Parenting Under Pressure: The Transformative Impact of PCIT on Caregiver Depression and Anxiety and Child Outcomes

Abstract

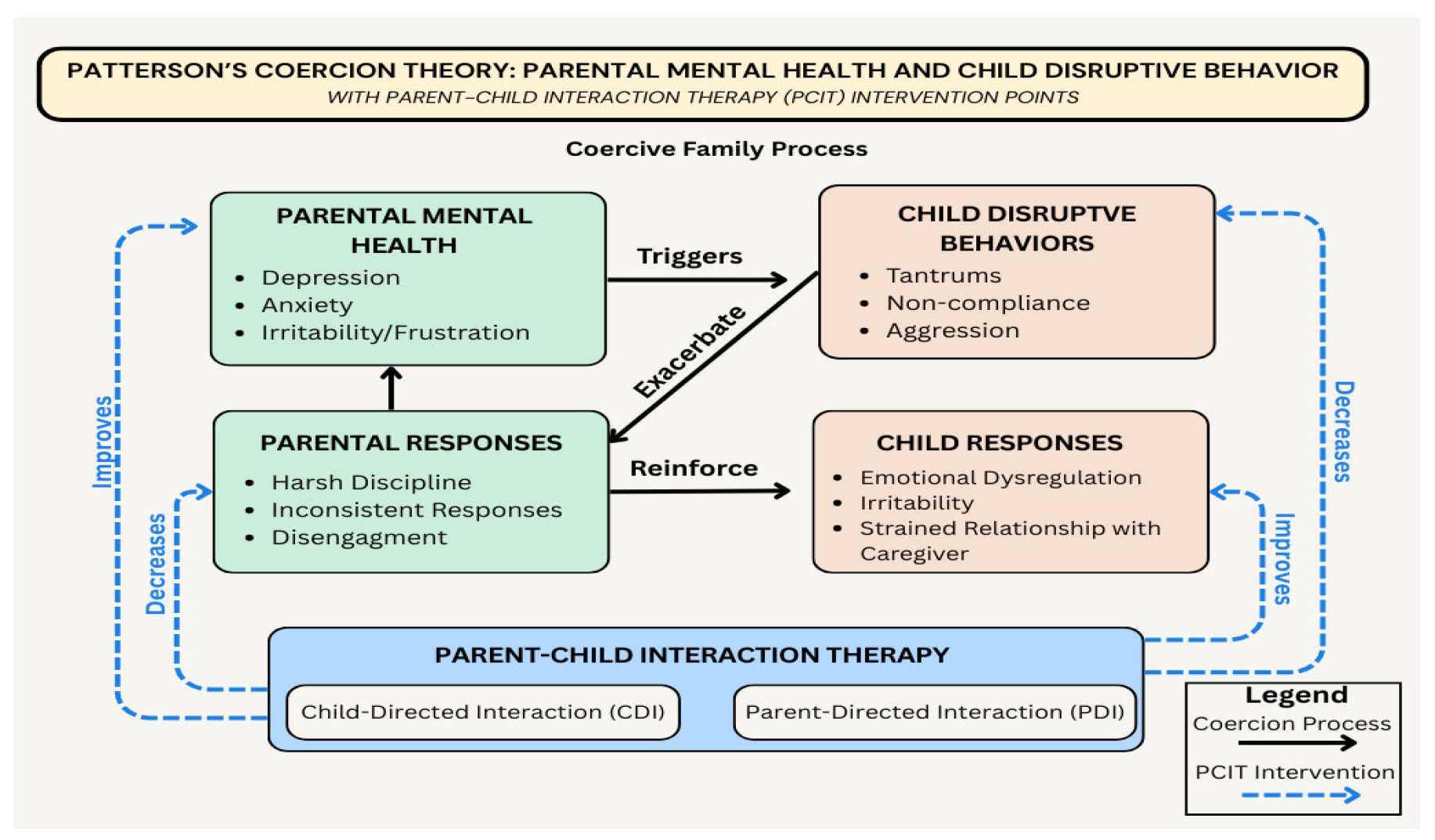

1. Introduction

1.1. Behavioral Parent Training

1.2. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

Parent–Child Interaction Therapy

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Family and Treatment Characteristics

