Impact of School-Based Physical Activity Intervention on Obesity and Physical Parameters in Children: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

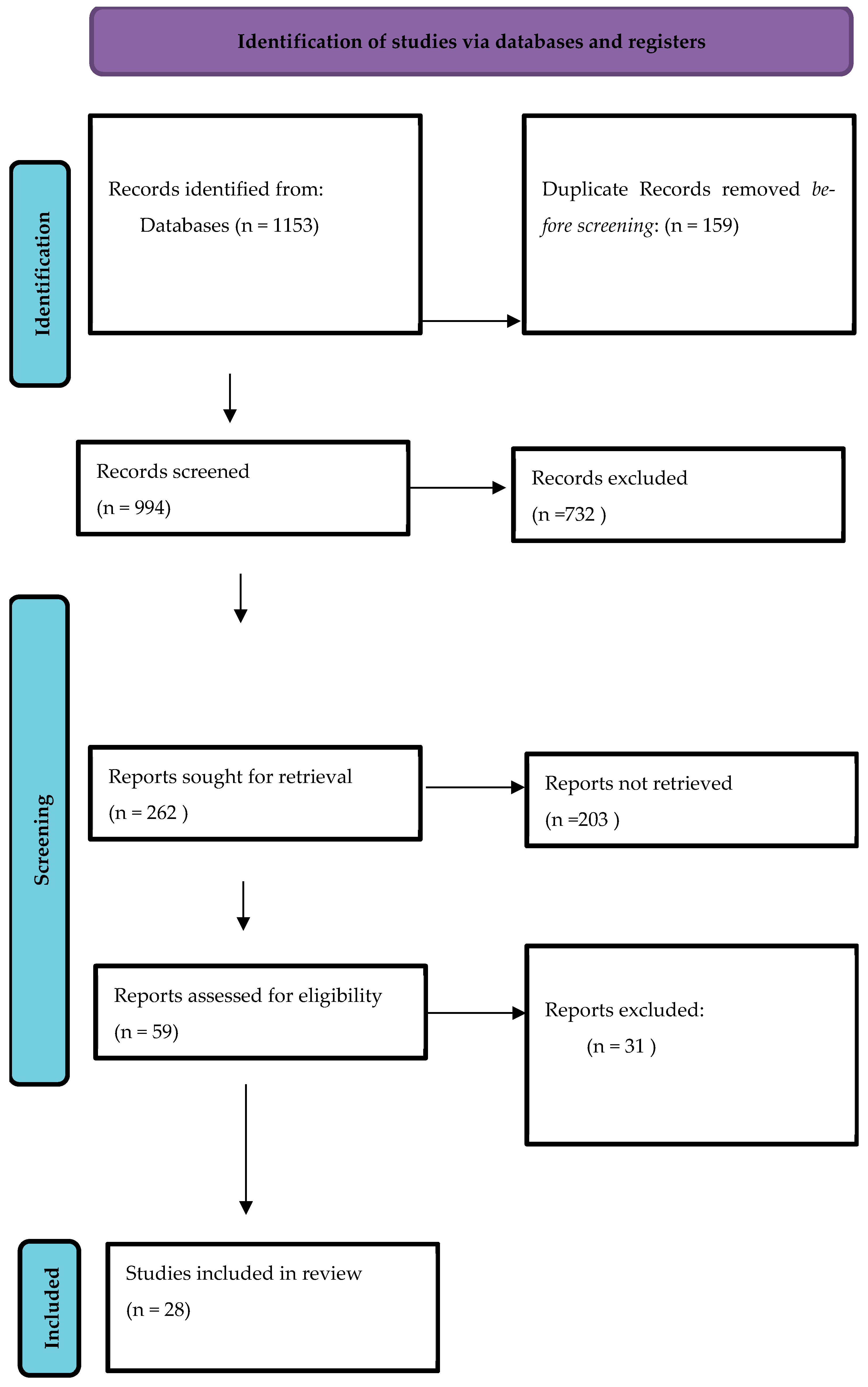

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Included dietary, behavioral, or multi-component lifestyle interventions in combination with physical activity.

- Were non-randomized, observational, cross-sectional, qualitative, or pilot studies without a control group.

- Involved children with chronic disease-specific interventions (e.g., asthma-specific activity programs).

- Were conducted outside formal school settings (e.g., community, after-school clubs, sports academies).

- Did not report any obesity-related or physical activity-related outcomes.

- Were not published in English.

