Enhancing the Prediction of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Integrating Jeffrey Modell Foundation Criteria with Clinical Variables Using Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Study Design and Population

2.3. Machine Learning Model Development

- for k-NN, the number of neighbors (3, 5, 7, 9) and weighting scheme (‘uniform’, ‘distance’);

- for SVM, the regularization parameter C (0.1, 1, 10), kernel type (‘linear’, ‘rbf’), and kernel coefficient gamma (‘scale’, ‘auto’);

- for RF, the number of estimators (100, 200, 500), maximum depth (None, 10, 20), and the number of features considered at each split (‘sqrt’, ‘log2’);

- for NB, the smoothing parameter var_smoothing (1 × 10−9, 1 × 10−8, 1 × 10−7).

2.4. Model Evaluation and Performance Metrics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Clinical and JMF Features of Participants

3.3. The Performance of Machine Learning Models

3.3.1. Accuracy

3.3.2. F1 Score

3.3.3. Sensitivity

3.3.4. Specificity

3.3.5. Youden Index

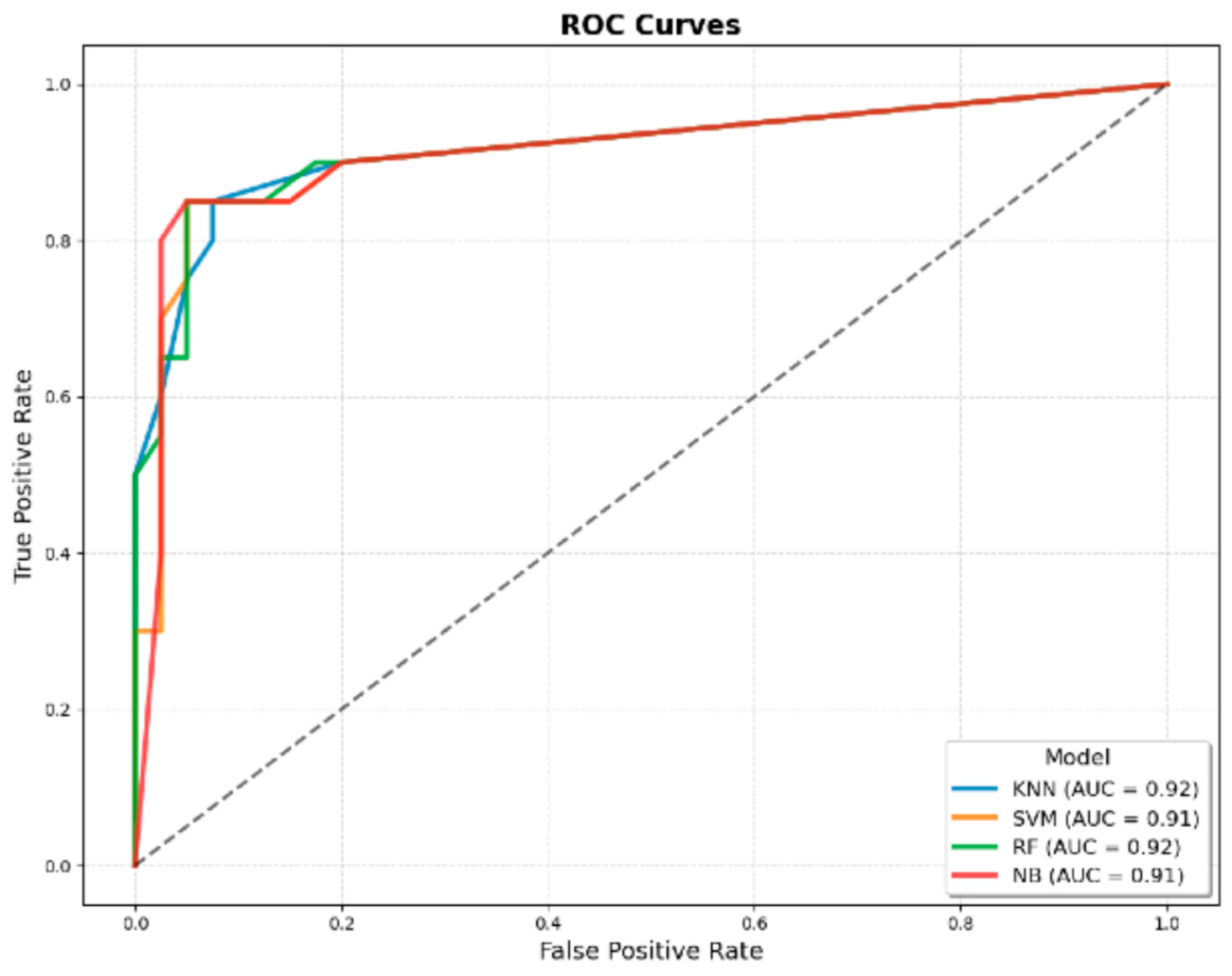

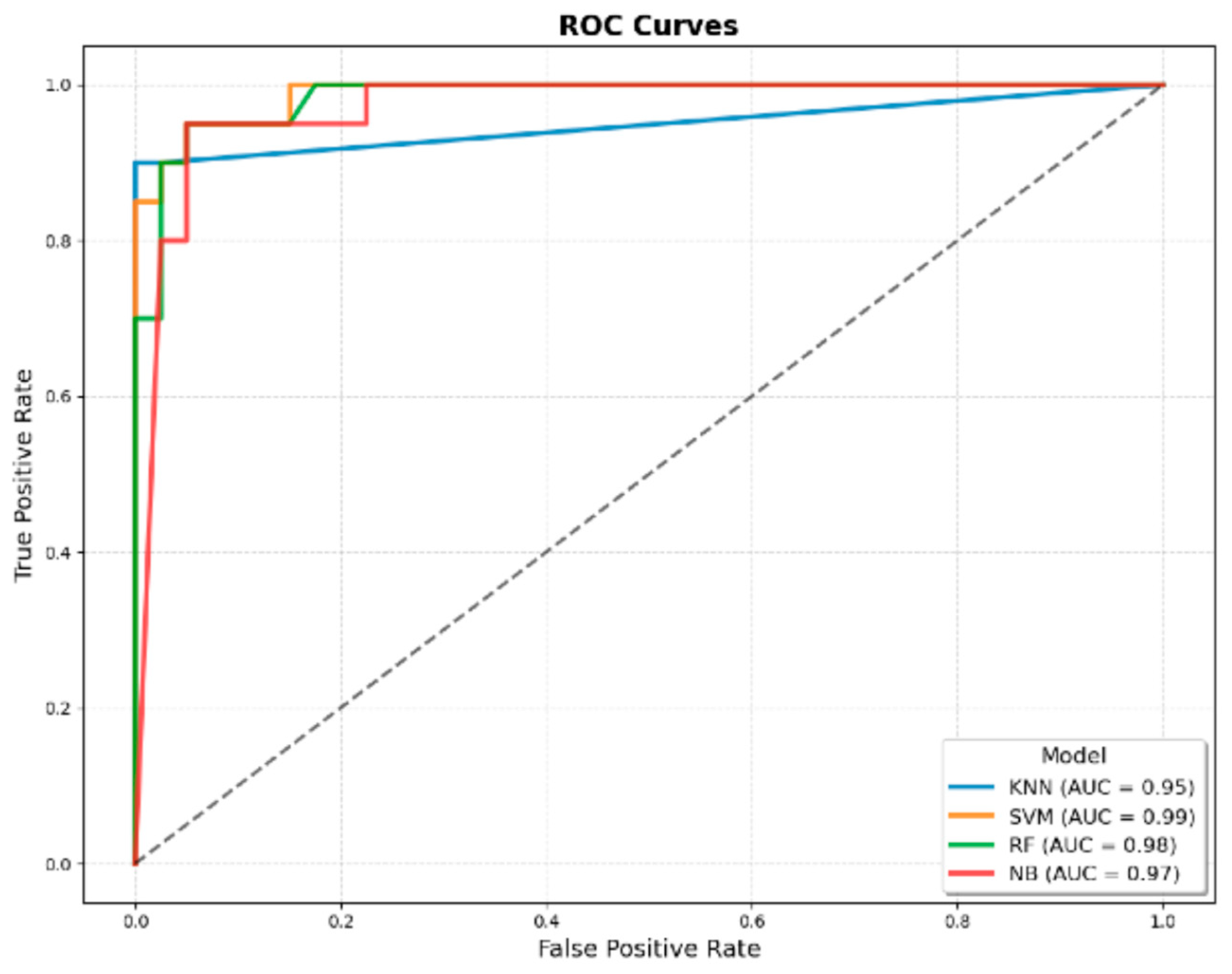

3.3.6. AUROC

3.3.7. Comparison of the Classical JMF Criteria with the Best-Performing JMF-Based ML Model

3.3.8. Comparison of the Best JMF-Based ML Model with the Best Integrated Model (JMF + Additional Clinical Variables)

3.3.9. Comparison of the Classical JMF Criteria with the Best Integrated Model (JMF + Additional Clinical Variables)

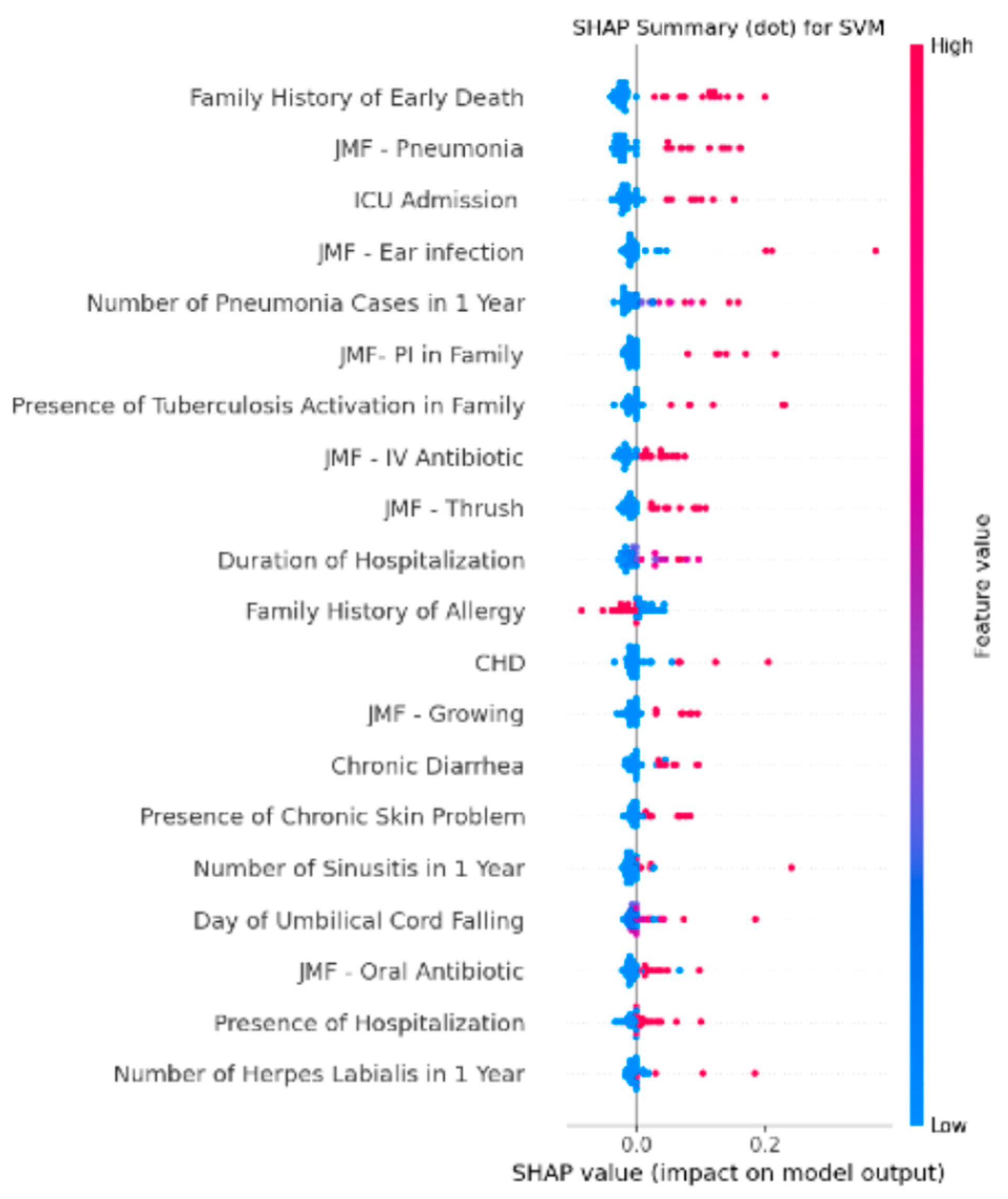

3.4. Feature Importance Analysis of the Integrated SVM Model Using SHAP Values

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tangye, S.; Al-Herz, W.; Bousfiha, A.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Franco, J.; Holland, S.; Klein, C.; Morio, T.; Oksenhendler, E.; Picard, C.; et al. Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2022 Update on the Classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 42, 1473–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, M.C.; AI Bousfiha, A.