Let’s Learn About Emotions Program: Acceptability, Fidelity, and Students’ Mental Well-Being Outcomes for Finnish Primary School Children

Abstract

Highlights

- The Let’s Learn About Emotions program was found to be highly acceptable to students, parents, teachers, and principals, and was delivered with high fidelity by classroom teachers.

- Parent reports indicated improvements in children’s conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems, while student self-reports did not show similar benefits.

- The program is feasible, culturally appropriate, and suitable for implementation in Finnish schools, though refinements could further enhance its impact.

- Future research with a control design is needed to rigorously test effectiveness.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Intervention

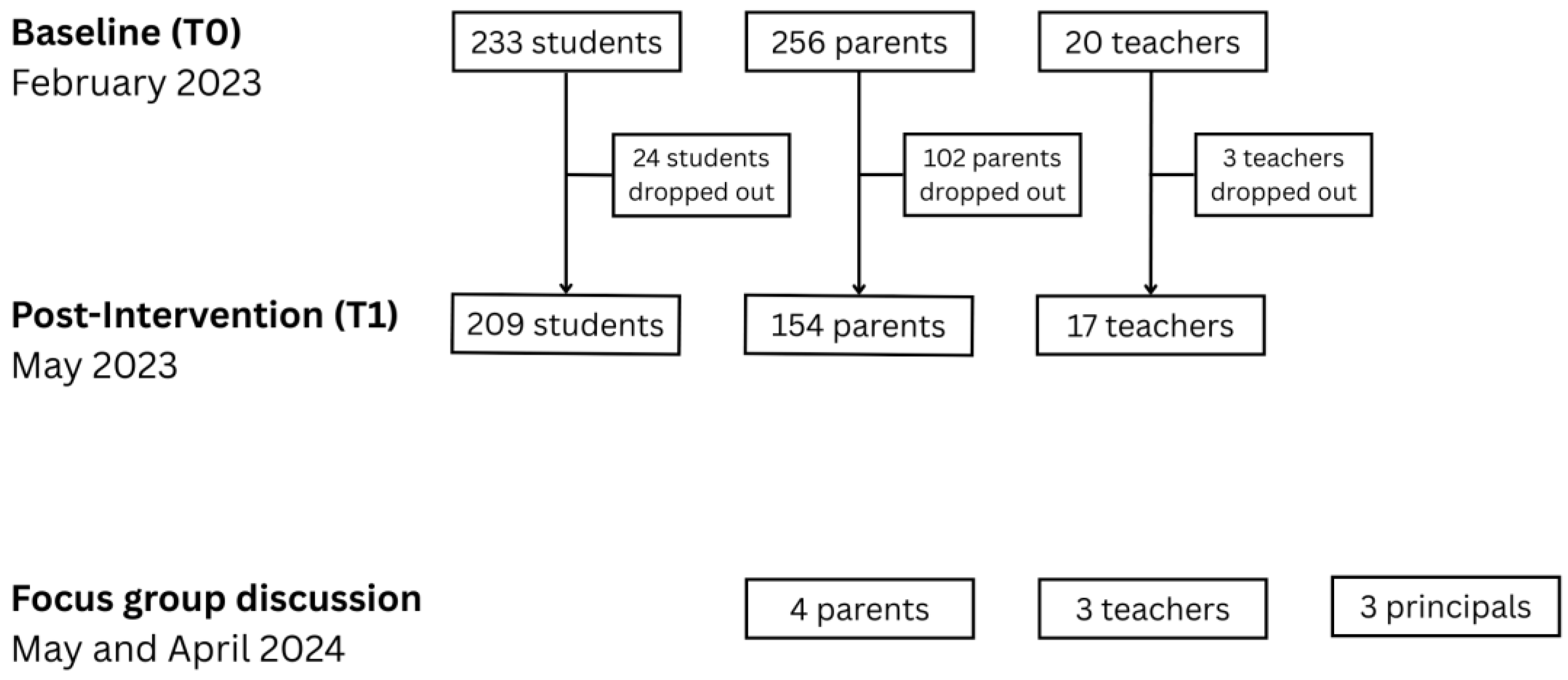

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Acceptability

2.4.2. Fidelity

2.4.3. Early Efficacy Outcomes

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Acceptability of the Program: Quantitative Results

