Pediatric Hematology–Oncology Provider Attitudes and Beliefs About the Use of Acupuncture for Their Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

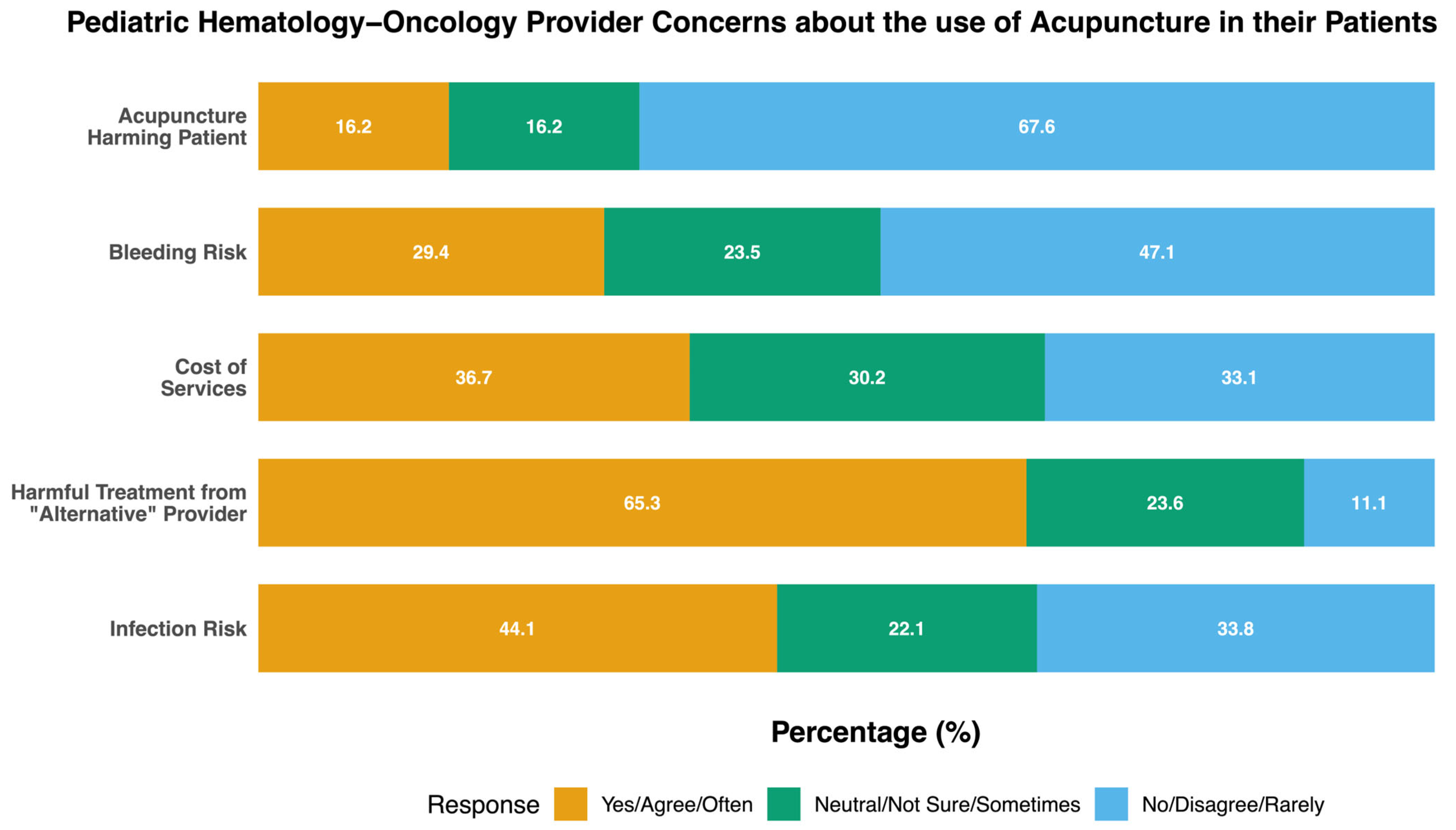

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APP | Advanced Practice Provider |

