Building Bridges: Developing and Implementing a New Transition to Adult Care Program for Youth with Complex Healthcare Needs at a Canadian Children’s Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Program Development

2.1.1. Environmental Scan

2.1.2. Knowledge User Engagement

2.1.3. Evaluation Plan

3. Results

3.1. Pilot Phase

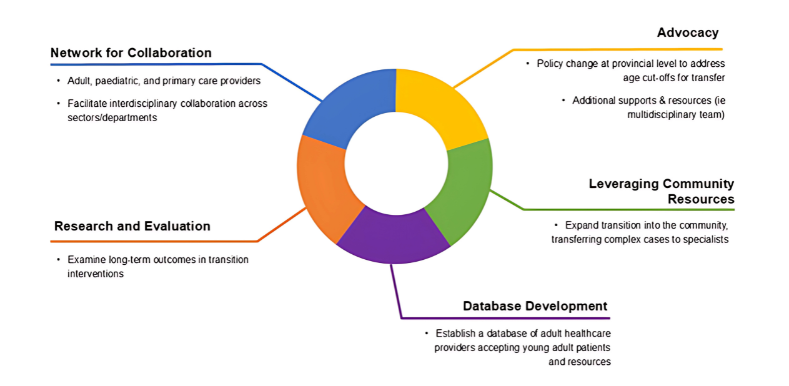

3.2. Transition to Adult Care Program Model of Care

3.3. Knowledge User Engagement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMC | Children and youth with medical complexity |

| TAC | Transition to adult care |

| PCP | Primary care provider |

| EMR | Electronic Medical Record |

References

- Blum, R.W. Introduction. Improving transition for adolescents with special health care needs from pediatric to adult-centered health care. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 1301–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toulany, A.; Gorter, J.W.; Harrison, M. A call for action: Recommendations to improve transition to adult care for youth with complex health care needs. Paediatr. Child Health 2022, 27, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, M.; Pinzon, J.; Society, C.P.; Committee, A.H. Transition to adult care for youth with special health care needs. Paediatr. Child Health 2007, 12, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, R.W.M.; Garell, D.; Hodgman, C.H.; Jorissen, T.W.; Okinow, N.A.; Orr, D.P.; Slap, G.B. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions: A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J. Adolesc. Health 1993, 14, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coming of Age: Opportunities for Investing in Adolescent Health in Canada; Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto Accessing Centre for Expertise: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020.

