Mediational Patterns of Parenting Styles Between Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome Difficulties and Youth Psychopathology

Abstract

Highlights

- Negative parenting practices (poor monitoring, inconsistent discipline, corporal punishment) partially mediate the relationship between Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome (CDS) symptoms and youth anxiety, depression, and oppositional–defiant symptoms.

- Positive parenting practices, although beneficial, did not play a significant mediating role in these associations.

- Children’s CDS-related difficulties may lead parents to adopt negative parenting behaviors, which in turn exacerbate psychopathological symptoms in their offspring.

- Clinical and preventive interventions should prioritize reducing negative parenting practices, alongside promoting positive ones, to mitigate the impact of CDS on youth mental health.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Main Analyses: Mediation Model

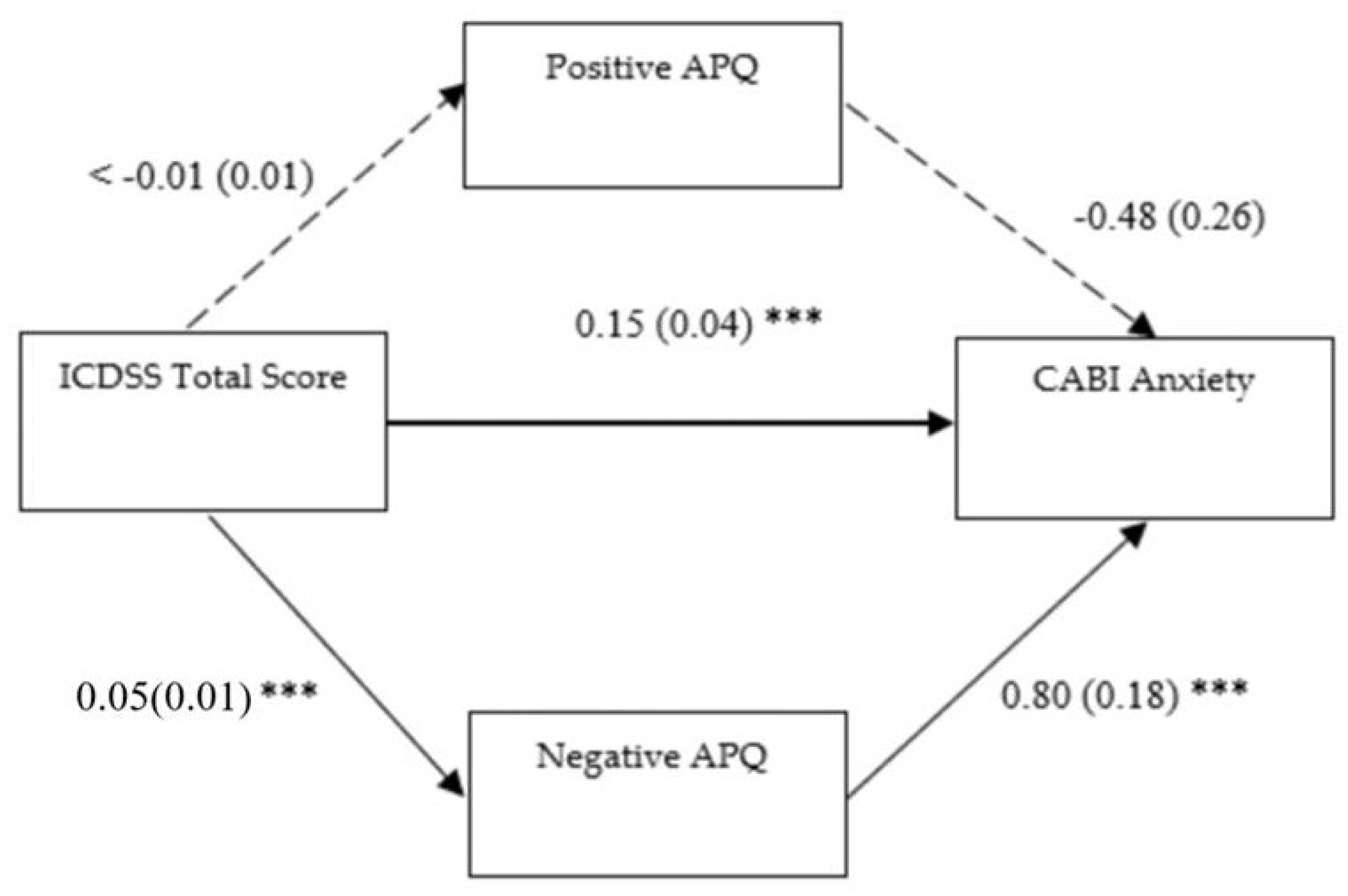

3.2.1. First Mediation Model

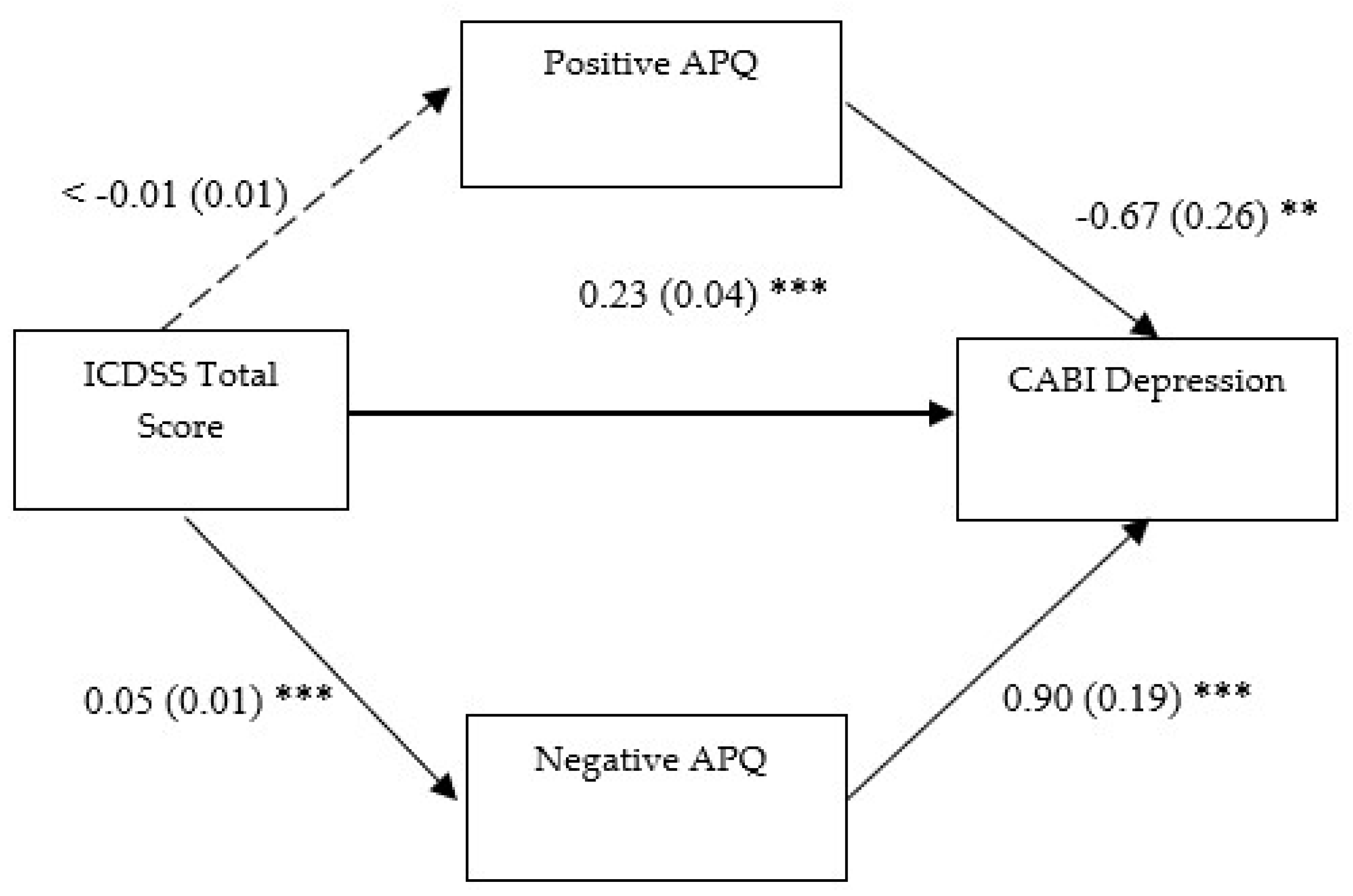

3.2.2. Second Mediation Model

3.2.3. Third Mediation Model

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDS | Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome |

| APQ | Alabama Parenting Questionnaire |

| ICDSS | Italian Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome Scale |

