COVID-19 Stress and Family Well-Being: The Role of Sleep in Mental Health Outcomes for Parents and Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics

2.3.2. Pandemic-Related Stress

2.3.3. Child and Parent Mental Health

2.3.4. Sleep

2.4. Data Analysis

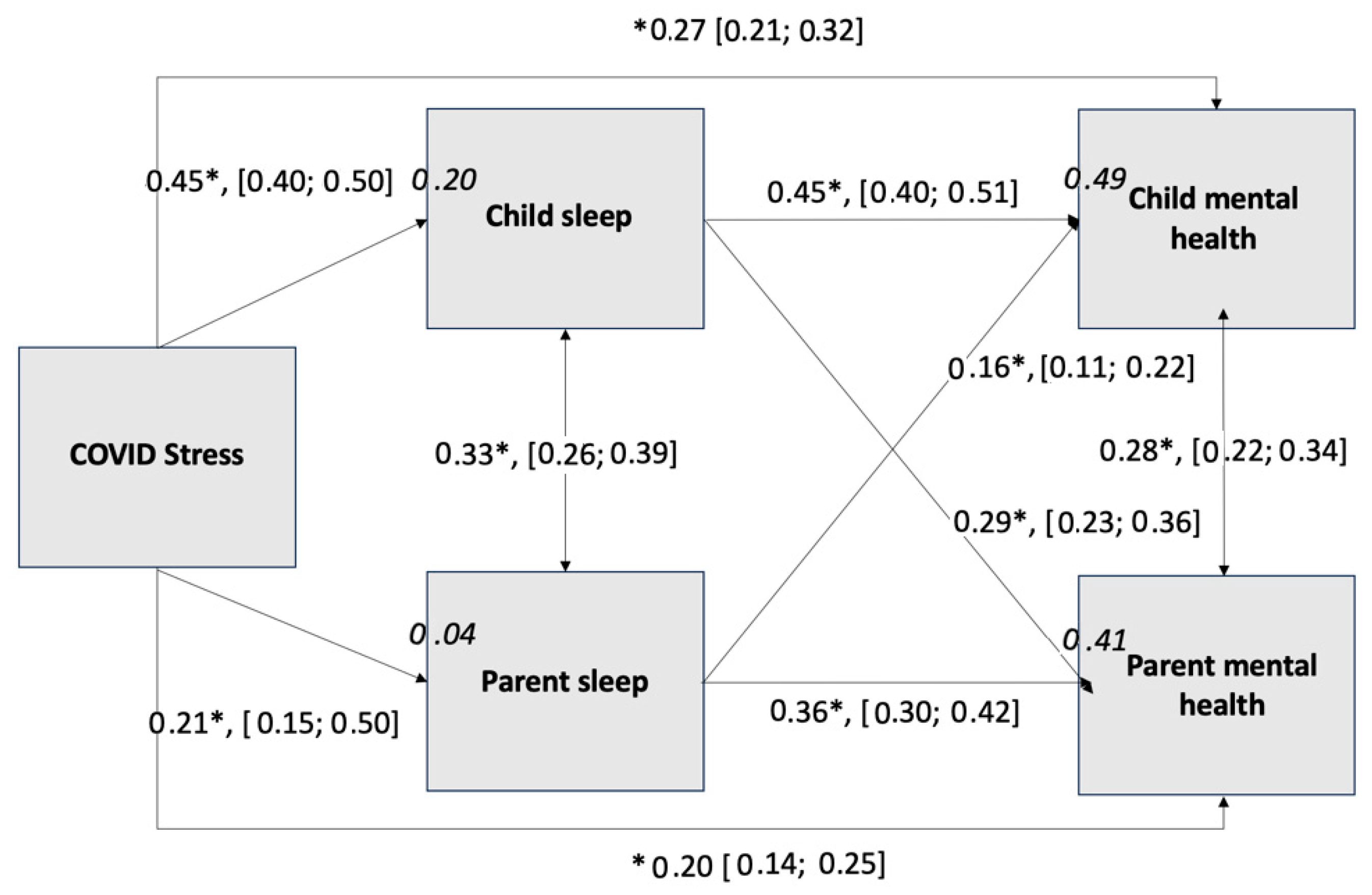

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Implications

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease of 2019 |

References

- Filip, R.; Gheorghita Puscaselu, R.; Anchidin-Norocel, L.; Dimian, M.; Savage, W.K. Global Challenges to Public Health Care Systems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of Pandemic Measures and Problems. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyah, Y.; Benjelloun, M.; Lairini, S.; Lahrichi, A. COVID-19 Impact on Public Health, Environment, Human Psychology, Global Socioeconomy, and Education. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 5578284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassman-Pines, A.; Ananat, E.O.; Fitz-Henley, J.; Leer, J. Effect of Daily School and Care Disruptions during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Child Behavior Problems. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 58, 1512–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selman, S.B.; Dilworth-Bart, J.E. Routines and Child Development: A Systematic Review. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2024, 16, 272–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadermann, A.C.; Thomson, K.C.; Richardson, C.G.; Gagné, M.; McAuliffe, C.; Hirani, S.; Jenkins, E. Examining the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Mental Health in Canada: Findings from a National Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, N.E.; Keys, E.; Hall, W.A.; Gruber, R.; Smith, I.M.; Constantin, E.; Godbout, R.; Stremler, R.; Reid, G.J.; Hanlon-Dearman, A.; et al. Children’s Sleep During COVID-19: How Sleep Influences Surviving and Thriving in Families. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büber, A.; Aktaş Terzioğlu, M. Caregiver’s Reports of Their Children’s Psychological Symptoms after the Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Caregiver’s Perceived Stress in Turkey. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2022, 76, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkart, K.G.; Brauer, M.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Godwin, W.W.; Hay, S.I.; He, J.; Iannucci, V.C.; Larson, S.L.; Lim, S.S.; Liu, J.; et al. Estimating the Cause-Specific Relative Risks of Non-Optimal Temperature on Daily Mortality: A Two-Part Modelling Approach Applied to the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2021, 398, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maximova, K.; Khan, M.K.A.; Dabravolskaj, J.; Maunula, L.; Ohinmaa, A.; Veugelers, P.J. Perceived Changes in Lifestyle Behaviours and in Mental Health and Wellbeing of Elementary School Children during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Canada. Public Health 2022, 202, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olive, L.S.; Sciberras, E.; Berkowitz, T.S.; Hoare, E.; Telford, R.M.; O’Neil, A.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Evans, S.; Hutchinson, D.; McGillivray, J.A.; et al. Child and Parent Physical Activity, Sleep, and Screen Time During COVID-19 and Associations With Mental Health: Implications for Future Psycho-Cardiological Disease? Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 774858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lunsford-Avery, J.R.; Bidopia, T.; Jackson, L.; Sloan, J.S. Behavioral Treatment of Insomnia and Sleep Disturbances in School-Aged Children and Adolescents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 30, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-89042-575-6. [Google Scholar]

