Parental Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Toward Cariogenic Potential of Pediatric Oral Medications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

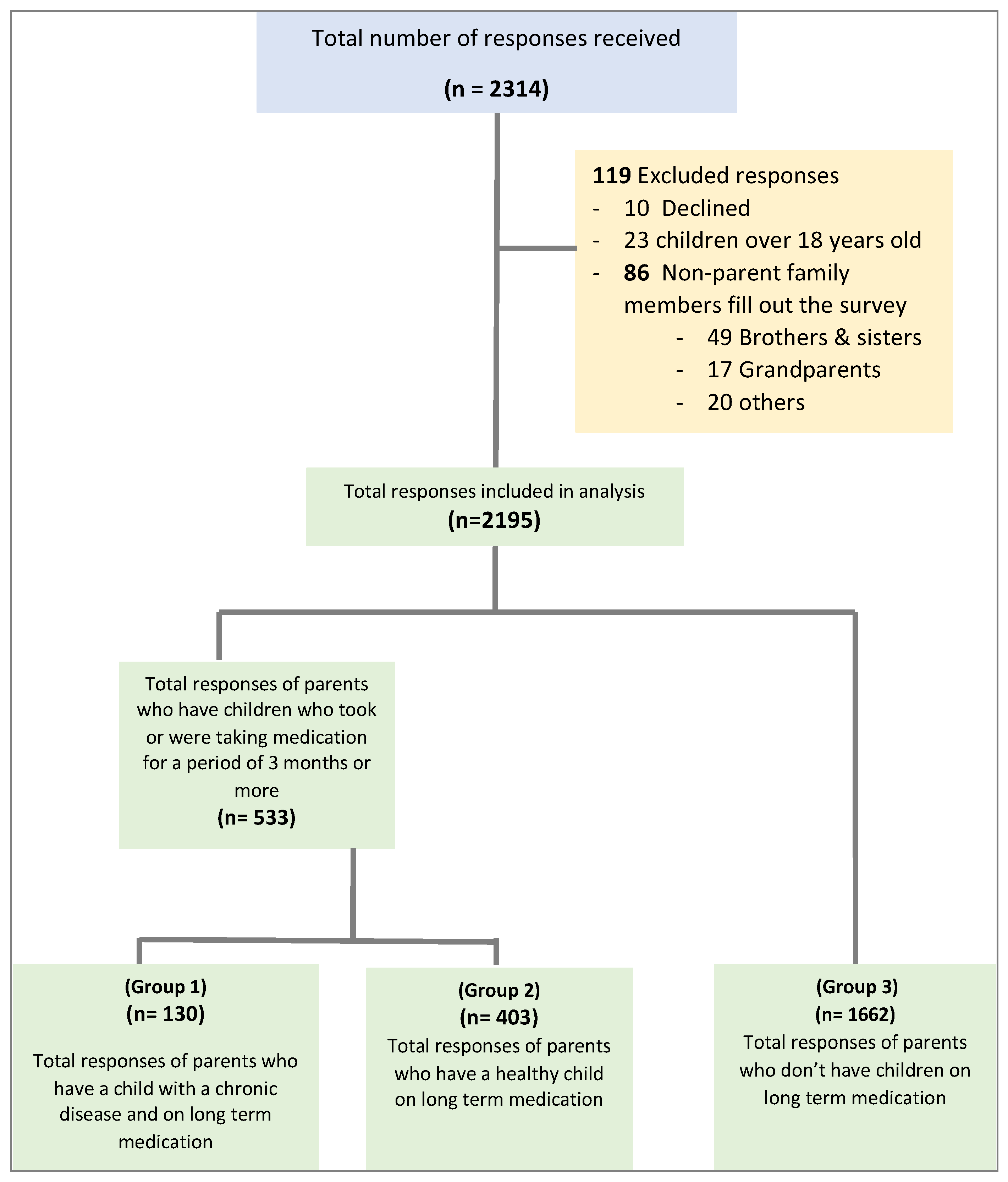

2.2. Participants and Sampling Methods

2.3. The Questionnaire

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| POMs | Pediatric oral medications |