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Hambleton, S.; Klein, C.; Morio, T.; Picard, C.; Puel, A.; Rezaei, N.; Seppanen, M.R. Human inborn errors of immunity: 2024 Update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J. Hum. Immunol. 2025, 1, e20250003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousfiha, A.; Jeddane, L.; Ailal, F.; Casanova, J.; Abel, L. Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Worldwide: More Common than Generally Thought. J. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 34, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, J.; Buckley, R. Population prevalence of diagnosed primary immunodeficiency diseases in the United States. J. Clin. Immunol. 2007, 27, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolhassani, H.; Azizi, G.; Sharifi, L.; Yazdani, R.; Mohsenzadegan, M.; Delavari, S.; Sohani, M.; Shirmast, P.; Chavoshzadeh, Z.; Mahdaviani, S.; et al. Global systematic review of primary immunodeficiency registries. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 16, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsink, K.; van Montfrans, J.; van Gijn, M.; Blom, M.; van Hagen, P.; Kuijpers, T.; Frederix, G. Cost and impact of early diagnosis in primary immunodeficiency disease: A literature review. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 213, 108359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeniz, F.; Gul, Y.; Yorulmaz, A.; Guner, S.; Keles, S.; Reisli, I. Evaluation of the 10 Warning Signs in Primary and Secondary Immunodeficient Patients. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 900055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahn, V. The infection susceptible child. HNO 2000, 48, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmand, S.; Baumann, U.; von Bernuth, H.; Borte, M.; Foerster-Waldl, E.; Franke, K.; Habermehl, P.; Kapaun, P.; Klock, G.; Liese, J.; et al. Interdisciplinary AWMF Guideline for the Diagnostics of Primary Immunodeficiency. Klin. Padiatr. 