Abstract

The importance of family functioning in the development of child and adult psychopathology has been widely studied. However, the relationship between partners’ adjustment and family health is less studied. This paper aims to describe and summarize research that analyzes the relationship between partners’ adjustment and family health. A systematic review was conducted in the PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Lilacs, Psicodoc, Cinahl, and Jstor databases. Inclusion criteria were as follows: articles published from 2012 to 2019 in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Data were extracted and organized according to the family health model: family climate, integrity, functioning, and coping. Initially, 835 references were identified, and 24 articles were assessed for quality appraisal. Finally, 20 publications were selected. Results showed that couple adjustment was an important factor that triggered the emotional climate of the family, was positively intercorrelated to parenting alliance or coparenting, and contributed to family efficacy and help when facing stressful life events. Findings revealed a consensus about the relationship between couple dyadic adjustment and family health. The results could orientate interventions to promote well-being and to increase quality of life and family strength. Health professionals should thoroughly study couple relationships to identify risk factors, assess family skills, and promote family health.

1. Introduction

The focus of health care was recently oriented to families [1]. This approach supposed a tactical and strategical change in the practice of health professionals. In order to achieve this new approach, it has been necessary to take into account a conceptual, theoretical, and instrumental framework, to describe the reality of families [1]. In this sense, the family is the smallest social unit, and it is considered as the main and fundamental basis of any society. It is the core of socialization, education, and optimum biopsychosocial development of its members. Family provides the context where values are transmitted, ideas are learned and adopted, and beliefs and norms of conduct are acquired [2]. Family is considered a group of two or more people coexisting as a spiritual, cultural, and socio-economic unit. Even without physical coexistence, they share psycho-emotional and material needs and common objectives and interests [3].

Traditionally, Family System Theory has been considered the theoretical framework in family research [1]. According to this theory, a family is an open system with relationship patterns at individual, dyadic, and systemic levels, with interconnectedness among the various levels. It comprises three primary subsystems (marital, parental, and sibling) that are delineated by boundaries and rules connected to themselves, which affect, and are reciprocally affected, by each other [4]. Each subsystem contributes to family functioning through an exercise of roles and tasks that are necessary for the whole system [2].

Family health is considered a complex concept, a multidimensional, interactive holistic phenomenon that includes the biological, psychological, spiritual, sociological, and culture factors of individual members and the whole family system [5]. Family health is the family capacity to function effectively as a biopsychosocial unit, meeting the needs of its members and contributing to their development. It is a dynamic process that requires an optimal social climate and family integrity, good family functioning, and a level of resistance and coping that allows the family to deal with crisis situations [6]. Lima-Rodríguez et al. [6,7] proposed a model of family comprised of five dimensions: climate, integrity, functioning, resilience, and coping, which are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dimensions of family health.

Within the family system, research has identified the couple subsystem as the principal and fundamental one for the development of family members and the maintenance of family health [8,9]. The couple dyadic adjustment has traditionally been related to health and well-being and couple dyadic maladjustment has been related to disease [10]. Greater marital quality has been related to better health, including lower risk of mortality and lower cardiovascular reactivity during marital conflict [11]. This approach has been the basis for relating the criteria of well-being or couple distress with welfare or discomfort in family health [10]. Previous studies have identified a positive link between the quality of the marital relationship and the relationship they establish with their children [12]. Parental conflict influences the children emotionally, physiologically, cognitively, and behaviorally in regard to their growth, and it has an impact on their development and mental health over time [13]. Interparental conflict also affects their parenting behaviors, particularly harsh discipline and parental acceptance [14]. So, it is essential that the couple subsystem has a good dyadic adjustment for the maintenance of family health. Recent literature suggests interventions based on the quality of the significant others’ relationship to promote family functioning are needed [15].

The quality of the relationship or the couple dyadic adjustment are indicators of the health of the couple. Couple dyadic adjustment represents the degree to which couples are satisfied with their relationship in domains such as cohesion, satisfaction, consensus, and affective expression (Table 2). Thus, high levels of dyadic adjustment reflect better adjustment and better quality of couple relationship [11,16,17,18,19,20,21].