| KAP | Knowledge, attitude and practices |

| CVI | Content Validity Index |

| CI | Confidence intervals |

| OR | Odds ratios |

Appendix A

| Dear parent, | ||||||||

| We’d like to invite you to take part in our online survey, which aims to evaluate parents’ awareness, attitudes, and behaviors regarding pediatric oral medications and their potential to cause tooth decay in Saudi Arabia. | ||||||||

| This study is being conducted by a pediatric master’s student in the Department of Pediatric Dentistry under the supervision of a research team at the faculty of Dentistry, King Abdulaziz University. | ||||||||

| Please fill out the questionnaire if your children are between 2 and 18 years old. | ||||||||

| The survey will take 6–8 min. All survey information will be kept strictly confidential and will only be seen by the research team and will only be used for research purposes. | ||||||||

| Your participation in this research is voluntary and will serve the community to increase awareness in the future. | ||||||||

| The principal investigator, | ||||||||

| Department of Pediatric Dentistry | ||||||||

| King Abdulaziz University | ||||||||

| Consent Page: | ||||||||

| Did you read and understood the part about participants’ information in the current study? | ||||||||

| Yes | ||||||||

| No | ||||||||

| Do you know that you participation is voluntary and that you are free to decline at any time? | ||||||||

| Yes | ||||||||

| No | ||||||||

| Do you agree to participate in this survey? | ||||||||

| Yes | ||||||||

| No | ||||||||

| General information about the family: | ||||||||

| Q1: What is the marital status of the child’s parents? | ||||||||

| Married | Divorced | Widowed | Deceased | |||||

| Mother’s marital status | ||||||||

| Father’s marital status | ||||||||

| Q2: What are the ages of the child’s parents? | ||||||||

| <30 years | 31–40 years | 41–50 years | >50 years | |||||

| Mother’s age | ||||||||

| Father’s age | ||||||||

| Q3: What is the educational level of the child’s parents? | ||||||||

| <High school | High school | Diploma or University | Master/PhD | |||||

| Mother’s educational level | ||||||||

| Father’s educational level | ||||||||

| Q4: What is the profession of the mother? | ||||||||

| (If the options do not apply, please write the exact position in the (other) field) | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q5: What is the profession of the mother? | ||||||||

| (If the options do not apply, please write the exact position in the (other) field) | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q6: How many children are in the family (18 or younger)? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q7: With whom does the child live? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q8: What is the monthly household income? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q9: What kind of housing do you live in? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q10: What is the region that you live in? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Knowledge, Attitude and Practices: | ||||||||

| In this section, we would like to explore the extent of your knowledge, attitude, and practices towards children’s oral medications in their various forms (syrup-chewable-pills-inhaler) and their impact on oral and dental health | ||||||||

| Q11: Children’s oral medications or some of them contain sugar flavorings. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| If the participant chooses (True) will be directed to this following question, | ||||||||

| Q11a: Which forms of the following oral medications may contain sugar flavorings? (Please select all possible options) | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q12: Do some children’s oral medications increase the possibility of tooth decay? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q13: Do some children’s oral medications lead to tooth erosion? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q14: The aim of adding sugary flavorings in oral medications is to improve the health of the child? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q15: Some children’s oral medications lead to dry mouth. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| If the participant chooses (True) will be directed to this following question, | ||||||||

| Q15a: Which forms of the following oral medications may lead to dry mouth? | ||||||||

| (Please select all possible options) | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q16: I think it is important to preserve the baby’s milk teeth. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q17: I think that decay of the baby’s teeth may affect permanent teeth. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q18: I think it is important to brush the teeth daily | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q19: What do you usually ask your child/children to do after taking an oral medication? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| If the participant chooses (Drinking water, rinsing their mouth) will be directed to this following question, | ||||||||

| Q19a: If your child rinses/drinks some water after taking oral medications, please state the reason | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q20: It is important for your child to drink water or rinse his or her mouth after taking an oral medication. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q21: Do you take your children to the dentist on a regular basis, at least once or twice a year? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q22: Do your children brush their teeth twice a day on a regular basis? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q23: Daily brushing of teeth is done with water only | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q24: Do you read the ingredients on the outside packet or the attached sheet inside the box before using any medications? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q25: Do you have any children who used to take drugs by mouth for at least 3 months, whether on prescription or without a prescription (for example, vitamins)? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| If the answer is (yes), move on to the next section | ||||||||

| Questions for healthy children on long term medications or medically compromised on long term medications | ||||||||

