Impact of Sports Education Model in Physical Education on Students’ Motivation: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

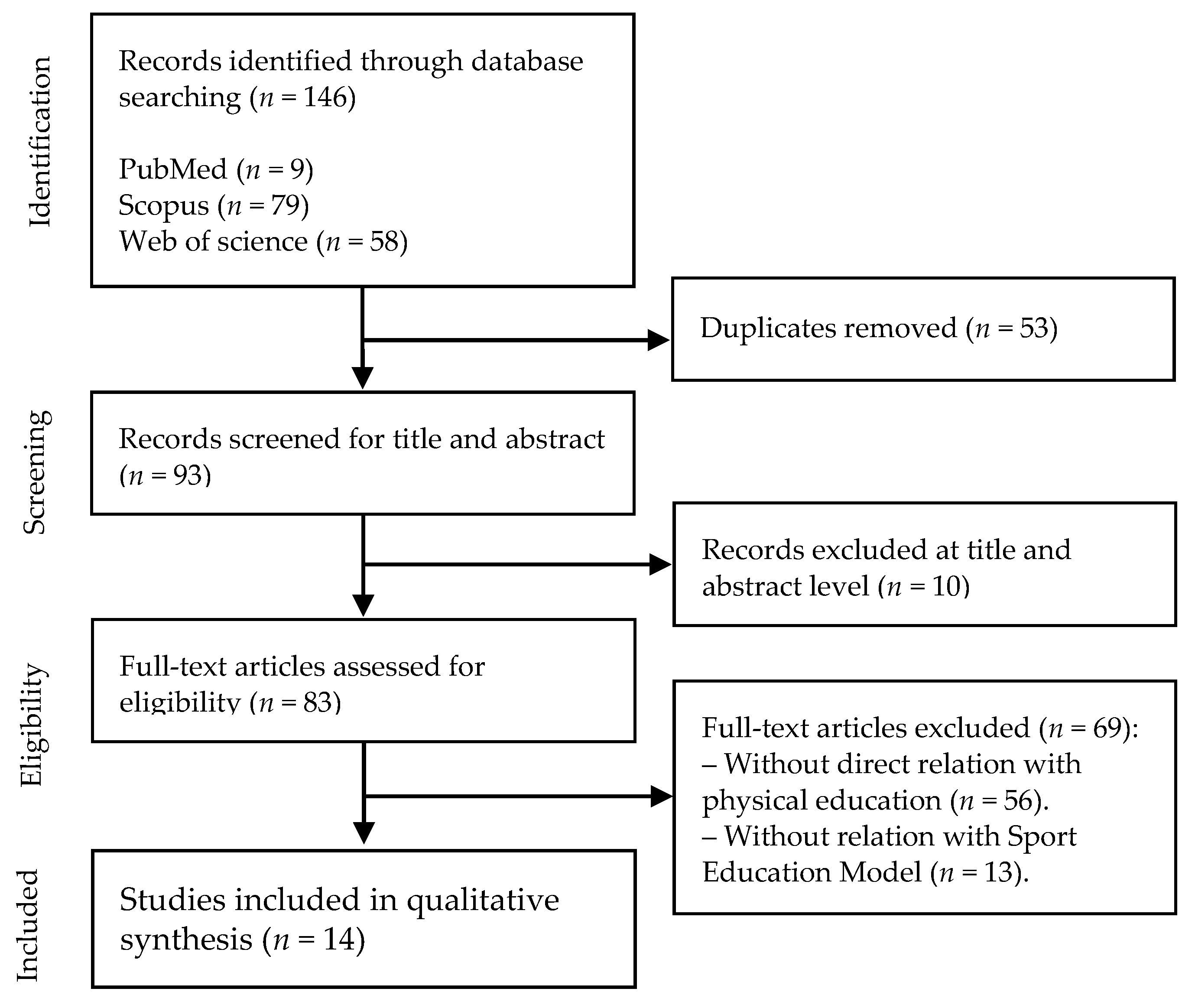

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Articles and Study Background

