Quality-of-Life Outcomes Following Thyroid Surgery in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional, and Social Dimensions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

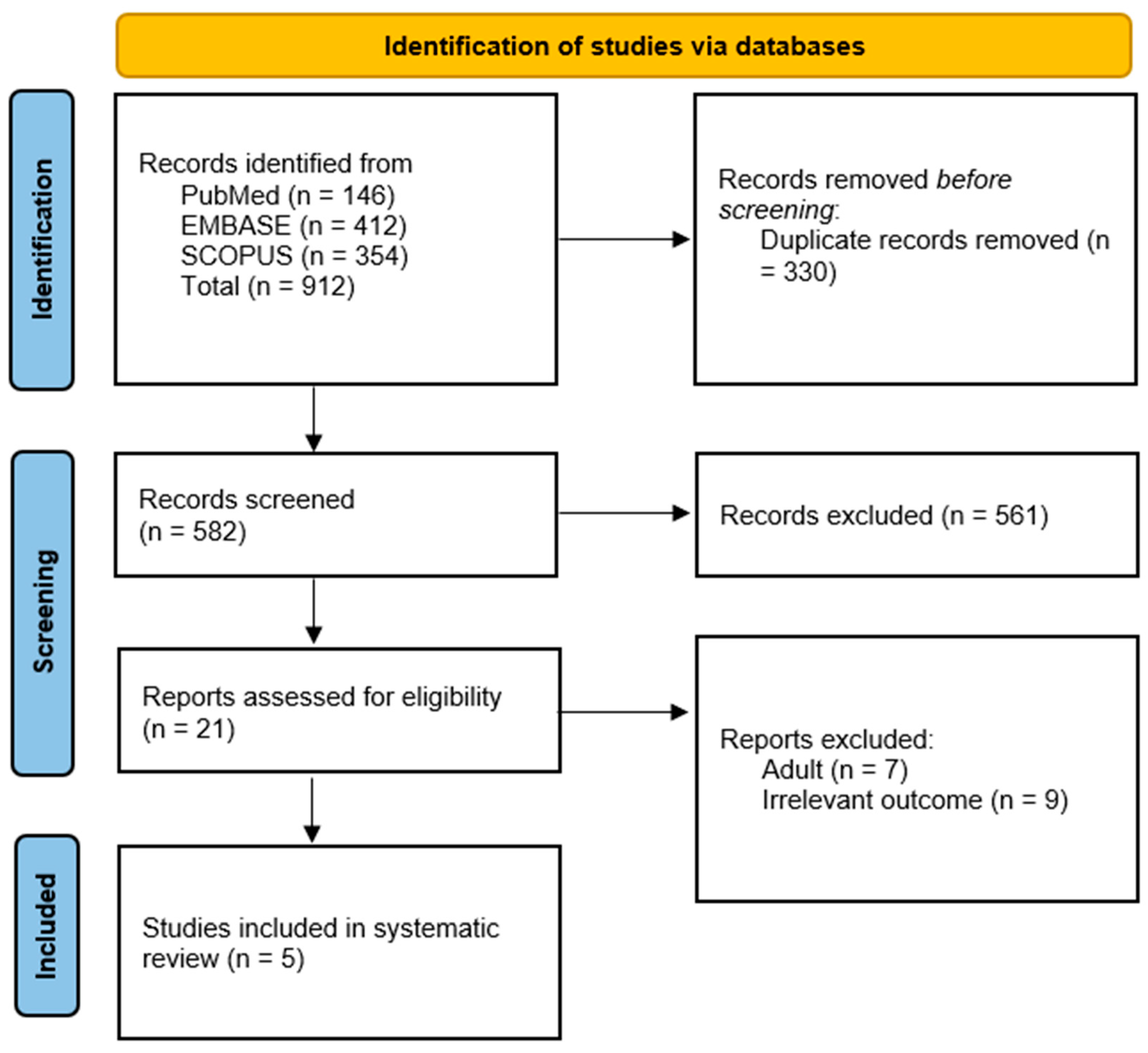

2.3. Information Sources, Search Strategy, and Study Selection

2.4. Data-Collection Process

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Summary of the Included Studies