| Please choose one child from the family who is between the ages of 2 and 12 years old and has been taking any type of oral medication or vitamin for at least 3 months and answer the following questions: | ||||||||

| Q26: What is the child’s order in the family? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q27: Does the child suffer from any chronic diseases? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q28: What kind of medications does your child take? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q29: Your child is usually given medications | ||||||||

| Once | Twice | Three times | 4 or more | When needed | ||||

| When needed | ||||||||

| Daily | ||||||||

| Weekly | ||||||||

| Monthly | ||||||||

| Q30: How long has the child been taking/has been taking the medication? | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Q31: When time of the day does your child take his/her medications? | ||||||||

| (You can choose more than one answer) | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| This questionnaire has been filled out by: | ||||||||

| ||||||||

References

- Orfali, S.M.; Alrumikhan, A.S.; Assal, N.A.; Alrusayes, A.M.; Natto, Z.S. Prevalence and severity of dental caries in school children in Saudi Arabia: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Saudi Dent. J. 2023, 35, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Featherstone, J.D. Dental caries: A dynamic disease process. Aust. Dent. J. 2008, 53, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anantharaj, A.; Prasanna, P.; Shankarappa, P.R.; Rai, A.; Thakur, S.S.; Malge, R. An assessment of parental knowledge and practices related to pediatric liquid medications and its impact on oral health status of their children. SRM J. Res. Dent. Sci. 2014, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.L.; Ernest, T.B.; Tuleu, C.; Gul, M.O. Formulation approaches to pediatric oral drug delivery: Benefits and limitations of current platforms. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015, 12, 1727–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Humaid, J. Sweetener content and cariogenic potential of pediatric oral medications: A literature. Int. J. Health Sci. 2018, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, A.; Malarvizhi, D.; Pearlin Mary, N.S.G.; Tamilselvi, R. Influences of Sweetened Medication and Dental Caries: A Review. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 2806–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, V.; Mameli, C.; Zuccotti, G.V. Paediatric pharmacology: Remember the excipients. Pharmacol. Res. 2011, 63, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shkembi, B.; Huppertz, T. Impact of Dairy Products and Plant-Based Alternatives on Dental Health: Food Matrix Effects. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, I.A.; Sampaio, F.C.; Martínez, C.R.; Freitas, C.H.S.d.M. Sucrose concentration and pH in liquid oral pediatric medicines of long-term use for children. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2010, 27, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singana, T.; Suma, N.K. An In Vitro Assessment of Cariogenic and Erosive Potential of Pediatric Liquid Medicaments on Primary Teeth: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2020, 13, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierro, V.S.; Abdelnur, J.P.; Maia, L.C.; Trugo, L.C. Free sugar concentration and pH of paediatric medicines in Brazil. Community Dent. Health 2005, 22, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goyal, A.; Rani, V.; Manjunath, B.C.; Rathore, K. Relationship between pediatric liquid medicines (PLMs) and dental caries in chronically ill children. Padjadjaran J. Dent. 2019, 31, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandary, S.; Pooja, M.; Shetty, U.A. Paediatricians Perceptions towards the Use of Sweetened Liquid Medications and its Relationship to Oral Health of Children. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2019, 8, 3070–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A.N.; Pradhan, N.; Poonacha, K.; Dave, B.; Raol, R.; Jain, A. Evaluation of erosive and cariogenic potential of pediatric liquid formulated drugs commonly prescribed in India: A physiochemical study. J. Datta Meghe Inst. Med. Sci. Univ. 2021, 16, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Panda, S. Cariogenic Potential of the commonly Prescribed Pediatric Liquid Medicaments in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An in vitro Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2017, 18, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, E.H.; Jun, M.K. Evaluation of the Erosive and Cariogenic Potential of Over-the-Counter Pediatric Liquid Analgesics and Antipyretics. Children 2021, 8, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukundan, D.; R, V. Comparative Evaluation on the Effects of Three Pediatric Syrups on Microhardness, Roughness and Staining of the Primary Teeth Enamel: An In-Vitro Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e42764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peker, O.; Arıkan, R. Dental Erosion in Primary Teeth. Uşak Üniversitesi Diş Hekim. Fakültesi Derg. 2023, 2, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Thie, N.M.; Kato, T.; Bader, G.; Montplaisir, J.Y.; Lavigne, G.J. The significance of saliva during sleep and the relevance of oromotor movements. Sleep Med. Rev. 2002, 6, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Menezes, V.A.; Cavalcanti, G.; Mora, C.; Garcia, A.F.G.; Leal, R.B. Pediatric medicines and their relationship to dental caries. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 46, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmala, S.; Popuri, V.D.; Chilamakuri, S.; Nuvvula, S.; Veluru, S.; Babu, M.M. Oral health concerns with sweetened medicaments: Pediatricians’ acuity. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamanzadeh, V.; Ghahramanian, A.; Rassouli, M.; Abbaszadeh, A.; Alavi-Majd, H.; Nikanfar, A.-R. Design and implementation content validity study: Development of an instrument for measuring patient-centered communication. J. Caring Sci. 2015, 4, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, M.G.; Gurunathan, D. Evaluation of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Pediatricians Towards Long-Term Liquid Medicaments and its Association with Dental Health. J. Educ. Teach. Train. 2023, 13, 491–496. [Google Scholar]