- Included participants younger than 5 or older than 18 years.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Obesity

3.2. Physical Activity

Physical Fitness and Cardiorespiratory Fitness

4. Risk of Bias

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| cpm | Counts Per Minute |

| HIIT | High-Intensity Interval Training |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity |

| PACER | Progressive Aerobic Cardiovascular Endurance Run |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| VO2 max | Maximal Oxygen Uptake |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Reilly, J.J.; Aubert, S.; Brazo-Sayavera, J.; Liu, Y.; Cagas, J.Y.; Tremblay, M.S. Surveillance to improve physical activity of children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 2022, 100, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvo, D.; Garcia, L.; Reis, R.S.; Stankov, I.; Goel, R.; Schipperijn, J.; Hallal, P.C.; Ding, D.; Pratt, M. Physical activity promotion and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Building synergies to maximize impact. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.M.; Katre, P.A.; Kumaran, K.; Joglekar, C.; Osmond, C.; Bhat, D.S.; Lubree, H.; Pandit, A.; Yajnik, C.S.; Fall, C.H. Tracking of cardiovascular risk factors from childhood to young adulthood—The Pune Children’s Study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 175, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsbo, J.; Krustrup, P.; Duda, J.; Hillman, C.; Andersen, L.B.; Weiss, M.; Williams, C.A.; Lintunen, T.; Green, K.; Hansen, P.R.; et al. The Copenhagen Consensus Conference 2016: Children, youth, and physical activity in schools and during leisure time. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1177–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokye, N.K.; Trueman, P.; Green, C.; Pavey, T.G.; Taylor, R.S. Physical activity and health related quality of life. BMC Public. Health 2012, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, Y.S.; Stormark, K.M.; Nordhus, I.H.; Mæhle, M.; Sand, L.; Ekornås, B.; Pallesen, S. Factors associated with low self-esteem in children with overweight. Obes. Facts 2012, 5, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chaddha, A.; Jackson, E.A.; Richardson, C.R.; Franklin, B.A. Technology to Help Promote Physical Activity. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 119, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuth, A.G.; Hallal, P.C. Temporal Trends in Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. J. Phys. Act. Health 2009, 6, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuksel, H.S.; Şahin, F.N.; Maksimovic, N.; Drid, P.; Bianco, A. School-Based Intervention Programs for Preventing Obesity and Promoting Physical Activity and Fitness: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, L.L.; King, L.; Espinel, P.; Okely, A.D.; Bauman, A. Methods of the NSW Schools Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey 2010 (SPANS 2010). J. Sci. Med. Sport 2011, 14, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slusser, W. Family physicians and the childhood obesity epidemic. Am. Fam. Physician 2008, 78, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lifshitz, F. Obesity in children. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2008, 1, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lim, H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int. Rev. Psychiatry Abingdon Engl. 2012, 24, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, G.C.; Viner, R. Pubertal transitions in health. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2007, 369, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.M.; Hardy-Johnson, P.L.; Inskip, H.M.; Morris, T.; Parsons, C.M.; Barrett, M.; Hanson, M.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Baird, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions with health education to reduce body mass index in adolescents aged 10 to 19 years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pavón, D.; Kelly, J.; Reilly, J.J. Associations between objectively measured habitual physical activity and adiposity in children and adolescents: Systematic review. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2010, 5, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piirtola, M.; Kaprio, J.; Waller, K.; Heikkilä, K.; Koskenvuo, M.; Svedberg, P.; Silventoinen, K.; Kujala, U.M.; Ropponen, A. Leisure-time physical inactivity and association with body mass index: A Finnish Twin Study with a 35-year follow-up. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriemler, S.; Meyer, U.; Martin, E.; Van Sluijs, E.M.F.; Andersen, L.B.; Martin, B.W. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: A review of reviews and systematic update. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, Y.; Höner, O. Physical activity interventions in the school setting: A systematic review. Psychol. Sport. Exerc. 2012, 13, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Kop, J.H.; Van Kernebeek, W.G.; Otten, R.H.J.; Toussaint, H.M.; Verhoeff, A.P. School-Based Physical Activity Interventions in Prevocational Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.S.; Tidwell, D.K.; Hall, M.E.; Lee, M.L.; Briley, C.A.; Hunt, B.P. A meta-analysis of school-based obesity prevention programs demonstrates limited efficacy of decreasing childhood obesity. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynynen, S.T.; van Stralen, M.M.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Araújo-Soares, V.; Hardeman, W.; Chinapaw, M.J.; Vasankari, T.; Hankonen, N. A systematic review of school-based interventions targeting physical activity and sedentary behaviour among older adolescents. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 9, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R. Physical education and sport in schools: A review of benefits and outcomes. J. Sch. Health 2006, 76, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R.; Armour, K.; Kirk, D.; Jess, M.; Pickup, I.; Sandford, R. The educational benefits claimed for physical education and schoosport: An academic review. Res. Pap. Educ. 2009, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, K.E.