Symptom and Illness Experience for English and Spanish-Speaking Children with Advanced Cancer: Child and Parent Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

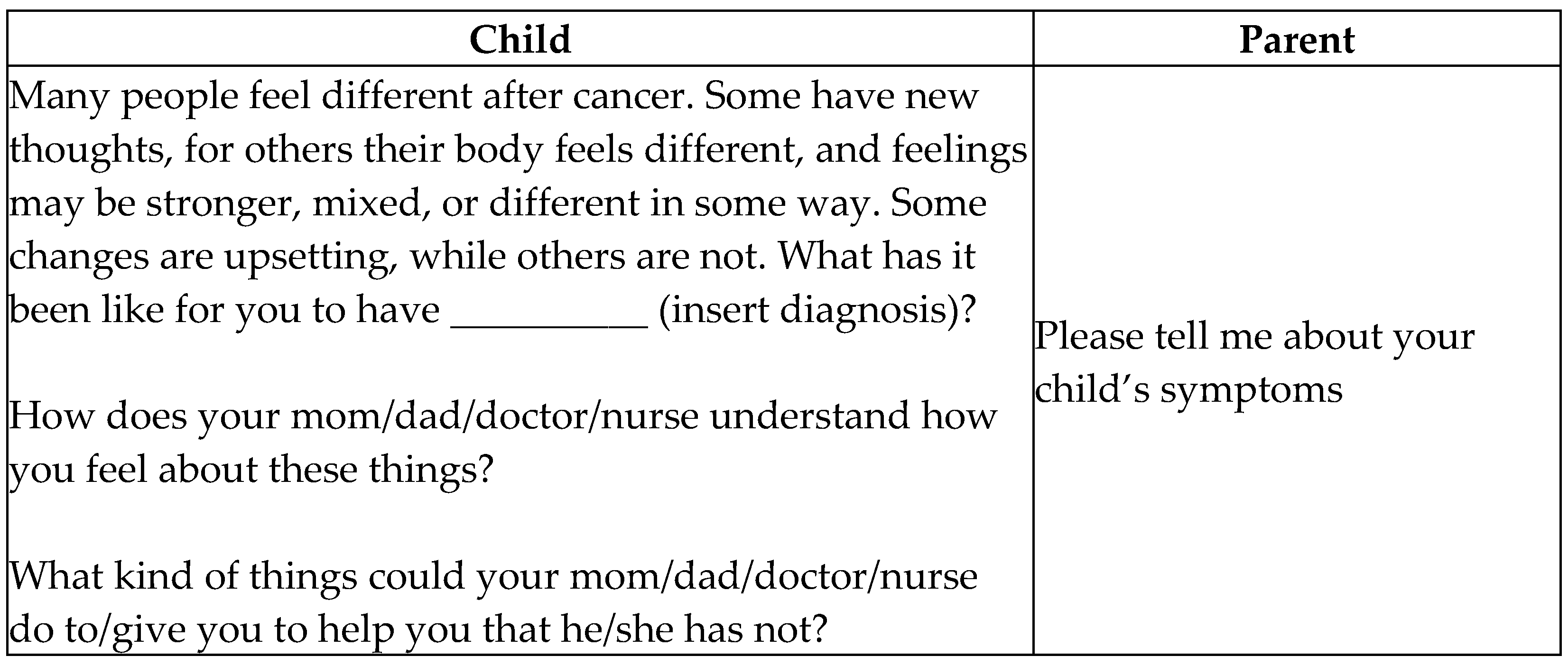

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenomenological Themes

3.2. Symptoms Disrupt Life

Path to Diagnosis

“She would wake up in the middle of the night and she would cry, she would scream, she would say her arm hurt, her leg hurt, she was tired, she slept all the time and she just wasn’t herself. And you know, and then you are telling them look, a child that wants attention doesn’t wake up at one o’clock in the morning screaming at the top of their lungs, that they are hurting. There is something wrong with them.”

“You know he started losing weight, appetite, which we just thought that was, he was a picky eater, he didn’t want to eat, but, you know, we look back now and we think, well, that was a sign; we just kind of ignored that … we didn’t realize that was one of the symptoms until we looked back …”

3.3. Life Is Disrupted

“OK, his major symptom is pain, obviously. Umm … back pain was his major symptom and leg pain … the point of that is it limited his walking, limited his activity … limited his playing with other kids … so it limited everything, really.”

