Navigating a New Normal: A Mixed-Methods Study of the Pediatric Tracheostomy Parent-Caregiver Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants, Setting, Approval

2.2. Survey: Design, Distribution, and Data Analysis

2.3. Interviews: Caregiver Participation, Interview Guide Design, and Data Analysis

3. Results

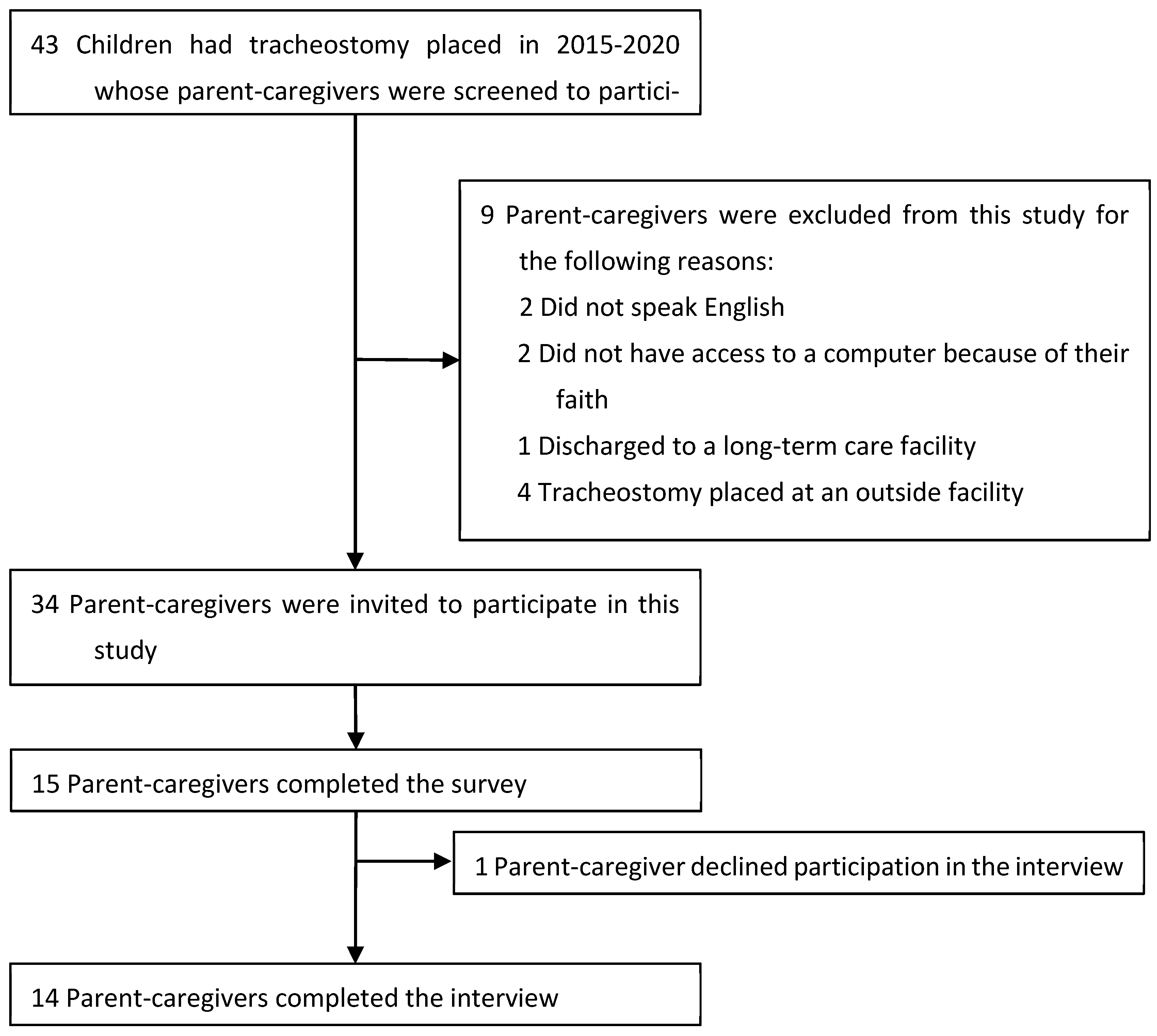

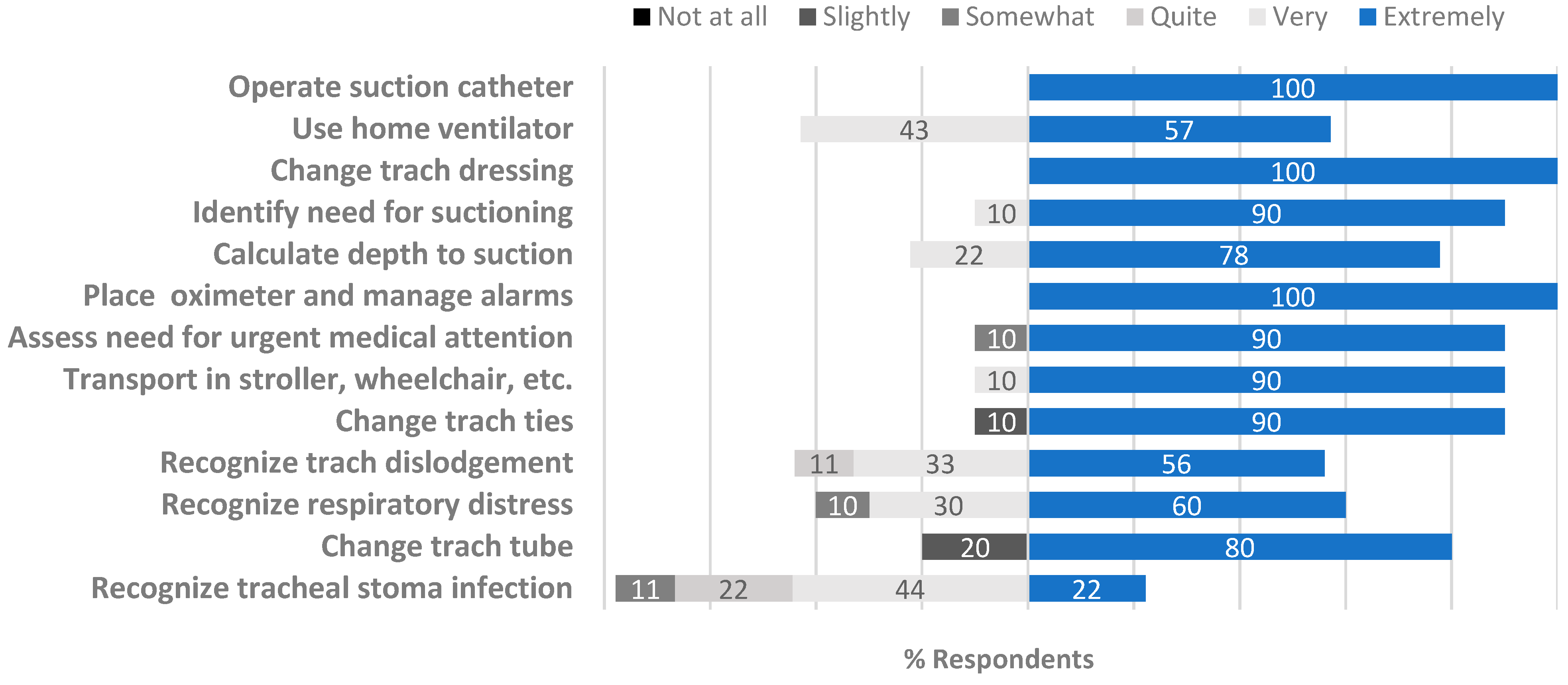

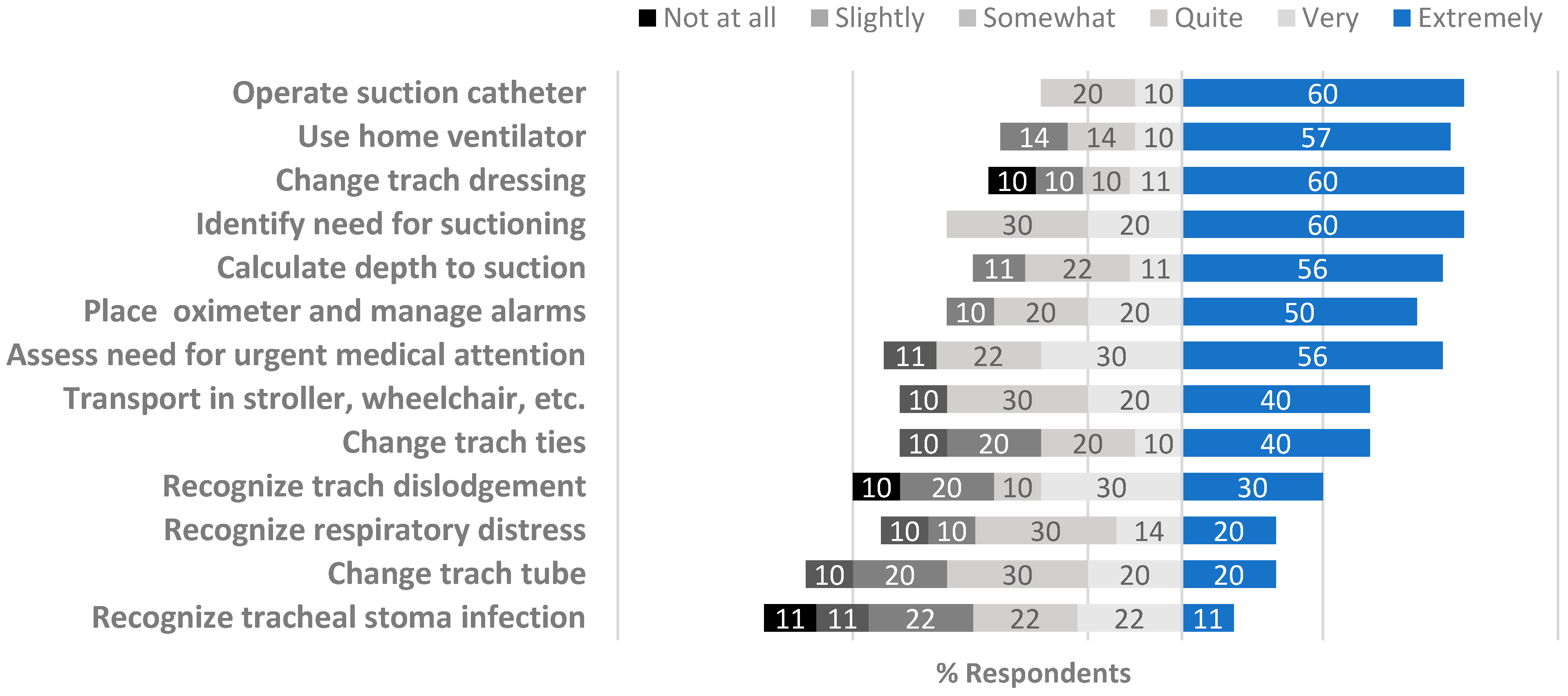

3.1. Survey

3.2. Interviews

3.2.1. Theme: New Identify Formation

3.2.2. Theme: Enduring Education

3.2.3. Theme: Biopsychosocial Support

3.2.4. Theme: Establishing Normalcy

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| For the following questions, confidence is defined as the feeling or belief that you can perform the skill well. Not at all confident: I want to watch someone else perform the skill Slightly confident: I feel comfortable with another caregiver assisting 100% of the skill Moderately confident: I can perform skill with assistance 50% of the time interested in utilizing Quite confident: I can perform skill independently, may need to ask for help or reference training materials Very confident: I feel comfortable performing the skill independently Extremely confident: I feel comfortable performing the skill independently, and can teach the skill to others Please rate your level of confidence for the following tracheostomy skills below | ||||||

| Not at all confident | Slightly confident | Moderately confident | Quite confident | Very confident | Extremely confident | |

