Caries Rates in Different School Environments Among Older Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northeast Germany †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

- Regional school (“Regionale Schule”): A type of secondary school including grades 5 to 10. Its certificate allows either joining a higher school or vocational school.

- Comprehensive school (“Gesamtschule”): A type of school including all learning tracks and integrating all academic levels, including a proportion of children with mental or physical disabilities.

- High school (“Gymnasium”): An academically demanding secondary school preparing the students for university education, including grades 5–12.

- School for special educational needs (“Förderschule”): Schools especially designed for children with learning disabilities, speech and language challenges, or developmental delays. It promotes the individual needs of the children and has different categorizations of the grades based on performance not age.

- Vocational school (“Berufsschule”): A type of dual education system combining theoretical learning with practical job training, which is usually between 2 and 4 years after the age of 15.

2.2. Clinical Examination

- S: The tooth is healthy

- U: The tooth is not yet assessable (unerupted)

- D: Dental caries with cavity (ICDAS 3 and above)

- Z: Tooth destructed due to caries (tooth not restorable)

- F: Filled tooth (or covered with a crown)

- M: Extracted tooth due to caries

- Y: Extracted tooth due to orthodontic reasons

- I: Initial caries (ICDAS 1 or 2)

- H: Hypoplasia (including molar incisor hypomineralization)

- V: Fissure sealant

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Adolescents of the Eleventh and Twelfth Grades (16–18 Years Old)