2.3.2. Treatment Variables

2.3.3. Child Behavior Measure

2.3.4. Caregiver Skills

2.3.5. Caregiver Anxiety Symptoms

2.3.6. Caregiver Depressive Symptoms

2.4. Data Analytic Plan

2.4.1. Research Hypothesis 1 Analytic Plan

2.4.2. Research Hypothesis 2 Analytic Plan

2.4.3. Research Hypothesis 3 Analytic Plan

2.4.4. Research Hypothesis 4 Analytic Plan

2.4.5. Research Hypothesis 5 Analytic Plan

3. Results

3.1. Missing Data

3.2. Hypothesis 1: Attendance/Attrition

3.3. Hypothesis 2: Clinically Significant Changes in Family Outcomes over Time

3.3.1. Clinically Significant Caregiver Depression Changes

3.3.2. Clinically Significant Caregiver Anxiety Changes

3.3.3. Clinically Significant Child Behavior Changes

3.4. Hypothesis 3: Family Outcome Main Effects

3.4.1. Child Behavior

3.4.2. Caregiver Depression

3.4.3. Caregiver Anxiety

3.4.4. Caregiver Do/Avoid Parenting Skill Ratio

3.4.5. Caregiver Correct Follow-Through

3.5. Hypothesis 4 Moderator Analysis

3.6. Hypothesis 5 Mediation Analyses

3.6.1. Mediation Analyses for Caregiver Anxiety and Depression

3.6.2. Mediation Analysis for Child Disruptive Behavior

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPT | Behavioral Parent Training |

| PCIT | Parent–Child Interaction Therapy |

| CDI | Child-Directed Interaction |

| PDI | Parent-Directed Interaction |

| I-PCIT | Telehealth Parent–Child Interaction Therapy |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

| ECBI | Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory |

| BASC-3 | Behavior Assessment System for Children, Third Edition |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| CFI | Culture Formulation Interview |

| DPICS-IV | Dyadic Parent–Child Interaction Coding System, Fourth Version |

| CLP | Child-Led Play |

| PLP | Caregiver/Parent-Led Play |

| CU | Clean-Up |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale |

| PHQ-8 | Patient Health Questionnaire-8 |

| GEE | Generalized Estimating Equations |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

