The Impact of Physical Activity on Suicide Attempt in Children: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Suicidality in Children

1.2. Predictors of Suicide

1.3. Biopsychosocial Model of Suicide

1.4. PA Definitions

1.5. PA in the Context of Suicidality

1.6. Gap in the Literature

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Methodological Quality Assessment

3. Results

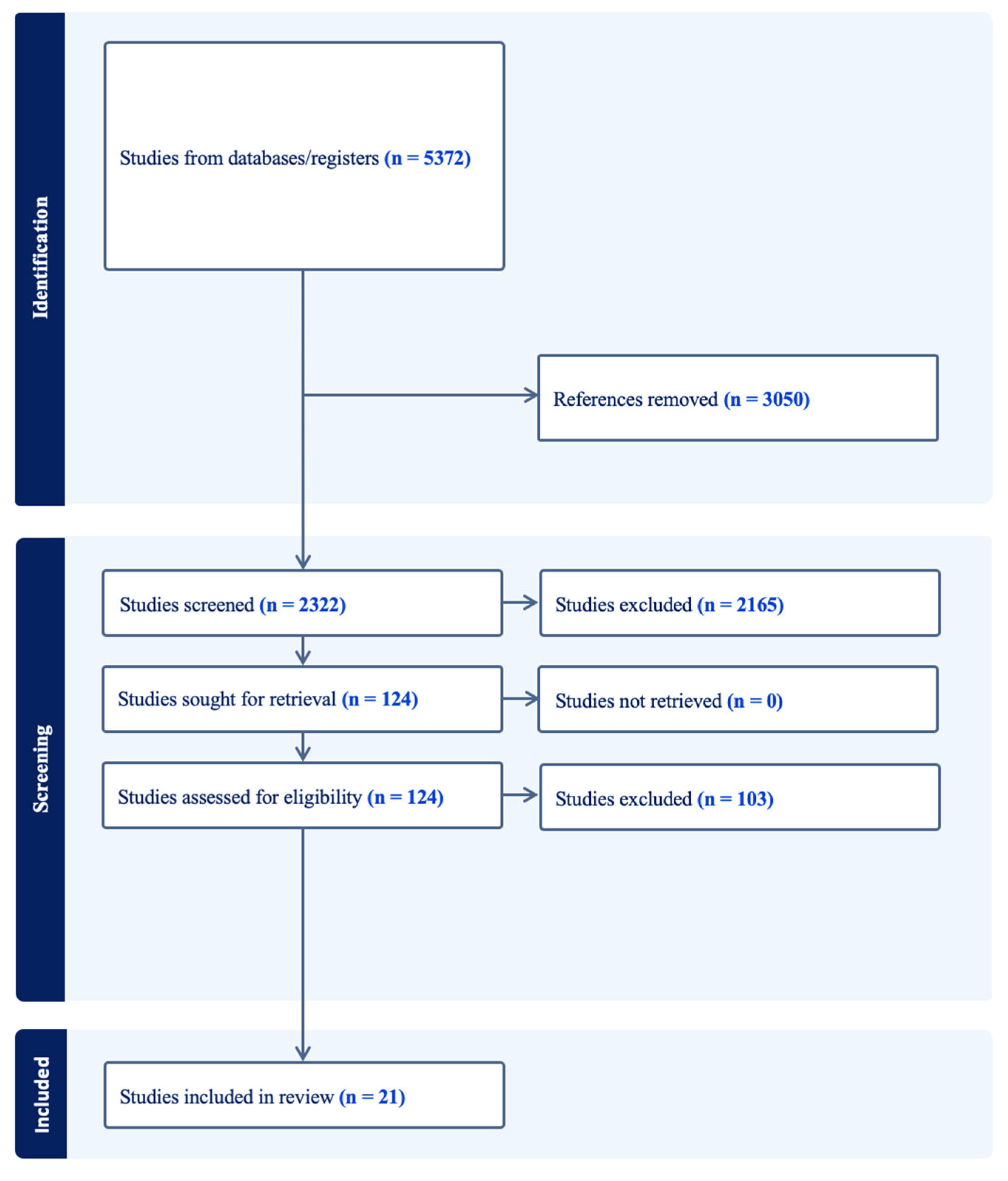

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Demographics and Study Design