- Könen, T.; Dirk, J.; Leonhardt, A.; Schmiedek, F. The Interplay between Sleep Behavior and Affect in Elementary School Children’s Daily Life. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2016, 150, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uccella, S.; Cordani, R.; Salfi, F.; Gorgoni, M.; Scarpelli, S.; Gemignani, A.; Geoffroy, P.A.; De Gennaro, L.; Palagini, L.; Ferrara, M.; et al. Sleep Deprivation and Insomnia in Adolescence: Implications for Mental Health. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blok, E.; Koopman-Verhoeff, M.E.; Dickstein, D.P.; Saletin, J.; Luik, A.I.; Rijlaarsdam, J.; Hillegers, M.; Kocevska, D.; White, T.; Tiemeier, H. Sleep and Mental Health in Childhood: A Multi-Method Study in the General Pediatric Population. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, R.; Xu, J.; Luo, Y.; Mastrotheodoros, S.; Jiang, C.; Garofalo, C.; Mazzeschi, C.; Nielsen, T.; Fong, D.Y.T.; Dzierzewski, J.M.; et al. Perceived Stress Mediates the Longitudinal Effect of Sleep Quality on Internalizing Symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 373, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, Z.; Huffman, L.G.; Oshri, A. Sleep Mediates the Effect of Stressful Environments on Youth Development of Impulsivity: The Moderating Role of within Default Mode Network Resting-State Functional Connectivity. Sleep Health 2023, 9, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cellini, N.; Di Giorgio, E.; Mioni, G.; Di Riso, D. Sleep and Psychological Difficulties in Italian School-Age Children During COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myhr, A.; Naper, L.R.; Samarawickrema, I.; Vesterbekkmo, R.K. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown on Mental Well-Being of Norwegian Adolescents During the First Wave—Socioeconomic Position and Gender Differences. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 717747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, D. Impact of Child and Family Factors on Caregivers’ Mental Health and Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece. Children 2023, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. Mental Health Commission of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2025. Available online: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Bond, L.; Butler, H.; Thomas, L.; Carlin, J.; Glover, S.; Bowes, G.; Patton, G. Social and School Connectedness in Early Secondary School as Predictors of Late Teenage Substance Use, Mental Health, and Academic Outcomes. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 40, 357.E9–357.E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cost, K.T.; Crosbie, J.; Anagnostou, E.; Birken, C.S.; Charach, A.; Monga, S.; Kelley, E.; Nicolson, R.; Maguire, J.L.; Burton, C.L.; et al. Mostly Worse, Occasionally Better: Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Canadian Children and Adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.M.; Cadigan, J.M.; Rhew, I.C. Increases in Loneliness Among Young Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Association With Increases in Mental Health Problems. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 714–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Jia, X.; Shi, H.; Niu, J.; Yin, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, X. Prevalence of Mental Health Problems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 281, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, M.; Hope, H.F.; Kolade, A.; Gellatly, J.; Osam, C.S.; Perchard, R.; Kosidou, K.; Dalman, C.; Morgan, V.; Di Prinzio, P.; et al. Effects of Parental Mental Illness on Children’s Physical Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 217, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmbach, D.A.; Anderson, J.R.; Drake, C.L. The Impact of Stress on Sleep: Pathogenic Sleep Reactivity as a Vulnerability to Insomnia and Circadian Disorders. J. Sleep Res. 2018, 27, e12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lollies, F.; Schnatschmidt, M.; Bihlmeier, I.; Genuneit, J.; In-Albnon, T.; Holtmann, M.; Legenbauer, T.; Schlarb, A.A. Associations of Sleep and Emotion Regulation Processes in Childhood and Adolescence—A Systematic Review, Report of Methodological Challenges and Future Directions. Sleep Sci. 2022, 15, 490–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.S.M.; Ng, S.S.L. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 975936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltz, J.S.; Rogge, R.D. The Moderating Role of Parents’ Dysfunctional Sleep-Related Beliefs Among Associations Between Adolescents’ Pre-Bedtime Conflict, Sleep Quality, and Their Mental Health. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2019, 15, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deacon, S.H.; Rodriguez, L.M.; Elgendi, M.; King, F.E.; Nogueira-Arjona, R.; Sherry, S.B.; Stewart, S.H. Parenting through a Pandemic: Mental Health and Substance Use Consequences of Mandated Homeschooling. Couple Fam. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2021, 10, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendi, M.M.; Stewart, S.H.; DesRoches, D.I.; Corkum, P.; Nogueira-Arjona, R.; Deacon, S.H. Division of Labour and Parental Mental Health and Relationship Well-Being during COVID-19 Pandemic-Mandated Homeschooling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groff, L.V.M.; Elgendi, M.M.; Stewart, S.H.; Deacon, S.H. Long-Term Mandatory Homeschooling during COVID-19 Had Compounding Mental Health Effects on Parents and Children. Children 2024, 11, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. 2022. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/2210-homeschool-enrollment-doubled-canada-during-covid-19-lockdowns (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- McLean, C.P.; Wachsman, T.; Morland, L.; Norman, S.B.; Hooper, V.; Cloitre, M. The Mental Health Impact of COVID-19–Related Stressors among Treatment-seeking Trauma-exposed Veterans. J. Trauma. Stress 2022, 35, 1792–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaniuka, A.R.; Kelliher Rabon, J.; Brooks, B.D.; Sirois, F.; Kleiman, E.; Hirsch, J.K. Gratitude and Suicide Risk among College Students: Substantiating the Protective Benefits of Being Thankful. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 69, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J.; Montanaro, E.; Mennicke, A.; Ybarra, M.L. Cybervictimization in Relation to Self and Other Protection and Response Behaviors: A Cross-Sectional Look at an Age-Diverse National Sample. J. Interpers. Violence 2024, 39, 3062–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A.; Lamping, D.L.; Ploubidis, G.B. When to Use Broader Internalising and Externalising Subscales Instead of the Hypothesised Five Subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British Parents, Teachers and Children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, A.