Bridging the Gap: The Role of Parent–Teacher Perception in Child Developmental Outcomes

Abstract

Highlights

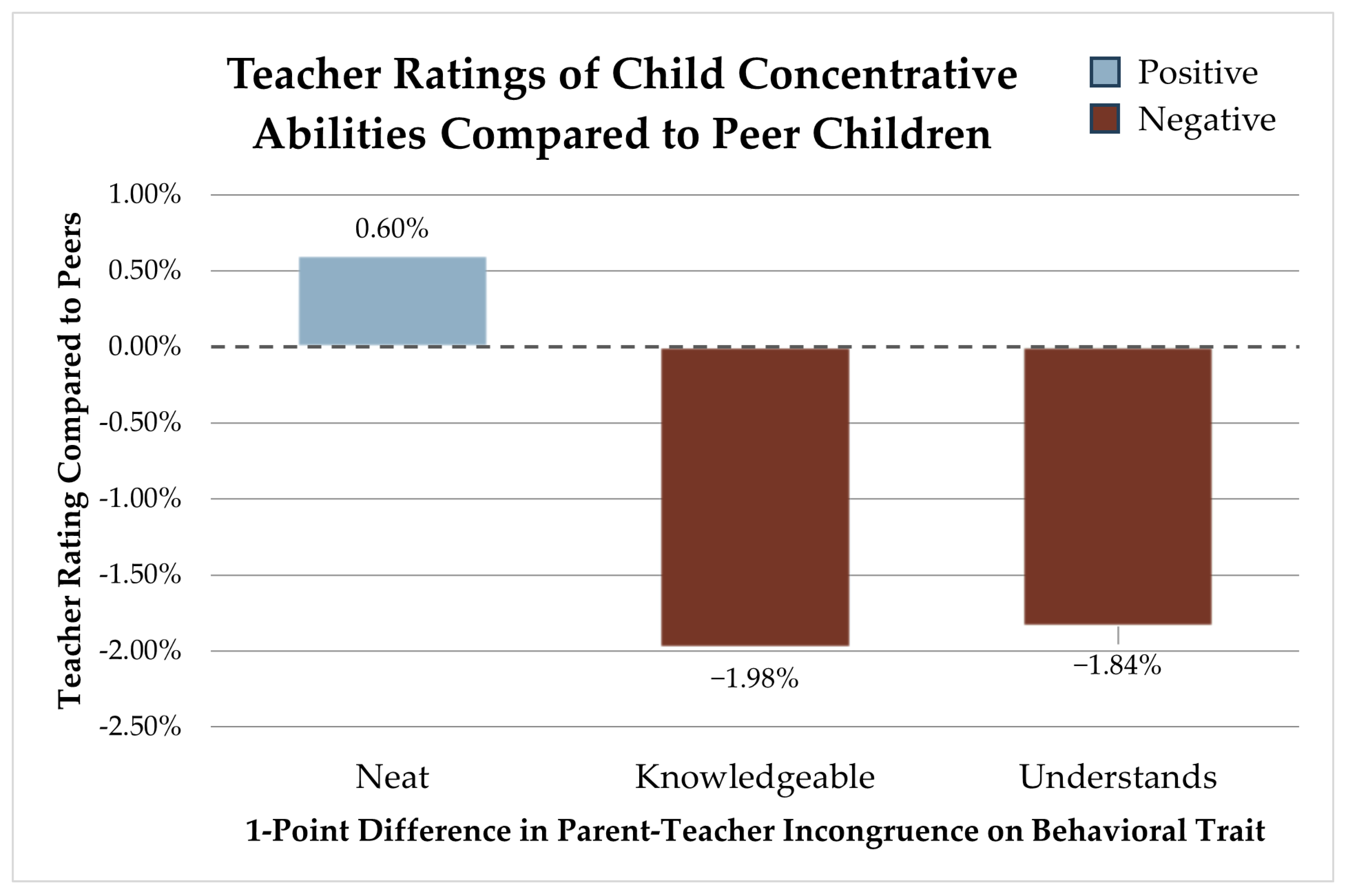

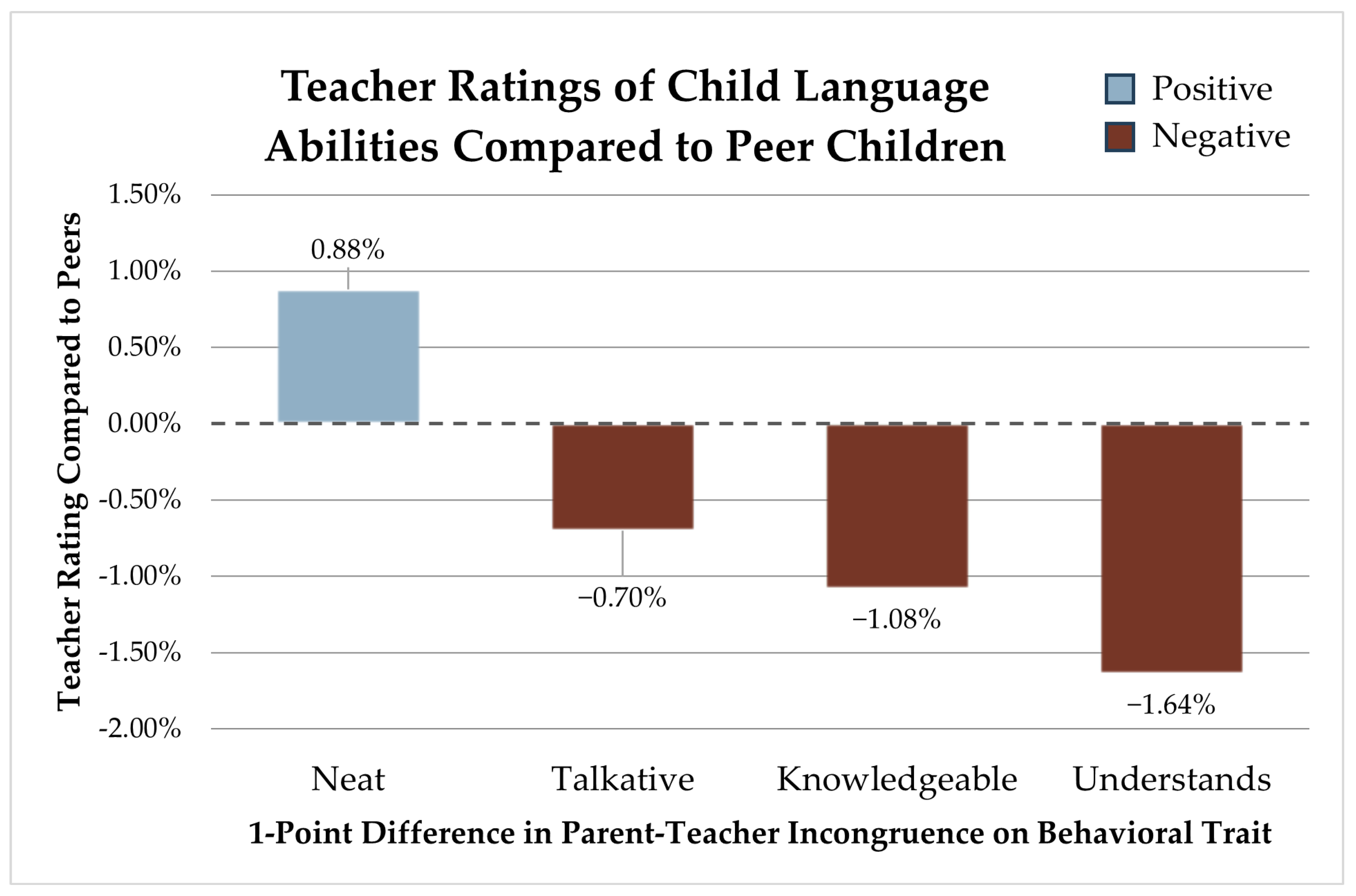

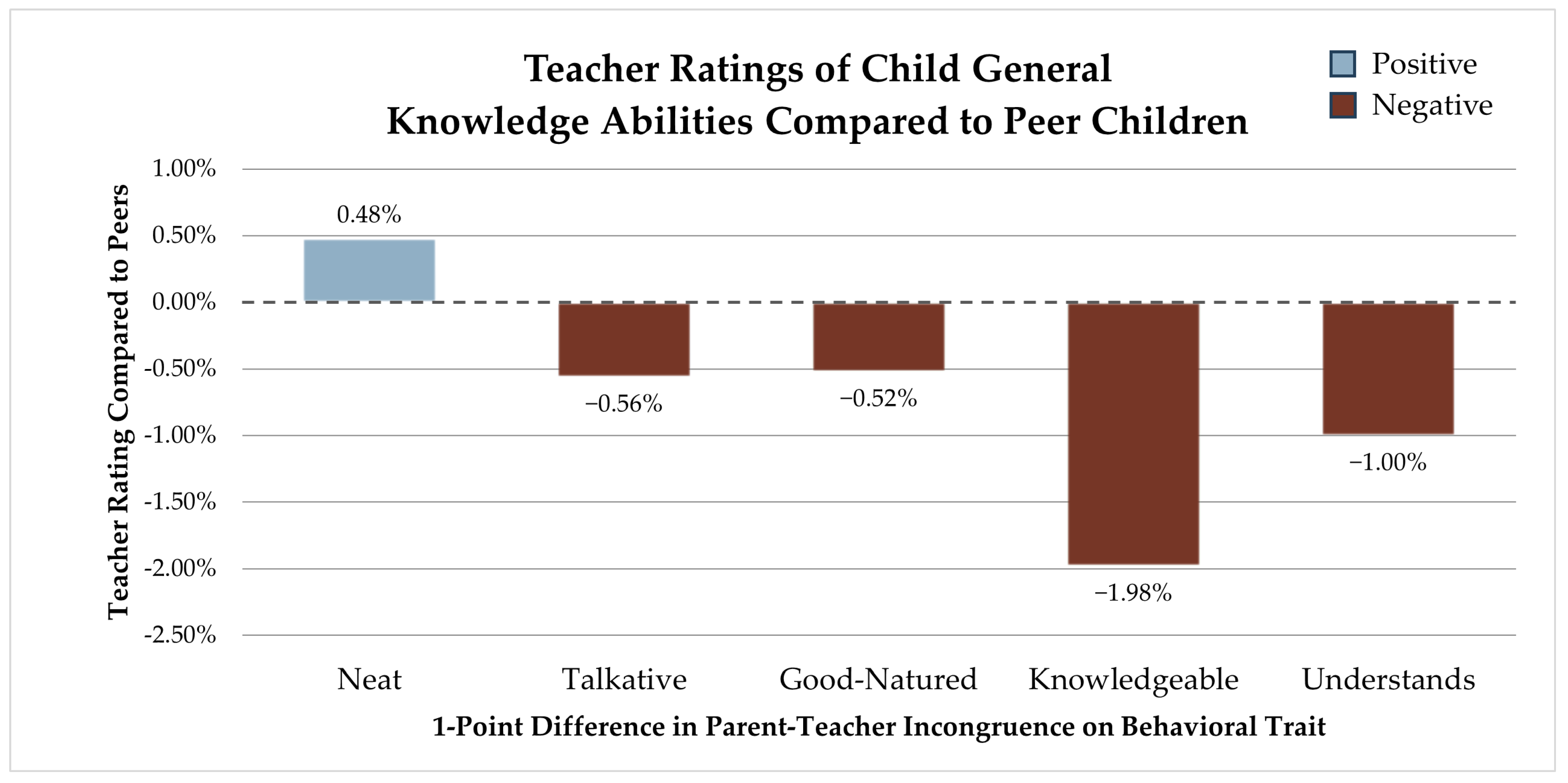

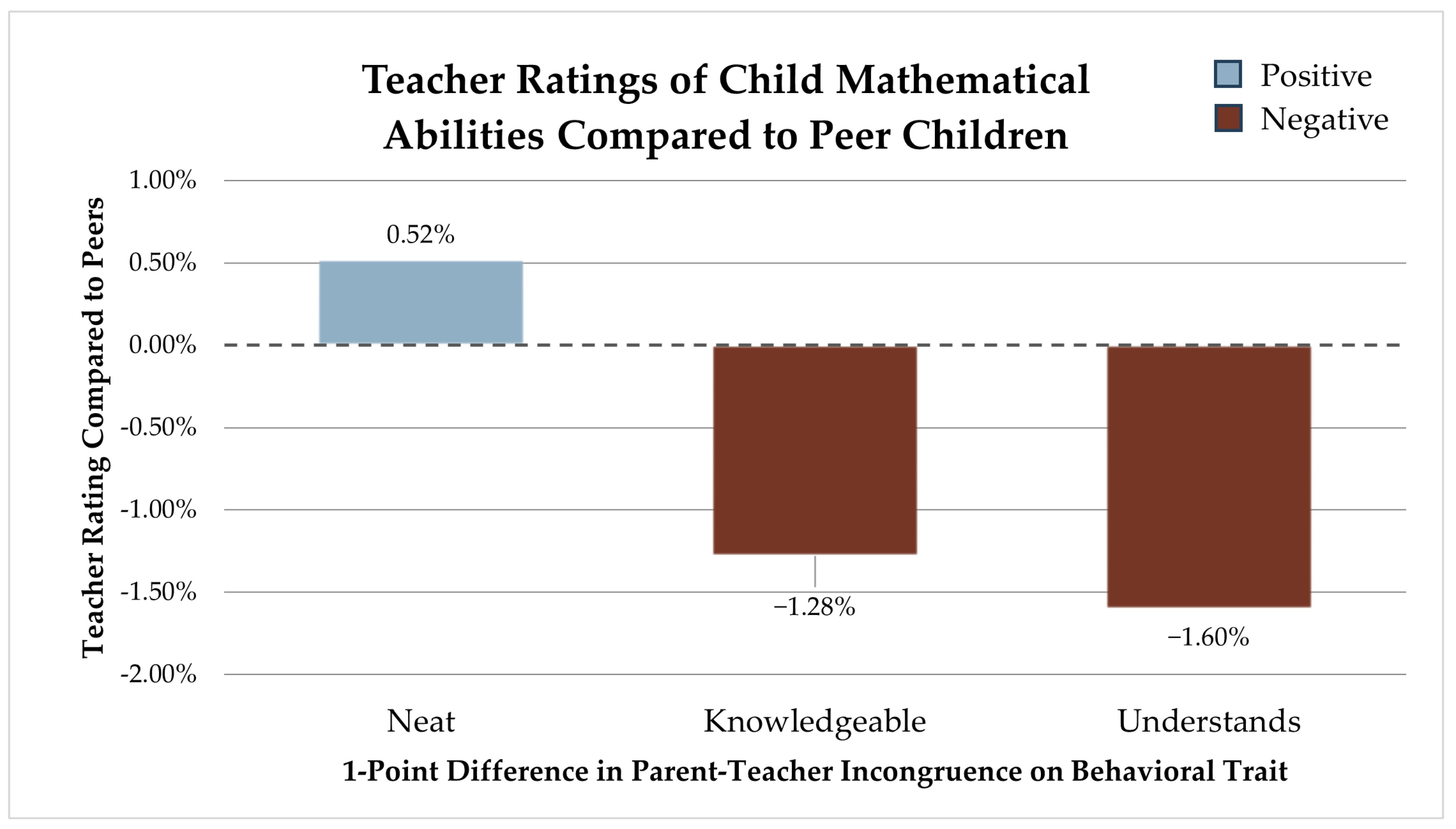

- Parent and teacher differences in perceptions of young children’s behavior regarding desire for knowledge, confidence, talkativeness, good-naturedness, and understanding are negatively associated with at least one key developmental metric (social, concentrative, general knowledgeability, linguistic, and mathematical).

- Parent and teacher differences in perceptions of a child’s behavior regarding neatness are positively associated with all five developmental metrics.

- Differences in how parents and teachers perceive child behavior are significantly associated with the development of children’s social and cognitive abilities compared to their peers. Aligning parent and teacher perceptions of children may help children reach developmental milestones in a timely manner.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Developmental Differences and Influences

1.2. Establishment of Behavior: Issues and Supportive Strategies

1.3. Parental Direct and Indirect Influences on Early Development

1.4. Educator Direct and Indirect Influences on Early Development

1.5. Parent and Teacher Perceptions Intertwined

1.6. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Social Development

3.2. Concentrative Development

3.3. Language Development

3.4. General Knowledgeability Development

3.5. Mathematical Development

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NEPS | National Educational Panel Study, Starting Cohort 2 |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares regression |