3.2. Acceptability of the Program: Qualitative Results

3.3. Fidelity

3.4. Changes in Students’ Mental Well-Being

3.5. Emotional Awareness Knowledge

| Outcome | Mean T0 | Mean T1 | Mean Difference (T1–T0) | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% CI 1 of the Difference | t | df | Two-Sided p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||||

| Child | SDQ 2 total | 9.40 | 9.92 | 0.524 | 4.225 | 0.294 | −0.056 | 1.105 | 1.781 | 205 | 0.076 |

| SDQ emotional | 3.00 | 3.10 | 0.107 | 2.069 | 0.144 | −0.177 | 0.391 | 0.741 | 205 | 0.460 | |

| SDQ conduct | 1.68 | 1.87 | 0.189 | 1.478 | 0.103 | −0.014 | 0.392 | 1.839 | 205 | 0.067 | |

| SDQ hyperactivity | 3.04 | 3.32 | 0.277 | 1.660 | 0.116 | 0.049 | 0.505 | 2.392 | 205 | 0.018 | |

| SDQ peer relationships | 1.68 | 1.63 | −0.049 | 1.264 | 0.088 | −0.222 | 0.125 | −0.551 | 205 | 0.582 | |

| SDQ prosocial | 8.07 | 7.81 | −0.257 | 1.471 | 0.102 | −0.459 | −0.055 | −2.511 | 205 | 0.013 | |

| SDQ perceived difficulties | 0.61 | 0.43 | −0.181 | 1.221 | 0.134 | −0.447 | 0.086 | −1.348 | 82 | 0.181 | |

| Friendships | 1.16 | 1.08 | 0.019 | 0.530 | 0.037 | −0.053 | 0.092 | 0.524 | 206 | 0.601 | |

| Loneliness | 2.76 | 2.78 | −0.073 | 0.857 | 0.060 | −0.191 | 0.045 | −1.222 | 204 | 0.223 | |

| CBC 3 total | 7.63 | 7.74 | 0.103 | 2.765 | 0.199 | −0.288 | 0.495 | 0.519 | 193 | 0.604 | |

| Bullying victimization | 0.82 | 0.76 | −0.059 | 1.157 | 0.081 | −0.220 | 0.101 | −0.729 | 201 | 0.467 | |

| School environment | 15.43 | 14.71 | −0.724 | 2.899 | 0.207 | −1.133 | −0.316 | −3.498 | 195 | <0.001 | |

| Parent | SDQ total | 8.65 | 7.67 | 0.082 | 1.620 | 0.134 | −0.182 | 0.346 | 0.611 | 146 | 0.542 |

| SDQ emotional | 1.84 | 1.46 | −0.102 | 1.204 | 0.099 | −0.298 | 0.094 | −1.028 | 146 | 0.306 | |

| SDQ conduct | 1.65 | 1.46 | −0.313 | 1.642 | 0.135 | −0.581 | −0.045 | −2.311 | 146 | 0.022 | |

| SDQ hyperactivity | 3.34 | 3.03 | −0.374 | 1.361 | 0.112 | −0.596 | −0.152 | −3.333 | 146 | 0.001 | |

| SDQ peer relationships | 1.82 | 1.72 | −0.190 | 1.094 | 0.090 | −0.369 | −0.012 | −2.111 | 146 | 0.036 | |

| SDQ prosocial | 7.58 | 7.66 | −0.017 | 1.613 | 0.210 | −0.437 | 0.404 | −0.081 | 58 | 0.936 | |

| SDQ perceived difficulties | 1.46 | 1.44 | −0.980 | 3.078 | 0.254 | −1.481 | −0.478 | −3.859 | 146 | <0.001 | |

| Child’s friendships | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.034 | 0.395 | 0.033 | −0.030 | 0.098 | 1.043 | 146 | 0.299 | |

| Child’s loneliness | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.014 | 0.261 | 0.022 | −0.029 | 0.056 | 0.631 | 146 | 0.529 | |

| Teacher | CBC total | 13.69 | 12.44 | −1.250 | 3.152 | 0.788 | −2.929 | 0.429 | −1.586 | 15 | 0.133 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| SEL | Social and Emotional Learning |