| Changing tracheostomy ties | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Changing the tracheostomy dressing | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Recognize signs that could indicate a tracheal stoma infection | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Recognize warning signs of respiratory distress | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Identifying when my child needs to be suctioned | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| My ability to correctly operate suction catheter | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| My ability to calculate the suctioning depth | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Placing a pulse oximeter and managing the alarms | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Recognize and respond to a trach dislodgment | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Using a home ventilator such as LTV or Trilogy | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| My ability to transport my child in stroller, wheelchair, car, etc. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| My ability to assess if my child needs urgent medical attention (call 911, go to Emergency Department) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| How well did the education you received in the hospital prior to discharge prepare you for the following skills when you went home? Not at all prepared: I did not feel comfortable performing this skill Slightly prepared: I could not perform skill independently and needed a second caregiver assisting me with the skill Somewhat prepared: I could perform the skill but preferred that a second caregiver be available as a resource Quite prepared: I was confident performing the skill independently, I would like a second caregiver available as back-up Very prepared: I was confident performing the skill independently, and am confident in being alone with my child Extremely prepared: I was confident being alone with my child and felt confident training other caregivers in the care of my child | ||||||

| Not at all confident | Slightly confident | Moderately confident | Quite confident | Very confident | Extremely confident | |

| Changing tracheostomy ties | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Changing the tracheostomy dressing | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Changing the tracheostomy tube | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Recognize signs that could indicate a tracheal stoma infection | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Recognize warning signs of respiratory distress | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Identifying when my child needs to be suctioned | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| My ability to correctly operate suction catheter | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| My ability to calculate the suctioning depth | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Placing a pulse oximeter and managing the alarms | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Recognize and respond to a trach dislodgment | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Using a home ventilator such as LTV or Trilogy | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| My ability to transport my child in stroller, wheelchair, car, etc. | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| My ability to assess if my child needs urgent medical attention (call 911, go to Emergency Department) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Can you elaborate on situations where you would contact the Ears Nose Throat (ENT) team versus when you would contact the Pulmonary Team (lung team). | ||||||

| The person I would contact if I needed help training a new caregiver in the care of my child’s trach would be... | ||||||

| Please elaborate on any concerns that you have when thinking about caring for your child at home. | ||||||

| Was there anything that you were surprised about when caring for your child at home? | ||||||

| Are there any other topics you would have liked education on? | ||||||

| Having an outpatient option to train additional caregivers (who were not trained as part of the initial hospitalization) is a service that I would be interested in utilizing? | ○Yes ○No | |||||

| Would you be interested in an individual interview where you could talk more about your teaching experience in the hospital and how that prepared you and your family for taking care of your child at home? | ○Yes ○No | |||||

| Interview Question | |

|---|---|

| 1. | How many children with medical needs do you care for? |

| 2. | What are the medical needs of the child/children?

|

| 3. | How long ago was the first discharge home from the hospital? |

| 4. | What training did you receive in the hospital to prepare you for discharge home? Who completed training with you? |

| 5. | Do you feel like you were adequately trained to take your child home from the hospital? Why or why not? |

| 6. | What training do you wish you had received prior to discharge from the hospital, if any? |

| 7. | What additional practice would have been helpful prior to discharge, if any? |

| 8. | What specific training was most helpful to you prior to discharge? |

| 9. | What training was least helpful to you prior to discharge? |

| 10. | Have you experienced any medical emergencies at home with your child?

|

| 11. | On a scale of 1–10 (1 being not making a difference at all, 10 making a significant difference) how much do you think training with a realistic mannequin would have made you feel more prepared for discharge?

|

| 12. | What resources do you use at home to help care for your child? Are there any other resources you wish you had available to you, such as a GCH-specific website, care binder, etc? |

| 13. | Was there anything that surprised you about your child’s care when you got home? |

| 14. | What advice would you give other caregivers preparing to take their child home from the hospital for the first time? |

| 15. | What advice would you give staff at the hospital teaching parents of medically complex children? |

| 16. | What kind of help do you have in the home?