- Thosar, N.R.; Bane, S.P.; Hake, N.; Gupta, S.; Baliga, S.; Rathi, N. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Mothers for Administration of Medicaments to Their Children and its Correlation with Dental Caries. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev. 2020, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinanoff, N.; Palmer, C.A. Dietary determinants of dental caries and dietary recommendations for preschool children. J. Public Health Dent. 2000, 60, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lussi, A.; Megert, B.; Shellis, R.P. The erosive effect of various drinks, foods, stimulants, medications and mouthwashes on human tooth enamel. Swiss Dent. J. 2023, 133, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, K.; Lam, P.P.Y.; Yiu, C.K.Y. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Erosive Tooth Wear among Preschool Children-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eymirli, P.S.; Öztürk, Ş.; Karahan, S.; Turgut, M.D.; Tekçiçek, M.U. The Effect of Label and Medication Package Insert Reading Habits of Parents on their Children’s Oral Dental Health. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 45, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.H.; Naseem, M.; Khan, M.S.; Asiri, F.Y.; AlQarni, I.; Gulzar, S.; Nagarajappa, R. Oral health knowledge and attitude among caregivers of special needs patients at a Comprehensive Rehabilitation Centre: An analytical study. Ann. Stomatol. 2017, 8, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmarais, A.V.; Kevill, K.; Glick, A.F. The Complex Impact of Health Literacy Among Parents of Children With Medical Complexity. Hosp. Pediatr. 2024, 14, e449–e451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinchalkar, R.P.; Yadav, S.K. Influence of Maternal Oral Health Knowledge and Practices on the Child’s Oral Health. J. Mahatma Gandhi Univ. Med. Sci. Technol. 2021, 4, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, A.B.V.D.; Bergo, B.R.; Rodrigues, R.; Oliveira, J.D.S.D.; Fernandes, L.A.; Gomes, H.D.S.; de Lima, D.C.D. Maternal Education Level as a Risk Factor for Early Childhood Caries. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clínica Integr. 2024, 24, e220138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Responses | Group 1 (n = 130) | Group 2 (n = 403) | Group 3 (n = 1662) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother age | ≤30 years | 15 (11.5) | 112 (27.8) | 383 (23.0) | <0.001 * |

| 31–40 years | 63 (48.5) | 213 (52.9) | 884 (53.2) | ||

| 41 years or more | 52 (40.0) | 78 (19.4) | 395 (23.8) | ||

| Father age | ≤40 years | 63 (48.5) | 261 (64.8) | 898 (54.0) | <0.001 * |

| 41 years or more | 67 (51.5) | 142 (35.2) | 764 (46.0) | ||

| Mother education | High school or less | 30 (23.1) | 47 (11.7) | 312 (18.8) | <0.001 * |

| Diploma or University | 69 (53.1) | 235 (58.3) | 992 (59.7) | ||

| Higher Education | 31 (23.8) | 121 (30.0) | 358 (21.5) | ||

| Father education | High school or less | 35 (26.9) | 48 (11.9) | 366 (22.0) | <0.001 * |

| Diploma or University | 63 (48.5) | 245 (60.8) | 884 (53.2) | ||

| Higher Education | 32 (24.6) | 110 (27.3) | 412 (24.8) | ||

| Job status of the mother | Employed | 46 (35.4) | 159 (39.5) | 628 (37.8) | 0.066 |