| PPI | Positive Psychology |

| Up2-D2 | Universal Unified Prevention Program for Diverse Disorders |

| SDQ | The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

| CBC | Classroom Behavioral Climate |

References

- Sourander, A.; Jensen, P.; Davies, M.; Niemelä, S.; Elonheimo, H.; Ristkari, T.; Helenius, H.; Sillanmäki, L.; Piha, J.; Kumpulainen, K.; et al. Who is at greatest risk of adverse long-term outcomes? The Finnish from a boy to a man study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 46, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, E.; Morin, A.J.S.; Langlois, J.; Tardif-Grenier, K.; Archambault, I. Internalizing and externalizing behavior problems and student engagement in elementary and secondary school students. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 2327–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickersham, A.; Sugg, H.V.; Epstein, S.; Stewart, R.; Ford, T.; Downs, J. Systematic review and meta-analysis: The association between child and adolescent depression and later educational attainment. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. How School Systems Can Improve Health and Well-Being: Topic Brief: Mental Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240064751 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Manassis, K. Anxiety prevention in schools. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaoude, G.J.A.; Leiva-Granados, R.; Mcgranahan, R.; Callaghan, P.; Haghparast-Bidgoli, H.; Basson, L.; Ebersöhn, L.; Gu, Q.; Skordis, J. Universal primary school interventions to improve child social-emotional and mental health outcomes: A systematic review of economic evaluations. Sch. Ment. Health 2024, 16, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, C.; Kim, J.S.; Beretvas, T.S.; Zhang, A.; Guz, S.; Park, S.; Montgomery, K.; Chung, S.; Maynard, B.R. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions delivered by teachers in schools: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 20, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawardena, H.; Voukelatos, A.; Nair, S.; Cross, S.; Hickie, I.B. Efficacy and effectiveness of universal school-based wellbeing interventions in Australia: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelemy, D.L.; Harvey, D.K.; Waite, D.P. Meta-analysis and systematic review of teacher-delivered mental health interventions for internalizing disorders in adolescents. Ment. Health Prev. 2020, 19, 200182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, D.M.; Davies, S.R.; Thorn, J.C.; Palmer, J.C.; Caro, P.; E Hetrick, S.; Gunnell, D.; Anwer, S.; A López-López, J.; French, C.; et al. School-based interventions to prevent anxiety, depression and conduct disorder in children and young people: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Public Health Res. 2021, 6, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, M.L.; Renshaw, T.L.; Caramanico, J.; Greeson, J.M.; MacKenzie, E.; Atkinson-Diaz, Z.; Doppelt, N.; Tai, H.; Mandell, D.S.; Nuske, H.J. Mindfulness-based school interventions: A systematic review of outcome evidence quality by study design. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 1591–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, M.T. Evidence for Social and Emotional Learning in Schools. Learn. Policy Inst. 2023, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolier, L.; Haverman, M.; Westerhof, G.J.; Riper, H.; Smit, F.; Bohlmeijer, E. Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, C.; Strambler, M.J.; Naples, L.H.; Ha, C.; Kirk, M.; Wood, M.; Sehgal, K.; Zieher, A.K.; Eveleigh, A.; McCarthy, M.; et al. The state of evidence for social and emotional learning: A contemporary meta-analysis of universal school-based SEL interventions. Child Dev. 2023, 94, 1181–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenner, C.; Herrnleben-Kurz, S.; Walach, H. Mindfulness-based interventions in schools-a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuyken, W.; Ball, S.; Crane, C.; Ganguli, P.; Jones, B.; Montero-Marin, J.; Nuthall, E.; Raja, A.; Taylor, L.; Tudor, K.; et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of universal school-based mindfulness training compared with normal school provision in reducing risk of mental health problems and promoting well-being in adolescence: The MYRIAD cluster randomised controlled trial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2022, 25, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Holst, C.; Zaneva, M.; Chessell, C.; Creswell, C.; Bowes, L. Research review: Do antibullying interventions reduce internalizing symptoms? A systematic review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression exploring intervention components, moderators, and mechanisms. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 63, 1454–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.L.; Birrell, L.; Chapman, C.; Teesson, M.; Newton, N.; Allsop, S.; McBride, N.; Hides, L.; Andrews, G.; Olsen, N.; et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of a universal eHealth school-based prevention programme for depression and anxiety, and the moderating role of friendship network characteristics. Psychol. Med. 2022, 53, 5042–5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, L.; Andrews, J.L. Are mental health awareness efforts contributing to the rise in reported mental health problems? A call to test the prevalence inflation hypothesis. New Ideas Psychol. 2023, 69, 101010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, L.; Andrews, J.L.; Reardon, T.; Stringaris, A. Research recommendations for assessing potential harm from universal school-based mental health interventions. Nat. Ment. Health 2024, 2, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbukvic, I.; McKay, S.; Cooke, S.; Anderson, R.; Pilkington, V.; McGillivray, L.; Bailey, A.; Purcell, R.; Tye, M. Evidence for targeted and universal secondary school-based programs for anxiety and depression: An overview of systematic reviews. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2023, 9, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjermestad, K.W.; Wergeland, G.J.; Rogde, A.; Bjaastad, J.F.; Heiervang, E.; Haugland, B.S.M. School-based targeted prevention compared to specialist mental health treatment for youth anxiety. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 25, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K.K.Y.; Anderson, J.K.; Burn, A. Review: School-based interventions to improve mental health literacy and reduce mental health stigma — A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 28, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of health care interventions: A theoretical framework and proposed research agenda. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Patterson, M.; Wood, S.; Booth, A.; Rick, J.; Balain, S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement. Sci. 2007, 2, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Klesges, L.M.; Dzewaltowski, D.A.; Estabrooks, P.A.; Vogt, T.M. Evaluating the impact of health promotion programs: Using the RE-AIM framework to form summary measures for decision making involving complex issues. Health Educ. Res. 2006, 21, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, R.P.; Evans, M.H.; Joshi, P. Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: A how-to guide. Health Promot. Pract. 