| ANC | Absolute Neutrophil Count |

| CINV | Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea/Vomiting |

| PHO | Pediatric Hematology–Oncology |

| IM | Integrative Medicine |

| IMM | Integrative Medicine Modalities |

References

- PDQ Integrative Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board. Acupuncture (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries; National Cancer Institute (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2002.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Center. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology-Survivorship-Physician Guidelines 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Mao, J.J.; Ismaila, N.; Bao, T.; Barton, D.; Ben-Arye, E.; Garland, E.L.; Greenlee, H.; Leblanc, T.; Lee, R.T.; Lopez, A.M.; et al. Integrative Medicine for Pain Management in Oncology: Society for Integrative Oncology-ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3998–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, T.; Baser, R.; Chen, C.; Weitzman, M.; Zhang, Y.L.; Seluzicki, C.; Li, Q.S.; Piulson, L.; Zhi, W.I. Health-Related Quality of Life in Cancer Survivors with Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Oncologist 2021, 26, e2070–e2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzo, J.; Vickers, A.; Richardson, M.A.; Allen, C.; Dibble, S.L.; Issell, B.; Lao, L.; Pearl, M.; Ramirez, G.; Roscoe, J.A.; et al. Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 7188–7198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Tanasijevic, A.; Kassis, S.B.; Park, S.H.; Jeong, Y.J.; Shin, I.H.; Yao, C.; Jung, H.J.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Acupuncture for hot flashes in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: A pooled analysis of individual patient data from parallel randomized trials. Cancer 2024, 130, 3219–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesi, G.; Razzini, G.; Musti, M.A.; Stivanello, E.; Petrucci, C.; Benedetti, B.; Rondini, E.; Ligabue, M.B.; Scaltriti, L.; Botti, A.; et al. Acupuncture as an integrative approach for the treatment of hot flashes in women with breast cancer: A prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial (acclimat). J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez García, E.; Nishishinya Aquino, M.B.; Cruz Martínez, O.; Ren, Y.; Xia, R.; Fei, Y.; Fernández-Jané, C. Efficacy and Safety of Acupuncture and Related Techniques in the Management of Oncological Children and Adolescent Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, D.C.; Overvåg, G.; Jong, M.C.; Kristoffersen, A.E.; Stavleu, D.C.; Liu, J.; Stub, T. Complementary and alternative medicine modalities used to treat adverse effects of anti-cancer treatment among children and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, T.M.; Benavides, M.; Emmons, S.L.; Hayes, M.; Liu, G.; Garzotto, M.; Donovan, D.; Katovic, N.; Reeder, C.; Eilers, K. Acupuncture for hot flashes in patients with prostate cancer. Urology 2010, 76, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.; Kent, P.; Swanson, B.; Rosdil, A.; Owen, E.; Fogg, L.; Keithley, J. The Use of Acupuncture for Pain Management in Pediatric Patients: A Single-Arm Feasibility Study. Altern. Complement. Ther. 2015, 21, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Perez, S.; Tung, C. Acupuncture for pediatric pain: The trend of evidence-based research. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2020, 10, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Highfield, E.S.; Laufer, M.R.; Schnyer, R.N.; Kerr, C.E.; Thomas, P.; Wayne, P.M. Adolescent endometriosis-related pelvic pain treated with acupuncture: Two case reports. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2006, 12, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.S.; Deverman, S.E.; Norvell, D.C.; Cusick, J.C.; Kendrick, A.; Koh, J. Randomized trial of acupuncture with antiemetics for reducing postoperative nausea in children. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2019, 63, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chokshi, S.K.; Ladas, E.J.; Taromina, K.; McDaniel, D.; Rooney, D.; Jin, Z.; Hsu, W.-C.; Kelly, K.M. Predictors of acupuncture use among children and adolescents with cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, M.; Lin, J.; Kim, M.; Moody, K. Pediatric oncologists’ views toward the use of complementary and alternative medicine in children with cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2009, 31, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C.D.; Meek, P.M.; Bell, I.R. Development and validation of IMAQ: Integrative Medicine Attitude Questionnaire. BMC Med. Educ. 2003, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spraker-Perlman, H.L.; Gomez-Martinez, A.; Heidelberg, R.E.; Wright, R.; Ly, A.; Meyer, M.; Taylor, H.; Zeng, E.; Mothi, S.S.; Baker, J.N.; et al. If you build it, will they come? pediatric integrative medicine service utilization in a comprehensive cancer center. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2025, 23, e257021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ast, A.; Meyer, M.; Heidelberg, R.E.; Allen, J.M.; Ly, A.; Spraker-Perlman, H. Development of a pediatric integrative oncology program: Pearls, barriers, and future directions. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 2021, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, K.; D’aMico, S.; Luo, M.; Sommers, E.; Goldstein, L.; Neri, C.; Gardiner, P. A cross-sectional review of the prevalence of integrative medicine in pediatric pain clinics across the United States. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 38, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Valois, B.; Young, T.; Zollman, C.; Appleyard, I.; Ben-Arye, E.; Cummings, M.; Green, R.; Hoffman, C.; Lacey, J.; Moir, F.; et al. Acupuncture in cancer care: Recommendations for safe practice (peer-reviewed expert opinion). Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filshie, J.; Hester, J. Guidelines for providing acupuncture treatment for cancer patients--a peer-reviewed sample policy document. Acupunct. Med. 2006, 24, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, F.Z.; Olaku, O.; Bao, T.; Berger, A.; Deng, G.; Fan, A.Y.; Garcia, M.K.; Herman, P.M.; Kaptchuk, T.J.; Ladas, E.J.; et al. The national cancer institute’s conference on acupuncture for symptom management in oncology: State of the science, evidence, and research gaps. J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. Monographs 2017, 2017, lgx005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Rosenthal, D.S. Recent advances in oncology acupuncture and safety considerations in practice. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2010, 11, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalf, R.A.; Nahirniak, S.; Guyatt, G.; Bathla, A.; White, S.K.; Al-Riyami, A.Z.; Jug, R.C.; La Rocca, U.; Callum, J.L.; Cohn, C.S.; et al. Platelet transfusion: 2025 AABB and ICTMG international clinical practice guidelines. JAMA, 2025; new online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayo, T.; Mitsuma, T.; Suzuki, M.; Ikeda, S.; Sukegawa, M.; Tsunoda, S.; Ohta, M. Bleeding Risk of Acupuncture for Patients with Hematological Malignancies Accompanying Thrombocytopenia: A Retrospective Chart Review. J. Integr. Complement. Med. 2024, 30, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladas, E.J.; Rooney, D.; Taromina, K.; Ndao, D.H.; Kelly, K.M. The safety of acupuncture in children and adolescents with cancer therapy-related thrombocytopenia. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 1487–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, C.M.; Pach, D.; Brinkhaus, B.; Wruck, K.; Tag, B.; Mank, S.; Willich, S.N. Safety of acupuncture: Results of a prospective observational study with 229,230 patients and introduction of a medical information and consent form. Forsch. Komplementmed. 2009, 16, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, K.J.; Sarah, R.; Silver-Highfield, E.; Xiarhos, E.; Barnes, L.; Berde, C. On pins and needles? Pediatric pain patients’ experience with acupuncture. Pediatrics 2000, 105, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, K.; Cohen, M. Ethics meet complementary and alternative medicine: New light on old principles. Contemp. Pediatr. 2004, 21, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Morey, S.S. NIH issues consensus statement on acupuncture. Am. Fam. Physician 1998, 57, 2545–2546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barnhart, B.J.; Reddy, S.G.; Arnold, G.K. Remind Me Again: Physician Response to Web Surveys: The Effect of Email Reminders Across 11 Opinion Survey Efforts at the American Board of Internal Medicine from 2017 to 2019. Eval. Health. Prof. 2021, 44, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C.C.; Lee, S.J.C.; Geiger, A.M.; Cox, J.V.; Ahn, C.; Nair, R.; Gerber, D.E.; Halm, E.A.; McCallister, K.; Skinner, C.S. A randomized trial of mail and email recruitment strategies for a physician survey on clinical trial accrual. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n = 78 | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Occupation | Attending | 38 (48.7) |

