Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents: An Integrative Review Based on the Behavior Change Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Main Discussion

2.1. Developmental Characteristics of Adolescence

2.2. Key Components of Mental Health Interventions

2.3. Types and Strategies of Adolescent Mental Health Interventions by Stage

2.4. Types of Adolescent Mental Health Interventions by Setting

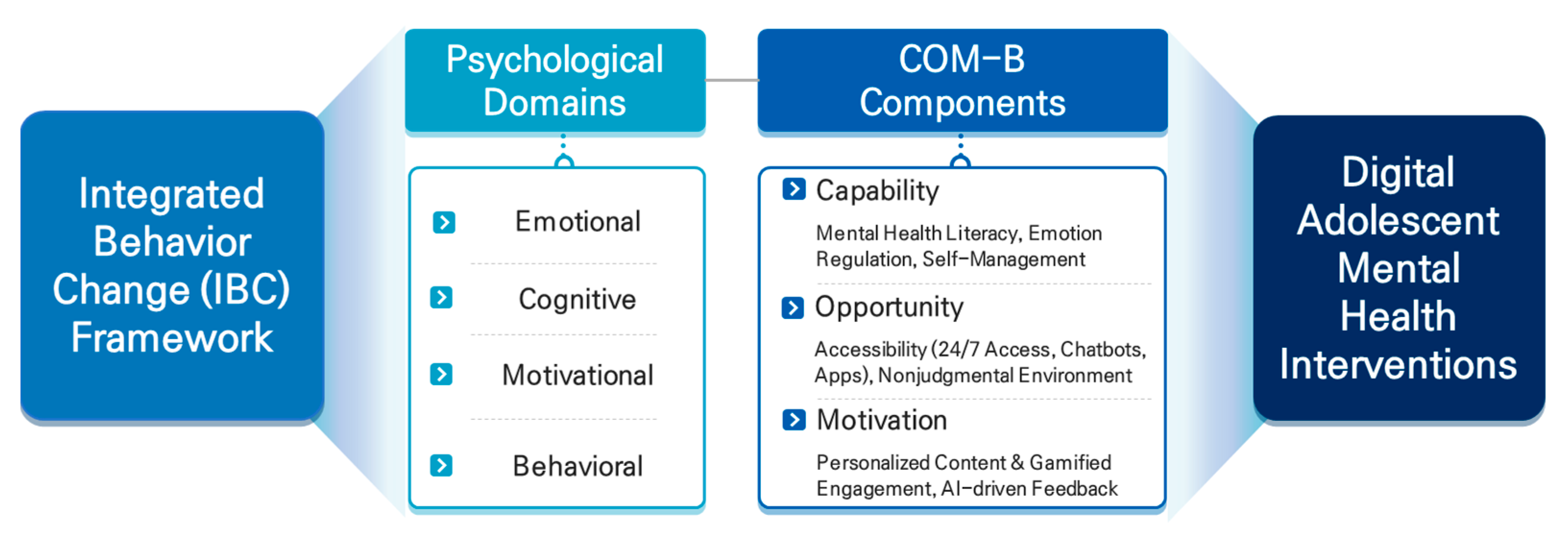

2.5. Current Landscape of Digital Adolescent Mental Health Services and Analysis from a Behavioral Change Perspective

3. Study Limitations and Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DHI | Digital health intervention |

| CBT | Cognitive behavior therapy |

| cCBT | Computerized cognitive behavior therapy |

| DTx | Digital therapeutics |

References

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Mental Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst, F.C.; Achenbach, T.M.; Van Der Ende, J.; Erol, N.; Lambert, M.C.; Leung, P.W.L.; Silva, M.A.; Zilber, N.; Zubrick, S.R. Comparisons of problems reported by youths from seven countries. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Flisher, A.J.; Hetrick, S.; McGorry, P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007, 369, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, E.J.; Foley, D.L.; Angold, A. 10-year research update review: The epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: II. Developmental epidemiology. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrazek, P.J.; Haggerty, R.J. Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, C.; Morriss, R.; Martin, J.; Amani, S.; Cotton, R.; Denis, M.; Lewis, S. Technological innovations in mental healthcare: Harnessing the digital revolution. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 206, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.R.; Fuchs, E.; Horvath, K.J.; Scal, P. Distressed and looking for help: Internet intervention support for arthritis self-management. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, C.; Martin, J.; Amani, S.; Cotton, R.; Denis, M.; Lewis, S. Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems: A systematic and scoping review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 715–736. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach, G. What is e-health? J. Med. Internet Res. 2001, 3, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, T.; Bavin, L.; Stasiak, K.; Hermansson-Webb, E.; Merry, S.N.; Cheek, C.; Lucassen, M.; Lau, H.M.; Pollmuller, B.; Hetrick, S. Serious games for the treatment or prevention of depression: A systematic review. Rev. Psicopatol. Psicol. Clin. 2014, 19, 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen, M.F.; Merry, S.N.; Hatcher, S.; Frampton, C.M. Rainbow SPARX: A novel approach to addressing depression in sexual minority youth. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2015, 22, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, T.; Lucassen, M.; Stasiak, K.; Sutcliffe, K.; Merry, S. Technology matters: SPARX–computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescent depression in a game format. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2021, 26, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, N.; Lobban, F.; Emsley, R.; Bucci, S. Acceptability of interventions delivered online and through mobile phones for people who experience severe mental health problems: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, P.J.; Calear, A.L. Preferences for internet-based mental health interventions in an adult online sample: Findings from an online community survey. JMIR Ment. Health 2017, 4, e7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Mills, K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.J.; Getz, S.; Galvan, A. The adolescent brain. Dev. Rev. 2008, 28, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Hum. Dev. 1972, 15, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkind, D. Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Dev. 1967, 38, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, B.; Collins, W.A. Parent–child relationships during adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 3rd ed.; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B.B.; Larson, J. Peer relationships in adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 3rd ed.; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 74–103. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.M.; Kuosmanen, T.; Barry, M.M. A systematic review of online youth mental health promotion and prevention interventions. J. Youth Adolesc. 2015, 44, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, L.; Gunnell, D.; Sharp, D.; Donovan, J.L. Factors influencing help seeking in mentally distressed young adults: A cross-sectional survey. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2007, 57, 807–813. [Google Scholar]