| CABI | Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory |

References

- Barkley, R.A. Distinguishing sluggish cognitive tempo from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2012, 121, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Willcutt, E.G.; Leopold, D.R.; Fredrick, J.W.; Smith, Z.R.; Jacobson, L.A.; Burns, G.L.; Mayes, S.D.; Waschbusch, D.A.; Froehlich, T.E.; et al. Report of a Work Group on Sluggish Cognitive Tempo: Key Research Directions and a Consensus Change in Terminology to Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 62, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, L.A.; Murphy-Bowman, S.C.; Pritchard, A.E.; Tart-Zelvin, A.; Zabel, T.A.; Mahone, E.M. Factor Structure of a Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale in Clinically-Referred Children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2012, 40, 1327–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, A.M.; Waschbusch, D.A.; Klein, R.M.; Corkum, P.; Eskes, G. Developing a measure of sluggish cognitive tempo for children: Content validity, factor structure, and reliability. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Luebbe, A.M.; Fite, P.J.; Stoppelbein, L.; Greening, L. Sluggish Cognitive Tempo in Psychiatrically Hospitalized Children: Factor Structure and Relations to Internalizing Symptoms, Social Problems, and Observed Behavioral Dysregulation. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langberg, J.M.; Becker, S.P.; Dvorsky, M.R.; Luebbe, A.M. Are sluggish cognitive tempo and daytime sleepiness distinct constructs? Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Burns, G.L.; Snell, J.; McBurnett, K. Validity of the Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Symptom Dimension in Children: Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and ADHD-Inattention as Distinct Symptom Dimensions. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Z.R.; Eadeh, H.-M.; Breaux, R.P.; Langberg, J.M. Sleepy, sluggish, worried, or down? The distinction between self-reported sluggish cognitive tempo, daytime sleepiness, and internalizing symptoms in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 31, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcutt, E.G.; Chhabildas, N.; Kinnear, M.; DeFries, J.C.; Olson, R.K.; Leopold, D.R.; Keenan, J.M.; Pennington, B.F. The Internal and External Validity of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and its Relation with DSM–IV ADHD. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Leopold, D.R.; Burns, G.L.; Jarrett, M.A.; Langberg, J.M.; Marshall, S.A.; McBurnett, K.; Waschbusch, D.A.; Willcutt, E.G. The Internal, External, and Diagnostic Validity of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo: A Meta-Analysis and Critical Review. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.P.; Marshall, S.A.; McBurnett, K. Sluggish Cognitive Tempo in Abnormal Child Psychology: An Historical Overview and Introduction to the Special Section. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A. Distinguishing Sluggish Cognitive Tempo From ADHD in Children and Adolescents: Executive Functioning, Impairment, and Comorbidity. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2013, 42, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyurt, G.; Tanıgör, E.K.; Buran, B.Ş.; Öztürk, Y.; Tufan, A.E.; Akay, A. Similarities and differences of neuropsychological functions, metacognitive abilities and resilience in Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome (CDS) and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Appl. Neuropsychol. Child. 2024, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxbe, C.; Barkley, R.A. The Second Attention Disorder? Sluggish Cognitive Tempo vs. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Update for Clinicians. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2014, 20, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.A.; Evans, S.W.; Eiraldi, R.B.; Becker, S.P.; Power, T.J. Social and Academic Impairment in Youth with ADHD, Predominately Inattentive Type and Sluggish Cognitive Tempo. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Z.R.; Langberg, J.M. Do sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms improve with school-based ADHD interventions? Outcomes and predictors of change. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P. Sluggish cognitive tempo and peer functioning in school-aged children: A six-month longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 217, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.P.; Garner, A.A.; Tamm, L.; Antonini, T.N.; Epstein, J.N. Honing in on the Social Difficulties Associated with Sluggish Cognitive Tempo in Children: Withdrawal, Peer Ignoring, and Low Engagement. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 48, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, N.M.; King, S.L.; Hilton, D.C.; Rondon, A.T.; Jarrett, M.A. Social Functioning in Youth with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Sluggish Cognitive Tempo. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2019, 92, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, T.W.K.; Lai, C.Y.Y.; Chan, J.Y.C.; Ng, S.S.M.; Chan, C.C.H. Examining the Role of Attention Deficits in the Social Problems and Withdrawn Behavior of Children with Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Symptoms. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 585589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creque, C.A.; Willcutt, E.G. Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and Neuropsychological Functioning. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, A.J.; Luebbe, A.M.; Becker, S.P. Sluggish Cognitive Tempo is Associated with Poorer Study Skills, More Executive Functioning Deficits, and Greater Impairment in College Students: Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and College Student Adjustment. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 73, 1091–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamm, L.; Brenner, S.B.; Bamberger, M.E.; Becker, S.P. Are sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms associated with executive functioning in preschoolers? Child Neuropsychol. 2018, 24, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, A.J.; Becker, S.P.; Luebbe, A.M. Does Emotion Dysregulation Mediate the Association Between Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and College Students’ Social Impairment? J. Atten. Disord. 2016, 20, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, L.A.; Geist, M.; Mahone, E.M. Sluggish Cognitive Tempo, Processing Speed, and Internalizing Symptoms: The Moderating Effect of Age. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 46, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Burns, G.L.; Leopold, D.R.; Olson, R.K.; Willcutt, E.G. Differential impact of trait sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD inattention in early childhood on adolescent functioning. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrick, J.W.; Becker, S.P. Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome (Sluggish Cognitive Tempo) and Social Withdrawal: Advancing a Conceptual Model to Guide Future Research. J. Atten. Disord. 2023, 27, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, S.; Amico, C.; De Giuli, G.; Giani, L.; Fagnani, C.; Medda, E.; Scaini, S. Exploring the comorbidity between internalizing/externalizing dimensions and cognitive disengagement syndrome through twin studies: A narrative review. J. Transl. Genet. Genom. 2024, 8, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrick, J.W.; Kofler, M.J.; Jarrett, M.A.; Burns, G.L.; Luebbe, A.M.; Garner, A.A.; Harmon, S.L.; Becker, S.P. Sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD symptoms in relation to task-unrelated thought: Examining unique links with mind-wandering and rumination. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 123, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Webb, K.L.; Dvorsky, M.R. Initial Examination of the Bidirectional Associations between Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and Internalizing Symptoms in Children. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2021, 50, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.P.; Barkley, R.A. Field of daydreams? Integrating mind wandering in the study of sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD. JCPP Adv. 2021, 1, e12002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoff, K.; Irving, Z.C.; Fox, K.C.R.; Spreng, R.N.; Andrews-Hanna, J.R. Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: A dynamic framework. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uytun, M.C.; Yurumez, E.; Babayigit, T.M.; Efendi, G.Y.; Kilic, B.G.; Oztop, D.B. Sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms cooccurring with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, G.L.; Servera, M.; Bernad, M.D.M.; Carrillo, J.M.; Cardo, E. Distinctions Between Sluggish Cognitive Tempo, ADHD-IN, and Depression Symptom Dimensions in Spanish First-Grade Children. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2013, 42, 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, C.A.; Willcutt, E.G.; Rhee, S.H.; Pennington, B.F. The Relation Between Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and DSM-IV ADHD. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2004, 32, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servera, M.; Bernad, M.D.M.; Carrillo, J.M.; Collado, S.; Burns, G.L. Longitudinal Correlates of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and ADHD-Inattention Symptom Dimensions with Spanish Children. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2016, 45, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevincok, D.; Ozbay, H.C.; Ozbek, M.M.; Tunagur, M.T.; Aksu, H. ADHD symptoms in relation to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children: The mediating role of sluggish cognitive tempo. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2020, 74, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, S. Examination of symptoms related to cognitive disengagement syndrome in a clinical cohort of school-aged children. Dusunen Adam J. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 2023, 36, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaini, S.; Medda, E.; Battaglia, M.; De Giuli, G.; Stazi, M.A.; D’iPpolito, C.; Fagnani, C. A Twin Study of the Relationships between Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome and Anxiety Phenotypes in Childhood and Adolescence. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2023, 51, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, A.; Dias, P.; Soares, I. Risk Factors for Internalizing and Externalizing Problems in the Preschool Years: Systematic Literature Review Based on the Child Behavior Checklist 1½–5. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2941–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, E.C.; Aggen, S.H.; Gardner, C.; Kendler, K.S. Differential parenting and risk for psychopathology: A monozygotic twin difference approach. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullineaux, P.Y.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Petrill, S.A.; Thompson, L.A. Parenting and child behaviour problems: A longitudinal analysis of non-shared environment. Infant Child Dev. 2009, 18, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikstat, A.; Riemann, R. Differences in Parenting Behavior are Systematic Sources of the Non-shared Environment for Internalizing and Externalizing Problem Behavior. Behav. Genet. 2023, 53, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Hastings, P.D.; Lagacé-Séguin, D.G.; Moulton, C.E. Authoritative and Authoritarian Mothers’ Parenting Goals, Attributions, and Emotions Across Different Childrearing Contexts. Parenting 2002, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorostiaga, A.; Aliri, J.; Balluerka, N. Lameirinhas. Parenting Styles and Internalizing Symptoms in Adolescence: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 873–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Silva, A.; Lago-Urbano, R.; Sanchez-Garcia, M. Family Impact and Parenting Styles in Families of Children with ADHD. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 2810–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, A.M.; French, B.F.; Dumas, J.E.; Moreland, A.D.; Prinz, R. Bidirectional Effects of Parenting Quality and Child Externalizing Behavior in Predominantly Single Parent, Under-Resourced African American Families. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, N.M.; McBurnett, K.; Pfiffner, L.J. Child ADHD Severity and Positive and Negative Parenting as Predictors of Child Social Functioning: Evaluation of Three Theoretical Models. J. Atten. Disord. 2011, 15, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, G.; Sheerin, D.; Carr, A.; Dooley, B.; Barton, V.; Marshall, D.; Mulligan, A.; Lawlor, M.; Belton, M.; Doyle, M. Family factors associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and emotional disorders in children. J. Fam. Ther. 2005, 27, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, D.P.; Harrison, C.A. Parenting Practices of Mothers of Children with ADHD: The Role of Maternal and Child Factors. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2006, 11, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, A.E.; Canu, W.H.; Lefler, E.K.; Hartung, C.M. Maternal Parenting Style and Internalizing and ADHD Symptoms in College Students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, L.; Ingrassia, M. Misurare le pratiche genitoriali: L’Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ). Disturbi Attenzione Iperattività 2012, 7, 121–146. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, A.; Servera, M.; Garcia-Banda, G.; Del Giudice, E. Factor Analysis of the Italian Version of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire in a Community Sample. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, G.L.; Lee, S.; Servera, M.; McBurnett, K.; Becker, S.P. Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory—Parent Version 1.0; Authors: Pullman, WA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cianchetti, C.; Pittau, A.; Carta, V.; Campus, G.; Littarru, R.; Ledda, M.G.; Zuddas, A.; Fancello, G.S. Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI): A New Instrument for Epidemiological Studies and Pre-Clinical Evaluation. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2013, 9, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2013. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=1787696 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. xvii, 507. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, B.D.; Wood, J.J.; Weisz, J.R. Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, Y. Establishing specific links between parenting styles and the s-anxieties in children: Separation, social, and school. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, B.D.; Weisz, J.R.; Wood, J.J. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 986–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.B.H.; Pilkington, P.D.; Ryan, S.M.; Jorm, A.F. Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 156, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciver, L.; O’Connor, L.; Warrington, J.; McCann, A. The association between paternal depression and adolescent internalising problems: A test of parenting style as a mediating pathway. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 21213–21226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Gardner, L.; Hyde, L. What are the associations between parenting, callous-unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 42, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.D.; Pardini, D.A.; Loeber, R. Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2008, 36, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.L.; Wessels, I.M.; Lachman, J.M.; Hutchings, J.; Cluver, L.D.; Kassanjee, R.; Nhapi, R.; Little, F.; Gardner, F. Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children: A randomized controlled trial of a parenting program in South Africa to prevent harsh parenting and child conduct problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive APQ | −0.29 *** | −0.15 ** | −0.13 * | −0.20 *** | −0.19 *** |