Table 2.

Dimensions of couple dyadic adjustment.

The novelty of this study is the family approach when considering couples, including the private ambiance of the family, and considering the family health as a multiscale concept. We aim to address the knowledge gap about the relationship of couple dyadic adjustment and family health. The objective of this study is to describe and summarize research that analyzes the relationship between couple adjustment and family health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

A systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [22].

2.2. Search Methods

The following databases were consulted: Pubmed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Lilacs, Psicodoc, Cinahl, and Jstor. The search was carried out in January 2020 using the following search strategy: (conjugal or dyadic) and (“family functioning” or “dysfunctional family” or “family conflict” or “family health”).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) empirical study using quantitative methodology, to obtain articles that analyze the relationship between couple dyadic adjustment and family health; (b) written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese; (c) published between 2012 and 2019 (both included), because recent scientific production leaves obsolete other previously published [23]; (d) nuclear families.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) duplicated references; (b) non-access to full text article; (c) not relevant to the aim of the study, such as experiences of domestic violence or gender-based violence because of the multicausality of this issue itself; (d) studies with qualitative methodology; and (e) studies with low methodological quality after assessing the risk of bias.

Family health includes a wide range of complex concepts, such as functioning, adaptation, resilience, coping, etc. For this reason, its definition and the nature of the concept of family health is misleading and needs to be defined clearly and precisely. To make it operational, measurable, and facilitate its evaluation, it is necessary to design and use validated instruments [6]. Following the suggestion of these authors, we established as eligibility criteria quantitative studies that used measuring instruments for family health or any of its dimensions.

2.3. Search Outcome

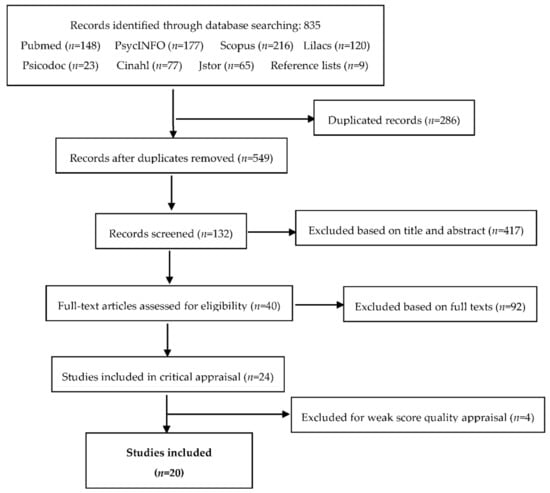

The initial electronic search yielded 835 references, from which 286 were duplicates. After reading the title and abstract, 417 references were excluded, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Then, 132 full text articles were screened, and 92 were excluded because the full text article did not report any relationship between couple dyadic adjustment and family health. Finally, a set of 24 full text articles were potentially relevant for eligibility.

2.4. Quality Assessment

Critical appraisal of 24 articles was conducted according to the Quality Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews of Observational Studies Score. It assesses methodological rigor according to five items that cover for the following aspects: external validity (1 item), reporting (2 items), bias (1 item), and confounding factors (1 item). Assessed studies can be scored as poor quality; satisfactory quality; or good quality [24]. Out of the 24 articles, 4 articles scored poor, 8 scored satisfactory, and 12 scored good regarding methodological quality. Articles that scored poor in the critical appraisal were excluded. Finally, 20 articles were selected for this systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the selection process.

2.5. Data Extraction

A critical reading of the selected articles was conducted. Two researchers extracted key descriptive details from the studies. Data were classified regarding authors, year of publication, country, aim, theoretical background, methodology (type of study, participants, data collection, and data analysis) and main findings. Ad hoc forms were created where researchers independently and by pairs included statistical results of each study. These forms were compared in order to resolve discrepancies between reviewers. When discrepancies were found, they were subject to review within the research group until consensus was reached.