| Owns a business | 12 (9.2) | 25 (6.2) | 83 (5.0) | ||

| Housewife/ unemployed | 69 (53.1) | 207 (51.4) | 888 (53.4) | ||

| Retired | 2 (1.5) | 3 (0.7) | 45 (2.7) | ||

| Other (mainly students) | 1 (0.8) | 9 (2.2) | 18 (1.1) | ||

| Job status of the father | Employed | 88 (67.7) | 318 (78.9) | 1257 (75.6) | 0.460 |

| Owns a business | 24 (18.5) | 51 (12.7) | 249 (15.0) | ||

| Unemployed | 13 (10.0) | 24 (6.0) | 118 (7.1) | ||

| Retired | 4 (3.1) | 8 (2.0) | 29 (1.7) | ||

| Other (mainly students) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | 9 (0.5) | ||

| Monthly household income | <10,000 SAR | 50 (38.5) | 154 (38.2) | 604 (36.3) | 0.013 * |

| 10,001–20,000 SAR | 39 (30.0) | 140 (34.7) | 682 (41.0) | ||

| >20,000 SAR | 41 (31.5) | 109 (27.0) | 376 (22.6) | ||

| Housing | Rented apartment | 48 (36.9) | 174 (43.2) | 690 (41.5) | 0.058 |

| Owned apartment | 25 (19.2) | 101 (25.1) | 467 (28.1) | ||

| Rented house | 10 (7.7) | 19 (4.7) | 62 (3.7) | ||

| Owned house | 41 (31.5) | 94 (23.3) | 396 (23.8) | ||

| Others | 6 (4.6) | 15 (3.7) | 47 (2.8) | ||

| The number of children less than 18 years in the house | 1 | 18 (13.8) | 90 (22.3) | 329 (19.8) | <0.001 * |

| 2–3 | 71 (54.6) | 255 (63.3) | 1020 (61.4) | ||

| 4 or more | 41 (31.5) | 58 (14.4) | 313 (18.8) |

| Questions | Responses | Group 1 (n = 130) | Group 2 (n = 403) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What kind of medications your child uses? (You can choose more than one answer) | Syrup | 68 (52.3) | 271 (67.6) | 0.002 * |

| Tablets | 45 (34.6) | 42 (10.5) | <0.001 * | |

| Chewing | 22 (16.9) | 132 (32.9) | <0.001 * | |

| Inhaler | 43 (33.1) | 37 (9.2) | <0.001 * | |

| Other | 8 (6.2) | 19 (4.7) | 0.523 | |

| For how long did the child take the medicine? | 3–6 months | 38 (29.2) | 299 (74.2) | <0.001 * |

| 6–12 months | 7 (5.4) | 29 (7.2) | ||

| >12 months | 85 (65.4) | 75 (18.6) | ||

| How frequent is your child given medications? | When needed | 34 (26.6) | 222 (55.2) | <0.001 * |

| Daily | 90 (70.3) | 164 (40.8) | ||

| Weekly or monthly | 4 (3.1) | 16 (4.0) | ||

| When does/did the child take the medication? (You can choose more than one answer) | Morning | 64 (49.2) | 142 (35.3) | 0.005 * |

| After meals | 27 (20.8) | 182 (45.3) | <0.001 * | |

| Evening | 53 (40.8) | 87 (21.6) | <0.001 * | |

| Bedtime | 41 (31.5) | 52 (12.9) | <0.001 * | |

| Other | 9 (6.9) | 41 (10.2) | 0.266 |

| Statements | Responses | Group 1 (n = 130) | Group 2 (n = 403) | Group 3 (n = 1662) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s oral medications or some of them contain sugar flavorings | True (Correct) | 102 (78.5) | 338 (83.9) | 1339 (80.6) | 0.135 |

| False | 3 (2.3) | 7 (1.7) | 65 (3.9) | ||

| IDK | 25 (19.2) | 58 (14.4) | 528 (15.5) | ||

| Do some children’s oral medications increase the possibility of tooth decay? | Yes (Correct) | 66 (50.8) | 201 (49.9) | 766 (46.1) | 0.415 |