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Callister, R.; Lubans, D.R. Physical Activity and Skills Intervention: SCORES Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jago, R.; Tibbitts, B.; Sanderson, E.; Bird, E.L.; Porter, A.; Metcalfe, C.; Powell, J.E.; Gillett, D.; Sebire, S.J. Action 3:30R: Results of a cluster randomised feasibility study of a revised teaching assistant-led extracurricular physical activity intervention for 8 to 10 year olds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Greeff, J.W.; Hartman, E.; Mullender-Wijnsma, M.J.; Bosker, R.J.; Doolaard, S.; Visscher, C. Long-term effects of physically active academic lessons on physical fitness and executive functions in primary school children. Health Educ. Res. 2016, 31, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, J.L.; Sutherland, R.; Campbell, L.; Morgan, P.J.; Lubans, D.R.; Nathan, N.; Wolfenden, L.; Okely, A.D.; Davies, L.; Williams, A.; et al. Effects of a school-based physical activity intervention on adiposity in adolescents from economically disadvantaged communities: Secondary outcomes of the Physical Activity 4 Everyone RCT. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarani, J.; Grøntved, A.; Muca, F.; Spahi, A.; Qefalia, D.; Ushtelenca, K.; Kasa, A.; Caporossi, D.; Gallotta, M.C. Effects of two physical education programmes on health- and skill-related physical fitness of Albanian children. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.R.; Smith, J.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Dally, K.A.; Okely, A.D.; Salmon, J.; Morgan, P.J. Assessing the sustained impact of a school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent boys: The ATLAS cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.L.; Nathan, N.K.; Lubans, D.R.; Cohen, K.; Davies, L.J.; Desmet, C.; Cohen, J.; McCarthy, N.J.; Butler, P.; Wiggers, J.; et al. An RCT to facilitate implementation of school practices known to increase physical activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarp, J.; Domazet, S.L.; Froberg, K.; Hillman, C.H.; Andersen, L.B.; Bugge, A. Effectiveness of a School-Based Physical Activity Intervention on Cognitive Performance in Danish Adolescents: LCoMotion—Learning, Cognition and Motion—A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Franken IHA, editor. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Greene, J.L.; Hansen, D.M.; Gibson, C.A.; Sullivan, D.K.; Poggio, J.; Mayo, M.S.; Lambourne, K.; Szabo-Reed, A.N.; et al. Physical activity and academic achievement across the curriculum: Results from a 3-year cluster-randomized trial. Prev. Med. 2017, 99, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsdale, C.; Lester, A.; Owen, K.B.; White, R.L.; Peralta, L.; Kirwan, M.; Diallo, T.M.O.; Maeder, A.J.; Bennie, A.; MacMillan, F.; et al. An internet-supported school physical activity intervention in low socioeconomic status communities: Results from the Activity and Motivation in Physical Education (AMPED) cluster randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Have, M.; Nielsen, J.H.; Ernst, M.T.; Gejl, A.K.; Fredens, K.; Grøntved, A.; Kristensen, P.L. Classroom-based physical activity improves children’s math achievement—A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hoor, G.A.; Rutten, G.M.; van Breukelen, G.J.P.; Kok, G.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Meijer, K.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Feron, F.J.M.; Crutzen, R.; Schols, A.M.J.W.; et al. Strength exercises during physical education classes in secondary schools improve body composition: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, A.A.; Eather, N.; Smith, J.J.; Hillman, C.H.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Nilsson, M.; Costigan, S.A.; Noetel, M.; Lubans, D.R. Feasibility and Preliminary Efficacy of a Teacher-Facilitated High-Intensity Interval Training Intervention for Older Adolescents. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 31, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, I.; Schindler, C.; Adams, L.; Endes, K.; Gall, S.; Gerber, M.; Htun, N.S.N.; Nqweniso, S.; Joubert, N.; Probst-Hensch, N.; et al. Effect of a multidimensional physical activity intervention on body mass index, skinfolds and fitness in South African children: Results from a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, K.A.; Robbins, L.B.; Ling, J.; Sharma, D.B.; Dalimonte-Merckling, D.M.; Voskuil, V.R.; Kaciroti, N.; Resnicow, K. Effects of the Girls on the Move randomized trial on adiposity and aerobic performance (secondary outcomes) in low-income adolescent girls. Pediatr. Obes. 2019, 14, e12559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, L.B.; Ling, J.; Sharma, D.B.; Dalimonte-Merckling, D.M.; Voskuil, V.R.; Resnicow, K.; Kaciroti, N.; Pfeiffer, K.A. Intervention effects of “Girls on the Move” on increasing physical activity: A group randomized trial. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, T.; Allen, D.B.; Eickhoff, J.C.; Carrel, A.L. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Based Physical Activity Recommendations Do Not Improve Fitness in Real-World Settings. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seljebotn, P.H.; Skage, I.; Riskedal, A.; Olsen, M.; Kvalø, S.E.; Dyrstad, S.M. Physically active academic lessons and effect on physical activity and aerobic fitness. The Active School study: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 13, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, S.; Yin, J.; Fu, Q.; Ren, H.; Jin, T.; Zhu, J.; Howard, J.; Lan, T.; Yin, Z. Impact on physical fitness of the Chinese CHAMPS: A clustered randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breheny, K.; Passmore, S.; Adab, P.; Martin, J.; Hemming, K.; Lancashire, E.R.; Frew, E. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of The Daily Mile on childhood weight outcomes and wellbeing: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Obes. 2020, 44, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketelhut, S.; Kircher, E.; Ketelhut, S.R.; Wehlan, E.; Ketelhut, K. Effectiveness of Multi-activity, High-intensity Interval Training in School-aged Children. Int. J. Sports Med. 2020, 41, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maglie, A.; Marsigliante, S.; My, G.; Colazzo, S.; Muscella, A. Effects of a physical activity intervention on schoolchildren fitness. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Yucheng, T.; Shu, L.; Yu, Z. Effects of school-based high-intensity interval training on body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiometabolic markers in adolescent boys with obesity: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, R.L.; Campbell, E.M.; Lubans, D.R.; Morgan, P.J.; Nathan, N.K.; Wolfenden, L.; Okely, A.D.; Gillham, K.E.; Hollis, J.L.; Oldmeadow, C.J.; et al. The Physical Activity 4 Everyone cluster randomized trial: 2-year outcomes of a school physical activity intervention among adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jago, R.; Edwards, M.J.; Sebire, S.J.; Tomkinson, K.; Bird, E.L.; Banfield, K.; May, T.; Kesten, J.M.; Cooper, A.R.; Powell, J.E.; et al. Effect and cost of an after-school dance programme on the physical activity of 11–12 year old girls: The Bristol Girls Dance Project, a school-based cluster randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, A.; Murphy, M.H.; Nevill, A.; Gallagher, A.M. Effects of a peer-led Walking In ScHools intervention (the WISH study) on physical activity levels of adolescent girls: A cluster randomised pilot study. Trials 2018, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, S.; McCarren, A.; McGrane, B.; Powell, D.; Issartel, J. The Youth-Physical Activity Towards Health (Y-PATH) intervention: Results of a 24 month cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsigliante, S.; Gómez-López, M.; Muscella, A. Effects on Children’s Physical and Mental Well-Being of a Physical-Activity-Based School Intervention Program: A Randomized Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, S.; Buoncristiano, M.; Gelius, P.; Abu-Omar, K.; Pattison, M.; Hyska, J.; Duleva, V.; Musić Milanović, S.; Zamrazilová, H.; Hejgaard, T.; et al. Physical activity, screen time, and sleep duration of children aged 6–9 years in 25 countries: An analysis within the WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) 2015–2017. Obes. Facts 2021, 14, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, W.B.; Malina, R.M.; Blimkie, C.J.; Daniels, S.R.; Dishman, R.K.; Gutin, B.; Hergenroeder, A.C.; Must, A.; Nixon, P.A.; Pivarnik, J.M.; et al. Evidence-based physical activity for school-age youth. J. Pediatr. 2005, 146, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.C.; Kuramoto, L.K.; Schulzer, M.; Retallack, J.E. Effect of school-based physical activity interventions on body mass index in children: A meta-analysis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2009, 180, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, P.H.; Nobre, M.R.C.; Da Silveira, J.A.C.; De Aguiar Carrazedo Taddei, J.A. The effect of school-based physical activity interventions on body mass index: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clinics 2013, 68, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M. School-based interventions for childhood and adolescent obesity. Obes. Rev. 2006, 7, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Van Cauwenberghe, E.; Spittaels, H.; Oppert, J.M.; Rostami, C.; Brug, J.; Van Lenthe, F.; Lobstein, T.; Maes, L. School-based interventions promoting both physical activity and healthy eating in Europe: A systematic review within the HOPE project. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Summerbell, C. Systematic review of school-based interventions that focus on changing dietary intake and physical activity levels to prevent childhood obesity: An update to the obesity guidance produced by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 110–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nally, S.; Carlin, A.; Blackburn, N.E.; Baird, J.S.; Salmon, J.; Murphy, M.H.; Gallagher, A.M. The effectiveness of school-based interventions on obesity-related behaviours in primary school children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Children 2021, 8, 489, Erratum in Children 2024, 11, 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091092.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil-Sztramko, S.E.; Caldwell, H.; Dobbins, M. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021, 9, CD007651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Love, R.; Adams, J.; Van Sluijs, E.M.F. Are school-based physical activity interventions effective and equitable? A meta-analysis of cluster randomized controlled trials with accelerometer-assessed activity. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borde, R.; Smith, J.J.; Sutherland, R.; Nathan, N.; Lubans, D.R. Methodological considerations and impact of school-based interventions on objectively measured physical activity in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, T.W. The biological basis of physical activity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1998, 30, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, N.C.; Oestergaard, L.; Rasmussen, M.G.B.; Schmidt-Persson, J.; Larsen, K.T.; Juhl, C.B. How to get children moving? The effectiveness of school-based interventions promoting physical activity in children and adolescents—A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled- and controlled studies. Health Place 2024, 89, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olds, T.; Ferrar, K.E.; Gomersall, S.R.; Maher, C.; Walters, J.L. The Elasticity of Time: Associations Between Physical Activity and Use of Time in Adolescents. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beni, S.; Fletcher, T.; Ní Chróinín, D. Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education and Youth Sport: A Review of the Literature. Quest 2017, 69, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladwig, M.A.; Vazou, S.; Ekkekakis, P. “My Best Memory Is When I Was Done with It”: PE Memories Are Associated with Adult Sedentary Behavior. Transl. J. Am. Coll. Sports Med. 2018, 3, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manojlovic, M.; Roklicer, R.; Trivic, T.; Milic, R.; Maksimović, N.; Tabakov, R.; Sekulic, D.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P. Effects of school-based physical activity interventions on physical fitness and cardiometabolic health in children and adolescents with disabilities: A systematic review. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1180639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Sample Size (n) | Age (Years) | Duration | Intervention Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen (2015) | Cluster RCT | 460 | 8–9 | 12 months | PA, CRF, anthropometry |