References

- Hosokawa, R.; Katura, T. Association among parents’ stress recovery experiences, parenting practices, and children’s behavioral problems: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirehag Nordh, E.-L.; Grip, K.; Axberg, U. The patient and the family: Investigating parental mental health problems, family functioning, and parent involvement in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS). Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piro-Gambetti, B.; Greenlee, J.; Hickey, E.J.; Putney, J.M.; Lorang, E.; Hartley, S.L. Parental Depression Symptoms and Internalizing Mental Health Problems in Autistic Children. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 2373–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, A.N.; Lickenbrock, D.M.; Bailes, L.G. Infant Affect Regulation with Mothers and Fathers: The Roles of Parent Mental Health and Marital Satisfaction. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2025, 34, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haine-Schlagel, R.; Dickson, K.S.; Lind, T.; Kim, J.J.; May, G.C.; Walsh, N.E.; Lazarevic, V.; Crandal, B.R.; Yeh, M. Caregiver Participation Engagement in Child Mental Health Prevention Programs: A Systematic Review. Prev. Sci. 2022, 23, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haine-Schlagel, R.; Dickson, K.S.; Shapiro, A.F.; May, G.C.; Cheng, P. Parent Mental Health Problems and Motivation as Predictors of Their Engagement in Community-Based Child Mental Health Services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 104, 104370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.R. Coercive Family Process; Castalia Publishing Company: Detroit, MI, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, G.R. Dishion, T.J., Snyder, J.J., Eds.; Coercion Theory: The Oxford Handbook of Coercive Relationship Dynamics The Study of Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, N.; Ansari, A.; Peng, P. Reconsidering the relation between parental functioning and child externalizing behaviors: A meta-analysis on child-driven effects. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snarr, J.; Slep, A.; Grande, V. Validation of a New Self-Report Measure of Parental Attributions. Psychol. Assess. 2009, 21, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agazzi, H.; Yin, T.S.; Julia, O.; Kathleen, A.; Kirby, R.S. Does Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Reduce Maternal Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Among Mothers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder? Child Fam. Behav. Ther. 2017, 39, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Z.; Maylott, S.; Rothenberg, W.; Jent, J.; Garcia, D. Parenting Stress across Time-Limited Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 3069–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, W.; Weinstein, A.; Dandes, E.; Jent, J. Improving Child Emotion Regulation: Effects of Parent–Child Interaction-therapy and Emotion Socialization Strategies. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyberg, S.M.; Funderburk, B.W. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Protocol; PCIT International: Kalispell, MT, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jent, J.; Funderburk, B.; N’zi, A.; Best, K.; Garcia, D.; Rothenberg, W.; Peskin, A.; Parlade, M.; Abner, J.P. Is perfect fidelity the enemy of good treatment? In Proceedings of the 2024 Parent Child Interaction Therapy Conference, Knoxville, TN, USA, 4–6 September 2024.