3.3. Independent Variable (PA)

3.4. Dependent Variable (SA)

3.5. Increase in PA Reduces SA (Inverse Relationship)

3.6. Increase in PA Increases SA (Direct Relationship)

3.7. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. General Findings

4.2. Intensity of PA

4.3. Team Sport and SA in White/Western/High Income Countries

4.4. Active School Travel

4.5. School Sport Participation

4.6. Muscle Strengthening

4.7. The Role of Sex and Gender

4.8. Ethnicity

4.9. Potential Pathological Aspects of PA

4.10. Clinical Implications

4.11. Limitations of Included Studies

4.12. Recommendations for Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Physical activity |

| SA | Suicide attempt |

| NSSI | Non-suicidal self-injury |

| YRBS | Youth Risk Behaviour Survey |

| GSHS | Global School-Based Health Survey |

| PE | Physical education |

| AST | Active school travel |

References

- World Health Organisation. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/data-research/suicide-data (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Australian Institute for Health and Welfare. Psychosocial Risk Factors and Death by Suicide. 2022. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/behaviours-risk-factors/psychosocial-risk-factors-suicide (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Gvion, Y.; Apter, A. Evidence-Based Prevention and Treatment of Suicidal Behaviour in Children and Adolescents. In The International Handbook of Suicide Prevention; O’Connor, R.C., Pirkis, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2016; pp. 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute for Health and Welfare. Deaths by Suicide Among Young People 2022. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/populations-age-groups/suicide-among-young-people (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Auger, N.; Low, N.; Chadi, N.; Israël, M.; Israël, M.; Lewin, A.; Ayoub, A.; Healy-Profitós, J.; Luu, T.M. Suicide Attempts in Children Aged 10–14 Years During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chi, G.; Taylor, A.; Chen, S.T.; Memon, A.R.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, J.; Luo, X.; Zou, L. Lifestyle Behaviors and Suicide-Related Behaviors in Adolescents: Cross-Sectional Study Using the 2019 YRBS Data. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 766972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Family Studies. Australian Legal Definitions: When Is a Child in Need of Protection? 2023. Available online: https://aifs.gov.au/resources/resource-sheets/australian-legal-definitions-when-child-need-protection (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- da Silva, A.P.C.; Henriques, M.R.; Rothes, I.A.; Zortea, T.; Santos, J.C.; Cuijpers, P. Effects of psychosocial interventions among people cared for in emergency departments after a suicide attempt: A systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, D.; Burgis, S.; Bertolote, J.M.; Kerkhof, A.J.F.M.; Bille-Brahe, U. Definitions of Suicidal Behaviour—Lessons Learned from the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study. Crisis 2006, 27, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, D.; Horrocks, J.; House, A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm: Systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 181, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickley, H.; Hunt, I.M.; Windfuhr, K.; Shaw, J.; Appleby, L.; Kapur, N. Suicide Within Two Weeks of Discharge From Psychiatric Inpatient Care: A Case-Control Study. Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of Death, Australia. 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/causes-death/causes-death-australia/latest-release (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- West, B.A.; Swahn, M.H.; McCarty, F. Children at Risk for Suicide Attempt and Attempt-related Injuries: Findings from the 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2010, 11, 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, U.; Mandal, M.K. Suicidal Behaviour: Assessment of People-at-Risk; Sage Publications India Pvt. Ltd.: New Dehli, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yohn, C.N.; Gergues, M.M.; Samuels, B.A. The role of 5-HT receptors in depression. Mol. Brain 2017, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasen, S.; Cohen, P.; Chen, H. Developmental course of impulsivity and capability from age 10 to age 25 as related to trajectory of suicide attempt in a community cohort. Suicide Life Thret. Behav. 2011, 41, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecki, G. Suicidal behaviour: Is there a genetic predisposition? Bipolar Disord. 2001, 3, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGirr, A.; Diaconu, G.; Cabot, S.B.A.; Berlim, M.T.; Turecki, G.; Pruessner, J.C.; Sablé, R. Dysregulation of the sympathetic nervous system, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and executive function in individuals at risk for suicide. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2010, 35, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, D.K. Biopsychosocial Model of Suicidal Behaviour. 2017. Available online: http://dustinkmacdonald.com/biopsychosocial-model-suicidal-behaviour (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Cooper, J.; Appleby, L.; Amos, T. Life events preceding suicide by young people. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2002, 37, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, L. Resilience as a focus of suicide research and prevention. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019, 140, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, V.J. Preventive health care for the adolescent. Am. Fam. Physician 1991, 43, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matei, D.; Luca, C.; Onu, L.; Matei, P.; Iordan, D.A.; Buculei, I. Effects of Exercise Training of the Autonomic Nervous System with a Focus on Anti-inflammatory and Antioxidants Effects. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchia, F.; Bernal, J.D.K.; Fong, D.Y. Physical Activity Interventions to Alleviate Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023, 177, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise and phyiscal fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, N.; Park, M.Y.; Kim, J.; Park, H.Y.; Hwang, H.; Lee, C.H.; Han, J.S.; So, J.; Park, J.; Lim, K. Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): A component of total daily energy expenditure. J. Exerc. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 22, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Loeffelholz, C.; Birkenfeld, A.L. Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis in Human Energy Homeostasis. South Dartmouth: Endotext [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK279077/ (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Exercise and Sports Science Australia. Exercise Inensity Guidelines. 2016. Available online: https://www.essa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Exercise-Intensity-Guildines.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Kids Health. Kids and Exercise. 2022. Available online: https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/exercise.html (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- World Health Organisation. Physical Activity. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Felez-Nobrega, M.; Haro, J.M.; Vancampfort, D.; Koyanagi, A. Sex difference in the association between physical activity and suicide attempts among adolescents from 48 countries: A global perspective. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, N.; Gupta, A.; Wong, S.; Tran, J.; Mohammad, I.Y.; Bal, S.; Fiedorowicz, J.G.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; et al. Physical Activity, suicideal ideation, suicide attempt and death among individuals with mental or other medical disorders: A systematic review of observational studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 158, 105547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, W.D.; Dopp, R.; Hudziak, J.J. Wellness Interventions in Child Psychiatry: How Exercise, Good Nutrition, and Meditation Can Help Prevention and Improve Outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 57, S47–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, N.; Gupta, A.; Fiedorowicz, J.G.; Firth, J.; Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; Schuch, F.B.; Carr, L.J.; Solmi, M. The effect of exercise on suicide ideation and behaviours: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 330, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Hallgren, M.; Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Schuch, F.B.; Mugisha, J.; Probst, M.; Van Damme, T.; Carvalho, A.F.; Stubbs, B. Physical activity and suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Nesa, F.; Das, J.; Aggad, R.; Tasnim, S.; Bairwa, M.; Ma, P.; Ramirez, G. Global Burden of mental health problems among children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: An umbrella review. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 317, 114814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boelens, M.; Smit, M.S.; Raat, H.; Bramer, W.M.; Jansen, W. Impact of organized activities on mental health in children and adolescents: An umbrella review. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 25, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.R.; Galuska, D.A.; Zhang, J.; Eaton, D.K.; Fulton, J.E.; Lowry, R.; Maynard, L.M. Psychobiology and behavioral strategies. Physical activity, sport participation, and suicidal behavior: U.S. high school students. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 2248–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.T.; Guo, T.; Yu, Q.; Stubbs, B.; Clark, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, M.; Hossain, M.M.; Yeung, A.; Griffiths, M.D.; et al. Active school travel is associated with fewer suicide attempts among adolescents from low-and middle-income countries. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021, 21, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.A.; Narayan, G. Differences in behavior, psychological factors, and environmental factors associated with participation in school sports and other activities in adolescence. J. Sch. Health 2003, 73, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; So, W.Y.; Choi, E.J. Physical activity and suicidal behaviors in gay, lesbian, and bisexual Korean adolescents. J. Men’s Health 2017, 13, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lester, D. Participation in sports activities and suicidal behaviour: A risk or a protective factor? Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 15, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oler, M.J.; Mainous, A.G., 3rd; Martin, C.A.; Richardson, E.; Haney, A.; Wilson, D.; Adams, T. Depression, suicidal ideation, and substance use among adolescents. Are athletes at less risk? Arch. Fam. Med. 1994, 3, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, R.M.; Hammermeister, J.; Scanlan, A.; Gilbert, L. Is school sports participation a protective factor against adolescent health risk behaviors? J. Health Educ. 1998, 29, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southerland, J.L.; Zheng, S.; Dula, M.; Cao, Y.; Slawson, D.L. Relationship Between Physical Activity and Suicidal Behaviors Among 65,182 Middle School Students. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taliaferro, L.A.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Johnson, K.E.; Nelson, T.F.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Sport participation during adolescence and suicide ideation and attempts. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2011, 23, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taliaferro, L.A.; Rienzo, B.A.; Donovan, K.A. Relationships between youth sport participation and selected health risk behaviors from 1999 to 2007. J. Sch. Health 2010, 80, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, J.B. Physical activity, participation in team sports, and risk of suicidal behavior in adolescents. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 12, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arat, G.; Wong, P.W.-C. The relationship between physical activity and mental health among adolescents in six middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study. Child Youth Serv. 2017, 38, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Tang, Y. The Association between Physical Education and Mental Health Indicators in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2022, 24, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.; Kim, S.A.; Seo, K. Factors Influencing Suicide Attempts of Adolescents with Suicidal Thoughts in South Korea: Using the 15th Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey (KYRBS). Iran. J. Public Health 2022, 51, 1990–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Suicidal ideation, plans and attempts: Prevalence and associated factors in school-going adolescents in Sierra Leone in 2017. J. Pscyhol. Afr. 2021, 31, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabo, D.; Miller, K.E.; Melnick, M.J.; Farrell, M.P.; Barnes, G.M. High School Athletic Participation and Adolescent Suicide: A Nationwide US Study. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2005, 40, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, F.B.; Xu, M.L.; Kim, S.D.; Sun, Y.; Su, P.Y.; Huang, K. Physical activity might not be the protective factor for health risk behaviours and psychopathological symptoms in adolescents. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2007, 43, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.G.; Cho, Y.; Yoo, S. The relations of suicidal ideation and attempts with physical activity among Korean adolescents. J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.O. Physical Activity and Suicide Attempt of South Korean Adolescents—Evidence from the Eight Korea Youth Risk Behaviors Web-based Survey. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2014, 13, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hale, G.E.; Colquhoun, L.; Lancastle, D.; Lewis, N.; Tyson, P.J. Physical activity interventions for the mental health of children: A systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2023, 49, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernert, R.; Joiner, T.E. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: A reciew of the literature. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2007, 3, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, H.S.; Park, S.; Kwon, J.A. BMI and perceived weight on suicide attempts in Korean adolescents: Findings from the Korea Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (KYRBS) 2020 to 2021. BMC Pub. Health 2023, 23, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. “Suicide” Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Knipe, D.W.; Gunnell, D.; Pearson, M.; Jayamanne, S.; Pieris, R.; Priyaadarshana, C.; Weerasinghe, M.; Hawton, K.; Konradsen, F.; Eddleston, M.; et al. Attempted suicide in Sri Lanka- An epidemiological study of household and community factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandradasa, M.; Kuruppuarachchi, K. Child and youth mental health in post war Sri Lanka. BJPsych Int. 2017, 14, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, C.R.; Howell, F.M.; Miracle, A.W. Do high school sports build character? A quasi-experiment on a natioanl sample. J. Soc. Sci. 1990, 27, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobosz, R.P.; Beaty, L.A. The relationship between athletic participation and high school students’ leadership ability. J. Adolesc. 1999, 34, 215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, J.M.; Ewing, B.T.; Waddell, G.R. The effects of high school athletic participation on education and labour market outcomes. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2000, 82, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaderbeater, B.J.; Blatt, S.J.; Quinlan, D.M. Gender-linked vulnerabilities to depressive symptoms, stress, and problem behaviours in adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 1995, 5, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R.W. The Men and the Boys; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2000; p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S.; Park, Y.S.; Allegrante, J.P.; Marks, R.; Ok, H.; Cho, K.O.; Garber, C.E. Relationship between physical activity and general mental health. Prev. Med. 2016, 55, 458–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.; Semlyen, J.; Tai, S.S.; Killaspy, H.; Osborn, D.; Popelyuk, D.; Nazareth, I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschenbeck, H.; Kohlmann, C.W.; Lohaus, A. Gender differences in coping strategies in children and adolescents. J. Individ. Differ. 2007, 28, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilsen, J. Suicide and youth: Risk factors. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandbu, A.; Bakken, A.; Sletten, M.A. Exploring the minority-majority gap in sport participation: Different patterns for boys and girls? Sport Soc. 2017, 22, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguy, G.; Sagui, E.; Fabien, Z.; Martin-Krumm, C.; Canini, F.; Trousselard, M. Anxiety and Psycho-Physiological Stress Response to Competitive Sport Exercise. Front. Psychol. 2018, 27, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Positive and Negative Effects of Various Coaching Styles on Player Performance and Development. BYU Undergrad. J. Psych. 2012, 8, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) USA: CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/index.html (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.; Chun, C.; Park, S.; Khang, Y.-H.; Oh, K. Data Resource Profile: The Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1076–1076e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance, Monitoring and Reporting; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/global-school-based-student-health-survey/methodology (accessed on 18 June 2025).