3.2. Results of the Adolescents up to the Tenth Grade (11–15 Years Old)

3.3. Differences in D3MFT Between the Different School Types

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators; Bernabe, E.; Marcenes, W.; Hernandez, C.R.; Bailey, J.; Abreu, L.G.; Alipour, V.; Amini, S.; Arabloo, J.; Arefi, Z.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Levels and Trends in Burden of Oral Conditions from 1990 to 2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminia, M.; Abdi, A.; Shohaimi, S.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Salari, N.; Mohammadi, M. Dental caries in primary and permanent teeth in children’s worldwide, 1995 to 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Face Med. 2020, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.R.; Meyer-Lueckel, H.; Kuhr, K.; Sasunna, D.; Bekes, K.; Schiffner, U. Caries experience and care in Germany: Results of the 6th German Oral Health Study (DMS · 6). Quintessence Int. 2025, 56, S30–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang Le, V.N.; Kim, J.G.; Yang, Y.M.; Lee, D.W. Risk Factors for Early Childhood Caries: An Umbrella Review. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 43, 176–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Hou, R.; Yang, T.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Shi, X.; Zhao, B.; Liu, J. Effect of dietary patterns on dental caries among 12–15 years-old adolescents: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiv, M.-P.S.O. Statistical Reports; A—Population, Healthcare, Territory, Employment. Available online: https://www.laiv-mv.de/static/LAIV/Statistik/Dateien/Publikationen/A%20I%20Bev%C3%B6lkerungsstand/A113/A113%202023%2000.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- DAJ. Epidemiological Studies Accompanying Group Prophylaxis in Germany. Available online: https://daj.de/gruppenprophylaxe/epidemiologische-studien/ (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Ismail, A.I.; Sohn, W.; Tellez, M.; Amaya, A.; Sen, A.; Hasson, H.; Pitts, N.B. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS): An integrated system for measuring dental caries. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- InformationsSystem GesundheitsAmt (ISGA®), Version 5. Computer Zentrum Strausberg GmbH: Strausberg, Germany. Available online: https://www.computerzentrum.de/gesundheitsaemter (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Schmoeckel, J.; Santamaria, R.M.; Basner, R.; Schuler, E.; Splieth, C.H. Introducing a Specific Term to Present Caries Experience in Populations with Low Caries Prevalence: Specific Affected Caries Index (SaC). Caries Res. 2019, 53, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria, R.M.; Splieth, C.H.; Basner, R.; Schankath, E.; Schmoeckel, J. Caries Level in 3-Year-Olds in Germany: National Caries Trends and Gaps in Primary Dental Care. Children 2024, 11, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesundheit Österreich GmbH. Dental Treatments; Gesundheit Österreich GmbH: Wien, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Donadeu, M.; Ribas-Perez, D.; Rodriguez Menacho, D.; Villalva Hernandez-Franch, P.; Barbero Navarro, I.; Castano-Seiquer, A. Epidemiological Study of Oral Health among Children and Adolescent Schoolchildren in Melilla (Spain). Healthcare 2023, 11, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, K.; Christensen, L.B.; Mortensen, L.H.; Skovgaard, L.T.; Andersen, I. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in oral health among 15-year-old Danish adolescents during 1995–2013: A nationwide, register-based, repeated cross-sectional study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2017, 45, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamipour, F.; Borzabadi-Farahani, A.; Asgari, I. The relationship between aging and oral health inequalities assessed by the DMFT index. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2010, 11, 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Klaric Puda, I.; Gorseta, K.; Juric, H.; Soldo, M.; Marks, L.A.M.; Majstorovic, M. A Cohort Study on the Impact of Oral Health on the Quality of Life of Adolescents and Young Adults. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndagire, B.; Kutesa, A.; Ssenyonga, R.; Kiiza, H.M.; Nakanjako, D.; Rwenyonyi, C.M. Prevalence, Severity and Factors Associated with Dental Caries Among School Adolescents in Uganda: A Cross-Sectional Study. Braz. Dent. J. 2020, 31, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukacs, J.R.; Largaespada, L.L. Explaining sex differences in dental caries prevalence: Saliva, hormones, and “life-history” etiologies. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2006, 18, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Mier, E.A.; Zandona, A.F. The impact of gender on caries prevalence and risk assessment. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 57, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, J.R.; Leslie, E.J.; Feingold, E.; Govil, M.; McNeil, D.W.; Crout, R.J.; Weyant, R.J.; Marazita, M.L. Caries Experience Differs between Females and Males across Age Groups in Northern Appalachia. Int. J. Dent. 2015, 2015, 938213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, K.R.; Bruun, G.; Bruun, M. Plaque and gingival status as indicators for caries progression on approximal surfaces. Caries Res. 1998, 32, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw Myint, Z.C.; Zaitsu, T.; Oshiro, A.; Ueno, M.; Soe, K.K.; Kawaguchi, Y. Risk indicators of dental caries and gingivitis among 10–11-year-old students in Yangon, Myanmar. Int. Dent. J. 2020, 70, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre Kramer, A.C.; Pivodic, A.; Hakeberg, M.; Ostberg, A.L. Multilevel Analysis of Dental Caries in Swedish Children and Adolescents in Relation to Socioeconomic Status. Caries Res. 2019, 53, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwendicke, F.; Dorfer, C.E.; Schlattmann, P.; Foster Page, L.; Thomson, W.M.; Paris, S. Socioeconomic inequality and caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splieth, C.H.; Santamaria, R.M.; Basner, R.; Schuler, E.; Schmoeckel, J. 40-Year Longitudinal Caries Development in German Adolescents in the Light of New Caries Measures. Caries Res. 2019, 53, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, B.; Adam, T.R.; Bustami, R. Caries prevalence among children at public and private primary schools in Riyadh: A retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagheri, D.; Hahn, P.; Hellwig, E. Assessing the oral health of school-age children and the current school-based dental screening programme in Freiburg (Germany). Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2007, 5, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmoeckel, J.; Wahl, G.; Santamaria, R.M.; Basner, R.; Schankath, E.; Splieth, C.H. Influence of School Type and Class Level on Mean Caries Experience in 12-Year-Olds in Serial Cross-Sectional National Oral Health Survey in Germany-Proposal to Adjust for Selection Bias. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielnik-Blaszczak, M.; Rudnicka-Siwek, K.; Warsz, M.; Struska, A.; Krajewska-Kurzepa, A.; Pels, E. Evaluation of oral cavity condition with regard to decay in 18-year old from urban and rural areas in Podkarpackie Province, Poland. Prz. Epidemiol. 2016, 70, 53–58, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Scibak, A.; Kuczynska, E.; Bachanek, T. Health of the oral cavity of 18-years old students in vocational schools without dental care. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Sklodowska Sect. D Med. 2003, 58, 364–369. [Google Scholar]

