Getting to Hope: Perspectives from Patients and Caregivers Living with Chronic Childhood Illness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

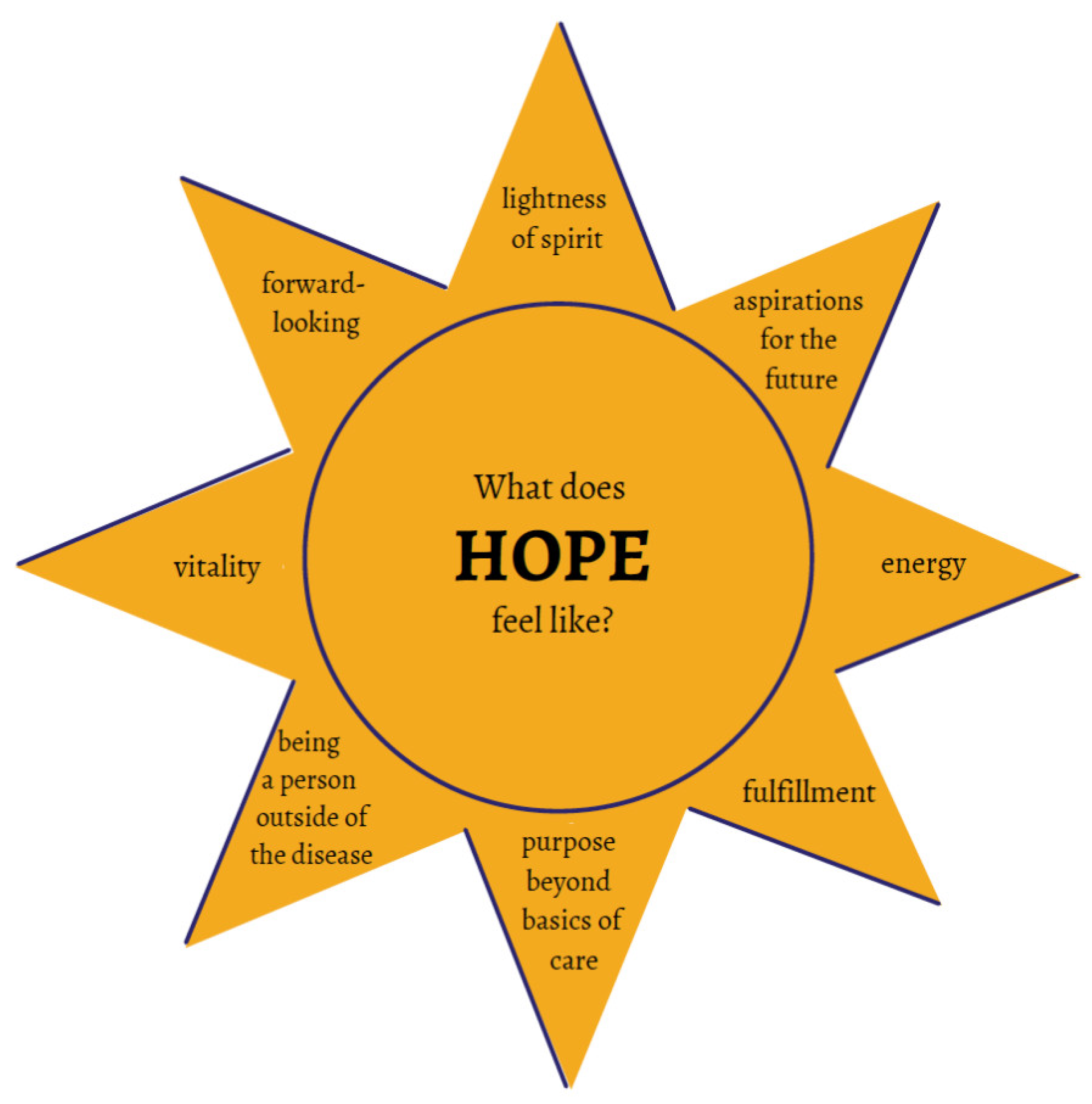

3.1. The Idea of Hope

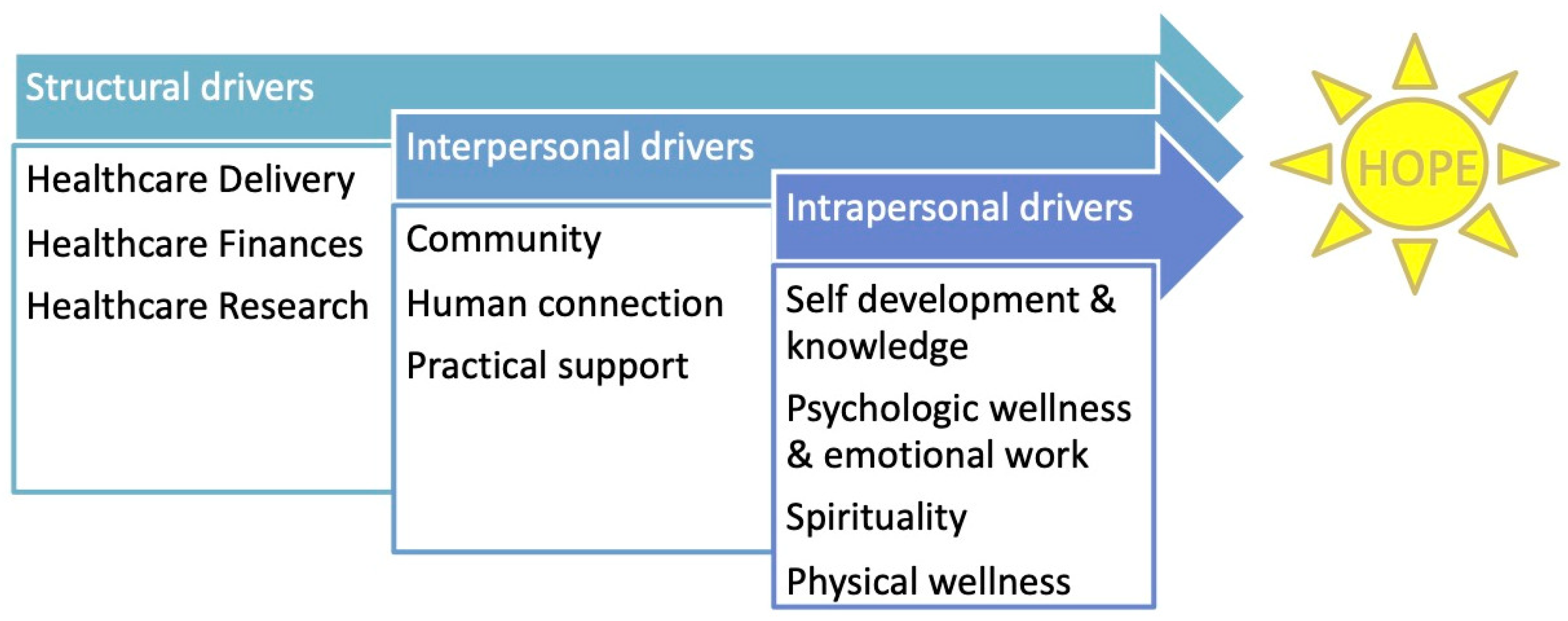

3.2. Promoters and Inhibitors of Hope

4. Discussion

4.1. Defining Hope

4.2. Conceptual Models of Hope

4.3. Hope Research

4.4. Hope in Healthcare

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perrin, J.M.; Bloom, S.R.; Gortmaker, L.S. The increase of childhood chronic conditions in the United States. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 297, 2755–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Veen, W. The small epidemiologic transition: Further decrease in infant mortality due to medical intervention during pregnancy and childbirth, yet no decrease in childhood disabilities. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2003, 147, 378–381. [Google Scholar]