“Well pain, as in headaches, no. But pain, as in of the heart.”

“It is just that he gets angry because he thinks … we overprotect him, right? But at the same time he gets sad because he wants to, like, for example … he was there at school, he likes American football a lot and he cannot [play].”

“Bad, sad. Because I cannot do anything … Well, like a normal child.” He also said, “Sometimes I am not myself; I am not the same person.”

3.4. Isolation

3.4.1. Lack of Understanding

3.4.2. Family Separations/Relationships

“Because he [dad] is always home trying to take care of my sister, and my momma has to stay out here with me so she can like be here to tell the doctor all the information cause dad’s home working trying to make money … I wish he would like come out here and stay with us until December, but he can’t cause he’s working and has to take care of my sister because she’s going to school.”

“He (brother) never knows who’s coming to get him from school, like today … I said we may or may not be home.”

3.5. Protection

“I am scared about him. They told me that he had hurt his backbone, fractured-so to also not let him run because one fall or something would hit him badly-harm him.”

“Well, he took it a little bad … he does not know how severe it is … because I have also not wanted to tell him because, well … the more sick [sic] he is going to get or get sad; I did not want that. He hardly asks anything.”

“I think he hides a lot. … He didn’t tell us how, how bad he was hurting cause [sic] he didn’t want to feel different, or to look at him different.”

3.6. Death Is Not for Children

“Well, when she started asking me questions about dying … You know, she could die from this. Just the thought of her, I mean, she didn’t want to die. You know, she knows, ‘I’m going to heaven, I know that, but I don’t want to die.’ Just stuff like that … You never want to try and take any kind of hope or anything away from them.”

“But she does not know, she does not know with full knowledge. Why? Because I think that I, as a mother, see that knowing certain things at times, instead of helping us, it can lead us to like “Why should I continue, why should I fight?’ Because like, what I feel like I am limiting her …”

“It’s either this or a blunt way to put it, it is six feet under.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, H.; Roberts, P.; Horgan, L. Association between self-report pain ratings of child and parent, child and nurse and parent and nurse dyads: Meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 63, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasagaram, U.; Taylor, D.M.; Braitberg, G.; Pearsell, J.P.; A Capp, B. Paediatric pain assessment: Differences between triage nurse, child and parent. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2009, 45, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.L.; Vowles, K.; Eccleston, C. Adolescent chronic pain-related functioning: Concordance and discordance of mother-proxy and self-report ratings. Eur. J. Pain 2010, 14, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinds, P.S.; Hockenberry-Eaton, M. Developing a research program on fatigue in children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2001, 18, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marcus, K.L.; Santos, G.; Ciapponi, A.; Comandé, D.; Bilodeau, M.; Wolfe, J.; Dussel, V. Impact of Specialized Pediatric Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 59, 339–364.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widger, K.; Medeiros, C.; Trenholm, M.; Zuniga-Villanueva, G.; Streuli, J.C. Indicators Used to Assess the Impact of Specialized Pediatric Palliative Care: A Scoping Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedel, M.; Aujoulat, I.; Dubois, A.-C.; Degryse, J.-M. Instruments to Measure Outcomes in Pediatric Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Podiatrics 2018, 143, e20182379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hui, D.; dos Santos, R.; Chisholm, G.B.; Bruera, E. Symptom Expression in the Last Seven Days of Life Among Cancer Patients Admitted to Acute Palliative Care Units. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 50, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niksic, M.; Rachet, B.; Warburton, F.G.; Forbes, L.J.L. Ethnic differences in cancer symptom awareness and barriers to seeking medical help in England. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Mercado, V.J.; Faan, P.D.W.; Mpa, A.R.W.M.; Pharm-D, E.P.; Colon, G. The symptom experiences of Puerto Rican children undergoing cancer treatments and alleviation practices as reported by their mothers. Int. J. Nurs. Pr. 2016, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhukovsky, D.S.; Rozmus, C.L.; Robert, R.S.; Bruera, E.; Wells, R.J.; Ms, G.B.C.; Allo, J.A.; Cohen, M.Z. Symptom profiles in children with advanced cancer: Patient, family caregiver, and oncologist ratings. Cancer 2015, 121, 4080–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.Z.; Kahn, D.L.; Steeves, R.H. Hermeneutic Phenomenological Research: A Practical Guide for Nurse Researchers; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L. Feeling states: A new approach to understanding how children and adolescents with cancer experience symptoms. Cancer Nurs. 2008, 31, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Degner, L.F.; Yanofsky, R. A different perspective to approaching cancer symptoms in children. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2003, 26, 800–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, R.; Zhukovsky, N.S.; Mauricio, R.; Gilmore, K.; Morrison, S.; Palos, G.R. Bereaved Parents’ Perspectives on Pediatric Palliative Care. J. Soc. Work End-of-Life Palliat. Care 2012, 8, 316–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, K.E.; Vos, K.; Raybin, J.L.; Ward, J.; Balian, C.; Gilger, E.A.; Li, Z. Comparison of child self-report and parent proxy-report of symptoms: Results from a longitudinal symptom assessment study of children with advanced cancer. J. Spéc. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 26, e12316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, J.W.; McFatrich, M.; Withycombe, J.S.; Maurer, S.; Jacobs, S.S.; Lin, L.; Lucas, N.R.; Baker, J.N.; Mann, C.M.; Sung, L.; et al. Agreement Between Child Self-report and Caregiver-Proxy Report for Symptoms and Functioning of Children Undergoing Cancer Treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e202861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sourkes, A. Illness and Treatment, in Armfuls of Time; Sourkes, B.M., Ed.; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1995; pp. 31–81. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, J.; Mc Kenna, H.P.; Fitzsimons, D.; Mc Cance, T.V. An exploration of the experience of cancer cachexia: What patients and their families want from healthcare professionals. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2009, 19, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Median Years of Age (Range) | 11 (7–17) |