2.6. Synthesis

It was agreed to adopt a data-driven thematic analysis. Results confirming a relationship between couple dyadic adjustment and family health were presented according to five categories identified by Lima-Rodríguez et al. [6,7]: climate, integrity, functioning, resilience, and coping. The review process, data extraction, and analysis were carried out by two independent researchers.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

The characteristics and main results of the reviewed studies are summarized in Table 3 [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Most of the studies followed a family approach within a theoretical framework; the Family System Theory was the most used. Two of the studies combined several theories to describe family approach [29,34], and three of them did not state the theoretical model used [25,31,41]. The majority of studies were conducted in the United States. Most of the studies were cross-sectional and prospective versus longitudinal or cohort study. The 20 studies addressed the couple subsystem from the perspective of dyadic adjustment (n = 10), the satisfaction (n = 5), or the conflict (n = 5). There was no uniformity in the term employed. Only six of the studies used the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) (Table 1).

Table 3.

Characteristics and main results from the reviewed studies.

3.2. Relationship between Couple Dyadic Adjustment and Family Climate

Results showed that the quality and satisfaction of the couple were important factors that can act as a trigger for the emotional climate of the family and affected the home learning environment [29]. The couple satisfaction was associated with positive family emotional expressiveness [29]. The quality of the couple relationship showed an indirect effect on parent–child relationship quality mediated by coparenting perceptions [44]. In this sense, greater couple dyadic adjustment was related to less family conflict, so when there was low couple dyadic adjustment, it was related to family aggression (verbal and physical acts of aggression) [40]. More so, partners’ conflict was related to higher levels of children’s temperamental emotionality [28,40], i.e., children as being more overtly and more relationally aggressive [28]. Dyadic adjustment predicted family conflict in children at age 3 years [28] and 5 years [40]. Dyadic adjustment also predicted lower aggressive behavior among adolescents [42].

3.3. Relationship between Couple Dyadic Adjustment and Family Integrity

Family integrity is considered to be the support and engagement behavior established among family members. Results demonstrated that couple adjustment was positively related to parenting alliance [26] or coparenting [26,37,41]. In this sense, parenting alliance was positively related to all dimensions of dyadic adjustment [26]. Partners’ satisfaction and couple relationship maintenance were positively related to supportive coparenting and negatively related to undermining coparenting in the couples with children aged from 9 to 13 years [36,37]. Couples with conflicting relationships based on negativity showed less support and more hostility in coparenting [41].

3.4. Relationship between Couple Dyadic Adjustment and Family Functioning

The couple dyadic adjustment was related to family functioning. On one hand, dyadic security, dyadic conflict, and couple relationship quality were related to interaction and family structure [32]. On the other hand, high conjugal adjustment was related to family flexibility and family satisfaction, and low couple dyadic adjustment was related to family disengagement and chaos [25]. It is necessary that family members contribute to proper functioning of the family unit. In this sense, the results revealed the relationship between couple dyadic adjustment and parental role performance [26,28,36] and in child functioning [25,30,31,34,35,38,41]. So, when couples engaged in activities to maintain their relationship and in actions to improve couple satisfaction, the effectiveness of their parental practices was greater than in those who did not invest in their relationship [36]. The couple conflict appeared positively related to parenting stress [26] and to more punitive and hostile parenting behaviors [28]. Similarly, lower couple dyadic adjustment was related to higher levels of children’s temperamental behavior [30], with problems in internalizing symptoms [43], internalizing and externalizing sadness, anger, and emotional reactions [31,34], hyperactivity and difficulties [25], difficult behavior with fathers [38], child negativity behavior [41], and suffering from psychopathological symptomatology i.e., anxiety, depression, withdrawal, somatic, attention, aggression, and delinquency in adolescents and young adults [31,35].