| No | 22 (16.9) | 54 (13.4) | 254 (15.3) | ||

| IDK | 42 (32.3) | 148 (36.7) | 642 (38.6) | ||

| Some children’s oral medications lead to dry mouth. | True (Correct) | 59 (45.4) | 155 (38.5) | 565 (34.0) | 0.046 * |

| False | 13 (10.0) | 44 (10.9) | 224 (13.5) | ||

| IDK | 58 (44.6) | 204 (50.6) | 873 (52.5) | ||

| Do some children’s oral medications lead to tooth erosion? | Yes (Correct) | 50 (38.5) | 133 (33.0) | 460 (27.7) | 0.024 * |

| No | 22 (16.9) | 63 (15.6) | 319 (19.2) | ||

| IDK | 58 (44.6) | 207 (51.4) | 883 (53.1) | ||

| I think it is important to drink water or rinse the mouth after taking an oral medication | Agree (Preferable) | 108 (83.1) | 297 (73.7) | 1194 (71.8) | 0.062 |

| Disagree | 5 (3.8) | 14 (3.5) | 76 (4.6) | ||

| IDK | 17 (13.1) | 92 (22.8) | 392 (23.6) | ||

| Usually, after giving one of your children medicines orally, you ask him/her to: | Drink water, rinse, or brush (Desirable) | 122 (93.8) | 344 (85.4) | 1425 (85.7) | 0.032 * |

| Do nothing | 8 (6.2) | 59 (14.6) | 237 (14.3) | ||

| Do you read the ingredients on the outside packet or the attached sheet inside the box before using any medications? | Yes (Desirable) | 88 (67.7) | 255 (63.3) | 960 (57.8) | 0.018 * |

| No or sometimes | 42 (32.3) | 148 (36.7) | 702 (42.2) | ||

| Overall KAP score | High | 97 (74.6) | 285 (70.7) | 1068 (64.3) | 0.005 * |

| Low | 33 (25.4) | 118 (29.3) | 594 (35.7) |

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Group 1 | 1.60 | 1.06–2.42 | 0.026 * |

| Group 2 | 1.35 | 1.06–1.72 | 0.014 * | |

| Group 3 | Reference | |||

| Mother age | ≤30 years | 1.19 | 0.83–1.71 | 0.333 |

| 31–40 years | 1.30 | 0.99–1.71 | 0.060 | |

| 41 years or more | Reference | |||

| Father age | ≤40 years | 0.76 | 0.59–0.99 | 0.039 * |

| 41 years or more | Reference | |||

| Mother education | High school or less | 0.66 | 0.48–0.91 | 0.011 * |

| Diploma or University | 0.73 | 0.57–0.922 | 0.009 * | |

| Higher Education | Reference | |||

| Father education | High school or less | 1.26 | 0.92–1.72 | 0.149 |

| Diploma or University | 0.99 | 0.78–1.24 | 0.915 | |

| Higher Education | Reference | |||

| Family income | <10,000 SAR | 0.99 | 0.76–1.31 | 0.990 |

| 10,001–20,000 SAR | 0.82 | 0.64–1.04 | 0.098 | |

| >20,000 SAR | Reference | |||

| Number of children less than 18 years | 1 | 0.82 | 0.61–1.11 | 0.191 |

| 2–3 | 1.09 | 0.85–1.40 | 0.475 | |

| 4 or more | Reference | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Amoudi, R.M.; Elkhodary, H.M.; Abudawood, S.N.; El-Housseiny, A.; Felemban, O.M. Parental Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Toward Cariogenic Potential of Pediatric Oral Medications. Children 2025, 12, 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081100

Al-Amoudi RM, Elkhodary HM, Abudawood SN, El-Housseiny A, Felemban OM. Parental Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Toward Cariogenic Potential of Pediatric Oral Medications. Children. 2025; 12(8):1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081100

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Amoudi, Reham M., Heba Mohamed Elkhodary, Shahad N. Abudawood, Azza El-Housseiny, and Osama M. Felemban. 2025. "Parental Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Toward Cariogenic Potential of Pediatric Oral Medications" Children 12, no. 8: 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081100

APA StyleAl-Amoudi, R. M., Elkhodary, H. M., Abudawood, S. N., El-Housseiny, A., & Felemban, O. M. (2025). Parental Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Toward Cariogenic Potential of Pediatric Oral Medications. Children, 12(8), 1100. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081100