| LIfBi | Leibniz Institute of Educational Trajectories |

| KMK | Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs |

| SC 2 | National Educational Panel Study, Starting Cohort 2 |

| SE | Standard Error |

References

- Howes, C.; James, J. Children’s social development within the socialization context of childcare and early childhood education. In Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Social Development; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Jiao, D.; Tanaka, E.; Tomisaki, E.; Watanabe, T.; Sawada, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Ajmal, A.; Matsumoto, M. Development of social skills in kindergarten: A latent class growth modeling approach. Children 2021, 8, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazzelli, E.; Grazzani, I.; Pepe, A. Promoting prosocial behavior in toddlerhood: A conversation-based intervention at nursery. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2021, 204, 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, S.; Irwin, L.J.; Siddiqi, A.; Hertzman, C. The social determinants of early child development: An overview. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2010, 46, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, U.; Bryant, P. Children’s Cognitive Development and Learning; Cambridge Primary Review Trust: Northallerton, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, C.; McKinnon, R.D.; Daneri, M.P. Effect of the tools of the mind kindergarten program on children’s social and emotional development. Early Child. Res. Q. 2018, 43, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, L. Inequality in the early cognitive development of British children in the 1970 cohort. Economica 2003, 70, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, A.D.; Boyle, A.E.; Sadler, S. Parental involvement and adolescents’ educational success: The roles of prior achievement and socioeconomic status. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attig, M.; Weinert, S. What impacts early language skills? Effects of social disparities and different process characteristics of the home learning environment in the first 2 years. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 557751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.H.; Rogers, F.H. The decision to invest in child quality over quantity: Household size and household investment in education in Vietnam. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2016, 30, 104–142. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, R.T.; Garbacz, S.A.; Beattie, T.; Moore, C.L. Parent-teacher relationships in elementary school: An examination of parent-teacher trust. Psychol. Sch. 2016, 53, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Garbacz, S.A.; Sheridan, S.M.; Koziol, N.A.; Kwon, K.; Holmes, S.R. Congruence in parent–teacher communication: Implications for the efficacy of CBC for students with behavioral concerns. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 44, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence in children. Youth Soc. 1978, 9, 239–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. The contributions of the family to the development of competence in children. Schizophr. Bull. 1975, 1, 12–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rucinski, C.L.; Brown, J.L.; Downer, J.T. Teacher–child relationships, classroom climate, and children’s social-emotional and academic development. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Little, E. Behaviour Problems across Home and Kindergarten in an Australian Sample. Aust. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 5, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Phares, V.; Compas, B.E.; Howell, D.C. Perspectives on child behavior problems: Comparisons of children’s self-reports with parent and teacher reports. Psychol. Assess. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1989, 1, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, G.O.; Lengua, L.J.; McMahon, R.J. Parent involvement in school conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. J. Sch. Psychol. 2000, 38, 501–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, L.S.; Koplewicz, H.S.; Klein, R.G. Teacher ratings of hyperactivity, inattention, and conduct problems in preschoolers. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1997, 25, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, J. The reciprocal relations between teachers’ perceptions of children’s behavior problems and teacher–child relationships in the first preschool year. J. Genet. Psychol. 2011, 172, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinrad, T.L.; Gal, D.E. Fostering prosocial behavior and empathy in young children. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 20, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Weinert, S.; Wareham, H.; Law, J.; Attig, M.; von Maurice, J.; Roßbach, H. The emergence of 5-year-olds’ behavioral difficulties: Analyzing risk and protective pathways in the United Kingdom and Germany. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 769057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.M.; Russo, G.R.; Geller, P.A. The role of parental self-efficacy in parent and child well-being: A systematic review of associated outcomes. Child Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 333–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, L.; Buettner, C.K.; Snyder, A.R. Pathways from teacher depression and child-care quality to child behavioral problems. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lareau, A. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Minke, K.M.; Sheridan, S.M.; Kim, E.M.; Ryoo, J.H.; Koziol, N.A. Congruence in parent-teacher relationships: The role of shared perceptions. Elem. Sch. J. 2014, 114, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peisner-Feinberg, E.S.; Burchinal, M.R.; Clifford, R.M.; Culkin, M.L.; Howes, C.; Kagan, S.L.; Yazejian, N. The relation of preschool child-care quality to children’s cognitive and social developmental trajectories through second grade. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1534–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.; McCartney, K.; Scarr, S. Child-care quality and children’s social development. Dev. Psychol. 1987, 23, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.N.; Gleason, K.A.; Zhang, D. Relationship influences on teachers’ perceptions of academic competence in academically at-risk minority and majority first grade students. J. School Psychol. 2005, 43, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blossfeld, H.; Von Maurice, J. 2 Education as a lifelong process: The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) [Special Issue]. Z. Erzieh. 2011, 14, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Kleine, L. School entry-age effect on student’s affective–motivational attitudes in German elementary schools. Early Child. Educ. J. 2025, 53, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikus, K.; Tieben, N.; Schober, P.S. Concerted cultivation in early childhood and social inequalities in cognitive skills: Evidence from a German panel study. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2021, 72, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kårstad, S.B.; Kvello, Ø.; Wichstrøm, L.; Berg-Nielsen, T.S. What do parents know about their children’s comprehension of emotions? Accuracy of parental estimates in a community sample of pre-schoolers. Child Care Health Dev. 2014, 40, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, D.D.; Wright, D.L. Accuracy and inaccuracy in teachers’ perceptions of young children’s cognitive abilities: The role of child background and classroom context. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2011, 48, 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramling Samuelsson, I.; Björklund, C. The relation of play and learning empirically studied and conceptualised. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2023, 31, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Hughes, K.; Bosacki, S.; Rose-Krasnor, L. Is silence golden? Elementary school teachers’ strategies and beliefs regarding hypothetical shy/quiet and exuberant/talkative children. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 103, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Richmond, V.P. Quiet Children and the Classroom Teacher; ERIC: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.R.; Coll, E. From social withdrawal to social confidence: Evidence for possible pathways. Curr. Psychol. 2007, 26, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkowi, S.; Widat, F.; Wadifah, N.I.; Rohmatika, D. Increasing children’s self-confidence through parenting: Management perspective. J. Obs. J. Pendidik. Anak Usia Dini 2023, 7, 3097–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewsuwan, R.; Luster, T.; Kostelnik, M. The relation between parents’ perceptions of temperament and children’s adjustment to preschool. Early Child. Res. Q. 1993, 8, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S.P.; Sanson, A.V.; Rothbart, M.K.; Bornstein, M.H. Child temperament and parenting. In Handbook of Parenting; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, L.C.; Zakaria, A.R.; Baharun, H.; Hutagalung, F.; Sulaiman, A.M. Messy play: Creativity and imagination amount preschool children. In Interdisciplinary Behavior and Social Sciences; CRC Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, L.; Prendiville, S. Enhancing and enriching children’s learning and development through messy play. In Routledge International Handbook of Play, Therapeutic Play and Play Therapy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne, S. Messy Play in the Early Years: Supporting Learning Through Material Engagements; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, O. Emotional, behavioural, and conceptual dimensions of teacher-parent simulations. Teach. Teach. 2024, 30, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.E.; Sheridan, S.M. The effects of teacher training on teachers’ family-engagement practices, attitudes, and knowledge: A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 2019, 29, 128–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska, A. The effects of gendered parenting on child development outcomes: A systematic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, E.; McFarland-Piazza, L.; Harrison, L.J. Changing patterns of parent–teacher communication and parent involvement from preschool to school. Early Child Dev. Care 2015, 185, 1031–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, A.; Soares, I.; Rescorla, L.; Dias, P. Meta-analysis on parent–teacher agreement on preschoolers’ emotional and behavioural problems. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 52, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Developmental Ability | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Social | 3.201 | 0.911 |