| Jago (2015) | Cluster RCT | 571 | 11–12 | 20 weeks | Dance sessions |

| De Greeff (2016) | Cluster RCT | 499 | 8 | 24 months | Active academic lessons |

| Hollis (2016) | Cluster RCT | 985 | 11 | 24 months | School-based PA programme |

| Jarani (2016) | Cluster RCT | 760 | 7–10 | 5 months | Exercise- vs. game-based PE |

| Lubans (2016) | Cluster RCT | 361 | 12–14 | 20 weeks | ATLAS programme |

| Sutherland (2016) | Cluster RCT | 985 | 14 | 24 months | PA during school day |

| Tarp (2016) | Cluster RCT | 632 | 12–14 | 20 weeks | PA periods, recess, homework |

| Donnelly (2017) | Cluster RCT | 1902 | 8 | 3 years | Active academic lessons |

| Lonsdale (2017) | Cluster RCT | 1421 | 12–13 | 7–8 months | AMPED teacher-led PA |

| Sutherland (2017) | Cluster RCT | 111 | 5–7 | 6 months | Modified SCORES |

| Carlin (2018) | Cluster RCT | 197 | 11–13 | 12 weeks | Peer-led brisk walking |

| Have (2018) | Cluster RCT | 450 | 7 | 12 months | PA integrated into math lessons |

| Ten Hoor (2018) | Cluster RCT | 508 | 11–15 | 12 months | Strength training + motivation |

| Belton (2019) | Cluster RCT | 534 | 12–13 | 24 months | Y-PATH |

| Jago (2019) | Cluster RCT | 252 | 8–10 | 15 weeks | Action 3:30R |

| Leahy (2019) | Cluster RCT | 68 | 16 | 14 weeks | Teacher-led HIIT |

| Müller (2019) | Cluster RCT | 746 | 9–14 | 10 months | Multidimensional PA |

| Pfeiffer (2019) | Cluster RCT | 1519 | 12 | 17 weeks | Girls on the Move |

| Robbins (2019) | Cluster RCT | 1519 | 10–15 | 17 weeks | Girls on the Move (PA focus) |

| Seibert (2019) | Cluster RCT | 4894 | 11 | 9 months | CDC PA strategies |

| Seljebotn (2019) | Cluster RCT | 447 | 9–10 | 10 months | Active lessons + recess + homework |

| Zhou (2019) | Cluster RCT | 680 | 12–13 | 8 months | CHAMPS intervention |

| Breheny (2020) | Cluster RCT | 2280 | 7–10 | 12 months | Daily Mile programme |

| Ketelhut (2020) | Cluster RCT | 48 | 11 | 3 months | HIIT during PE |

| Maglie (2022) | RCT | 160 | 10–11 | 6 months | PE + sports enhancement |

| Marsigliante (2023) | RCT | 310 | 8–10 | 6 months | Daily 10 min active breaks |

| Meng (2022) | RCT | 36 | 10–13 | 12 weeks | HIIT vs. moderate training |

| First Author (Year) | Intervention | Outcomes Measured | Result | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen (2015) [25] | Supporting Children’s Outcomes using Rewards, Exercise and Skills (SCORES) | Total physical activity (cpm) | 54.2 (−10.3, 118.6) | Significantly higher improvement in MVPA and cardiorespiratory fitness in the intervention group compared to control group. |

| MVPA (mins/day) | 12.7 (5.0, 20.5) | |||

| 20 m multistage fitness test (laps) | 5.4 (2.3, 8.6) | |||

| Jago (2015) | Bristol Girls Dance Project | Weekday MVPA | −1.52 [−4.76 to 1.73] | No significant difference in physical activity was observed between the two groups. |

| Mean weekend day minutes of MVPA | −1.75 [−7.51 to 4.01] | |||

| Mean weekday (CPM) | −2.44 [−25.25 to 20.38] | |||

| Mean weekend (CPM) | −4.11 [−61.07 to 52.86] | |||

| Proportion of girls meeting 60 min MVPA per weekday | −1.18 [−1.82 to 0.76] | |||

| Proportion of girls meeting 60 min MVPA per weekend day | −1.11 [−2.39 to −0.52] | |||

| Mean weekday sedentary (mins) | −6.79 [−23.60 to 10.03] | |||

| Mean weekend sedentary (mins) | 0.62 [−22.42 to 23.66] | |||

| De Greeff (2016) | MVPA | Post-intervention values | No significant difference in cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness was observed between the control and intervention group. | |