| 2. Negative APQ | - | 0.32 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.47 *** |

| 3. ICDSS Tot | - | 0.46 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.54 *** | |

| 4. CABI Anxiety | - | 0.63 *** | 0.49 *** | ||

| 5. CABI Depression | - | 0.55 *** | |||

| 6. CABI ODD | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giani, L.; De Francesco, S.; Amico, C.; De Giuli, G.; Caputi, M.; Scaini, S. Mediational Patterns of Parenting Styles Between Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome Difficulties and Youth Psychopathology. Children 2025, 12, 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091134

Giani L, De Francesco S, Amico C, De Giuli G, Caputi M, Scaini S. Mediational Patterns of Parenting Styles Between Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome Difficulties and Youth Psychopathology. Children. 2025; 12(9):1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091134

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiani, Ludovica, Stefano De Francesco, Cecilia Amico, Gaia De Giuli, Marcella Caputi, and Simona Scaini. 2025. "Mediational Patterns of Parenting Styles Between Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome Difficulties and Youth Psychopathology" Children 12, no. 9: 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091134

APA StyleGiani, L., De Francesco, S., Amico, C., De Giuli, G., Caputi, M., & Scaini, S. (2025). Mediational Patterns of Parenting Styles Between Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome Difficulties and Youth Psychopathology. Children, 12(9), 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091134