3.5. Relationship between Couple Dyadic Adjustment and Family Coping

When facing stressful life events, a family must rely on its ability and resources to address them. The reviewed articles studied couple dyadic adjustment during the prenatal phase [30], the birth of the first child [33,39], and transition to parenthood [27]. The results described that when couples exhibited a higher quality of couple interaction prior to the birth of their infant, they also showed more supportive coparenting behavior postpartum [39]. When couples exhibited higher conjugal satisfaction, they also showed more positive parenting experience, more parenting sense of competence and more positive parenting life change [33]. On the other hand, during the prenatal phase, couples that exhibited tension due to prolonged silences, stiff postures, and lack of eye contact, whining, or personal attacks, they showed higher coparenting conflict, pervasive disagreements, and higher use of hostility, sarcasm, and insulting behavior among family members [30]. In the prenatal stage, couples with a negative affective relationship were related to the emotional withdrawal in children at the age of 8 months and coparenting conflict at children aged 24 months [30]. In the transition to paternity, couple conflict predicted lower satisfaction, competitive and cooperative coparenting, and higher involvement in parenting [27].

4. Discussion

This systematic review identified the relationship between couple dyadic adjustment and family health within the domains of climate, integrity, functioning, and family coping. No results were identified related to family resilience. Results showed that greater couple dyadic adjustment was related to the higher emotional climate of the family, i.e., less family conflict and family aggression, higher levels of home learning environment, and positive family emotional expressiveness. These results are consistent with previous studies. Ackerman et al. [8] found that 37.3% of the variables explained by family climate are due to dyad adjustment. Schermerhorn et al. [9] identified a positive relationship between Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) and Family Environment Scale. Other authors attribute couple quality to the family emotional environment [45]. A recent review of the literature regarding couple relationships and children’s adjustment revealed that children growing up in a conflicting environment are at risk for problematic development [46].

Regarding family integrity, results showed that couple satisfaction and couple relationship maintenance were related to parenting alliance and supportive coparenting. Coparenting has been defined as a shared involvement from parents in children’s education, rearing, and life decisions [47]. Couple satisfaction affects coparenting quality in terms of involvement and cooperative coparenting, and therefore, children’s development [48]. Results are in line with the reflections of Boehs et al. [49] on the routines and rituals of the family, which is part of family integrity. They stated that they are constantly modified to meet basic needs of family members such as a spouse´s needs or the upbringing of children. Other authors related dyad disadjustments to couple dissolution or similarly, the end of family integrity through divorce or separation [50].

Higher couple dyadic adjustment was related to family efficacy, family flexibility, family satisfaction, and good performance of family member’s roles for proper functioning of the family unit. Low couple dyadic adjustment was related to family disengagement, chaos, parenting stress, and more punitive and hostile parenting behaviors. The authors have previously described a relationship between couple adjustment and family functioning [51]. Eichelsheim et al. [52] assumed that couple dyad members had to make adjustments not to alter relationships with other members of the family and the family functioning.

The reviewed studies did not address the relationship between couple dyadic adjustment and family resilience. Gómez and Kotliarenco [53] identified those environments that activate family resilience to recuperate optimum functioning level and common welfare: situations of chronic risk, significant crisis, or family tension.

Finally, the couple dyadic adjustment was related to family coping when there were problems or stressful life events. In this case, the reviewed articles studied couple dyadic adjustment during the prenatal phase, the birth of the first child, and the transition to parenthood. When couples exhibited higher satisfaction with their relationship, they also showed more positive parenting experience, more parenting sense of competence, and more positive parenting life change. Previous studies related higher couple quality with less conflicts and with more positive results in resolving family coping [54]. In this sense, recognizing difficult situations for couples to deal with would be the first step in coping and looking for advice provided by via education programs or through personal, family, or couples therapy [55].