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Qualitative Synthesis

3.3.1. Emotional Domain (e.g., Anxiety, Depression, Emotional Resilience)

3.3.2. Social Domain (e.g., Peer Interaction, Scar Stigma, School Life)

3.3.3. Physical Domain (e.g., Fatigue, Activity Limitation, Somatic Symptoms)

3.3.4. Information Needs and Support Systems

3.3.5. Surgical Approaches and Their Impact on Quality of Life

3.3.6. Factors Affecting Quality of Life

3.3.7. Age-Specific Considerations

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Our Findings

4.2. Comparing Our Results with Previous Similar Systematic Reviews

4.3. Implications of Our Findings

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| DTC | Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| PedsQL | Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 |

| THYCA-QoL | Thyroid Cancer-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| WHOQOL-100 | World Health Organization Quality of Life-100 |

| CHQ-CF87 | Child Health Questionnaire-Child Form 87 |

| SF-36 | Short Form-36 Health Survey |

| MFI-20 | Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory-20 |

| NOS | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| UT | Unilateral Thyroidectomy |

| TC | Thyroid Cancer |

| RAI | Radioactive Iodine |

| TSH | Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

Appendix A

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ((“Thyroidectomy”[Mesh] OR “Thyroid Gland/surgery”[Mesh] OR “thyroid surgery” OR “thyroidectomy” OR “total thyroidectomy” OR “partial thyroidectomy” OR “thyroid lobectomy” OR “minimally invasive thyroid surgery” OR “robot-assisted thyroidectomy” OR “endoscopic thyroid surgery” OR “thyroid resection” OR “thyroid gland removal”)) AND ((“Child”[Mesh] OR “Adolescent”[Mesh] OR “Pediatric”[Mesh] OR child* OR pediatric* OR adolescent* OR youth* OR “young patient*” OR “infant*” OR “teenager*” OR “neonate*” OR “newborn*”)) AND ((“Quality of Life”[Mesh] OR “QoL” OR “life quality” OR “health-related quality of life” OR “HRQoL” OR “psychosocial well-being” OR “psychosocial impact” OR “emotional well-being” OR “functional outcome*” OR “postoperative quality of life” OR “patient-reported outcomes” OR “PROs” OR “self-reported health status” OR “long-term outcomes” OR “health perception” OR “social functioning” OR “mental health” OR “psychological impact” OR “physical health”)) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“thyroid surgery” OR thyroidectomy OR “total thyroidectomy” OR “partial thyroidectomy” OR “thyroid lobectomy” OR “minimally invasive thyroid surgery” OR “robot-assisted thyroidectomy” OR “endoscopic thyroid surgery” OR “thyroid resection” OR “thyroid gland removal”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(child* OR pediatric* OR adolescent* OR youth* OR “young patient*” OR “infant*” OR “teenager*” OR “neonate*” OR “newborn*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“quality of life” OR “QoL” OR “life quality” OR “health-related quality of life” OR “HRQoL” OR “psychosocial well-being” OR “psychosocial impact” OR “emotional well-being” OR “functional outcome*” OR “postoperative quality of life” OR “patient-reported outcomes” OR “PROs” OR “self-reported health status” OR “long-term outcomes” OR “health perception” OR “social functioning” OR “mental health” OR “psychological impact” OR “physical health”) |

| Embase | (‘thyroid surgery’/exp OR thyroidectomy OR ‘total thyroidectomy’ OR ‘partial thyroidectomy’ OR ‘thyroid lobectomy’ OR ‘minimally invasive thyroid surgery’ OR ‘robot-assisted thyroidectomy’ OR ‘endoscopic thyroid surgery’ OR ‘thyroid resection’ OR ‘thyroid gland removal’) AND (‘child’/exp OR ‘adolescent’/exp OR pediatric* OR child* OR youth* OR “young patient*” OR “infant*” OR “teenager*” OR “neonate*” OR “newborn*”) AND (‘quality of life’/exp OR ‘QoL’ OR ‘life quality’ OR ‘health-related quality of life’ OR ‘HRQoL’ OR ‘psychosocial well-being’ OR ‘psychosocial impact’ OR ‘emotional well-being’ OR ‘functional outcome*’ OR ‘postoperative quality of life’ OR ‘patient-reported outcomes’ OR ‘PROs’ OR ‘self-reported health status’ OR ‘long-term outcomes’ OR ‘health perception’ OR ‘social functioning’ OR ‘mental health’ OR ‘psychological impact’ OR ‘physical health’) |