3.2. Participants and Setting

3.3. Program Design and Implementation

3.4. Main Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siedentop, D. Sport Education: Quality PE through Positive Sport Experiences; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 1994; p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- Siedentop, D.; Hastie, P.; Van der Mars, H. Complete Guide to Sport Education, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2011; p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A. A Theoretical Conceptualization for Motivation Research in Physical Education: An Integrated Perspective. Quest 2001, 53, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S. Relationships between Perceived Learning Environment and Intrinsic Motivation in Middle School Physical Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1996, 15, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoumanis, N. A self-determination approach to the understanding of motivation in physical education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 71, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L.; Tuson, K.; Fortier, M.; Vallerand, R.; Briére, N.; Blais, M. Toward a New Measure of Intrinsic Motivation, Extrinsic Motivation, and Amotivation in Sports: The Sport Motivation Scale (SMS). J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1995, 17, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, K.; Deci, E.; Ryan, R. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Contemp. Sociol. 1988, 17, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Giménez, A.; Fernández-Río, J.; Méndez-Alonso, D. Sport education model versus traditional model: Effects on motivation and sportsmanship. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Fis. Deporte 2015, 15, 449–466. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, C.C.; Luo, Y.J. The influence of low-performing students’ motivation on selecting courses from the perspective of the sport education model. Phys. Educ. Stud. 2019, 23, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, D. Change in Affect and Needs Satisfaction for Amotivated Students within the Sport Education Model. J. Teach. Phys. Educa. 2010, 29, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassandra, M.; Goudas, M.; Chroni, S. Examining factors associated with intrinsic motivation in physical education: A qualitative approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Maxera, F.; Méndez-Giménez, A.; de Oieda, D.M. Sport education model and roles’ dynamics. Effects of an intervention on motivational variables of elementary schools’ students. Cult. Cienc. Deporte 2018, 13, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallhead, T.L.; Ntoumanis, N. Effects of a sport education intervention on students’ motivational responses in physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2004, 23, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño, R.; Cueto-Martín, B.; Morales-Ortiz, E.; Medina-Casaubón, J. Influence of sport education on high school students’ motivational response: A gender perspective. Retos 2020, 37, 546–555. [Google Scholar]

- García-González, L.; Abós, Á.; Diloy-Peña, S.; Gil-Arias, A.; Sevil-Serrano, J. Can a hybrid sport education/teaching games for understanding volleyball unit be more effective in less motivated students? An examination into a set of motivation-related variables. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuevas, R.; García-López, L.M.; Serra-Olivares, J. Sport education model and self-determination theory: An intervention in secondary school children. Kinesiology 2016, 48, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, C.; Gao, R.; Xu, S. Impact of a sport education season on students’ table tennis skills and attitudes in China’s high school. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2019, 9, 820–825. [Google Scholar]

- Burgueño, R.; Medina-Casaubón, J.; Morales-Ortiz, E.; Cueto-Martín, B.; Sánchez-Gallardo, I. Educación Deportiva versus Enseñanza Tradicional: Influencia sobre la regulación motivacional en alumnado de Bachillerato. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2017, 17, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Arias, A.; Harvey, S.; Cárceles, A.; Práxedes, A.; Del Villar, F. Impact of a hybrid TGfU-Sport Education unit on student motivation in physical education. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179876. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Casaubón, J.; Burgueño, R. Influencia de una temporada de educación deportiva sobre las estrategias motivacionales en alumnado de bachillerato: Una visión desde la teoría de la auto-determinación. Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2017, 13, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wallhead, T.L.; Garn, A.C.; Vidoni, C. Effect of a sport education program on motivation for physical education and leisure-time physical activity. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2014, 85, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.M.; Sum, K.W.R.; Leung, F.L.E.; Wallhead, T.; Morgan, K.; Milton, D.; Ha, S.C.A.; Sit, H.P.C. Effect of sport education on students’ perceived physical literacy, motivation, and physical activity levels in university required physical education: A cluster-randomized trial. High. Educ. 2020, 6, 1137–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Arias, A.; Harvey, S.; García-Herreros, F.; González-Víllora, S.; Práxedes, A.; Moreno, A. Effect of a hybrid teaching games for understanding/sport education unit on elementary students’ self-determined motivation in physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 27, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallhead, T.L.; Garn, A.C.; Vidoni, C. Sport Education and social goals in physical education: Relationships with enjoyment, relatedness, and leisure-time physical activity. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2013, 18, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, A.; Wallhead, T.; Readdy, T. Exploring the Synergy Between Sport Education and In-School Sport Participation. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2018, 37, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, D.; Goc Karp, G. A self-determined perspective of the Sport Education Model. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2010, 15, 401–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smither, K.; Xihe, Z. High school students’ experiences in a Sport Education unit: The importance of team autonomy and problem-solving opportunities. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2011, 17, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, M.; Durden-Myers, E.; Pot, N. The Value of Fostering Physical Literacy. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2018, 37, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pill, S. A teacher’s perceptions of the sport education model as an alternative for upper primary school physical education. ACHPER Aust. Healthy Lifestyles J. 2008, 55, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