- Torous, J.; Myrick, K.J.; Rauseo-Ricupero, N.; Firth, J. Digital mental health and COVID-19: Using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e18848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, M.E.; Nicholas, J.; Christensen, H. A systematic assessment of smartphone tools for suicide prevention. PLoS ONE 2019, 11, e0152285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santre, S. Mental health promotion in adolescents. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 18, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Farías, J.C.; Mindel, C.; D’Amico, F.; Evans-Lacko, S. Pilot evaluation to assess the effectiveness of youth peer community support via the Kooth online mental wellbeing website. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 2007, 6, 168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Yoon, J.; Cho, Y.; Chun, J. Systematic review of extended reality digital therapy for enhancing mental health among South Korean adolescents and young adults. Korean J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 34, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M. Personal Recovery and Mental Illness: A Guide for Mental Health Professionals; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weare, K.; Nind, M. Mental health promotion and problem prevention in schools: What does the evidence say? Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, 29–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, K.H.; Zetterqvist, M. An emotion regulation skills training for adolescents and parents: Perceptions and acceptability of methodological aspects. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1448529. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, R.; Patalay, P.; Humphrey, N. A systematic literature review of existing conceptualisation and assessment measures of mental health literacy in adolescent research: Current challenges and inconsistencies. Int. J. Environ. Res. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 607. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Torous, J.; Wisniewski, H.; Liu, G.; Keshavan, M. Mental health mobile phone app usage, concerns, and benefits among psychiatric outpatients: Comparative survey study. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e11715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickwood, D.; Deane, F.P.; Wilson, C.J.; Ciarrochi, J. Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Adv. Ment. Health 2007, 4, 218–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea National Center for Mental Health. National Mental Health Survey of Korea–Child & Adolescent 2022; Korea National Center for Mental Health: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10107010000&bid=0046&act=view&list_no=1482939&tag=&cg_code=&list_depth=1 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Kooth. Kooth Annual Impact Report. Available online: https://connect.kooth.com (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Sawyer-Morris, G.; Wilde, J.A.; Molfenter, T.; Taxma, F. Use of digital health and digital therapeutics to treat SUD in criminal justice settings: A review. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2023, 27, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanata, T.; Takeda, K.; Fujii, T.; Iwata, R.; Hiyoshi, F.; Iijima, Y.; Nakao, T.; Murayama, K.; Watanabe, K.; Kikuchi, T.; et al. Gender differences and mental distress during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Japan. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.K.; Darcy, A.; Vierhile, M. Delivering cognitive behavior therapy to young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety using a fully automated conversational agent (Woebot): A randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2017, 4, e7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

