The Impact of Social Media Disorder, Family Functioning, and Community Social Disorder on Adolescents’ Psychological Distress: The Mediating Role of Intolerance to Uncertainty

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

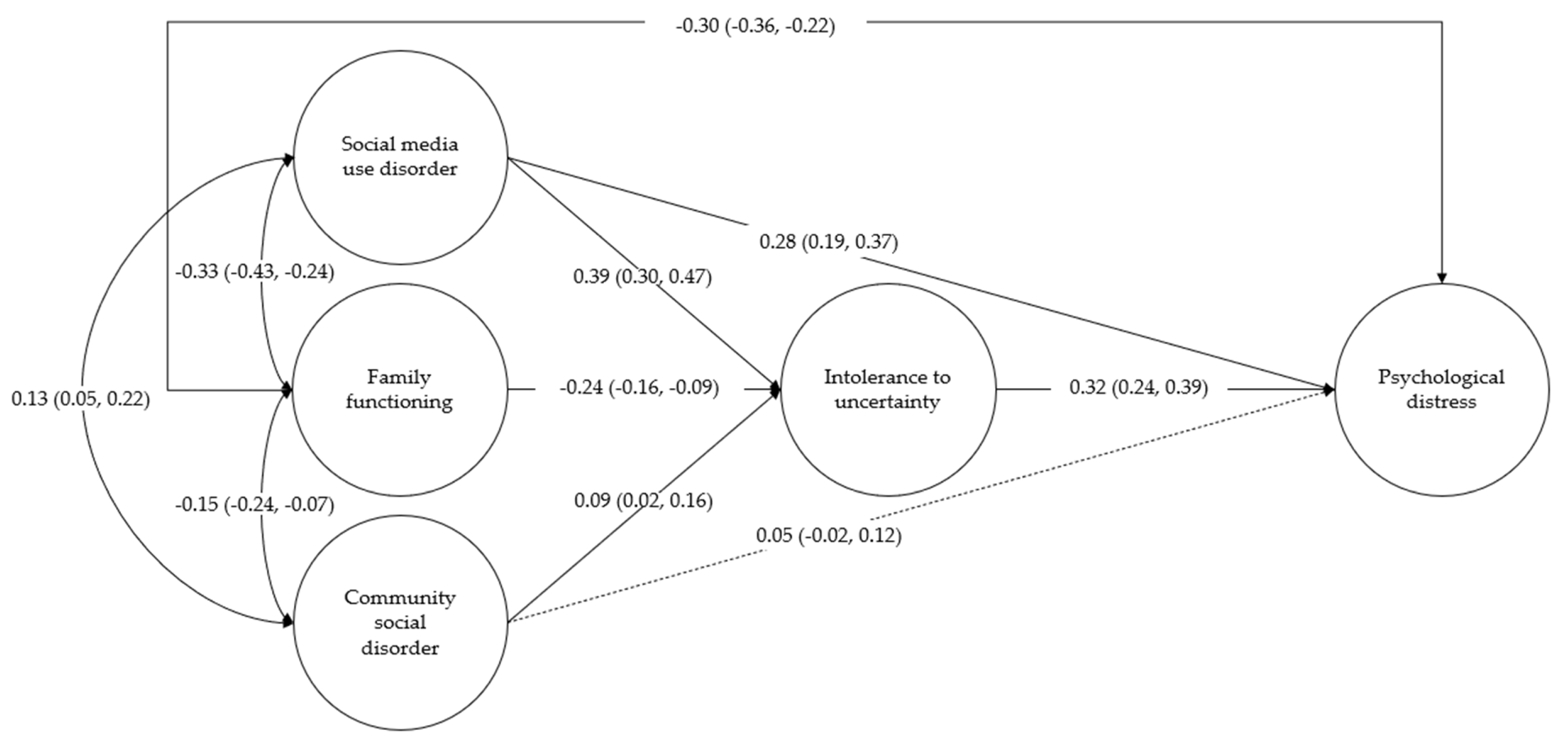

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pfeifer, J.H.; Allen, N.B. Puberty Initiates Cascading Relationships Between Neurodevelopmental, Social, and Internalizing Processes Across Adolescence. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 89, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, J.V.; Sanabria-Mazo, J.P.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Forero, C.G. The pros and cons of bifactor models for testing dimensionality and psychopathological models: A commentary on the manuscript “A systematic review and meta-analytic factor analysis of the depression anxiety stress scales”. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 27, e12386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.Y.; Yuliawati, L.; Cheung, S.H. A systematic review and meta-analytic factor analysis of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 27, e12362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modecki, K.; Zimmer-Gembeck, M.; Guerra, N. Emotion Regulation, Coping, and Decision Making: Three Linked Skills for Preventing Externalizing Problems in Adolescence. Child. Dev. 2017, 88, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, K.; Platt, J. Annual Research Review: Sex, gender, and internalizing conditions among adolescents in the 21st century—Trends, causes, consequences. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2024, 65, 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention CDCHomepage [Internet]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/index.html (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- García-Mendoza, M.D.C.; Parra-Jiménez, Á.; Freijo, E.B.A.; Arnett, J.; Sánchez-Queija, I. Family relationships and family predictors of psychological distress in emerging adult college students: A 3-year study. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2023, 48, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.G.; Quan-Haase, A. The social-ecological model of cyberbullying: Digital media as a predominant ecology in the everyday lives of youth. New Media Soc. 2022, 26, 5507–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.N.; Rudaizky, D.; Mahalingham, T.; Clarke, P.J.F. Investigating the links between objective social media use, attentional control, and psychological distress. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 361, 117400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, T.Z. Multiple Regression and Beyond: An Introduction to Multiple Regression and Structural Equation Modeling; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety, and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnidge, M.; Peacock, C.; Kim, B.; Kim, Y.; Xenos, M.A. Networks and Selective Avoidance: How Social Media Networks Influence Unfriending and Other Avoidance Behaviors. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2022, 41, 1017–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Lemmens, J.S. Valkenburg PM. The Social Media Disorder Scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, M.; Stevens, G.W.M.; Finkenauer, C.; Koning, I.M.; van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M. Validation of the Social Media Disorder Scale in Adolescents: Findings from a Large-Scale Nationally Representative Sample. Assessment 2021, 29, 1658–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, I.; Lepri, B.; Neoh, M.J.Y.; Esposito, G. Social media usage and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 508595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, C.; Gini, G.; Vieno, A.; Spada, M.M. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Meier, A.; Beyens, I. Social media use and its impact on adolescent mental health: An umbrella review of the evidence. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Eijnden, R.J.J.M.; Koning, I.; Doornwaard, S.; van Gurp, F.; Ter Bogt, T. The impact of heavy and disordered use of games and social media on adolescents’ psychological, social, and school functioning. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilkstein, G. The Family APGAR: A proposal for family function test and its use by physicians. J. Fam. Pract. 