References

- Moleti, M.; Aversa, T.; Crisafulli, S.; Trifirò, G.; Corica, D.; Pepe, G.; Cannavò, L.; Di Mauro, M.; Paola, G.; Fontana, A.; et al. Global incidence and prevalence of differentiated thyroid cancer in childhood: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1270518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandy, J.L.; Titmuss, A.; Hameed, S.; Cho, Y.H.; Sandler, G.; Benitez-Aguirre, P. Thyroid nodules in children and adolescents: Investigation and management. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2022, 58, 2163–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, D.S.; Fallat, M.E. Thyroglossal duct and other congenital midline cervical anomalies. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2006, 15, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkees, S.A. Pediatric Graves’ disease: Management in the post-propylthiouracil Era. Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, N.; Mathonnet, M. Complications after total thyroidectomy. J. Visc. Surg. 2013, 150, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledbetter, D.J. Thyroid surgery in children. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 23, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, J.H.; Williams, G.R. Role of Thyroid Hormones in Skeletal Development and Bone Maintenance. Endocr. Rev. 2016, 37, 135–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palace, M.R. Perioperative Management of Thyroid Dysfunction. Health Serv. Insights 2017, 10, 1178632916689677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.T.; Reyes-Gastelum, D.; Kovatch, K.J.; Hamilton, A.S.; Ward, K.C.; Haymart, M.R. Energy level and fatigue after surgery for thyroid cancer: A population-based study of patient-reported outcomes. Surgery 2020, 167, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.H.; Lee, S.J.; Cho, J.G.; Choi, I.J.; Choi, Y.S.; Hong, Y.T.; Jung, S.Y.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, D.K.; et al. Care and Management of Voice Change in Thyroid Surgery: Korean Society of Laryngology, Phoniatrics and Logopedics Clinical Practice Guideline. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 15, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffler, A. Hormone replacement after thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2010, 107, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaat, A.S.; Derikx, J.P.M.; Zwaveling-Soonawala, N.; van Trotsenburg, A.S.P.; Mooij, C.F. Thyroidectomy in Pediatric Patients with Graves’ Disease: A Systematic Review of Postoperative Morbidity. Eur. Thyroid. J. 2021, 10, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaglino, F.; Bellocchia, A.B.; Tuli, G.; Munarin, J.; Matarazzo, P.; Cestino, L.; Festa, F.; Carbonaro, G.; Oleandri, S.; Manini, C.; et al. Pediatric thyroid surgery: Retrospective analysis on the first 25 pediatric thyroidectomies performed in a reference center for adult thyroid diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1126436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, F.; Wong, K.P.; Lang, B.H.; Chung, P.H.; Wong, K.K. Paediatric thyroidectomy: When and why? A 25-year institutional experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 57, 1196–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nies, M.; Klein Hesselink, M.S.; Huizinga, G.A.; Sulkers, E.; Brouwers, A.H.; Burgerhof, J.G.M.; van Dam, E.; Havekes, B.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Corssmit, E.P.M.; et al. Long-Term Quality of Life in Adult Survivors of Pediatric Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 1218–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Yao, X. Effects of different surgical approaches on health-related quality of life in pediatric and adolescent patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.A.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, Ed000142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Kurtin, P.S. PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med. Care 2001, 39, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, O.; Haak, H.R.; Mols, F.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G.A.; Nieuwlaat, W.A.; Reemst, P.H.; Huysmans, D.A.; Toorians, A.W.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V. Development of a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire (THYCA-QoL) for thyroid cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2013, 52, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canavarro, M.; Serra, A.; Simões, M.; Rijo, D.; Pereira, M.; Gameiro, S.; Quartilho, M.; Quintais, L.; Carona, C.; Paredes, T. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL). Development and psychometric properties. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 16, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hullmann, S.E.; Ryan, J.L.; Ramsey, R.R.; Chaney, J.M.; Mullins, L.L. Measures of general pediatric quality of life: Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ), DISABKIDS Chronic Generic Measure (DCGM), KINDL-R, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 4.0 Generic Core Scales, and Quality of My Life Questionnaire (QoML). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. 11), S420–S430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Laubscher, S.; Burns, R. Validation of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire among stroke patients. Stroke 1996, 27, 1812–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, E.M.; Garssen, B.; Bonke, B.; De Haes, J.C. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J. Psychosom. Res. 1995, 39, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Feldt-Rasmussen, U.; Hahn, C.H. Total Thyroidectomy Improves Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Graves’ Disease. Clin. Thyroidol. 2022, 34, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokhuijzen, E.; van der Steeg, A.F.; Nieveen van Dijkum, E.J.; van Santen, H.M.; van Trotsenburg, A.S. Quality of life and clinical outcome after thyroid surgery in children: A 13 years single center experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2015, 50, 1701–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.N.; Halada, S.; Isaza, A.; Sisko, L.; Mostoufi-Moab, S.; Bauer, A.J.; Barakat, L.P. Health-Related Quality of Life at Diagnosis for Pediatric Thyroid Cancer Patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, e169–e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biello, A.; Kinberg, E.; Menon, G.; Wirtz, E. Thyroidectomy. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls, Ed.; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Krajewska, J.; Kukulska, A.; Oczko-Wojciechowska, M.; Kotecka-Blicharz, A.; Drosik-Rutowicz, K.; Haras-Gil, M.; Jarzab, B.; Handkiewicz-Junak, D. Early Diagnosis of Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Cancer Results Rather in Overtreatment Than a Better Survival. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 571421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, V.; Siciliani, E.; Henry, M.; Payne, R.J. Health-Related Quality of Life following Total Thyroidectomy and Lobectomy for Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 4386–4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walshaw, E.G.; Smith, M.; Kim, D.; Wadsley, J.; Kanatas, A.; Rogers, S.N. Systematic review of health-related quality of life following thyroid cancer. Tumori 2022, 108, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity, Youth and Crisis; W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Keestra, S.; Högqvist Tabor, V.; Alvergne, A. Reinterpreting patterns of variation in human thyroid function: An evolutionary ecology perspective. Evol. Med. Public. Health 2021, 9, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Participants | Age at Surgery | Gender Distribution | Marital Status | Employment Status | Country | Study Design | Inclusion Criteria | Primary Outcomes Related to QoL | Follow-up | Type of Surgery | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Su et al. (2024) [16] | 84 patients | Median age: 14.27 years | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | China | Prospective observational study | Pediatric and adolescent patients with low-risk papillary thyroid carcinoma | HRQoL assessed using THYCA-QoL, PedsQL, EORTC QLQ-C30 | 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-months post-surgery | Unilateral and bilateral thyroidectomy | Bilateral thyroidectomy is associated with lower HRQoL compared to unilateral thyroidectomy. |