|

References

- Sherman, J.; Zalzal, H.; Bower, K. Equitable Care for Children With a Tracheostomy: Addressing Challenges and Seeking Systemic Solutions. Health Expect 2024, 27, e14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, D.Z.; Houtrow, A.J.; Disabilities, C.O.C.W. Recognition and Management of Medical Complexity. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20163021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, B.; Botos-Kremer, A.I.; Eckel, H.E.; Schlöndorff, G. Indications, complications, and surgical techniques for pediatric tracheostomies—An update. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2002, 37, 1556–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.; Powell, J.; Begbie, J.; Siou, G.; McLarnon, C.; Welch, A.; McKean, M.; Thomas, M.; Ebdon, A.; Moss, S.; et al. Pediatric tracheostomy: A large single-center experience. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, E375–E380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, C.; Wineland, A.M.; Richter, G.T. Update on Pediatric Tracheostomy: Indications, Technique, Education, and Decannulation. Curr. Otorhinolaryngol. Rep. 2021, 9, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spratling, R. Understanding the health care utilization of children who require medical technology: A descriptive study of children who require tracheostomies. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 34, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.B.; Hussey, H.M.; Setzen, G.; Jacobs, I.N.; Nussenbaum, B.; Dawson, C.; Brown, C.A., 3rd; Brandt, C.; Deakins, K.; Hartnick, C.; et al. Clinical Consensus Statement: Tracheostomy Care. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 149, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, S.; Shermont, H.; Hockman, G.; Hamilton, S.; Abecassis, L.; Blanchette, S.; Munhall, D. Standardized Tracheostomy Education Across the Enterprise. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 43, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolomeo, C.; Major, N.E.; Szondy, M.V.; Bazzy-Asaad, A. Standardizing Care and Parental Training to Improve Training Duration, Referral Frequency, and Length of Stay: Our Quality Improvement Project Experience. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 32, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nageswaran, S.; Golden, S.L.; Gower, W.A.; King, N.M. Caregiver Perceptions about their Decision to Pursue Tracheostomy for Children with Medical Complexity. J. Pediatr. 2018, 203, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acorda, D.E.; Jackson, A.; Lam, A.K.; Molchen, W. Overwhelmed to ownership: The lived experience of parents learning to become caregivers of children with tracheostomies. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 163, 111364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, M.; Kubba, H. Psychological Challenges in Children with Tracheostomies and Their Families—A Qualitative Study. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2025, 50, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.D.; Durkin, L.K.; Jacob-Files, E.A.; Mangione-Smith, R. Caregiver Perceptions of Hospital to Home Transitions According to Medical Complexity: A Qualitative Study. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, I.; Wray, J.; Kenny, M.; Hewitt, R.; Hall, A.; Cooke, J. Hospital training and preparedness of parents and carers in paediatric tracheostomy care: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 154, 111058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Orne, J.A.; Clutter, P.; Fredland, N.; Schultz, R. Caring for the child with a tracheostomy through the eyes of their caregiver: A photovoice study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2024, 79, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanathan, D.; Bruckman, D.; Appachi, S.; Hopkins, B. Association of Discharge Location Following Pediatric Tracheostomy with Social Determinants of Health: A National Analysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2024, 170, 522–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecil, C.A.; Dziorny, A.C.; Hall, M.; Kane, J.M.; Kohne, J.; Olszewski, A.E.; Rogerson, C.M.; Slain, K.N.; Toomey, V.; Goodman, D.M.; et al. Low-Resource Hospital Days for Children Following New Tracheostomy. Pediatrics 2024, 154, e2023064920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, A.F.; Smith, S.N. Person-first language: Are we practicing what we preach? J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2019, 12, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickards, G.; Magee, C.; Artino, A.R., Jr. You Can’t Fix by Analysis What You’ve Spoiled by Design: Developing Survey Instruments and Collecting Validity Evidence. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E.S. Corporation. MyChart. Available online: https://www.epic.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Z. Communications. Zoom. Available online: https://www.zoom.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- R. Communications. Available online: https://www.rev.com/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Charmaz, K. Teaching Theory Construction with Initial Grounded Theory Tools: A Reflection on Lessons and Learning. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merriam, S.B.; Elizabeth, J. Qualitative Research. In A Guide to Design and Implementation; Jossey-Bass: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Verdinelli, S.; Scagnoli, N.I. Data Display in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2013, 12, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkan, J.M. Immersion–Crystallization: A valuable analytic tool for healthcare research. Fam. Pr. 2022, 39, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.; Shah, G.B.; Mitchell, R.B.; Lenes-Voit, F.; Johnson, R.F. The Incidence of Pediatric Tracheostomy and Its Association Among Black Children. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 164, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebbar, K.B.; Kasi, A.S.; Vielkind, M.; McCracken, C.E.; Ivie, C.C.; Prickett, K.K.; Simon, D.M. Mortality and Outcomes of Pediatric Tracheostomy Dependent Patients. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 661512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, R.G.; Mamidala, M.P.; Smith, S.H.; Smith, A.; Sheyn, A. Incidence, Epidemiology, and Outcomes of Pediatric Tracheostomy in the United States from 2000 to 2012. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 160, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, A.; Kozhumam, A.S.; Seeler, E.; Docherty, S.L.; Brandon, D. Multiple Roles of Parental Caregivers of Children with Complex Life-Threatening Conditions: A Qualitative Descriptive Analysis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 61, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobotka, S.A.; Dholakia, A.; Berry, J.G.; Brenner, M.; Graham, R.J.; Goodman, D.M.; Agrawal, R.K. Home nursing for children with home mechanical ventilation in the United States: Key informant perspectives. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 3465–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N.Y. State. Private Duty Nursing Policy Manual; Department of Health: New York, NY, USA, 2025.