| 10 5 m shuttle run (s) | 23.3 (2.3) | |||

| 20 m shuttle run (stage) | 4.7 (2.0) | |||

| Standing broad jump (cm) | 129.7 (21.4) | |||

| Sit-ups (n) | 16.7 (4.9) | |||

| Handgrip strength (kg) | 15.8 (3.7) | |||

| Hollis (2016) | Physical Activity 4 Everyone | Changes in adiposity outcomes; mean (95% CI) | A statistically significant improvement in adiposity outcomes was seen in children complying to the physical activity program after 2 years. | |

| Weight (kg) | 61.08 (59.83, 62.34) | |||

| BMI (kg.m−2) | 21.86 (21.34, 22.37) | |||

| BMI z-score | 0.69 (0.54, 0.84) | |||

| Jarani (2016) | Exercise based physical education sessions Game-based physical education sessions | Intervention effect in exercise-based group (95% CI) | Significant improvements in physical fitness were observed after the integration of exercise-based physical education sessions in elementary school children. | |

| VO2max (ml) | 2.0 (1.5; 2.4) | |||

| 10 × 5 m shuttle run (s) | −0.9 (−1.3; −0.5) | |||

| Standing long jump (cm) | 4.2 (2.0; 6.4) | |||

| Sit-and-reach (cm) | −0.1 (−0.6; 0.4) | |||

| BMI (kg.m−2) | −0.3 (−0.5; −0.1) | |||

| Body fat (%) | −0.4 (−0.6; −0.2) | |||

| Physical activity (score) | 0.1 (0.02; 0.2) | |||

| Lubans (2016) | Active Teen Leaders Avoiding Screen-time’ (ATLAS) | Adjusted difference in change, Mean (95% CI) from baseline to 18 weeks | After an 18-month follow-up period, no significant intervention-related changes were observed in BMI, waist circumference muscle strength, or physical activity. However, the intervention significantly improved competency in resistance training skills. | |

| BMI (kg.m−2) | 0.07 (−0.34, 0.38) | |||

| BMI-z scores | 0.04 (−0.07, 0.14) | |||

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.3 (−0.7, 1.4) | |||

| Physical activity | 0.1 (−0.8, 1.0) | |||

| Grip strength (kg) | 0.3 (−0.7, 1.2) | |||

| Push-ups (repetitions) | 0.5 (−0.6, 1.6) | |||

| Resistance training skill competency | 5.9 (4.5, 7.3) | |||

| Sutherland (2016) | Physical Activity 4 Everyone | Difference between control and intervention (95% CI) | The intervention successfully enhanced students’ engagement in physical activity. | |

| MVPA | 7.0 (2.68, 11.4) | |||

| Moderate physical activity | 4.5 (2.0, 7.0) | |||

| Vigorous physical activity | 2.5 (0.3, 4.8) | |||

| Tarp (2016) [32] | Physical activity periods, recess, and homework, and active transportation | Cardiorespiratory fitness (distance, m) | 9.4 (−3.7, 22.4) | The intervention had no significant impact on cardiorespiratory fitness, physical activity, and anthropometric measures. |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.7 (−0., 2.1) | |||

| BMI | −0.1 (−0.2, 0.0) | |||

| Physical activity level (cpm) | 5 (−30, 41) | |||

| Overall MVPA (minutes/day) | 1.2 (−3.9, 6.3) | |||

| Donnelly (2017) | Academic Achievement and Physical Activity Across the Curriculum | p-value between difference in both groups post intervention | No significant difference in body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness was observed between the control and intervention group. | |

| BMI percentile | 0.08 | |||

| Waist circumference | 0.32 | |||

| PACER laps | 0.27 | |||

| Lonsdale (2017) | Activity and Motivation in Physical Education (AMPED) | Intervention-control adjusted difference in change (95% CI) | The intervention successfully enhanced students’ engagement in MVPA during lessons, demonstrating its effectiveness in promoting physical activity within structured school settings. However, its influence on leisure-time physical activity was minimal. | |

| PE lessons MVPA Sedentary Light Moderate physical activity Vigorous physical activity | Physical education lessons 5.66 (4.71 to 6.63) −11.11 (−12.63 to −9.59) 5.36 (4.46 to 6.24) 2.54 (2.07 to 3.01) 3.09 (2.48 to 3.71) | |||

| Leisure time MVPA Sedentary Light physical activity Moderate physical activity Vigorous physical activity | Leisure time −1.09 (−1.87 to −0.31) 0.92 (−0.28 to 2.13) 0.17 (−0.47 to 0.81) −0.70 (−1.17 to −0.22) −0.39 (−0.79 to 0.01) | |||

| Sutherland (2017) | Modified Supporting Children’s Outcomes using Rewards, Exercise and Skills (SCORES) | Adjusted difference between treatment group (95% CI) | No significant difference in total MVPA and moderate physical activity was observed between the two groups. However, a statistically significant increase was observed in vigorous physical activity in the intervention group. | |

| Total MVPA | 1.96 (–3.49, 7.41) | |||

| Vigorous activity | 2.19 (0.06, 4.32) | |||

| Moderate activity | –0.23 (–3.84, 3.37) | |||

| Carlin (2018) | Peer-led brisk walking intervention | Time (min/day) | p-value between difference in both groups post intervention | Increased walking during the intervention led to significant improvement in time spent in physical activity and reduced sedentary time. |