| Search Strategy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population | Children and Youth | Child * Youth Adolescen * “Young people” Teenager * Paediatric Paediatric Young person |

| Intervention | Physical activity | Exercise “Physical activity” Sport “Sedentary activity” “Sedentary behaviour” “Sedentary lifestyle” |

| Outcome | Suicide | Suicid * “Suicidal attempt” “Acute suicidality” “Chronic suicidality” “Suicide attempts” |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Children and adolescents aged 6–18 years | High level athletes |

| Intervention | Physical activity or exercise participation including individual exercise, group exercise or team sports as the independent variable |

|

| Comparison | Any comparator | |

| Outcome | Suicide attempt as the dependent variable |

|

| Other methodological considerations |

|

| Author and Year | Demographics | Dataset Used | Type of Physical Activity | Results | Quality Assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Duration per Day | Number of Days | Intensity | |||||

| Statistically Significant Results ↑ Physical Activity ↓ Suicide Attempts (n = 14) | ||||||||

| Brown, 2007 [38] | USA 14–18 years N = 10,530 | YRBS, 2003 | Team sport and participation in PA (non-specified) | Vigorous = at least 20 min of exercise that resulted in sweat and breathing hard Moderate = at least 30 min of exercise that did not result in sweat or breathing hard | Vigorous PA Frequent ≥ 6 days Regular vigorous 3–5 d Moderate PA ≥ 5 d Insufficient = moderate PA 1–4 d | Moderate or vigorous | Sports team participation lowered odds of SA in both boys and girls Engaging in vigorous PA (regular participation for girls and frequent for boys) lowered the OR of SA When participants engaged in both types of PA or felt sad/hopeless associations were not statistically significant (NSS) | 86% |

| Chen, 2021 [39] | 34 low-income countries 13–17 years N = 127,097 | GSHS, 2010–2017 | Walking or biking to school | Dependent on distance to school | Active school travel ≥5 d | Not specified (NS) | Children with active school travel had lowered OR of SA (country wide) | 100% |