- Dettori, M.; Arghittu, A.; Cappai, A.; Castiglia, P.; Campus, G.; Children’s Smiles Sardinian, G. Impact of Socioeconomic Inequalities on Dental Caries Status in Sardinian Children. Children 2024, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallestal, C.; Wall, S. Socio-economic effect on caries. Incidence data among Swedish 12–14-year-olds. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2002, 30, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasireddy, D.; Sathiyakumar, T.; Mondal, S.; Sur, S. Socioeconomic Factors Associated with the Risk and Prevalence of Dental Caries and Dental Treatment Trends in Children: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) Data, 2016–2019. Cureus 2021, 13, e19184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

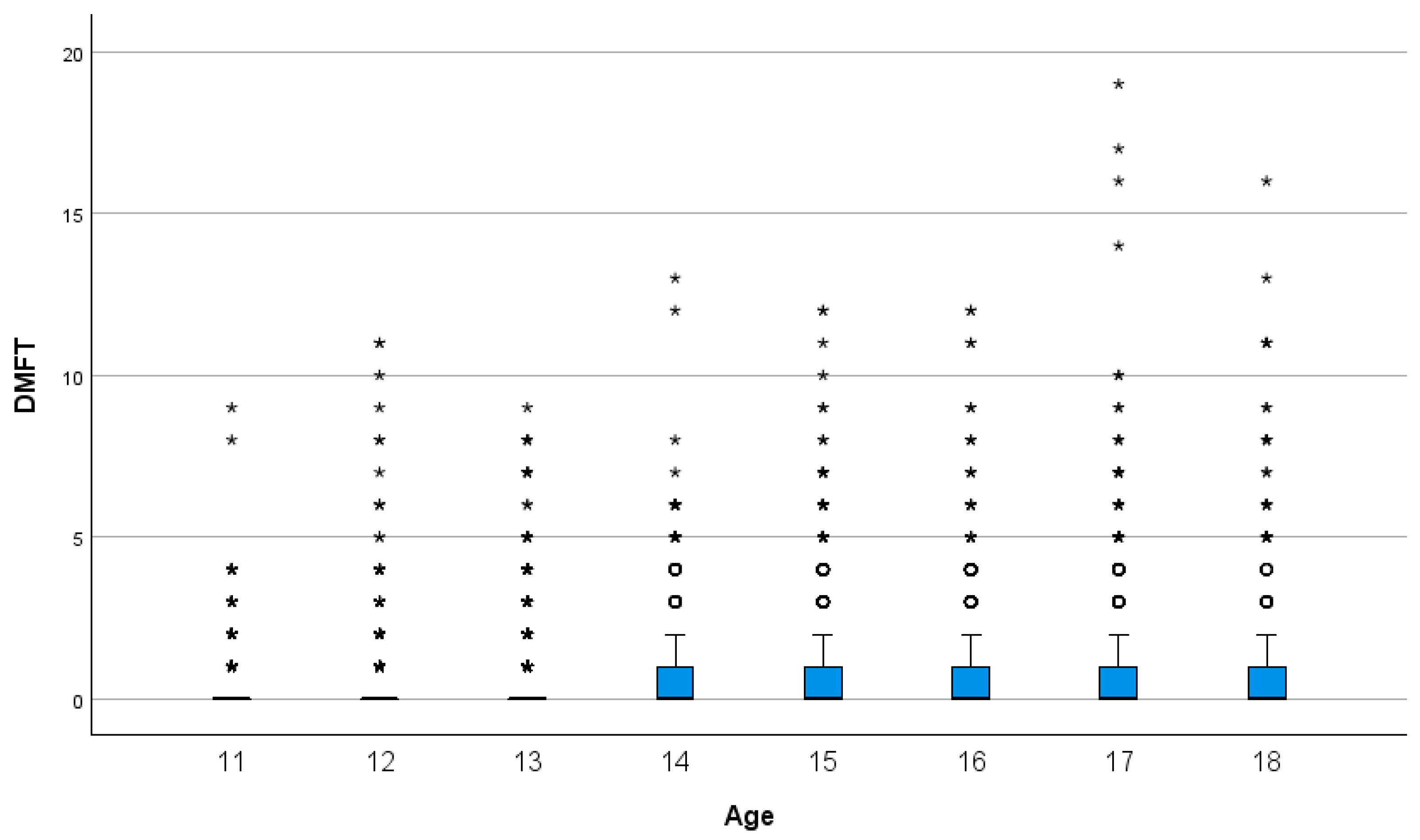

| Age Group | N | Female | DMFT = 0 | Mean D3MFT | Mean ID3MFT | Mean D3T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 633 (10.9) | 328 (51.8) | 536 (84.7) | 0.28 ± 0.85 | 1.09 ± 1.73 | 0.11 ± 0.58 |

| 12 | 917 (15.8) | 431 (47) | 724 (79.0) | 0.46 ± 1.22 | 1.22 ± 2.02 | 0.16 ± 0.79 |

| 13 | 1018 (17.5) | 519 (51) | 796 (78.2) | 0.48 ± 1.20 | 1.48 ± 2.32 | 0.15 ± 0.68 |

| 14 | 962 (16.5) | 440 (45.7) | 704 (73.2) | 0.6 ± 1.34 | 1.89 ± 2.81 | 0.17 ± 0.62 |