| Pérez et al. (2023) [29] | 92 youth with TC, 87 caregivers | 15.47 years (SD = 2.53, range 8.56–23.36) | 83.7% female | 77.2% White non-Hispanic | Baseline, 12 months, and 24 months post-surgery | USA | Cross-sectional study | Pediatric thyroid cancer patients aged 8.5–23.4 years and their caregivers | HRQoL using PedsQL and Distress Thermometer | Baseline, 12 months, and 24 months post-surgery | Surgical intervention (total thyroidectomy) | Pediatric TC patients show resilience compared to other cancers but report lower HRQoL than healthy peers; early screening is essential. |

| Rasmussen et al. (2022) [27] | 37 patient–parent pairs | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Denmark | Cross-sectional study | Patients aged 12–19 undergoing total thyroidectomy for Graves’ disease, along with their parents, completed surveys before and at least six months post-surgery. | Disease-specific QoL | Not specified | Surgical intervention (total thyroidectomy) | In high-volume surgical settings with low complication rates, total thyroidectomy for pediatric Graves’ disease improves disease-specific QoL and psychosocial functioning with minimal scar-related concerns. |

| Nies et al. (2016) [15] | 67 survivors, 56 controls | Not specified | 86.6% female (survivors) | 64.2% in a relationship | 91.0% employed/full-time students | Netherlands | Cross-sectional study | Adult survivors of pediatric DTC diagnosed <18 years, follow-up ≥5 years | Generic HRQoL, fatigue, anxiety, depression, thyroid cancer-specific HRQoL | Median 17.8 years (range 5.0–44.7) | Total thyroidectomy and 131-I administration | Overall normal QoL in survivors, with mild impairments in some domains. |

| Stokhuijzen et al. (2015) [28] | 40 patients | Mean age: 13.7 years | 72.5% female | Not specified | Not specified | Netherlands | Retrospective cohort study | Patients who underwent thyroid surgery before age 19 years (2000–2012) | QoL assessed using CHQ-CF87 and WHOQOL-100 | Not specified | Total thyroidectomy and hemithyroidectomy | QoL significantly affected by surgery; improved with age; hemithyroidectomy has fewer negative effects. |

| ID | Study Design | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total Score/9 | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Su et al. (2024) [16] | Cohort | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | High quality |

| Pérez et al. (2023) [29] | Cross-sectional | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Moderate quality |

| Rasmussen et al. (2022) [27] | Cross-sectional | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | Moderate quality |

| Nies et al. (2016) [15] | Cross-sectional | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 | High quality |

| Stokhuijzen et al. (2015) [28] | Cohort | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 | Moderate quality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alansari, A.N.; Zaazouee, M.S.; Najar, S.; Elshanbary, A.A. Quality-of-Life Outcomes Following Thyroid Surgery in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional, and Social Dimensions. Children 2025, 12, 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070891

Alansari AN, Zaazouee MS, Najar S, Elshanbary AA. Quality-of-Life Outcomes Following Thyroid Surgery in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional, and Social Dimensions. Children. 2025; 12(7):891. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070891

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlansari, Amani N., Mohamed Sayed Zaazouee, Safaa Najar, and Alaa Ahmed Elshanbary. 2025. "Quality-of-Life Outcomes Following Thyroid Surgery in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional, and Social Dimensions" Children 12, no. 7: 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070891

APA StyleAlansari, A. N., Zaazouee, M. S., Najar, S., & Elshanbary, A. A. (2025). Quality-of-Life Outcomes Following Thyroid Surgery in Pediatric Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional, and Social Dimensions. Children, 12(7), 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070891