Abstract

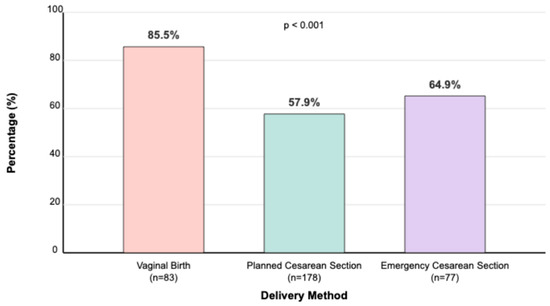

Background/Objectives: Cesarean delivery often leads to delayed breastfeeding initiation, potentially affecting infant health compared with vaginal delivery. This prospective observational study (conducted between August 2022 and January 2024) comparatively evaluates the impact of delivery method—vaginal, planned cesarean, and emergency cesarean—on breastfeeding initiation and continuation and examines the maternal factors influencing these outcomes. Materials and Methods: We enrolled 338 mother–infant pairs at a tertiary university hospital. Breastfeeding effectiveness was assessed using the Bristol Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (BBAT) at birth and at one, three, and six months postpartum. Rates of breastfeeding continuation and formula supplementation were documented through structured interviews. Results: The mothers who delivered vaginally had a significantly higher rate of breastfeeding within one hour after birth (85.5%) compared with planned (57.9%) and emergency cesarean sections (64.9%) (p < 0.001). Baseline BBAT scores were higher for vaginal births but converged across the groups by one month postpartum (p > 0.05). At six months, breastfeeding continuation rates remained high (94.4–95.2%) irrespective of delivery method. Conclusions: Delivery method exerts a transient effect on breastfeeding initiation. With lactation support, the mothers delivering by cesarean section achieved comparable breastfeeding outcomes within the first month postpartum. These findings reinforce the importance of Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) practices, including immediate skin-to-skin contact, effective pain management, and lactation counseling, in ensuring equitable breastfeeding outcomes.

1. Introduction

Breastfeeding is universally recognized as a cornerstone of maternal and child health, providing optimal nutrition, enhancing immunity, and supporting cognitive and physical development in infants. It also confers significant maternal benefits, including a reduced risk of postpartum hemorrhage, certain cancers, and metabolic disorders [1,2]. Consequently, global health authorities such as the WHO and UNICEF recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months and continuation up to two years or beyond, aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targeting child survival and well-being [3,4]. However, global rates of exclusive breastfeeding remain below the 60% target set for 2030, reflecting ongoing challenges in achieving equitable breastfeeding practices worldwide [5]. Delivery method has emerged as a key determinant of breastfeeding outcomes. Vaginal delivery facilitates immediate mother–infant bonding through natural hormonal surges, such as oxytocin release, which enhances lactation [6]. In contrast, cesarean section (C/S)—whether planned (elective) or performed emergently—can interfere with these physiological processes. Planned C/S, often scheduled before the onset of labor, lacks the hormonal priming of vaginal delivery, whereas emergency C/S, performed after labor begins, may partially preserve these effects but is frequently complicated by maternal fatigue, anesthesia, and surgical stress [7,8].

Current evidence suggests that both types of cesarean delivery are associated with the delayed initiation of breastfeeding compared with vaginal delivery, yet their relative impacts remain insufficiently explored [9,10]. Moreover, “Baby-Friendly Hospital” practices, including early skin-to-skin contact and immediate breastfeeding support, have been shown to mitigate some of the breastfeeding challenges associated with cesarean delivery [11,12]. Despite these interventions, cesarean delivery rates continue to rise globally, driven by both medical indications and non-medical factors, raising concerns about the potential downstream effects on breastfeeding practices [13]. Existing studies often fail to distinguish between planned and emergency cesarean deliveries when evaluating breastfeeding outcomes, leading to conflicting conclusions about the long-term impact of delivery method on breastfeeding continuation [14,15]. Furthermore, sociodemographic factors, such as maternal education and support systems, may modify these effects but are rarely controlled for in analyses [16,17,18].