| Source | Country | Study Design, Sample Characteristics (n, Sex, Age), Recruitment | Sport Education Model Experience | Data Assessment (Instruments to Assess Motivation) | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burgueño, Medina-Casaubón, Morales-Ortiz, Cueto-Martín and Sánchez-Gallardo [20] | Spain | Quasi-experimental study. Pre-and post-test measures and intra- and inter-group analysis. 44 high school students (22 boys, Mage = 16.32 ± 0.57). | Following the structural guidelines of the SEM established by Siedentop et al. (2011) for 12 sessions of basketball teaching. | Situational Motivation Scale. | The SEM significantly improved the level of intrinsic motivation and identified regulation about TEM. SE has significantly reduced external regulation and amotivation in students regarding TTM. |

| Burgueño, Cueto-Martín, Morales-Ortiz and Medina-Casaubón [15] | Spain | Pre-experimental pre-/post-test design. 75 high school students (38 boys, Mage = 16.75 ± 0.87). | The intervention programme under SE conditions included 3 classes, twelve 50-min lessons each, twice per week in regular PE schedule. Based on the preference of the three PE teachers, indoor soccer, volleyball and basketball were taught. | Perceived Locus of Causality Scale. Achievement Goal Questionnaire-Physical Education (Spanish version). Social Goal Scale Physical Education (Spanish version). | The SEM was a pedagogical model that favours the adequate motivational response of high school students in terms of self-determination, motivational achievement, and social motivation in the sports teaching-learning process in PE classes. |

| Chenchen, Rong and Shuaijing [19] | China | Study with nonequivalent pre-test–post-test. Two groups: IG (the SEM group) n = 36 and CG (traditional sport Model) n = 28; Aged 16–17 years old from a senior high school in China. | Students participated in one lesson per week for 16 weeks in a semester, and each lesson should last for 40 min of table tennis classes taught following the SEM. | Questionnaire of student’s attitude and interviews. | The learning attitudes of students in SE class including cognitive, emotional, and behaviour disposition improved significantly after the season. |

| Choi, Sum, Leung, Wallhead, Morgan, Milton, Ha and Sit [24] | China, Hong Kong | A Cluster-randomised study design. 372 participants. Two groups: IG (the SEM group) n = 188 and CG n = 184. Mage 18.5 years. 95% of the study sample were Chinese. 70% of the study sample were male. | SE seasons were designed for badminton, basketball, football handball, physical conditioning, swimming, and volleyball. Each SE season included ten 90-min lessons, 1-day per week. | Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Physical activity enjoyment scale (PACES). Empowering and disempowering motivational climate questionnaire in PE (EDMCQ—PE). | The SE group presented higher scores in the internalised regulations of intrinsic and identified regulation motivations. They also had lower scores in external and amotive regulations. |