2011, 223, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankisch, P.; Schiffner, J.; Ghosh, S.; Babor, F.; Borkhardt, A.; Laws, H. The Duesseldorf Warning Signs for Primary Immunodeficiency: Is it Time to Change the Rules? J. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 35, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarangelo, L. Primary immunodeficiencies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, S182–S194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamee, M.; Azizi, G.; Baris, S.; Karakoc-Aydiner, E.; Ozen, A.; Kiliç, S.; Kose, H.; Chavoshzadeh, Z.; Mahdaviani, S.; Momen, T.; et al. Clinical, immunological, molecular and therapeutic findings in monogenic immune dysregulation diseases: Middle East and North Africa registry. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 244, 109131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, S.; Ucar, R.; Caliskaner, A.; Reisli, I.; Guner, S.; Sayar, E.; Baloglu, I. How effective are the 6 European Society of Immunodeficiency warning signs for primary immunodeficiency disease? Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016, 116, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkwright, P.; Gennery, A. Ten warning signs of primary immunodeficiency: A new paradigm is needed for the 21st century. In Year in Human and Medical Genetics: Inborn Errors of Immunity I; NIH: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2011; pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madabhushi, A.; Lee, G. Image analysis and machine learning in digital pathology: Challenges and opportunities. Med. Image Anal. 2016, 33, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, E.; Sahin, A.; Babayev, H.; Gül, M.; Batur, A.; Kaynar, M.; Kiliç, Ö.; Göktas, S. Machine