Evaluation of the Acceptability and Feasibility of the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance-Revised (SACS-R) Tool for Early Identification of Autism in Preterm Infants: The Identify and Act Study

Abstract

Highlights

- Routine use of the SACS-R tool in a high-risk preterm infant follow-up clinic was found to be both feasible and acceptable to caregivers and clinicians, with strong support for its integration into standard practice.

- The study identified 8.5% of screened children as having a high likelihood of autism—consistent with existing prevalence data—and highlighted delays in pointing and imitation as key early markers in this population.

- The successful implementation of the SACS-R tool in a high-risk preterm clinic suggests it can be effectively integrated into routine developmental surveillance, enabling earlier identification of autism in vulnerable populations.

- Early detection facilitates timely referral to intervention services, potentially improving long-term developmental outcomes for preterm infants.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Objectives

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.2.1. Infants

2.2.2. Clinicians

2.3. Tools Used

- Demographic questionnaire: Completed by clinicians, and included patient gestation at birth (GA), birth weight (BW), significant complications during NICU stay, ethnicity, languages spoken at home, primary language, parental education, family history of autism, maternal comorbidities during antenatal period and reported developmental concerns.

- SACS-R 12-month checklist: The SACS-R evaluates early social-communication behaviors across five key items (eye contact, pointing, gestures, imitation, and response to name) and five non-key items (social smiling, babble, following a point, early word use, comprehension). Each behavior is coded as ‘typical’ (eye contact: child makes regular and consistent eye contact with examiner and caregiver across different settings, pointing: child points to show something that is out of reach and turns to look at you, gestures: child uses gestures such as waving or clapping, imitation: child copies examiner’s or caregiver’s actions, response to name: child consistently responds to his/her name when called) or atypical; ≥3 atypical key items classify a child as ‘high likelihood (HL)’ for autism, prompting referral to early intervention if available (Appendix A).

- Caregiver acceptability and feasibility questionnaires: Acceptability (8 items) and feasibility (11 items) were rated on a 5-point Likert scale with open-ended questions regarding tool clarity, relevance, mode of administration, and emotional impact (Appendix A).

- Clinician acceptability and feasibility questionnaires: Administered post-study via REDCap, using similar 5-point scales and open-ended questions regarding ease of use, practicality, and integration into clinical workflow (Appendix A).