1978, 6, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, P.; Xu, F.; Gu, M.; Chen, J. Longitudinal associations between family conflict, intergenerational transmission, and adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Evidence from China Family Panel studies (2016–2020). Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2025, 19, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ma, Z.; Fan, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Fan, F. Associations Between Family Function and Non-suicidal Self-injury Among Chinese Urban Adolescents with and Without Parental Migration. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2025, 56, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeber, L.; Hops, H.; Davis, B. Family Processes in Adolescent Depression. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 4, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Hu, N.; Yao, Z.; Peng, B. Family functioning and adolescent depression: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and peer relationships. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 962147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santvoort, F.; Hosman, C.; Janssens, J.; Doesum, K.; Reupert, A.; Loon, L. The Impact of Various Parental Mental Disorders on Children’s Diagnoses: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 18, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetti, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; Seeman, T.E. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 330–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsbury, M.; Clayborne, Z.; Colman, I.; Kirkbride, J. The protective effect of neighbourhood social cohesion on adolescent mental health following stressful life events. Psychol. Med. 2019, 50, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, D.; Farrell, C.; Welsh, B.C. Broken (windows) theory: A meta-analysis of the evidence for the pathways from neighborhood disorder to resident health outcomes and behaviors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 228, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarros-Basterretxea, J.; Overall, N.; Herrero, J.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J. Considering the Effect of Sexism on Psychological Intimate Partner Violence: A Study with Imprisoned Men. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2019, 11, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriol, X.; Miranda, R.; Amutio, A.; Acosta, H.C.; Mendoza, M.C.; Torres-Vallejos, J. Violent relationships at the social-ecological level: A multi-mediation model to predict adolescent victimization by peers, bullying, and depression in early and late adolescence. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, T.; Brooks-Gunn, J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 309–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelmark, M.; Aarø, L.; Henriksen, S.; Siqveland, J.; Torsheim, T. Chronic Social Stress in the Community and Associations with Psychological Distress: A Social Psychological Perspective. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2004, 6, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G. Why we should focus more attention on uncertainty distress and intolerance of uncertainty in adolescents and emerging adults. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 2871–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N. Fear of the unknown: One fear to rule them all? J. Anxiety Disord. 2016, 41, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlenton, R.N. Into the unknown: A review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016, 39, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerde, J.; Hemphill, S.A. Examination of associations between informal help-seeking behavior, social support, and adolescent psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. Dev. Rev. 2018, 47, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmanağaoğlu, N.; Creswell, C.; Dodd, H.F. Intolerance of Uncertainty, anxiety, and worry in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, L.; Becker, B.; Dou, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Mei, Y.; Li, H.; Lei, Y. Intolerance of uncertainty enhances adolescent fear generalization in both perceptual-based and category-based tasks: fNIRS studies. Behav. Res. Ther. 2024, 183, 104650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bados, A.; Solanas, A.; Andrés, R. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS). Psicothema 2005, 17, 679–683. [Google Scholar]