| Sedentary | 0.013 | |||

| Light physical activity | 0.018 | |||

| Moderate physical activity | 0.122 | |||

| Vigorous physical activity | 0.071 | |||

| Total physical activity | 0.007 | |||

| Have (2018) | Physical activity incorporated within mathematics lessons | Difference between control and intervention group | The physical activity intervention did not improve physical activity of body composition. | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.24 (−0.8, 0.4) | |||

| Total physical activity (count/min) | −8.6 (−69.9, 52.7) | |||

| Cardiorespiratory fitness (m) | −12.3 (−46.9, 22.4) | |||

| Ten Hoor (2018) | Strength exercise and monthly motivational sessions | Correlation between intervention and parameters as control intercept (95% CI) | After one year, the intervention group exhibited a greater reduction in fat mass compared to the control group. However, no notable differences were observed between the groups in terms of MVPA, sedentary behavior, or engagement in light physical activity. | |

| Sedentary | 0.16 (−2.8–3.2) | |||

| Light physical activity | 0.03 (−2.2–2.2) | |||

| MVPA | −0.14 (0.7–0.4) | |||

| Body fat % | 2.83 (0.1–5.6) | |||

| Body Weight (Kg) | −0.36 (−1.5–0.8) | |||

| Belton (2019) | Youth-Physical Activity Towards Health (Y-PATH) | MVPA | Effect of intervention on parameter 24.961 (18.005, 31.918) | Y-PATH school-based intervention successfully increased MVPA in the intervention patients. |

| Jago (2019) | Action 3:30R | Difference in Means (95% CI) | No significant difference between the two arms in terms of MVPA and reduced sedentary time was observed. | |

| Weekday MVPA (mins) | −0.5 (−4.57, 3.57) | |||

| Overall mean MVPA (mins) | −0.75 (−4.49, 3.00) | |||

| Mean weekday sedentary (mins) | 10.01 (−6.3, 26.31) | |||

| Leahy (2019) | High-intensity interval training | Difference in Means (95% CI) | A statistically significant improvement in adiposity outcomes and physical fitness in older adolescents was observed. | |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness (laps) | 8.9 (1.7 to 16.2) | |||

| Upper body muscular endurance (reps) | 1.7 (−1.4 to 4.7) | |||

| Lower body muscular power (cm) | 10.1 (0.3 to 19.8) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.6) | |||

| Müller (2019) | Multidimensional physical activity | Intervention effect; estimate b (95% CI) | The physical activity intervention showed significant improvement in adiposity measure; however, no significant impact on cardiorespiratory fitness was observed. | |

| Shuttle run (laps) | −0.56 (−4.67 to 3.56) | |||

| VO2max | −0.14 (−1.17 to 0.88) | |||

| BMI-z score | −0.17 (−0.24 to −0.09) | |||

| Skinfolds (mm) | −1.06 (−1.83 to −0.29) | |||

| Pfeiffer (2019) | Girls on the Move | Linear mixed coefficient (95% CI) for change in parameters following intervention | There were no significant differences in BMI-z post-intervention. However, the intervention group exhibited a smaller increase in body fat percentage and a less pronounced decline in aerobic performance compared to the control group. | |

| BMI-z scores | −0.02, (−0.05, 0.01) | |||

| Body fat % | −0.37, (−0.64, −0.10) | |||

| VO2max | 0.20, (0.03, 0.36) | |||

| Robbins (2019) | Girls on the Move | Intervention effect compared to control (95% CI) | The intervention had no significant effect on increasing time spent by young girls on MVPA. | |

| MVPA | –0.08 (–0.21, 0.05) | |||

| Seibert (2019) | CDC-based physical activity strategies | p-value between difference in both groups post intervention | The structured implementation of school-based CDC physical activity strategies did not result in greater improvements in cardiovascular fitness (CVF) compared to standard physical activity programs. | |

| PACER | 0.05 | |||

| Seljebotn (2019) | Physically active lessons, homework and recess | Mean difference between groups [95% CI] | The intervention significantly improved the time spent in physical activity; however, it had no significant impact on adiposity. | |

| Sedentary (min/day) | −13 [−26, 0] | |||

| Light activity (min/day) | −5 [−12, 3] | |||

| MVPA (min/day) | 8 [3,13] | |||

| Steps per day | 940 [341, 1540] | |||

| BMI | 0.1 [−0.4, 0.3] | |||

| Zhou (2019) | School physical education intervention, or after-school intervention, or both | Contrast coefficient between control and intervention (95% CI) | The physical activity intervention showed significant improvement in adiposity measure, cardiorespiratory fitness, and physical fitness. | |