| Cuevas, García-López and Serra-Olivares [18] | Spain | Quasi-experimental design. Two groups: IG (the SEM group) n = 43; and CG (traditional PE lessons) n = 43. 86 PE students (49 girls) between 15 and 17 years of age (Mage = 15.65; SD = 0.78). | The teaching unit on volleyball consisted of 19 55-min sessions (two/week in the regular PE schedule) structured based on the SEM. | Questionnaire for Evaluating Motivation in Physical Education (CMEF). Sport Satisfaction Instrument (SSI). Intention to be Physically Active Scale (IPAS). | The results showed improvements in intrinsic motivation in the SEM intervention group. |

| García-González, Abós, Diloy-Peña, Gil-Arias and Sevil-Serrano [16] | Spain | Pre-experimental pre-/post-test design. A final sample of 49 students, Mage = 15.5 ± 0.57, 49% female from secondary education level. | A hybrid SE/TGfU volleyball teaching unit was applied twice per week over five weeks (10 lessons of 50 min). | The Basic Psychological Needs Support Questionnaire in PE. Basic Psychological Need in Exercise Scale (BPNES). Novelty Need Satisfaction Scale (NNSS). Perceived Variety in Exercise questionnaire (PVE). | This hybrid SE/TGfU could improve the students’ motivation during the PE classes, particularly those who showed an early low or moderate self-determined motivation at the beginning of the intervention. This model could bring more positive experiences to the students and be more inclusive. |

| Gil-Arias, Harvey, Cárceles, Práxedes and Del Villar [21] | Spain | A crossover design was utilised, using the technique of counterbalancing. 55 students (Mage = 15.45 ± 0.41, min. 27 females from Secondary Education school. | The intervention was conducted over eight weeks (two months) for a total of 16 lessons and focused on the team sports of volleyball and ultimate frisbee. One group experienced a hybrid SE/TGfU unit, followed by a unit of direct instruction. A second group had the units in the opposite order. | Perceived Locus of Causality. Basic Psychological Needs in Exercise Scale. Enjoyment in Sport Scale. The intention to be physically active scale was administered to participants. | A hybrid model of TGfU/SE stimulated increases in autonomy, relatedness, competence, autonomous motivation, enjoyment, and intention to be more active compared to direct instruction. |

| Gil-Arias, Harvey, García-Herreros, González-Víllora, Práxedes and Moreno [25] | Spain | Pre-intervention/post-intervention quasi-experimental design. IG (the SEM group) n = 148; Mage = 10.39 ± 0.48, 71 females; G (direct instruction) n = 144; Mage = 10.43 ± 0.49, 69 females. Students were in their fifth year of elementary school | A hybrid SE/TGfU basketball teaching unit was conducted during 16 lessons (8 weeks), 50 min twice a week. | Perceived Locus of Causality Questionnaire. PA Class Satisfaction Questionnaire. Autonomy-Supportive Coaching Strategies Questionnaire. BPNs in exercise scale. Relationship goals questionnaire-friendship version. | A hybrid TGfU/SE unit encouraged an autonomy-supportive, inclusive, and equitable PE learning environment. All students have chances to increase their commitment, enjoyment, and social interactions within PE lessons. |

| Kao and Luo [9] | Taiwan, China | Quasi-experimental design. IG (the SEM group) n = 59; Mage = 21.42 ± 0.75, 32 men; CG (direct instruction) n = 56; Mage = 21.38 ± 0.73, 29 men. | A SE-based badminton teaching unit was conducted over 10 weeks. | Elective Motivation Scale of Physical Education Curriculum (EMSPEC). | Students’ elective motivation toward PE improved and was higher than those who received direct instruction. The SEM also increased the elective motivation of low-performing students. |

| Medina-Casaubón and Burgueño [22] | Spain | Quasi-experimental design. 44 students (22 girls, Mage 16.32 ± 0.57). IG (the SEM group) n = 22; CG (traditional teaching group) n = 22. | A SE basketball teaching unit was conducted for 12 lessons of 55 min. | The Questionnaire to Support Basic Psychological Needs in Physical Education. | the SEM improved the perceived level of autonomy support and structure in the inter-group analysis and the intra-group. |