For more than three decades, researchers such as Driver et al. [56] have studied the interactional patterns of couples’ success or failure. The success of a partners’ relationship depends primarily on how the couple handles conflicts. The way a conflict is used and resolved in the couple dyad relationship suggests the health and longevity of the family unit because healthy couples try to repair their relationship [57]. For many researchers, dyadic adjustment appears to be an important aspect of well-being [58]. To many researchers, the couple relationship is the basis of the family, its relational center [59,60], and the key organizational factor of family life [50]. Olson and Gorall [61] merged the concepts of couple and family dynamics in the Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems. They considered that balanced families will function more adequately across the family life cycle and tend to be healthier families. They considered the couple subsystem as the leader within the family with the ability to demonstrate flexibility in roles, relationships, and rules, including control, discipline, and role sharing to adapt to stressors, thus promoting family health. Other researchers also identified the partners’ relationship as the principal variable and fundamental for the maintenance of family health [8,9].

Family health research is of great interest to many health professionals because family plays an essential role in the health and illnesses of people [62], and because the family should be considered as a system in which the interactions between family members have to be the target for the health interventions. However, there is a lack of care and attention from health professionals when dealing with family units [63]. They highlight the lack of a theoretical model or a strategic diagnosis and evaluation plan nor care or efficient treatment in the environment of family health. Researchers agree to define family health as a changing and dynamic status that allows growth and satisfaction to family members’ ‘needs and family itself’. It also allows the interaction between individual, family and society, problem solving, skills to manage changes and/or stressful events as well as to adapt to crisis situations [5]. In spite of all these, few clinical research studies employ the family health variable as a study target as well as a multiscale concept. The Lima-Rodriguez model [6,7] based on five interconnected dimensions could be a valid proposal for future studies investigating family health.

Health professionals would derive value from being qualified and trained to interact with the family and aim to optimize its health. Their responsibilities could include a thorough assessment of the family as a unit [64], identifying family problems as well as the availability of resources, and delivering customized education for families to identify their strengths and overcome new threatening situations or continue meeting their health needs [15].

Limitations

The present review may contain biases. Inclusion criteria such as language, the period of time, or quantitative design may have conditioned the identification and recovery of relevant articles. However, in order to minimize bias, the references of the selected studies were checked to include other results to our review, and we addressed the results and their categorization through consensus and individual and group analysis. Another limitation that should be acknowledged is that this review focuses on couple dyadic adjustment as opposed to other forms of caregiving relationships. There are a wide variety of families and situations that are not reflected in this systematic review that perhaps could give a wider approach and enriches the results from this review. Likewise, we did not take into consideration the families with children with special needs/disabilities, as results only refer to typically developed children. By establishing quantitative methodology studies as the conclusion criterion for this review, the results obtained from a qualitative approach were excluded. Due to the diversity of current families and the strong cultural component of the concept of family health, a qualitative approach is essential for a complete understanding of the phenomenon. So, qualitative research in this area would also be useful in combination with quantitative work.

5. Conclusions

Findings from this review revealed a consensus about the relationship between couple dyadic adjustment and family health. Although the leading role of the couple within the family has been extensively studied, this review fills the gap of knowledge about the relationship between dyadic adjustment and family health. The originality of this study also lies in the multidimensional approach to the concept of family health compared to previous reviews.