2.4. Procedures and EI Referral

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

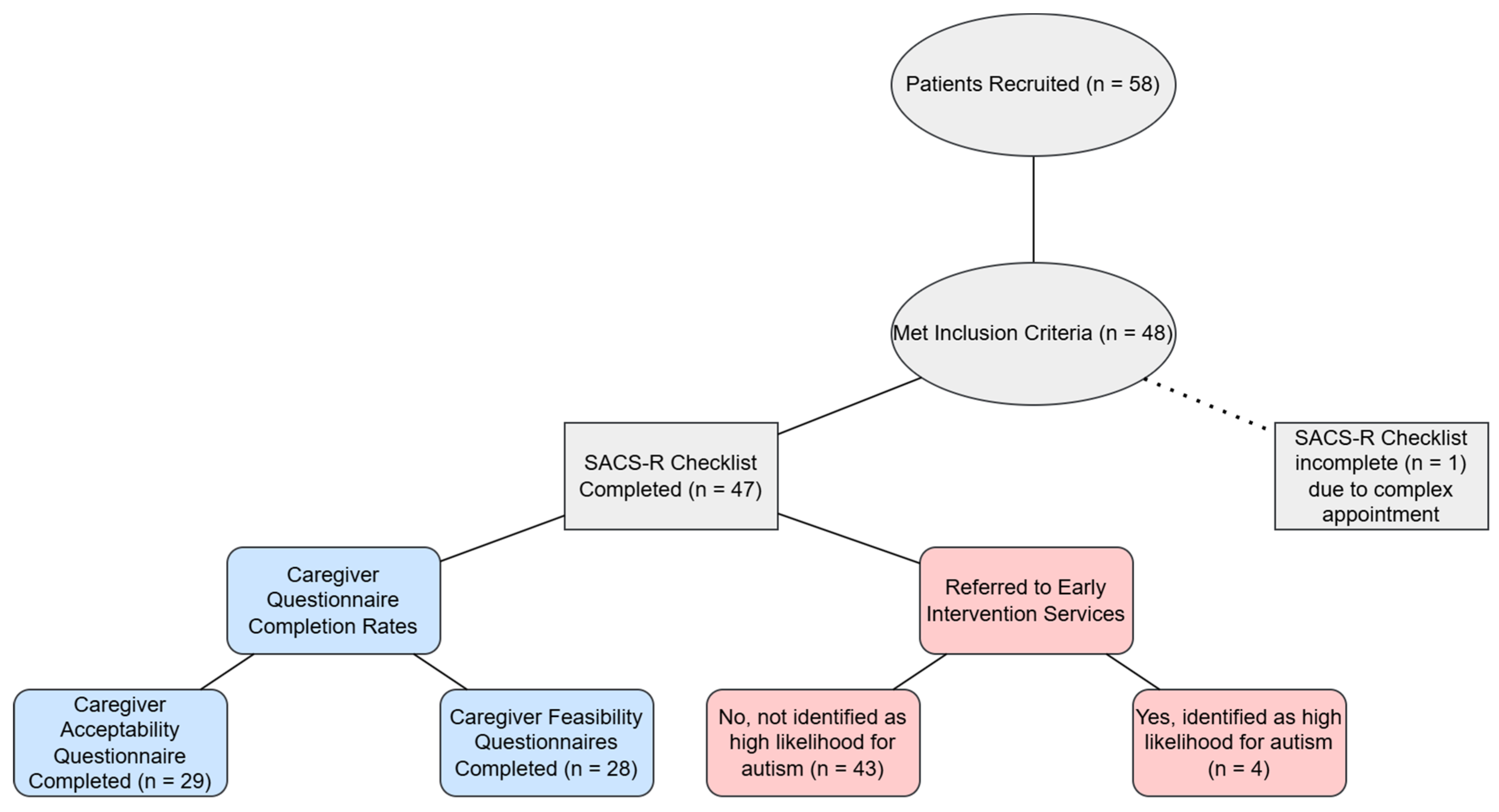

3.2. Screening Using the 12 Month-SACS-R Checklist

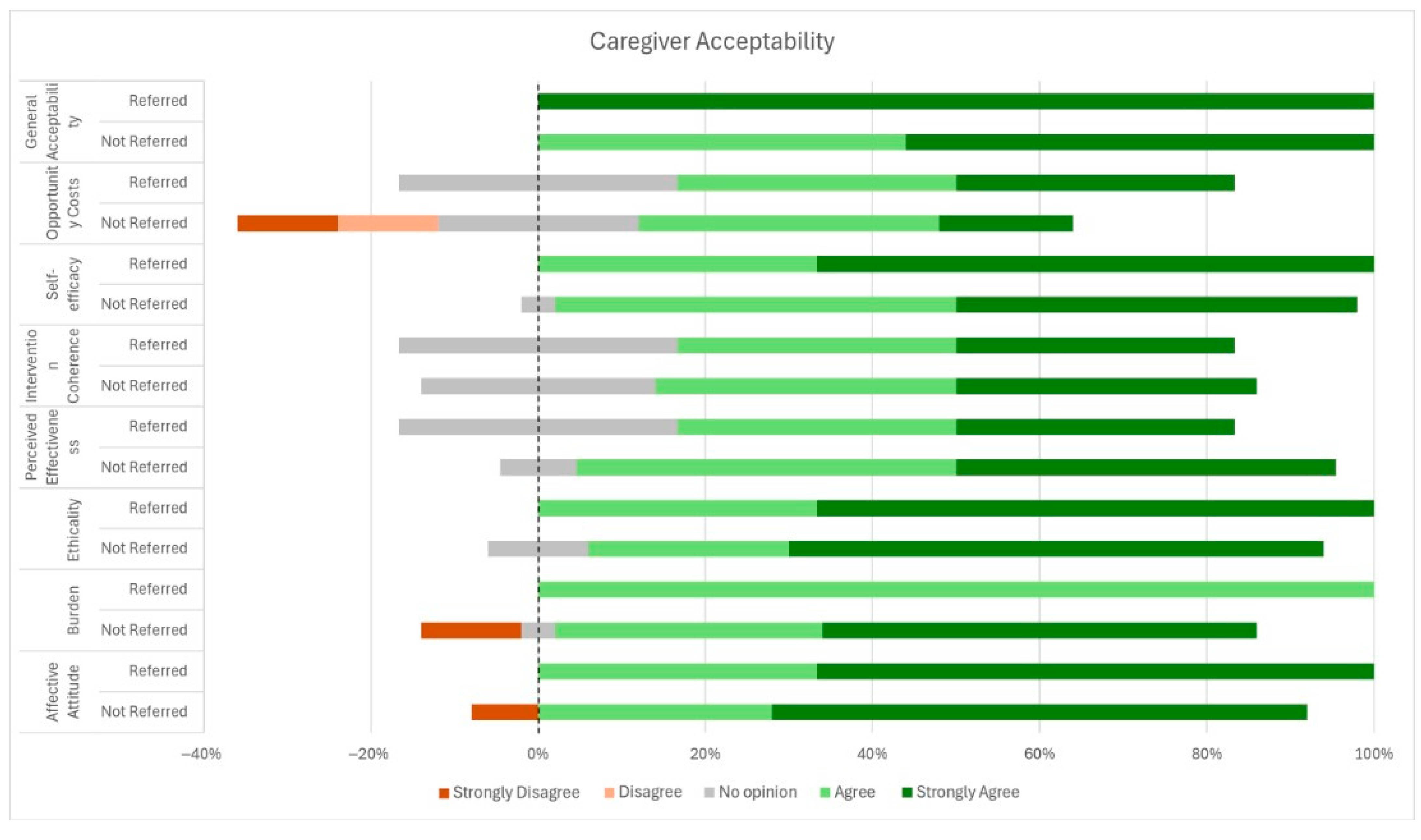

3.3. Caregiver Acceptability and Feasibility

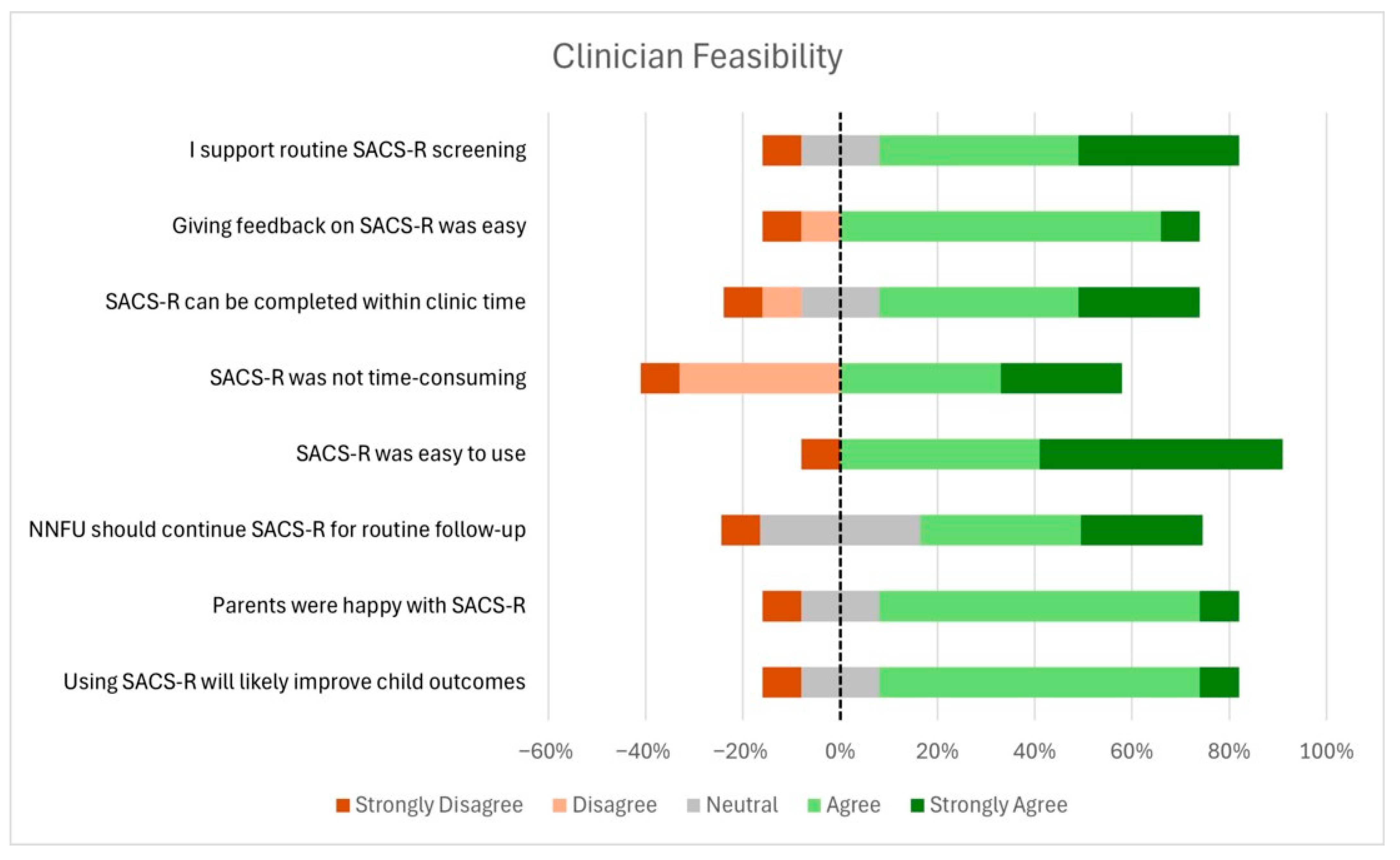

3.4. Clinician Characteristics

3.5. Clinician Acceptability and Feasibility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- May, T.; Williams, K. Brief Report: Gender and Age of Diagnosis Time Trends in Children with Autism Using Australian Medicare Data. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 4056–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Autism in Australia, 2022 [Internet]; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2023. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/autism-australia-2022#autism-prevalence (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Crump, C.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Preterm or Early Term Birth and Risk of Autism. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020032300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.Q.; Li, H.B.; Zhai, D.S.; Yang, L.Q. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder diagnosis by birth weight, gestational age, and size for gestational age: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 2035–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, E.C.; Sheinkopf, S.J. Autism and Preterm Birth: Clarifying Risk and Exploring Mechanisms. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021051978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokobza, C.; Van Steenwinckel, J.; Mani, S.; Mezger, V.; Fleiss, B.; Gressens, P. Neuroinflammation in preterm babies and autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 85, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bent, C.A.; Dissanayake, C.; Barbaro, J. Mapping the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders in children aged under 7 years in Australia, 2010–2012. Med. J. Aust. 2015, 202, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, J.; Lee, T.J.; Bullot, A. Sociodemographic and Clinical Profile of 915 Autistic Preschoolers Engaged in Intensive Early Intervention in Australia. J. Autism. Dev. Disord 2024. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, G.; Rieder, A.D.; Johnson, M.H. Prediction of autism in infants: Progress and challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.Y.; Fatemi, A.; Johnston, M.V. Cerebral plasticity: Windows of opportunity in the developing brain. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2017, 21, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spittle, A.; Orton, J.; Anderson, P.J.; Boyd, R.; Doyle, L.W. Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 2, CD005495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J.J.; Piven, J. Predicting autism in infancy. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2021, 60, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieckowski, A.T.; Williams, L.N.; Rando, J.; Lyall, K.; Robins, D.L. Sensitivity and specificity of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (original and revised): A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrocchi, S.; Levante, A.; Lecciso, F. Systematic Review of Level 1 and Level 2 Screening Tools for Autism Spectrum Disorders in Toddlers. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturner, R.; Howard, B.; Bergmann, P.; Attar, S.; Stewart-Artz, L.; Bet, K.; Allison, C.; Baron-Cohen, S. Autism screening at 18 months of age: A comparison of the Q-CHAT-10 and M-CHAT screeners. Mol. Autism. 2022, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, J.; Sadka, N.; Gilbert, M.; Beattie, E.; Li, X.; Ridgway, L.; Lawson, L.P.; Dissanayake, C. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance-Revised with Preschool Tool for Early Autism Detection in Very Young Children. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2146415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehouse, A.J.O.; Varcin, K.J.; Pillar, S.; Billingham, W.; Alvares, G.A.; Barbaro, J.; Bent, C.A.; Blenkley, D.; Boutrus, M.; Chee, A.; et al. Effect of Preemptive Intervention on Developmental Outcomes Among Infants Showing Early Signs of Autism: A Randomized Clinical Trial of Outcomes to Diagnosis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, e213298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, J.; Jellett, R.; Yaari, M.; Gilbert, M.; Barbaro, J. A Comparison of Children Born Preterm and Full-Term on the Autism Spectrum in a Prospective Community Sample. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 597505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomero-Sierra, B.; Sánchez-Gómez, V.; Magán-Maganto, M.; Bejarano-Martín, Á.; Ruiz-Ayúcar, I.; de Vena-Díez, V.B.; Mannarino, G.V.; Díez-Villoria, E.; Canal-Bedia, R. Early social communication and language development in moderate-to-late preterm infants: A longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1556416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athalye-Jape, G.; Abdul Aziz, S.; Sherrard, S.; Saminathan, S.; Wu Karissa Sharp, M. Use of the Social Attention Communication-Revised (SACS-R) checklist for clinician suspected autism referrals in a preterm high-risk follow-up clinic in Western Australia. PSANZ 2025 poster. JPCH 2025, 61, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Deming, W.E. Out of the Crisis; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.; Hollis, C.; Kochhar, P.; Hennessy, E.; Wolke, D.; Marlow, N. Autism spectrum disorders in extremely preterm children. J. Pediatr. 2010, 156, 525–531.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.M.; O’Shea, T.M.; Allred, E.N.; Heeren, T.; Hirtz, D.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Kuban, K.C.K. Prevalence and associated features of autism spectrum disorder in extremely low gestational age newborns at age 10 years. Autism. Res. 2017, 10, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Rao, S.C.; Bulsara, M.K.; Patole, S.K. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in preterm infants: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20180134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.A.; Williams, S.; Patrick, M.E.; Valencia-Prado, M.; Durkin, M.S.; Howerton, E.M.; Ladd-Acosta, C.M.; Pas, E.T.; Bakian, A.V.; Bartholomew, P.; et al. Prevalence and Early Identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 4 and 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 16 Sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2025, 74, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttora, C.; Salerni, N. Gestural development and its relation to language acquisition in very preterm children. Infant Behav. Dev. 2012, 35, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBarton, E.S.; Iverson, J.M. Associations between gross motor and communicative development in at-risk infants. Infant Behav. Dev. 2016, 44, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansavini, A.; Guarini, A.; Zuccarini, M.; Lee, J.Z.; Faldella, G.; Iverson, J.M. Low Rates of Pointing in 18-Month-Olds at Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder and Extremely Preterm Infants: A Common Index of Language Delay? Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanika, L.; Boyer, W. Imitation and Social Communication in Infants. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfeld, S.; O’Connor, E.; Gray, S.; O’Connor, M.; on behalf of the Changing Children’s Chances Investigator Team. Addressing Disadvantage to Optimise Children’s Development in Australia. Research Snapshot #2; Centre for Community Child Health: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, S.M.; Booth, A.; Gee, M.; Salway, S.; Cobb, M.; Bhanbhro, S.; Nancarrow, S.A. Appointment Reminder Systems are Effective but Not Optimal: Results of a Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis Employing Realist Principles. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2016, 10, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, L.R.; Turner, K.M.; Morley, H.; Goldsworthy, L.; Sharp, D.J.; Hamilton-Shield, J. Characteristics of children who do not attend their hospital appointments, and GPs’ response: A mixed methods study in primary and secondary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 67, e483–e489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, J.; Dissanayake, C. Prospective identification of autism spectrum disorders in infancy and toddlerhood using developmental surveillance: The Social Attention and Communication Study. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2010, 31, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, J.; Dissanayake, C. Diagnostic stability of autism spectrum disorder in toddlers prospectively identified in a community-based setting: Behavioural characteristics and predictors of change over time. Autism 2017, 21, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | Number of Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 11 |