2005, 6, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fàbregues, S.; Mumbardó-Adam, C.; Escalante-Barrios, E.L.; Hong, Q.N.; Edelstein, D.; Vanderboll, K.; Fetters, M.D. Mixed methods intervention studies in children and adolescents with emotional and behavioral disorders: A methodological review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 126, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.B.; Finley, E.P. Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 280, 112516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S.I.; Kishida, K.; Oka, T.; Saito, A.; Shimotsu, S.; Watanabe, N.; Sasamori, H.; Kamio, Y. Developing the universal unified prevention program for diverse disorders for school-aged children. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2019, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, T.; Ishikawa, S.I.; Saito, A.; Maruo, K.; Stickley, A.; Watanabe, N.; Sasamori, H.; Shioiri, T.; Kamio, Y. Changes in self-efficacy in Japanese school-age children with and without high autistic traits after the Universal Unified Prevention Program: A single-group pilot study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2021, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishida, K.; Hida, N.; Ishikawa, S.I. Evaluating the effectiveness of a transdiagnostic universal prevention program for both internalizing and externalizing problems in children: Two feasibility studies. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.; Woolfson, L.M.; Durkin, K. Effects on coping skills and anxiety of a universal school-based mental health intervention delivered in Scottish primary schools. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2013, 35, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Houghton, S.; Forrest, K.; McCarthy, M.; Sanders-O’cOnnor, E. Who benefits most? Predicting the effectiveness of a social and emotional learning intervention according to children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2020, 41, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourander, A.; Ishikawa, S.; Ståhlberg, T.; Kishida, K.; Mori, Y.; Matsubara, K.; Zhang, X.; Hida, N.; Korpilahti-Leino, T.; Ristkari, T.; et al. Cultural adaptation, content, and protocol of a feasibility study of school-based “Let’s learn about emotions” intervention for Finnish primary school children. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1334282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attkisson, C.C.; Greenfield, T.K. The client satisfaction questionnaire-8 and the service satisfaction questionnaire-30. In Outcome Assessment in Clinicalpractice; Sederer, L.L., Dickey, B., Eds.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, Maryland, 1996; pp. 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muris, P.; Meesters, C.; Eijkelenboom, A.; Vincken, M. The self-report version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire: Its psychometric properties in 8- to 13-year-old non-clinical children. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 43, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.L.; Otten, R.; Engels, R.C.; Vermulst, A.A.; Janssens, J.M.A.M. Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for 4- to 12-year-olds: A review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 13, 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, A.M.; Kaukonen, P.; Salmelin, R.; Joukamaa, M.; Tamminen, T. Reliability of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire among finnish 4–9-year-old children. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2012, 66, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankaanpää, R.; Töttö, P.; Punamäki, R.-L.; Peltonen, K. Is it time to revise the SDQ? The psychometric evaluation of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Psychol. Assess. 2023, 35, 1069–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskelainen, M.; Sourander, A.; Kaljonen, A. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire among Finnish school-aged children and adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2000, 9, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, L.; Närhi, V.; Savolainen, H.; Schwab, S. Classroom behavioural climate in inclusive education-a study on secondary students’ perceptions. J. Res. Spéc. Educ. Needs 2021, 21, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Närhi, V.; Kiiski, T.; Savolainen, H. Reducing disruptive behaviours and improving classroom behavioural climate with class-wide positive behaviour support in middle schools. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 43, 1186–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI); Multi-Health Systems: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lempinen, L.; Junttila, N.; Sourander, A. Loneliness and friendships among eight-year-old children: Time-trends over a 24-year period. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourander, A.; Klomek, A.B.; Ikonen, M.; Lindroos, J.; Luntamo, T.; Koskelainen, M.; Ristkari, T.; Helenius, H. Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. 2021. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide, 1st ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–376. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, A.L.; Rhoades, K.A.; Eddy, J.M.; Slep, A.M.S.; Kim, T.E.; Currie, C. What do parents know about social-emotional learning in their children’s schools? Gaps and opportunities for strengthening intervention impact. Soc. Emot. Learn. Res. Pract. Policy 2024, 4, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklad, M.; Diekstra, R.; DE Ritter, M.; BEN, J.; Gravesteijn, C. Effectiveness of school-based universal social, emotional, and behavioral programs: Do they enhance students’ development in the area of skill, behavior, and adjustment? Psychol. Sch. 2012, 49, 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torok, M.; Rasmussen, V.; Wong, Q.; Werner-Seidler, A.; O’DEa, B.; Toumbourou, J.; Calear, A. Examining the impact of the good behaviour game on emotional and behavioural problems in primary school children: A case for integrating well-being strategies into education. Aust. J. Educ. 2019, 63, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, M.; Robbins, J.M.; Tesfaye, M. Parents’ perception of child and adolescent mental health problems and their choice of treatment option in southwest Ethiopia. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2015, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, K.; Williams, C. Universal, school-based interventions to promote mental and emotional well-being: What is being done in the UK and does it work? A systematic review. BMJ. Open 2018, 8, e022560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, K.M.; Platt, J.M. Annual Research Review: Sex, gender, and internalizing conditions among adolescents in the 21st century-trends, causes, consequences. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 65, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiviruusu, O.; Ranta, K.; Lindgren, M.; Haravuori, H.; Silén, Y.; Therman, S.; Lehtonen, J.; Sares-Jäske, L.; Aalto-Setälä, T.; Marttunen, M.; et al. Mental health after the COVID-19 pandemic among Finnish youth: A repeated, cross-sectional, population-based study. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Categories | Baseline (T0) | Post-Intervention (T1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Students | (n = 233) | (n = 209) | |