| Felez-Nobrega, 2020 [31] | 48 varied income countries 12–15 years N = 136,857 | GSHS, 2009–2016 | Sports, country-specific PA | Meeting WHO PA guidelines = At least 60 min | Moderate–vigorous PA on 7 d/w | Moderate and vigorous | Meeting PA guidelines reduced OR of SA in boy and female children | 100% |

| Harrison, 2003 [40] | USA 14–15 years N = 50,168 | Minnesota Student Survey, 2001 | Team sport participation at school | NS | 1–2 h/w | NS | School team sport participation for 1–2 h/week reduced odds of SA | 64% |

| Jang, 2017 [41] | Korea 12–18 years N = 628 | Korean YRBS, 2015 | PA (non-specified) Muscle strengthening exercises | >10 min O >20 min | 1–2 days 3–4 days >5 days | Low intensity = walking Vigorous PA = breathing hard or sweating | Regular daily PA in the form of light- or vigorous-intensity exercise appears protective against suicide attempt for lesbian or bisexual girls | 100% |

| Lester, 2017 [42] | USA 13–18 years N = 138,690 | YRBS, 1991–2011 | Team sport | NS | NS | NS | Team sport participation was associated with fewer suicide attempts for both male and female children, Whites and Hispanics. | 57% |

| Li, 2021 [6] | USA 14–18 years N = 13,677 | YRBS, 2019 | Team sports (≥one team) | NS | Muscle strengthening ≥3 times/w | NS | Participation in team sport was associated with a lower risk of SA | 100% |

| Oler, 1994 [43] | USA 14–18 years N = 823 | NA | School team sport participation | NS | NS | NS | Team sport participation at school reduced SA for female children. OR for SA was higher in non-athletes compared to athletes | 100% |

| Page, 1998 [44] | USA 13–18 years N = 12,272 | YRBS, 1991 | Team sport participation at school | NS | NS | NS | Students participating in one or two team sports were significantly less likely to have attempted suicide (girl 1.3 times less likely and boys 1.47 times less likely) | 64% |

| Southerland, 2016 [45] | USA 11–14 years N = 60,715 | Tennessee Middle School YBRS, 2010 | PA (NS) Team sport School sport participation (PE) | At least 20 min | PA < 3 days/week = infrequent PA ≥3 days/week = regular | NS | Regular PA on ≥3 days/week, team sport participation and PE attendance all independently reduced odds of suicide attempt | 100% |

| Taliaferro, 2011 * [46] | USA 14–18 years N = 71,854 | YRBS, 1999–2007 | Team sport | NS | NS | NS | Participating in team sport throughout middle and high school was protective independent of confounding factors Discontinuing team sport after middle school increases OR of SA in high school | 94% |

| Taliaferro, 2010 [47] | USA 11–18 years N = 739 | NA | Team sport | NS | NS | NS | Team sport participation in boys and girls reduced OR of SA | 79% |

| Unger, 1997 [48] | USA 12–18 years N = 10,506 | YRBS, 1991 | PA (non specified exercise or sports activities) Team sport | ≥20 min of PA | 1–2 times/week 3–5 times/week 6–7 times/week | Vigorous PA | PA and team sport participation is protective against suicide attempt for male children The most protective combination is completing physical activity 3–5 times per week and playing on a team sport | 71% |

| Non Statistically Significant Results ↑ Physical Activity ↓ Suicide Attempts (n = 9) | ||||||||

| Arat, 2017 [49] | China, Phillipines, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Pakistan 11–17 years N = 23,372 | GSHS, 2003–2009 | Walk/bicycle PA (NS) | PA ≥ 60 min | 7 d/w | NS | Walking or biking to school correlated with a reduction in SA in China, Philippines, Pakistan and Thailand PA for 60 min/d correlated with a reduction in SA in children (China and Indonesia) | 86% |

| Hu, 2022 [50] | 71 varied income counties 11–18 years N = 276,169 | GSHS, NS | School sport participation | NS | 1–2 d ≥3 d | NS | Attending physical education for 1 day only or for 5 days or more each week was associated with lower odds of suicide attempt | 93% |

| Jang, 2017 [41] | Korea 12–18 years N = 628 | Korean YRBS, 2015 | PA (non-specified) Muscle strengthening exercises | >10 min OR >20 min | 1–2 d 3–4 d >5 d | Low intensity = walking Vigorous PA = breathing hard or sweating | Vigorous PA or muscle strengthening exercises for 1–4 d/w may reduce SA in gay or bisexual boys Light PA or muscle strengthening exercises for 1–4 days p/w may reduce SA in lesbian or bisexual girls | 100% |

| Kwon, 2022 [51] | Korea 12–18 years N = 7498 | Korean YRBS, 2019 | PA (NS) | >60 min | 1–3 d 4–7 d | NS | PA for 60 min/d for 1–3 d/w may reduce SA | 79% |

| Li, 2021 [6] | USA 14–18 years N = 13,677 | YRBS, 2019 | Muscle strengthening exercises | Not specified | ≥3/w | NS | Muscle strengthening exercise for ≥3 times/w may reduce SA | 100% |