| Concentration | 3.112 | 0.994 |

| Language | 3.124 | 1.020 |

| General Knowledgeability | 3.190 | 0.901 |

| Math | 3.114 | 0.869 |

| N = 2968 |

| Behavioral Trait (Prosocial) | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Talkative | 2.473 | 2.051 |

| Neat | 2.817 | 1.928 |

| Good-natured | 2.994 | 2.013 |

| Hungry for Knowledge | 2.513 | 2.078 |

| Confident | 2.817 | 2.084 |

| Sociable | 2.371 | 1.858 |

| Focused | 2.755 | 1.972 |

| Obedient | 2.774 | 1.801 |

| Understanding | 2.705 | 2.157 |

| Fearless | 2.981 | 2.056 |

| N = 2968 |

| Variable | Range | Mean/Proportion (%) | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household Size (Aggregated) | 1–6 | 3.958 | 0.964 |

| Monthly HH Income (Agg.) | 0–6 | 3.332 | 1.257 |

| Assessment of HH Economic Situation | 1–5 | 1 “Very Bad” (2.83), 2 “Rather Bad” (7.99), 3 “Partly Good” (31.20), 4 “Rather Good” (41.81), 5 “Very Good” (16.17) | Not Applicable (NA) |

| Primary Parent Employment Status | 1–4 | 1 “Full-time” (19.07), 2 “Part-time” (39.56), 3 “Side-job” (7.85), 4 “Unemployed” (33.52) | NA |

| Primary Parent Married, Lives with Spouse | 0–1 | 0 “No” (21.53), 1 “Yes” (78.47) | NA |