This prospective evaluation of breastfeeding outcomes across delivery modes addresses a critical global health challenge, aligning with the WHO’s Global Breastfeeding Collective targets and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 2, 3, and 5) [6]. By distinguishing between planned and emergency cesarean deliveries, incorporating structured breastfeeding assessments, and controlling for key maternal and perinatal factors [19], this study provides nuanced insights into whether cesarean-related breastfeeding challenges are transient and modifiable. These findings have both methodological and practical significance for guiding targeted postpartum support interventions in settings with rising cesarean rates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This prospective observational cohort study was conducted between August 2022 and January 2024 at a tertiary Baby-Friendly hospital in Tekirdağ, Türkiye. The hospital’s designation as Baby-Friendly aligns with national policies supporting breastfeeding practices and the WHO’s Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (Approval No. 2022.135.07.02, Date: 26 July 2022). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. For mothers aged 16–17 years, consent from a legal guardian was additionally secured to ensure voluntary participation.

2.3. Participants

Participant inclusion criteria: Mothers aged 16–51 years who gave birth at ≥37 weeks of gestation during the study period and were willing to participate.

Exclusion criteria: Mothers with prior breastfeeding difficulties, previous breast surgery, or medical conditions contraindicating breastfeeding (e.g., HIV infection). The relatively high proportion of planned cesarean sections (52.7%) reflects local obstetric practices where elective C/S is often performed due to maternal request or perceived fetal risks, in line with national trends showing rising elective C/S rates.

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

Sample size calculation: The required sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1 (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany), targeting an effect size of 0.25, power of 80%, and alpha of 0.05 for detecting differences in breastfeeding outcomes across three delivery methods. A minimum of 300 mother–infant pairs was determined to be sufficient; 338 were ultimately enrolled.

2.5. Data Collection and Instruments

Breastfeeding effectiveness was assessed using the Bristol Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (BBAT), developed in 2015 [20]. The BBAT has been validated for use in Turkey [21] with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 in our study population, indicating high internal consistency. The BBAT evaluates four domains, positioning, attachment, sucking, and swallowing, each scored from 0 (poor) to 2 (good), for a total score range of 0–8. A structured interview form, developed by the research team based on Ministry of Health guidelines, was used to collect sociodemographic data, breastfeeding continuation rates, and formula supplementation information.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics included means ± standard deviation (SD) and percentages. Normality was assessed via the Shapiro–Wilk test. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction was used for continuous variables; chi-square tests for categorical variables. Repeated measures ANOVA evaluated changes in BBAT scores over time. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 338 mothers aged 16 to 51 years (mean 28.2 ± 4.2 years, range: 16–51) participated in the study. The majority were housewives (77.5%), and 17.8% had a university-level education. The mean pregestational BMI was 26.2 ± 3.2 kg/m2 (range: 19.1–34.8), and mean weight gain during pregnancy was 14.8 ± 4.8 kg (range: 7–27). The sociodemographic characteristics by delivery method are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population (n = 338).

Overall, 98.5% of mothers initiated breastfeeding postpartum. However, the timing of initiation varied significantly by delivery method (p < 0.001): 85.5% of vaginal deliveries initiated breastfeeding within one hour, compared with 57.9% in planned cesarean sections and 64.9% in emergency cesarean sections (Figure 1). Over time, breastfeeding continuation rates remained high across the groups, with 95.9% at three months and 94.7% at six months postpartum. Concurrently, the use of formula supplementation and complementary foods gradually increased, reaching 17.8% and 24.3%, respectively, at six months. The proportion of mothers returning to work was minimal (0.6%) during the first three months, rising slightly to 4.4% by six months postpartum.

Figure 1.