| Gender | Male | 116 (49.8%) | 108 (51.7%) |

| Female | 106 (45.5%) | 85 (40.7%) | |

| Other | 7 (3.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Do not want to tell | 4 (1.7%) | 10 (4.8%) | |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 5 (2.4%) | |

| Mother tongue | Finnish only | 210 (90.1%) | 179 (85.6%) |

| Swedish only | 3 (1.3%) | 6 (2.9%) | |

| Finnish and Swedish | 7 (3.0%) | 3 (1.4%) | |

| Finnish and other | 2 (0.9%) | 3 (1.4%) | |

| Others | 10 (4.3%) | 8 (3.8%) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.4%) | 10 (4.8%) | |

| Teachers | (n = 20) | (n = 17) | |

| Gender | Male | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Female | 20 (100%) | 20 (100%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Do not want to tell | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Age (Mean ± SD 1) | - | 46.6 (11.2) | 47.4 (12.1) |

| Parents | (n = 256) | (n = 154) | |

| Relationship to student | Mother | 172 (67.2%) | 127 (82.5%) |

| Father | 31 (12.1%) | 17 (11.0%) | |

| Both parents | 40 (15.6%) | 7 (4.5%) | |

| Other | 4 (1.6%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| Missing | 9 (3.5%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Questions | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students (N = 209) | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | |

| Content was easy to understand | 142 (69.3) | 52 (25.4) | 11 (5.4) | |

| I understood how to use tools | 126 (61.2) | 69 (33.5) | 11 (5.3) | |

| I was satisfied with the program | 115 (55.6) | 78 (37.7) | 14 (6.8) | |

| Program was good | 112 (54.1) | 82 (39.6) | 13 (6.3) | |

| I liked the classes | 103 (50.0) | 84 (40.8) | 19 (9.2) | |

| Program made me feel better | 57 (27.7) | 109 (52.9) | 40 (19.4) | |

| Program helped me | 55 (26.6) | 118 (57.0) | 34 (16.4) | |

| I will use tools in or outside of school | 54 (26.3) | 82 (40.0) | 69 (33.7) | |