- Bottesi, G.; Noventa, S.; Freeston, M.H.; Ghisi, M. Seeking certainty about Intolerance of Uncertainty: Addressing old and new issues through the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-Revised. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G.; Iannattone, S.; Carraro, E.; Lauriola, M. The assessment of Intolerance of Uncertainty in youth: An examination of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-Revised in Italian nonclinical boys and girls. Res. Child. Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2023, 51, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, E.; Herrero, J. Perceived neighborhood social disorder and attitudes towards reporting domestic violence against women. J. Interpers. Violence 2006, 22, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998–2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, A.; Gmelin, T.; Stein, B.; Miller, E. Depressed adolescents’ positive and negative use of social media. J. Adolesc. 2017, 55, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Ren, L.; Li, K.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Rotaru, K.; Wei, X.; Yücel, M.; Albertella, L. Understanding the Association Between Intolerance of Uncertainty and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Network Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 917833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, G.; Lyu, H. Future Expectations and Internet Addiction Among Adolescents: The Roles of Intolerance of Uncertainty and Perceived Social Support. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 727106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, R.; Wei, M.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J. The mediation and interaction effects of Internet addiction in the association between family functioning and depressive symptoms among adolescents: A four-way decomposition. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 356, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossen, H.G.; van den Eijnden, R.J.; Visser, I.; Koning, I.M. Parenting and Problematic Social Media Use: A Systematic Review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2024, 11, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottesi, G.; Gürdere, C.; Cerea, S.; Ghisi, M.; Sica, C. Familial Patterns of Intolerance of Uncertainty: Preliminary Evidence in Female University Students. J. Cogn. Ther. 2020, 13, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Psychological distress | - | |||||

| 2. Intolerance of uncertainty | 0.54 *** | - | ||||

| 3. Social media use disorder | 0.53 *** | 0.45 *** | - | |||

| 4. Family functioning | −0.49 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.33 *** | - | ||

| 5. Community social disorder | 0.18 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.13 ** | −0.15 *** | - | |

| M | 9.4 | 33.2 | 9.1 | 12.4 | 2.2 | |

| SD | 8.8 | 8.3 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 1.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morillo-Sarto, H.; Torres-Vallejos, J.; Usán, P.; Barrada, J.R.; Juarros-Basterretxea, J. The Impact of Social Media Disorder, Family Functioning, and Community Social Disorder on Adolescents’ Psychological Distress: The Mediating Role of Intolerance to Uncertainty. Children 2025, 12, 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070861

Morillo-Sarto H, Torres-Vallejos J, Usán P, Barrada JR, Juarros-Basterretxea J. The Impact of Social Media Disorder, Family Functioning, and Community Social Disorder on Adolescents’ Psychological Distress: The Mediating Role of Intolerance to Uncertainty. Children. 2025; 12(7):861. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070861

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorillo-Sarto, Héctor, Javier Torres-Vallejos, Pablo Usán, Juan Ramón Barrada, and Joel Juarros-Basterretxea. 2025. "The Impact of Social Media Disorder, Family Functioning, and Community Social Disorder on Adolescents’ Psychological Distress: The Mediating Role of Intolerance to Uncertainty" Children 12, no. 7: 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070861

APA StyleMorillo-Sarto, H., Torres-Vallejos, J., Usán, P., Barrada, J. R., & Juarros-Basterretxea, J. (2025). The Impact of Social Media Disorder, Family Functioning, and Community Social Disorder on Adolescents’ Psychological Distress: The Mediating Role of Intolerance to Uncertainty. Children, 12(7), 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070861