| Partner Child’s Bio Parent | 0–1 | 0 “No” (12.63), 1 “Yes” (87.37) | NA |

| Mother’s Age at Child’s Birth | 14–64 | 30.911 | 5.795 |

| Primary Parent Education Attainment | 9–18 | 13.613 | 2.267 |

| Partner Education Attainment | 9–18 | 13.413 | 2.362 |

| Children Face Pressure to Perform at School | 1–4 | 1 “Does Not Apply” (9.40), 2 “Does Rather Not Apply” (27.19), 3 “Does Rather Apply” (32.95), 4 “Does Apply” (30.46) | NA |

| Weaker Performance Means Less Support | 1–4 | 1 “Does Not Apply” (21.73), 2 “Does Rather Not Apply” (36.69), 3 “Does Rather Apply” (23.69), 4 “Does Apply” (17.89) | NA |

| Demands too High in Elementary School | 1–4 | 1 “Does Not Apply” (11.19), 2 “Does Rather Not Apply” (24.53), 3 “Does Rather Apply” (29.18), 4 “Does Apply” (35.11) | NA |

| Losing Fun in Learning in Elementary School | 1–4 | 1 “Does Not Apply” (37.33), 2 “Does Rather Not Apply” (39.32), 3 “Does Rather Apply” (13.24), 4 “Does Apply” (10.71) | NA |

| Importance of Preparing Child for School | 1–4 | 1 “Not Important At All” (1.82), 2 “Rather Not Important” (11.05), 3 “Rather Important” (24.29), 4 “Very Important” (62.84) | NA |

| Child Birthweight | 330–6000 | 3339.230 | 612.705 |

| Child Gender | 0–1 | 0 “Girl” (49.36), 1 “Boy” (50.64) | NA |

| N = 2968 |

| Behavior Trait | Social Coefficient (Std. Coeff.) | Concentration Coefficient (Std. Coeff.) | Language Coefficient (Std. Coeff.) | Knowledge Coefficient (Std. Coeff.) | Mathematics Coefficient (Std. Coeff.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talkative | 0.010 (0.023) | 0.012 (0.025) | −0.035 ** (−0.070) ** | −0.028 * (−0.065) * | −0.020 (−0.048) |

| Neat | 0.030 ** (0.063) ** | 0.030 *** (0.058) *** | 0.044 *** (0.083) *** | 0.024 * (0.050) * | 0.026 * (0.057) * |

| Good-Natured | 0.017 (0.038) | 0.000 (−0.001) | −0.008 (−0.016) | −0.026 ** (−0.058) ** | −0.010 (−0.024) |