| 15 | 808 (13.9) | 387 (47.9) | 559 (69.2) | 0.81 ± 1.67 | 2.15 ± 3.07 | 0.15 ± 0.64 |

| 16 | 660 (11.3) | 308 (46.7) | 460 (69.7) | 0.8 ± 1.70 | 2.27 ± 3.39 | 0.15 ± 0.58 |

| 17 | 508 (8.7) | 266 (52.4) | 324 (63.8) | 1.1 ± 2.26 | 2.78 ± 3.74 | 0.24 ± 1.05 |

| 18 | 310 (5.3) | 153 (49.4) | 189 (61.0) | 1.25 ± 2.39 | 3.27 ± 4.12 | 0.21 ± 0.81 |

| Total | 5816 (100) | 2832 (48.7) | 4292 (73.8) | 0.65 ± 1.55 | 1.85 ± 2.88 | 0.16 ± 0.71 |

| Age Group | SaC Index a | Mean DT If D3MFT > 0 | N if D3T > 0 (%) | Mean D3MFT If D3T > 0 (SD) | Mean D3T If D3T > 0 (SD) | Care Index b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 1.84 ± 1.36 | 0.7 ± 1.35 | 40 (6.3) | 2.13 ± 1.77 | 1.7 ± 1.65 | 61.8 |

| 12 | 2.21 ± 1.80 | 0.78 ± 1.57 | 72 (7.9) | 2.78 ± 2.50 | 2.1 ± 1.96 | 64.6 |

| 13 | 2.2 ± 1.67 | 0.7 ± 1.31 | 84 (8.3) | 2.57 ± 2.12 | 1.86 ± 1.55 | 68.0 |

| 14 | 2.24 ± 1.75 | 0.64 ± 1.06 | 97 (10.1) | 2.65 ± 1.95 | 1.7 ± 1.08 | 71.4 |

| 15 | 2.64 ± 2.07 | 0.5 ± 1.08 | 69 (8.5) | 3.29 ± 2.57 | 1.81 ± 1.36 | 80.8 |

| 16 | 2.66 ± 2.15 | 0.49 ± 0.97 | 59 (8.9) | 2.88 ± 2.35 | 1.66 ± 1.11 | 81.5 |

| 17 | 3.05 ± 2.86 | 0.67 ± 1.66 | 47 (9.3) | 4.28 ± 3.66 | 2.62 ± 2.40 | 77.9 |

| 18 | 3.2 ± 2.91 | 0.54 ± 1.23 | 34 (11.0) | 4.03 ± 3.56 | 1.91 ± 1.66 | 83.2 |

| Total | 2.5 ± 2.13 | 0.62 ± 1.28 | 502 (8.6) | 2.97 ± 2.56 | 1.89 ± 1.60 | 75.0 |