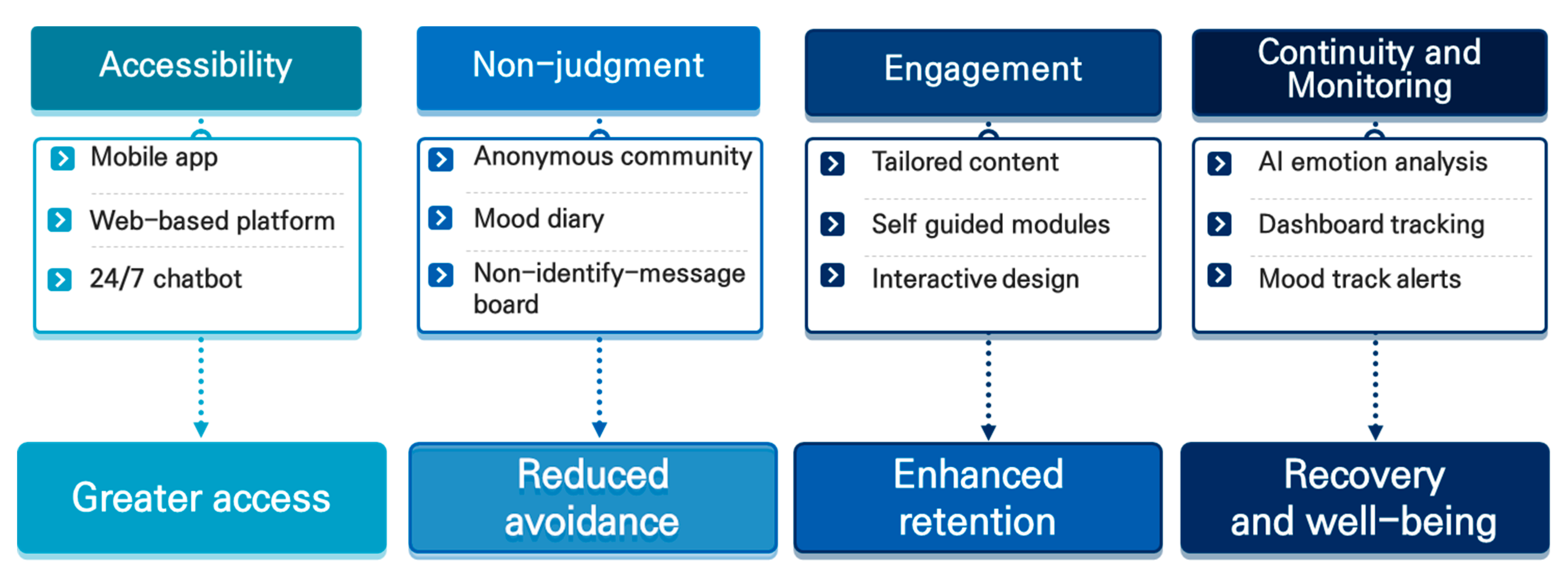

| Component | Description | Example of Digital Application |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | Providing access to interventions regardless of time and location | Mobile apps, web-based counseling, 24/7 chatbot services |

| Nonjudgmental environment | Offering a safe space where users can express emotions without fear of stigma or evaluation | Anonymous online communities, emotion diary applications |

| Person-centered engagement | Designing interventions that emphasize autonomy and self-direction for adolescents | Personalized content recommendations, self-guided therapy modules |

| Continuity and monitoring | Enabling long-term tracking of emotional states and timely responses to changes | AI-based emotion analysis, automated alerts, risk detection system |

| Type (Stage) | Objective | Strategic Approach | Applied Technology | Representative Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preventive (Pre-onset) | Minimizing risk factors and enhancing protective factors | - Mental health literacy education - Emotion regulation training - Stress management strategies | - Mobile applications - Self-assessment tools - CBT-based digital content | Kooth (UK), MindMatters (Australia) |