Proportion of mothers initiating breastfeeding within 1 h by delivery method. Percentage (%) of mothers initiating breastfeeding within 1 h. Delivery methods: vaginal birth, planned cesarean section, and emergency cesarean section. World Health Organization (WHO) [6] defines early initiation of breastfeeding as breastfeeding within the first hour after birth.

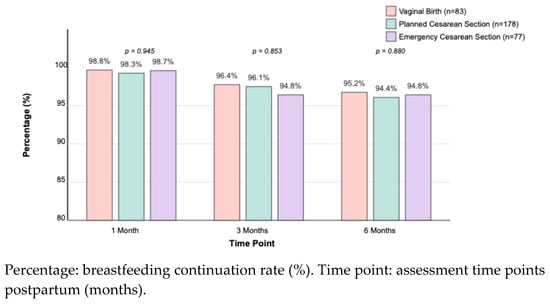

By one month postpartum, breastfeeding continuation rates were similarly high across the groups (vaginal: 98.8%, planned C/S: 98.3%, emergency C/S: 98.7%; p = 0.945). These high rates persisted at three months (vaginal: 96.4%, planned C/S: 96.1%, emergency C/S: 94.8%; p = 0.853) and six months postpartum (vaginal: 95.2%, planned C/S: 94.4%, emergency C/S: 94.8%; p = 0.880) (Figure 2). No significant differences were found between the groups in breastfeeding continuation rates at these later time points, highlighting that early disparities in initiation were transient (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Breastfeeding continuation rates at 1, 3, and 6 months postpartum, by delivery method. Values represent the percentage of mothers continuing breastfeeding at each time point.

At one month postpartum, formula supplementation rates were 13.3% in the vaginal delivery group, 16.9% in the planned C/S group, and 16.9% in the emergency C/S group (p = 0.724). These rates slightly increased by six months postpartum (vaginal: 16.9%, planned C/S: 18.0%, emergency C/S: 18.2%; p = 0.967). The proportion of infants receiving complementary foods at six months was also comparable across the groups (vaginal: 24.1%, planned C/S: 24.2%, emergency C/S: 24.7%; p = 0.995) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Breastfeeding outcomes by delivery method (vaginal birth, planned cesarean section, and emergency cesarean section).

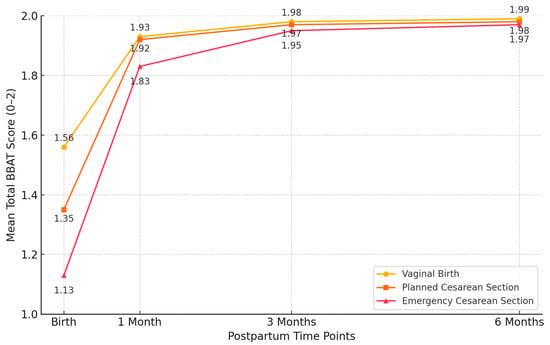

Significant differences were observed in baseline BBAT scores among the delivery methods. Vaginal deliveries had the highest mean total BBAT score at birth (1.56 ± 0.34; range: 0.9–2.0), followed by planned C/S (1.35 ± 0.33; range: 0.8–1.9), and emergency C/S (1.13 ± 0.38; range: 0.7–1.8) (p < 0.001).

By one month postpartum, these differences diminished, with mean BBAT scores converging across the groups (vaginal: 1.93 ± 0.19; range: 1.5–2.0, planned C/S: 1.92 ± 0.20; range: 1.4–2.0, emergency C/S: 1.83 ± 0.23; range: 1.3–2.0; p = 0.068). At three and six months postpartum, BBAT scores remained high and comparable between the groups (p = 0.466 and p = 0.751, respectively), suggesting that early challenges in breastfeeding technique were overcome with time and support (Figure 3, Table 3).

Figure 3.

Total Bristol Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (BBAT) scores by delivery method at different time points. BBAT scores range from 0 to 2, with higher scores indicating better breastfeeding technique.

Table 3.

Bristol Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (BBAT) scores by delivery method at different time points.

Repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated significant improvements in BBAT scores within each delivery group over time (p < 0.001 for all groups). The emergency cesarean section group exhibited the largest relative improvement in total BBAT scores from birth to six months (74.3% increase), followed by planned C/S (46.7%) and vaginal delivery (27.6%). A significant time × delivery method interaction (p < 0.001) indicated differential recovery trajectories among the groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Within-group temporal changes in BBAT components by delivery method: repeated measures ANOVA results.

The correlation analysis revealed significant associations between maternal and perinatal factors and breastfeeding outcomes. Immediate skin-to-skin contact was negatively correlated with NICU admission (r = −0.798, p < 0.001), and also showed a weak but statistically significant negative correlation with BBAT scores at birth (r = −0.117, p = 0.032), indicating a potential link with early breastfeeding effectiveness. Baseline BBAT scores positively correlated with newborn birth weight (r = 0.377, p < 0.001). Interestingly, a positive correlation was also found with NICU admission (r = 0.321, p < 0.001), which may reflect increased breastfeeding support efforts or maternal motivation in cases where infants required NICU care. The regression analysis revealed that maternal education level accounted for only 3.2% of the variance in BBAT scores at birth and 2.7% of the variance in breastfeeding continuation at six months postpartum (adjusted R2 values). These findings were not statistically significant (p > 0.05), indicating limited predictive value. At six months postpartum, these associations had weakened and were no longer statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation analysis of key factors affecting breastfeeding outcomes.

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the impact of the method of delivery on breastfeeding initiation rates and breastfeeding duration as well as the rates of immediate skin-to-skin contact and mothers’ education level. Notably, we found the overall breastfeeding initiation rate to be 98.5% in our study group, which is substantially higher than the global average of 41.6% [22]. Although early initiation within one hour postpartum is a key WHO indicator, our findings suggest that structured postpartum support may mitigate initial delays, underscoring the need for tailored lactation programs, particularly for cesarean deliveries. This aligns with previous studies reporting that postpartum support interventions significantly improve breastfeeding outcomes irrespective of delivery method [23]. In parallel, another study reported that the breastfeeding initiation rate in low-resource settings was 81.5%, and the breastfeeding continuation rate at six months postpartum was 70.5% [24].

4.1. Mothers’ Demographic Characteristics and Breastfeeding Outcomes

The mothers’ demographic characteristics, such as education level, profession, and pregestational BMI, had an impact on breastfeeding practices. Mothers’ educational level reportedly has a modest secondary effect on breastfeeding outcomes, considering other contributing factors [25], as higher education levels were positively correlated with infant feeding outcomes. Studies conducted in Nigeria and Morocco have reported a positive correlation between higher education levels and increased breastfeeding knowledge among mothers [26,27]. These findings may be attributed to the fact that mothers with higher levels of education potentially become more knowledgeable about breastfeeding and have easier access to breastfeeding support, therefore they tend to have greater awareness about breastfeeding and are more likely to exclusively breastfeed their babies [28]. However, our regression analyses revealed that the mothers’ education level explained only a minimal amount of the variance in breastfeeding behaviors, as detailed in the Results section, suggesting that other factors, such as family support, the accessibility of healthcare services, and maternal motivation, are perhaps more crucial to breastfeeding success.

4.2. Breastfeeding Support and Breastfeeding Outcomes

Flexible or supportive practices for breastfeeding in the workplace have been associated with higher rates of breastfeeding among the mothers who work outside the home [27]. The low rates of working mothers (22.5%) and mothers returning to work at three (0.6%) and six (4.4%) months postpartum in our sample may have contributed to the high rates of breastfeeding we observed throughout the study period.