- Juraschek, S.P.; Zhang, X.; Ranganathan, V.; Lin, V.W. Republished: United States Registered Nurse Workforce Report Card and Shortage Forecast. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2019, 34, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amar-Dolan, L.G.; Horn, M.H.; O’cOnnell, B.; Parsons, S.K.; Roussin, C.J.; Weinstock, P.H.; Graham, R.J. “This Is How Hard It Is”. Family Experience of Hospital-to-Home Transition with a Tracheostomy. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 17, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baddour, K.; Mady, L.J.; Schwarzbach, H.L.; Sabik, L.M.; Thomas, T.H.; McCoy, J.L.; Tobey, A. Exploring caregiver burden and financial toxicity in caregivers of tracheostomy-dependent children. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 145, 110713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, C.C.; Chorniy, A.; Kwon, S.; Kan, K.; Heard-Garris, N.; Davis, M.M.M. Children with Special Health Care Needs and Forgone Family Employment. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2020035378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truitt, B.A.; Ghosh, R.N.; Price, E.W.; Du, C.; Bai, S.; Greene, D.; Simon, D.M.; Reeder, W.; Kasi, A.S. Family Caregiver Knowledge in the Outpatient Management of Pediatric Tracheostomy-Related Emergencies. Clin. Pediatr. 2025, 64, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huestis, M.J.; Kahn, C.I.; Tracy, L.F.; Levi, J.R. Facebook Group Use among Parents of Children with Tracheostomy. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 162, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acorda, D.E.; Van Orne, J. Pediatric Tracheostomy Education Program Structures, Barriers, and Support: A Nationwide Survey of Children’s Hospitals. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2025, 172, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basak, R.B.; Momaya, R.; Guo, J.; Rathi, P. Role of Child Life Specialists in Pediatric Palliative Care. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2019, 58, 735–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek-Shriber, L. Parent Stress in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and the Influence of Parent and Infant Characteristics. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2004, 58, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilling, V.; Morris, C.; Thompson-Coon, J.; Ukoumunne, O.; Rogers, M.; Logan, S. Peer support for parents of children with chronic disabling conditions: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2013, 55, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parent to Parent USA. 2025, Cited 2024. Available online: https://www.p2pusa.org/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- CPBF Canadian Premature Babies Foundation. 2025. Available online: https://www.cpbf-fbpc.org/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- McKeon, M.; Kohn, J.; Munhall, D.; Wells, S.; Blanchette, S.; Santiago, R.; Graham, R.; Nuss, R.; Rahbar, R.; Volk, M.; et al. Association of a Multidisciplinary Care Approach with the Quality of Care After Pediatric Tracheostomy. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abode, K.A.; Drake, A.F.; Zdanski, C.J.; Retsch-Bogart, G.Z.; Gee, A.B.; Noah, T.L. A Multidisciplinary Children’s Airway Center: Impact on the Care of Patients With Tracheostomy. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20150455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franck, L.S.; Axelin, A.; Van Veenendaal, N.R.; Bacchini, F. Improving Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Quality and Safety with Family-Centered Care. Clin. Perinatol. 2023, 50, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, A.F.; Farkas, J.S.; Mendelsohn, A.L.; Fierman, A.H.; Tomopoulos, S.; Rosenberg, R.E.; Dreyer, B.P.; Melgar, J.; Varriano, J.; Yin, H.S. Discharge Instruction Comprehension and Adherence Errors: Interrelationship Between Plan Complexity and Parent Health Literacy. J. Pediatr. 2019, 214, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keim-Malpass, J.; Letzkus, L.C.; Kennedy, C. Parent/caregiver health literacy among children with special health care needs: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzban, S.; Najafi, M.; Agolli, A.; Ashrafi, E. Impact of Patient Engagement on Healthcare Quality: A Scoping Review. J. Patient Exp. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Median (Q1, Q3) n = 15 |