- Jent, J.F.; Rothenberg, W.A.; Peskin, A.; Acosta, J.; Weinstein, A.; Concepcion, R.; Dale, C.; Bonatakis, J.; Sobalvarro, C.; Chavez, F.; et al. An 18-week model of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: Clinical approaches, treatment formats, and predictors of success for predominantly minoritized families. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1233683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, G.E.; Sawrikar, V.; Kaouar, S.; Neo, B.; McDonogh, C.; Kimonis, E.R. The Impact of Parental Cognitions on Outcomes of Behavioral Parent Training for Children With Conduct Problems. Behav. Ther. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, B.H.; Hayes, T.; Gillenson, C.; Neuman, K.; Heymann, P.; Comer, J.S.; Bagner, D.M. Caregiver Distress and Child Behavior Problems in Children with Developmental Delay from Predominantly Minoritized Backgrounds. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2024. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, A.; Sweeting, H.; Wight, D. Parenting stress and parent support among mothers with high and low education. J. Fam. Psychol. 2015, 29, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Abell, B.; Webb, H.J.; Avdagic, E.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20170352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.M.; Hawes, T.; Swan, K.; Thomas, R.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J. Evidence-Based Treatment in Practice: PCIT Research on Addressing Individual Differences and Diversity Through the Lens of 20 Years of Service. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 2599–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comer, J.S.; Furr, J.M.; Miguel, E.M.; Cooper-Vince, C.E.; Carpenter, A.L.; Elkins, R.M.; Kerns, C.E.; Cornacchio, D.; Chou, T.; Coxe, S.; et al. Remotely delivering real-time parent training to the home: An initial randomized trial of internet-delivered parent-child interaction therapy (I-PCIT). J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peskin, A.; Barth, A.; Andrew Rothenberg, W.; Turzi, A.; Formoso, D.; Garcia, D.; Jent, J. New Therapy for a New Normal: Comparing Telehealth and in-Person Time-Limited Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Behav. Ther. 2024, 55, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyberg, S.M.; Pincus, D. Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory and Sutter-Eyberg Student Behavior Inventory: Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, C.R.; Kamphaus, R.W. Behavior Assessment System for Children, 3rd ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, A.L.; Jent, J.; Aggarwal, N.K.; Chavira, D.; Coxe, S.; Garcia, D.; La Roche, M.; Comer, J.S. Person-Centered Cultural Assessment Can Improve Child Mental Health Service Engagement and Outcomes. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2022, 51, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.; Fogg, L.; Young, M.; Ridge, A.; Cowell, J.; Sivan, A.; Richardson, R. Reliability and validity of the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory with African-American and Latino parents of young children. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Barnett, M.L.; Rothenberg, W.A.; Tonarely, N.A.; Perez, C.; Espinosa, N.; Salem, H.; Alonso, B.; San Juan, J.; Peskin, A.; et al. A Natural Helper Intervention to Address Disparities in Parent Child-Interaction Therapy: A Randomized Pilot Study. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2023, 52, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, E.M.; Schmidt, E.; Rothenberg, W.A.; Davidson, B.; Garcia, D.; Barnett, M.L.; Fernandez, C.; Jent, J.F. Universal Teacher-Child Interaction Training in early childhood special education: A cluster randomized control trial. J. Sch. Psychol. 2023, 97, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyberg, S.M.; Nelson, M.M.; Ginn, N.C.; Bhuiyan, N.; Boggs, S.R. Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS): Comprehensive Manual for Research and Training, 4th ed.; PCIT International: Kalispell, MT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg, S.M.; Nelson, M.M.; Ginn, N.C.; Bhuiyan, N.; Boggs, S.R. Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS): Clinical Manual, 4th ed.; PCIT International: Kalispell, MT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano, P.A.; Ros-Demarize, R.; Hare, M.M. Condensing parent training: A randomized trial comparing the efficacy of a briefer, more intensive version of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (I-PCIT). J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 88, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T.W.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanzer, J. Report: Average Renter in Much of U.S. Needs $100,000 Salary. 2023. Available online: https://www.fau.edu/newsdesk/articles/april2023-rental-numbers (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Montoya, A.K.; Hayes, A.F. Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychol. Methods 2017, 22, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.K. Conditional Process Analysis for Two-Instance Repeated-Measures Designs. Psychol. Methods 2024, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, S.G.; Ho, L.K.; Urquiza, A.J.; Zebell, N.M.; Fernandez, Y.G.E.; Boys, D. The effectiveness of parent-child interaction therapy with depressive mothers: The changing relationship as the agent of individual change. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2011, 42, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, E.A.; Nekkanti, A.K.; Skoranski, A.M.; Scholtes, C.M.; Lyons, E.R.; Mills, K.L.; Bard, D.; Rock, A.; Berkman, E.; Bard, E.; et al. Randomized trial of parent-child interaction therapy improves child-welfare parents’ behavior, self-regulation, and self-perceptions. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 92, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Haim, Y.; Lamy, D.; Pergamin, L.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; van IJzendoorn, M.H. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, B.; Sharma, M.; Rush, S.E.; Fournier, C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, W.A.; Anton, M.T.; Gonzalez, M.; Lafko Breslend, N.; Forehand, R.; Khavjou, O.; Jones, D.J. BPT for Early-Onset Behavior Disorders: Examining the Link Between Treatment Components and Trajectories of Child Internalizing Symptoms. Behav. Modif. 2020, 44, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.H.; Simon, H.; McCarthy, L.; Ziegler, J.; Ceballos, A. Testing Models of Associations Between Depression and Parenting Self-efficacy in Mothers: A Meta-analytic Review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 25, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, G.R.; Dishion, T.J.; Bank, L. Family interaction: A process model of deviancy training. Aggress. Behav. 1984, 10, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najman, J.M.; Williams, G.M.; Nikles, J.; Spence, S.; Bor, W.; O’Callaghan, M.; Le Brocque, R.; Andersen, M.J. Mothers’ mental illness and child behavior problems: Cause-effect association or observation bias? J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2000, 39, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringoot, A.P.; Tiemeier, H.; Jaddoe, V.W.; So, P.; Hofman, A.; Verhulst, F.C.; Jansen, P.W. Parental depression and child well-being: Young children’s self-reports helped addressing biases in parent reports. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 68, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M. The value and limitations of self-administered questionnaires in clinical practice and epidemiological studies. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Miguel, C.; Ciharova, M.; Quero, S.; Plessen, C.Y.; Ebert, D.; Harrer, M.; van Straten, A.; Karyotaki, E. Psychological treatment of depression with other comorbid mental disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2023, 52, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, C.A.; Larsson, H.; Vos, M.; Bellato, A.; Libutzki, B.; Solberg, B.S.; Chen, Q.; Du Rietz, E.; Mostert, J.C.; Kittel-Schneider, S.; et al. Anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders in adult men and women with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A substantive and methodological overview. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 151, 105209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christou, A.I.; Fanti, K.; Mavrommatis, I.; Soursou, G.; Pergantis, P.; Drigas, A. Social affiliation and attention to angry faces in children: Evidence for the contributing role of parental sensory processing sensitivity. Children 2025, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic (N = 840) | n | % | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Gender (n = 808) | ||||

