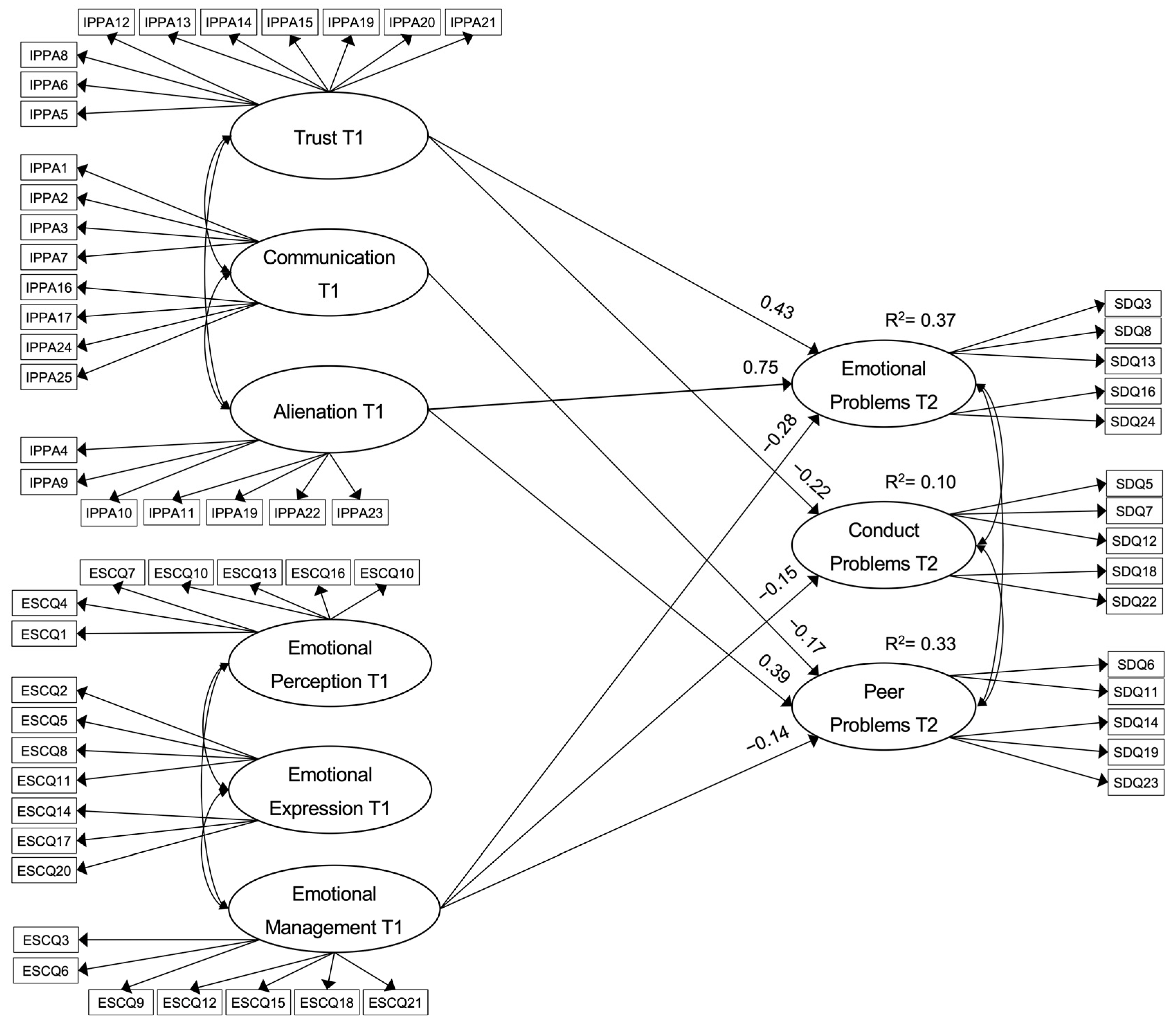

3.2. Structural Equation Model (SEM)

3.3. Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Díaz, D.; Fuentes, I.; Senra, N.C. Adolescencia y autoestima: Su desarrollo desde las instituciones educativas. Rev. Conrado 2018, 14, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood: A Cultural Approach, 3rd ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: México, México, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-García, M.D.L.Á.; Lucas-Molina, B.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Pérez-Albéniz, A.; Paino, M. Emotional and behavioral difficulties in adolescence: Relationship with emotional well-being, affect, and academic performance. Ann. Psicol. 2018, 34, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, W.A.; Steinberg, L. Adolescence Development in Interpersonal Context. In Handbokk of Child Psychology: Social, Emocional, and Personality Development, 6th ed.; Eisenberg, N., Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 3, pp. 1003–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeps, K.; Mónaco, E.; Cotolí, A.; Montoya-Castilla, I. The impact of peer attachment on prosocial behavior, emotional difficulties and conduct problems in adolescence: The mediating role of empathy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 939–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. Psychometric Properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, X.; Sun, Q. Exploring psychosocial adjustment profiles in Chinese adolescents from divorced families: The interplay of parental attachment and adolescent’s gender. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 5832–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras, J.A.; Mateu-Martínez, O.; Cejudo, J.; Pérez-González, J.C. Pathways into psychosocial adjustment in children: Modeling the effects of trait emotional intelligence, social-emotional problems, and gender. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ortiz, O.; Zea, R.; Ortega-Ruiz, R.; Romera, E.M. Percepción y motivación social: Elementos predictores de la ansiedad y el ajuste social en adolescentes. Psicol. Educ. 2020, 26, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, E.F. Ajuste psicosocial en la adolescencia: Especial atención a las diferencias de género. In Variables Psicológicas y Educativas Para la Intervención en el Ámbito Escolar. Nuevas Realidades de Análisis; Molero, M.M., Martos, A., Barragán, A.B., Simón, M.M., Sisto, M., del Pino, R.M., Tortosa, B.M., Gázquez, J.J., Pérez, M.C., Eds.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Inchausti, F.; Sastre, S. Evaluación de dificultades emocionales y comportamentales en población infanto-juvenil: El cuestionario de capacidades y dificultades (SDQ). Pap. Psicólogo 2016, 37, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Debbané, M. Schizotypal traits and psychotic-like experiences during adolescence: An update. Psicothema 2017, 29, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- González-Gutiérrez, O.; Navarro, J.; Ortiz, L.; Alarcón-Vásquez, Y.; Ascanio, C.; Trejos-Herrera, A.M. Relación entre prácticas parentales y ajuste psicológico de adolescentes estandarizados. Arch. Venez. Farmacol. Ter. 2019, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Iglesias, A.; Moreno, C. La influencia de las diferencias entre el padre y la madre sobre el ajuste adolescente. Ann. Psicol. 2015, 31, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mattanah, J. Parental attachment, romantic competence, relationship satisfaction, and psychosocial adjustment in emerging adulthood. Pers. Relatsh. 2016, 23, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, R.; Ruiz-Oliva, R.; Larrañaga, E.; Yubero, S. The impact of cyberbullying and social bullying on optimism, global and school-related happiness and life satisfaction among 10-12-year-old schoolchildren. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2015, 10, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Jiménez, M.V.; Quintana-Rey, S. Ideaciones suicidas en adolescentes, relaciones paternofiliales y apego a los iguales. Int. J. Psychol. Ther. 2018, 18, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Paino, M.; Lemos-Giráldez, S.; Muñiz, J. Prevalencia de la sintomatología emocional y comportamental en adolescentes españoles a través de Stengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Rev. Psicopatol. Psicol. Clín. 2011, 16, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Pérez-Albéniz, A. Dificultades emocionales y conductuales y comportamiento prosocial en adolescentes: Un análisis de perfiles latentes. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2020, 13, 202–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Paíno, M.; Aritio-Solana, R. Prevalencia de síntomas emocionales y comportamentales en adolescentes españoles. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2014, 7, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, R.J.R. Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms. In Encyclopedia of Adolescence, 2nd ed.; Levesque, R.J.R., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 903–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic Books: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pattanayak, A.; Sonalika, S.; Singh, M. Importance of peers in adolescent life: A systematic review. Turk. J. Physiother. Rehabil. 2021, 32, 36149. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C. Chinese adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment: The contribution of mothers’ attachment style and adolescents’ attachment to mother. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 37, 2594–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagos, P.; Carvalhais, L. The impact of adolescents’ attachment to peers and parents on aggressive and prosocial behavior: A short-term longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 592144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancinelli, E.; Liberska, H.; Li, J.B.; Espada, J.P.; Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C.; Lis, A.; Salcuni, S. A Cross-Cultural Study on Attachment and Adjustment Difficulties in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Self-Control in Italy, Spain, China, and Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambelli, R.; Laghi, F.; Odorisio, F.; Notari, V. Attachment relationships and Internalizing and Externalizing problems among Italian adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, X.; Fan, X.; Cai, Z.; Hao, S. Profiles of parent and peer attachments of adolescents and associations with psychological outcomes. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 94, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.A.; Cassidy, J. Empathy from infancy to adolescence: An attachment perspective on the development of individual differences. Dev. Rev. 2018, 47, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theisen, J.C.; Fraley, R.C.; Hankin, B.L.; Young, J.F.; Chopik, W.J. How do attachment styles change from childhood through adolescence? Findings from an accelerated longitudinal Cohort study. J. Res. Pers. 2018, 74, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtackers, R. The relationship between attachment, the self-conscious emotions of shame and guilt & problem behavior in adolescents. MaRBLe Res. Pap. 2016, 6, 292–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gorrese, A. Peer Attachment and Youth Internalizing Problems: A Meta-Analysis. Child Youth Care Forum 2016, 45, 177–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Radin, R. Direct and interactive effects of peer attachment and grit on mitigating problem behaviors among urban left-behind adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Dou, K.; Yu, C.; Nie, Y.; Zheng, X. The Relationship between Peer Attachment and Aggressive Behavior among Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Effect of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy. Int. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, J.; Onckels, L.; Muris, P. Attachment Quality and Psychopathological Symptoms in Clinically Referred Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Early Maladaptive Schema. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2013, 22, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, K.; Demetriou, C.; Tricha, L.; Ioannou, M.; Georgiou, S.; Nikiforou, M.; Stavrinides, P. The effect of parental style on bullying and cyberbullying behaviors and the mediating role of peer attachment relationships: A longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. 2018, 64, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ran, G.; Li, B.; Liu, C.; Liu, G.; Luo, S.; Chen, W. Parental and peer attachment and adolescents’ behaviors: The mediating role of psychological suzhi in a longitudinal study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 83, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesurado, B.; Richaud, M.C. The relationship between parental variables, empathy and prosocial-flow with prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends, and family. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, P.W. Emotional competence and it’s influences on teaching and learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 22, 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P.S.Y.; Wu, F.K.Y. Emotional competence as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 975189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. What is emotional intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators, 1st ed.; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Caruso, D.R.; Salovey, P. The Ability Model of Emotional Intelligence: Principles and Updates. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarni, C. The Plasticity of Emotional Development. Emot. Rev. 2010, 2, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos-Sánchez, L.; Flujas-Contreras, J.M.; Gómez-Becerra, I. The role of emotional intelligence in psychological adjustment among adolescents. An. Psicol. 2017, 33, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baya, D.; Mendoza, R.; Paino, S.; Matos, M.G. Perceived emotional intelligence as a predictor of depressive symptoms during mid-adolescence: A two-year longitudinal study on gender differences. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V.; Mikolajczak, M.; Mavroveli, S.; Sánchez-Ruiz, M.J.; Furnham, A.; Pérez-González, J.C. Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, C.; Arguedas-Morales, M.; Marcos, R.; Martínez, M. Fortaleza psicológica adolescente: Relación con la inteligencia emocional y los valores. Aula Abierta 2020, 49, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.C.; Blair, B.L.; Buehler, C. Individual differences in adolescents’ emotional reactivity across relationship contexts. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Inglés, C.J.; Suriá, R.; Lagos, N.; Delgado, B.; Garvía-Fernández, J.M. Emotional intelligence profiles and self-concept in Chilean adolescents. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 40, 3860–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulou, M.S. How are trait emotional intelligence and social skills related to emotional and behavioural difficulties in adolescents? Educ. Psychol. 2014, 34, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Alcaide, R.; Extremera, N.; Pizarro, D. The role of emotional intelligence in anxiety and depression among adolescents. Individ. Differ. Res. 2006, 4, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeps, K.; Tamarit, A.; Postigo-Zegarra, S.; Montoya-Castilla, I. Los efectos a largo plazo de las competencias emocionales y la autoestima en los síntomas internalizantes en la adolescencia. Rev. Psicodidáct. 2021, 26, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yunkin, F.; Hardman, M.; Buchanan, B.; Nugent, N.; Pettus, M.; Lawrrence, B. The longitudinal relations between disciplinary practices and emotion regulation in early years. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 28, 860–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peachey, A.A.; Wenos, J.; Baller, S. Trait emotional intelligence related to bullying in elementary school children and to victimization in boys. OTJR 2017, 37, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomera, R.; Salguero, J.M.; Ruiz-Aranda, D. La percepción emocional como predictor estable del ajuste psicosocial en la adolescencia. Behav. Psychol./Psicol. Conduct. 