These results could help to develop strategies to improve the quality of the couple relationship and to contribute to a good family climate. As couple dyadic adjustment can aggravate family integrity, health professionals should care for family susceptibility and vulnerability in this sense. In addition, they could focus their interventions on the couple subsystem to improve the specific areas of family functioning: affective involvement, roles, communication, and problem solving. On one hand, the couple subsystem has knowledge, experiences, and competences that can contribute to family resilience. On the other hand, when the couple enters into conflicts, the family may lose some of these resources and become fragile in order to face of the impact of stressors. Finally, the challenges of the couple relationship could trigger processes of family coping. Caring for the couple subsystem could promote family health and foster the development of its members.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.J.-P. and M.R.-M.; methodology, N.J.-P.; software, J.C.P.-L.; validation, N.J.-P., M.R.-M. and J.G.-S.; formal analysis, J.C.P.-L.; investigation, L.R.-B.; resources, N.J.-P.; data curation, J.C.P.-L. and L.R.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.-M.; writing—review and editing, J.G.-S.; visualization, M.R.-M.; supervision, N.J.-P.; project administration, L.R.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bailón Muñoz, E.; de la Revilla Ahumada, L. La atención familiar, la asignatura pendiente. Aten. Primaria 2011, 43, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid-Monckton, P.; Pedrão, L.J. Protective and Family Risk Factors Related to Adolescent Drug Use. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2011, 19, 737–745. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva Gómez, E.; Villa Guardiola, V.J. Hacia un concepto interdisciplinario de la familia en la globalización. Justicia Juris 2014, 10, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demby, K.P.; Riggs, S.A.; Kaminski, P.L. Attachment and Family Processes in Children’s Psychological Adjustment in Middle Childhood. Fam. Process. 2017, 56, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, C.; Benzein, E. Family Health Conversations: How Do They Support Health? Nurs. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Rodriguez, J.S.; Lima Serrano, M.; Jimenez Picon, N.; Dominguez Sanchez, I. Consistencia interna y validez de un cuestionario para medir la autopercepcion del estado de salud familiar. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2012, 86, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima-Rodríguez, J.S.; Lima-Serrano, M.; Jiménez-Picón, N.; Domínguez-Sánchez, I. Content validation of the Self-perception of Family Health Status scale using the Delphi technique. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2013, 21, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman, R.A.; Kashy, D.A.; Donnellan, M.B.; Conger, R.D. Positive-engagement behaviors in observed family interactions: A social relations perspective. J. Fam. Psychol. 2011, 25, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schermerhorn, A.C.; D’Onofrio, B.M.; Turkheimer, E.; Ganiban, J.M.; Spotts, E.L.; Lichtenstein, P.; Reiss, D.; Neiderhiser, J.M. A genetically informed study of associations between family functioning and child psychosocial adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 47, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicavo, N.; Vera, C. Incidencia del ajuste diádico y sentido del humor en la satisfacción marital. Rev. Psicolog. 2011, 13, 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, T.F.; Slatcher, R.B.; Trombello, J.M.; McGinn, M.M. Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 140–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erel, O.; Burman, B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Marital Conflict and Children. An. Emotional Security Perspective; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar, A.; Buehler, C. Interparental Conflict and Parenting Behaviors: A Meta-Analytic Review. Fam. Relat. 2000, 49, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, F.W.; Ngu, S.F. Predictors of family and marital functioning at early postpartum. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 2588–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerach, G.; Magal, O. Exposure to stress during childbirth, dyadic adjustment, partner’s resilience, and psychological distress among first-time fathers. Psychol. Men. Masc. 2017, 18, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.; Fonseca, A.; Canavarro, M.C.; Pereira, M. Dyadic coping and dyadic adjustment in couples with women with high depressive symptoms during pregnancy. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2018, 36, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroufizadeh, S.; Omani-Samani, R.; Hosseini, M.; Almasi-Hashiani, A.; Sepidarkish, M.; Amini, P. The Persian version of the revised dyadic adjustment scale (RDAS): A validation study in infertile patients. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampis, J.; Cataudella, S.; Agus, M.; Busonera, A.; Skowron, E.A. Differentiation of Self and Dyadic Adjustment in Couple Relationships: A Dyadic Analysis Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Fam. Process. 