Several studies have shown that the method of delivery significantly affects breastfeeding outcomes, especially during the initial period after birth. One of these studies revealed that those who had an assisted vaginal birth were less likely to breastfeed at three months postpartum compared with those who had an unassisted vaginal birth [29]. Cesarean section deliveries may reportedly delay breastfeeding initiation in infants compared with vaginal deliveries due to difficulties in acquiring the motor skills for effective latching and sucking [30]. Variations in early bonding, skin-to-skin contact, and maternal comfort after cesarean section delivery may also influence breastfeeding outcomes [31]. Basic training specifically designed for mothers with a high BMI may also improve breastfeeding knowledge and skills, enabling women to breastfeed for longer periods [32]. These findings emphasize the critical role of Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) practices, such as immediate skin-to-skin contact, early rooming-in, and structured lactation counseling, especially for mothers who deliver via cesarean section. Hospitals should ensure that post-cesarean mothers receive targeted support from trained lactation consultants to mitigate early challenges and promote sustained breastfeeding [33,34].

4.3. Method of Delivery and Breastfeeding Outcomes

Our findings clearly demonstrated that the method of delivery is a major factor in breastfeeding initiation. Babies born via emergency cesarean section tend to be born with more primitive motor activity at birth than babies born via vaginal delivery and planned cesarean section. Then again, babies’ developmental systems recover well, and early postnatal interventions may also be effective [35]. The differences in breastfeeding rates depending on the method of delivery are most pronounced after birth and gradually become insignificant as motor skills become more consistent at three and six months postpartum, emphasizing the need for targeted postpartum breastfeeding support, particularly for mothers and infants who experienced an emergency cesarean delivery [36].

Our findings regarding the impact of the delivery method on breastfeeding initiation are consistent with the existing literature. Babies born by cesarean section, especially emergency cesarean section, often have difficulty initiating breastfeeding, primarily due to delayed skin-to-skin contact and the effects of anesthesia on neonatal reflexes [37,38]. It is important to acknowledge that the timing of breastfeeding initiation within the first hour postpartum, although widely recommended by WHO and other global health organizations as a key indicator, may not universally predict long-term breastfeeding success. The variability in maternal and neonatal factors should be considered when interpreting this outcome. Nevertheless, early initiation has been associated with improved neonatal survival and reduced morbidity, making it a critical component of postpartum care [6]. In our cohort, while early initiation rates varied significantly by delivery method, the convergence of breastfeeding continuation rates at later time points suggests that initial delays can be mitigated through structured postpartum support. On the other hand, our study differs from previous studies, which reported that the adverse effects of cesarean section on the breastfeeding outcomes of infants were permanent, as we showed that the adverse impact of cesarean section on the breastfeeding outcomes of infants became insignificant at three and six months postpartum compared with vaginal delivery. As a matter of fact, postnatal support and external factors reportedly mediate long-term breastfeeding success [39]. Furthermore, our data indicate that although cesarean delivery initially delays breastfeeding initiation, by six months postpartum, breastfeeding continuation rates were comparable across all delivery methods, highlighting that the delivery mode’s impact diminishes over time. Moreover, our findings reporting a relatively weak predictive value for mothers’ education level on breastfeeding outcomes also suggests that breastfeeding success depends on many factors. Finally, our effective use of BBAT in a clinical setting to determine how the method of delivery and maternal factors affect breastfeeding outcomes shows that breastfeeding assessment tools can be effectively integrated into routine postpartum care.

Our study’s primary strength lies in its prospective cohort design, which minimizes recall bias and allows for the structured, time-sensitive observation of breastfeeding behaviors during the critical postpartum period. The systematic follow-up of participants from birth to six months allowed for the capture of temporal changes in breastfeeding dynamics and provided a more robust understanding of early feeding practices compared with cross-sectional studies.

Using validated BBAT as an assessment tool further strengthened our methodological rigor. Such tools ensure the standardized evaluation of key breastfeeding components, enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of the findings. Additionally, by comparatively reviewing various delivery methods, i.e., vaginal delivery, planned cesarean section, and emergency cesarean section, we address a significant gap in the existing literature and provide a comprehensive perspective on how different obstetric contexts affect breastfeeding outcomes.