| Peltzer, 2021 [52] | Sierra Leone 14–17 years N = 2798 | Sierra Leone GSHS, 2017 | PA (NS) | ≥60 min | 7 d/w | NS | Daily PA ≥60 min/d may reduce SA | 86% |

| Sabo, 2005 [53] | USA 14–18 years N = 16,262 | YRBS, 1997 | Team sport | NS | NS | Moderately involved: 1–2 teams Highly involved: ≥3 teams | Team sport participation reduced SA in male and female children Rates of injury were higher in athletes who engaged in SA and team sport compared to boys who engaged in SA and did not participate in team sport | 100% |

| Tao, 2007 [54] | China 12–18 years N = 5453 | NA | PA (NS) | Vigorous = activity making you sweat and breathe hard for ≥20 min or 7.5 metabolic equivalents (METS) Moderate = activity making you not sweat or breathe hard for ≥20 min or 4 METS | Low = PA 200–400 METS, 2–3 session of moderate or vigorous PA Moderate = PA ≥400–<560 METS, e.g., 5 session moderate PA or 3 session of vigorous PA High = PA ≥ 560, e.g., daily moderate PA or ≥4 session vigorous PA | Low-moderate and vigorous | Low-moderate and high engagement in PA may reduce SA | 100% |

| West, 2020 [13] | USA 12–18 years N = 14,041 | YRBS, 2007 | Team sport | NS | NS | NS | Team sport participation may reduce multiple SA in female children | 64% |

| Statistically Significant Results ↑ Physical Activity ↑ Suicide Attempts (n = 7) | ||||||||

| Arat, 2017 [49] | China, Phillipines, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Pakistan 11–17 years N = 23,372 | GSHS, 2003–2009 | PA (NS) Walk/bicycle | PA ≥ 60 min | 7 d/w | NS | PA for 60 min/d increased SA (Philippines) Walking/biking to school increased OR for SA (Sri Lanka) | 86% |

| Felez-Nobrega, 2020 [31] | 48 varied income countries 12–15 years N = 136,857 | GSHS, 2009–2016 | Walking to school and PA (country-specific examples) | Meeting WHO PA guidelines = ≥60 min | Moderate–vigorous PA on 7 d/w | Moderate and vigorous | Meeting PA guidelines were associated with higher OR of SA in girls | 100% |

| Hu, 2022 [50] | 71 varied income counties 11–18 years N = 276,169 | GSHS, NS | School sport participation | NS | 1–2 d ≥3 d | NS | Attending PE class for 2, 3 or 4 d/w was associated higher OR of SA in girls | 93% |

| Kwon, 2022 [51] | Korea 12–18 years N = 7498 | Korean YRBS, 2019 | PA (NS) | >60 min | 1–3 d 4–7 day | NS | PA 4–7 times/w increased OR of SA | 79% |

| Lee, 2013 [55] | Korea 12–18 years N = 74,698 | Korean YRBS, 2007 | PA (NS) | Moderate = ≥30 min PA that did not make them sweat or breathe hard Vigorous = ≥20 min PA that made them sweat or breathe hard | Moderate Insufficient 1–4 d Regular ≥5 d Vigorous Insufficient 1–2 d Regular 3–4 d Frequent ≥5 d | Moderate and vigorous PA | Male children who engaged in regular moderate PA had an increased likelihood of suicide attempt when controlling for body image Female children who performed any amount of vigorous PA were at an increased of suicide attempt compared to girls who performed no vigorous PA when controlling for body image, stress, and depression | 100% |

| Unger, 1997 [48] | USA 12–18 years N = 10,506 | YRBS, 1991 | PA alone (NS exercise or sports activities) Or in combination with team sport | ≥20 min of PA | 1–2 times/w 3–5 times/w 6–7 times/w | Vigorous PA | Female children who engaged in PA 6–7 times per week and participated in team sport had increased OR of SA | 71% |

| West, 2020 [13] | USA 12–18 years N = 14,041 | YRBS, 2007 | Team sport | NS | NS | NS | Team sport participation increased OR for SA in boys | 64% |

| Theme | Author | Statistically Significant Results (Inverse Association) ↑ Physical Activity ↓ Suicide Attempts | Non-Statistically Significant Results (Inverse Association) ↑ Physical Activity ↓ Suicide Attempts | Statistically Significant Results (Direct Association) ↑ Physical Activity ↑ Suicide Attempts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | Southerland, 2016 [45] | Regular vigorous PA for more than 20 min a day 3 or more days per week reduced odds of SA (OR: 0.93, 95% CI: 0.87–0.99). | ||

| Brown, 2007 [38] | Vigorous PA six or more days per week decreased SA for boys (OR = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.21–0.96). Vigorous-intensity PA 3–5 days per week was protective against SA for girls (OR = 0.67; 95% CI = 0.45–0.99). | |||

| Felez-Nobreg, 2020 [31] | 60 min of daily moderate–vigorous-intensity PA reduced SA for male children across 48 countries (OR = 0.78; 95% CI = 0.70–0.86). | |||