| Male | 573 | 70.9 | ||

| Female | 235 | 29.1 | ||

| Language PCIT was Delivered in (n = 775) | ||||

| English | 545 | 70.3 | ||

| Spanish | 159 | 20.5 | ||

| English and Spanish | 70 | 9.0 | ||

| Portuguese | 1 | 0.1 | ||

| Caregiver Education Level (n = 804) | ||||

| Some grade school | 11 | 1.4 | ||

| High school diploma/GED | 61 | 7.6 | ||

| Some college | 86 | 10.7 | ||

| Associate degree | 58 | 7.2 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 282 | 35.1 | ||

| Graduate degree | 306 | 38.1 | ||

| Household Income (n = 762) | ||||

| Less than USD 20,000 | 62 | 8.1 | ||

| USD 20,000 to USD 34,999 | 76 | 10.0 | ||

| USD 35,000 to USD 49,999 | 74 | 9.7 | ||

| USD 50,000 to USD 74,999 | 92 | 12.1 | ||

| USD 75,000 to USD 99,999 | 106 | 13.9 | ||

| ≥ USD 100,000 | 352 | 46.2 | ||

| Child Race by Ethnicity (n = 807) | Hispanic (n = 567) | Non-Hispanic (n = 240) | ||

| White | 494 | 87.1 | 147 | 61.3 |

| Biracial or Multiracial | 47 | 8.3 | 36 | 15.0 |

| Prefer to Self-Describe | 18 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.5 |

| Black or African American | 6 | 1.1 | 42 | 17.5 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 | 0.4 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Asian | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 2.5 |

| Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.04 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PCIT Language | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2. Drop Status | 0.007 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 3. PCIT Completion | 0.043 | – | 1 | |||||||||||

| 4. # of PCIT Sessions | 0.025 | 0.728 ** | 0.752 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 5. Do Skills | 0.100 ** | 0.040 | 0.045 | 0.056 | 1 | |||||||||

| 6. Avoid Skills | 0.019 | −0.026 | −0.011 | 0.051 | 0.149 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 7. ECBI Intensity Score | −0.034 | 0.086 | −0.034 | −0.007 | −0.026 | −0.036 | 1 | |||||||

| 8. ECBI Problem Score | −0.057 | 0.111 | −0.024 | 0.024 | −0.050 | −0.059 | 0.754 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 9. Intake PHQ-8 Total Score | 0.000 | −0.028 | −0.020 | 0.041 | −0.018 | −0.042 | 0.290 ** | 0.244 ** | 1 | |||||

| 10. Intake GAD-7 Total Score | −0.019 | −0.007 | −0.001 | 0.047 | 0.031 | −0.033 | 0.255 ** | 0.211 ** | 0.715 ** | 1 | ||||

| 11. Caregiver Ethnicity | −0.355 ** | 0.027 | 0.033 | 0.092 ** | −0.064 | −0.006 | −0.036 | −0.087 * | −0.056 | −0.061 | 1 | |||