In addition to its strengths, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the predictor variables were intentionally kept narrow to focus on delivery method and immediate postpartum breastfeeding outcomes. Secondly, the data on breastfeeding practices beyond BBAT scoring were self-reported, introducing potential recall and social desirability biases. Thirdly, the single-center design limits the generalizability to other populations and institutional settings. Finally, as an observational study, randomization was not feasible, and the delivery method was dictated by clinical indications, limiting the ability to infer causality. These limitations reflect real-world clinical practice and highlight the need for future multicenter randomized trials with objective measures of breastfeeding success.

4.4. Limitations

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. As it was conducted at a single tertiary-level Baby-Friendly hospital, the generalizability of the findings to other clinical settings or healthcare systems may be limited. While the prospective design and structured follow-up improved data reliability, residual confounding factors such as maternal motivation, psychological well-being, or informal family support may still have influenced breastfeeding outcomes. Additionally, self-reported breastfeeding practices are prone to recall and social desirability biases, particularly over long-term follow-up. The Bristol Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (BBAT), although validated, primarily assesses the technical aspects of feeding and may not capture broader psychosocial dimensions. Moreover, the early initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour postpartum, while a key WHO indicator, may not universally predict long-term success, which is a contextual limitation. Finally, as an observational study, randomization was not feasible, and the delivery method was dictated by clinical indications, limiting causal inference. Recognizing these limitations is crucial for interpreting our results and guiding future multicenter randomized trials with diverse populations and objective measures of breastfeeding success.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights that while cesarean delivery—particularly emergency cesarean section—can initially delay breastfeeding initiation, these early challenges do not persist beyond the postpartum period. By six months, breastfeeding continuation rates were comparable across all delivery methods, underscoring the critical role of structured postpartum support. These findings reinforce the importance of Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) practices, including immediate skin-to-skin contact, effective pain management, and lactation counseling, in ensuring equitable breastfeeding outcomes. Future efforts should focus on developing targeted post-cesarean support programs and evaluating their long-term impact through multicenter studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, İ.Ö.A. and M.T.A.; methodology, İ.Ö.A. and M.T.A.; validation, M.T.A. and N.Ç.; formal analysis, M.T.A. and N.Ç.; investigation, İ.Ö.A., M.T.A., N.C. and Ö.S.E.; resources, N.C. and Ö.S.E.; data curation, İ.Ö.A.; writing—original draft preparation, İ.Ö.A.; writing—review and editing, M.T.A., Ö.S.E. and N.Ç.; supervision, İ.Ö.A.; project administration, İ.Ö.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University Faculty of Medicine (approval No. 2022.135.07.02, date: 26 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to national restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BBAT | Bristol Breastfeeding Assessment Tool |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BFHI | Baby-Friendly Hospital Initative |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Ajmal, R. Promoting Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Practices for Optimal Maternal and Child Nutrition. Pak. J. Public Health 2024, 14, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, A.; Ronghe, V.; Gomase, K.P.; Modak, A.; Ronghe, V.; Dukare, K.P. The Psychological Benefits of Breastfeeding: Fostering Maternal Well-Being and Child Development. Cureus 2023, 15, e46730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Thapar, R.K.; Gupta, R.K. Complete Coverage and Covering Completely: Breast Feeding and Complementary Feeding: Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Mothers. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2018, 74, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Board on Neuroscience, Behavioral Health, Committee on Health, Practice. Health and Behavior: The Interplay of Biological, Behavioral, and Societal Influences; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, C.E.; Hanley, L.E. Barriers to Breastfeeding: Supporting Initiation and Continuation of Breastfeeding. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 137, E54–E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization & United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Global Breastfeeding Scorecard 2022: Protecting Breastfeeding Through Further Investments and Policy Actions. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HEP-NFS-22.6 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Hobbs, A.J.; Mannion, C.A.; McDonald, S.W.; Brockway, M.; Tough, S.C. The Impact of Caesarean Section on Breastfeeding Initiation, Duration and Difficulties in the First Four Months Postpartum. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedefaw, G.; Goedert, M.H.; Abebe, E.; Demis, A. Effect of Cesarean Section on Initiation of Breast Feeding: Findings from 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adane, M.; Zewdu, S. Timely Initiation of Breastfeeding and Associated Factors among Mothers with Vaginal and Cesarean Deliveries in Public Hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Clin. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 5, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getaneh, T.; Negesse, A.; Dessie, G.; Desta, M.; Temesgen, H.; Getu, T.; Gelaye, K. Impact of Cesarean Section on Timely Initiation of Breastfeeding in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior, E.; Santhakumaran, S.; Gale, C.; Philipps, L.H.; Modi, N.; Hyde, M.J. Breastfeeding after Cesarean Delivery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of World Literature. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1113–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulfa, Y.; Maruyama, N.; Igarashi, Y.; Horiuchi, S. Early Initiation of Breastfeeding up to Six Months among Mothers after Cesarean Section or Vaginal Birth: A Scoping Review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, J.; Thompson, A.; Defranco, E. The Influence of Mode of Delivery on Breastfeeding Initiation in Women with a Prior Cesarean Delivery: A Population-Based Study. Breastfeed. Med. 2013, 8, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, S.; Sword, W.; Sheehan, D.; Foster, G.; Thabane, L.; Krueger, P.; Landy, C.K. The Effect of Delivery Method on Breastfeeding Initiation from the The Ontario Mother and Infant Study (TOMIS) III. JOGNN—J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 41, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Appleton, R.; Hutchings-Hay, C.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Johnson, S. A Systematic Review of Influences on Implementation of Supported Self-Management Interventions for People with Severe Mental Health Problems in Secondary Mental Health Care Settings. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabhart, J.M.; Wasio, L.N.; U-thaiwat, P.; Chen, Y.W.; Main, J. A Live Online Prenatal Educational Model: Association with Exclusive Breastfeeding at Discharge. J. Hum. Lact. 2025, 41, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.S.; Alexander, D.D.; Krebs, N.F.; Young, B.E.; Cabana, M.D.; Erdmann, P.; Hays, N.P.; Bezold, C.P.; Levin-Sparenberg, E.; Turini, M.; et al. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. 2018, 203, 190–196.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelbrecht, A.; Gruffi, L.; Silver, M.; Lax, Y. Initial Feeding Method, WIC-Provided Lactation Support, and Breastfeeding Duration at an Urban Pediatric Primary Care Practice. J. Community Health 2024, 49, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallick, L.M.; Shenassa, E.D. Variation in Breastfeeding Initiation and Duration by Mode of Childbirth: A Prospective, Population-Based Study. Breastfeed. Med. 2024, 19, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, J.; Johnson, D.; Copeland, M.; Churchill, C.; Taylor, H. The development of a new breast feeding assessment tool and the relationship with breast feeding self-efficacy. Midwifery 2015, 31, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgun, G.; İnal, S.; Erdim, L.; Korkut, S. Reliability and validity of the Bristol Breastfeeding Assessment Tool in the Turkish population. Midwifery 2018, 57, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Infant and Young Child Feeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Balogun, O.O.; Dagvadorj, A.; Yourkavitch, J.; Da Silva Lopes, K.; Suto, M.; Takemoto, Y.; Mori, R.; Rayco-Solon, P.; Ota, E. Health Facility Staff Training for Improving Breastfeeding Outcome: A Systematic Review for Step 2 of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. Breastfeed. Med. 2017, 12, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuita, F.; Mukuria, A.; Muhomah, T.; Locklear, K.; Grounds, S.; Martin, S.L. Fathers and Grandmothers Experiences Participating in Nutrition Peer Dialogue Groups in Vihiga County, Kenya. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulahi, M.; Fretheim, A.; Argaw, A.; Magnus, J.H. Breastfeeding Education and Support to Improve Early Initiation and Exclusive Breastfeeding Practices and Infant Growth: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial from a Rural Ethiopian Setting. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeola, O.A.; Mojisola, A.A.; Jamila, Y. Impact of Maternal Demographics on Knowledge of Exclusive Breastfeeding among Nursing Mothers in Ifelodun Local Government, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2023, 23, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, M.; Laamiri, F.Z.; Aguenaou, H.; Doukkali, L.; Mrabet, M.; Barkat, A. The Impact of Maternal Sociodemographic Characteristics on Breastfeeding Knowledge and Practices: An Experience from Casablanca, Morocco. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2018, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaghan, S.; Moore, R.L.; Geraghty, A.A.; Yelverton, C.; McAuliffe, F. Examination of Weight Status, Parity and Maternal Education Factors on Intentions to Breastfeed and Breastfeeding Duration in an Irish Cohort. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, E158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, L.Y.; Tai, C.J. Effect of Delivery Method and Timing of Breastfeeding Initiation on Breastfeeding Outcomes in Taiwan. Birth 2007, 34, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krassioukov, A.; Elliott, S.; Hocaloski, S.; Krassioukova-Enns, O.; Hodge, K.; Gillespie, S.; Caves, S.; Thorson, T.; Alford, L.; Basso, M.; et al. Motherhood after Spinal Cord Injury: Breastfeeding, Autonomic Dysreflexia, and Psychosocial Health: Clinical Practice Guidelines. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2024, 30, 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rol, M.J.; Cuerva, M.J.; Angeles Palomares, M.d.l.; Vallecillo, C.; Franke, S.; Bartha, J.L. Impact of Peripartum Depression and Anxiety Symptoms on Unplanned Cesarean or Operative Vaginal Births: A Prospective Observational Study. Clin. Exp. Obs. Gynecol. 2024, 51, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, L.T.; Zackula, R.E.; Lu, K. Effectiveness of a Pilot Breastfeeding Educational Intervention Targeting High BMI Pregnant Women. Kans. J. Med. 2020, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maastrup, R.; Hannula, L.; Hansen, M.N.; Ezeonodo, A.; Haiek, L.N. The Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative for neonatal wards. A mini review. Acta Paediatr. 2022, 111, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.W.; Fan, H.S.L.; Shing, J.S.Y.; Ip, H.L.; Fong, D.Y.T.; Lok, K.Y.W. Impact of baby-friendly hospital initiatives on breastfeeding outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Women Birth 2025, 38, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaigham, M.; Hellström-Westas, L.; Domellöf, M.; Andersson, O. Prelabour Caesarean Section and Neurodevelopmental Outcome at 4 and 12 Months of Age: An Observational Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ares, G.; De Rosso, S.; Mueller, C.; Philippe, K.; Pickard, A.; Nicklaus, S.; van Kleef, E.; Varela, P. Development of Food Literacy in Children and Adolescents: Implications for the Design of Strategies to Promote Healthier and More Sustainable Diets. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 82, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaplin, J.; Kelly, J.; Kildea, S. Maternal Perceptions of Breastfeeding Difficulty after Caesarean Section with Regional Anaesthesia: A Qualitative Study. Women Birth 2016, 29, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smitha, M.V.; Priyadarshini, T.; Sandhya, K.; Jyoti, S.; Angel, J.; Ashitha, K.; Premlata, C.; Sabarni, B. Effect of Breastfeeding Support Initiative on Knowledge, Breast Engorgement, and Newborn Feeding Behavior among Post-Cesarean Mothers. Manipal J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2023, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Yuan, J.; Lok, K.Y.W.; Ngu, S.F.; Chen, Y.; Lam, W.W.T. Learning from Mothers’ Success in Breastfeeding Maintenance: Coping Strategies and Cues to Action. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1167272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).