| OR | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age, years | 1.261 | 1.217 | 1.307 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 1.278 | 1.129 | 1.446 | <0.001 |

| Plaque, yes | 1.291 | 1.095 | 1.522 | 0.002 |

| Gingivitis, yes | 1.240 | 1.048 | 1.468 | 0.012 |

| Regional school | 1-Reference | |||

| Comprehensive school | 0.737 | 0.625 | 0.868 | <0.001 |

| High school | 0.423 | 0.359 | 0.499 | <0.001 |

| Vocational school | 1.058 | 0.778 | 1.439 | 0.719 |

| School for special educational needs | 1.592 | 1.227 | 2.067 | <0.001 |

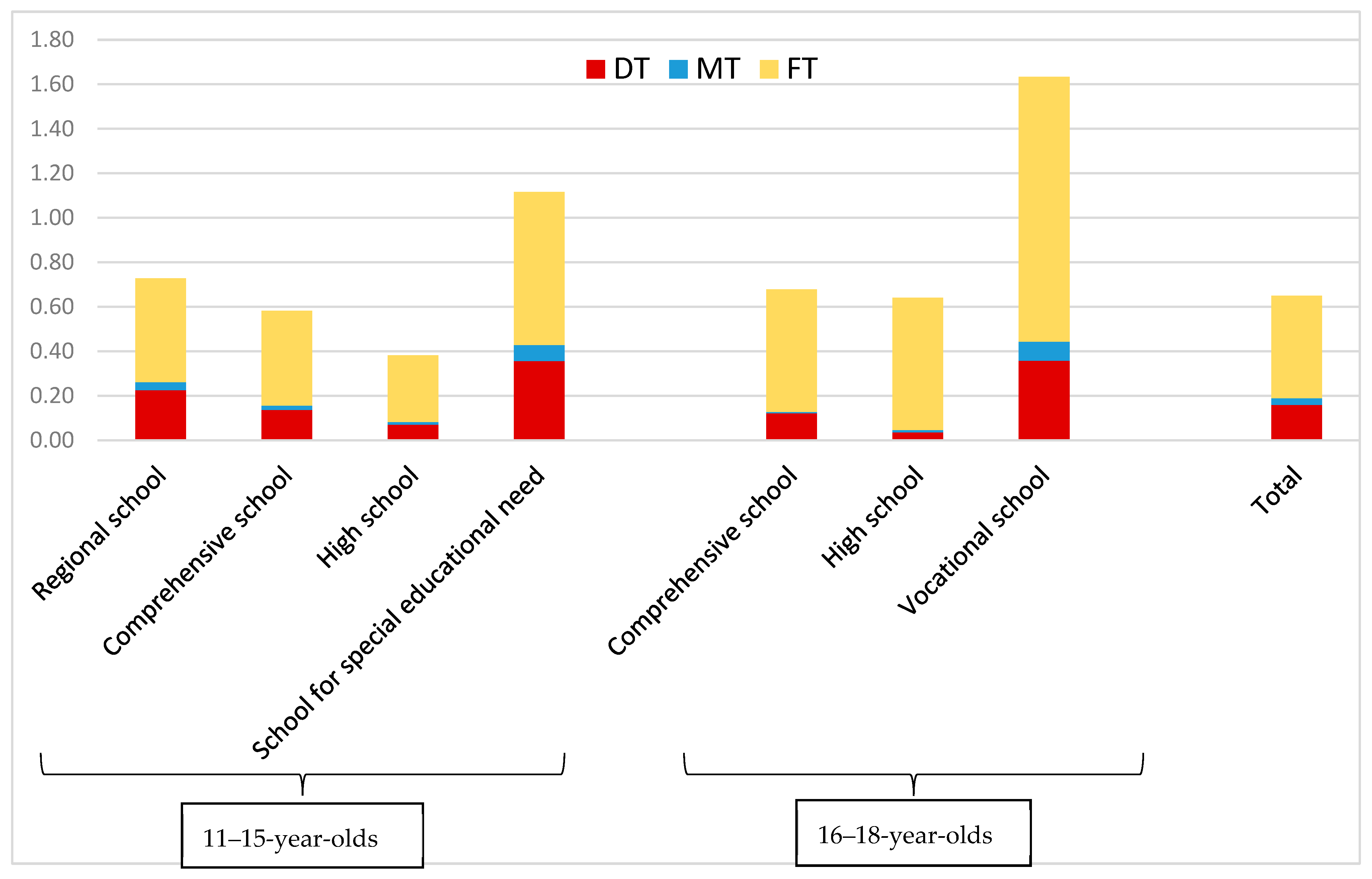

| Category | Variables | Comprehensive School | High School | Vocational School | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 67 (48.2) | 179 (43.8) | 120 (49.4) | 366 (46.3) | 0.335 a |

| Female | 72 (51.8) | 230 (56.2) | 123 (50.6) | 425 (53.7) | ||

| Plaque | Yes | 48 (34.5) | 121 (29.6) | 92 (37.9) | 261 (33) | 0.086 a |

| No | 91 (65.5) | 288 (70.4) | 151 (62.1) | 530 (67) | ||

| Gingivitis | Yes | 68 (48.9) | 185 (45.2) | 120 (49.4) | 373 (47.2) | 0.531 a |

| No | 71 (51.1) | 224 (54.8) | 123 (50.6) | 418 (52.8) | ||

| D3MFT | D3MFT = 0 | 97 (69.8) | 306 (74.8) | 120 (49.4) | 523 (66.1) | <0.001 a |