| 12. Caregiver Race | 0.138 ** | −0.053 | −0.016 | −0.003 | 0.076 * | −0.021 | 0.027 | 0.011 | 0.055 | 0.068 | −0.288 ** | 1 | ||

| 13. Child Sex | −0.003 | −0.001 | 0.029 | 0.028 | −0.017 | −0.057 | −0.057 | −0.055 | 0.006 | −0.015 | −0.032 | 0.039 | 1 | |

| 14. Child Age | −0.122 ** | −0.014 | −0.085 * | −0.112 ** | −0.290 ** | 0.300 ** | 0.048 | 0.121 ** | 0.059 | 0.022 | 0.019 | −0.026 | −0.060 | 1 |

| Outcome | Time Comparison | Mean Difference (B) | SE | 95% CI | p-Value (Bonferroni) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECBI (Child Behavior) | Pre vs. Mid | −26.73 | 1.21 | [−29.62, −23.84] | <0.001 |

| Mid vs. Post | −24.05 | 1.14 | [−26.77, −21.33] | <0.001 | |

| Pre vs. Post | −50.78 | 1.34 | [−53.98, −47.59] | <0.001 | |

| GAD-7 (Caregiver Anxiety) | Pre vs. Mid | −0.77 | 0.18 | [−1.20, −0.34] | <0.001 |

| Mid vs. Post | −1.31 | 0.18 | [−1.73, −0.89] | <0.001 | |

| Pre vs. Post | −2.08 | 0.19 | [−2.54, −1.62] | <0.001 | |

| PHQ-8 (Caregiver Depression) | Pre vs. Mid | −0.42 | 0.16 | [−0.81, −0.04] | 0.027 |

| Mid vs. Post | −0.75 | 0.15 | [−1.11, −0.40] | <0.001 | |

| Pre vs. Post | −1.17 | 0.16 | [−1.57, −0.78] | <0.001 | |

| Do/Avoid Skill Ratio | Pre vs. Mid | 4.08 | 0.26 | [3.45, 4.70] | <0.001 |

| Mid vs. Post | 1.00 | 0.34 | [0.19, 1.80] | 0.009 | |

| Pre vs. Post | 5.07 | 0.33 | [4.27, 5.87] | <0.001 | |

| Correct Follow-Through Rate | Pre vs. Post | 35.37 | 1.45 | [32.53, 38.21] | <0.001 |

| Independent Variable | B | SE | 95% CI | Wald χ2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 95.24 | 6.63 | [82.23, 108.24] | 206.17 | <0.001 |

| Time: Pre-treatment | 53.26 | 8.06 | [37.46, 69.05] | 43.67 | <0.001 |

| Time: Mid-treatment | 31.28 | 7.41 | [16.75, 45.81] | 17.80 | <0.001 |

| Parental Depression (PHQ-8) | 0.17 | 0.63 | [−1.05, 1.40] | 0.08 | 0.78 |

| Parental Anxiety (GAD-7) | 1.30 | 0.51 | [0.30, 2.30] | 6.47 | 0.01 |

| Household Income (<100K) | −2.07 | 2.81 | [−7.57, 3.44] | 0.54 | 0.46 |

| Education (Less than Bachelor’s degree) | −4.90 | 3.41 | [−11.58, 1.77] | 2.07 | 0.15 |

| Race: Asian | −5.30 | 9.53 | [−23.99, 13.38] | 0.31 | 0.58 |

| Race: Black/African American | 13.75 | 9.28 | [−4.43, 31.93] | 2.20 | 0.14 |

| Race: White | −0.47 | 6.08 | [−12.39, 11.44] | 0.01 | 0.94 |

| Race: Other | 3.11 | 10.01 | [−16.51, 22.73] | 0.31 | 0.76 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic | 0.00 | 2.85 | [−5.58, 5.59] | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Ethnicity: Haitian | −16.19 | 12.52 | [−40.73, 8.36 | 1.67 | 0.20 |