-M.; Kaukonen, P.; Salmelin, R.; Joukamaa, M.; Tamminen, T. Reliability of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire among Finnish 4–9-Year-Old Children. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2012, 66, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Wu, J.; Yu, Z.; Bair, M.J.; Kean, J.; Stump, T.; Monahan, P.O. Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety and Depression Scale: Initial Validation in Three Clinical Trials. Psychosom. Med. 2016, 78, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stallwood, E.; Elsman, E.B.M.; Monsour, A.; Baba, A.; Butcher, N.J.; Offringa, M. Measurement Properties of Patient Reported Outcome Scales: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2023, 152, e2023061489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrest, C.B.; Meltzer, L.J.; Marcus, C.L.; De La Motte, A.; Kratchman, A.; Buysse, D.J.; Pilkonis, P.A.; Becker, B.D.; Bevans, K.B. Development and Validation of the PROMIS Pediatric Sleep Disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairment Item Banks. Sleep 2018, 41, zsy054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Yu, L.; Moul, D.E.; Germain, A.; Stover, A.; Dodds, N.E.; Johnston, K.L.; Shablesky-Cade, M.A.; Pilkonis, P.A. Development and Validation of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for Sleep Disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairments. Sleep 2010, 33, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanenko, Y.P.; Poppele, R.E.; Lacquaniti, F. Motor Control Programs and Walking. Neuroscientist 2006, 12, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Atlas. 2025. Available online: https://www.worldatlas.com/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Government of Canada. World Atlas. 2025. Available online: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/maps-tools-publications/maps/atlas-canada (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Varma, P.; Conduit, R.; Junge, M.; Jackson, M.L. Examining Sleep and Mood in Parents of Children with Sleep Disturbances. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2020, 12, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wearick-Silva, L.E.; Richter, S.A.; Viola, T.W.; Nunes, M.L. Sleep Quality among Parents and Their Children during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. De Pediatr. 2022, 98, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, M.L.; Fanning, K.A.; Huynh, T.; Botto, I.; Kim, C.N. Parents’ Self-Reported Psychological Impacts of COVID-19: Associations With Parental Burnout, Child Behavior, and Income. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2021, 46, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wauters, A.; Vervoort, T.; Dhondt, K.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Morbée, S.; Waterschoot, J.; Haerynck, F.; Vandekerckhove, K.; Verhelst, H.; et al. Mental Health Outcomes Among Parents of Children With a Chronic Disease During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Parental Burn-Out. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 47, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. 24-Hour Movement Guidelines; Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2025; Available online: https://csepguidelines.ca (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Paruthi, S.; Brooks, L.J.; D’Ambrosio, C.; Hall, W.A.; Kotagal, S.; Lloyd, R.M.; Malow, B.A.; Maski, K.; Nichols, C.; Quan, S.F.; et al. Recommended Amount of Sleep for Pediatric Populations: A Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2016, 12, 785–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutil, C.; Walsh, J.J.; Featherstone, R.B.; Gunnell, K.E.; Tremblay, M.S.; Gruber, R.; Weiss, S.K.; Cote, K.A.; Sampson, M.; Chaput, J.-P. Influence of Sleep on Developing Brain Functions and Structures in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 42, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussières, E.-L.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Meilleur, A.; Mastine, T.; Hérault, E.; Chadi, N.; Montreuil, M.; Généreux, M.; Camden, C.; PRISME-COVID Team. Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 691659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArthur, B.A.; Racine, N.; McDonald, S.; Tough, S.; Madigan, S. Child and Family Factors Associated with Child Mental Health and Well-Being during COVID-19. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 32, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neculicioiu, V.S.; Colosi, I.A.; Costache, C.; Sevastre-Berghian, A.; Clichici, S. Time to Sleep?—A Review of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sleep and Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Aggarwal, S.; Madaan, P.; Saini, L.; Bhutani, M. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Sleep in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep Med. 2021, 84, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, N.; McArthur, B.A.; Cooke, J.E.; Eirich, R.; Zhu, J.; Madigan, S. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada Population and Demography Statistics. 2025. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/subjects-start/population_and_demography (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- United States Census Bureau Race. 2025. Available online: https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- O’Laughlin, K.D.; Martin, M.J.; Ferrer, E. Cross-Sectional Analysis of Longitudinal Mediation Processes. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2018, 53, 375–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical Mediation Analysis in the New Millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-West, S. The Role of Social Support as a Moderator of Housing Instability in Single Mother and Two-Parent Households. Soc. Work Res. 2019, 43, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisthler, B.; Gruenewald, P.J.; Tebben, E.; Shockley McCarthy, K.; Price Wolf, J. Understanding At-the-Moment Stress for Parents during COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Restrictions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 279, 114025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OurCare Primary Care Needs. 2025. Available online: https://www.ourcare.ca/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 38.21 (6.61) |