learning algorithm predicts urethral stricture following transurethral prostate resection. World J. Urol. 2024, 42, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altıntaş, E.; Şahin, A.; Erol, S.; Özer, H.; Gül, M.; Batur, A.F.; Kaynar, M.; Kılıç, Ö.; Göktaş, S. Navigating the gray zone: Machine learning can differentiate malignancy in PI-RADS 3 lesions. In Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. S1078-1439(24)00645-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Song, J.; Sun, S.; Zhu, K.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Guo, C.; Xiang, W.; Tong, Y.; Zeng, M.; et al. Immune signatures predict response to house dust mite subcutaneous immunotherapy in patients with allergic rhinitis. Allergy 2024, 79, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, I.; Groshenkov, K.; Sigalov, G. Food anaphylaxis diagnostic marker compilation in machine learning design and validation. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothalawala, D.; Murray, C.; Simpson, A.; Custovic, A.; Tapper, W.; Arshad, S.; Holloway, J.; Rezwan, F.; Investigators, S.U. Development of childhood asthma prediction models using machine learning approaches. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2021, 11, e12076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, N.; Coffey, M.; Kurian, A.; Quinn, J.; Orange, J.; Modell, V.; Modell, F. A validated artificial intelligence-based pipeline for population-wide primary immunodeficiency screening. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 151, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, J.; Guzman, S.; Cascajares, E.; Garabedian, E.; Fuleihan, R.; Sullivan, K.; Reyes, S. Who’s your data? Primary immune deficiency differential diagnosis prediction via machine learning and data mining of the USIDNET registry. J. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 42, S7–S8. [Google Scholar]