| Méndez-Giménez, Fernández-Río and Méndez-Alonso [8] | Spain | Quasi-experimental design with three levels of treatment: (1) Traditional model = 110, (3) SE- with conventional resources: N = 107, and (3) SE- with self-made materials: N = 78. In total 295 students (159 males), Mage = 14.2 ± 1.68. Participants belonged to different class groups from 7th to 11th grade | A SE Ultimate-Frisbee learning unit of 12 sessions of 50 min each. Two SE approaches were considered: (1) SE with conventional resources and (2) SE with self-made materials. | Achievement Goal Questionnaire-Physical Education (AGQ-PE). Friendship Goals in Physical Education Questionnaire. Basic Psychological Needs in Exercise Scale (BPNES). | Both the SEM groups reported improvements over time in autonomy, competence, and relatedness to others, versus the only improvement in autonomy in the traditional model. The SEM was shown to be more effective than the traditional method at the motivational and attitudinal levels. |

| Puente-Maxera, Méndez-Giménez and de Oieda [13] | Spain | Quasi-experimental, pre-test, and post-test measures study. 36 students (17 women; mean age 11.36 ± 0.59). Participants belonged to elementary school | A SE handball teaching unit of 10 sessions of 60 min each. | Motivation Orientation (GOES). Climate Motivation (CMI). Basic Psychological needs satisfaction (EMMD). Interviews. | the SEM produced an oriented climate to the task. Dynamic roles were shown as a powerful methodological strategy for students’ motivation. |

| Wallhead and Ntoumanis [14] | England | Non-equivalent control group (IG (the SEM) n = 25; CG= (traditional teaching approach), n = 26. In total, 51 boys (46 Caucasians and 5 Asian descent; Mage 14.3 ± 0.48). | 8-week intervention of SE basketball teaching unit. | Enjoyment, Effort, and Perceived Competence (IMI). Achievement goal orientations (TEOSQ). Perceived Autonomy (ASRQ). Perceptions of motivational climate (LAPOPECQ). | Students in the SEM had significantly higher post-intervention enjoyment and perceived effort than those taught with the traditional PE approach. |

| Wallhead, Garn and Vidoni [23] | United States, Midwestern | Non-equivalent control-group design (IG = the SEM approach; CG = multi-activity model of instruction). 568 students from 2 high schools (310 girls; Mage 14.75 ± 0.48; ethnic minority students 20%-30%). | Four 25-lesson seasons of floor hockey, volleyball, team handball, and basketball were taught using the SE approach. | Perceived Locus of Causality Questionnaire (PLCQ). Academic Motivation Scale (AMS). Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI). | The SEM group reported greater increases in perceived effort and enjoyment of the program than the students taught within the multi-activity model. Those positive affective outcomes were enabled by the development of more autonomous forms of motivation. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tendinha, R.; Alves, M.D.; Freitas, T.; Appleton, G.; Gonçalves, L.; Ihle, A.; Gouveia, É.R.; Marques, A. Impact of Sports Education Model in Physical Education on Students’ Motivation: A Systematic Review. Children 2021, 8, 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8070588

Tendinha R, Alves MD, Freitas T, Appleton G, Gonçalves L, Ihle A, Gouveia ÉR, Marques A. Impact of Sports Education Model in Physical Education on Students’ Motivation: A Systematic Review. Children. 2021; 8(7):588. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8070588

Chicago/Turabian StyleTendinha, Ricardo, Madalena D. Alves, Tiago Freitas, Gonçalo Appleton, Leonor Gonçalves, Andreas Ihle, Élvio R. Gouveia, and Adilson Marques. 2021. "Impact of Sports Education Model in Physical Education on Students’ Motivation: A Systematic Review" Children 8, no. 7: 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8070588

APA StyleTendinha, R., Alves, M. D., Freitas, T., Appleton, G., Gonçalves, L., Ihle, A., Gouveia, É. R., & Marques, A. (2021). Impact of Sports Education Model in Physical Education on Students’ Motivation: A Systematic Review. Children, 8(7), 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8070588