| I have used tools in or outside of school | 39 (19.0) | 77 (37.6) | 89 (43.4) | |

| Parents (n = 154) | Definitely true | Somewhat true | Not true at all | Cannot say |

| I was satisfied with the amount of information received about the program | 72 (48.3) | 57 (38.3) | 6 (4.0) | 14 (9.4) |

| Program seemed good | 94 (63.1) | 32 (21.5) | 0 (0) | 23 (15.4) |

| I would recommend the program for others | 91 (61.1) | 27 (18.1) | 1 (0.7) | 30 (20.1) |

| Homework was easy to understand for the child | 68 (45.6) | 43 (28.9) | 1 (0.7) | 37 (24.8) |

| Content of the program was easy to understand for the child | 70 (47.0) | 40 (26.8) | 2 (1.3) | 37 (24.8) |

| Teachers (n = 17) | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | |

| Program | ||||

| Teacher’s material was easy to understand | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| It was easy to follow structure while teaching | 16 (94.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Students were able to easily understand the material | 15 (93.8) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Students liked the program | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0) | |

| I got help from the program | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0) | |

| I have made use of program’s content in my work | 15 (88.2) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | |

| I will make use of program’s content in my work | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Learning the teaching material took feasible amount of time | 14 (82.4) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (5.9) | |

| I would recommend the program to others | 13 (76.5) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (11.8) | |

| My school supports program’s content | 12 (70.6) | 5 (29.4) | 0 (0) | |

| I liked the program | 12 (70.6) | 4 (23.5) | 1 (5.9) | |

| My school supports using the program | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | 0 (0) | |

| I was satisfied with the program | 11 (64.7) | 4 (23.5) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Training workshop | ||||

| Training gave good background for the program | 17 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| I was satisfied with the amount of training | 14 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| I was satisfied with the quality of training | 5 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Training gave good basis for teaching the program | 15 (88.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Written teacher’s material was comprehensive | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0) | |

| It was easy to contact the research team | 12 (85.7) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Research team gave satisfactory answers | 12 (80.0) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.6) | |

| Written teacher’s material was easy to use | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Introduction videos were useful | 5 (35.7) | 3 (21.4) | 6 (42.9) | |

| Online meetings during the course aided my work | 0 (0) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) |

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Usability and clarity | Program structure, content, and visual design Role of parents |

| Perceived usefulness | Need for improved socio-emotional skills Improvements in everyday life |

| Contextual fit | Suitability for the age group Fit to educational practices |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mori, Y.; Ståhlberg, T.; Zhang, X.; Mishina, K.; Herkama, S.; Korpilahti-Leino, T.; Ristkari, T.; Kanasuo, M.; Siirtola, S.; Närhi, V.; et al. Let’s Learn About Emotions Program: Acceptability, Fidelity, and Students’ Mental Well-Being Outcomes for Finnish Primary School Children. Children 2025, 12, 1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091251

Mori Y, Ståhlberg T, Zhang X, Mishina K, Herkama S, Korpilahti-Leino T, Ristkari T, Kanasuo M, Siirtola S, Närhi V, et al. Let’s Learn About Emotions Program: Acceptability, Fidelity, and Students’ Mental Well-Being Outcomes for Finnish Primary School Children. Children. 2025; 12(9):1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091251

Chicago/Turabian StyleMori, Yuko, Tiia Ståhlberg, Xiao Zhang, Kaisa Mishina, Sanna Herkama, Tarja Korpilahti-Leino, Terja Ristkari, Meeri Kanasuo, Saara Siirtola, Vesa Närhi, and et al. 2025. "Let’s Learn About Emotions Program: Acceptability, Fidelity, and Students’ Mental Well-Being Outcomes for Finnish Primary School Children" Children 12, no. 9: 1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091251

APA StyleMori, Y., Ståhlberg, T., Zhang, X., Mishina, K., Herkama, S., Korpilahti-Leino, T., Ristkari, T., Kanasuo, M., Siirtola, S., Närhi, V., Savolainen, H., Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S., Torii, S., Matsubara, K., Kishida, K., Hida, N., Ishikawa, S.-i., & Sourander, A. (2025). Let’s Learn About Emotions Program: Acceptability, Fidelity, and Students’ Mental Well-Being Outcomes for Finnish Primary School Children. Children, 12(9), 1251. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091251