2012, 20, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Parrish, C.; Zeman, J. Relations among saness regulation, peer acceptance, and social functioning in early adolescence: The role of gender. Soc. Dev. 2011, 20, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas Díaz, D.; Cabello, R.; Megías, A.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Systematic review and meta-analysis: The association between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-González, L.; Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Echezarraga, A. The role of emotional intelligence in the maintenance of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 127, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M. Conducta antisocial: Conexión con bullying/cyberbullying y estrategias de resolución de conflictos. Psychosoc. Interv. 2017, 26, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. The Strenghts and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. J. Child. Psych. 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Paíno, M.; Sastre, S.; Muñiz, J. Screening mental health problems during adolescence: Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J. Adolesc. 2015, 38, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.; Penelo, E.; Fornieles, A.; Brun-Gasca, C.; Olle, M. Factorial Structure and Internal Consistency of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment for Adolescents (IPPA) Spanish version. Univ. Psychol. 2016, 15, 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Takšic, V.; Mohorić, T.; Duran, M. Emotional skills and competence questionnaire (ESCQ) as a self-report measure of emotional intelligence. Horiz. Psychol. 2009, 18, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeps, K.; Tamarit, A.; Montoya-Castilla, I.; Takšic, V. Factorial structure and validity of the Emotional skills and competences Questionnaire (ESCQ) in Spanish adolescents. Behav. Psychol. Psicol. Conduct. 2019, 27, 275–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structural analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 28–74. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Mateu, D.; Alonso-Larza, L.; Gómez-Domínguez, M.T.; Prado-Gascó, V.; Valero-Moreno, S. I’m Not Good for Anything and That’s Why I’m Stressed: Analysis of the Effect of Self-Efficacy and Emotional Intelligence on Student Stress Using SEM and FSQCA. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, L.; Montoya-Castilla, I.; Prado-Gascó, V. The importance of trait emotional intelligence and feelings in the prediction of perceived and biological stress in adolescents: Hierarchical regressions and fsFSQCA models. Stress 2017, 20, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodside, A.G. Moving beyond multiple regression analysis to algorithms: Calling for adoption of a paradigm shift from symmetric to asymmetric thinking in data analysis and crafting theory. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry. Fuzzy Sets and Beyond, 1st ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eng, S.; Woodside, A.G. Configural analysis of the drinking man: Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analyses. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrovich, C.E.; Durlak, J.A.; Staley, K.C.; Weissberg, R.P. Social-Emotional Competence: An Essential Factor for Promoting Positive Adjustment and Reducing Risk in School Children. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.M.; Wojciak, A.S.; Cooley, M.E. Self-esteem: A mediator between peer relationships and behaviors of adolescents in foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 66, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, J.J.; Sánchez, P.A.; González, C.; Oriol, X.; Valenzuela, P.; Cabrera, T. Subjective Well-being, bullying, and school climate among Chilean adolescents over time. Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 13, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. The validity of the MSCEIT: Additional analyses and evidence. Emot. Rev. 2012, 4, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Range | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Attachment | |||||||||||