| Early | Prevention of symptom worsening, early detection, and timely intervention | - Risk group screening - Emotion monitoring - Tailored counseling connection | - AI-based emotion analysis - App-based screening tools - Digital CBT | Maeum-Kkumteo (Republic of Korea), FOCUS (Finland) |

| Recovery & Empowerment-focused | Functional recovery, autonomy enhancement, and social reintegration | - Self-management training - Peer support - Restoration of self-esteem | - DTx platforms - Emotion diary - Online counseling/communities | reSET-A (USA) MARO (Republic of Korea) |

| School | Community | Digital | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | In-school education and counseling systems | Public health centers, mental health centers, local welfare institutions | Smartphone applications, web-based platforms |

| Strategies | Mental health literacy education, emotion regulation training, screening | Family counseling, crisis intervention, community-based networking | Self-assessment tools, chatbots, AI-based emotion analysis, CBT apps, digital therapeutics (DTx) |

| Target | General student population, high-risk youth within the school system | Vulnerable youth, out-of-school adolescents, families included | All adolescents with access to digital devices |

| Strengths | High accessibility, early identification through educators | Ecological approach, family engagement, multidisciplinary intervention possible | No time or location constraints, anonymity, high autonomy |

| Limitations | Risk of stigma, limited mental health expertise among teachers | Regional disparities in resources, low voluntary engagement | Privacy concerns, difficulty sustaining engagement |

| Examples | School-based mental health education programs, school counseling rooms | Youth counseling centers, regional mental health and welfare programs | Kooth (UK), Maeum-Kkumteo (Republic of Korea), reSET-A (USA) |

| Service | Country | Psychological Domains (IBC) | COM-B Components | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kooth | UK | Emotional (self-awareness via journaling), Cognitive (psychoeducation), Motivational (peer support) | Capability (self-guided modules), Opportunity (24/7 access, anonymity), Motivation (peer engagement) | Pilot evaluation (Stevens et al., 2022 [30]) |

| Maeum-Kkumteo | Korea | Emotional (emotion diary), Cognitive (self-assessment feedback), Motivational (automated coaching) | Capability (self-assessment), Opportunity (mobile platform access), Motivation (personalized reminders) | Early service reports, no published RCT |

| MARO | Korea | Emotional (emotion tracking), Cognitive (self-expression via emotion diary), Motivational (empathy-based community) | Capability (emotion monitoring), Opportunity (anonymous community), Motivation (personalized coaching) | Internal reports, no published RCT |

| reSET-A | USA | Cognitive (CBT modules), Behavioral (relapse prevention training), Motivational (adherence feedback) | Capability (skills training), Opportunity (app-based monitoring), Motivation (personalized feedback) | Approved DTx, clinical trials available |

| IBC Component | Intervention Focus | Digital Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Capability | Mental health literacy, emotion regulation training, self-management skills | Online psychoeducation, CBT-based mobile apps, emotion diary tools |

| Opportunity | Accessibility, anonymity, nonjudgmental environments | 24/7 chatbot services, mobile apps, anonymous peer communities |

| Motivation | Personalized content, self-directed engagement, gamification | AI-based emotion analysis, personalized feedback, gamified CBT modules |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, S.H.; Chun, T.K.; Nam, Y.J.; Kim, T.W.; Cho, Y.H.; Son, S.J.; Roh, H.W.; Hong, C.H. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents: An Integrative Review Based on the Behavior Change Approach. Children 2025, 12, 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060770

Hong SH, Chun TK, Nam YJ, Kim TW, Cho YH, Son SJ, Roh HW, Hong CH. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents: An Integrative Review Based on the Behavior Change Approach. Children. 2025; 12(6):770. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060770

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Sun Hwa, Tae Kyung Chun, You Jin Nam, Tae Wi Kim, Yong Hyuk Cho, Sang Joon Son, Hyun Woong Roh, and Chang Hyung Hong. 2025. "Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents: An Integrative Review Based on the Behavior Change Approach" Children 12, no. 6: 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060770

APA StyleHong, S. H., Chun, T. K., Nam, Y. J., Kim, T. W., Cho, Y. H., Son, S. J., Roh, H. W., & Hong, C. H. (2025). Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents: An Integrative Review Based on the Behavior Change Approach. Children, 12(6), 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12060770