| Female | 14 | |

| Ethnicity | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | 4 |

| African | 0 | |

| Asian | 2 | |

| Caucasian | 11 | |

| Indian | 6 | |

| Maori | 0 | |

| Other | 2 | |

| Unknown | 4 | |

| Developmental delay in child being assessed | Present | 2 |

| Absent | 20 | |

| Unknown | 3 | |

| Siblings with ASD | Present | 1 |

| Absent | 22 | |

| Unknown | 2 | |

| Family history of ASD | Present | 10 |

| Absent | 14 | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Present; ADHD Only | 5 | |

| Present; ADHD and others | 1 | |

| Present; Speech and Learning Delays | 2 | |

| Absent | 15 | |

| Unknown | 2 | |

| Language spoken at home | English Only | 15 |

| English as the Primary Language + Additional Language(s) | 4 | |

| English as the Secondary Language + Additional Languages(s) | 5 | |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Maternal level of education | Primary | 0 |

| Completed yr 10 | 2 | |

| Completed yr 12 | 7 | |

| Tertiary and above | 16 | |

| Paternal level of education | Primary | 1 |

| Completed yr 10 | 2 | |

| Completed yr 12 | 6 | |

| Tertiary and above | 16 | |

| Maternal comorbidities @ | Diabetes | 10 |

| Pre-eclampsia | 4 | |

| Chorioamnionitis | 4 | |

| Neurobehavioral Issues | 5 | |

| PPROM/oligohydramnios | 2 | |

| None | 8 | |

| Clinician Acceptability [n (%)] n=12 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were you satisfied with the use of SACS-R tool? | Very Unsatisfied | Unsatisfied | No Opinion | Satisfied | Very Satisfied |

| 1 (8) | 0 | 1 (8) | 7 (58) | 3 (25) | |

| Given the choice, would you be likely to continue using it? | Very Unlikely | Unlikely | No Opinion | Likely | Very Likely |

| 0 | 0 | 2 (16) | 5 (41) | 5 (41) | |

| Do you think it is appropriate/ethical to use SACS-R tool? (n = 11) | Very Inappropriate | Inappropriate | No Opinion | Appropriate | Very Appropriate |

| 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 3 (25) | 7 (58) | |

| Using the SACS-R tool improves the value of neonatal follow-up: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 0 | 0 | 3 (25) | 6 (50) | 3 (25) | |

| Using the SACS-R tool is a positive change for neonatal follow-up | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 0 | 0 | 3 (25) | 5 (41) | 4 (33) | |

| How confident did you feel using the SACS-R | Not at all | Slightly Confident | Neutral | Reasonably Confident | Very Confident |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (66) | 4 (33) | |

| I felt confident in the results of the SACS-R (n = 11) | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 6 (50) | 4 (33) | |

| How much effort did it take to complete the SACS-R tool? | No effort at all | A little effort | No Opinion | A lot of effort | Huge effort |

| 1 (8) | 9 (75) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 0 | |

| Completing the SACS-R is a worthwhile use of clinical time: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 0 | 0 | 4 (33) | 4 (33) | 4 (33) | |