| Lee, 2013 [55] | Regular moderate (OR = 1.37; 95% CI = 1.13–1.67) and frequent vigorous-intensity (OR = 1.22 95% CI = 1.00–1.48) PA increased the risk of SA for boys after adjusting for body. Regular (OR = 1.23; 95% CI = 1.07–1.41) and frequent-vigorous-intensity (OR = 1.41; 95% CI = 1.16–1.71) exercise resulted in an increased risk of SA for girls also after adjusting for body image. Frequent vigorous-intensity remained significant for increasing odds of suicide attempt in both male (OR = 1.23; 95% CI = 1.00–1.50) and female children (OR = 1.30; 95% CI = 1.06–1.60) when further adjusting for stress and depression. | |||

| Team Sport | Taliaferro, 2011 [46] | Team sport participation during middle school and high school lowered rates of SA compared to non-participants (4.5% vs. 7.4%; p = 0.006). Discontinuing sport after middle school resulted in a 2.38 times increased risk of SA in high school (95% CI = 1.04–5.41). | ||

| Brown, 2007 [38] | Both boys (OR = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.33–0.76) and girls (OR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.53–0.82) benefited from participating in a team sport. | |||

| Lester, 2017 [42] | Participation in one or more team sports was associated with reduced SA (7.6%) compared to non-participants (9.8%) (p < 0.001). | |||

| Taliaferro, 2010 [47] | Participation in one or more team sports resulted in fewer suicide attempts for boys (OR = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.53–0.74) and girls (OR = 0.79; 95% CI = 0.07–0.09). | |||

| Southerland, 2016 [45] | Team sport participation may reduce the odds of SA independent of screen time, drug abuse and weight misperception (OR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.65–0.75). | |||

| Harrison, 2003 [40] | Team sport participation for 1–2 h or more per week decreased odds of SA (OR = 0.45; 95% CI = 0.39–0.52). | |||

| Page, 1998 [44] | Relative risk of both boy (95% CI = 1.08–2.01) and girl (95% CI = 1.06–1.59) students participating in one or two team sports corresponded to reduced odds of SA. | |||

| Sabo, 2005 [53] | Team sports appeared to be protective against SA for both girl (OR = 0.86; 95% CI = 0.65–1.14) and boy (OR = 0.83–95% CI = 0.52–1.32) children. Female children who participated in 1–2 team sports (OR = 0.92; 95% CI = 0.65–1.25) and 3 or more team sports (OR = 0.73; 95% CI = 0.52–1.02) appeared to reduce risk of SA.Male children who participated in 1–2 team sports (OR = 0.93; 95% CI = 0.54–1.58) and 3 or more teams (OR = 0.70; 95% CI = 0.45–1.08) also appeared to be protected against SA. | |||

| Tao, 2007 [54] | Low-moderate engagement in PA (OR = 0.61; 95% CI = 0.34–1.09) and high engagement in PA (OR = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.52–1.76) appeared protective against SA. | |||

| West, 2010 [13] | Team sport appeared protective against SA for female children (OR = 0.89; 95% CI = 0.70–1.14). Team sport may also be protective against injuries sustained following SA in female children (OR = 0.69; 95% CI = 0.38–1.26). | Male children participating in team sport had an increased risk of SA (OR = 1.52; 95% CI = 1.07–2.16). | ||

| Active School Travel | Chen, 2021 [39] | Walking or biking to school in 34 low-income countries decreased the odds of SA by 18% regardless of gender (OR = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.75–0.90). | ||

| Arat, 2017 [49] | Walking or biking to school appeared to reduce SA for children in China (OR = 0.75; 95% CI = 0.48–1.18), Philippines (OR = 0.98; 95% CI = 0.834–1.13), Pakistan (OR = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.68–1.12) and Thailand (OR = 0.83; 95%CI = 0.62–1.12). Exercising for 60 min daily also appeared to reduce the risk of SA in China (OR = 0.72; 95%CI = 0.46–1.12) and Indonesia (OR = 0.82; 95% CI = 0.47–1.41). | Walking or biking to school in Sri Lanka increased the rate of suicide by 1.45 times compared to children who did not engage in this type of PA (95% CI = 1.10–1.93). | ||

| School Sport | Southerland, 2016 [45] | PE attendance 2–5 times per week reduced likelihood of SA (OR:0.88; CI: 0.82–0.95). | ||

| Oler, 1994 [43] | Participation in school athletics (interschool team sport) was protective against SA for girls (p = 0.04) | |||

| Hu, 2022 [50] | Attending PE for one (OR = 0.93–95% CI = 0.84–1.04) or five days (OR = 0.89; 95% CI = 0.80–1.00) appeared to reduce risk of SA. | Attending PE class for two (OR = 1.05; 95% CI = 0.94–1.18), three (OR = 1.19; 95% CI = 1.00–1.41) or four (OR = 1.13; 95% CI = 0.93–1.38) days per week was significantly associated with an increased risk of SA. | ||