- Mayampurath, A.; Ajith, A.; Anderson-Smits, C.; Chang, S.; Brouwer, E.; Johnson, J.; Baltasi, M.; Volchenboum, S.; Devercelli, G.; Ciaccio, C. Early Diagnosis of Primary Immunodeficiency Disease Using Clinical Data and Machine Learning. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.-Pract. 2022, 10, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Features | Overall | IEI | Non-IEI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, (n, %) | 298 (100) | 98 (32.8) | 200 (67.2) | - | |

| Age (month), (mean ± SD) | 74.93 ± 62.59 [68.43–81.44] | 98.87 ± 66.37 [85.56–112.17] | 65.46 ± 63.71 [56.53–74.38] | <0.001 α | |

| Sex | Female, (n, %) | 146 (48.99) | 48 (48.98) | 98 (49) | ns α |

| Male, (n, %) | 152 (51.01) | 50 (51.02) | 102 (51) | ||

| JMF Warning Signs | |||||

| ≥4 new ear infections within 1 year, (n, %) | 9 (3.02) | 8 (8.16) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001 α | |

| ≥2 serious sinus infections within 1 year, (n, %) | 11 (3.69) | 9 (9.18) | 2 (1) | <0.001 α | |

| ≥2 months on antibiotics with little effect, (n, %) | 53 (17.79) | 45 (45.92) | 8 (4) | <0.001 α | |

| ≥2 pneumonias within 1 year, (n, %) | 70 (23.49) | 63 (64.29) | 7 (3.5) | <0.001 α | |

| Failure of an infant to gain weight or grow normally, (n, %) | 40 (13.42) | 37 (37.76) | 3 (1.5) | <0.001 α | |

| Recurrent, deep skin or organ abscesses, (n, %) | 10 (3.36) | 9 (9.18) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001 α | |

| Persistent thrush in mouth or fungal infection on skin, (n, %) | 55 (18.46) | 43 (43.88) | 12 (6) | <0.001 α | |

| Need for IV antibiotics to clear infections, (n, %) | 111 (37.25) | 81 (82.65) | 30 (15) | <0.001 α | |

| ≥2 deep-seated infections including septicemia, (n, %) | 10 (3.36) | 9 (9.18) | 1 (0.5) | <0.001 α | |