| 1. Trust T1 | 11–50 | 41.84 | 6.29 | - | |||||||

| 2. Communication T1 | 11–40 | 30.16 | 5.81 | 0.70 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. Alienation T1 | 6–30 | 16.36 | 4.06 | −0.44 ** | −0.23 ** | - | |||||

| Emotional competence | |||||||||||

| 4. Emotional perception T1 | 27–90 | 66.19 | 10.03 | 0.40 ** | 0.47 ** | −0.19 ** | - | ||||

| 5. Emotional expression T1 | 22–84 | 63.10 | 9.50 | 0.40 ** | 0.47 ** | −0.15 ** | 0.85 ** | - | |||

| 6. Emotional management T1 | 22–96 | 70.50 | 10.53 | 0.42 ** | 0.48 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.85 ** | 0.84 ** | - | ||

| Adjustment | |||||||||||

| 7. Emotional symptoms T2 | 5–15 | 8.08 | 2.23 | −0.20 ** | −0.09 * | 0.37 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.20 ** | - | |

| 8. Conduct problems T2 | 4–15 | 6.24 | 1.79 | −0.17 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.08 * | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.29 ** | - |

| 9. Peer problems T2 | 3–15 | 6.28 | 1.87 | −0.21 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.26 ** | 0.29 ** |

| Descriptive Statistics | Emot. Symp. | Cond. Prob. | Peer Prob. | Trust | Comm. | Alien. | Percep. | Express. | Manag. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 16.49 | 8.15 | 6.01 | 29,378.04 | 82,593.70 | 185.49 | 60,535.30 | 50,869.28 | 62,481.10 | |

| Standard deviation | 29.65 | 15.80 | 9.89 | 28,131.39 | 96,048.90 | 456.20 | 64,004.63 | 66,117.02 | 65,885.48 | |

| Minimum | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 8.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Maximum | 243.00 | 162.00 | 81.00 | 97,656.25 | 390,625.00 | 5000.00 | 279,936.00 | 279,936.00 | 279,936.00 | |

| Calibration values | ||||||||||

| Percentile | 10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1573.12 | 2707.20 | 4.00 | 5760.00 | 720.00 | 4320.00 |

| 50 | 6.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 19,531.25 | 46,080.00 | 48.00 | 40,000.00 | 24,000.00 | 40,000.00 | |

| 90 | 36.00 | 17.20 | 16.00 | 78,125.00 | 220,625.00 | 400.00 | 155,520.00 | 135,000.00 | 162,000.00 |

| Conditions | High Level of Emotional Symptoms (T2) | High Level of Conduct Problems (T2) | High Level of Peer Problems (T2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Trust (T1) | ● | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Communication (T1) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Alienation (T1) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Emotional perception (T1) | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| Emotional expression (T1) | ○ | ● | ● | ○ | ● | ||||

| Emotional management (T1) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ | |||

| Consistency | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.84 |

| Raw Coverage | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Unique Coverage | 0.018 | 0.025 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.014 | <0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Overall Solution Consistency | 0.41 | 0.24 | 0.51 | ||||||

| Overall Solution Coverage | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.80 | ||||||

| Conditions | Low Level of Emotional Symptoms (T2) | Low Level of Conduct Problems (T2) | Low Level of Peer Problems (T2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Trust (T1) | ● | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Communication (T1) | ○ | ● | ○ | ○ | |||||

| Alienation (T1) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||||

| Emotional perception (T1) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ||||

| Emotional expression (T1) | ● | ● | ● | ||||||

| Emotional management (T1) | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ○ | ||

| Consistency | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.85 |

| Raw Coverage | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.38 |

| Unique Coverage | 0.027 | 0.052 | 0.014 | <0.001 | 0.027 | 0.017 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.021 |

| Overall Solution Consistency | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.65 | ||||||

| Overall Solution Coverage | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.75 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Rodríguez, T.; De la Barrera, U.; Schoeps, K.; Valero-Moreno, S.; Montoya-Castilla, I. Longitudinal Analysis of Adolescent Adjustment: The Role of Attachment and Emotional Competence. Children 2022, 9, 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111711

Jiménez-Rodríguez T, De la Barrera U, Schoeps K, Valero-Moreno S, Montoya-Castilla I. Longitudinal Analysis of Adolescent Adjustment: The Role of Attachment and Emotional Competence. Children. 2022; 9(11):1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111711

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Rodríguez, Tamara, Usue De la Barrera, Konstanze Schoeps, Selene Valero-Moreno, and Inmaculada Montoya-Castilla. 2022. "Longitudinal Analysis of Adolescent Adjustment: The Role of Attachment and Emotional Competence" Children 9, no. 11: 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111711

APA StyleJiménez-Rodríguez, T., De la Barrera, U., Schoeps, K., Valero-Moreno, S., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2022). Longitudinal Analysis of Adolescent Adjustment: The Role of Attachment and Emotional Competence. Children, 9(11), 1711. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111711