| Muscle Strengthening | Jang, 2017 [41] | For male children, muscle strengthening exercises for 1–2 days (OR = 0.541; 95% CI = 0.196–1.499) or 3–4 days (OR = 0.575; 95% CI = 0.196–1.6787) per week appeared to reduce the likelihood of SA. Similarly, muscle strengthening exercises for female children 1–2 days (OR = 0.893; 95% CI = 0.164–4.852) or 3–4 days (OR = 0.277; 95% CI = 0.044–1.756) also appeared protective against SA. | ||

| Li, 2021 [6] | Muscle strengthening for at least 3 times per week (OR = 0.74; 95% CI = 0.55–1.01) appeared to be protective against SA. | |||

| Sex and Gender | Felez-Nobreg, 2020 [31] | 60 min of moderate–vigorous-intensity PA per day reduced the odds of SA for boys (OR = 0.78; 95% CI = 0.70–0.86). | Girls who completed moderate–vigorous-intensity exercise for 60 min per day had an increased risk of SA (OR = 1.22; 95% CI = 1.10–1.35). Girls who engaged in PA 6–7 times per week and those who additionally participated in a team sport were at a 1.88- and 1.5-times increased risk of SA, respectively (PA 6–7 times per week: OR = 1.88; 1.31–2.70. PA 6–7 times per week and team sport participation: OR = 1.50; 95% CI 1.09–2.05). | |

| Unger, 1997 [48] | PA for at least 20 min, 3–7 times per week and team sport participation decreased the odds of SA in male children (PA 3–5 times per week: OR = 0.4; 95% CI = 0.23–0.72. PA 6–7 times per week: OR = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.29–0.85). The most protective combination against multiple suicide attempts was completing PA 3–5 times per week and team sport participation (OR = 0.18; 95% CI = 0.08–0.39) followed by PA 6–7 times per week and team sport participation (OR = 0.28; 95% CI = 0.15–0.54). | |||

| Jang, 2017 [41] | Lesbian or bisexual girls who engaged in light PA for 3–4 days per week had a 6.186 times higher risk of SA compared to female children who completed more than 5 days of light PA (p = 0.011). Lesbian or bisexual girls who performed no vigorous PA each week had a 7.152 increased risk of attempted suicide compared to girls who performed over 5 days of vigorous PA (95% CI = 1.273–40.164). | For gay or bisexual boys, vigorous PA 3–4 days per week may be protective against SA (OR = 0.796; 95% CI = 0.24–2.64). For lesbian or bisexual girls, light PA for 1–2 days (OR = 0.127; 95% CI = 0.008–2.041) may be protective against SA. | ||

| Ethnicity | Lester, 2017 [42] | Team sport participation reduced the odds of SA for Whites and Hispanics (p = 0.001 for both Whites and Hispanics). | ||

| Taliaferro, 2010 [47] | Sports team participation lowered the risk of SA for boys regardless of ethnicity (OR: 0.69 CI: 0.58–0.81). For girls, being White, compared other ethnicities, reduced the odds of SA (OR = 0.61 CI: 0.51–0.73). | Team sport participation increased the odds of SA for Black (p = 0.001), Hispanic (p = 0.01), and Asian girls (p = 0.01). | ||

| Potential Pathological Aspect of Physical Activty | Arat, 2017 [49] | Exercising for 60 min per day corresponded to a 1.39 times increased risk of SA in the Philippines (95% CI = 1.03–1.86). | ||

| Kwon, 2022 [51] | Exercising for 60 min a day for 1–3 days (OR = 0.968; 95% CI = 0.801–1.171) may be protective against SA. | Exercising for more than 60 min per day on four or more days per week yielded a 1.2 increase in SA (p = 0.047). | ||

| Peltzer, 2021 [52] | Exercising for 60 min daily (OR = 0.73; 95% CI = 0.51–1.06) appeared to reduce odds of SA. | |||

| Sabo, 2005 [53] | Male children who participated in 1–2 teams and attempted suicide were approximately three times more likely to result in serious injury (OR = 2.81; 95% CI = 2.81) and those involved in three or more teams were approximately five times more likely to sustain serious injury requiring medical attention (OR = 4.84; 95% CI = 1.92–12.2). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patel, M.; Branjerdporn, G.; Woerwag-Mehta, S. The Impact of Physical Activity on Suicide Attempt in Children: A Systematic Review. Children 2025, 12, 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070890

Patel M, Branjerdporn G, Woerwag-Mehta S. The Impact of Physical Activity on Suicide Attempt in Children: A Systematic Review. Children. 2025; 12(7):890. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070890

Chicago/Turabian StylePatel, Marissa, Grace Branjerdporn, and Sabine Woerwag-Mehta. 2025. "The Impact of Physical Activity on Suicide Attempt in Children: A Systematic Review" Children 12, no. 7: 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070890

APA StylePatel, M., Branjerdporn, G., & Woerwag-Mehta, S. (2025). The Impact of Physical Activity on Suicide Attempt in Children: A Systematic Review. Children, 12(7), 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070890