| Pre-treatment X PHQ-8 | 1.28 | 0.71 | [−0.12, 2.68] | 3.23 | 0.07 |

| Mid-treatment X PHQ-8 | 0.56 | 0.82 | [−1.05, 2.17] | 0.47 | 0.49 |

| Pre-treatment X GAD-7 | −0.73 | 0.61 | [−1.93, 0.47] | 1.43 | 0.23 |

| Mid-treatment X GAD-7 | −0.31 | 0.68 | [−1.64, 1.02] | 0.21 | 0.65 |

| Household Income (<100K) X Pre-treatment | 2.60 | 3.20 | [−3.67, 8.87] | 0.66 | 0.42 |

| Household Income (<100K) X Mid-treatment | 2.92 | 2.74 | [−2.46, 8.30] | 1.13 | 0.29 |

| Education (Less than Bachelor’s degree) X Pre-treatment | 4.18 | 3.71 | [−3.09, 11.44] | 1.27 | 0.26 |

| Education (Less than Bachelor’s degree) X Mid-treatment | −0.05 | 3.28 | [−6.49, 6.39] | 0.00 | 0.99 |

| Race: Asian X Pre-treatment | −5.31 | 10.73 | [−26.34, 15.71] | 0.25 | 0.62 |

| Race: Asian X Mid-treatment | −6.76 | 10.32 | [−26.99, 13.48] | 0.43 | 0.51 |

| Race: Black/African American X Pre-treatment | −13.43 | −13.43 | [−34.35, 7.50] | 1.582 | 0.21 |

| Race: Black/African American X Mid-treatment | −17.51 | 8.41 | [−33.99, −1.03] | 4.337 | 0.04 |

| Race: White X Pre-treatment | −11.31 | 7.41 | [−25.84, 3.22] | 2.33 | 0.13 |

| Race: White X Mid-treatment | −12.14 | 6.91 | [−25.69, 1.41] | 3.08 | 0.08 |

| Race: Other X Pre-treatment | −3.72 | 9.63 | [−22.60, 15.16] | 0.15 | 0.70 |

| Race: Other X Mid-treatment | 4.90 | 9.18 | [−13.01, 22.90] | 0.28 | 0.59 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic X Pre-treatment | 2.04 | 3.18 | [−4.20, 8.27] | 0.41 | 0.52 |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic X Mid-treatment | 0.33 | 2.59 | [−4.75, 5.41] | 0.02 | 0.90 |

| Ethnicity: Haitian X Pre-treatment | −0.84 | 15.10 | [−30.45, 28.67] | 0.00 | 0.96 |

| Ethnicity: Haitian X Mid-treatment | 7.96 | 19.72 | [−30.69, 46.61] | 0.16 | 0.69 |

| Caregiver Mental Health | Effect | Pre to Mid (B) | 95% CI Pre to Mid | Mid to Post (B) | 95% CI Mid to Post | Pre to Post (B) | 95% CI Pre to Post |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Anxiety (GAD-7) | a (Change in Caregiver Do/Avoid Ratio Skills) | 0.72 | [0.35, 1.09] | 0.65 | [0.22, 1.09] | 0.82 | [0.42, 1.23] |

| b (Change in Caregiver Do/Avoid Ratio Skills x Anxiety) | −0.81 | [−1.35, −0.27] | −0.69 | [−1.26, −0.11] | −0.94 | [−1.50, −0.34] | |

| Indirect Effect (a × b) | −0.58 | [−1.16, −0.15] | −0.45 | [−0.94, −0.06] | −0.77 | [−1.39, −0.23] | |

| Direct Effect (c’) | −0.91 | [−1.59, −0.22] | −0.78 | [−1.46, −0.12] | −1.29 | [−2.10, −0.48] | |

| Caregiver Anxiety (GAD-7) | a (Change in Caregiver Correct Follow-Through Rate) | 0.68 | [0.32, 1.03] | ||||

| b (Caregiver Correct Follow-Through Rate × Anxiety) | –0.69 | [–1.25, –0.11] | |||||