| Fellow | 7 (9.0) | |

| Nurse Practitioner | 28 (35.9) | |

| Physician Assistant | 2 (2.6) | |

| Nurse Anesthetist | 3 (3.8) | |

| Clinical time | 1–25% | 6 (7.7) |

| 26–50% | 14 (17.9) | |

| 51–75% | 18 (23.1) | |

| 76–100% | 40 (51.3) | |

| Years in PHO practice | 1–5 years | 25 (32.1) |

| 6–10 years | 14 (17.9) | |

| 11–15 years | 11 (14.1) | |

| 16–20 years | 11 (14.1) | |

| >20 years | 13 (16.7) | |

| Missing | 4 (5.1) | |

| Age (years) | Median (Q1–Q3) | 41 (36–53) |

| Gender | Male | 23 (29.5) |

| Female | 53 (67.9) | |

| Missing | 2 (2.6) | |

| Race | White | 64 (82.1) |

| Black | 2 (2.5) | |

| Asian | 8 (10.3) | |

| Other | 1 (1.3) | |

| Missing | 3 (3.8) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latinx | 3 (3.8) |

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 71 (91.1) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (5.1) | |

| Religion | Protestant Christian | 36 (46.2) |

| Roman Catholic | 14 (17.9) | |

| Atheist or Agnostic | 9 (11.5) | |

| None/Missing | 12 (15.3) | |

| Other * | 7 (9.1) | |

| Spirituality | Not Spiritual | 5 (6.4) |

| Slightly Spiritual | 15 (19.2) | |

| Moderately Spiritual | 28 (36.0) | |

| Very Spiritual | 27 (34.6) | |

| Missing | 3 (3.8) |

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Effects of complementary therapies are usually the result of the placebo effect (n = 72) * | Strongly agree | 1 (1.4) |

| Agree | 6 (8.3) | |

| Neutral | 28 (38.9) | |

| Disagree | 35 (48.6) | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 (2.8) | |

| Strong patient–provider relationship leads to improved outcomes (n = 72) * | Strongly agree | 42 (58.3) |

| Agree | 25 (34.7) | |

| Neutral | 4 (5.6) | |

| Disagree | 1 (1.4) | |

| Strongly disagree | 0 | |

| A patient’s innate healing capacity often determines the outcome regardless of treatment choices | Strongly agree | 10 (14.1) |

| (n = 71) * | Agree | 21 (29.6) |

| Neutral | 26 (36.6) | |

| Disagree | 10 (14.1) | |

| Strongly disagree | 4 (5.6) | |

| Physicians with knowledge of multiple medical systems (Eastern + Western) have improved patient satisfaction (n = 71) * | Strongly agree | 7 (9.9) |

| Agree | 36 (50.7) | |

| Neutral | 25 (35.2) | |

| Disagree | 2 (2.8) | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (1.4) | |

| Acupuncture is safe for PHO patients with platelet counts >20,000 (n = 69) * | Strongly agree | 10 (14.5) |

| Agree | 26 (37.7) | |

| Neutral | 29 (42.0) | |

| Disagree | 3 (4.3) | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (1.4) | |

| Acupuncture for PHO patients with ANC > 500 is safe (n = 68) * | Strongly agree | 11 (16.2) |

| Agree | 26 (38.2) | |

| Neutral | 24 (35.3) | |

| Disagree | 5 (7.4) | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 (2.9) | |

| I think acupuncture may improve my patient’s quality of life (n = 69) * | Yes | 52 (66.7) |

| No | 2 (2.6) | |

| I’m not sure | 15 (19.2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spraker-Perlman, H.L.; Busby, K.M.; Ly, A.; Meyer, M.; Baker, J.N.; Levine, D.R. Pediatric Hematology–Oncology Provider Attitudes and Beliefs About the Use of Acupuncture for Their Patients. Children 2025, 12, 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080961

Spraker-Perlman HL, Busby KM, Ly A, Meyer M, Baker JN, Levine DR. Pediatric Hematology–Oncology Provider Attitudes and Beliefs About the Use of Acupuncture for Their Patients. Children. 2025; 12(8):961. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080961

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpraker-Perlman, Holly L., Kenneth M. Busby, Amy Ly, Maggi Meyer, Justin N. Baker, and Deena R. Levine. 2025. "Pediatric Hematology–Oncology Provider Attitudes and Beliefs About the Use of Acupuncture for Their Patients" Children 12, no. 8: 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080961

APA StyleSpraker-Perlman, H. L., Busby, K. M., Ly, A., Meyer, M., Baker, J. N., & Levine, D. R. (2025). Pediatric Hematology–Oncology Provider Attitudes and Beliefs About the Use of Acupuncture for Their Patients. Children, 12(8), 961. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12080961