- National Transitions Community of Practice. A Guideline for Transition from Paediatric to Adult Health Care for Youth with Special Health Care Needs: A National Approach; Canadian Association of Pediatric Health Centres: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Health Quality Ontario. Transitions From Youth to Adult Health Care Services. 2022. Available online: https://hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/evidence/quality-standards/qs-transitions-from-youth-to-adult-health-care-services-quality-standard-en.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Li, L.; Soper, A.K.; McCauley, D.; Gorter, J.W.; Doucet, S.; Greenaway, J.; Luke, A. Landscape of healthcare transition services in Canada: A multi-method environmental scan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamater, A.M.; Guzman, A.; Aparicio, K. Mental health issues in children and adolescents with chronic illness. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2017, 10, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.N.; Schaefer, M.R.; Resmini-Rawlinson, A.; Wagoner, S.T. Barriers to Transition From Pediatric to Adult Care: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, I.; Buchan, M.C.; Ferro, M.A. Multimorbidity in children and youth: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S.; Chien, A.T.; Wisk, L.E. Mental Illness Among Youth With Chronic Physical Conditions. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20181819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, A.S.; Fournier, A.; Swan, L.; Marelli, A.J.; Kovacs, A.H. Transition and Transfer From Pediatric to Adult Congenital Heart Disease Care in Canada: Call For Strategic Implementation. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 1640–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawra, J.; Toulany, A.; Cohen, E.; Moore Hepburn, C.; Guttmann, A. Primary care interventions to improve transition of youth with chronic health conditions from paediatric to adult healthcare: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schraeder, K.; Allemang, B.; Felske, A.N.; Scott, C.M.; McBrien, K.A.; Dimitropoulos, G.; Samuel, S. Community based Primary Care for Adolescents and Young Adults Transitioning From Pediatric Specialty Care: Results from a Scoping Review. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13, 21501319221084890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, D.; Wray, J. Non-adherence and transition clinics. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 46–47, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, K.; Avolio, J.; Lo, L.; Gajaria, A.; Mooney, S.; Greer, K.; Martens, H.; Tami, P.; Pidduck, J.; Cunningham, J.; et al. Social and Structural Drivers of Health and Transition to Adult Care. Pediatrics 2024, 153, e2023062275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Berry, J.G.; Sanders, L.; Schor, E.L.; Wise, P.H. Status Complexicus? The Emergence of Pediatric Complex Care. Pediatrics 2018, 141, S202–S211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, K.; Lee, S.; de Los Reyes, T.; Lo, L.; Cleverley, K.; Pidduck, J.; Mahood, Q.; Gorter, J.W.; Toulany, A. Quality Indicators for Youth Transitioning to Adult Care: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2021055033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Collins, P.A.; Mahoney, E.; Baker, L.H. The development and testing of a measure assessing clinician beliefs about patient self-management. Health Expect 2010, 13, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, P.E.; DeChillo, N.; Friesen, B.J. Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: A brief questionnaire. Rehabil. Psychol. 1992, 37, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangione-Smith, R. Family Experiences with Care Coordination measure set (FECC). Available online: http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/policymakers/chipra/factsheets/chipra_15-p002-ef.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Larsen, D.L.; Attkisson, C.C.; Hargreaves, W.A.; Nguyen, T.D. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Eval. Program. Plan. 1979, 2, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Bronskill, S.E.; Seow, H.; Junek, M.; Feeny, D.; Costa, A.P. Associations between continuity of primary and specialty physician care and use of hospital-based care among community-dwelling older adults with complex care needs. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, A.; Balogh, R.; Lin, E.; Wilton, A.S.; Lunsky, Y. Emergency Department Use: Common Presenting Issues and Continuity of Care for Individuals With and Without Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 3542–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, D.W.; Jarvis, A.; LeBlanc, L.; Gravel, J. Revisions to the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale paediatric guidelines (PaedCTAS). Cjem 2008, 10, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, K.L.; Jembere, N.; Campitelli, M.A.; Buchan, S.A.; Chung, H.; Kwong, J.C. Using physician billing claims from the Ontario Health Insurance Plan to determine individual influenza vaccination status: An updated validation study. CMAJ Open 2016, 4, e463–e470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.S.; Stucky, B.D.; Thissen, D.; Varni, J.W.; DeWitt, E.M.; Irwin, D.E.; Yeatts, K.B.; DeWalt, D.A. Development and psychometric properties of the PROMIS(®) pediatric fatigue item banks. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 2417–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.A.; Lunsky, Y. The Brief Family Distress Scale: A Measure of Crisis in Caregivers of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2011, 20, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.S.; Kohlmann, T.; Janssen, M.F.; Buchholz, I. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: A systematic review of the literature. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 647–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Thomson, D.; Diaz, S.; Soscia, J.; Adams, S.; Amin, R.; Bernstein, S.; Blais, B.; Bruno, N.; Colapinto, K.; et al. Promoting Intensive Transitions for Children and Youth with Medical Complexity from Paediatric to Adult Care: The PITCare study—Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e086088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Quality Ontario. Quality Improvement Guide. 2012. Available online: https://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/documents/qi/qi-quality-improve-guide-2012-en.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Stinson, J.; Kohut, S.A.; Spiegel, L.; White, M.; Gill, N.; Colbourne, G.; Sigurdson, S.; Duffy, K.W.; Tucker, L.; Stringer, E.; et al. A systematic review of transition readiness and transfer satisfaction measures for adolescents with chronic illness. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2014, 26, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.A.; Daniel, L.C.; Brumley, L.D.; Barakat, L.P.; Wesley, K.M.; Tuchman, L.K. Measures of readiness to transition to adult health care for youth with chronic physical health conditions: A systematic review and recommendations for measurement testing and development. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varty, M.; Popejoy, L.L. A Systematic Review of Transition Readiness in Youth with Chronic Disease. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 42, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, K.M.; Sundaram, V.; Bravata, D.M.; Lewis, R.; Lin, N.; Kraft, S.A.; McKinnon, M.; Paguntalan, H.; Owens, D.K. Closing the quality gap: A critical analysis of quality improvement strategies. In AHRQ Technical Reviews and Summarizes; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2007; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, M.; Doucet, S.; Luke, A.; Goudreau, A.; MacNeill, L. Improving the transition from paediatric to adult healthcare: A scoping review on the recommendations of young adults with lived experience. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ontario Health Quality Standard | Outcome | Example of Measure/Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Early Identification and Transition Readiness | Transition readiness | Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire |

| Self-management | Patient Activation Measure ® [for youth] [20], Family Empowerment Survey [for caregivers] [21] | |

| Patient self-efficacy | General Self-Efficacy Scale | |

| Information Sharing and Support | Utility of care planning tools | Family Experiences With Care Coordination-16,17 [22] |

| Education and resources | Youth and/or caregiver receipt of counselling and resources on needs-based services and supports | |

| Satisfaction with transition healthcare | Larsen Client Satisfaction Questionnaire [23] | |

| Transition Plan | Co-creating a written transition plan with youth and caregiver(s) | Family Experiences With Care Coordination-18 [22] |

| Coordinated Transition | Coordination of care between and among providers and families | Family Experiences WithCare Coordination-8a,8b and 5 [22] |

| Introduction to Adult Services | Collaborative transitions meeting | Participation in a joint transitions meeting including pediatric providers, and key adult healthcare providers and the patient, and caregiver(s) |

| Transfer initiation | Time to first adult subspecialty care visit | |

| Transfer Completion | Transfer to continuous primary care | (a) Modified Bice–Boxerman Index [24] (b) Usual Provider of Care Index [25] |

| Transfer to continuous subspecialty care | Modified Bice–Boxerman Index [24] | |

| Successful transfer | Attendance of the first appointment with a primary care and/or subspecialty care provider within 6 to 12 months post-transfer | |

| Other Domains: | ||

| Use of services | Low acuity emergency department visit | Visits to the emergency department with CTAS score of 4/5 [26] |

| Emergency department use and hospitalization | Emergency Department Visits and Inpatient Days | |

| Technological complications | Gastrostomy, Tracheostomy and Ventriculoperitoneal shunts | |

| Immunization | Influenza vaccination [27] | |

| Health-related quality of life | Caregiver fatigue | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Fatigue Scale [28] |

| Family distress | Brief Family Distress Scale [29] | |

| Patient health-related quality of life and general health status 1 | Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 4.0 Generic Core Scale Teen Report | |

| Utility cost-effectiveness | Utility (youth/adult) | EuroQol 5-Dimension 5-Level [30] |

| Utility (caregiver) | EuroQol 5-Dimension 5-Level [30] | |

| Incremental cost-utility ratio | Total costs of care over study interval, patient utility gains/losses and caregiver utility gains/losses | |

| Experience with care | Overall transition experience | Qualitative interviews with youth and/or caregivers |

| Core TAC Program Activity | Description |

|---|---|

| Supporting transition readiness | Achieving transition readiness involves equipping youth and their caregiver(s) with the necessary skills to better navigate the adult healthcare system, emphasizing self-management for youth (when appropriate) to manage their health autonomously [33,34]. Central to readiness is self-efficacy, the belief in one’s ability to complete relevant activities and manage their chronic health condition(s) effectively [35]. Core principles of transition underscore the importance of routine readiness assessments and support for youths to increase their independence in managing their healthcare [2]. A comprehensive intake, focused on transition readiness and needs/risk assessment, is conducted upon acceptance into the program. Regular collaborative reviews of transition readiness are also conducted throughout to address the ongoing preparation needs of youths and their caregiver(s). The TAC program incorporates readiness preparation, self-management, and efficacy skills development into the care plan. This approach facilitates successful transitions to adult care and aims to sustain or improve health outcomes for youths with chronic health conditions. |

| Information sharing and support | Young people (and their caregiver(s), where appropriate) are offered developmentally appropriate information and support by the TAC team to meet their needs throughout the transition process. Information-sharing is collaborative, and healthcare providers actively seek the experience and expertise of the youth (and their caregivers, where appropriate) and incorporate it into the transition planning and shared goal-setting. |