| Indirect Effect (a × b) | –0.47 | [–0.90, –0.12] | |||||

| Direct Effect (c’) | –0.92 | [–1.57, –0.28] | |||||

| Caregiver Depression (PHQ-8) | a (Change in Caregiver Do/Avoid Ratio Skills | 0.64 | [0.29, 1.01] | 0.6 | [0.20, 1.01] | 0.74 | [0.37, 1.12] |

| b (Change in Caregiver Do/Avoid Ratio Skills × Depression) | −0.81 | [−1.38, −0.27] | −0.68 | [−1.26, −0.11] | −0.91 | [−1.50, −0.34] | |

| Indirect Effect (a × b) | −0.52 | [−1.08, −0.13] | −0.41 | [−0.91, −0.04] | −0.68 | [−1.28, −0.21] | |

| Direct Effect (c’) | −1.05 | [−1.79, −0.30] | −0.89 | [−1.58, −0.18] | −1.24 | [−2.02, −0.45] | |

| Caregiver Depression (PHQ-8) | a (Change in Caregiver Correct Follow-Through Rate) | 0.69 | [0.31, 1.07] | ||||

| b (Caregiver Correct Follow-Through Rate × Anxiety) | −0.72 | [−1.31, −0.12] | |||||

| Indirect Effect (a × b) | −0.5 | [−1.09, −0.10] | |||||

| Direct Effect (c’) | −1.22 | [−2.02, −0.44] |

| Child Disruptive Behavior | Effect | Pre to Mid (B) | 95% CI Pre to Mid | Mid to Post (B) | 95% CI Mid to Post | Pre to Post (B) | 95% CI Pre to Post |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Disruptive Behavior (ECBI) | a (Change in Caregiver Do/Avoid Skill Ratio) | 4.15 | [3.61, 4.69] | 0.87 | [0.14, 1.60] | 5.02 | [4.36, 5.68] |

| b (Change in Caregiver Do/Avoid Skill Ratio × Child Disruptive Behavior) | –3.69 | [–9.10, 1.72] | −0.05 | [−0.39, 0.28] | −0.74 | [−6.86, 5.38] | |

| Indirect Effect (a × b) | –15.32 | [–39.97, 8.38] | −0.05 | [−0.38, 0.22] | −1.35 | [−15.38, 19.63] | |

| Direct Effect (c’) | –12.98 | [–35.57, 9.61] | −22.46 | [−24.91, −20.00] | −47.61 | [−63.29, −31.94] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peskin, A.; Landa, A.; Acosta, J.; Rothenberg, W.A.; Levi, R.; Davis, E.; Garcia, D.; Jent, J.F.; Mansoor, E. Parenting Under Pressure: The Transformative Impact of PCIT on Caregiver Depression and Anxiety and Child Outcomes. Children 2025, 12, 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070922

Peskin A, Landa A, Acosta J, Rothenberg WA, Levi R, Davis E, Garcia D, Jent JF, Mansoor E. Parenting Under Pressure: The Transformative Impact of PCIT on Caregiver Depression and Anxiety and Child Outcomes. Children. 2025; 12(7):922. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070922

Chicago/Turabian StylePeskin, Abigail, Alexis Landa, Juliana Acosta, William Andrew Rothenberg, Rachel Levi, Eileen Davis, Dainelys Garcia, Jason F. Jent, and Elana Mansoor. 2025. "Parenting Under Pressure: The Transformative Impact of PCIT on Caregiver Depression and Anxiety and Child Outcomes" Children 12, no. 7: 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070922

APA StylePeskin, A., Landa, A., Acosta, J., Rothenberg, W. A., Levi, R., Davis, E., Garcia, D., Jent, J. F., & Mansoor, E. (2025). Parenting Under Pressure: The Transformative Impact of PCIT on Caregiver Depression and Anxiety and Child Outcomes. Children, 12(7), 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070922