| Family history of IEI, (n, %) | 29 (9.73) | 25 (25.51) | 4 (2) | <0.001 α | |

| Total JMF points, (mean ± SD) [95% CI] | 1.34 ± 1.78 [1.13–1.54] | 3.37 ± 1.66 [3.03–3.7] | 0.34 ± 0.61 [0.25–0.43] | <0.001 β | |

| Additional Clinical Data | |||||

| Presence of Hospitalization, (n, %) | 130 (43.62) | 86 (87.76) | 44 (12.24) | <0.001 α | |

| Number of Hospitalizations, (mean ± SD) [95% CI] | 7.07 ± 18.68 [4.93–9.21] | 12.83 ± 25.42 [7.73–17.92] | 4.25 ± 13.47 [2.36–6.13] | <0.001 β | |

| Duration of Hospitalization, (mean ± SD) [95% CI] | 4.87 ± 6.33 [4.15–5.6] | 10.69 ± 7.43 [9.2–12.18] | 2.02 ± 2.85 [1.62–2.42] | <0.001 β | |

| Number of Otitis in 1 Year, (mean ± SD) [95% CI] | 0.42 ± 1.37 [0.26–0.57] | 1.07 ± 2.16 [0.64–1.5] | 0.1 ± 0.47 [0.03–0.16] | <0.001 β | |

| Number of Sinusitis in 1 Year, (mean ± SD) [95% CI] | 0.24 ± 0.94 [0.13–0.35] | 0.59 ± 1.38 [0.31–0.87] | 0.07 ± 0.54 [-0.01–0.15] | <0.001 β | |

| Number of Pneumonia in 1 Year, (mean ± SD) [95% CI] | 1.37 ± 2.58 [1.07–1.66] | 3.65 ± 3.42 [2.97–4.34] | 0.25 ± 0.6 [0.17–0.33] | <0.001 β | |

| Number of Herpes Labialis in 1 Year, (mean ± SD) [95% CI] | 0.39 ± 1.52 [0.21–0.56] | 1.12 ± 2.49 [0.62–1.62] | 0.03 ± 0.19 [0–0.05] | <0.001 β | |

| Vaccination Related Complications, (n, %) | 8 (2.68) | 6 (6.12) | 2 (1) | <0.05 α | |

| Discharge After BCG Vaccination, (n, %) | 5 (1.68) | 3 (3.06) | 2 (1) | ns α | |

| Lymphadenopathy After BCG Vaccination, (n, %) | 3 (1.01) | 3 (1.01) | 0 (0) | <0.05 α | |

| Presence of Chronic Skin Problem, (n, %) | 55 (18.46) | 44 (44.9) | 11 (5.5) | <0.001 α | |

| Day of Umbilical Cord Falling, (mean ± SD) [95% CI] | 7.58 ± 3.28 [7.2–7.95] | 7.1 ± 2.32 [6.77–7.42] | 8.56 ± 4.52 [7.66–9.47] | <0.001 β | |

| Delay in Milk Tooth Shedding, (n, %) | 16 (5.37) | 12 (12.24) | 4 (2) | <0.001 α | |

| Delay in Wound Healing, (n, %) | 35 (11.74) | 29 (29.59) | 6 (3) | <0.001 α | |

| Convulsion, (n, %) | 26 (8.72) | 20 (20.41) | 6 (3) | <0.001 α | |

| CHD, (n, %) | 23 (7.72) | 21 (21.43) | 2 (1) | <0.001 α | |

| Chronic Diarrhea, (n, %) | 34 (11.41) | 28 (28.57) | 6 (3) | <0.001 α | |

| ICU Admission, (n, %) | 49 (16.44) | 43 (43.88) | 6 (3) | <0.001 α | |

| Presence of Consanguinity Between Parents, (n, %) | 21 (7.05) | 16 (16.33) | 5 (2.5) | <0.001 α | |

| Degree of Consanguinity, (mean ± SD) [95% CI] | 0.28 ± 0.69 [0.2–0.36] | 0.57 ± 0.86 [0.4–0.74] | 0.14 ± 0.53 [0.06–0.21] | <0.001 β | |