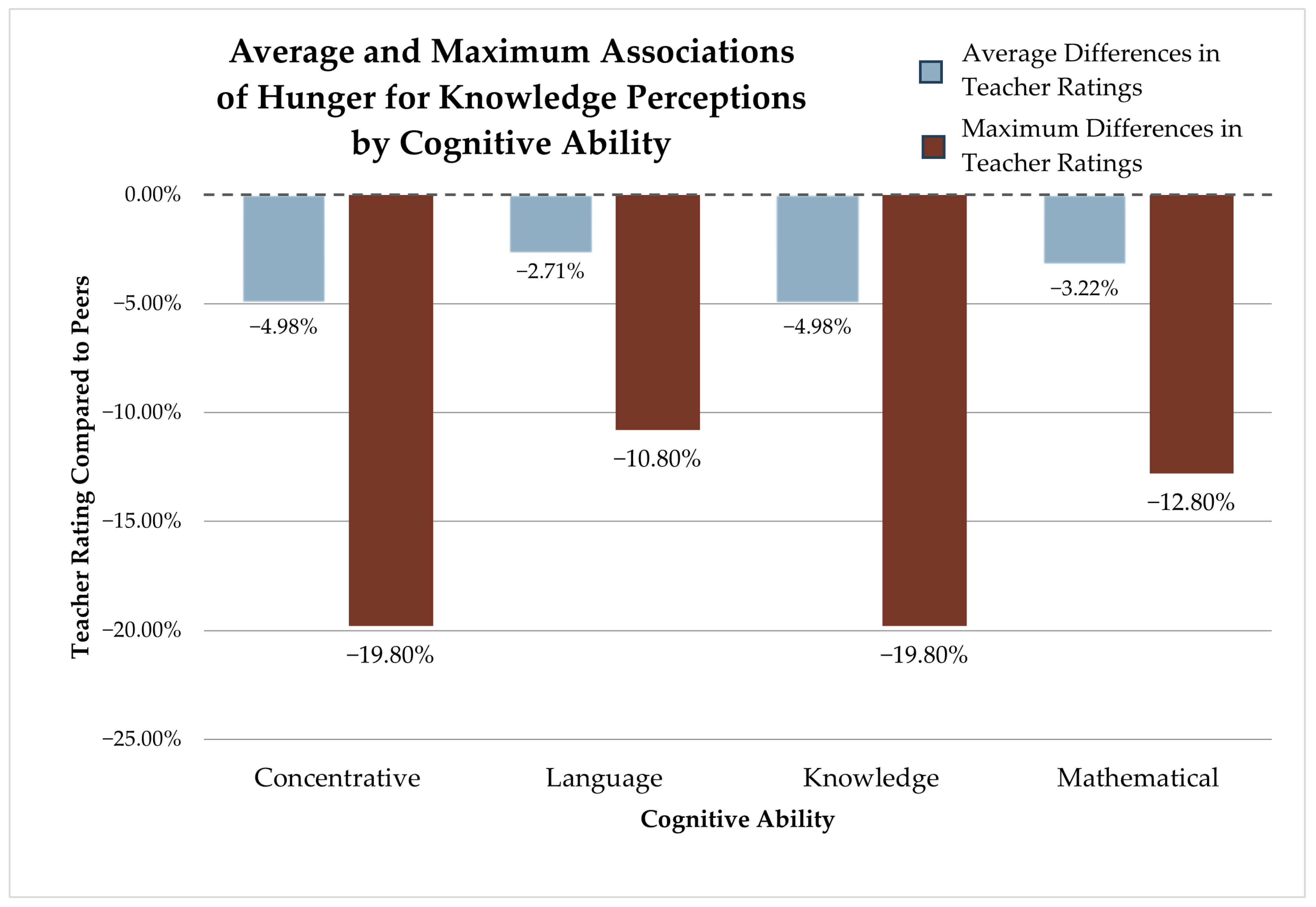

| Hungry for Knowledge | −0.073 *** (−0.162) *** | −0.099 *** (−0.204) *** | −0.054 *** (−0.109) *** | −0.099 *** (−0.225) *** | −0.064 *** (−0.151) *** |

| Confident | −0.024 * (−0.055) * | −0.013 (−0.028) | −0.009 (−0.020) | −0.016 (−0.037) | −0.005 (−0.013) |

| Sociable | −0.010 (−0.020) | −0.002 (−0.003) | −0.022 (−0.040) | −0.006 (−0.012) | 0.005 (0.011) |

| Focused | −0.004 (−0.008) | −0.004 (−0.008) | 0.013 (0.024) | −0.001 (−0.002) | 0.003 (0.006) |

| Obedient | 0.007 (0.013) | −0.010 (−0.018) | −0.019 (−0.034) | −0.007 (−0.014) | −0.001 (−0.001) |

| Understands Quickly | −0.006 (−0.014) | −0.092 *** (−0.200) *** | −0.082 *** (−0.172) *** | −0.05 *** (−0.121) *** | −0.080 *** (−0.199) *** |

| Fearless | 0.000 (−0.009) | −0.008 (0.016) | 0.016 (0.033) | 0.014 (0.033) | 0.021 (0.049) |

| N = 2968 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jensen, M.; Dufur, M.J.; Jarvis, J.A.; Pribesh, S.L. Bridging the Gap: The Role of Parent–Teacher Perception in Child Developmental Outcomes. Children 2025, 12, 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091260

Jensen M, Dufur MJ, Jarvis JA, Pribesh SL. Bridging the Gap: The Role of Parent–Teacher Perception in Child Developmental Outcomes. Children. 2025; 12(9):1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091260

Chicago/Turabian StyleJensen, McKayla, Mikaela J. Dufur, Jonathan A. Jarvis, and Shana L. Pribesh. 2025. "Bridging the Gap: The Role of Parent–Teacher Perception in Child Developmental Outcomes" Children 12, no. 9: 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091260

APA StyleJensen, M., Dufur, M. J., Jarvis, J. A., & Pribesh, S. L. (2025). Bridging the Gap: The Role of Parent–Teacher Perception in Child Developmental Outcomes. Children, 12(9), 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091260