2019, 58, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, T.; Brites, R.; Hipólito, J.; Pires, M.; Nunes, O. Dyadic coping, marital adjustment and quality of life in couples during pregnancy: An actor-partner approach. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2020, 38, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Canavarro, M.C.; Pereira, M. The relationship between dyadic coping and dyadic adjustment among HIV-serodiscordant couples. AIDS Care 2021, 33, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlock, D.; Anderson, J. Teaching and Assessing the Database Searching Skills of Student Nurses. Nurse Educ. 2007, 32, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.C.; Cheung, C.S.; Hart, G.J. Development of a quality assessment tool for systematic reviews of observational studies (QATSO) of HIV prevalence in men having sex with men and associated risk behaviours. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2008, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, R.; Santamaria, F.; Ioverno, S.; Fontanesi, L.; Baumgartner, E.; Laghi, F.; Lingiardi, V. Lesbian Mother Families and Gay Father Families in Italy: Family Functioning, Dyadic Satisfaction, and Child Well-Being. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2015, 12, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisasca, E.; Miragoli, S.; Di Blasio, P. Is the Relationship Between Marital Adjustment and Parenting Stress Mediated or Moderated by Parenting Alliance? Eur. J. Psychol. 2014, 10, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, C.; Umemura, T.; Mann, T.; Jacobvitz, D.; Hazen, N. Marital Quality over the Transition to Parenthood as a Predictor of Coparenting. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 3636–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, H.-S.; Shin, N.; Kim, M.-J.; Hong, J.S.; Choi, M.-K.; Kim, S. Influence of marital conflict on young children’s aggressive behavior in South Korea: The mediating role of child maltreatment. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1742–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froyen, L.C.; Skibbe, L.E.; Bowles, R.P.; Blow, A.J.; Gerde, H.K. Marital Satisfaction, Family Emotional Expressiveness, Home Learning Environments, and Children’s Emergent Literacy. J. Marriage Fam. 2013, 75, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, M.I.; Murphy, S.E.; Benner, A.D.; Jacobvitz, D.B.; Hazen, N.L. Marital, parental, and whole-family predictors of toddlers’ emotion regulation: The role of parental emotional withdrawal. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayatbakhsh, R.; Clavarino, A.M.; Williams, G.M.; Bor, W.; O’Callaghan, M.J.; Najman, J.M. Family structure, marital discord and offspring’s psychopathology in early adulthood: A prospective study. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 22, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, J.; Yuen, C.X.; Bornstein, M.H.; Putnick, D.L.; Hendricks, C. The relations of family members’ unique and shared perspectives of family dysfunction to dyad adjustment. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kershaw, T.; Murphy, A.; Lewis, J.; Divney, A.; Albritton, T.; Magriples, U.; Gordon, D. Family and Relationship Influences on Parenting Behaviors of Young Parents. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, K.M.; Bregman, H.R.; Malik, N.M. Family boundary structures and child adjustment: The indirect role of emotional reactivity. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 2839–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, O.; Mota, C.P. Interparental Conflicts and the Development of Psychopathology in Adolescents and Young Adults. Paidéia 2014, 24, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Merrifield, K.A.; Gamble, W.C. Associations Among Marital Qualities, Supportive and Undermining Coparenting, and Parenting Self-Efficacy. J. Fam. Issues 2013, 34, 510–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, M.F.; Ribeiro, T.; Shelton, K.H. Marital satisfaction and partners’ parenting practices: The mediating role of coparenting behavior. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeto, A.; Mangelsdorf, S.C.; Brown, G.L. Roles of family cohesiveness, marital adjustment, and child temperament in predicting child behavior with mothers and fathers. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2014, 31, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Mangelsdorf, S.C. Parent Characteristics and Early Coparenting Behavior at the Transition to Parenthood. Soc. Dev. 2013, 22, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo-Yoo, Y.; Adamsons, K.L.; Robinson, J.L.; Sabatelli, R.M. Longitudinal Influence of Paternal Distress on Children’s Representations of Fathers, Family Cohesion, and Family Conflict. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 591–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, L.; Bradbury, T.N. Marital interaction prior to parenthood predicts parent–child interaction 9 years later. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smokowski, P.R.; Rose, R.A.; Bacallao, M.; Cotter, K.L.; Evans, C.B.R. Family dinamics and and aggressive behavior in latino adolescents. Cultur. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2017, 23, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, C.P.; Costa, C.B.; Einsfeld, P.; Silva, A.G.M.; Koch, C. Marital relations, parenting, and coparenting: Associations with externalizing and internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents. Estud. Psicol. 2017, 34, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Holland, A.S.; McElwain, N.J. Maternal and patemal perceptions of coparenting as a link between marital quality and the parent-toddler relationship. J. Fam. Psychol. 2013, 27, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldinger, R.J.; Schulz, M.S.; Hauser, S.T.; Allen, J.P.; Crowell, J.A. Reading Others’ Emotions: The Role of Intuitive Judgments in Predicting Marital Satisfaction, Quality, and Stability. J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaez, E.; Indran, R.; Abdollahi, A.; Juhari, R.; Mansor, M. How marital relations affect child behavior: Review of recent research. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2015, 10, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parent. Sci. Pract. 2003, 3, 95–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, C.; Wagner, A.; Sarriera, J. A qualidade conjugal como preditora dos estilos educativos parentais: O perfi l discriminante de casais com fi lhos adolescentes. Psicología 2008, 22, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehs, A.E.; Manfrini, G.C.; Rumor, P.C.F.; Jorge, C.S.G. Rituais e rotinas familiares: Reflexão teórica para a enfermagem no cuidado à família. Ciência Cuid. e Saúde 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pampliega, A.; Sanz, M.; Iraurgi, I.; Iriarte, L. Impacto de la ruptura matrimonial en el bienestar físico y psicológico de los hijos. Síntesis de resultados de una línea de investigación. La Revue Du REDIF 2009, 2, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, I.W.; McDermut, W.; Gordon, K.C.; Keitner, G.I.; Ryan, C.E.; Norman, W. Personality and family functioning in families of depressed patients. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2000, 109, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichelsheim, V.I.; Deković, M.; Buist, K.L.; Cook, W.L. The Social Relations Model in Family Studies: A Systematic Review. J. Marriage Fam. 2009, 71, 1052–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, E.; Kotliarenco, M.A. Family Resilience: A research and intervention approach with multiproblem families. Rev. Psicol. 2010, 19, 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, E.M.; Wilson, J.; Shamir, H. Reactions of Chilean and US children to marital discord. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2003, 27, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.; Warfel, R.; Johnson, J.; Smith, R.; McKinney, P. Which relationship skills count most? J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2013, 12, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, J.; Tabares, A.; Shapiro, A.F.; Gottman, J.M. Couple Interaction in Happy and Unhappy Marriages. In Normal Family Processes: Growing Diversity and Complexity; The Guilfo: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, J.; Padgett, D.; Steele, R.; Tabacco, A.; Harmon, S.M. Family Health Care Nursing. In Theory, Practice and Research, 5th ed.; F. A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve, L.; Trudel, G.; Préville, M.; Dargis, L.; Boyer, R.; Bégin, J. Dyadic Adjustment Scale: A Validation Study among Older French-Canadians Living in Relationships. Can. J. Aging La Rev. Can. du Vieil. 2015, 34, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés-Funes, F.; Bueno, J.P.; Narváez, A.; García-Valverde, A.; Guerrero-Gutiérrez, L. Funcionamiento familiar y adaptación psicológica en oncología. Psicooncología 2013, 9, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.T.; Sturge-Apple, M.L.; Woitach, M.J.; Cummings, E.M. A process analysis of the transmission of distress from interparental conflict to parenting: Adult relationship security as an explanatory mechanism. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 45, 1761–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, D.H.; Gorall, D.N. Circumplex model of marital and family systems. In Normal Family Processes: Growing Diversity and Complexity; Guilford P: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 514–548. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.C.L.D.S.R.; Silva, L.; Bousso, R.S. Approaching the family in the Family Health Strategy: An integrative literature review. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2011, 45, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Östlund, U.; Bäckström, B.; Lindh, V.; Sundin, K.; Saveman, B.-I. Nurses’ fidelity to theory-based core components when implementing Family Health Conversations-a qualitative inquiry. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2015, 29, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Rodríguez, J.S.; Lima-Serrano, M.; Sáez-Bueno, Á. Intervenciones enfermeras orientadas a la familia. Enf. Clin. 2009, 19, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).