| Family History of Early Death, (n, %) | 77 (25.84) | 66 (67.35) | 11 (5.5) | <0.001 α | |

| Presence of Tuberculosis Activation in Family, (n, %) | 21 (7.05) | 16 (16.33) | 5 (2.5) | <0.001 α | |

| Family History of CHD, (n, %) | 25 (8.39) | 11 (11.22) | 14 (7) | ns α | |

| Family History of Autoimmunity, (n, %) | 51 (17.11) | 28 (28.57) | 23 (11.5) | <0.001 α | |

| Family History of Allergy, (n, %) | 129 (43.29) | 31 (31.63) | 98 (49) | <0.05 α | |

| Family History of Cancer, (n, %) | 52 (17.45) | 28 (28.57) | 24 (12) | <0.001 α | |

| Total JMF Points | Overall | IEI | Non-IEI | p Value α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 points | 148 (49.66) | 2 (2.04) | 146 (73) | <0.001 |

| 1 points | 51 (17.11) | 10 (10.2) | 41 (20.5) | |

| 2 points | 34 (11.41) | 22 (22.45) | 12 (6) | |

| 3 points | 21 (7.05) | 19 (19.39) | 1 (0.5) | |

| 4 points | 20 (6.71) | 21 (21.43) | 0 (0) | |

| 5 points | 13 (4.36) | 13 (13.27) | 0 (0) | |

| 6 points | 7 (2.35) | 7 (7.14) | 0 (0) | |

| 7 points | 4 (1.34) | 4 (4.08) | 0 (0) | |

| 8 points | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 9 points | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 10 points | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Classical JMF Criteria | ML Models (Using Only JMF Features) | ML Models (Using JMF + Additional Features) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metrics | Threshold-Based Scoring | KNN | SVM | RF | NB | KNN | SVM | RF | NB |

| Accuracy | 0.91 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 0.94 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.03 |

| Sensitivity | 0.87 | 0.83 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.73 ± 0.10 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 0.97 ± 0.03 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 0.93 ± 0.04 |

| Specificity | 0.93 | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 0.94 ± 0.04 |

| F1 Score | 0.87 | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 0.86 ± 0.05 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.07 | 0.71 ± 0.07 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.89 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.04 |

| Youden Index | 0.81 | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 0.81 ± 0.07 | 0.77 ± 0.08 | 0.68 ± 0.10 | 0.56 ± 0.08 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 0.86 ± 0.05 |

| AUROC | 0.90 | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 0.99 ± 0.00 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.97 ± 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yorulmaz, A.; Şahin, A.; Sonmez, G.; Eldeniz, F.C.; Gül, Y.; Karaselek, M.A.; Güler, Ş.N.; Keleş, S.; Reisli, İ. Enhancing the Prediction of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Integrating Jeffrey Modell Foundation Criteria with Clinical Variables Using Machine Learning. Children 2025, 12, 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091259

Yorulmaz A, Şahin A, Sonmez G, Eldeniz FC, Gül Y, Karaselek MA, Güler ŞN, Keleş S, Reisli İ. Enhancing the Prediction of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Integrating Jeffrey Modell Foundation Criteria with Clinical Variables Using Machine Learning. Children. 2025; 12(9):1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091259

Chicago/Turabian StyleYorulmaz, Alaaddin, Ali Şahin, Gamze Sonmez, Fadime Ceyda Eldeniz, Yahya Gül, Mehmet Ali Karaselek, Şükrü Nail Güler, Sevgi Keleş, and İsmail Reisli. 2025. "Enhancing the Prediction of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Integrating Jeffrey Modell Foundation Criteria with Clinical Variables Using Machine Learning" Children 12, no. 9: 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091259

APA StyleYorulmaz, A., Şahin, A., Sonmez, G., Eldeniz, F. C., Gül, Y., Karaselek, M. A., Güler, Ş. N., Keleş, S., & Reisli, İ. (2025). Enhancing the Prediction of Inborn Errors of Immunity: Integrating Jeffrey Modell Foundation Criteria with Clinical Variables Using Machine Learning. Children, 12(9), 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091259