- von Scheven, E.; Nahal, B.K.; Cohen, I.C.; Kelekian, R.; Franck, L.S. Research Questions that Matter to Us: Priorities of young people with chronic illnesses and their caregivers. Pediatr. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.F. Hope: A construct central to nursing. Nurs. Forum 2007, 42, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.O. An Analysis of the Concept of Hope in the Adolescent With Cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 1997, 14, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, P.S. Adolescent hopefulness in illness and health. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1998, 10, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M.; Doberneck, B. Delineating the Concept of Hope. Image J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 1995, 27, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venning, A.; Eliott, J.; Wilson, A.; Kettler, L. Understanding young peoples’ experience of chronic illness: A systematic review. Int. J. Evid. Based. Healthc. 2008, 6, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griggs, S.; Walker, R.K. The Role of Hope for Adolescents with a Chronic Illness: An Integrative Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faith, M.A.; Mayes, S.; Pratt, C.D.; Carter, C. Improvements in Hope and Beliefs about Illness Following a Summer Camp for Youth with Chronic Illnesses. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 44, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.C.A.B.; Garcia-Vivar, C.; Neris, R.R.; Alvarenga, W.d.; Nascimento, L.C. The experience of hope in families of children and adolescents living with chronic illness: A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 3246–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, R.E.K.; Bauman, L.J.; Westbrook, L.E.; Coupey, S.M.; Ireys, H.T. Framework for identifying children who have chronic conditions: The case for a new definition. J. Pediatr. 1993, 122, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhart, A.; Slogeris, B.; Sadreameli, S.C.; Jassal, M.S. Using a human-centered design approach for collaborative decision-making in pediatric asthma care. Public Health 2019, 170, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, M.; Huang, T.T.K.; Breland, J.Y. Design thinking in health care. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2018, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Franck, L.S.; McLemore, M.R.; Cooper, N.; De Castro, B.; Gordon, A.Y.; Williams, S.; Williams, S.; Rand, L. A novel method for involving women of color at high risk for preterm birth in research priority setting. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 131, 56220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotland, E. The Psychology of Hope; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, C.R.; Harris, C.; Anderson, J.R.; Holleran, S.A. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farran, C.J.; Popovich, J.M. Hope: A relevant concept for geriatric psychiatry. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1990, 4, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, L.; Moore, D.; Nunns, M.; Thompson Coon, J.; Ford, T.; Berry, V.; Garside, R. Experiences of interventions aiming to improve the mental health and well-being of children and young people with a long-term physical condition: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 832–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eunice, D.Y.; Cynthia, P.; Barry, S.; Susan, D.; Jonathan, D.; Kamilah, J.; John, S.; Theodore, S. Accentuate the Positive: Strengths-Based Therapy for Adolescents. Adolesc. Psychiatry (Hilversum) 2020, 10, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Steen, T.A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 1985, 147, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikocka-Walus, A.; Stokes, M.; Evans, S.; Olive, L.; Westrupp, E. Finding the power within and without: How can we strengthen resilience against symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression in Australian parents during the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 145, 110433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Lewensohn, O.; Abu-Kaf, S.; Kalagy, T. Hope and Resilience During a Pandemic Among Three Cultural Groups in Israel: The Second Wave of Covid-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bethell, C.; Jones, J.; Gombojav, N.; Linkenbach, J.; Sege, R. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample: Associations Across Adverse Childhood Experiences Levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, D.; Yang, C.; Johnson, K.; Linkenbach, J.; Sege, R. Transforming Practice with HOPE (Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences). Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landes, S.J.; Mcbain, S.A.; Curran, G.M. An Introduction to Effectiveness-Implementation Hybrid Designs. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 280, 112513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Trevena, L. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijngaarde, R.O.; Hein, I.; Daams, J.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Ubbink, D.T. Chronically ill children’s participation and health outcomes in shared decision-making: A scoping review. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Activity | Discussion Prompts |

|---|---|

| Focus group #1 |

|

| Focus group #2 |

|

| Focus group #3 |

|

| Focus group #4 |

|

| Focus group #5 |

|

| Focus group #6 |

|

| Focus group #7 |

|

| Focus group #8 |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

von Scheven, E.; Nahal, B.K.; Kelekian, R.; Frenzel, C.; Vanderpoel, V.; Franck, L.S. Getting to Hope: Perspectives from Patients and Caregivers Living with Chronic Childhood Illness. Children 2021, 8, 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060525

von Scheven E, Nahal BK, Kelekian R, Frenzel C, Vanderpoel V, Franck LS. Getting to Hope: Perspectives from Patients and Caregivers Living with Chronic Childhood Illness. Children. 2021; 8(6):525. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060525

Chicago/Turabian Stylevon Scheven, Emily, Bhupinder K. Nahal, Rosa Kelekian, Christina Frenzel, Victoria Vanderpoel, and Linda S. Franck. 2021. "Getting to Hope: Perspectives from Patients and Caregivers Living with Chronic Childhood Illness" Children 8, no. 6: 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060525

APA Stylevon Scheven, E., Nahal, B. K., Kelekian, R., Frenzel, C., Vanderpoel, V., & Franck, L. S. (2021). Getting to Hope: Perspectives from Patients and Caregivers Living with Chronic Childhood Illness. Children, 8(6), 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060525