| 20 m shuttle run (laps) | 15.2 (12.3, 18.2) | |||

| Broad jump | 17.0 (12.8, 21.3) | |||

| 50 m run (seconds) | −0.4 (−0.6, −0.3) | |||

| Sit-and-reach (cm) | 3.5 (2.5, 4.5) | |||

| T test for agility (seconds) | −1.0 (−1.2, −0.7) | |||

| 1 min sit-ups (counts) | 5.1 (3.3, 6.9); 0.16 | |||

| Plank support (seconds) | 31.8 (22.4, 41.2) | |||

| Body fat (percent) | −1.6 (−2.4, −0.8) | |||

| Breheny (2020) | The Daily Mile | Difference in adiposity between control and intervention group | The Daily Mile intervention caused no significant change in BMI z-scores and body fat % across the study population. | |

| BMI-z scores | −0.036 (−0.085 to 0.013) | |||

| Body fat % | 0.56 (−2.15 to 3.27) | |||

| Ketelhut (2020) | High-intensity interval training | Difference between control and intervention group | Students in the intervention arm have significant improvement in aerobic fitness (VO2max). | |

| AF (z-score) | 7.7 (2.3 to 13.2) | |||

| Maglie (2022) | Regular physical education and sports | p-value from baseline to post-intervention | Increased frequency and time for physical education and sports significantly improved body composition and physical activity levels in children. | |

| BMI percentile | 0.02 | |||

| Waist Circumference (cm) | <0.0001 | |||

| Vertical jump (cm) | <0.0001 | |||

| Standing broad jump (cm) | <0.0001 | |||

| Rope jumps/min | <0.0001 | |||

| Marsigliante (2023) | Daily 10 min active breaks during lessons and recess | p-value from baseline to post-intervention | Addition of daily 10 min of physical activity significantly improved body composition and physical activity levels in children | |

| BMI percentile | <0.001 | |||

| Waist Circumference (cm) | <0.001 | |||

| Standing long jump (m) | <0.0001 | |||

| Ruffier test | <0.0001 | |||

| Sit-and-reach test | <0.0001 | |||

| Meng (2022) | Group A: High-intensity interval training Group B: Moderate-intensity continuous training | Change in parameter post-intervention | Both the physical activity interventions translated to significant improvement in body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness. High-intensity interval training was slightly superior to the moderate-intensity continuous training | |

| BMI | A: 22.7 ± 1.0 B: 23.2 ± 0.7 | |||

| Body fat (%) | A: 36.2 ± 3.9 B: 34.4 ± 1.5 | |||

| Waist circumference (cm) | A: 78.8 ± 6.1 B: 78.5 ± 7.5 | |||

| VO2max | A: 47.9 ± 2.6 B: 45.6 ± 2.1 |

| Study | RS | AC | BP | BO | Attrition (Anth/Fit) | Attrition (PA/SB) | SR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen (2015) | H | H | L | L | L | L | H |

| Jago (2015) | L | L | H | L | L | L | L |

| De Greeff (2016) | U | L | H | U | U | — | L |

| Hollis (2016) | L | L | H | U | H | H | L |

| Jarani (2016) | L | L | H | H | L | — | U |

| Lubans (2016) | L | L | H | U | L | U | U |

| Sutherland (2016) | L | L | H | L | L | L | L |

| Tarp (2016) | L | L | H | U | H | H | L |

| Donnelly (2017) | L | U | H | L | H | — | H |

| Lonsdale (2017) | L | L | L | L | — | H | L |

| Sutherland (2017) | L | L | L | L | — | U | L |

| Carlin (2018) | L | L | H | H | L | — | H |

| Have (2018) | L | L | H | L | L | L | L |

| Ten Hoor (2018) | L | L | H | H | — | H | H |

| Belton (2019) | H | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| Jago (2019) | L | L | H | H | L | L | L |

| Leahy (2019) | L | L | H | H | H | — | H |

| Müller (2019) | L | H | H | H | H | — | H |

| Pfeiffer (2019) | U | L | H | U | L | H | L |

| Robbins (2019) | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Seibert (2019) | U | U | H | H | U | — | L |

| Seljebotn (2019) | L | U | H | H | L | L | H |

| Zhou (2019) | U | U | H | L | L | U | H |

| Breheny (2020) | L | L | H | L | L | — | L |

| Ketelhut (2020) | L | U | U | U | U | — | U |

| Maglie (2022) | H | U | H | U | L | L | L |

| Marsigliante (2023) | H | H | H | U | U | U | L |

| Meng (2022) | H | H | U | U | L | L | L |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gupta, S.; Lal, P. Impact of School-Based Physical Activity Intervention on Obesity and Physical Parameters in Children: A Systematic Review. Children 2026, 13, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010027

Gupta S, Lal P. Impact of School-Based Physical Activity Intervention on Obesity and Physical Parameters in Children: A Systematic Review. Children. 2026; 13(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleGupta, Surendra, and Purushottam Lal. 2026. "Impact of School-Based Physical Activity Intervention on Obesity and Physical Parameters in Children: A Systematic Review" Children 13, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010027

APA StyleGupta, S., & Lal, P. (2026). Impact of School-Based Physical Activity Intervention on Obesity and Physical Parameters in Children: A Systematic Review. Children, 13(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/children13010027