| D3MFT > 0 | 42 (30.2) | 103 (25.2) | 123 (50.6) | 268 (33.9) | ||

| Age | 17.38 ± 0.65 | 17.8 ± 0.52 | 17.82 ± 0.73 | 17.73 ± 0.63 | <0.001 b | |

| D3T | 0.12 ± 0.44 | 0.04 ± 0.23 | 0.36 ± 1.13 | 0.15 ± 0.69 | <0.001 c | |

| MT | 0.01 ± 0.08 | 0.01 ± 0.12 | 0.09 ± 0.41 | 0.03 ± 0.25 | <0.001 c | |

| FT | 0.55 ± 1.74 | 0.59 ± 1.42 | 1.19 ± 2.02 | 0.77 ± 1.7 | <0.001 c | |

| D3MFT | 0.68 ± 191 | 0.64 ± 1.49 | 1.63 ± 2.55 | 0.95 ± 1.99 | <0.001 c | |

| ID3MFT | 2.32 ± 2.91 | 1.67 ± 2.44 | 4.37 ± 4.81 | 2.61 ± 3.61 | <0.001 c | |

| OR | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Comprehensive School | 1-Reference | |||

| High School | 0.746 | 0.480 | 1.160 | 0.193 |

| Vocational School | 2.251 | 1.427 | 3.551 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 1.308 | 0.955 | 1.792 | 0.095 |

| Plaque, yes | 0.659 | 0.430 | 1.010 | 0.055 |

| Gingivitis, yes | 0.912 | 0.605 | 1.375 | 0.660 |

| Age, years | 1.129 | 0.883 | 1.444 | 0.333 |

| Category | Variables | Regional School | Comprehensive School | High School | School for Special Educational Needs | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1028 (53.9) | 612 (51.2) | 785 (48.2) | 193 (66.3) | 2618 (52.1) | <0.001 a |