|---|---|

| Age (months) When obtained tracheostomy At time of study | 4 (3, 6) 46 (30, 59) |

| Time in hospital (months) After obtained tracheostomy Total length of stay | 3 (2, 6) 6 (5, 10) |

| Time at home, since hospital discharge (months) | 42 (18, 54) |

| Characteristics | n (%) n = 15 |

|---|---|

| Location at time of tracheostomy Neonatal intensive care unit Pediatric cardiac intensive care unit Pediatric intensive care unit | 10 (67) 2 (13) 3 (20) |

| Location of caregiver education Neonatal intensive care unit Pediatric cardiac intensive care unit Pediatric intensive care unit Pediatric floor | 6 (40) 4 (27) 4 (27) 1 (6) |

| Theme | Subtheme | Interview Excerpts |

|---|---|---|

| New identity formation | Caregiver |

|

| Educator |

| |

| Employer and Entrepreneur |

| |

| Enduring education | Experiential learning |

|

| Confidence development over time |

| |

| Parenting versus caregiving |

| |

| Child and family biopsychosocial support | Peer support (Child and Caregiver) |

|

| Compassion and respect |

| |

| Establishing normalcy | Simultaneous opposing emotions (fear, anxiety, excitement, relief) |

|

| Routine |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

DiNoto, L.; Frankel, A.; Wheaton, T.; Smith, D.; Buholtz, K.; Dadiz, R.; Palumbo, K. Navigating a New Normal: A Mixed-Methods Study of the Pediatric Tracheostomy Parent-Caregiver Experience. Children 2025, 12, 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070956

DiNoto L, Frankel A, Wheaton T, Smith D, Buholtz K, Dadiz R, Palumbo K. Navigating a New Normal: A Mixed-Methods Study of the Pediatric Tracheostomy Parent-Caregiver Experience. Children. 2025; 12(7):956. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070956

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiNoto, Laine, Adrianne Frankel, Taylor Wheaton, Desirae Smith, Kimberly Buholtz, Rita Dadiz, and Kathryn Palumbo. 2025. "Navigating a New Normal: A Mixed-Methods Study of the Pediatric Tracheostomy Parent-Caregiver Experience" Children 12, no. 7: 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070956

APA StyleDiNoto, L., Frankel, A., Wheaton, T., Smith, D., Buholtz, K., Dadiz, R., & Palumbo, K. (2025). Navigating a New Normal: A Mixed-Methods Study of the Pediatric Tracheostomy Parent-Caregiver Experience. Children, 12(7), 956. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070956