| Gender | |

| Man | 483 (50.26%) |

| Woman | 475 (49.43%) |

| Non-Binary | 2 (0.21%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.10%) |

| Parent ethnicity | |

| White | 707 (73.60%) |

| Asian or Arab/West Asian (e.g., Armenian, Egyptian, Iranian, Lebanese, Moroccan) a | 145 (15.09%) |

| Latin American or Black or Indigenous a | 68 (7.07%) |

| Multiracial | 32 (3.30%) |

| Other | 4 (0.42%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 5 (0.52%) |

| Highest level of education completed | |

| College or university graduate b | 726 (75.55%) |

| Less than college or university completion c | 235 (24.45%) |

| Employment status (15 January–15 February) | |

| Employed d | 770 (80.13%) |

| Unemployed e | 191 (19.87%) |

| Mean number of children living at-home (SD) | 1.89 (0.89) |

| Family income | |

| CAD 25,000 or less per year | 34 (3.54%) |

| Between CAD 26,000 and 50,000 | 113 (11.76%) |

| Between CAD 51,000 and 75,000 | 184 (19.15%) |

| Between CAD 76,000 and 100,000 | 203 (21.12%) |

| Between CAD 101,000 and 125,000 | 131 (13.63%) |

| Between CAD 126,000 and 150,000 | 127 (13.22%) |

| CAD 151,000 or more per year | 138 (14.36%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 31 (3.22%) |

| Location | |

| Canada | 805 (83.77%) |

| Atlantic Provinces f | 88 (10.93%) |

| Central Canada g | 477 (59.26%) |

| Prairie Provinces h | 169 (20.99%) |

| West Coast i | 67 (8.32%) |

| Northern Territories | 2 (0.25%) |

| Unspecified | 2 (0.25%) |

| United States | 156 (16.23%) |

| North-East a | 24 (15.38%) |

| South a | 41 (26.28%) |

| Mid-West a | 8 (5.13%) |

| West a | 83 (53.21%) |

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Mean child age in years (SD) | 8.64 (2.63) |

| Child gender | |

| Boy | 551 (57.3%) |

| Girl | 408 (42.46%) |

| Non-binary | 1 (0.10%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.10%) |

| Child ethnicity | |

| White | 687 (71.49%) |

| Asian or Arab/West Asian (e.g., Armenian, Egyptian, Iranian, Lebanese, Moroccan) a | 127 (13.21%) |

| Latin America or Black or Indigenous a | 63 (6.55%) |

| Other | 12 (1.25%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 9 (0.94%) |

| Multiracial | 63 (6.56%) |

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. COVID-19 stress | - | ||||

| 2. Child sleep problems | 0.45 *** | - | |||

| 3. Parent sleep problems | 0.21 *** | 0.38 *** | - | ||

| 4. Child mental health difficulties | 0.51 *** | 0.64 *** | 0.39 *** | - | |

| 5. Parent mental health difficulties | 0.40 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.58 *** | - |

| Mean | 3.80 | 12.75 | 10.87 | 9.03 | 10.65 |

| Standard deviation | 2.55 | 7.34 | 9.34 | 3.36 | 3.63 |

| Possible range | 0–8 | 4–20 | 4–20 | 0–40 | 0–42 |

| Observed range | 0–7 | 0–31 | 0–42 | 4–19 | 4–20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ilie, A.; Kim, A.J.; DesRoches, D.; Keys, E.; Sherry, S.B.; Stewart, S.H.; Deacon, S.H.; Corkum, P.V. COVID-19 Stress and Family Well-Being: The Role of Sleep in Mental Health Outcomes for Parents and Children. Children 2025, 12, 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080962

Ilie A, Kim AJ, DesRoches D, Keys E, Sherry SB, Stewart SH, Deacon SH, Corkum PV. COVID-19 Stress and Family Well-Being: The Role of Sleep in Mental Health Outcomes for Parents and Children. Children. 2025; 12(8):962. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080962

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlie, Alzena, Andy J. Kim, Danika DesRoches, Elizabeth Keys, Simon B. Sherry, Sherry H. Stewart, S. Hélène Deacon, and Penny V. Corkum. 2025. "COVID-19 Stress and Family Well-Being: The Role of Sleep in Mental Health Outcomes for Parents and Children" Children 12, no. 8: 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080962

APA StyleIlie, A., Kim, A. J., DesRoches, D., Keys, E., Sherry, S. B., Stewart, S. H., Deacon, S. H., & Corkum, P. V. (2025). COVID-19 Stress and Family Well-Being: The Role of Sleep in Mental Health Outcomes for Parents and Children. Children, 12(8), 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080962