| Female | 880 (46.1) | 584 (48.8) | 844 (51.8) | 98 (33.7) | 2406 (47.9) | ||

| Plaque | Yes | 984 (51.6) | 603 (50.4) | 664 (40.8) | 176 (60.5) | 2427 (48.3) | <0.001 a |

| No | 924 (48.4) | 593 (49.6) | 965 (59.2) | 115 (39.5) | 2597 (51.7) | ||

| Gingivitis | Yes | 1186 (62.2) | 700 (58.5) | 874 (53.7) | 206 (70.8) | 2966 (59) | <0.001 a |

| No | 722 (37.8) | 496 (41.5) | 755 (46.3) | 85 (29.2) | 2058 (41) | ||

| D3MFT | D3MFT = 0 | 1362 (71.4) | 903 (75.5) | 1330 (81.6) | 173 (59.5) | 3768 (75) | <0.001 a |

| D3MFT > 0 | 546 (28.6) | 293 (24.5) | 299 (18.4) | 118 (40.5) | 1256 (25) | ||

| Age | 13.62 ± 1.63 | 13.74 ± 1.63 | 14.68 ± 1.39 | 13.96 ± 1.73 | 14.01 ± 1.63 | <0.001 b | |

| D3T | 0.23 ± 0.84 | 0.14 ± 0.59 | 0.07 ± 0.49 | 0.36 ± 0.96 | 0.17 ± 0.71 | <0.001 b | |

| MT | 0.04 ± 0.26 | 0.02 ± 0.17 | 0.01 ± 0.13 | 0.07 ± 0.36 | 0.03 ± 0.22 | <0.001 b | |

| FT | 0.47 ± 1.14 | 0.43 ± 1.22 | 0.30 ± 0.97 | 0.69 ± 1.48 | 0.42 ± 1.14 | <0.001 b | |

| D3MFT | 0.73 ± 1.57 | 0.58 ± 1.46 | 0.39 ± 1.17 | 1.12 ± 1.9 | 0.61 ± 1.46 | <0.001 b | |

| ID3MFT | 1.89 ± 2.82 | 1.63 ± 2.55 | 1.42 ± 2.57 | 2.93 ± 3.36 | 1.74 ± 2.73 | <0.001 b | |

| OR | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Regional school | 1-Reference | |||

| Comprehensive school | 0.777 | 0.656 | 0.921 | 0.004 |

| High school | 0.430 | 0.363 | 0.510 | <0.001 |

| School for special educational needs | 1.583 | 1.218 | 2.059 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 1.287 | 1.124 | 1.474 | <0.001 |

| Plaque, yes | 1.233 | 1.031 | 1.475 | 0.022 |

| Gingivitis, yes | 1.275 | 1.059 | 1.535 | 0.010 |

| Age, years | 1.317 | 1.263 | 1.374 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Masri, A.; Splieth, C.H.; Pink, C.; Younus, S.; Alkilzy, M.; Vielhauer, A.; Abdin, M.; Basner, R.; Mourad, M.S. Caries Rates in Different School Environments Among Older Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northeast Germany. Children 2025, 12, 1014. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081014

Al Masri A, Splieth CH, Pink C, Younus S, Alkilzy M, Vielhauer A, Abdin M, Basner R, Mourad MS. Caries Rates in Different School Environments Among Older Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northeast Germany. Children. 2025; 12(8):1014. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081014

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Masri, Ahmad, Christian H. Splieth, Christiane Pink, Shereen Younus, Mohammad Alkilzy, Annina Vielhauer, Maria Abdin, Roger Basner, and Mhd Said Mourad. 2025. "Caries Rates in Different School Environments Among Older Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northeast Germany" Children 12, no. 8: 1014. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081014

APA StyleAl Masri, A., Splieth, C. H., Pink, C., Younus, S., Alkilzy, M., Vielhauer, A., Abdin, M., Basner, R., & Mourad, M. S. (2025). Caries Rates in Different School Environments Among Older Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Northeast Germany. Children, 12(8), 1014. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081014