| Individualized transition plan | The goal of the TAC program is to support an individualized, holistic, and coordinated transition for each patient and their caregiver (s) across multiple care settings, focused on the youth’s (and/or caregivers’) highest priority transition needs. This process includes co-developing an individualized transition plan, in collaboration with the youth and caregiver(s), to address their medical, psychosocial, and developmental needs. It also involves identifying goals and setting timelines for transition milestones. The transition plan is documented and shared within their circle of care. The clinical team oversees the refinement and maintenance of the transition plan, incorporating input from all care providers to facilitate care coordination, streamline information sharing, and consolidate multiple healthcare visits. |

| Care coordination | Care coordination is defined as the ‘deliberate organization of patient care activities between ≥2 participants to facilitate the appropriate delivery of healthcare services.’ [36] Successful transition encompasses the provision of continuous, well-coordinated care tailored to the developmental needs of a youth. The TAC team act as the youth’s designated most responsible provider for the transition process and engage in tasks including, but not limited to, care navigation, arranging and/or attending appointments, advocating for youth and families, and providing support throughout the transition process. This also includes facilitating information exchange with both medical and non-medical professionals central to the youth’s care (e.g., teachers, community home care providers). This process aims to foster collaborative care management among the youth’s care team while enhancing the confidence and capacity of both the youth and caregiver(s). |

| Connection to primary and adult care services | The TAC clinical team aims to facilitate a joint meeting with key adult providers and/or primary care before the transfer to facilitate and maintain continuity of care. This “warm handover” encourages communication among providers and active participation on the part of the youth in care decisions. Taking a proactive approach enhances the transition experience and empowers youth by recognizing their expertise in their own lives, fostering increased autonomy, independence, and confidence [37]. |

| Post-transfer support | The TAC program extends support to youth and their primary caregiver for at least 1 year beyond the age of transfer at 18 years, thereby bridging the gap between sectors and monitoring secure attachment to adult and primary care services. Activities post-transfer include, but are not limited to, creating and following up on referrals, attending visits, facilitating connections with adult services in the hospitals and community, maintaining and updating transition documents and plans, ongoing transition progress tracking and education, addressing feelings, setting expectations, and building self-management skills (where able). Whenever possible, youth remain connected to the TAC team and are supported as they engage with and adapt to adult services, until healthcare service transitions are complete and confirmed by the youth (and their caregiver(s), where appropriate). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, S.; Orkin, J.; Abells, D.; Allemang, B.; Arenas Rodriguez, B.; Colapinto, K.; Constas, N.; Heath, M.; Henze, M.; John, T.; et al. Building Bridges: Developing and Implementing a New Transition to Adult Care Program for Youth with Complex Healthcare Needs at a Canadian Children’s Hospital. Children 2025, 12, 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081043

Santos S, Orkin J, Abells D, Allemang B, Arenas Rodriguez B, Colapinto K, Constas N, Heath M, Henze M, John T, et al. Building Bridges: Developing and Implementing a New Transition to Adult Care Program for Youth with Complex Healthcare Needs at a Canadian Children’s Hospital. Children. 2025; 12(8):1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Sara, Julia Orkin, Dara Abells, Brooke Allemang, Bianca Arenas Rodriguez, Kimberly Colapinto, Nora Constas, Mackenzie Heath, Megan Henze, Tomisin John, and et al. 2025. "Building Bridges: Developing and Implementing a New Transition to Adult Care Program for Youth with Complex Healthcare Needs at a Canadian Children’s Hospital" Children 12, no. 8: 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081043

APA StyleSantos, S., Orkin, J., Abells, D., Allemang, B., Arenas Rodriguez, B., Colapinto, K., Constas, N., Heath, M., Henze, M., John, T., Lippett, R., Miranda, S., Soscia, J., Teicher, J., Thomson, D., Tyrrell, J., Vandepoele, E., Wentzel, K., Yates, D., ... Toulany, A. (2025). Building Bridges: Developing and Implementing a New Transition to Adult Care Program for Youth with Complex Healthcare Needs at a Canadian Children’s Hospital. Children, 12(8), 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081043