| Gender: Male/Female | 7/3 |

| Race: White/Hispanic | 4/6 |

| Language of interview: English/Spanish | 7/3 |

| Primary Diagnosis | |

| CNS tumor | 3 |

| Leukemia | 3 |

| Lymphoma | 1 |

| Sarcoma | 3 |

| Extent of Disease | |

| Metastatic | 5 |

| Progressive | 1 |

| Recurrent | 4 |

| Median Years of Age (Range) | 43.5 (27–52) |

| Gender: Male/Female | 1/9 |

| Race: White/Hispanic | 4/6 |

| Education | |

| 9th–12th grade | 2 |

| Some college or technical | 4 |

| College graduate | 2 |

| Graduate school | 2 |

| Annual Income | |

| $24,999 or less | 3 |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 4 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 2 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 1 |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 5 |

| Single/Never married | 3 |

| Single/Lives with partner | 1 |

| Divorced | 1 |

Physical and Psychological Symptoms

|

Interpersonal Implications

|

Communication Problems

|

| Anticipatory Grief |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhukovsky, D.S.; Rozmus, C.L.; Robert, R.; Bruera, E.; Wells, R.J.; Cohen, M.Z. Symptom and Illness Experience for English and Spanish-Speaking Children with Advanced Cancer: Child and Parent Perspective. Children 2021, 8, 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8080657

Zhukovsky DS, Rozmus CL, Robert R, Bruera E, Wells RJ, Cohen MZ. Symptom and Illness Experience for English and Spanish-Speaking Children with Advanced Cancer: Child and Parent Perspective. Children. 2021; 8(8):657. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8080657

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhukovsky, Donna S., Cathy L. Rozmus, Rhonda Robert, Eduardo Bruera, Robert J. Wells, and Marlene Z. Cohen. 2021. "Symptom and Illness Experience for English and Spanish-Speaking Children with Advanced Cancer: Child and Parent Perspective" Children 8, no. 8: 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8080657

APA StyleZhukovsky, D. S., Rozmus, C. L., Robert, R., Bruera, E., Wells, R. J., & Cohen, M. Z. (2021). Symptom and Illness Experience for English and Spanish-Speaking Children with Advanced Cancer: Child and Parent Perspective. Children, 8(8), 657. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8080657