| Clinician Open-Ended Comments on the Best & Worst Issues about the SACS-R tool | Area of Feedback |

|---|---|

| Best—using an ASD screening tool is a really good idea for neonatal follow-up. I believe it will improve rates of kids accessing appropriate early intervention services | Value of ASD specific screening tool |

| I don’t know how well validated and sensitive this specific tool is, but I definitely think an ASD screening tool needs to be used at all points in Neonatal follow-up | |

| I can’t comment on this specific tool having value over other ASD screening tools; however, I do feel that adding a dedicated caregiver ASD screening tool increases the value of our follow-up | |

| Important Screening tool as not all parents may be aware of ASD signs | |

| I didn’t specifically ask if parents were “happy”, but completing the tool certainly seemed acceptable and reasonable to parents | Parent Feedback |

| Clinician Open-Ended Comments on the Best & Worst Issues about the SACS-R tool | Area of Feedback |

|---|---|

| I used SACS-R tool only couple of times that too in a busy clinic while dealing with complex patients so it’s difficult to comment | Challenging complex clinic environment |

| Related audit tools took some time but questionnaire quick | Length of questionnaires |

| I think the parents’ questionnaire could be shortened. It takes longer than the SACS-R | |

| Some assessments take much more time than others. It would probably be appropriate/ideal if this tool was sent out in advance along with the ASQ (and an appropriate accompanying explanation of what the tool was and how to complete it) | Ensuring parental understanding of tool |

| Worst issues—no accompanying explanation for parents, so relies on the clinician’s explanation. I had no opportunity to explore the process of addressing the issue further if the tool screens positive, hence can’t comment on this | |

| Should continue using this tool, but WITH some preamble text to explain purpose to parents | |

| The name of the tool & title on the top of the pages makes no mention of Autism—took some time to explain this and the value of early diagnosis & intervention—would be good if this was included | |

| None issues but all the ones I completely did not flag increased risk of ASD. If parents had no concerns themselves but the tool screened positive it may take some time to explain the results and address any questions | Complexity in results explanation |

| No worst issues but it will only be worthwhile if the best is shown to identify high risk patients in our setting and if we have someone to refer them to. | Sensitivity of SACS-R tool, Clarity about Follow-up Referrals |

| I don’t think it adds much to the clinical and developmental assessments. | Overlap with other developmental assessment tools |

| All items are already covered in Griffiths developmental assessment. Just need to get familiarity with the items on the checklist. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Athalye-Jape, G.; Pillar, S.; Saminathan, S.; Wu, K.; Sherrard, S.; Dudman, E.; Sharp, M. Evaluation of the Acceptability and Feasibility of the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance-Revised (SACS-R) Tool for Early Identification of Autism in Preterm Infants: The Identify and Act Study. Children 2025, 12, 1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091130

Athalye-Jape G, Pillar S, Saminathan S, Wu K, Sherrard S, Dudman E, Sharp M. Evaluation of the Acceptability and Feasibility of the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance-Revised (SACS-R) Tool for Early Identification of Autism in Preterm Infants: The Identify and Act Study. Children. 2025; 12(9):1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091130

Chicago/Turabian StyleAthalye-Jape, Gayatri, Sarah Pillar, Sudharshana Saminathan, Kexian Wu, Stephanie Sherrard, Emma Dudman, and Mary Sharp. 2025. "Evaluation of the Acceptability and Feasibility of the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance-Revised (SACS-R) Tool for Early Identification of Autism in Preterm Infants: The Identify and Act Study" Children 12, no. 9: 1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091130

APA StyleAthalye-Jape, G., Pillar, S., Saminathan, S., Wu, K., Sherrard, S., Dudman, E., & Sharp, M. (2025). Evaluation of the Acceptability and Feasibility of the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance-Revised (SACS-R) Tool for Early Identification of Autism in Preterm Infants: The Identify and Act Study. Children, 12(9), 1130. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12091130